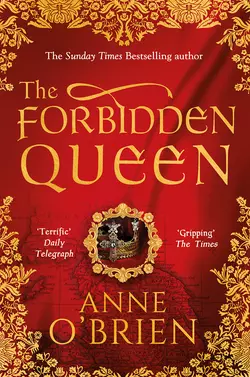

The Forbidden Queen

Anne OBrien

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 471.37 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The Forbidden Queen, электронная книга автора Anne OBrien на английском языке, в жанре современная зарубежная литература