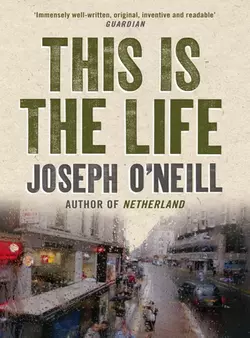

This is the Life

Joseph O’Neill

The debut novel from Joseph O'Neill, author of the Man Booker Prize longlisted and Richard & Judy pick, ‘Netherland’.James Jones is slipping steadily through life. He has a steady job as a junior partner at a solicitor's firm, a steady girlfriend and a steady mortgage. Nothing much is happening in Jones's life but he really doesn't mind – this is exactly the way he likes it.Michael Donovan, meanwhile, is a star – a world-class international lawyer and advocate – he's everything Jones wanted to be and isn't. Jones was once Donovan's pupil and, for a while, it looked like he too would make his name – but he left that high-powered world behind a long time ago, or so he thought.One day Jones reads in the paper that Donovan has collapsed in court – then, out of the blue, Donovan contacts him; he has a job he needs Jones to work on…Joseph O'Neill's debut is wonderfully clever and comic novel – about ambitions and aspirations and the realities that they inevitably collide with.

JOSEPH O’NEILL

This is the Life

DEDICATION (#ulink_ccf9de2e-3d38-501f-96c9-efa2e18e5566)

To my mother and to my father,

and to their mothers

CONTENTS

COVER (#ua325cba5-6859-5f1d-b5ad-389a75938678)

TITLE PAGE (#u0a1247df-1fb9-5c06-a020-09039c1ed4cb)

DEDICATION (#ucb36d363-c071-5d8b-820e-b45706161f57)

ONE (#ueff47412-edf5-559f-89d6-f3e880391bb5)

TWO (#ue3bf6f9b-7a7c-59a1-a772-f7826f728861)

THREE (#u09124d9d-3e1f-5584-b81c-33df1773b6d5)

FOUR (#u5648d1be-e529-5788-99ed-12f07eb55005)

FIVE (#u9c0b6fca-981e-55bc-ada1-8b7d9ec87984)

SIX (#u60ea9865-3138-5e3e-bd7f-2d42ec42f759)

SEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

EIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

NINE (#litres_trial_promo)

TEN (#litres_trial_promo)

ELEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

TWELVE (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

FOURTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

FIFTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

SIXTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

SEVENTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

EIGHTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

NINETEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (#litres_trial_promo)

BY THE SAME AUTHOR (#litres_trial_promo)

COPYRIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER (#litres_trial_promo)

ONE (#ulink_4dcc8cc8-8a70-5fee-8398-580bdf3db33f)

The other day I was queueing up at the bank. The man in front of me, a man in black leather trousers and jacket, had long fair hair which was tied together below the shoulders with ribbon. The hair looked as though it had not been washed for several years, and its strands were so intertwined, so caked with adhesive, that it had solidified. It was impossible to tell which hair was which, or where it came from or led to. The filaments started pretty distinctly, each springing cleanly from the scalp; but once they reached ear level, where they melled, they became indistinguishable from each other and lost in a blur. I stepped back slightly in the queue. It was not a mane that I wanted to get too close to.

I mention the incident because the events I am about to relate are ravelled in my mind like those hairs. Their meanings are twisted and tied together in unfamiliar knots that will not easily undo – at the moment, at the start of this undertaking, I feel like a blindfolded man fingering at running bowlines, marling hitches, sheepshanks and cuckold’s necks. This is partly due to my own entanglement in what I am preparing to describe, and the cock-eyed viewpoint that results from such a snarled involvement. Spectators, after all, see more of a play than its players.

What I am aiming to do is run a comb through the matted locks of my memory, run through the facts one more time as I remember them in the hope that, in doing so, as the threads separate and disentangle, a pattern of sorts will emerge. When I say pattern, I do not mean a swirling motif of significations: I mean a straightforward, ordinary picture of what happened. I am not a philosopher or someone looking for ultimate truths or breathtaking revelations. What I am after is something I can get by with, so that I am able to get on with my life in the way that I am used to: because at the moment I am having difficulty getting on with anything. At work I sit listlessly at my desk, toying with a pair of scissors, snipping meaningless shapes in the air, unable to concentrate. June, my secretary, has never seen me like this before. She suspects that I am lovesick and brings me steaming cups of tea at regular intervals.

‘Thank you, June, but I’ve just had one,’ I say. I raise my hands. ‘Really, I’m fine.’

She will not be deterred. ‘Drink, it will do you good,’ she says, bossily pointing at the cup. ‘Come on now.’ She stands there, arms folded, watching me. I drink.

‘Thank you, June. That’s a lot better,’ I say weakly. When she has gone I return my gaze to my work. Again the print fuzzes over and once more my eyelids weigh kilograms. Again, after leafing through a few pages, I am exhausted and have absorbed nothing.

I will not dwell further on these symptoms, which anyone who has ever worked in an office will recognize. The important thing to note is that never before have I been afflicted in this way. The experience is, for me, unprecedented, and therefore doubly alarming – I, who am so happy in my work, struck down like this!

I must without delay go back to Friday, 9 September 1988 – the day, you could say, when I first began to be hauled from my element and enmeshed by Donovan’s quickly unspooling life.

That Friday I travelled to work on the underground. As usual I was reading a newspaper as the carriage hurtled through the tunnels towards the Embankment. Just before we reached my stop (we were slowing down under the riverbed) I read the following piece in a column of ecological chit-chat:

As anxiety grows over the planet’s dwindling ozone layer, attention has centred on the case of the European Commission v. The United Kingdom. The argument in the European Court concerns the alleged failure of the government to implement EC directives restricting the use of carbonfluorochlorides (CFCs), substances which, it is thought, damage the ozone layer. The resolution of the dispute has been delayed by an unforeseen snag. Yesterday counsel for the government, Michael Donovan QC, suffered a collapse when he rose to address the court. Proceedings have been adjourned for a replacement for Mr Donovan to be instructed.

Michael Donovan: the name jumped at me from the page. Donovan, collapsed?

Before I had time to consider the matter further the tube clanked into the station, a booming voice warned Mind the gap and I had to fold up my newspaper and alight. On my way to work – on the escalator up to the surface, on the gradient past Charing Cross Station up to the Strand and during the three minutes of walking after that – I gave some thought to Michael Donovan for the first time in years: probably two, maybe even three years. Our lives had diverged, and for a long time now we had moved in different circles. That said, there had remained the occasional intersection. I had, naturally enough, seen his name from time to time in the newspapers and in the law reports, and once, years ago now, I had glimpsed him at a function, something which caused me a certain amount of discomfort. Socially, I am unskilful, and one of the consequences that flow from this is that a drinks party usually finds me in a corner listening, reluctantly but inescapably, to a person whose conversation I find uninteresting. A second consequence is that I am filled with uncertainty when it comes to greeting demi-or semi-acquaintances. The degree of warmth or recognition called for by the encounter eludes me completely – is a handshake and a brief conversation necessary, or will a raised, friendly eyebrow suffice? The matter is aggravated if, like Donovan, my acquaintance is more senior than me. Should I, the lesser of the two, humbly make the first move? Or would that not be a little presumptuous?

I find that I am straying from my point, which was that I was not entirely happy bumping into Donovan. This is not surprising (that I have strayed, I mean), because I have never undertaken this kind of enterprise before. Although, due to my training and occupation, I am an adept chronologist, I am not a natural recounter. If, at some gathering, I am casually relating some inconsequentiality or other, and I notice that a silence has descended around me and that suddenly I have an audience, almost invariably I freeze up and forget the point of what it is I am saying and it all ends badly, in blushes.

As I was saying, I did not relish it when Michael Donovan crossed my path (more precisely, when I crossed his path – Donovan was the man with the path; me, I have not done it my way, I have gone the way of others). Walking into the building where my office is situated, waiting with a cluster of others for the elevator to descend to the ground floor, I painfully recalled the last time I had spoken to him.

The encounter had taken place seven years before, in 1981, at a party in the Temple. To put myself at ease (it was one of those burdensome gatherings filled with partial acquaintances and characterized by a lot of hesitant eye contact) I had drunk quite a few flutes of champagne. Suitably uninhibited, I spotted Donovan talking to a group of people and felt no trepidation about approaching him, even though it had been some time since we had last met.

The group he was with was bunched into a tight phalanx of suits, and I had difficulty in joining them. I hovered around the perimeter of shoulders for a while, waiting for a chink to appear in the ranks, and just as I was beginning to feel a little foolish one of the suits drifted off and I was able to slip in. I remember chipping into the general conversation with the odd well-received remark and gradually I gained the confidence to speak to Donovan personally when a lull came in the talk.

‘Well, Michael,’ I said, ‘how are things?’

Everyone looked at me. Everyone stopped what they were doing.

Donovan said, ‘Very well, er –. How are you?’ He gave me a blank, though not unfriendly, look. Then he smiled politely. ‘How’s the, er, work getting on?’

It was obvious to me, and to everyone else, that he did not have a clue who I was, or what I did – in fact, he looked at me as though he had never met me in his life! Now, although I never forget a name myself, I can well understand that a person like Donovan, a big fish, has better things to do than remember all the small fry he has ever met, the plankton of casual acquaintances. He has other things on his mind, he has global problems to crack, issues that affect all of humankind. But forgetting me – this was truly extraordinary. I was small fry, yes, I would be the last to deny it – but I was also his former pupil! Only three years previously I had spent six months tête-à-tête with him, locked in collaboration, my side by his side. It was a time of extreme proximity and affiliation. For six months I carried his papers and tidied his room, for six months I researched his opinions, made his coffee, drafted his pleadings and operated his telephone. For half a year I was an indispensable, if extricable, part of his practice – if not his right hand, or even his fingers and ears, then his shoe-laces, his cuff-links. He had counted on me, and in my humble way, I had counted for something.

Since that time my appearance had stayed roughly the same. Admittedly, my hair had thinned somewhat and my face had accrued more flesh – but it was not as if I had grown a moustache or dramatically changed my accent. I had, moreover, dropped him a note from time to time to keep him up to date on my progress. (How stupid of me! I cringed at the memory of those letters, their earnestly informative, self-important tone …) How, in all these circumstances, could it be that I, or something about me – my voice, my manner, the way I looked – rang no bells?

‘Fine,’ I said, ‘fine.’

There followed an unhappy, a miserable, hesitation. We both looked about the room, brimming with chortling lawyers, to avoid one another’s eyes. The other members of the group exchanged glances. I felt ridiculous. Although, as a rule, I am more than content with who and what I am, the incident was nevertheless an unhappy reminder of my unimportance in the legal world. The moral was clear: Donovan was out of my league now. I had no business talking to him. I swallowed wretchedly at my glass. It was empty. When I looked up I sensed that everyone was waiting for me to say something, and I noticed Donovan’s eyes were flickering around the room, searching for a getaway. I decided to act, it was time to put an end to this torture.

‘Well, it’s nice seeing you again,’ I said, and clumsily wandered off at the wrong moment, just as Donovan opened his mouth to reply. I turned round to repair my error but it was too late. Along with the others he had turned his back and doubtless had already purged the incident from his mind.

What Donovan had forgotten was that my name is Jones, James Jones. It is a plain, transparent name and, until an unrelated namesake induced a mass-suicide in Guyana, was an unremarkable one. I am a junior partner in Batstone Buckley Williams, an unprestigious firm of solicitors in the West End of London. I have a general, unspecialized practice: quite a lot of personal injury, family, some landlord and tenant, conveyancing, the odd bit of crime. I think it is true to say that, by commonly accepted standards, I am not an especially successful lawyer. I do not regret this, as professional success is not something I set great store by. Of course, it would be nice to wake up in the morning a highly paid and famous lawyer, respected and admired by my fellow men – given that option, I would take it like that, in the click of two fingers. But the pain of actually achieving that type of standing, the sacrifices, the boredom – these are not for me.

By contrast, for those of you who have not heard of him, Professor Michael Donovan QC was, in the autumn of 1988, one of the most triumphant practitioners at the English Bar. He was easily (there is no doubt about this) the top international lawyer in these islands, the possessor of a world-class legal mind. That mind of his … It was naturally and freakishly powerful, like a once-in-a-blue-moon tidal wave, or a tree-plucking wind in England. Perhaps this is a pedestrian or fanciful metaphor, but I most easily visualize it as one of those fat Swiss army penknives, deceptively stocked with cutthroats and instruments of severance, disassembly and dissection: razors, scissors, corkscrews, bottle-openers, screwdrivers, magnifying lenses, the lot. In a flash, before you could mobilize a brain cell, he would have dismantled an issue, anatomized its components and analysed its implications. He had all the intellectual tools, and this showed, this shone, in his writings. He was a great academic – innovative, controversial, scholarly – a star. He wrote his books and articles in a simple, transparent style, using short, pithy sentences, which meant that apart from anything else, he was immensely readable. He was the M. J. P. J. Smith Professor of International Law at Cambridge University, and his publications excited interest and envy around the world.

Donovan, then, was equipped for any contingency of legal warfare. For myself, I can safely say that he was the most brilliant court lawyer I have ever seen, and probably the most feared as well. His advocacy, whether in court or at the negotiation table, was – I was about to say brutal, but that word has connotations of crudeness that would not be quite right – inexorable. I for one have never seen anything like it. The only feasible comparison I can think of is with the American heavyweight boxer Mike Tyson. If you have seen this man boxing in his prime you will know what I am talking about. He is not especially tall, so it is hard to pick him out in the crush when he pushes through the bodyguards, photographers and spectators that crowd him on his way to the ring. But when he finally stands disrobed and gleaming in the floodlight, he is unmistakable: black, baggy silk shorts, long bludgeoning arms and eager, focused eyes. Then the bout: some combinations to the torso, an uppercut, then bam – a sickening bullseye to the jaw, and Tyson’s opponent is on his back, seeing stars.

I am not suggesting that Donovan’s entrée to the courtroom was the same as Tyson’s to his forum, or that he disposed of cases in a matter of minutes; but Donovan, like Tyson, had a capability unhesitatingly to unleash inimitable, efficient destruction. He would immediately detect any flaw in an argument, spontaneously expose it, and then carefully cudgel it with spot-on, shuddering verbal blows. There was no holding back, but nor was there vindictiveness: personal feelings, emotions, did not enter into it.

I must return for a minute to what I have roughly called Donovan’s inexorableness. It marked everything he did. His actions had an unrelenting shape to them, the shape of things to come. He was streaming forward at such a speed, and so unerringly, that his future seemed a foregone conclusion.

TWO (#ulink_dbe3258c-7eec-58de-b798-ee8d0d160973)

In short, then, reading that item in the newspaper turned my thoughts to Donovan for the first time in a long time. Going up to my office that morning in the full-up elevator, I worried about his well-being. Collapse? What was it, heart? Stroke? At his age? In his mid-forties?

When I had ascended to the fourth floor I stepped quickly into my office, preoccupied by the business. I helped myself to a black coffee and sat in the chair behind my desk. It was half-past eight, I had about half an hour to myself before everyone would come in. So Donovan had collapsed on his feet, I thought to myself. What did that mean, collapsed? I tried to imagine it: had he fallen over the lectern clutching his chest, powerlessly splashing papers everywhere? Or had he buckled at the knees and slumped to the floor, folding up like an old deckchair? What had happened?

I decided to telephone his chambers at 6 Essex Court to find out. There was no need for me to look up the number because after all these years I still knew it by heart – 583 9292.

I stopped dialling and put the receiver down at 583. It did not feel right – it was too direct, too embarrassing. I would have to find out in due course, the same as everyone else. It was not as though I was a particularly close friend of the man, or family, or especially connected to him. In fact, Donovan did not even know who I was any more.

Of course, there had been a time when Donovan did know me, when he knew exactly who I was. I am thinking of my time as his pupil barrister.

My whole pupillage lasted for a year, and it was the second part of that year that I spent with Donovan. My first six months had also been spent at 6 Essex Court, but with a different pupil-master, a man called Simon Myers. Head of chambers at the time was Bernard Tetlow QC (later, of course, Lord Tetlow of Herne Hill). Six Essex was just as fashionable a set then as it is now. The work flowing through chambers was high-class commercial law: shipping, reinsurance, private international law, banking and so forth. There was no crime, no family, no landlord and tenant, no dross whatsoever. The pigeon-holes of the tenants bulged with lucrative briefs from Linklaters & Paines, Slaughter & May, Freshfields and Herbert Smith, the papers wrapped like offerings in their bright pink ribbons. You certainly would never see any work from my firm, Batstone Buckley Williams, floating about the place.

Simon Myers, my first pupil-master, was good to me. Myers was very punctilious and he scrupulously took pains to ensure that I was properly trained. He gave me some useful habits of mind which to this day hold me in good stead. ‘Always ascertain the facts. Visualize what has happened: imagine the people sitting down to write letters. Remember dates. Always make up your own mind about something. And remember, never give a definitive answer to any question: always express clearly the subjectivity of your opinions. Use qualifiers to hedge your bets: “In my opinion, in my view, in my analysis, as I see it, from my perspective.” Sprinkle your sentences with phrases like “it follows that” and “accordingly” and “therefore”. They lend a veneer of logical force to your argument.’ There were also tips of a more general nature. ‘Look sharp: a tidy appearance betokens a tidy mind. Here, take this.’ He handed me a card. ‘My tailor. Get yourself a new suit. And this.’ Another card. ‘My financial adviser. And this. My stockbroker. Get yourself a pension, you won’t regret it. Get yourself a portfolio. And while we’re on the subject of investments,’ Myers said, drawing a ten-pound note from his wallet, ‘here, go put this on Royal Burundi to win the 3.30 at Haydock. You’d do well to invest a pound or two yourself.’ Then the golden rule: ‘Look the part. No matter what, always look as though you know what you’re doing.’

Simon Myers liked me and recommended to the head of chambers that I be seriously considered for a tenancy. It was for this reason, I think, that I was allocated to Michael Donovan for my second six months of pupillage. They wanted to stretch me, to see what I was really made of.

Donovan had his own specialist, personalized practice – public international law with a sideline in private international and European Community law. That is not to say that he possessed a narrow expertise – not Michael Donovan. Even in areas of the law he was supposed to know nothing about, like defamation or insolvency, he would run rings around the specialist practitioner, tantalizing him with far-fetched hypothetical that would push a principle to its limit and then, after the other had given up or had proposed an inadequate solution to the problem, he would supply an elegant analysis that seemed, in retrospect, blindingly obvious.

So it was an enormous privilege to work alongside Donovan. When I say alongside, I do not mean physically, although my desk was in his room, next to his desk. In fact we saw each other rarely – it was not often that we actually laid eyes on one another. Most of the time Donovan would be away, usually overseas, at an arbitration or conference, and I was left to hold the fort in chambers, turning over paperwork and manning the telephone. But no matter how far away Donovan was, we never lost touch. It is not just that we spoke daily by telephone, no, our communications went deeper than that. I knew what he wanted without his telling me, I anticipated his every unspoken wish. It was as though some wire, some humming conductor, ran between us.

And so I was his anchor man. I laboured night and day for him, unobtrusively ensuring that everything ran smoothly on the home front. Saturdays and Sundays would find me alone in chambers, poring over the books in the basement library until late into the night, my desklamp the only light burning in the Temple, my face on fire. I worked like crazy. No one at Batstone’s would believe me if I told them, but in those days I never stopped. The responsibility was not just stimulating, it was like a dynamo, shooting wattages through me that I have never known at any other time in my life. In the mornings I would shake off the reins of tiredness and feel a great horsepower pumping up inside me. My work was my reward. When an opinion or pleading I had devilled for Donovan went out unchanged bearing his signature, far from being displeased or resentful at this exploitation of my free labour (like most other pupils, I was unpaid), I was gratified – to think that I, James Jones, had produced a work worthy of the brilliant Professor Donovan!

In my new state of excitement I became fired by ambition – real ambition, not just wishfulness. I desired that tenancy at 6 Essex like nothing else – more than anything in the universe I wanted my name, Mr James Jones, up on the blackboard bearing the tenants’ names in white paint. I would envisage each letter of my name there when I walked in every morning, fantasize over each brushstroke. It would happen, I knew it would; my visions were so vivid that they could only be premonitions. I knew the room I would occupy down to the last detail, down to the paintings I would buy to hang on the wall. My future was under my belt. It all made sense, it all fell into place: sometimes I would awaken from my work and suddenly the ineluctable nature of my situation would be revealed to me: of course, I would think, this is it. This is how it was meant to be.

Looking back on my time at 6 Essex afresh, I think that I was perhaps too unobtrusive, too quietly efficient, too mole-like, for my own good. Just recently I saw a documentary about moles on the television. Moles work night and day. They never rest. If they are not paddling out fresh corridors of earth they are maintaining their existing galleries and tunnels, snapping and crunching intruding roots and mending the walls. The point is, most of this was not known until they sent down one of those fantastic subterranean cameras. Before that happened, the moles received no credit for their industry. For all anyone knew they were bone idle. Likewise, if I had been a little more prominent about my efforts in the basement, if my profile had been a little higher, then perhaps, just maybe, I would have been offered a tenancy. But I thought there was no need for self-promotion. I thought that Donovan would recognize my worth and stand by me when the decision came to be made as to which one of the seven pupils would be taken on. I thought he would say, Consider Jones, he hasn’t put a foot wrong in six months. I thought he would say, Jones: look no further than Jones.

But no. When the chambers meeting came around Donovan was in Alexandria, with the result that at the meeting there was no one in my corner, no one rooting for me. Oliver Owen was taken on, I was not.

The afternoon that the axe fell I was in the chambers library with the other rejected pupils. All six of us were seated around the oval central table while we numbly contemplated our Weakening futures. Oliver Owen was at El Vino’s with the head of chambers, celebrating.

Then Alastair Smail, the head of the pupillage committee, the man who had made us and broken us, entered the library, whistling a tune through his bright pink lips as though nothing had happened. After searching and craning among the bookshelves he turned round and asked whether anyone had seen Westcott on Trusts anywhere. Receiving no reply, he went energetically through the borrowers’ index, fingering the cards and commentating loudly on his progress. Then he looked around and sensed, for the first time, the gloom. ‘What’s the matter with everyone? It’s like a funeral parlour in here,’ he said, leaving without waiting for an answer.

While the others just looked at each other, I got up and followed him, eventually catching up with him in the corridor outside. I needed to speak to him urgently about getting a pupillage elsewhere, in another set of chambers. I had neglected to take precautions on that score (my work had taken up all my time), and there was a real danger that I would miss the boat completely if I did not act quickly.

‘Alastair, I wonder if I could have a word with you.’

‘Yes, of course,’ he said, still walking.

‘About finding somewhere else,’ I said. ‘I was wondering if you might know anywhere where there might be some space – for me.’

He looked at me with a strange expression. ‘I thought you had somewhere. I thought you’d organized something.’ Now I looked at him: where did he get that idea from? ‘I do know some people, yes, but you realize that, well, that the other pupils do have – priority.’

What? ‘Priority? Why?’

‘As tenancy applicants, they have priority over pupils who made no such application. You appreciate that, Jones.’

‘But I am an applicant, too,’ I said. ‘I applied for a tenancy too.’

‘Did you?’ Smail said. ‘We received no such application from you. We assumed you had made other plans.’

‘But I did apply,’ I said. I could not believe what I was hearing. ‘I did apply.’

Again Smail looked at me with a strange expression. ‘Well, we received no application,’ he repeated. ‘Nothing at all.’

‘I didn’t send anything in writing, that’s true,’ I said desperately. ‘But I wasn’t aware that a formal application needed to be made. I thought the very fact that I was here as a pupil was in itself an application. No one told me that I needed to apply formally.’

‘Nobody told you? Michael didn’t tell you?’ I shook my head. Smail shook his head too. ‘Well, this is unfortunate. And you wish to apply, do you?’

I said, ‘Yes.’ I said, ‘Yes, if it’s not too late.’

Smail thought for a moment. ‘Leave it with me,’ he said. ‘I’ll get back to you as quickly as possible. Don’t worry,’ he said with a smile. ‘We’ll sort something out.’

‘Thank you Alastair,’ I said. I meant it, I was full of gratitude: perhaps all was not yet lost! Perhaps I was still in with a chance, after all! ‘Thanks very much,’ I said. ‘I’m sorry about all this, but I really did not know about the need to apply.’ Smail gave me a smile which said it was quite all right, and walked away.

The next day I received the following letter at home. It was a standard letter which began with Dear…, and with my name, Jones, inked in over the dots.

Thank you for your application for a tenancy in these chambers. It is my sad duty to inform you that, after careful consideration of the merits of your application, we are unable to place you on the short list of candidates. We wish you every success in the future. Yours sincerely,

Alastair Smail

Soon afterwards I began sending off applications to other chambers. The only pupillage I was offered was with an obscure landlord and tenant set, and they made it clear that they doubted very much whether they would be able to take me on at the end of it. It was not me, they said, it was simply a question of space: there were just not enough square feet to go round. It was then that I saw an advertisement inviting applications to Batstone Buckley Williams. I attended a brief interview and they immediately offered me a position. Of course, I gratefully accepted. The Bar had, by then, lost its appeal for me. The senior partner at Batstone’s, Edward Boag, took me aside the first day I arrived. We went into a corner together and he gave me a piece of advice. ‘I want you to forget all the law you’ve ever learned,’ he divulged. ‘We don’t like intellectual pretensions at Batstone Buckley Williams. And let me let you into a secret.’ He looked around in case anyone was listening. ‘This business is all about one thing: meeting deadlines. Lots of them.’

I must make it clear that I do not feel bitter about the experience – not in the slightest. I am very happy here, at Batstone Buckley Williams, and in many ways I am relieved that I never stayed at the Bar – the pressure and the workload are simply too great for my liking. And certainly I have no hard feelings for Donovan. It was not his fault that I was not taken on, he was abroad at the time of the decision. A man cannot be everywhere at once: omnicompetent, yes, but not omnipresent. If I were as busy as Donovan, I too might well overlook such things as tenancy selections, or simply find myself unable to devote myself to them, however much I might wish to.

So I took no pleasure in the news of Donovan’s collapse. I did not rub my hands in glee at his misfortune or count my lucky stars. No, I thought of him with fondness and was anxious about his health. I was also, well, intrigued. The boundary line between my sympathy and my curiosity was, it must be said, a little indistinct.

But when nine o’clock came around and the telephone began ringing and my colleagues started arriving, my thoughts soon turned to other things. A terrible pile of papers awaited my attention and my agenda was awash with appointments, the conferences, meetings and deadlines flowing in waves of bright manuscript across the pages. My secretary, June, notes down my engagements in my diary using an ingenious scheme of red, green and turquoise inks which I have never been able to understand. Her method is so painstaking, though, that I do not have the heart to tell her this. Anyway, I am sure that my diary is a lot more agreeable than it would otherwise be and I am grateful to June for the trouble she goes to. Without her I would be lost, because I can, sometimes, be something of a dreamy, head-in-the-clouds type of man. I have been known to moon away an afternoon revolving in my chair, mulling over nothing in particular, listening to the traffic below my window, the relaxing grumble of engines and the sounds of the klaxons (once I spent a whole afternoon classifying these as toots, beeps, blasts and honks – the toots outnumbered the beeps, but only just).

Other times I take a ladder to my mind’s attic to take a look for anything interesting. I climb up there and rummage around old trunks filled with all kinds of bric-à-brac: I never know for sure what will turn up. For better or worse my head is full of trivia, odds and sods that bear on nothing – the cost of wholly insignificant meals, the names of plumbers no longer in business, the lyrics of bad songs, examination questions on Roman law that I never answered, telephone numbers of women I shall never see again. Some people can simply discard these things like leaky old armchairs or out-of-date suits. Not me. When it comes to the past, I am a real hoarder, salting away every moment I can, even those possessed of only the minutest value, their historicity – the banal fact that they have occurred and will never recur. The difficulty with this is that things stick indiscriminately in my mind; that important things are apt to be lost amongst bagatelles.

All of this does not mean that I am sentimental or prone to nostalgia. On the contrary. I have no wish, on the whole, to turn the clock back, nor do I entertain any notion of the good old days. As far as I am concerned, what is done is done. Admittedly, like everyone else, I do sometimes enjoy reliving certain moments. Sometimes, in a kind of reverse déjà vu, I find in myself the exact feelings and sensations that coursed through me at a particular time, so that for a minute I am, my lurching heart and tingling nerves registering a physiological journey, utterly transported: but that is all.

If my mind is a store-room full of junk, Donovan’s was something altogether different. Unlike me, who can barely remember the name of a single case, Donovan’s brain housed a huge repository of legal authorities which he could instantly cite; it brimmed like a grain-bin with sweet precedents and nuggets of jurisprudence. He had a party trick where, if you quoted a case to him, he would rattle off the ratio of the decision, the year, the judges and barristers involved and even, if the case was remotely near his field, the page where it appeared in the reports. Everyone used to look on open-mouthed. No one could understand how he managed it. I know that science has uncovered some mnemonic freaks, like the Russian reporter who, with only three minutes’ study, could learn a matrix of something like 50 digits perfectly and years later could still churn out the matrix without error. This man could memorize anything you threw at him: poems in foreign languages, scientific formulae, anything. It made no difference whether the material was presented to him orally or visually or whether he had to speak or write the answers. His trick, I read somewhere, was to associate images with whatever it was he was trying to remember – in the way that you might, in trying to remember a shopping list, visualize a pig in a tree so that you do not forget to buy pork. Donovan’s memory was not, I think, quite as phenomenal as the Russian’s; but where he left the Russian behind was in the use to which he put his memory, the way he subjugated it for his own purposes. Donovan always had his facts carefully marshalled, he never allowed what he knew to get in the way of his thinking. The Russian, by contrast, found that his memory subjugated him; his mental imagery was so vivid that it fouled up his comprehension, so that the meaning of a sentence like ‘I am going to buy pork’ would be lost in a surreal collision of pigs and trees.

What I want to know is this: how is it that, with all his powers of recollection, Donovan could not put a name to my face at the party? I will go further: how is it that he could not even put a face to my face, that he failed even to realize that he should have known my name? The man was a walking reference library. Surely he could have accommodated me in his mind’s chambers? Surely, at the very least, he could have offered me a tenancy in his remembrances?

THREE (#ulink_1f7f676a-ad84-582b-bb28-d081722e6158)

Three weeks after I had read about Donovan’s collapse I was drinking vodka and tomato juice at the Middle Temple bar. I am not a regular there by any means, but if I drop in I can usually find someone to talk to; if not, I am happy to crunch a packet or two of dry roasted peanuts and read the newspaper.

On this occasion I was leafing through the sports pages when I recognized Oliver Owen sitting by himself on the sofa next to mine, looking incongruously splendid on the faded, bashed cushions. It was the first time I had seen him in years. His washed straw hair arced from his forehead in two gorgeous fountains; his parting cut purposefully through his hair, clean as a road in a cornfield, as though it led to some significant destination. Oliver was wearing a charcoal double-breasted suit that had visibly been tailored to accord with his specific instructions. Golden nodules linked the cuffs of his dry-cleaned white shirt and a handkerchief spilled emerald carefully from his breast. I searched my mind for the word that best described him and came up with it – dashing, Oliver looked dashing.

Like me, Oliver was reading a newspaper. I wanted to speak to him. We had been good friends for a couple of years after we had met in pupillage, and it was only circumstances, and not our volition, which had prevented us from seeing each other since then. Even now, I felt, our friendship was not over but merely dormant.

But I stayed where I was; something in me, some ridiculous internal prohibition, prevented me from leaning over and greeting him like the old friend he was. He’s probably got an appointment, I thought, he has the air of someone waiting for another; and did he want to speak to me anyway? Why should he, after all this time? What would we have to say to each other?

‘James?’

‘Oliver,’ I said, putting down my reading. I was delighted.

‘Why don’t you come sit over here?’ Oliver invited. ‘My God, it’s been years. How are you?’

I told him how I was (fine) and asked if he wanted a drink. I went up to the bar and showed Joe two fingers. Two large bloody marys please, Joe.’ While Joe mixed the drinks I unintentionally caught sight of myself in the mirror behind the bar. I say unintentionally because, for my peace of mind, I do not look into mirrors unless I have to. Comparing my image with Oliver’s eye-catching reflection, I was reminded that I am a man of almost transparent appearance, a man whose presence you would not quickly register in a public place, and in the mirror my face was struggling to make an impact between the brightly labelled bottles of Cinzano and Smirnoff and Gordon’s gin and Glenfiddich. My pointy and virtually hairless head poked out anonymously, my eyes, nose and mouth small and mistakable. My most distinctive feature, if I am truthful with myself, is a strange one: there is an uncanny symmetry between the tramlines on my forehead and the parallel lines made by my chins on my neck, with the net result that the top half of my head is just about duplicated in the bottom. You could turn a sketch of my head upside down and not notice the difference.

The drinks arrived and Oliver joined me at the counter as I spooned chunks of ice into the drinks. ‘So,’ he said, taking the glass I handed him, ‘what are we up to these days? Still with, er …?’

‘Batstone Buckley Williams,’ I said. ‘Yes. How about you? How’s 6 Essex?’

‘Awful,’ he said. ‘I’m spending far too much time in bloody Hong Kong and Malaysia. I hardly have a moment on home turf any more.’ We paused and drank from our glasses. Oliver looked at us in the mirror. The contrast was embarrassing. ‘You’re looking well, James,’ he said with a smile. He patted my lumpish stomach. ‘But what’s all this? What happened to that sheer wall of rock? Turn round, let’s have a look: dear me, it looks to me like there’s been some kind of landslide.’

I pulled my waistcoat down over the bulge and shrugged. ‘You’re looking well too,’ I said.

‘Who, me?’ Oliver inspected his image in disbelief. ‘I’ve aged, James, aged. Look at me, ‘I’m a wreck. It’s marriage, it wears you down. You married?’

‘No,’ I said.

‘Two kids, house in Putney,’ Oliver said with intentional banality. ‘Yes, you’ve guessed it: dog, school fees coming up. After a while, the statistics start to catch up with you. Amazing how it just happens, isn’t it?’

For a moment I feared the talk would turn in detail to the question of educating the children, a subject I am rarely anxious to pursue. It was time to change the direction of the conversation. Happily, something came to mind.

‘What’s all this I read about Michael collapsing? Is he all right?’

Oliver laughed. ‘Collapse? Where did you read that? Collapse isn’t how I would describe it.’

‘Oh?’

‘Do you want to know what really happened? It’s not a bad story, I suppose.’ Oliver paused as he shaped the anecdote in his mind. He was still a gregarious man, a natural for company. ‘OK, here it is. Michael’s in big trouble. For twelve days he has to listen to Laurence Bowen putting the European Commission’s dreary little case that we’re not complying with their regulations about the ozone layer. Can you think of anything more boring than refrigerators and their relationship with the stratosphere? No, neither can I. Day after day, detail after boring bloody detail. Each day, each minute even, is a struggle with sleep, with madness.’ Oliver swallowed some more bloody mary, pleased with his phraseology. ‘Anyway, by the time it’s poor old Michael’s turn to say something, his case is about as intact as the ozone layer. Those points made by Bowen have been eating away at his ground like bloody CFCs. In short,’ Oliver summarized, ‘the UK’s in big, big shit. We need a bloody miracle. The only consolation for the government is that if anyone can do it, it’s Michael. All eyes turn to him as he stands up. What’s he going to say? everybody’s asking. How’s he going to play it?’ Oliver stopped. He saw my expression and grinned.

‘And?’ I said eagerly. ‘Go on.’

‘Only if you get me another,’ Oliver said. ‘Same again please.’

Smiling, I ordered two more of the same. Oliver had not changed.

‘Go on,’ I said, when I got back. ‘Get on with it. Michael stands up to reply: what does he say?’

Oliver grinned again. ‘Nothing.’

‘Nothing?’

‘Not a squeak. All they get is a leaden, ungolden silence. He moves his lips and waggles his tongue but not a word comes out. Not a syllable. He’s speechless, he’s mouthing like a bloody goldfish.’

‘You’re joking,’ I said encouragingly. ‘You’re pulling my leg.’

Oliver laughed. ‘James, I swear to God, it’s like something out of Harold Pinter. Michael’s just standing there shuffling his papers, completely dumbstruck.’

I shook my head. ‘Michael? Lost for words? I don’t believe it.’

‘He’s not lost for words,’ Oliver corrected me, ‘he’s lost for a voice. You can imagine it: the judges are looking at each other, baffled as hell. They’ve never seen anything like it in their bloody lives. “Professor Donovan, is there anything the matter?” Donovan points at his throat. “Usher, fetch the professor a glass of water.” Enter water bearer. Donovan drinks. He opens his mouth to speak: still nothing. My God, you can imagine the embarrassment all round.’

‘What happened?’

‘Well, they adjourned of course. Sent everybody home. What else could they do?’

‘Well, how strange,’ I said. ‘What an odd thing to happen. It sounds quite serious, actually. What was it, do we know? You don’t just conk out for no reason.’

Oliver saw some blemish in the sheen of his left shoe and awkwardly rubbed the toecap on his trousers. You could tell that he was right-footed. ‘James, sometimes I despair at your naivety,’ he said with an exaggerated casualness. He looked up from his shining feet and gazed straight into my eyes, without expression.

I gasped. ‘You don’t mean … Are you saying that Michael …?’

Oliver leaned forward to murmur. ‘I’m not saying anything, James, ‘I’m saying nothing at all. But let me put it this way: the government is not exactly prejudiced by the adjournment, is it? All that extra time to reconsider the points against it? Handy, I’d call it.’

This was typical Oliver, scurrilous, slanderous and entertaining.

‘That I don’t believe,’ I said. ‘Michael would never stoop to such a thing.’

Oliver leaned his back against the bar, looking to see who was around. He raised his faint eyebrows at a passing friend and turned his face towards me once more. ‘You believe what you want to, James.’ Then a thought seemed to strike him. ‘How about another?’ He gestured at Joe.

‘I mean, what’s he been like since he got back?’ I asked.

‘Well, he came back to chambers straight away and sat down to work as though nothing had happened. This is about three weeks ago. The only problem was, he found that he couldn’t write either. As a counsel, he was completely kaput.’

‘Couldn’t write as well as couldn’t speak?’

‘James, you’ve hit the nail on the head.’ Oliver patted me on the back by way of congratulation.

‘Well, what did he do?’

‘Not much. He just sat at his desk, hunched over his papers, good for nothing – he wasn’t even able to answer the phone. Completely incommunicado. After a day or two he went home, presumably to look for his tongue.’

‘So he wasn’t faking it, after all?’

‘I never said he was. But before you make up your mind, don’t forget it would have looked rather odd if it had been business as usual as soon as he got back, wouldn’t it?’

I said, ‘So you think it’s all an act, do you? You think Michael’s having everyone on?’

‘James, whatever gave you that idea?’

‘Well, I don’t agree. It all sounds incredibly far-fetched to me. If anyone found out, he would be disbarred. Besides,’ I said, ‘it’s not his style. It’s not like him at all.’

Oliver made a tolerant face. ‘With respect, James, how well do you know Michael? When was the last time you spoke to him, or saw him in court? Things have moved on since you were his pupil.’

Reddening, I said, ‘Michael would not have done such a thing. He’s got too much intellectual integrity – he has standards.’ I put my lips to my glass to drink and then stopped to speak. I was whispering, in case anyone overheard the content of the conversation. ‘With his brains he doesn’t need to resort to that kind of trick. Michael? Going through a charade like that? Are you mad? We’re talking about one of the best lawyers in the world, for heaven’s sake, not some under-prepared hack.’

Oliver laughed loudly, as if I had said something funny.

‘What is it,’ I said, beginning to laugh myself. ‘What have I said?’

‘Nothing, James, nothing,’ Oliver said, still tittering.

I smiled. I still could not see what was laughable. ‘So what’s the situation now?’ I said.

‘Funnily enough, he came back to chambers today, singing like a nightingale.’ Oliver read the time on the clock. It was half-past seven. ‘On the subject of birds, I’ve got to go back to my cage, before I get into big trouble. James,’ he said, reaching for my hand, ‘we’ve got to do this again.’ With that he swallowed what remained of his drink, thudded his glass against the surface of the bar, winked, and strode off with his bouncing, light-filled head of hair.

Outside it was drizzling. I decided that the best thing to do about food was to go to eat a quarter-pounder and fries at the McDonald’s in the Strand, near Charing Cross. I tramped up Middle Temple Lane and past 6 Essex Court, my hands in my pockets. There was Oliver’s name, about half-way up the tenants’ blackboard. I walked on. There was no need for me to look. I knew that blackboard by heart, especially those names daubed on it after I had left the chambers: David Buries, Neil Johnson, John Tolley, Robert Bright, Alastair Ross-Russell, Paul St John Mackintosh and Michael Diss glowed in my head in big mental capitals like the neon names of the theatre stars illuminating the Strand on my walk to McDonald’s. There was a time when I would have wondered why I, James Jones, went incognito while these people, on the whole no more able than I, enjoyed this billing – but those sentiments were far behind me, and in any case I was relishing the meal ahead. When it comes to food I am not very choosy. I rarely cook – unless you count heating up tinfuls of mushroom soup or making salami and tomato sandwiches as culinary activities. Usually I dine at some cheap eatery or takeaway, not because I cannot afford anything better, but because I feel a little self-conscious, sitting in a good restaurant by myself, under the scrutiny of the waiters. Other nights I ring up for a curry or pizza to be delivered at my door: I eat with a tray on my lap and the television remote control by my side, and sometimes finish off a bottle of wine opened the previous night. My diet, then, basically revolves around cheeseburgers, shish kebabs, fried chicken, vinegared fish and chips, spring rolls, jacket potatoes and fillets o’fish.

A friend of mine of around this time, a girl called Susan Northey, used to lecture me on the deficiencies of my eating habits, drawing particular attention to the amount of saturated fats I consumed. According to her – and she was armed with all sorts of figures to support her case – I was on the way to a massive heart attack. Occasionally Susan would cook for me, but her efforts rarely met with success. The idea of preparing my food depressed her, especially if I arrived at her flat slightly late.

This happened the night after I had spoken to Oliver. It was a Friday night, and after we had finished eating she started crying.

‘Why am I doing this? I feel like a housewife. Jimmy, look at you, you’ve come in and sat down and wolfed your plate clean without a word.’

I stared guiltily at my plate. ‘Here, I’ll do the washing up. Leave that to me,’ I said.

‘I’ve got a migraine, my head feels as though someone’s split it open with an axe.’ Then she suddenly snapped. ‘Don’t touch those dishes, I’ll do them tomorrow.’

I said, ‘No, let me …’ but Susan angrily barred my way to the sink, so I retreated. I said, That was delicious, Suzy, thank you very much.’

‘It was terrible, it made me feel sick.’

‘Perhaps it did need a little more olive oil …’

‘I don’t believe what I am hearing: I cook you dinner and all you can do is criticize?’ She was furious. ‘Why don’t you cook, if you’re so good at it?’

‘I wasn’t criticizing, Suzy, I was just trying to be constructive. That was delicious, my love, I swear it.’

‘Don’t lie to me, Jimmy, I can’t stand it. It was terrible, and you know it. You just ate it because you’re a pig. You’ll eat anything you find in your trough.’

At this point I should have kept quiet. ‘Well, all right then, I’ve tasted better tuna salads,’ I conceded. ‘But there’s no need to get so worried about it, it’s only a meal. Let’s put it behind us, shall we? I’ll do the cooking in the future, all right? It obviously upsets you if you do it. Suzy?’

Susan was not speaking. She pulled on yellow rubber washing-up gloves and began brushing down the knives and forks that sprouted from her foaming left hand. I made a noise of protest but stopped when I saw her expression. Then I said something but received no reply. She just continued scrubbing down plates. I sighed: I hate scenes.

I decided to give it time and to wait quietly on the sofa. Hopefully things would blow over. Just as the programme on television caught my attention and I began concentrating on it, Susan spoke again. She said things were not working out and that perhaps it would be best if I went. I reflected for a minute and found that I agreed with her. There was little point in prolonging the evening. I collected my things and quietly left. I suppose that you could say that we broke up at that point. I walked to the tube station feeling – wonderful. Coasting along the buoyant pavements with a warm city breeze in my face and a navy blue, starred sky overhead, I felt I was being returned home on a yacht. I was breathing in and breathing out, and it elated me. It is a simple thing, my elation, but then again, is not quite as straightforwardly obtainable as it might sound. My life is so shot through with distractions, so plagued with interferences, that only rarely am I conscious of something as simple as the action of my lungs, of the fact that I, James Jones, am here, kicking around on this amazing planet. By avoiding the mazes of family life and the side-tracks of ambition, I have tried to take an undeflected, eventless route through the days, to dodge the clutter of incidents that bear down on me from every direction. There is only so much I like to have on my plate – too much at once, and everything begins to lose its flavour. When it comes to personal experiences, I prefer to eat like a bird.

It will be appreciated that, by my standards, this last year has been a complete blowout. On top of my usual diet of occurrences I have been forced to feed on the jumbled broth of Donovan, his father, Arabella, her lawyers, Susan and all their unpalatable, over-rich problems. It must be understood that I am not regurgitating all of these matters to indulge myself. It is not as if I am suffering from some kind of empirical bulimia. Despite the fact that, like most people, I enjoy the odd trip down memory lane, I am not one of these people obsessed with bygone days, those who compulsively inhabit the past as though somehow it housed the real world, as though newly minted, uncirculated days rolled around at a dime a dozen. No, you would not catch me relegating the solid, wonderful here-and-now in favour of the olden times. The only reason that I am chewing over these last months is that I want them digested and over and done with, because at the moment they continue to spoil my stomach for everyday things. The office seems drab and unreal, and still I am numb and listless and fatigued. So much so that June is beginning to show signs of impatience, and rightly so. She has enough to do without worrying about me.

‘Come on now,’ she says. ‘Stop moping.’

‘I’m not moping. I’m thinking.’

‘Well then, stop thinking then,’ she says. June will take no nonsense. ‘Start working instead. I’m getting a little tired of fielding these complaining phone calls.’

‘Who’s been complaining?’

‘Mr Lexden-Page for one. He’s rung three times this morning already.’

I groan, but this news does nothing to invigorate me. I take up my scissors and start snipping the thin air again. June thinks of saying something sharp but decides against it. Instead she emits a scolding humph! and struts back to her desk and clamorous telephone. But her disapproval has no effect on me. The fact is, my energies only return when I go back to these last months and, specifically, to the moment when Michael Donovan re-entered my life for real, in the flesh.

FOUR (#ulink_4c07be04-e279-5a57-a383-e92140072335)

On Friday night, then, Susan and I split up. The following Tuesday (4 October), I returned to the office from the kiosk where I buy the prawn and mayonnaise sandwiches I eat for lunch. On my desk June had left a list of telephone callers: Mr Lexden-Page, Miss Simona Sideri, Mr Donovan, Mr Lexden-Page again, and Mr Philip Warnett. Systematically I returned the calls (I derive a satisfaction from ticking these things off) until I reached the name Mr Donovan. Irritatingly, there was no message beside the name, only a telephone number.

‘June,’ I called over to her, ‘what did Mr Donovan want, do you remember?’

‘I don’t know,’ her voice came back. June sits out of my sight in an antechamber annexed to my office. From where I sit I can just hear the tip-tapping sound she makes on the computer keyboard and, if it is quiet, the small din of her teaspoon whirling sugar in her drink. ‘He just asked if you would call him back.’

Usually in such a case, when I have no idea who the caller is or what he or she wants, I leave the ball in the caller’s court and wait for a second communication. That day, however, I was anxious to get as much done as possible and scrupulously I dialled the number June had written on the scratch-pad. My call belled three or four times, then I heard the click of an ansaphone whirring into action. A throaty and charming voice, a woman’s voice, said, I’m afraid no one is in at the moment, but if you would like to leave a message, please speak after the tone. Bye!

I dislike these gadgets and leaving the frozen little communiqués they demand. I spoke stiffly into the mouthpiece. ‘Yes, this is James Jones of Batstone Buckley Williams. I am returning Mr Donovan’s call. Kindly contact me’ – I hesitated and, acutely aware of the irrevocable recording of my every silence, stumbled out an inelegant, incoherent finish – ‘if you wish to, to avail yourself of my, my firm’s services or otherwise.’

After that misadventure my face and torso felt hot, and I walked over to the kettle to make myself a coffee for which I had no thirst to take my mind off the incident. As I waited for the water to boil, my telephone sounded.

‘I have a Mr Donovan for you.’

I groaned to myself. He must have been using his answering machine to filter his incoming calls.

The voice said, ‘James, it’s me, Michael.’

Michael? ‘Ah yes, how are you?’ I said. Michael who? I thought.

‘James, I need your services. You do family law, don’t you? Matrimonial? You know your way about it?’

‘Yes, I …’

‘Good,’ he said, ‘then you’re just the man I need. When can we meet? Thursday – does Thursday suit you? Could you squeeze me in at, say, three o’clock?’

I was in danger of being steamrollered into an appointment with a stranger who claimed to know me. Then it clicked: that self-assured, irresistible tone? Surely not …

My tongue stumbling in my mouth, I said, ‘Excuse me, but I wonder if I might set something straight in my mind: I’m speaking to Michael Donovan of 6 Essex Court, aren’t I? It’s just that I have a bad line and I can’t hear you very well.’

‘The very same. Sorry, I should have explained; you’ve probably forgotten me after all these years.’

I laughed nervously. ‘No, no, no, it’s just that the line is poor … Now then,’ I said, changing the subject quickly, ‘Thursday you said? Let me just check. Yes, that would be fine.’ What was I saying? Thursday was not fine at all, the page in my diary was turquoise with meetings. Thursday was terrible. ‘Three o’clock? Yes, I can manage that. No problem at all.’

Donovan said, ‘Excellent. See you the day after tomorrow, then.’

The harsh tone of the disconnected line droned in my ear.

Michael Donovan! Michael Donovan had telephoned me!

My head suddenly weightless, I went to make myself that coffee, this time because I felt like drinking it. Back in my revolving chair with a hot mug warming my fingers, I spun round towards the window. I put my feet up on the window-sill, my toes in line with the rooftops across the road. I basked. So Michael had not forgotten me, after all. He knew that I was right here, at Batstone Buckley Williams. Joyously I swung my feet off the sill and walked over to the basin to rinse the coffee stains out of my mug. Of all the solicitors available to him, Donovan had turned to me. So, I had impressed him with my work. My long hours of painful, unpaid, meticulous research had made their mark, the mole had finally received his dues. Donovan remembered me, even after all these years, as someone he could trust; someone he could count on.

‘June,’ I said brightly, ‘please arrange Thursday to accommodate a three o’clock visit from Mr Donovan.’

‘What about Mr Lexden-Page? You know how he is.’

‘Mr Lexden-Page, June, can be rescheduled.’ Lexden-Page had tripped over a protruding paving-stone and was pursuing the responsible local authority in negligence for (a) damages for pain and suffering in respect of his small toe, and (b) the cost of an extra shoeshine arising from the slight scuff his shoe had received. Lexden-Page could wait.

I returned to my desk and rested the back of my head on the pillow my hands made. What could Donovan want? I asked myself. Then I thought about something completely different, if at all.

The morning of that Thursday saw me relaxed and confident. I wore an attractive blue shirt and my best pure wool suit. Although my desk was an iron one and my carpet was worn down by the chair-legs, it struck me that my office was not unprestigious. It was spacious and it enjoyed a fine view. Looking around it with a freshened eye, I felt a little pang of pride: there were more inconsequential stations in life than the one I occupied. With this office and with customers like Donovan, you had to admit that I was not doing that badly.

But I grew jumpy as three o’clock drew nearer and nearer. Drinking coffee after coffee, I watched the office clock show fifteen-hundred, then fifteen-ten, then fifteen-twenty-five. When, at a quarter to four, I returned from a visit to the lavatory, there it was, Donovan’s silhouette against the window.

‘Hallo,’ Donovan said, standing up with a smile. ‘Sorry I’m late. I want you to have a look at this.’ He reached into a slim briefcase and handed me a sheaf of papers. ‘It came two weeks ago.’ Then he sat down.

I moved into the room. It was as though the last decade had never happened.

I read what he had given me. It was a Petition for divorce. The Petitioner was Arabella Donovan.

‘I see,’ I said.

I leafed through the documents for a second time. The marriage had broken down irretrievably, alleged Mrs Donovan. The Respondent, Donovan, had behaved in such a way that the Petitioner could not reasonably be expected to live with him.

‘Yes,’ I said.

Then I suggested a cup of coffee and picked up the telephone to speak to June. I could easily have simply raised my voice for some, but that would have been undecorous. ‘Do you still take it black, no sugar?’ I asked.

‘That’s right,’ Donovan said, with a note of something – admiration, I think – in his voice.

June came in with a steaming tray and a splashy, red-mouthed smile. June is a tall black girl who used to long-jump for England when she was eighteen, and when she enters a room with her long, spectacular legs she tends to bring things to a standstill. While she poured the coffee, I took another look at Donovan, who was patiently waiting for his cup to fill. He was sitting with his legs crossed. His green eyes, and the skin around them, appeared rested, and his black, thick hair was positively glossy. His unexceptional, off-the-peg suit hung well on his large frame. What really caught my eye, though, were his hands, folded in his lap. They were in perfect condition. They were like the hands that hold the cigarette packets in the advertisements, manicured yet manly, good hands, hands you felt like shaking – the hands of an airline pilot or a surgeon, someone you could trust with your life.

How well he looked, I thought. And then it came back to me. His calmness. I had forgotten that Donovan was, above all, calm. And it was the best kind of calmness, profound and reassuring – it was a tranquillity, a serenity. Don’t worry, it communicated, everything is in hand. Everything is going according to plan. It also said, implicitly, leave everything to me; leave everything to me and everything will turn out well. It was this stillness that gave Donovan his authority, that subtly turned his suggestions into commands. Even then, as I watched him waiting for his coffee cup to fill, I felt the impulse to yield, to drop the reins.

When June had gone Donovan retrieved the papers from me and pointed to a passage in one of the pages. ‘I’m not experienced in this area, so I’m curious to know how often you come across these kinds of allegations.’ He was referring to the section in the Petition headed Particulars. Here Donovan’s culpable behaviour was particularized and broken down into sub-paragraphs (a), (b) and (c).

I was nervous. I said, ‘I must say, they are not commonplace. But I would not say that they were unusual, either.’

Donovan smiled at me and stood up. He began walking unhurriedly around the room. Hallo, I thought. He never used to pace around. Or did he?

He spoke gently. ‘I intend to contest this petition.’ He paused, indicating the arrival of a different point. ‘In my view there are good prospects of defeating it. My wife will not be able to substantiate her allegations, which in any case are unspecific, arguably to an unacceptable degree.’ He looked at me over his shoulder with his green eyes and resumed his pacing. ‘I think you will agree that the tone and content of the pleading are unconvincing.’

I broke a silence. ‘Yes,’ I said.

He continued slowly striding, and for the first time I noticed the inefficiency of his physical movements. He was not clumsy (this would have not been surprising, given that he was a biggish man), he was simply uneconomical with the way he transported himself. He took irregular steps across the room, he swung his arms by his sides with no particular coordination.

I cleared my throat. ‘I don’t have to tell you what my standard advice to clients is in this situation. Contesting a divorce is an expensive and usually fruitless business. We must try and settle this thing as quietly as possible. The last thing we want is a courtroom confrontation.’

Donovan smiled. ‘Yes, I’m aware of the standard advice.’ He picked up his coffee from my desk and regained his seat. Would it not have been simpler for him to sit down first and then pick up his coffee?

The conference, meanwhile, was becoming untidy. It had an unsatisfactory shapelessness about it. We were making confused advances. It was time to get systematically to grips with the issues, the nitty-gritty. I wanted to go back to what Donovan called the standard procedure in meetings of this kind. There were things I needed to know. I needed to know the history: what had prompted Mrs Donovan’s departure from the family home? How much, if any, truth was there in what she alleged? Were there any incidents which his wife might seek to rely on? What were the main obstacles to reconciliation? Was Mrs Donovan in employment? If so, how much did she earn? I needed to know about the financial arrangements of the parties, about the prospects of reconciliation. I needed to know the facts, all of them, and set them out in a row so that I could understand them. Divorce is an extremely complex area, factually.

So I said, ‘Michael, before we go any further there are certain things you need to tell me about Mrs Donovan – about your wife – so that I am able to advise you properly.’ I took out a pen and a fresh pad and wrote Donovan v. Donovan on the cover. ‘Now, firstly, where is your wife at the moment?’

‘At her mother’s house. James, I would love to go into the details but I’m afraid that I’ve got to rush in a minute or two.’ He looked at his watch. ‘Perhaps we could arrange another con – I’ll get Rodney to ring. In the meantime, I wonder if you could serve this on my wife.’ Donovan dipped into his briefcase and brandished some documents. ‘It’s an Answer to the Petition. I’ve left it in general terms for the time being – simply denying her allegations, not making any counter-allegations of my own. There’s no point in restricting our options by pointing any fingers right now.’

I read the Answer. It was exactly what was needed, and I opened my mouth to say so.

‘As regards reconciliation or settlement,’ Donovan said, ‘I think it would be wise to shy away for a while. My wife is not, I should imagine, in a particularly constructive mood at the moment. I think a low-key approach is called for, at least for the time being. Let them make the running. What I have in mind is this: we are more than willing to talk, but only with a view to reconciliation. Certainly, I will not contemplate settlement on the basis of consenting to the divorce. Apart from that, we play it by ear. Take no initiatives unless instructed.’ Donovan opened his case, replaced some documents, and shut the lid with a dull slam of leather. ‘There’s nothing else, is there?’

‘No,’ I said, standing up, thinking, Yes there is, there’s a lot else.

‘Good. James, you’ve been very helpful.’ Donovan began putting on his coat and scarf.

Feeling that a little bit of small talk might be appropriate at this juncture, I asked, ‘How are you feeling? I hear you’ve been unwell recently.’

‘Have I?’ He buttoned his navy blue coat. ‘Oh, yes – that. Yes, I’m a lot better now, thank you, how about you?’

‘Fine, fine. Couldn’t be better.’

‘Just look at that rain,’ Donovan said.

When Donovan left I walked over to the window and watched him hail a taxi. It was four o’clock and already the headlamps shone from the cars. The sky was brown, the rain brilliant under the street lights and, suddenly, everything had become palpable and atmospheric. This was the thing about Donovan – a brightness followed him around, a clarity, it was as if the man moved with Klieg lights tracked down on him …

Arabella Donovan was a nice name. Arabella Donovan, I said to myself; it was almost a supernatural name, you could call a spangled mermaid Arabella Donovan. That peachy voice on Donovan’s answering machine, that must have been Arabella’s voice. I went back to my desk and looked at her photocopied signature on the Petition. It looked a functional signature to me. The letters were printed clearly and regularly. There was no indulgence about the signature, no squiggles or sequins. It was a little disappointing. It seemed a waste of such a nice name. June – June would have done the name justice with her turquoise ink and her fancy, wavy manuscript.

How on earth had Donovan allowed Arabella to slip through his fingers? And what had made Arabella leave someone as eligible as Donovan? What had happened?

I turned once more to the salient points of the Petition. Paragraph I said that the Donovans had married on 5 July 1981. Paragraph 4 said that there were no children born to the Petitioner during the said marriage or at any time. Paragraph 6 revealed that the Petitioner had quit the marital home on 14 July 1988, and at Paragraph 8 it was alleged that Donovan had behaved in such a way that Arabella could not reasonably be expected to live with him. Then I looked again at the Particulars of this allegation.

The Respondent has throughout the marriage treated the Petitioner cruelly and/or unreasonably by inter alia

(a) persistently degrading the Petitioner by his conduct so as to make her feel worthless and/or by

(b) injuriously neglecting the Petitioner by according unreasonable priority to other matters inter alia his occupation and/or by taking no or no sufficient interest in the Petitioner’s welfare and/or by

(c) persistently maintaining prolonged and unreasonable absences from the marital home.

I had my doubts about the logic of the pleading and the vague language it employed, but I could guess at the gist of Arabella’s complaint. Donovan, she said, was a cruel and neglectful husband. That was what it boiled down to.

I regained my seat. On balance, Donovan was right to feel he had a case. The pleadings did not specify the form of the degradation from which Arabella was supposed to have suffered, nor (apart from the matter of the excessive hours he put into his work) were examples given of any maltreatment. Allowing for the customary emotive exaggeration of Petitions, no tangible or damaging misconduct was immediately revealed. There was no suggestion of infidelity or physical violence or of something you could get your hands on, like alcohol or drug abuse, and there was generally an unconvincing amount of huffing and puffing in the pleading; in general, the tactic is to make your case as precise, and therefore as strong, as possible, thereby strengthening your hand for out-of-court negotiations. In this case, the only thing revealed was that Donovan had devoted too much time to his work, hardly the most malevolent of transgressions.

But that was where my understanding screeched to a halt. I rely on information, not intuition. Ferreting out facts from clients, a matter of technique and persistence, I am usually good at. Dates, events, examples, these are things I happily manage. In this case, however, I hardly knew any facts at all. Donovan had disallowed my interrogations, and I was forced to fall back on guesswork: and when it came to sensing the unsaid, to divining what lay beneath the surface, I was weak. I am not, it must be said, greatly interested by those parts of a personality known as the depths. I am happy to take people at face value, with the result that sensitivity to concealed thoughts and emotions is not my strong point. I am a magpie in this respect, drawn towards trinkets and sparklers – more attracted to a person’s superficies, with its gaudy bijouterie of individual traits, than to his or her ‘deeper’ self. Underneath the make-up and knick-knacks, I must confess, I tend to find people wearisome and monotonous, burdened as they are with the same luggage of troubles. And as a solicitor, of course, faced as I am every day with personal problems, I must keep a certain distance. It would not do to become involved.

Going back to that rainy, brown-skied dusk, I stood up and switched on another light to combat the entering darkness. Doubts began to beset me. My situation was not ideal. Donovan was a personal acquaintance and this might cloud my judgment and hamper my conduct of the case. Should I not advise him to seek another solicitor? Moreover, things were rolling along just fine at work. I was busy but not too busy. Donovan would be a demanding client, and the time I would spend thinking about the case would not, I knew, be translated into efficient profits. Was it necessary for me to involve myself?

Of course, even as I asked myself these questions I knew that there was no question about it. It is ridiculous, I know, and shameful, but I was flattered by his attentions. His proximity elevated and enlivened me. This was, of course, a weakness on my part – but what can I say? Faced with Donovan, my normal instincts went haywire. Like one of those Turkish beach turtles that mistake the glow of cafeterias for the luminous sea, I was completely disoriented by him.

FIVE (#ulink_8be99001-9183-5d4a-8b24-f176f1daa9db)

After that, I did not see Donovan for a while. He was back at work. This meant it was just about impossible to contact him, which was inconvenient for me. I had Arabella’s solicitor, a rather abrupt man from the firm of Duggan & Turnbull called Philip Hughes, breathing down my neck. He had rung several times to make tentative approaches, and each time, in accordance with my instructions, I refused his advances. He was becoming impatient. On 31 October 1988, he telephoned me again.

‘Mr Hughes, as I’ve said, I’m afraid I am unable to discuss any questions of settlement. I have had no instructions in that connection from Mr Donovan.’

‘Well, I suggest you get some instructions,’ Hughes said. ‘Pick up the phone and get some instructions.’

‘I can’t do that, I’m afraid. Mr Donovan is abroad at the moment and I have no way of getting in touch with him. He’s a very busy man,’ I said. ‘He travels all the time. He could be anywhere.’

Philip Hughes sounded exasperated. ‘Frankly, I don’t care if he’s in Timbuctoo. Just leave him a message. Tell him,’ he said in different tone of voice, ‘I have a proposition that may interest him.’

I said nothing.

Philip Hughes said carefully, ‘Why don’t I just tell you what we have in mind? What could be lost by that?’

‘I doubt very much that any proposition for settlement would interest Mr Donovan if it involved him accepting the dissolution of his marriage.’

‘You’re certain about that?’

‘Mr Donovan does not believe that his marriage has irretrievably broken down. He thinks that his marriage could be saved.’

Philip Hughes changed the tone of his voice again. This time he spoke in a man-to-man, off-the-record, you-know-it-makes-sense tone of voice. ‘Mr Jones,’ he said. ‘Look. Let’s be sensible. There is no way – and, let me be absolutely clear, by that I mean no way – that Mrs Donovan will go back to Mr Donovan. Frankly, she’s had enough. As far as she is concerned, her marriage is dead and buried. She never wants to lay eyes on her husband again. That is a fact that won’t go away. I know it, now you know it.’ Philip Hughes drew breath. ‘The point is, I would also like Mr Donovan to know it. I want you to make it plain to him that there will be no second bite of the cherry. Frankly, it’s finito la musica. It’s over between him and his wife.’

I could see how Hughes was thinking: I’ve got Donovan all worked out, he was saying to himself. At the moment he’s having difficulty in accepting what is happening to him. He’s denying reality, and that’s understandable, even inevitable – after all, he’s a human being, it’s a normal reaction to a major blow. But, Hughes was thinking, Donovan’s also a lawyer. He’s a reasonable man. Once the truth – that Arabella was gone for ever – sinks in, he’ll quickly see that further resistance would be irrational, that at best it would achieve nothing but a painful and expensive delay of the inevitable. Once he realizes he’s surrounded, he’ll strike a bargain and come out with his hands up in the air. The key, Hughes was saying to himself, was to get Donovan to appreciate one thing – Arabella wasn’t coming back.

‘Mr Hughes,’ I said, ‘I will tell him that as soon as I am able to. I must say, however, that I have my doubts about whether that will change anything. Mr Donovan’s views are very firmly held.’