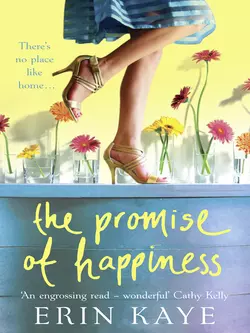

THE PROMISE OF HAPPINESS

Erin Kaye

Join the McNeill family as they attempt to come together to provide the love and support that they all need – whether they know it or not. Perfect for fans of Maeve Binchy and Cathy Kelly.It's a family affair…Louise McNeill arrives home to the idyllic Irish town of Ballyfergus, hoping that it will provide the sanctuary she desperately craves. Starting again with her three-year-old son Oli, Louise's heart is full of apprehension.To make matters worse, Louise's sister Joanne seems far from happy as she watches Louise's little family blossom. But as Joanne grapples with her 'perfect' marriage, is everything as idyllic as it seems?Meanwhile Louise's youngest sister Sian has decided she doesn't want children and wants to dedicate her life to ecological living with husband Andy. But is this a mask to disguise a bigger issue? And is Andy ready to sacrifice parenthood?

Erin Kaye

The Promise of Happiness

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

AVON

A division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street,

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

THE PROMISE OF HAPPINESS. Copyright © Erin Kaye 2011. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

Patricia Gibb asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9781847562012

Ebook Edition © JUNE 2011 ISBN: 9780007340415

Version: 2018-06-26

To Mary Clare, my eldest sister

Contents

Title Page (#uccb8bf72-63fa-56ef-a285-240552052fb7)

Copyright

Chapter One

‘Nearly there, Oli!’ said Louise McNeill brightly to her three-year-old…

Chapter Two

With Joanne’s help it didn’t take Louise long to organise…

Chapter Three

Sian stood on the step at the back of Joanne’s…

Chapter Four

A week later and Louise surveyed the table in front…

Chapter Five

It was early, but the day was already hot and…

Chapter Six

Louise was looking forward to the night out with Joanne,…

Chapter Seven

Sian, who had been awake since dawn, stood looking out…

Chapter Eight

‘Bye, Oli. Mummy’s going to work now,’ said Louise, standing…

Chapter Nine

‘If you don’t hurry up, Holly, I’m going to be…

Chapter Ten

‘So how are things with you, Gemma?’ said Joanne. She…

Chapter Eleven

Andy lay sprawled lifelessly on the sofa, in a T-shirt…

Chapter Twelve

‘She says she doesn’t want to go out,’ said Sian’s…

Chapter Thirteen

Sian stood in the doorway to Louise’s small kitchen wearing…

Chapter Fourteen

On Sunday morning Joanne struggled into the kitchen with the…

Chapter Fifteen

The taxi dropped the girls off and Joanne ran out…

Chapter Sixteen

Sian stared out the shop window decorated with paper snowflakes…

Chapter Seventeen

‘The nurse tells me you’ll get out tomorrow,’ said Andy…

Chapter Eighteen

Sian stood barefoot on the beach at Ballygally, the cool…

Read on for an exclusive reading guide to Promise of Happiness

Reading Group Questions

Read on for an interview with Erin Kaye

In Conversation with Erin Kaye

About the Author

Other Books by Erin Kaye

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One

‘Nearly there, Oli!’ said Louise McNeill brightly to her three-year-old son, Oliver James.

Somewhere in the bowels of the ferry the engine growled and a shudder ran through the ship. Louise put her hand on her belly and her stomach lurched – though not with nausea. She’d spent her youth sailing on these waters – in the sheltered safety of Ballyfergus Lough or, sometimes, venturing out into the choppy waters of the Irish Sea – and not once had she been seasick. And she wasn’t pregnant. No, her nausea was caused by nerves. Louise took a deep breath, glanced at Oli and wondered – panicked suddenly – if she was doing the right thing by coming home.

Oli, restless, banged the fleshy pads of his palms against the sloping window, leaving smudges on it. ‘Now, now,’ said Louise, fretting that he might pick up germs from the glass. Instinctively, she reached out and caught one of his hands in her own. Oli’s olive skin tone came from his father’s side – it certainly hadn’t been inherited from the pale, Celtic-skinned and fair-haired McNeills. She touched a dimple on the back of his hand with her thumb – he was losing his baby fat rapidly, moving on to another stage of development.

Oli was a constant source of fascination to Louise – every new word was an achievement, every task accomplished a source of wonder. Each step along the long, slow road to independence seemed like a miracle. And it was a miracle – rather he was a miracle. Her baby. Hers alone. The child she had thought she would never have. Love and pride swelled in equal measure, threatening to choke her.

‘Are we nearly there yet?’ said Oli, in the high-pitched monotone common among children of his age. Louise found listening to other people’s children grating, but never Oli. He let out a long sigh, having long ago lost interest in the view of the calm, glittering sea, pale blue sky and swooping gulls. Louise put her arm around his waist where he stood on the blue leatherette bench beside her. She pressed her face into the small of his back and inhaled, knowing that if they were ever separated she could recognise him by smell alone.

The boat swung slowly round on its axis and hot July sunshine flooded through the glass. She squinted as the land mass of East Antrim, and the town of Ballyfergus, came slowly into view.

The town was just as Louise had remembered it. The shoreline was dominated by the big working port with its hulking cranes and drab, pre-fabricated buildings. A docked P&O ferry discharged its cargo, an endless stream of lollipop-coloured container lorries, onto the shimmering black asphalt of the quay. Further inland, arcs of slate-roofed white houses, none more than two storeys high, inched up the hills like cake mixture on the side of a bowl. And beyond that the gentle rounded green hills.

‘Look,’ she said and pointed through the window. ‘That’s Ballyfergus. Where Nana and Papa live. That’s where we’re going to live too.’ The idea of this, of bringing Oli home to his grandparents, to be amongst his own, filled her with pleasure. And the feeling of doing something right by her child momentarily displaced the gnawing doubt that she had failed him.

‘Where? Where are we going to live?’ persisted the child. His dark brows came together in a frown and he glared mistrustfully at the lush green hills overlooking Ballyfergus Lough, oblivious, it seemed, to the breathtaking beauty surrounding them.

‘There,’ said Louise pointing at the town, which had served as a port and gateway to the rest of the province for over one thousand years. She remembered that Oli had last visited when he was two and would not recall the trip. ‘See those houses there. Not up on the hill. Down there.’ She pointed at the sprawling cluster of grey and brown buildings on the flat plain. ‘They look really tiny, don’t they?’

Oli nodded.

‘That’s because we’re so far away. We’re going to live in a house down there.’ She pointed roughly in the direction of the indoor swimming pool, a grey block of a building, which sat only metres from the shore.

‘With Nana and Papa?’

‘No, Oli,’ said Louise and he plopped down suddenly onto his bottom. ‘Just you and me. Like always,’ she added, careful to deliver this news in a neutral tone and eradicate any hint of disappointment or anxiety from her voice. She brushed his straight brown fringe, so different from her fine fair hair, off his forehead. He swatted her hand away absent-mindedly.

‘Why?’ said Oli.

‘Oh,’ said Louise, not expecting this question, not here, not now. ‘Well,’ she said carefully and took a deep breath. ‘Because your daddy doesn’t live with us, does he? He lives in Scotland. But of course it might not always be just the two of us. One day Mummy might meet a nice man and …’

Suddenly, Oli slid onto the floor and disappeared under the table. Mischievous brown eyes, the same colour as his father’s, stared up at her. ‘But why can’t we live with Nana and Papa?’

Louise put a hand over her heart and let out a silent sigh of relief. In her zeal to ensure Oli understood, she had yet again answered the question she thought Oli had asked, rather than the one he actually had. It was a fundamental pitfall she’d read about more than once in the library of parenting books that now lay in storage, boxed up in some Edinburgh warehouse.

‘Come on out of there, Oli,’ she said, pulling him gently out from under the table. ‘You don’t know what’s on that floor.’

Louise extracted a bottle of antibacterial gel from her bag. ‘We can’t live with Nana and Papa because they haven’t got enough room for us. Their house is very small.’

But Oli was now more interested in the gel than pursuing this topic of conversation. Louise held his hand by the wrist and squeezed a translucent green blob onto the centre of his palm. ‘This’ll kill all the nasty germs. Now, rub your hands together like this,’ she said, squirting some of the gel onto her own palm and rubbing her hands briskly together.

Oli held his hand inches from his face, stared at the gel and said, ‘It’s got bubbles in it, Mummy.’

‘Yes, I know, darling.’

‘Why?’

‘It just has.’

He extended his hand towards her face, his chubby fingers spread like the fat arms of the starfish that Cameron, her former husband, had once fished out of Tayvallich Bay on the west coast of Scotland. Together they’d knelt on the pebbly beach and wondered at its pale lilac beauty, heads bent together like children. Oli smeared a blob of gel, wet and surprisingly cold, on Louise’s nose. She blinked, surprised, and he let out a squeal of delight.

She laughed then, coming back to the moment, to her perfect boy, and he said, ‘I love you, Mummy.’

She swallowed, fought back the tears of joy. ‘I love you too, my sweet angel.’ She beamed at him and added, ‘Now, hurry up. It goes runny if you don’t do it quickly.’

‘Okay, Mummy.’ Oli slapped his hands together, sending splatters across the Formica table. He let out a cry and looked up at her, slightly shocked-looking, for reassurance.

Louise smiled. ‘That’s it. Now rub them together,’ she said and Oli complied.

She loved the unquestioning trust her son placed in her. She was the epicentre of his world, his everything. And he was hers – she craved his neediness and the fulfilment it gave her as a mother. And for the last three years – no, from the moment of his conception – he had been her obsession.

Her decision to relocate from Edinburgh to Ballyfergus had been taken entirely with Oli’s welfare at the forefront of her mind. Though it was also true that, after many years in Edinburgh, she now primarily associated the city with disappointment and heartache. She had been glad to leave. Her only regret was leaving her best friend, Cindy, behind. But this, she told herself bravely, was a new chapter for her and Oli, though coming back to the town of her birth induced an odd feeling. It was a fresh start but it also felt like she was returning to an old, familiar life. A life she had carelessly left behind as an eighteen-year-old without so much as a backwards glance.

A voice over the tannoy told them to return to their car and Louise gathered up their possessions – colouring books and crayons, books, snacks, a copy of Marie Claire magazine (an optimistic purchase from the shop on the ferry) and her mobile phone. She stuffed them into the stylish, capacious patent leather bag that had become her constant companion since Oli’s birth. Not that she cared much for fashion – not any more. She liked to look her best, of course, and she had not, like some other mums she knew, let herself ‘go’.

Louise descended the first lethal flight down to the car deck, gripping Oli’s hand like a vice. Twice he slipped on the steep metal steps and she hauled him back to his feet. Her left shoulder ached with the weight of the bag and her heartbeat accelerated, her brow beaded with sweat. Her stomach flipped with nerves and excitement. She squeezed Oli’s hand even tighter. He glanced up at her.

‘Watch where you’re going, pet!’ she said, as his foot slipped again and he almost landed on his bottom on the ribbed metal floor at the foot of the stairs. Doors led off from this landing to the top level car deck.

A portly middle-aged man, a member of the ship’s crew, stood on the landing dressed in a short-sleeved pale blue shirt and navy polyester trousers with a perma-press crease down the front of each leg. ‘Do you want a hand, love?’ he said, in the hard-edged, down-to-earth accent of North-East Antrim, and stepped forward with one hand outstretched. ‘If you carry the wee man, I’ll help with your bag.’

‘No, thanks. I’m fine,’ bristled Louise automatically. She missed no opportunity to demonstrate to the world in general that she could cope alone. ‘I can manage.’

The pleasant smile fell from the man’s face. He said nothing more, stepped back and adopted his guard-like stance once again, hands behind his back, and nodded in a tight-lipped manner to the person behind Louise. Realising how rude she had sounded, Louise ducked her head and proceeded quickly to the top of the next flight of stairs, her face flaming with embarrassment.

She told herself she was tired and emotional. The drive across Scotland to the port of Cairnryan had taken the best part of four hours, including a stop for lunch. And she’d not slept well the night before, her sleep disturbed by dreams of Cameron. In the dream she was following him in a storm along a narrow cliff pathway on the southern side of the Firth of Forth – a path they had once walked together in happier times. He wore a bright red jacket, his dark hair plastered to his scalp by the driving rain, his face dripping with water. It was high tide and she could hear the ferocious crash of waves on the treacherous rocks below. She stopped and called out to him that it was too dangerous, that they should turn back. And then, right at that moment, without any warning at all, the coastal path crumbled and Cameron plunged over the edge of the cliff, lost to her forever.

They had been divorced for three years – she had not seen him in as long. Why was she still haunted by dreams of him? Perhaps it was understandable – after living with someone for fifteen years you couldn’t expunge all the memories of your life together from your consciousness. And she didn’t want to. For some of the happiest times of her life had been spent with Cameron. She had given up so much in leaving him. It had taken such courage. And such bravery to build the independent life she now enjoyed.

Why was she thinking of him now, on this day? Annoyed with herself, she tossed her head, shaking off thoughts of him like raindrops, and brought her analysis to bear on the present.

‘There you go again,’ she mumbled under her breath as she and Oli picked their way carefully down the next flight of narrow metal steps into the gloomy bowels of the great ship, ‘pushing people away to prove your independence.’ She hadn’t always been like this – only since Oli. She wanted to run back up the steps and apologise to the man but it was too late. Instead she resolved to stop interpreting kindly offers of help as assaults on her independence.

‘Not long now, honey!’ she said, doing up Oli’s seatbelt. She jumped into the driver’s seat, clapped her hands together and rolled her shoulders in an attempt to ease some of the tension that had built up between her shoulder blades. She imagined her parents, and her older sister Joanne and her three children, all squeezed into the modest home on Churchill Road watching and waiting eagerly for their arrival. It was going to be all right, she told herself.

Once she’d negotiated the tricky ferry ramp, she set off along Coastguard Road, the old route into Ballyfergus, avoiding the harbour bypass. She passed landmarks as familiar as the back of her hands.

‘Look,’ she cried, slowing the car down to a crawl, and staring out the passenger window at a nineteen-sixties concrete block fronted by a big, unimaginative rectangle of dusty tarmac. ‘That’s where I went to school, Oli. That’s where you’ll go to school too when you’re a big boy.’ In the rear-view mirror she saw Oli straining for a better view, his eyes wide with curiosity.

A car behind tooted. She waved good-naturedly and accelerated away. ‘And look, there’s the fish and chip shop,’ she said, as they passed a cluster of small businesses on Upper Cross Street. But on closer inspection she saw that the fish and chip shop was gone, replaced by a plumbing suppliers. ‘Oh, it’s not there any more. But look, there’s the library. I used to go there every week with my mum, and we will too, Oli. Would you like that?’ She kept up this bright trail of chatter, seeking out familiar, reassuring places and noticing changes too, changes that reminded her how Ballyfergus had moved on.

Then, at last, she turned into Churchill Road, where children played in the blazing sun just as she had done as a child. Her hands began to tremble and the perspiration on the palms of her hands made it difficult to grasp the steering wheel. She pulled up outside her parents’ semi-detached house and took a deep breath to calm herself. She smiled to reassure Oli, who was looking at her with his thumb stuck in his mouth, then cut the engine. She stepped out of the car into the sunshine and a warm westerly breeze rolling off the Sallagh Braes, a ring of dramatic rounded cliffs overlooking Ballyfergus. Today the hills were framed by a cloudless cobalt sky, the brilliant shades of green softened by a heat haze rising from the black tarmac.

Louise tucked a stray strand of hair behind her ear and remembered the first time she’d brought Cameron home and they’d parked in the very same spot. He’d been driving then – he always did. He’d looked at the modest house and said, ‘Is this it then?’ and she’d felt herself blush, embarrassed for the first time by her humble origins.

Cameron had been to Watson’s, a private school in Edinburgh and studied English Literature at Edinburgh University. Although only a few years older than Louise he had lived in Paris for a year and spoke fluent French. He seemed so sophisticated and experienced. His worldliness contrasted with her sheltered, mundane upbringing. She realised she had so much to learn about everything and she was his willing pupil. The tone of their relationship was set from the outset. He was the leader, the decision maker – she was the follower, happily compliant. She allowed him to educate her, coach her, mould her. She had told him once that she would follow him to the ends of the earth and she’d meant it.

And here she was all these years later, back it seemed, to where she had started.

Joanne ran out of the house and Louise took a few steps towards her. They briefly embraced and cried, ‘Look at you!’ in unison.

Joanne gave an impression of girlishness despite her forty-five years with her tight-waisted, delicate frame and long wavy blonde locks. The illusion was further reinforced by a knee-length floral printed dress, flat ballerina pumps and a cropped cerise cotton cardigan.

Joanne’s olive-green eyes gleamed with emotion. ‘Welcome home!’ she cried and they hugged again. Louise put her hand on Joanne’s back and was surprised to feel a hard and bony frame under the thin layers of clothing. She realised now how much weight her sister had lost.

‘It’s good to be back,’ she choked, her eyes filling up.

And then the neat, small figure of their mother appeared at the doorway to the house, her hand raised feebly in greeting. And behind her was their dad, with his hand on their mother’s right shoulder. Quite unexpectedly, and uncharacteristically, Louise couldn’t control her tears.

Later, after they’d eaten a lasagne made by Joanne, and Oli was happily watching TV in the little room at the back of the house with his cousins, the women – Louise, Joanne and their mother – sat in the lounge, around the coffee table, chatting. Louise’s dad was in the kitchen with Frankie Cahoon, a neighbour from two doors down, drinking whiskey and talking about their days in the GEC factory. Louise looked down at the dainty china cup and saucer balanced precariously on her knee. It was her mother’s best china – a wedding present from her parents – adorned with delicate red roses and rimmed in gold leaf. If only her cosmopolitan friends could see her now, thought Louise, with a deliciously wry sense of humour.

‘What are you smiling at?’ said Christine McNeill, pale blue eyes, the colour of washed denim, staring at her daughter from behind steel-rimmed glasses. At seventy-three, she had lost none of her perceptiveness. Her gnarled hands rested on the arms of an upright Parker Knoll chair.

‘Oh, I was just thinking how the house hasn’t changed at all,’ said Louise, casting her gaze around the cluttered room. The big flowery paper pressed in on every side, so loud it almost screamed, and the nineteen-fifties walnut cabinet was stuffed to bursting with all manner of trinkets and old-fashioned ornaments.

Her mother followed her gaze and said, a little defensively, ‘Well, I like it. I don’t like all this modern design. Bare walls and hardly any furniture. I like a place to feel homely.’ Her nod was like a full stop at the end of a sentence. ‘Now, would you like some tea?’ Without waiting for an answer she leant forward and gripped the handle of the china teapot with her right hand.

‘Why don’t you let me—’ began Joanne.

‘Ouch!’ cried her mother and she let go of the pot immediately. It wobbled uncertainly for a few moments. A little spurt of brown liquid slopped onto the pristine tray cloth and spread like a bloodstain.

‘Did you burn yourself?’ cried Louise, already out of her seat and by her mother’s side.

‘It’s her arthritis,’ said Joanne flatly.

‘It’s all right,’ said Christine, and she held her hand protectively to her chest. ‘It’ll pass in a minute.’

Joanne sighed loudly. ‘I wish you wouldn’t do that. You know you can’t lift heavy things.’

Louise sat down again and Joanne poured the tea.

‘A teapot isn’t heavy,’ said Christine, glaring at the pot, her lips pressed together in a thin line.

‘It’s too heavy for you. You know that.’ Joanne sounded cross and harsh. She passed round the milk.

‘Joanne,’ said Louise warningly and glared at her sister.

‘What?’ Joanne’s eyes flashed defiantly. She set the milk jug down on the tray, avoiding eye contact.

‘Don’t …’ Louise lowered her voice. ‘Don’t talk to Mum like that.’

‘She’s only got herself to blame.’

‘What? For her arthritis?’

‘No, of course not. But she’s always doing things the doctor’s told her she mustn’t.’

Their mother blinked and said, as though she’d not heard this last exchange, ‘It’s so frustrating not being able to do all the things I used to take for granted.’ She looked at her hand, the thumb joint red and swollen, and suddenly Louise was struck by how much her mother had aged since she’d last seen her. Now that she looked more closely she noticed how grey her mother’s hair had become and how lined her face was. Sitting perched on the chair she seemed shrunken somehow, as though she was slowly disappearing.

‘I know, Mum,’ said Joanne, her voice softening. ‘But it’s best not to try. You only end up hurting yourself.’

Louise swallowed the shock like a dry, hard crust. Up until now she had clung to an image of her mother as she had always been – capable, reserved, self-effacing. The constant, steady backdrop to a happy childhood. Louise remembered sleeves rolled up on wash day revealing taut arms stronger than they appeared; slender pink hands, slimy with sudsy water, hauling clothes out of the twin tub, the water grey from previous washes. She remembered a slim, resolute woman who moved through her narrow life with purpose and busyness, ever watchful for extravagant waste and moral laxness.

She recalled the relentless, tight-fisted management of household finances so that there was always just enough money for Christmas and a week-long summer holiday in a grotty boarding house in Ballycastle. And the going without on her mother’s part that this rigorous budgeting required.

Her mother shifted in her seat, and winced. She flexed the fingers on her right hand and looked at the deformed knuckles with a scowl on her face. ‘The doctor’s put me on a new drug but he says it’ll take weeks, months even, before I notice any difference. Maybe I need another one of those injections …’

‘I’m sorry, Mum,’ said Louise, feeling a sudden rush of compassion for her mother – and a creeping sense of guilt. Balancing the cup and saucer on her knee, she reached over and patted her mother’s knee. ‘I’ll be able to help out more now.’ Why hadn’t Joanne, or Sian, warned her that her mother’s health had deteriorated so?

Thinking of their younger sister, Louise said, ‘Where’s Sian and Andy tonight?’

Joanne replied, ‘Oh, she and Andy had to go to some meeting about that eco-development at Loughanlea.’ Joanne fiddled with the tiny shell buttons on her cardigan, her small feet neatly tucked together under her knees. She seemed restless, on edge and she radiated what Louise could only describe as ill-will. ‘As Chair of Friends of Ballyfergus Lough, Sian said it was really important that she was there for tonight’s meeting,’ she went on, and then added rather formally, ‘She sends her apologies.’

‘That’s okay. I’ll see her tomorrow.’ Louise held her breath while her mother shakily lifted the cup to her lips, its dainty handle sandwiched awkwardly between her forefinger and swollen thumb. She managed to take a sip and return the cup to its place on the saucer without a spillage. Louise relaxed while Joanne, still on edge, let out air like steam.

‘She ought to have been here to welcome you. But you know Sian. Saving the world comes before her own family.’

‘Oh, Joanne,’ said Louise, scolding gently, ‘I’m sure she would’ve been here if she could. And I don’t mind. It’s better for Oli this way. Meeting too many people all at once would just overwhelm him.’

Joanne raised her eyebrows and looked out the window, unconvinced. Louise, wanting to avoid further discord, ploughed on with a change of subject, ‘Anyway, how’s the redevelopment of the old quarry at Loughanlea coming on? It must be nearly finished.’ The disused cement works, located just a few miles outside Ballyfergus on the western shore of the Lough, had blighted the landscape for over two hundred years. Four years ago ambitious plans for its regeneration had finally received the green light from the authorities.

‘According to Sian,’ said Joanne, ‘most of the major construction work’s completed. As well as the mountain bike centre, they’re building a scuba diving centre, a bird watching centre, a heritage railway centre and God knows what all else. And when it’s finished, the eco-village will have over four hundred homes. It’ll cover the northern part of the peninsula.’ She was referring to a wing-shaped spit of land formed from basalt excavated from the quarry and dumped into the Lough.

‘And when’s Sian and Andy’s house going to be ready?’

‘September, I think. Theirs is going to be one of the first to be completed.’

Louise nodded thoughtfully. She’d been so wrapped up in her own plans she’d almost forgotten that Sian was about to move home too, albeit not halfway across the UK.

Her mother tutted loudly, shook her head and set the cup and saucer down noisily on the table. ‘I don’t know what Sian’s thinking about, buying a house with a man she’s not even married to. Don’t get me wrong, your father and I are very fond of Andy.’ She folded her arms across her chest. ‘But we don’t approve of this living together business.’

Louise rolled her eyes at Joanne who said, ‘Everyone lives together before getting married nowadays, Mum.’

‘You didn’t,’ she snapped.

Joanne thought for a moment. ‘Well, maybe I should have. You can’t really know someone until you live with them.’

‘And a fat lot of good it did me,’ said Louise, looking into her cup. She sighed, took a sip of tea and added, ‘Mind you, I imagine an eco-village, whatever that is, will be right up Sian and Andy’s street.’

‘Oh, you should hear the two of them banging on about it,’ said Joanne, diving back into the conversation with sudden energy. ‘They’re like religious zealots. What they don’t know about sustainable living isn’t worth knowing.’

‘They’re always on at your dad and I to grow our own food,’ interjected her mother, nodding, ‘and make compost out of our used tea bags.’ She snorted. ‘I think they forget that your father and I are in our seventies.’

Her mother’s uncharacteristic ridicule took Louise slightly by surprise. ‘Well, the whole project sounds very exciting,’ she said feebly, feeling a little guilty at her participation in the mean-spirited mockery, albeit gentle, of Sian and her fiancé. ‘And it’s good that Sian and Andy are involved. You need passionate people to get something like that off the ground.’

Joanne pulled the edges of her cardigan together. ‘Hmm … I’m just glad she found someone like Andy who shares her views, that’s all.’ But she said it like she was affronted, rather than pleased.

‘Andy’s lovely,’ said Louise. ‘He really is.’

Her mother nodded. ‘Yes, he is a decent fella.’ A pause. ‘In spite of his … ideas.’

‘Well,’ said Louise, ‘there’s nothing wrong with being concerned about the environment.’

Joanne snorted dismissively like Louise didn’t know what she was talking about. She folded her legs and said, snippily, ‘It’s not what they do that bothers me. It’s going round telling the rest of us how to live that grates. It drives Phil nuts.’

Joanne had been married to handsome Phil Montgomery for fifteen years. A little flash of envy pricked Louise. She wished she had a husband and everything that went with it – the sharing of worry and responsibility, the freedom to have as many kids as they pleased, the security of two incomes, the social inclusion. But envy was a destructive emotion – she tried to put these thoughts out of her mind.

‘Wait till Sian starts on you,’ said Joanne, raising her eyebrows and running the flat of her palm down a smooth tanned leg. ‘You’ll know all about it then.’ She stood up suddenly, while Louise was still formulating a reply and slung her bag over her shoulder. ‘Well, I suppose I’d better take my lot home and give you a chance to get Oli to bed. Oh, how could I forget? The keys to your flat!’ She pulled a yellow plastic key fob from the bag and passed it to Louise. ‘It was the best one I could find. Furnished flats are a bit thin on the ground in Ballyfergus.’

‘Thanks.’ Louise nodded, staring at the two shiny Yale keys, the passport to her new life, and rubbed one of them between her finger and thumb. ‘You know it’s really weird moving in somewhere I haven’t seen, even if it is only rented. The pictures on the internet looked nice.’

‘I think you’ll like it,’ said Joanne and frowned. ‘Though it’s not as big as you’re used to.’

‘I’m sure it’ll be just fine. Thanks for sorting it out for me.’

‘Now’s the time to buy, you know,’ said Joanne, dusting something imaginary off the front of her cardigan.

‘And I will,’ said Louise, ‘just as soon as I get my place in Edinburgh sold.’

‘Are you moving in straight away?’ said Mum.

‘Tomorrow. The removal van’s due at eight-thirty but most of my stuff’s staying in storage until I buy a place.’

‘I’ll meet you there at nine to give you a hand,’ said Joanne. ‘Phil can look after the girls for a change!’ She laughed humourlessly, then marched purposefully out of the room. Moments later howls of protest echoed up the hall.

Her father’s voice bellowed from the kitchen, not sounding nearly as scary as he intended. ‘Will you wee ’ans keep the noise down in there? We’re trying to talk.’

‘I’d better go and see what your dad’s up to,’ said her mother, hauling herself to a standing position and hobbling painfully out of the room.

Louise went and stood at the door to the TV room which seemed so much smaller than she remembered it. She slipped her hands into the back pockets of her jeans, and leant against the door frame. The two younger children – seven-year-old Abbey and Oli – were seated cross-legged on the floor in front of the TV. Abbey wore a grubby candy pink T-shirt and mismatched fuchsia-coloured shorts. She insisted on choosing her outfits herself – and it showed. Ten-year-old Holly, thin-faced, with long brown hair and pale blue eyes, was draped over the sofa.

Maddy, womanly at fourteen, was perched on the arm of the sofa, texting furiously with the thumbs of both hands. She possessed a full chest, brown eyes and shoulder-length, dark brown hair streaked with blonde. She wore a short denim skirt over bare orange-brown legs and, even though it was summer and warm outside, a pair of fake Ugg boots. A fringed black and white Palestine scarf was draped around her neck – a fashion, rather than a political, statement.

‘I said it’s time to go,’ said Joanne, authoritatively. She picked up the remote, switched the TV off and threw the control on the sofa with some force. Instantly the air was thick with tension. Holly glanced at Maddy. Louise bit her lip, sensing a confrontation, afraid to watch, afraid to look away. Abbey leapt instantly to her feet, placed her hands on the place where she would one day have hips and stared at her mother, her face hard with anger.

‘Put it back on! I hadn’t finished watching,’ she demanded. Blonde hair, tied up in two pigtails, stuck out either side of her head. Her freckled cheeks were pink with indignation and her entire body shook with rage. Oli’s cherubic mouth fell open in amazement.

The muscles on Joanne’s jaw flexed. ‘I said it was time to go, Abbey.’

‘But you don’t understand. It’s not finished yet, Mum!’ wailed the child, arms held out to convey her frustration at her mother’s ignorance.

Oli stood up, a toy car dangling from his right hand, his mouth still gaping open, utterly transfixed by his cousin.

‘Mum, there’s only a few minutes left to go,’ ventured Maddy, looking up momentarily from her texting. ‘Why don’t you—’

‘That’s enough,’ snapped Joanne, pushing her hair back. ‘I don’t know why you lot can’t just do what you’re asked. Just once.’ Her voice rose to a shriek. ‘Would that be too much to ask? I work my fingers to the bone for this family and I ask you to do one thing. One thing! And you can’t do it.’

Maddy sighed loudly and turned away, her features hidden by a curtain of hair. Joanne put her hands over her face, stood like that for a few moments and then removed them. ‘You can finish watching the programme another day, Abbey,’ she said, her calm voice barely disguising hysteria. She gave Holly a poke in the leg with her finger. ‘Now come on all of you. It’s time to go. Oli needs to go to bed.’

‘It’s not even dark yet,’ said Holly huffily from her slouched position on the sofa, arms folded across her chest. Her skinny legs stretched out Bambi-like from beneath a flowered skirt.

Maddy looked up and said, ‘Holly, can we just, like, go please?’

But Abbey would not give up. ‘It’s not a DVD, Mum!’ she screeched. ‘Don’t you understand? It’s on TV. I’ll never, ever get to see it again. You’re … you’re …’ She bubbled with rage. ‘… so stupid.’

‘Don’t you dare speak to me like that young lady!’ snapped Joanne, and she reached forward and swiped ineffectually at Abbey’s legs – the child, too quick for her mother, sidestepped nimbly out of harm’s way.

Louise bit her lip and winced. Oli ran over to her and peered out from behind her legs, no doubt keen to see, as Louise was, how this fracas would play itself out.

Maddy groaned quietly, rolled her eyes at Louise and returned to her texting. Common wisdom dictated that an only child was harder work than a bigger family, the idea being that an only child, with no sibling to play with, always looked to the parents, or in Louise’s case parent, for entertainment. Louise wasn’t so sure that the theory held. She’d never attempted to hit her child like Joanne had just done. Louise wondered what was going on with her sister. She seemed to be on the verge of losing it.

Abbey looked about feverishly, spied the remote and dived for it, just as Holly scooped it off the couch and clutched it to her chest. ‘Mum said the TV was to stay OFF, Abbey,’ she said sternly, and gave her sister a devilish smirk.

It had the desired effect. Abbey pounced on her sister screaming and both rolled on the couch wrestling with the device.

‘Mum, get her off me!’ yelled Holly. ‘She pulled my hair.’

‘Give me that,’ hollered Abbey, throwing her head back to reveal a face red with exertion and two missing front teeth. ‘Give me that now!’

‘That’s enough both of you!’ screamed Joanne, her eyes bulging with rage, her face puce.

Immediately the children went silent – even Maddy paused in her texting – and stared at their mother. Joanne closed her eyes and sliced the air horizontally with a slow cutting motion, like a conductor silencing the orchestra. She lowered her voice until it was full of menace and barely audible. ‘I have had enough,’ she said, pronouncing each word like an elocution teacher.

Frankie Cahoon shouted a goodbye from the other end of the hall and the front door slammed.

‘What’s going on in here?’ came her father’s genial voice over Louise’s shoulder. He smelled of whiskey and aftershave. What remained of his hair was grey and short and his bald patch, browned by the sun, shone like a polished bowling ball. His jaw was slack with age but his brown eyes twinkled with the same good temper Louise remembered from his youth.

‘World War Three,’ said Louise without humour and she cast a worried glance over her shoulder. Her father chuckled, his whiskery cheeks crumpling into a smile. He rocked a little in his slippers, his hands deep in the pockets of his navy slacks.

‘Let me guess – Abbey?’ he said.

‘Yep.’

‘Grandpa,’ cried Holly, as soon as she saw him. ‘Abbey pulled my—’

‘She wouldn’t let me have the—’ interrupted Abbey.

‘Enough,’ commanded Joanne in a loud, forceful voice and Abbey, now seated on the floor, started to cry.

When it came to tears, their father was a pushover. ‘There, there now, pet,’ he said, shuffling past Louise into the room. He sat on the sofa, pulled the crying child onto his knees and stroked her hair. Abbey’s sobs, instead of abating, intensified.

‘She started it,’ said Joanne, clearly not impressed by this intervention. She folded her arms across her chest and glared at Abbey.

‘Now that’s not very nice, is it, Abbey?’ asked her father and Abbey, glancing furtively at Joanne, sniffed and shook her head.

‘But she wouldn’t give me the remote,’ protested Abbey.

Holly retaliated quickly. ‘She wanted to turn the TV on and Mum said—’

‘I want you both to say sorry to each other,’ said their grandfather, cutting Holly short. After a brief exchange of petulant glares, amazingly, both girls complied. Under their grandfather’s direction, they even embraced and in moments all was forgotten.

Then suddenly Joanne grabbed Abbey by the arm and pulled her off her grandfather’s lap. ‘We’re going now. Come on. Bye, Dad.’ She marched Abbey out of the room brushing past Louise, Maddy and Holly trailing in her wake. ‘You three go on out to the car. I’ll be out in a minute,’ she instructed, giving Abbey a rather forceful shove out the door.

Joanne said a brief goodbye to her parents and Louise followed her out to the car. As soon as the front door closed behind them, Louise said, ‘Are you okay?’

‘Of course I’m okay. Why shouldn’t I be?’

‘It’s just that … well, don’t you think you went a bit over the top in there with the girls?’

‘No,’ said Joanne irritably.

Had Joanne lost all sense of perspective? In Louise’s book, physical punishment was the last resort of out-of-control parents. ‘You tried to hit Abbey, Joanne. And if she hadn’t jumped out of your way, you would have.’

Joanne stopped and turned to face Louise. ‘She deserved it. They all did. They didn’t do what they were asked.’

‘Show me a kid who does?’ said Louise with a laugh, trying to inject some humour into the situation. But her sister remained stony-faced. ‘She’s only seven, Joanne,’ said Louise softly. ‘You have to remember that.’

‘Seven,’ said Joanne, unmoved, ‘is the age of reason. Abbey is old enough to know the difference between right and wrong.’

There was a long pause and, sensing that it would be fruitless to pursue this subject any further, Louise said, ‘Mum and Dad have aged terribly, haven’t they? Mum especially.’

‘Yes, they have,’ sighed Joanne and she rubbed the back of her neck. ‘At least you’ll be able to help out a bit now. It’s been quite a strain on me – what with work and the girls as well. Sian’s only interested in the common good – not helping her own family.’

‘Of course I’ll help out. As for Sian, well, she is working full-time,’ said Louise in her younger sister’s defence.

‘And you think I have more spare time than she does?’ Joanne shook her head. ‘I might work part-time at the pharmacy, Louise, but believe me, running a home and looking after a family as well is more than equivalent to a full-time job. Sian has no idea.’ With that, Joanne got in the car, waved goodbye tersely and drove away.

Later, when Oli had finally fallen asleep, Louise crept up to the bedroom and knelt on the floor and watched him. His chest moved with the gentle rhythm of his breath, his eyelids fluttered in his sleep. Damp curls clung to his sweaty face, and he stirred, throwing a chubby arm up over his head. Louise sat back on her heels and thought about the day’s events. She had done the right thing in coming back, hadn’t she? Oli should know his grandparents and his family. This was the right place for him – and her. And it looked like she had come back at just the right time. For Joanne, it seemed, was barely holding it together.

Chapter Two

With Joanne’s help it didn’t take Louise long to organise the small, two-bedroom flat on Tower Road. Joanne had chosen well. On the first floor in a modern two-storey building, it was bright and functional with pale cream carpet and walls, a brand new blonde wood kitchen and a pristine white bathroom. The bay window in the small, narrow lounge overlooked a pleasant residential street and the flat was only a few minutes’ walk from the seafront. Once Joanne had helped her unpack Oli’s toys, and her own familiar belongings, it started to feel like home.

In Oli’s bedroom, after Joanne had gone, Louise wrestled with a Thomas the Tank duvet cover while Oli played happily with his rediscovered Brio train set.

‘It’s nice here, isn’t it? Do you like it?’ said Louise happily, shaking the cover like a sail in the wind. If everything else went as well as today, their new life would work out just fine.

He shrugged without looking up. ‘It’s okay. Look. Choo-choo. The train’s coming into the station.’ He pushed a red engine along a wooden track. ‘When can we go home?’

The smile fell from her lips. She sank down dejectedly on the tangle of bedcovers and sighed. ‘This is home, Oli. For the time being anyway.’

‘But I want my old room. And I want to see Elliott,’ he said, referring to his best friend at nursery. He stuck out his bottom lip.

‘Oh, darling,’ said Louise, momentarily stuck for the reassuring platitudes that usually sprung so readily to her lips.

He got up then and ran to her and buried his face in her lap. She smoothed the fine soft hairs at the nape of his neck, closed her eyes, and prayed to God that he would settle down.

A few days later, she visited her parents and found her mother in the kitchen drying dishes from the evening meal with a red and white checked tea towel. Mindful of the signs of stress she’d detected in Joanne, Louise was trying to do her bit to support her parents.

She heaved a canvas shopping bag onto the kitchen table. ‘I made a big stew last night,’ she said lifting three foil containers out of the bag and setting them on the table. ‘I thought some would be handy for you and Dad. It’ll do for when you don’t have time to cook.’

Of course this wasn’t true. Her mother had all the time in the world – she was just no longer capable of running a house and putting a square meal on the table every night.

‘Well, thanks, love,’ said her mother, graciously. ‘That is very kind of you.’

‘It’s no bother. I get Oli to help me. It passes the time.’

‘How’s he settling in?’

Louise sighed. ‘He’s been having bad dreams. He’s had me up nearly every night this week.’ She yawned. ‘It’s like having a baby again.’

‘It must be terribly unsettling for him.’

Louise nodded. ‘I’ve tried my best to explain what it means to move house, but I’m not sure how much he understands. He keeps asking me when he can see his friends. I feel awful.’

‘Never mind, love,’ said her mother, with an encouraging smile. ‘He’ll soon make new friends.’

‘Perhaps you’re right,’ said Louise hopefully.

Her mother examined the packages on the table and shook her head. ‘I don’t know where you get the time.’

Louise smiled in acknowledgement. ‘Well, I’m not working and I only have Oli to look after. Not like Joanne.’

She watched her mother dry the bottom of a china dinner plate, then the top. She was so painfully slow. Louise resisted the urge to intervene, placing the portions of stew in the freezer instead. ‘Do you think Joanne’s all right?’ she said casually, closing the freezer door.

‘What do you mean? Like not well?’ Her mother set the plate on the counter and picked up another one.

‘No, she just seems a bit stressed to me.’

Her mother rubbed the tea towel on the surface of the wet plate in a languid circular motion. ‘She probably is. Those girls can be a bit of a handful. And Phil’s not around much to help.’

Louise paused, considering the wisdom of sharing any more of her concerns with her mother. She looked at her gnarled hands, decided against it and said instead, ‘I suppose it’s hard when there’s three of them.’

‘What?’ asked her mother distractedly, stacking the plates.

‘It’s so much easier with just one child.’

‘Easier, maybe,’ her mother replied and left the sentence unfinished – like an old plaster partially hanging off a wound.

‘Go on.’

Her mother sighed, shuffled over to a chair, sat down and regarded Louise thoughtfully. ‘It might be easier for you. But it might not be best for Oli. It’s not healthy him being with just you all the time.’

‘He’s not with me all the time,’ said Louise evenly. ‘He sees other people – adults and kids – regularly. And that’s one of the reasons I moved back, isn’t it? So he could be closer to his family and cousins and grow up knowing them.’

Her mother shrugged her shoulders and Louise found herself compelled to pursue this topic, realising as she spoke that it was essential to her that her mother endorse her lifestyle.

‘Oli has a very happy life, Mum. He wants for nothing.’

‘Except a father.’

Louise bit her lip, anger bubbling up like boiling fudge in a pan. ‘There’s nothing like stating the obvious, is there?’ she said. ‘Why do you have to focus on the one thing he doesn’t have instead of all the things he does? Like a mother who adores him and gave up her job to look after him?’

‘I know just how much you love him, Louise,’ her mother acknowledged, her voice softening. ‘It’s just, well … you know.’

The unsaid words hung between them, fuelling Louise’s anger. A father was the one thing she could not give her son. The only thing. The single, glaring flaw in the almost-perfect life she had so carefully carved out of the wreckage of her marriage. And she tried not to be bitter about the past. She ought to be applauded for what she had done, not derided.

Louise’s chest was so tight, she could hardly breathe. She fought against it for a few moments and managed to say, ‘It’s not how I would have wanted it either, Mum. Not in an ideal world. You know that. But do you have to go rubbing salt into the wound? What I need is support – not people, not my own mother, criticising me.’

Her mother let out a long weary sigh. ‘I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to upset you.’

‘You didn’t mean to upset me?’ cried Louise. ‘That’s a good one.’

Her mother glared at her then, her eyes flinty and full of rare anger. ‘You can’t expect your father and I to approve of something that goes against our values. And people won’t understand.’

‘So that’s what this is about, is it? What other people think? Do you care more about that than your own daughter’s happiness?’

‘No,’ said her mother with a steely gaze. ‘You might not care what people think, Louise. But you ought to. For Oli’s sake. If I was you I wouldn’t go round blabbing your story to people. I’m not sure Ballyfergus is ready to hear it. You don’t want Oli singled out for being different.’

‘He’s no different than any other child from a single-parent family.’

‘Most people don’t set out to be a single parent, Louise.’

Louise took several deep breaths and fought to retain her composure. ‘I know you don’t approve but get over it,’ she hissed. ‘Oli’s here now. Why can’t you just get on with the business of grandmothering him and stop finding fault with us both?’

‘I’d never find fault with Oli,’ said her mother quickly. ‘He’s perfect.’

So the fault lay with Louise, did it? Louise blinked, tried to ignore the tightness in her throat and hold the tears at bay. Why did her mother have to be so judgemental? Why couldn’t she give Louise the unqualified, wholehearted support that she so desperately craved?

Her father padded into the kitchen just then, breaking the tension. He rubbed his hands together briskly. Whiskey had lent his eyes a rheumy quality. ‘Anyone for a wee drink?’

Louise shook her head. ‘Not for me.’ Since she’d had Oli she rarely drank alcohol – and she’d no stomach for it today, not after that horrible, hurtful exchange with her mother.

‘You’ve had quite enough already, Billy,’ said her mother sharply. ‘Why don’t you make us all a cup of tea instead?’ She folded the tea towel and draped it over the radiator to dry.

Her father gave Louise a mournful look and she forced the corners of her mouth up in a smile. He filled the kettle noisily.

Louise glanced at the clock on the wall and said, ‘It’s time I took Oli home. He needs an early night.’

Her father switched the kettle on. ‘Sit down and have a cup of tea. A few more minutes of TV won’t do him any harm.’

Louise whipped her head around and said sharply, ‘What’s he watching at this time of night?’

‘Oh relax, Louise,’ said her father, taking mugs out of the cupboard. ‘It’s one of those children’s channels. It’ll not do him a bit of harm.’

‘I don’t like him watching TV this late. Not just before bedtime. It over-stimulates his brain.’

Her father rolled his eyes. ‘You fuss too much, Louise. Let the child be.’

‘I think I know what’s best for my own son,’ said Louise, tears pricking the back of her eyes. ‘I am his mother after all.’ And with that, she huffed into the TV room, grabbed Oli and stormed out of the house.

‘That smells fantastic. What is it?’ Gemma Mooney lifted the lid on a pot bubbling away on the stove in Joanne’s kitchen on Walnut Grove. She bent her long elegant neck over the pot and peered inside, her chunky metal bracelet clanging against the lid.

‘Black Bean Chilli,’ said Joanne, smiling with satisfaction. She was no match in the looks department for Gemma – with her long legs, angular athletic frame and those bright cat-green eyes – but at least Joanne could cook. While she often joked about Gemma’s domestic incompetency, it made Joanne feel secretly superior to her friend.

‘Hey, Gemma,’ she grinned. ‘What’s in your fridge?’

Gemma shook her head of thick black curls. Not many women could wear their hair as short as she did and get away with it. ‘Oh you know me. A lemon, a few mouldy spuds, some ice and a bottle of wine.’

Joanne laughed and wiped her hands on the front of her apron, acutely aware of her insubstantial, scrawny frame. She loved Gemma to bits but she always felt a little in adequate, a little child-like, in her presence. Still, today she’d made the best of what she had with high heels for extra height, a full skirt to fill out the hips she didn’t possess, and a knitted cardigan to create the illusion of a chest.

‘What about the kids? What do you feed them?’

‘Oh, they’re used to fending for themselves. Roz can rustle up a pretty mean pasta and tomato sauce.’ Gemma replaced the lid on the pot. ‘This’ll be delicious,’ she said and gave Joanne a brief squeeze across the shoulders. ‘Everything you make is. You’re such a good cook. Not like me – I’m hopeless.’

‘You could cook, if you tried,’ said Joanne but she couldn’t resist a satisfied sigh as she looked around the kitchen. The table was laid with plates and dishes of food covered in cling film and cutlery rolled up in napkins. Heidi, the family’s black, two-year-old Flat Coated Retriever, lay on her bed in the corner, watching them with soulful dark amber eyes, her ears flattened against her smooth bullet-shaped head.

Everything, from the home-made vol-au-vents to the fresh strawberry tart, looked good. So why did Joanne still have a niggling sense of dissatisfaction at the back of her mind? Heidi lifted her head and let out a long low heartfelt whine, a protest at being surrounded by food yet not allowed to touch any of it. Roughly, she grabbed the dog’s collar.

‘Here, you’d better go in the utility room or you’ll eat everything like you did last Friday. Did I tell you about that, Gemma? She ate an entire cream cake I’d bought for the kids as a special treat.’

‘Yeah, you told me.’

The dog’s claws scraped the floor as she was dragged away and she whined pathetically as the utility room door shut on her. Turning, Joanne caught a flicker of something in her best friend’s eyes. She felt ashamed for taking out her feelings on the dog. What was wrong with her?

‘Oh, we’ll save the leftovers for her,’ she said brightly.

‘Of course,’ said Gemma smoothly.

Joanne peered wistfully out the patio doors at a dull grey sky. ‘Do you think it’s going to rain? At least the garden’s looking good.’

She’d made the most of the tight space, and the borders, still wet from the last shower, were brimming with summer flowers – pink and white foxgloves, frothy white gypsophila and pale purple lavender.

‘Great in the kitchen – green fingers too. Your husband’s spoiled,’ Gemma said lightly and Joanne’s chest swelled with pride.

She blushed and said, ‘Have I invited too many people? I’d kind of banked on good weather and now, if it rains, everyone’ll have to squeeze inside.’

The house was detached and had four bedrooms but everything about it was compact, a fact that constantly irked, like an itchy label on the back of a sweater. Considering she and Phil both had professional jobs, they really ought to be living in a bigger, better house. But that wasn’t going to happen anytime soon – not with Phil squandering every spare penny … no, she mustn’t go there, not today, not at Louise’s homecoming party.

‘It’ll be fine,’ said Gemma airily, ‘And I’m sure Louise’ll appreciate it.’ She leant against the counter, her skinny black jeans and black boat-necked jersey top emphasising her sexy contours. Joanne, in her pretty, flared skirt and delicate high heels felt suddenly in danger of appearing frumpy in comparison. And once again, she found herself wondering why Gemma was still alone. Surely there must be a man out there for her?

‘Do you think I’ve put on weight?’ said Gemma suddenly, sucking her already flat belly in so that it was concave.

‘Don’t be ridiculous!’ said Joanne loyally. ‘You look fantastic. Like you always do.’

Roz, Gemma’s daughter, popped her head through the kitchen door. ‘Can me and Maddy go down the shop for some magazines?’ It was Roz and Maddy who’d brought Gemma and Joanne together. They’d met at a mother and baby coffee morning when the girls were little.

Gemma looked at Joanne and shrugged her smooth right shoulder indifferently.

‘Why not?’ said Joanne as Maddy followed Roz into the room.

Gemma reached for her purse, found a fiver and handed it to her daughter. Joanne did the same with Maddy adding, as she handed over the money, ‘Just don’t be too long. Everyone’ll be arriving soon.’

The girls, over-made-up and dressed like twins in leggings, ankle boots and baggy tops with a slightly disconcerting eighties look about them, had only just left the room when Abbey came running in, dressed in clothes of her own choosing – red leggings which bagged at the knees and clashed with her orange T-shirt. Her straight, fine hair was carelessly pinned to one side with a diamante barrette with half the stones missing.

‘I want to go to the shop too,’ announced Abbey breathlessly.

Joanne smiled patiently. ‘You can’t, darling. You’re too young.’

‘I’m not too young to go with Maddy and Roz! They can take me, can’t they, Mum? Can’t they, Auntie Gemma?’ she pleaded, the hope in her voice slipping into desperation as the two women exchanged glances. ‘Make them take me, Mum!’

‘No, Abbey. I’m sorry, the answer’s no.’ Joanne paused and then added brightly, ‘Anyway, I need a big girl to help me.’

Abbey folded her arms across her chest defiantly and Joanne pressed on, ‘See all these crisps and nibbles. Can you put them in these bowls for me, please? The rest of our guests will be arriving soon.’

‘That’s not fair. I have to do all the work and they get to go to the shop.’ Abbey glowered. ‘I bet you a million pounds they’re buying sweets.’

‘They are not buying sweets, I can assure you,’ said Joanne, losing patience. She moved towards Abbey, wafting a tea towel at her like a Spanish bullfighter. ‘If you’re not going to help, you can get out of my kitchen. Go on, out!’

‘I’m not helping you ever again,’ shouted Abbey and she ran out of the room and slammed the door behind her.

Both women burst out laughing.

‘Why is Abbey so much work? If only I had a boy, like you, instead of all girls,’ said Joanne. In addition to Roz, Gemma had a twelve-year-old son, Jack.

Gemma raised her eyebrows. ‘Jack has his moments too, you know. But any problems and I just call his dad.’ She sighed. ‘Having said that, Abbey’s the feistiest little girl I’ve ever met. Do you remember that year on holiday in Spain when she was only four and we lost her at the pool?’

‘I’ll never forget it,’ said Joanne, recalling the feeling of heart-stopping panic.

‘And we found her a full twenty minutes later, sitting at the bar drinking orange juice, chatting away to the barman with her handbag on the seat beside her!’

Joanne shook her head, laughing at the memory of her fearless daughter though, at the time, it hadn’t been at all funny.

‘Oh my goodness. Would you look at the time? Gemma, love, you wouldn’t do me a favour would you and put out the nibbles? And I wonder what’s keeping Phil?’ Joanne added. ‘He knows everyone’s due at five.’ She slid on a pair of oven gloves, opened the oven door and waved away a bellow of steam.

Gemma sauntered slowly over to the island unit, ripped open a packet of crisps and ate one.

Peering inside the oven, Joanne said, ‘The chicken’s just about done. I’d better turn it off.’

‘Wasn’t he playing golf today?’ said Gemma, tipping crisps into a ceramic bowl.

Joanne turned the gas off under the chilli. ‘Yes, but he promised me he’d come straight home to give me a hand.’ She stood up and made a sweeping gesture with her left hand around the kitchen. ‘And of course everything’s done and there’s no sign of him. Typical.’

‘He must’ve got held up,’ said Gemma reassuringly. ‘Have you tried calling him on his mobile?’

‘I did. It just tripped to voicemail.’ Joanne took off the oven gloves and placed them on top of the cooker. She shook her head. ‘Sometimes I wonder, Gemma,’ she said and paused.

‘Wonder what?’

‘If life wouldn’t be easier on my own.’

Gemma looked at her sharply. ‘Do you mean that?’

Joanne reddened, her bluff called. ‘No, of course not. That was a stupid thing to say, wasn’t it?’

Gemma said sadly, ‘There’s nothing easy about raising a family on your own.’

‘Oh, of course, I’m sorry, Gemma,’ said Joanne. ‘That was thoughtless of me.’

‘I tell you, what I longed for most after Jimmy left was another adult just being there so that I wasn’t responsible for absolutely everything. I couldn’t even go out for an evening walk around the block without getting a babysitter.’ Gemma paused and looked out the window, then added quite brightly, tipping salt and vinegar crisps into a bowl, ‘Those days are behind me now, of course. They’re both pretty independent and Roz is old enough to mind Jack for a few hours.’

‘And they stay with their dad every Tuesday night and every other weekend,’ Joanne reminded her friend. ‘You know sometimes I envy you those times – when you’ve no children or husband to worry about. When you can do things that you want to do and you don’t have to be accountable to anybody else.’

Gemma gave Joanne a puzzled look and scrunched an empty crisp bag up in her hand. ‘It can be lonely too though, Joanne. And it’s not through choice. I’d love to be happily married like you.’

‘And you will be,’ said Joanne positively. The idea that Gemma envied her sent a little thrill of pleasure through her. She lifted a ripe avocado out of the fruit bowl and pierced the rough, mottled skin with a sharp knife. ‘You just haven’t met the right man yet.’ She didn’t add that, even surrounded by her family, she sometimes felt lonely too. Phil usually played squash on Friday night and then went to the pub with his pals. He regularly disappeared off golfing at lunchtime on a Saturday and sometimes didn’t come home till midnight. She thought she’d married a home-loving man like her father – how wrong she had been …

Just then the mobile phone rang. Joanne wiped her hands quickly on a tea towel and answered it. It was Phil and he sounded drunk. The call was brief and contained no surprises. When it was over, Joanne set the phone down carefully on the counter, the feeling of disappointment as familiar as the simmering rage.

‘Well?’ said Gemma.

‘You know what?’ said Joanne, by way of reply. She did not wait for a response from Gemma. ‘I seem to spend my life being let down by Phil. He’s always promising the earth and never delivers.’

Gemma threw a clutch of crisp bags in the bin and licked the tips of her fingers. ‘Where is he?’

Joanne let out a puff of air and shook her head. ‘Right now he’s in the bar at the golf club. They’ve just ordered food even though he knows there’s food here. He says he’ll be home after that.’

‘Oh,’ said Gemma. She rubbed at an old paint spot on the limestone floor with the tip of her open-toed sandal.

Joanne cut around the middle of the avocado and twisted it to separate the two halves. She prised out the stone, which skittered across the counter. ‘Last week he promised Abbey he’d take her swimming on Sunday morning and he was too hung-over. He forgot about Maddy’s parents’ night at the school in spite of me reminding him three times and sending him a text.’ She paused, held the knife in the air and went on, ‘Two weeks ago we were supposed to be going round to the Dohertys’ for dinner and he came home pissed from the golf club at eight o’clock. You remember that? We had to call it off in the end. I had to pretend I had a migraine. And I really wanted to go.’

‘I know. You got that new dress out of Menary’s specially.’

Joanne viciously diced the avocado flesh and tossed it in a bowl. She lifted a lime from the fruit bowl and held it in the air between her index finger and thumb. ‘And the week before that I opened a red credit card bill he’d not bothered to pay. Do you want me to go on?’

Gemma bit her lip. ‘I get the picture.’

Joanne hacked a lime in two. ‘There’s always something. He’s just so … so irresponsible, Gemma. It’s like having a fourth child these days. No, it’s worse because I’ve absolutely no control over what he does. I never relax. I never know what disaster’s coming next.’

‘Well, you know what I think,’ said Gemma and she raised her eyebrows and gave Joanne a hard stare. She knew all about Phil’s gambling, his drinking, his extravagant spending, his unreliability.

Joanne set the knife down on the chopping board and sighed, her anger spent. ‘I know, I know. I should stop complaining and do something about it.’

‘It’s just that, honestly, Joanne, you should hear yourself,’ said Gemma, sounding a little exasperated. ‘I can’t remember the last time I heard you say a good word about Phil.’

‘That’s because there isn’t a good word to say.’ She held half a lime over the bowl and rammed a wooden reamer into the flesh. Juice squirted out, stinging a nick on the back of her hand.

‘You sound so cynical,’ said Gemma sadly.

Joanne threw the squeezed lime in the bin and rinsed her hands. ‘That’s because I am.’

‘Leave him then.’

Joanne looked out the window and sighed. ‘You know I wouldn’t do that to the children.’ She dried her hands and fixed her friend with a steady stare. Didn’t Gemma realise that she just wanted to let off steam, not be told what to do?

‘Well,’ said Gemma, looking away and speaking slowly, as if choosing her words very carefully. ‘There’s a lot worse things can happen to children than divorce. Living in an unhappy home can be just as damaging.’

‘You didn’t say that when Jimmy left. And I remember it, Gemma. I remember how awful it was for the kids. And for you.’

Gemma folded her arms. She tipped her chin upwards and said, ‘They got over it. We all did. And Jimmy and I get on okay now. I mean we’re civil to each other and we both put the children first.’

Aware she had touched a raw spot, Joanne rushed to bolster Gemma’s confidence. ‘I think you’ve done just great since the divorce, Gemma. I really admire you for how you’ve managed everything. The kids are happy and well-balanced. And I know how hard it was for you when he moved in with Sarah.’

Gemma suddenly smiled brightly. ‘No, it’s all right, really. It was a long time ago.’ She paused and then added, ‘Look, I was just playing devil’s advocate there. You don’t really want to leave Phil – or have him leave you – do you?’

Joanne stared at her open-mouthed. ‘Phil wouldn’t leave me. I—’ She felt her heart begin to race.

‘Oh, Joanne, I’m so sorry. I didn’t mean to panic you. It was just a “for instance” – I was just thinking of me and Jimmy.’

‘I – no, Phil won’t leave me. I keep the house nice, the food …’ She gestured helplessly. ‘I really don’t know what I’d do without him.’ Recovering her composure, she added, ‘Look, I’m sorry to bang on about Phil all the time, especially when I don’t take your advice.’

‘I’m not trying to tell you what to do, Joanne,’ said Gemma looking directly into her eyes. ‘It’s just that I care for you and I want you to be happy.’

Joanne smiled. ‘I know that, love. And I guess I just want someone to listen.’

‘That’s what friends are for.’

Joanne went over and gave Gemma a hug and said, simply, ‘Thanks.’ It fell far short of conveying the gratitude she felt towards Gemma for her friendship and support over the years.

Then the doorbell went and the two women separated.

Joanne straightened her skirt and clapped her hands together. ‘Right, party time!’

Chapter Three

Sian stood on the step at the back of Joanne’s house, holding a glass of wine and looking out at the garden, relieved at being forgiven for being so late. Thankfully Joanne understood that they had to bike all the way from the other side of town – though she and Andy owned an old second-hand car, they rarely used it.

It had been nearly twenty years since she’d visited North Africa in her second year of a Geography degree course at uni and seen first-hand the effects of over-population on a fragile ecosystem – dried-up riverbeds caused by over-farming, starving livestock, ruined crops. She’d seen with her own horrified eyes what poverty looked like – children maimed at birth so they could ‘earn’ a living as beggars, others labouring like ants in a leather tanning factory from dawn till dusk, and stinking, reeking, overcrowded living conditions. She’d come home humbled – and thankful that she’d been born in a first world country where a full belly and medical care were taken for granted. And long before the phrase carbon footprint was coined, she’d devoted her life to minimising her impact on the earth. She fervently believed that, by example, she might persuade others to do the same.

She sipped the wine and looked up at the sky heavy with clouds – so far the rain had held off. The patio doors that led into the lounge were open and behind her an assortment of aunts and uncles and cousins were sitting about chatting and eating. Younger members of the family ran in and out of the room until someone hollered at them to ‘cut it out’. She eyed Joanne’s flowers – one day she’d persuade her to put in veggies too. Everyone had to do their bit. She and Andy were in total agreement on that.

She looked over at Andy, tall and slim and fit, standing on the small square of grass in the centre of the garden. A worn grey T-shirt hung on his well-defined frame and he wore an old pair of shorts over shapely legs, browned from the sun. His short sun-streaked blond hair stood up in messy tufts. She remembered the day she’d first set eyes on him. She’d attended her very first meeting of Friends of Ballyfergus Lough nearly five years ago. And there he was in shorts and a torn T-shirt looking much the same as he did today. She’d fallen in love with him immediately and they’d moved in together within six weeks.

Sian sighed and ran a hand through her tightly cropped fair hair. Not only was he the sexiest man she had ever seen, she loved the languid fluidity of his movements, his relaxed smile, his easygoing nature. In these respects he was the very opposite of her – and maybe that was why their relationship worked. He shared her passion for saving the earth but didn’t take himself, or the cause, quite as seriously as she did. He helped her to maintain perspective and, in the face of near apathy from ninety-nine per cent of the population, retain her sense of humour.

She could still hardly believe this gorgeous sexy man and she were getting married next year. Sometimes she couldn’t believe her good fortune – both her sisters’ marriages confirmed what she suspected. Not everyone found their soulmate. She and Andy were the lucky ones. And together they were invincible. Nothing could come between them, not now, not ever. They shared the same values – they both wanted the same things out of life.

Oli stood just a few metres away from Andy. The child wore clothes that looked like they’d never seen a spot of mud in their life – even his trainers were sparkling white. Sian was filled with dismay. Children should be grubby and messy and muddy, not clean and pristine like they’d just come out of a washing machine. But that was Louise all over. Joanne had proudly shown her the expensive wine and chocolates Louise had brought – whereas she and Andy had contributed organic vegetables from their allotment.

Andy smiled at the boy and the corners of his dark eyes crinkled up, his skin leathery from all the time spent outdoors. His smile was wide and genuine, and his gaze was focused on Oli as though he was the only thing of importance at that moment. Sian understood only too well why clients of the outdoor centre in Cushendall where he worked, loved him. Kids, especially, adored him.

Very gently, Andy tapped a football with the side of his trainer and it came to rest just in front of Oli.

The expression on the toddler’s face as he squared up to kick the ball was fierce – his brows knit together, his tongue protruding slightly from the left side of his mouth. Sian smiled. She had seen that expression of quiet determination before – on her sister Louise’s face. She’d always been single-minded and competitive. He took aim, swung his leg – and missed the ball.

The swinging action made him lose his balance, his foot gave way beneath him on the wet grass and he landed suddenly on his bottom. Unperturbed, he immediately rolled onto his knees and stood up, using his hands to lever himself onto his feet. Sian noted with satisfaction the grass stains on his knees and on the seat of his jeans. Oli wiped his muddy hands down the front of his shirt and Sian smiled.

The little boy stared at the ball wide-eyed and disbelieving as if some sinister trick was at work.

‘You missed the ball,’ called out Andy. ‘It’s okay. Have another go, big man.’

Oli screwed his face up in concentration, took another short run at the ball, swung his leg and this time made contact. The ball skidded across the grass and rolled slowly between Andy’s legs. He made no attempt to stop it.

‘Goal! Goal!’ shouted Oli, punching the air with fisted hands.

Andy cheered and the boy ran to him and Andy scooped him up and swung him around in the air. Then he put him under his right arm, like a package, ruffled his hair with his left and deposited the boy back on the ground.

‘Again! Again!’ he squealed, jumping up and down. Just then Abbey and Holly came hurtling across the garden and threw themselves at Andy. He fell backwards onto the grass and the girls jumped on top of him, screaming with delight. Sian threw her head back and laughed.

‘What’s so funny?’ asked Joanne, coming to stand beside her. She held a half-full bottle of white wine by the neck in her right hand, a wine glass in her left.

‘Oh, it’s Andy and the kids,’ Sian smiled. ‘They’re having a great time. Look at them.’

‘Poor Andy,’ said Joanne with a wry smile as Oli threw himself on top of the heap of legs and arms, squealing with delight.

‘Sure Andy loves it,’ said Sian.

‘He must do,’ said Joanne watching as Andy scrambled to his feet, laughing, the back of his T-shirt soiled with stains. Within seconds he’d organised a two-a-side football game. ‘You know he’s absolutely great with kids. Look at little Oli. He just adores Andy.’

Sian beamed with pride. The children made no secret of the fact that their (almost) Uncle Andy was their favourite male relative.

‘I suppose that’s what Oli’s crying out for,’ Joanne went on. ‘A bit of male rough and tumble.’

‘I guess so,’ said Sian and this innocuous comment seemed to open the floodgates for Joanne.

‘I feel awful saying this,’ she confided, ‘but I think Louise should’ve given more thought to what it would be like for Oli without a dad.’ She leant forward conspiratorially and whispered darkly, ‘I think it’s already affected him, you know.’

‘Surely not!’ said Sian, glancing over at the happy, smiling child. ‘He’s little more than a baby.’

‘Louise spoils him. Did you see his trainers? Dolce and Gabbana. I think she spoils him to make up for the fact that he doesn’t have a father, but money can’t make up for that, can it?’ Joanne tutted her disapproval, which sounded more like jealousy to Sian, and went on, ‘And he’s far too clingy. He sleeps in Louise’s bed every night, you know.’ She nodded her head firmly as if she had just divulged a shocking secret, filled her glass to the brim, topped up Sian’s, and set the empty bottle on the step.

‘What’s so wrong with that? Lots of parents let their kids sleep with them, don’t they?’

Joanne laughed cynically. ‘Only those that don’t have a life.’

‘Well, how she raises Oli is Louise’s business,’ said Sian. ‘What I object to is the fact that she had him in the first place.’

‘Because she’s a single mum?’ said Joanne incredulously. ‘I wouldn’t have put you down for a traditionalist.’

Sian shook her head. ‘I couldn’t care less whether she’s married or not. What I care about is the fact that she had him at all. There are enough kids in the world without adding to the problem.’

Joanne rolled her eyes. ‘Here we go again.’

Anger flared up inside Sian. As a child Joanne had never taken her seriously and she still treated Sian like the younger sister she was, putting her down, dismissing her at every opportunity. But this was a subject about which Sian knew far more than her sister. She would make her listen. ‘The biggest problem facing mankind is over-population. There are too many people competing for scarce resources – land, water, food. And competition ultimately leads to war. Over-population is the primary cause of most of the world’s ills. And it’s forced us to embrace dangerous technologies like nuclear power. No, there are simply too many of us – way too many.’

‘Not in the UK there aren’t,’ argued Joanne. ‘Our problem is a falling birth rate. In a few years’ time there won’t be enough young people to support our ageing population. It’s the people in the third world having ten, twelve babies that are the problem. Not us in the West.’