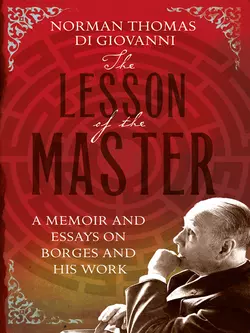

The Lesson of the Master

Norman Thomas di Giovanni

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 191.96 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 28.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A collection of essays on Jorge Luis Borges by his long-time friend and collaborator.Jorge Luis Borges – Argentine poet, essayist, and short-story writer – is widely considered one of the giants of 20th-century world literature.Norman Thomas di Giovanni worked alongside Borges for a number of years creating English translations of his work, the only translations personally overseen by Borges himself. In The Lesson of the Master, a memoir and essays, he writes about his time with Borges but also offers us a unique insight on the man and his work.It is an indispensable volume for Borges readers and his growing legion of students and scholars.