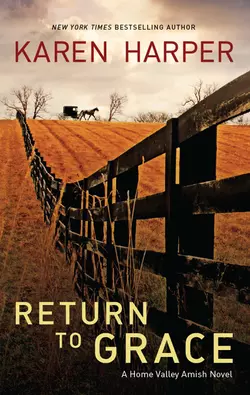

Return to Grace

Karen Harper

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 463.26 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: In the shadows of a graveyard, a shot rings out…Hannah Esh fled the Home Valley Amish community with a broken heart, throwing herself into her worldly dreams of a singing career instead. But as much as she tries to run from her past, something keeps pulling her back. On a whim, she brings four worldly friends to the Amish graveyard near her family’s home for a midnight party on Halloween.But when shots are fired and one of her friends is killed, Hannah is pulled back into the world of her past. The investigation into the shooting uncovers deep-buried secrets that shock the peaceful Amish village to its core. Determined to prove her value to the community she left behind, Hannah attempts to bridge two cultures, working closely with both handsome, arrogant FBI agent Linc Armstrong and her former betrothed, Seth Lantz, who is now widowed with a young daughter.Caught between Seth and Linc, between old and new, Amish and worldly, Hannah must chose her future. Unless a killer, bent on secrecy, chooses it for her."Harper, a master of suspense, keeps readers guessing about crime and love until the very end." –Booklist starred review on Fall From Pride“Danger and romance find their way into Ohio Amish country…lively and endearing.”—Publishers Weekly on Fall From Pride