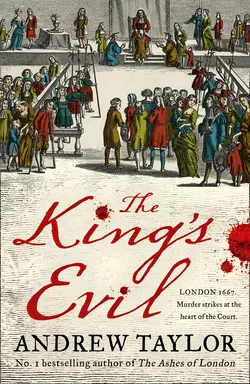

The King’s Evil

Andrew Taylor

From the No.1 bestselling author of The Ashes of London and The Fire Court comes the next book in the phenomenally successful series following James Marwood.A royal scandal that could change the face of England forever… London 1667. In the Court of Charles II, it’s a dangerous time to be alive – a wrong move could lead to disgrace, exile or death. The discovery of a murder at Clarendon House, the palatial home of one of the highest courtiers in the land, could have catastrophic consequences. James Marwood, a traitor’s son, is ordered to cover up the murder. But the dead man is Edward Alderley, the cousin of one of Marwood’s acquaintances. Cat Lovett had every reason to want her cousin dead. Since his murder, she has vanished, and all the evidence points to her as the killer. Marwood is determined to clear Cat’s name and discover who really killed Alderley. But time is running out for everyone. If he makes a mistake, it could threaten not only the government but the King himself…

Copyright (#u564be392-9748-567a-8be7-6d7209f6252a)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers 2019

Copyright © Andrew Taylor 2019

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover illustrations © Heritage Image Partnership Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo (https://www.alamy.com/) and Shutterstock.com (https://www.shutterstock.com/)

Andrew Taylor asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Prelims show image of Clarendon House © Antiqua Print Gallery/Alamy Stock Photo (https://www.alamy.com/)

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008119188

Ebook Edition © April 2019 ISBN: 9780008119171

Version: 2019-02-28

Dedication (#u564be392-9748-567a-8be7-6d7209f6252a)

For Caroline

Epigraph (#u564be392-9748-567a-8be7-6d7209f6252a)

To that soft Charm, that Spell, that Magick Bough,

That high Enchantment I betake me now:

And to that Hand (the Branch of Heavens faire Tree)

I kneele for help: O! lay that hand on me,

Adored Cesar! and my Faith is such,

I shall be heal’d, if that my King but touch.

The Evill is not Yours: my sorrow sings,

Mine is the Evill, but the Cure, the KINGS.

Robert Herrick, ‘To the King, to cure the Evill’

(Hesperides, 1648)

Contents

Cover (#u6df67007-7b64-56fc-9b0d-c7b311cb16c3)

Title Page (#u8b8da022-1ee0-52cc-9cc3-d108f4456bcd)

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

The Main Characters

The Royal Family

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Chapter Forty-Six

Chapter Forty-Seven

Chapter Forty-Eight

Chapter Forty-Nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-One

Chapter Fifty-Two

Chapter Fifty-Three

Chapter Fifty-Four

Chapter Fifty-Five

Chapter Fifty-Six

Chapter Fifty-Seven

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author

By the same Author

About the Publisher

THE MAIN CHARACTERS (#u564be392-9748-567a-8be7-6d7209f6252a)

Infirmary Close, The Savoy

James Marwood, clerk to Joseph Williamson, and to the Board of Red Cloth

Margaret and Sam Witherdine, his servants

The Drawing Office, Henrietta Street

Simon Hakesby, surveyor and architect

‘Jane Hakesby’, his maid, formerly known as Catherine Lovett

Brennan, his draughtsman

Whitehall

King Charles II

James, Duke of York, his brother

Joseph Williamson, Undersecretary of State to Lord Arlington

William Chiffinch, Keeper of the King’s Private Closet

George Villiers, second Duke of Buckingham

John Knight, the King’s Surgeon General

Clarendon House

Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon, the former Lord Chancellor of England

George Milcote, a gentleman of his household

Matthew Gorse, a servant

Others

Olivia, Lady Quincy, formerly Mistress Alderley

Stephen, her footboy

Mr Turner, a lawyer, of Barnard’s Inn

Mr Veal, of London

Roger, his servant

Rev Dr Burbrough, of Cambridge

Rev Richard Warley, of Cambridge

Mistress Warley, his grandmother

Frances, a child

Mr Mangot, of Woor Green

Israel Halmore, a refugee

THE ROYAL FAMILY (#u564be392-9748-567a-8be7-6d7209f6252a)

CHAPTER ONE (#u564be392-9748-567a-8be7-6d7209f6252a)

HE COULD NOT help himself. In one fluid movement, he stepped back, twisting to present his side to the enemy. His right leg was slightly bent at the knee, the foot pointing towards danger. In that instant, he was perfectly poised, as his fencing master had taught him, ready to thrust in tierce, ready to spit the devil before him like a fowl for the roasting.

As he moved, he heard a sharp intake of breath, not his own. His right foot was on solid ground. But the left (‘at right angles to the body, monsieur, for stability and strength’) was floating in the air.

‘God’s—’

In that same instant, he stared at the figure in front of him. Dusk was pouring through the grimy windows of the basement like a noxious vapour. He wanted to beg for help. No words came.

He flung out his arms in front of him in a violent attempt to restore his balance. His fingers stretched, groping for a hand to pull him back. Steel clattered on stone.

He fell with no more choice in the matter than a poleaxed ox. His head slammed against the coping. Pain dazzled him. He cried out. His arms and legs flailed as he fell. The damp, unyielding masonry grazed his fingers.

Nothing to hold. Nothing to—

His shoulder jarred against stone. The water hit him. The wintry chill cancelled all pain and drove the breath from his body. He opened his mouth to cry out, to breathe. The cold flooded his lungs. He choked.

Fiery agonies stabbed his chest. He sank. He had always feared water, had never learned to swim. His hands scraped against unyielding stone. His boots filled, dragging his legs down.

His head broke free. He gulped a mouthful of air. Far above him, he glimpsed the shadowy outline of a head and shoulders.

‘Help me,’ he cried. ‘For the—’

But the words drowned as his body sank again and the water sealed him into its embrace. The purest in London, that’s what her ladyship claimed. His fingernails scrabbled against the stone, trying to prise out the mortar to find handholds. His limbs were leaden. The pain in his chest grew worse and worse. It was impossible that such agony could exist.

Despair paralysed him. Here was an eternity of suffering. Here at last was hell.

The pain retreated. He was no longer cold, but pleasantly warm. Slowly, it seemed, every sensation vanished, leaving behind only a blessed sense of peace.

So this, he thought, this is—

CHAPTER TWO (#u564be392-9748-567a-8be7-6d7209f6252a)

One Day Earlier

ON FRIDAY, I was watching the King healing the sick in the Banqueting House at Whitehall.

‘Don’t look round,’ Lady Quincy said softly.

At the sound of her voice, something twisted in my chest. I had met her last year, in the aftermath of the Great Fire, during an episode of my life I preferred not to dwell on, which had left her a widow. She was a few years older than me, and there was something about her that drew my eyes towards her. Before I could stop myself, I turned my head. She was staring at her gloved hands. Her hat had a wide brim and a veil concealed her face. She was standing beside me. She had brought someone with her, but I could not get a clear view. Someone small, though. A child? A dwarf?

‘Pretend it’s the ceremony that interests you,’ she murmured. ‘Not me. Or I shall have to go.’

We were on the balcony, and the entire sweep of the hall was laid out before us. My eyes went back to the King. In this place, the largest and by far the grandest apartment in the palace of Whitehall, Charles II was seated on his throne below a canopy of state, with the royal arms above, flanked by crowds of courtiers and surpliced clergymen, including his personal confessor, the Clerk of the Closet. His face was calm and very serious. I wondered whether he could ever forget that his father had once stepped through the tall window halfway down the hall on to the scaffold outside, where a masked executioner had been waiting for him with his axe. As a child, I had been in the crowd that had watched as the old king’s head was struck from his body.

‘Say nothing,’ Lady Quincy said. ‘Listen.’

The Yeomen of the Guard marshalled the crowds in the body of the hall, their scarlet uniforms bright among the duller colours worn by most of the sufferers and their attendants. Many of the courtiers held handkerchiefs to their noses, because ill people did not smell agreeable.

‘I’ve a warning,’ she went on. ‘Not for you. For someone we shan’t name.’

I watched the sick. Most of them had visible swellings, great goitres that bulged from their necks or distorted their features. They suffered from scrofula, the disease which blighted so many lives, and which was popularly known as the King’s Evil, because the King’s healing hands had the power to cure it. There were at least two hundred sufferers in the hall below.

‘I had a visitor on Wednesday.’ Lady Quincy’s voice was even softer than before. The hairs lifted on the back of my neck. ‘My stepson, Edward Alderley.’

One of the royal surgeons led them up, one by one, to kneel before the King. Some were lame, hobbling on crutches or carried by their friends. There were men, women and children. There were richly dressed gentlemen, tradesmen’s wives, peasants and artisans and beggars. All were equal in the sight of God.

There was a reading going on below, something interminable from the Prayer Book; I couldn’t distinguish the words.

‘Edward was in good spirits,’ she went on. ‘Full of himself, almost as he used to be when his father was alive. Prosperous as well, or so he would have me believe.’ There was silence, apart from sounds of the shifting crowd below and the distant gabble of the reading. Then: ‘Do you still know where to find his cousin Catherine? Just nod or shake your head.’

I nodded. The last time I had seen Edward Alderley, he had struck me as an arrogant boor, and I knew his cousin would not welcome his reappearance in her life.

‘Good. Will you take a message to her from me?’

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘He told me that he knows where she is hiding. He said it was a great secret, and I would know everything soon.’ Lady Quincy paused. ‘When he has his revenge for what she did to him. He said that he and his friends would see Catherine Lovett dead and he would dance on her grave.’

‘His friends? What friends?’

She shrugged and was silent.

I was surprised that anyone might want to make a friend of Edward Alderley. He was a bully and a braggart, with a dead traitor for a father. After his father’s disgrace last year, Lady Quincy had lost no time in reverting to the name and title she had used when married to her first husband.

In the hall below, the King was stroking the neck of the kneeling patient with his long fingers, while someone in the crowd was weeping and the clergyman was praying in an inaudible monotone. The King’s face was grave, and his heavy features gave him an air of melancholy. He was staring over the head of the kneeling woman. It seemed that he was looking up at me.

‘Do you think Alderley was telling the truth?’ I said.

Lady Quincy stirred beside me, and her arm brushed mine, just for an instant. ‘He came to …’ There was a pause, as if she needed a moment to decide what to say. ‘He came in the hope of impressing me, perhaps. Or … Or to make me afraid of him.’

‘Afraid?’ I looked towards her again, but her face was still invisible. ‘You? Why should you be afraid of him?’

‘Warn Catherine for me,’ she said, ignoring the question. ‘Promise me you will, and as soon as you can. I don’t want her death on my conscience.’

‘I promise.’

‘I believe Edward would kill her himself if he could.’ She paused, and then abruptly changed the subject. ‘I shall listen to the sermon at St Olave’s on Sunday morning. Do you know it? In Hart Street, on the corner of Seething Lane.’

I nodded. It was not far from the Tower, one of the few churches in the walled city that had survived the Great Fire.

‘Will you meet me there? Not in the church but afterwards – wait outside in a hackney. I wish to be discreet.’

‘Very well.’ I felt a stab of excitement. ‘May I ask why?’

But she had already turned away. She slipped through the crowd towards the door, followed by her small attendant, who I now saw was a lad with dark hair, presumably her footboy though he wasn’t wearing her livery. He was wrapped in a high-collared cloak that was too big for him.

Disappointment washed over me as Lady Quincy passed through the doorway to the stairs. The footboy followed his mistress. In the doorway he glanced back, and I saw that the lad was an African.

After Lady Quincy and her attendant had gone, I waited for a few minutes to avoid the risk of our meeting by accident. I left the balcony and went down to the Pebbled Court behind the Banqueting House. The sky was grey and the cobbles were slick with rain.

The public areas of the palace were packed, as they always were when the King was healing. The sufferers did not come alone: their family and friends came too, partly to support them and partly to see the miracle of the royal touch. It was unusual to have a big public healing ceremony in September, but the demand had been so great that the King had ordered it. Charles II was a shrewd man who knew the importance of reminding his subjects of the divine right of kings. What better way of demonstrating that God had anointed him to rule over them than by the miracle of the royal touch?

I crossed to the opposite corner of the court, passed through a doorway and went up to the Privy Gallery. Mr Chiffinch was waiting in the room where the Board of Red Cloth held its quarterly meetings; I was clerk to the board, and he was one of the commissioners. He was alone, because the other commissioners had already gone to dinner. He was sitting by the window with a bottle of wine at his elbow. He was a well-fleshed man whose red face gave a misleading impression of good nature.

In his quiet way, Chiffinch wielded more power than most men, for he was Keeper of the King’s Private Closet and the Page of the Backstairs, which meant that he controlled private access to the King. It was he who had told me to wait on the balcony in the Banqueting Hall until Lady Quincy approached me; he had said it was by the King’s order, and that the King relied on my discretion. He had also said that I was to do whatever her ladyship commanded.

‘Well,’ he said. ‘What did she want?’

‘I’m not permitted to say, sir.’

He shrugged, irritated but clearly unsurprised by my answer. He disliked being in a state of ignorance; the King did not tell him everything. ‘You didn’t attract attention, I hope?’

‘I believe not, sir.’

‘I’ll tell you this, Marwood: if you put a foot wrong in this business, whatever it is, we shall make sure you regret it. The King does not care for those who fail him. And he’s not in a forgiving mood at present, as my Lord Clarendon is learning to his cost.’

I bowed. A few weeks earlier, the King had removed Lord Clarendon, his oldest adviser, from the office of Lord Chancellor in one of the greatest political upheavals since the Restoration of the monarchy seven years before. But removing Clarendon from office had not made him politically insignificant. His daughter was married to Charles II’s own brother, the Duke of York. Since the King had no legitimate children, and Queen Catherine was unlikely to give him any, the Duke was his brother’s heir presumptive. Moreover, the next heirs in the line of succession were Clarendon’s grandchildren, the five-year-old Princess Mary and her infant sister, Anne. If the King were to die, then Clarendon might well become even more politically powerful than he had been before.

‘These are dangerous times,’ Chiffinch went on. ‘Great men rise and fall, and the little people are dragged up and down behind them. If my Lord Clarendon can fall, then anyone can. But of course a man can rise, as well as fall.’ He paused to refill his glass, and then went on in a softer voice: ‘The more I know, the better I can serve the King. It would be better for him, and for you, if you confided in me.’

‘Forgive me, sir. I cannot.’ I suspected that he was looking for a way to destroy the King’s trust in me.

‘It’s curious, though,’ Chiffinch went on, staring at the contents of his glass. ‘I wonder why my lady wanted to meet you in the Banqueting House of all places, at one of the healing ceremonies. She so rarely comes to Whitehall these days. Which is understandable enough. It takes more than a change of name to make people forget that she was once married to that bankrupt cheat Henry Alderley.’

I said nothing. Edward Alderley’s father had committed a far worse crime than steal other people’s money, though few people other than the King and myself were aware of that. I had done the King good service at the time of Henry Alderley’s death, which was when I had also had dealings with Lady Quincy. I kept my mouth shut afterwards, which was why he trusted me now.

Chiffinch looked up, and I saw the flash of malice in his eyes. ‘Did Lady Quincy get a good look at you, Marwood? Did she see what’s happened to you since she last saw you?’ He turned his head and spat into the empty fireplace. ‘It must have come as quite a shock. You’re not such a pretty boy now, are you?’

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_ada28456-bf00-5abd-a619-a87fd5be709d)

LATE ON FRIDAY afternoon, the rain dashed against the big windows of the Drawing Office at the sign of the Rose in Henrietta Street. It had grown steadily heavier all day, whipped up by a stiff, westerly wind. If it grew much darker they would need to light the candles.

Apart from the rain, the only sounds were the scratching of Mr Hakesby’s pen and the occasional creak of a floorboard, when Brennan, the draughtsman, shifted his weight from one foot to another. He was working on the detailed elevations for the Dragon Yard development by Cheapside, which was the main commission that Mr Hakesby had in hand at present.

Catherine Lovett was standing at a slope placed at right angles to one of the windows. Her neck and shoulders ached. She had spent the last half-hour working on another job. She was inking in the quantities and materials in a panel at one side of the plan for one of the new warehouses by the docks.

The careful, mechanical lettering was dull work, and the warehouse was a plain, uninteresting building, but Cat was thinking of something quite different – the garden pavilion project at Clarendon House, where she and Mr Hakesby had been working this morning. Mr Milcote had visited them to discuss the basement partition. Milcote was acting for his lordship in the matter, and she could not help thinking that their lives would be much more pleasant if all their clients were as agreeable and straightforward as that gentleman.

She rubbed her eyes and stretched. As she was dipping the pen in the ink, there was a tap at the door. She laid the pen aside and went to answer the knock. That was another of her more tiresome duties, along with keeping the fire going, sweeping and scrubbing the floor, filling inkwells and sharpening pens.

Cat found the porter’s boy on the landing, holding out a letter. It was addressed to Mr Hakesby in an untidy scrawl. She took it over to him. He was sitting huddled over the fire, though it was not a cold day, with a board resting over the arms of his chair so he had a surface for writing and drawing, when his hands were steady enough.

Hakesby broke the seal and unfolded the letter. It trembled in his liver-spotted hands. There was another letter inside. He frowned and gave it to her. Her name – or rather the name she used in Henrietta Street, Mistress Jane Hakesby – was written on it in the same hand as the outer enclosure.

‘What is this?’ Hakesby said, his voice petulant. ‘There’s nothing for me here. Do you know anything of this?’

Brennan looked up. He had sharp hearing and sharp wits.

‘No, sir,’ she said in a low voice.

She concealed her irritation with Hakesby, for he was increasingly peremptory with her now that he had a double reason to expect her obedience. She opened the letter and scanned its contents.

I must see you. I shall be in the New Exchange tomorrow afternoon, at about six o’clock. Look for me at Mr Kneller’s, the lace merchant in the upper gallery. Destroy this.

The note was unsigned and undated. But there was only one person who could have written it. She dropped the paper into the glowing heart of the fire.

‘Jane!’ snapped Mr Hakesby. ‘Take it out at once. Who’s it from? Let me see.’

It was too late. The flames licked the corner of the paper and then danced along one side. The letter blackened. For an instant, Cat saw one word – ‘destroy’ – but then the paper crumpled and fluttered and settled among the embers.

CHAPTER FOUR (#ulink_62aff2ce-7693-593e-b62d-03f4b4dc252e)

ON SATURDAY AFTERNOON, as chance would have it, I was kept later than I had expected at Whitehall. There was a crisis in the office. Much to Chiffinch’s irritation, I spent the majority of my time working under Mr Williamson, the Undersecretary to Lord Arlington, the Secretary of State for the South and one of the King’s most powerful ministers. Mr Williamson’s responsibilities included the publication of the London Gazette, the government’s newspaper. Under his direction, I shouldered much of the day-to-day burden of editing the material, seeing it through the press and ensuring it reached its readers.

In London, the Gazette’sdistribution relied heavily on a group of women who carried the newspapers to the taverns and coffee houses of the city, and also delivered them to the carriers who took them the length and breadth of the kingdom. Over the last few weeks there had been problems of late delivery or even no delivery at all. These were probably due to the usual causes of death, disease, drunkenness and simple unreliability. There was also the fact that we paid the women a pittance, which was often weeks in arrears. But Lord Arlington wasn’t interested in the reasons. He blamed Williamson for the failure, and Williamson blamed me.

When at last I was able to leave the office, I took a boat from the public stairs at Whitehall – fortunately the tide was on the ebb – and went by water to Charing Cross. The sun was low in the sky, slanting through a gap in the clouds.

Outside the New Exchange, the Strand was packed with waiting coaches and sedan chairs, reducing the flow of traffic in both directions to fitful trickles. Aggrieved drivers struggled towards the City or upriver to Whitehall or past the Royal Mews towards Hyde Park. Those on foot were making better speed.

The clocks were already striking six as I entered the building. Since the lamentable fire last year, which had destroyed the shops of Cheapside, the old Royal Exchange in the City and so much else, the New Exchange was busier than ever. The world came here to buy and sell. Everything the heart could desire, the proud boast went, could be found under one roof. You could purchase all the luxuries of the globe without having to get your feet muddy, your clothes wet, or your ears assaulted by the vulgar cries of the street.

I forced myself to slow down – people sauntered in the New Exchange: to hurry was to draw attention. The shops were arranged in long lines that faced each other on two floors. I made my way to the stairs. The upper galleries were even busier than those on the ground floor.

Mr Kneller’s shop was larger than most and equipped with a wide mullioned window, the better to allow customers to inspect the wares for sale. Much of his stock was imported from France and the Low Countries.

I hesitated on the threshold. The last of the sunlight slanted through the panes in broad stripes that brought to life the silks and lace in its path. The shop was thronged with people, men and women; the air was heavy with perfume, and filled with the murmur of voices and the rustle of skirts. The proprietor’s wife, a pretty woman of about thirty, was showing a delicate spray of lace to a richly dressed gentleman with a face like a horse. The gentleman was more interested in her than in her lace. For an instant her eyes flickered towards me and then returned to her customer.

‘You like the look of her, don’t you?’

My head jerked to the left. Cat was at my elbow, looking up at me. She wore a light cloak and a hat that shaded most of her face.

‘Nonsense,’ I said, instantly defensive. ‘I was looking for you.’

‘You’re a liar, sir,’ she said. ‘Like all men.’

CHAPTER FIVE (#ulink_5af887da-f19b-5dd8-b762-20c769e28b5f)

CAT ALLOWED MARWOOD to lead her to a quieter corner, partly shielded from the rest of the shop by the projecting counter on which the apprentices were laying out the larger pieces of lace. She had last seen him three or four months ago. She glanced surreptitiously at him, and found he was doing the same to her.

He looked more prosperous than before, and somehow older. He was wearing a new periwig, finer and more luxuriant than his old one. His face was plumper – the last time she had seen him, pain and laudanum had sharpened his features.

It was important to be natural: they were a man and a woman idling away an hour in the New Exchange, enjoying the pleasures of shopping. She took up a piece of lace. ‘Is this Bohemian work, I wonder?’

‘I need to talk to you,’ he muttered. ‘It’s urgent.’

‘Yes. And while you do, we need to look as if we are here to look at lace.’

She glanced up at Marwood’s face, tilting her head to have a better view of the left side of his neck. To her surprise, he gave her a sardonic but not unfriendly look.

‘Well?’ he said. ‘How do you find me?’

‘Better. As far as I can see, that is. Your wig and your collar hide the worst of it.’

He shrugged, dismissing his disfigurement, dismissing the memory of what the fire had done to him. He said softly: ‘Your aunt talked to me about you.’

Cat’s eyes widened. She raised her voice. ‘Come to the window, sir, and let me see this piece properly.’

They stood in the embrasure. The lace spilled over her arm like a frosted spider’s web. She held it to the glass and pretended to examine it.

‘Lady Quincy?’ she said. ‘What does she want, after all this time? I’m surprised she still has an interest in me. She did nothing for me when she was married to my uncle, and when we lived under the same roof, nothing when I most needed help.’

‘She wants to help you now.’

‘I’m sure she told you that, sir.’ Cat felt irritation rising like bile inside her. ‘But then you would believe anything she says. You always had a – what shall we call it? A tenderness for her.’

‘I don’t know what you’re talking about,’ he said coldly. He bent down, bringing his lips closer to her ear. ‘Your cousin Edward Alderley called on her,’ he said slowly. ‘He told her that he has discovered where you are hiding. He plans to have you brought to the gallows.’

‘Perhaps my cousin was lying,’ she said. Marwood was growing angry, she thought, which pleased her. ‘Edward never let truth get in his way.’

‘You can’t take that chance. She believed he was telling the truth. There’s still a warrant out for your arrest on a charge of treason, on the grounds that you aided and abetted your father, a Regicide. It’s never been withdrawn.’

‘But what could I do?’ she said. ‘He was my father, whatever he had done. Besides, I had as little to do with him as I could.’

‘Alderley also told Lady Quincy that he has powerful friends, and they will help him destroy you.’

‘I thought no one would give Edward the time of day after my uncle’s disgrace.’

‘It appears you were wrong,’ he said. ‘Lady Quincy believed him, and she wanted to warn you, from the goodness of her heart.’

‘Goodness? From my Aunt Quincy?’

‘You should leave Henrietta Street. At least for a time. It’s not safe.’

She flared up: ‘Why should I run away from Edward? I’ve had enough running.’

Marwood glanced at the nearest apprentice, who had heard this. He moved nearer to Cat, turning and shielding her. ‘For your safety.’

‘I’ll tell you something.’ She touched his sleeve. ‘Do you know what my cousin did to me?’

‘Yes, of course – he helped his father cheat you of your fortune, and he attacked you and—’

‘He raped me.’

‘What?’ Marwood stared aghast at her. ‘I don’t understand.’

‘What’s there to understand? In his father’s house, he came to my bedchamber by night. He took me by force. Is that plain enough for you, sir?’ She lowered her voice. ‘That’s why I took out his eye and ran away from Barnabas Place. I thought I had killed him when I stabbed him. I wish to God I had.’

The apprentice advanced and gave a little cough. ‘Sir – mistress – may I show you some more pieces? We have some particularly delicate work newly brought from Antwerp.’

‘Not now,’ Marwood said.

‘Sir, I can promise you—’

‘Leave us,’ Cat said, raising her voice. ‘Go.’

The sounds of the shop died away. Half the customers were staring openly at them. So was the shopkeeper’s pretty wife.

‘Later,’ Marwood said to the apprentice.

He took Cat’s arm and marched her out of the shop. So much for their attempts to be inconspicuous, Cat thought. She said nothing as he led her to the stairs and down to the ground floor. The movement made the curls of his periwig swing away from his face. For an instant she glimpsed what remained of his left ear.

When they reached the street, Marwood turned abruptly towards her.

‘Why didn’t you tell me what that damned knave did to you?’ he said.

‘Why should I have done? What’s it to you?’

He tightened his lips but said nothing. The last of the sun had gone. Grey clouds blanketed the city.

‘One day,’ Cat went on, in a dull voice as if mentioning a future event of no importance to her, ‘one day, I shall kill my cousin.’

‘Don’t be foolish. What would that achieve except bring you to the gallows, which is exactly what he wants?’

‘You forget yourself. You have no right to tell me what I may or may not do.’

Marwood looked away from her. ‘In any event, we must assume, for your own safety, that Alderley has found you again. That means you must leave Mr Hakesby, leave Henrietta Street. Even better, leave London for a while.’

‘I can’t.’

‘You must.’

She shook her head. ‘There’s too much work to do. Mr Hakesby depends on me. I have a meeting with one of our clients in less than an hour. I must go. Besides—’

‘If it’s a question of money, I can help. I’ve brought five pounds with me.’

That was generous, and the offer touched her.

‘You don’t understand, sir,’ she said, in a gentler voice. ‘If I need money, I shall ask Mr Hakesby. I’m betrothed to him. He will soon be my husband.’

After a good week at the Drawing Office, measured by the entries that Cat made into Mr Hakesby’s accounts, they had fallen into the habit of supping together on Saturday evening. Hakesby was careful with money but not ungenerous. There was plenty of work at present, as half of London had turned into a building site after the Fire.

Hakesby was a creature of habit, which was why he always entertained Cat and Brennan in a private room at the Lamb in Wych Street. The tavern was a shabby place, but the people of the house knew him: they valued his custom and treated his habitual ague, however bad it was, as nothing out of the way. Usually these were cheerful occasions when even Mr Hakesby allowed himself to take a glass or two of wine, though it tended to make his symptoms worse.

A few months ago, Cat would not have believed it possible that she would spend an evening in Brennan’s company. At the start of their acquaintance, she had disliked intensely both the fact that Brennan had dared to court her affections and the manner in which he had approached this impossible task. But she had dealt with that, and so had he, and she had come to respect his skill as a draughtsman, his reliability and his kindness to Mr Hakesby.

Brennan had come to Henrietta Street armed with a glowing letter of recommendation from Dr Wren, and time had justified the praise. Hakesby paid him a regular wage now, rather than using him as a piece worker. Someone, she suspected, was looking after him, perhaps the motherly young woman who worked in the pastry cook’s in Bedford Street.

On this evening, they supped later than usual, at nearer nine o’clock than eight. It was not a cold evening, but Cat was chilled to the bone. It was hard to concentrate on what the men were saying. The thought of her cousin Edward kept forcing itself into her mind. She wondered if she could ever be happy again.

At first, Hakesby and Brennan failed to notice her silence. Both of them were elated, partly from wine and partly because Hakesby had received an unexpected stage payment for the Clarendon House commission, which had allowed him to pay Brennan a bonus. Despite his political troubles, Lord Clarendon remained an influential client, the sort who led where others followed. Hakesby had been concerned about the work on the pavilion, as her ladyship, who had taken such a particular interest in it, had recently died. There was also the fact that his lordship was not only in disgrace at court but rumoured to be short of money. Nevertheless, the payment had been made. They probably had Mr Milcote to thank for that.

As the meal went on, however, Cat noticed that Hakesby was shooting worried glances at her. He was growing more and more dependent on her, she knew, and that could only increase as his ague worsened. Their marriage was fixed for the end of October; next month, they would start to call the bans. The marriage was to be a private affair in the new-built church in Covent Garden.

‘The building is a pure Inigo Jones design,’ Hakesby had said with satisfaction. ‘Not one of those crumbling medieval hotchpotches the Papists built.’

After supper, as they were going downstairs to the street, he touched Cat’s arm and said quietly, ‘Are you well? Are you sickening?’

‘No, sir. It is nothing, a woman’s matter.’

Hakesby shied away from her, turning to take Brennan’s arm. In the street, he said he would not take a chair back to his lodgings; he felt perfectly capable of walking. Brennan and Cat exchanged glances, silently accepting the necessity of accompanying him. The three of them walked slowly towards Three Cocks Yard off the Strand, where Hakesby lodged on the first floor of one of the new houses. Brennan took him into the yard and up to the house, while Cat herself lingered in the Strand.

Brennan was only gone for a moment or two. When he returned they walked back the way they had come. She would have been content to go by herself – in the past year, she had learned to cope with the streets. She always carried a knife, and was not afraid to show it. But it would make Hakesby unhappy if she walked alone after dark, so she accepted Brennan’s company. Walking back with her to Henrietta Street did not take him far out of his way.

‘What’s amiss?’ he said as they passed St Clement Danes. ‘You hardly said a word during supper.’

‘Nothing,’ she said automatically. Then she came to a sudden decision and changed her mind. ‘No. That’s not true. I – I have a difficulty. I need to go away for a while. And no one must know where I am. Even Mr Hakesby.’

‘Why?’

‘I can’t tell you.’

‘Where will you go?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘You can’t be so foolish,’ he said. ‘Is it something to do with that letter you had?’

She nodded. ‘It’s urgent. I must go, and the sooner the better.’

They walked past Somerset House. The Savoy, where Marwood lived, was not far away to the west and she pulled up her cloak to shield her face.

Brennan misinterpreted the action. ‘Do you think someone might be following you?’

‘Perhaps.’

A solitary woman always attracted attention, she thought, usually the wrong kind.

‘Would you – would you need comfort?’ Brennan said.

She stared at him, her anger flaring up. ‘What?’

‘If there were somewhere you could hide, I mean,’ he said hastily. ‘But somewhere the conditions were mean and poor, where they weren’t suitable for … you.’

‘Why?’

‘I know somewhere you could go for a week or two, longer maybe. It wouldn’t cost much.’

‘As long as I was safe, I wouldn’t need a featherbed. Or a maid to wait on me. If that’s what you mean.’

‘In that case,’ he said, ‘I have a notion that might help.’ He hesitated. ‘Though what I have in mind would hardly be fitting for one such as you. But no one would find you there. No one would even think to look there.’

‘Where is this?’

‘A few miles outside London. It’s a refugee camp, and it’s on my uncle’s land. He used to farm it, but everything’s gone to wrack and ruin since his son died.’

CHAPTER SIX (#ulink_f1fd5626-7cad-52e4-8026-584324b2f1d4)

WHEN CAT AND I had gone our separate ways, I walked down the Strand to the Savoy. My house was here, in Infirmary Close, which lay deep in the warren of crumbling buildings that made up the former palace and its immediate surroundings. The Savoy was still owned by the Crown, though its precincts were given up to a variety of purposes. I was lucky to have even a small house to myself – lodgings of any sort were in short supply, especially since the destruction of so much of London in the Great Fire. My master Mr Williamson had spoken on my behalf to the clerk who handled these royal leases.

I was not in the best of tempers. When my manservant, Sam, let me into the house and took my cloak, I swore at him for his clumsiness, though in truth he was as graceful as a man with only one whole leg can be, and more nimble than many with two of them.

Margaret, his wife, brought me my supper. She lingered by the table as I began to eat. ‘Your pardon, sir, but is it the Gazette women that’s troubling you? My friend Dorcas says they’re all at sixes and sevens and she’s worked off her feet.’

I felt ashamed of my ill humour to the servants, who were hardly in a position to answer back if they wanted to keep their places. I said, in a gentler voice than before, ‘That and other things.’

‘It’s only that perhaps I could help. If you need someone to do a few rounds for a week or so, then I will, if you permit me. Or I could share Dorcas’s load. I’ve done it before.’

It was a kind offer. Margaret had been one of the newspaper’s distributors before she came to work for me, and she was still friendly with several of the women she had worked with. She knew the routine. I also knew that she had disliked the work intensely, for the younger, more comely women often attracted unwanted attentions.

‘Thank you,’ I said. ‘But I need you here.’

I dismissed her. In a way it was useful that Margaret and Sam should think that I was out of sorts because of problems with the Gazette. Better that than the truth.

Afterwards I sat by the window, which looked out over roofs and walls. Slowly the daylight slipped away from the evening while I thought about Catherine Lovett and her ingratitude. Couldn’t the woman understand that I was trying to save her life? Why was she so headstrong? Why so foolish? Or was I the fool to put myself out on her behalf for no good reason whatsoever?

I worked myself up to a sullen rage and encouraged my sense of ill-usage to burn steadily within me. What had really upset me was the knowledge that Edward Alderley had raped Cat. And also the fact that she had betrothed herself to Simon Hakesby, a man old enough to be her father, possibly her grandfather.

I should have felt an abstract outrage that Alderley had forced himself on an unmarried cousin living under his father’s roof. As for the betrothal, I should have felt an equally abstract pleasure for Hakesby and Cat, for he would bring her security and she would bring him the vigour of a young woman.

But there was nothing abstract about my outrage. The very thought of these things made me feel inexplicably injured. So, desperate for a diversion, I fell to thinking of my Lady Quincy instead, though I found little consolation there. Tomorrow I would see her again, but I could not begin to understand why she wanted me to collect her from church in a hackney. Was it to do with her stepson, Edward Alderley, and the warning she had asked me to pass on to Cat? The possibility unsettled me. I wanted nothing further to do with Edward Alderley in this world or the next.

Something else unsettled me: the thought of seeing Lady Quincy again. Despite the difference in our stations, I had desired her once. It had been folly then, and it would be worse than folly now. Besides, as Chiffinch had reminded me, who could desire a man like me?

CHAPTER SEVEN (#ulink_bdedef5b-2c0e-591b-840c-302fca499672)

CAT MADE HER preparations. A strange calmness possessed her, a sense that her fate had already been decided and that nothing she could do would materially alter it.

In her closet she found the canvas bag she had brought with her when she came to Henrietta Street. She packed a spare shift and stockings. She would wear her old cloak. She took half a loaf that remained from breakfast. She wished she could take her Palladio, a dog-eared copy that Mr Hakesby had given her, but that was impractical: though the four books of I quattro libri dell’architettura were bound into one volume, it was a large and cumbersome folio that was hardly appropriate for a fugitive. As a consolation, she packed her notebook and a miniature travelling writing box that included a pen, ink, a ruler, a brass protractor and pencils. She had nearly thirty shillings in her purse so at least she wasn’t penniless.

Through the open window, she listened to the church clocks striking eleven. Her mouth was dry. She had spent too much of her life running away, and she did not want to do it again. She fastened the cloak over her shoulders, picked up the bag and looked around the Drawing Office. The candlelight made it insubstantial, a place of shadows and dreams. She had been happy here and she did not want to leave.

She snuffed all the candles. The only light came from the small lantern they used when they went up and down the stairs in the evening. On the landing, she locked the door behind her and slipped the key into her pocket under her skirt, where it knocked against the knife she always carried.

The light of the lantern preceded her down the stairs, swaying drunkenly from side to side. The porter had been dozing on his cot but he stirred as she reached the hallway.

‘Going out, mistress? At this hour?’

‘Didn’t I say?’ she said. ‘I’m to spend the night with an old friend. She and her father are waiting for me. Will you unbar the door?’

He shot back the bolts, one by one, and lifted up the bar. ‘It’s very late, mistress.’

‘Not really. They’ve been supping with friends and they’re waiting in Covent Garden for me.’ Cat found sixpence in her purse and gave it to him. ‘Would you do me the kindness of not mentioning to anyone that I’ve gone out? Especially Mr Hakesby. He’ll only worry, and there’s no need.’

‘Don’t you worry, mistress. Your secret’s safe with me.’ He smiled at her in a way she did not care for. ‘I’ll be silent as the grave.’

Late though it was, the arcades of Covent Garden were brightly lit and crowded with brightly dressed crowds of theatregoers, revellers and the better class of whores; among them, like lice in a head of hair, moved the thieves, the pedlars and beggars, plying their trades.

Cat had grown familiar with this world of pleasure-seekers in the last few months, and she navigated its perils with confidence. The small, forlorn figure of Brennan was waiting for her in the entrance court of the King’s Theatre in Brydges Street. He darted forward when he saw her. A link boy was beside him, the flame of his torch flaring and dancing in the breeze. By its light she saw that Brennan’s face was pale, and his sharp features were drawn with anxiety.

‘You’ve come – I wondered if you’d change your mind.’

‘Of course I’ve come,’ Cat said. ‘Were you successful?’

‘Yes. It’s all arranged. Have you got the money? If not, I can lend it—’

‘I’ve got the money.’

‘We’d better walk there.’ He hesitated. ‘Do you mind? Would you like to take my arm?’

‘Of course,’ she said. ‘Can we manage without a link boy to light us?’

He nodded. ‘I know the way well enough.’

At first they had little need of a link, for their way took them up Bow Street and into Long Acre, which were almost as busy as Covent Garden itself. Up by St Giles’s Fields, though, it was a different story, with long, unlit stretches; it was muddy underfoot and there was the constant danger of stumbling into the gutter. But Brennan was as good as his word and guided her safely, though she grew increasingly irritated by his habit of enquiring regularly how she was managing or whether he was going too fast for her.

‘I do very well, thank you,’ she snapped at last. ‘I’m not made of glass. But I’d rather save my breath for walking.’

‘Would you like me to come with you tomorrow? It’s Sunday – I’m not needed at the Drawing Office. I could walk back afterwards, when I know you’re safely there.’

‘No,’ she said. ‘It’s best I go alone. And what if Mr Hakesby finds me gone? He will send for you at once. You must be there to reassure him. Tell him you don’t know where I am but I’d said I was seeing a friend.’

The inn was a small, low building near the church of St Giles-in-the-Fields. They went through the central passageway to the yard, where there was a long range of stables.

‘Uncle Mangot doesn’t trust them,’ Brennan said in a whisper. ‘It’s not his horse, you see. It’s hired from a neighbour and he can’t afford to have it stolen. Anyway, it’s cheaper to sleep in the yard, and just as safe as inside after the gates are barred.’

They found Brennan’s uncle at the end. The horse was in its stall and the old man was in front of it, sitting in a small covered cart in the yard outside. It was difficult to see him clearly. A rushlight in an earthenware pot hung beside the cart, but his face was little more than a blur against the surrounding darkness.

Brennan hung back, touching Cat’s arm. ‘I almost forgot: if my uncle asks about me, it’s best not to mention that we’ve been working at Clarendon House.’

‘Why?’ Cat whispered.

There was a rustling of straw, and a man’s voice quavered, ‘Who’s that?’

‘Uncle Mangot,’ Brennan said. ‘It’s me. I’ve brought her.’

The man in the cart leaned towards them. ‘You’re late. Is this the girl? You’ll have to sleep here tonight, with me. We leave when it’s light.’

‘Very well,’ Cat said.

‘She’s my friend, Uncle,’ Brennan said. ‘You’ll treat her well, won’t you? You’ll let her sleep in the house? She can pay for everything.’

‘If you wish.’ The old voice sounded papery and uncertain, as if its owner rarely used it. ‘But there’s nothing to buy. She can work for her keep, eh? A long time since I had a servant.’

‘No one must know she’s with you,’ Brennan said. ‘Promise to keep her safe.’

Mangot spat over the side of the cart. ‘I won’t blab if she don’t and you don’t.’ There was a wordless sound in the darkness which might have been laughter. ‘She’ll be safe enough, Nephew. We don’t get many visitors. The refugees frighten away the ungodly.’

Cat came forward into the glow of the rushlight. ‘Five shillings,’ she said. ‘For one week. That’s what your nephew told me.’

‘And a room on her own,’ Brennan put in.

Mangot sniffed. ‘You didn’t mention that before. Seven shillings.’

Brennan tried to argue but the old man was obdurate. Cat put an end to it by taking out her purse and finding the money.

‘One more thing,’ Mangot said to her as he counted the coins in the palm of his hand. ‘You’ll have to share the cart on the way back.’

‘Who with?’ Cat said.

‘His name’s Israel Halmore. He used to be a glover. Before the Fire, he had a shop on Cheapside, and now he’s got nothing.’

Mangot’s Farm was a few miles outside London in the direction of St Albans. It was on the outskirts of a village called Woor Green.

True to his word, Mangot set out from the tavern at dawn. Cat had spent a chilly night, huddled in her cloak and half-buried beside a pile of sacks containing flour. She had shivered almost continuously, though that had not been solely because of the cold. Israel Halmore had arrived at some point in the early hours, waking her from a light sleep. He had been a long way from sober and he had fallen asleep almost at once.

As well as the flour, the cart was laden with rolls of canvas that smelled strongly of fish, and with bags of nails. Mangot was equipped with a pass signed by a magistrate, which permitted them to travel on a Sunday. The streets were quieter than usual and they made good time through the outskirts of London. Halmore woke up and insisted on their stopping so he could relieve himself against a tree. Afterwards, he sat up with Mangot and took the reins from the old man. In the daylight, he was revealed as a gaunt giant of a man, with strongly marked features and a shock of grey curls. His fingers were twisted and swollen with arthritis, which must have made it impossible for him to carry on his trade.

In the back of the cart, Cat pretended to doze while the two men talked together in low voices. Her mind was full of her own thoughts, which were bleak. Unless there were a miracle, she could not see how she could safely return to her old life in Henrietta Street. Once the hue and cry had died down, perhaps her best course would be to flee abroad, to Holland, perhaps, or even to America, where many of her father’s friends had found refuge.

She was distracted by Halmore saying, more loudly than before, ‘Well, I wasn’t going to say no, was I? Not when the Bishop was buying ale for anything on two legs.’ Mangot started to speak, but Halmore overrode him: ‘Clarendon’s a greedy rogue, master, and he’s in league with the Papists.’

‘May God damn him,’ Mangot said.

‘Aye. The Bishop’s doing God’s work in his way.’

‘But it was dangerous,’ Mangot said. ‘Notwithstanding the cause is just. You could have been arrested.’

‘No. Not me. When I was there, we were just standing outside Clarendon House and shouting and booing. I threw a few stones, but only when the light was going and no one could see who it was.’

‘Who’s this Bishop then?’ Mangot asked. ‘What’s his real name?’

‘I don’t know. But he carries a deep purse and he’s open-handed. That’s what matters.’ Halmore had a low, resonant voice that carried easily, even when he spoke quietly; a preacher’s voice. ‘We all had half a crown apiece, as well as the ale. Know what they’re saying? He’s the Duke of Buckingham’s man. That’s where the money comes from, and that’s why the Bishop said we don’t have to worry about being arrested. The Duke will see us right. He’s always been a friend of the people and a good hater of Papists. As for Clarendon, a pox on him. He deserves all we can give him. And I tell you one thing: he’s going to get a lot more before the Bishop’s done with him.’

Mangot glanced at him. ‘Meaning?’

Halmore shrugged. ‘I don’t know. Only that what they’re planning will strike him where it hurts.’

CHAPTER EIGHT (#ulink_b9741163-f67e-585e-9942-0efab00efa1b)

ST OLAVE’S WAS on the south side of Hart Street, not far from the sprawling buildings of Navy Office in Seething Lane. On Sunday morning, I waited outside the church in a hackney. It was a fine day, and I had pulled back the leather curtain so I could feel the sun on my face and watch the church door.

When the congregation emerged, I saw several men I recognized, mainly clerks from the Navy Office or the Tower. I stepped down from the coach and waited for Lady Quincy. The church was crowded, and she was one of the last to emerge from the porch. She was veiled, and flanked by her maid on one side and the footboy on the other. The maid was a prim-faced woman who avoided looking at me.

I bowed to her ladyship, and she nodded to me as she climbed into the coach and sat down, facing forwards. The boy scrambled after her, and she drew him down beside her. Despite the warmth of the day he wore the thick, high-collared cloak I had seen on Friday. I waited for the maid to follow her mistress but she walked away in the direction of Mark Lane.

‘Where to, madam?’ I asked.

‘Tell the coachman to go to Bishopsgate Street beyond the wall. I will give you further directions when we are there.’

I gave the man his instructions and joined her inside the hackney. The boy was huddled beside her. I faced them both, though I automatically turned my head a little to the right to conceal the disfigurement on the left side of my face. Lady Quincy moved aside her veil, and for the first time I saw her face clearly. I felt a pang of sadness, almost a physical pain.

Here was the reason I had put on my best suit of clothes this morning and had my periwig newly curled. Olivia, Lady Quincy, was a gentlewoman a few years older than myself; she had fine, dark eyes, a melodious voice and a full figure that her sober dress could not entirely conceal. But the living creature was not the same as the one who had played such a dramatic role in my mind for nigh on a year. She was well enough, I told myself, but one glimpsed a dozen like her every day at Whitehall, and many more beautiful.

The hackney jolted over the cobbles, and she winced. ‘Let the curtain fall,’ she commanded.

I obeyed, causing an artificial dusk to fill the interior of the coach. ‘I did what you asked me, madam. I passed on your warning to a certain young lady. But she was reluctant to flee from her cousin.’

‘She was always headstrong.’

I was tempted to tell Lady Quincy of Cat’s betrothal but I kept quiet. It was not my secret, any more than the fact that her cousin Edward had raped her.

‘Where is she? Is she somewhere safe?’

‘I don’t know,’ I said.

‘She’s a fool if she stays. Her cousin won’t leave her alone, you know. Edward nurses his hatreds as if they were his children.’

We sat in silence for a minute or two while we rattled through the noisy streets, listening to our coachman swearing at those who blocked his way.

‘Where are we going?’ I asked.

Lady Quincy looked up. ‘To see Mr Knight. He is one of the King’s Sergeant Surgeons.’

I looked sharply at her. ‘Mr John Knight? The Surgeon General himself?’

‘Do you know him?’

‘By reputation, yes.’

Knight was one of the King’s most favoured medical attendants; he had proved his loyalty during the civil war and afterwards when the court was in exile. Last year, he had corresponded frequently with Mr Williamson about the health of the Navy, which was how I had come across him. But Sunday morning was an unusual time for a consultation with a physician or surgeon, let alone one of Mr Knight’s eminence. It was yet another hint that the shadowy influence of the King was behind this.

‘Where are we meeting him?’ I asked. ‘I thought he lodged in Russell Street, not near Bishopsgate.’

‘He is visiting his wife’s cousin, and he has agreed to see us there before they dine.’

Lady Quincy took a purse from her pocket and handed it to me. ‘He will expect his fee afterwards – would you see to it for me? And the coachman will need his fare; you must ask him to wait for us while we are with Mr Knight. By the way, there’s no need to mention who I am, particularly in front of servants. You may introduce me as your cousin, Mistress Green. Our appointment is in your name, and you would oblige me if you give him the impression that Stephen is your servant.’

‘Mine?’ I stared at her. ‘Madam, it would help if I knew what we’re about.’

For a moment she said nothing. Then: ‘Pull aside the curtain.’

I did as she bid me. Light poured into the hackney.

‘Stephen? Show the gentleman what you are.’

The boy sat forward from the seat and pulled open his cloak. For the first time I saw him properly. He was richly dressed, as such African boys usually were when they served wealthy ladies; for they were kept as toys or pets as much as servants. He was handsome enough, in his way, with regular features and large eyes fringed with long lashes. But it was his neck that drew my gaze. If you kept a blackamoor as a personal attendant to serve you in public, it was fashionable to adorn the neck with a silver collar – a nod to the fact that he or she had been brought to England as a slave, and of course a sign of the owner’s wealth. This boy didn’t wear a collar, however. His neck was disfigured and bloated by swellings. He was suffering from the King’s Evil.

‘As you see, he has scrofula,’ Lady Quincy went on. ‘You must not be concerned – I believe there is no risk of infection. I took him to Whitehall to see the King touching the afflicted, to show him that there were others like himself.’ She glanced at the boy and added, ‘God has granted the King the ability to heal, as a token of his divinely ordained right to rule over us.’

‘How charitable,’ I said. I felt guilty for my earlier self-consciousness about my own blemishes, caused by a fire a few months before: if I compared them with this child’s neck, what had I to complain of?

In some small, cynical part of my mind, I thought that Stephen’s scrofula had provided perfect cover for our meeting when she had asked me to pass on the warning to Cat.

‘I wanted Stephen to see the ceremony of healing,’ she went on. ‘To reassure him. He is superstitious, you see, like all these savages, and he thought it might be a sort of witchcraft.’ She spoke as if the boy were not there.

‘And Mr Knight? Do you hope he will cure Stephen?’

Lady Quincy shook her head. ‘No – only the King can do that. But as Sergeant Surgeon he is qualified to issue certificates of scrofula, as well as the tickets for sufferers to attend the public healing ceremony. Besides, I wish to know more about the illness.’ She swallowed suddenly and her fingers made small, convulsive movements on her lap. ‘About its symptoms. And its causes.’

‘But my lady – why do you want me to escort you? Why is the appointment in my name? Why all this secrecy?’

‘Because I desire that my interest in scrofula should not be public knowledge, or not at present. That’s why I wore a veil when we met at the Banqueting House, and that’s why the appointment is in your name.’ Lady Quincy paused, and moistened her lips. ‘I have my reasons, and perhaps one day I shall confide in you. But, in the meantime, I know I may trust you to be discreet.’

The house was old and large, with many rooms and passages that seemed to have been acquired at random over the last three or four generations. It looked comfortable enough but everything was a little old-fashioned, a little shabby. There was a shop on the ground floor, though it was closed. Mr Knight’s cousin imported furs from Russia. He clearly prospered in his dealings but felt no need to advertise the fact to the world.

We were shown into a small parlour on the first floor. The servant offered us refreshments, which we declined. Mr Knight did not keep us waiting long. He brought with him a hint of wine on his breath, and the scent of cooking. The surgeon was a man who had lived much at court, and it showed in his stately manner. Though he was too polished to show impatience, I guessed that dinner was not far away and he did not want to prolong this interview any longer than he needed.

After we had introduced ourselves, I told Stephen to come forward and expose his neck.

‘So this is the boy,’ Mr Knight said. ‘How interesting. I believe I have never seen a blackamoor afflicted with the disease. I must make a note of it.’

He beckoned Stephen closer and examined him. His long, deft fingers were surprisingly gentle. Lady Quincy, her face veiled, leaned forward in her chair to watch.

‘Is it the King’s Evil?’ she asked.

‘Oh yes, mistress. There’s no doubt about that. And in an advanced state. The inflation is at present mainly in the neck, with the characteristic rosy colour. Tilt your head back, boy. Yes, I thought so. The hard tumours are propagating vigorously under the jaw and about the fauces …’

Knight straightened and turned towards us. ‘There will be no difficulty about providing you with a certificate stating that he has scrofula. And, in the circumstances’ – he gave a little bow, perhaps in respect of the King’s possible interest in the matter – ‘I will also write you a special ticket of admission for the next public healing ceremony. Otherwise the boy would have to present himself with his certificate at my house in Russell Street before the ticket can be issued. That can sometimes take months, because there is always such a crowd of sufferers.’

‘Thank you, sir,’ I said.

‘Tell me,’ Lady Quincy said. ‘How is the disease caused? What is its nature?’

He took a chair and leaned back, steepling his fingers. ‘These are most interesting questions. As Hippocrates observes, he who knows the nature of the disease can be at no great loss for the properest method of cure. But I regret to say we don’t fully understand scrofula, not completely. Generally it is characterized by an indolent tumour or – as in this case – several tumours.’ He prodded Stephen’s neck, and the boy recoiled. ‘Yes, the struma yields. This one – the one on the left here, under the jawbone – will probably degenerate into a stubborn ulcer within the month.’

‘And the causes, sir?’ she prompted, and again I saw the curious flutter of her fingers on her lap. I wondered at her agitation.

‘Well – let me enumerate some of them, or rather the conditions that may lead to the disease. We find it particularly in children descended from parents who also are disfigured by it. (What a pity we usually cannot examine them.) Or in those suckled by nurses who were themselves diseased. Or who have lived much in humid air.’ He poked Stephen again. ‘Africa is humid, is it not?’

The boy stared blankly at him, his eyes wide and fearful.

I guessed he didn’t understand the word. I said, ‘The gentleman means damp, Stephen. Was it damp where you lived before you were brought to England?’

He twitched his head like a nervous horse confronted by something he does not understand. Mr Knight took this as assent.

‘There you are,’ he said. ‘I’m not surprised. Another cause is undoubtedly diet – viscous, crude, farinaceous aliments, in particular, or unripe fruit. Or lack of healthful exercise. Or the possession of a frigid or phlegmatic temperament.’ He frowned. ‘The boy certainly looks phlegmatic. Is his bile inert, by the way?’

I’ve shrugged. ‘I’ve no idea.’

Knight hurried on, anxious to smooth over an awkwardness. ‘External injuries – luxations, for example, or strains – or even catarrhs and fevers may lead towards scrofula. Or drinking stagnant water. There are some physicians who hold that a mother who has looked much upon a scrofulous person may, as it were, imprint the disease on her own child.’

Lady Quincy made no comment. I said, ‘These are underlying causes, if I understand you correctly, sir. Are there factors that incite an outbreak of the disease in a person already predisposed towards it?’

‘Well, sir – here there is some debate in the profession. Most of us, I think, would agree that the proximate cause is probably the obstruction of the small vessels by a viscid, inert humour. There are some, however, who attribute it rather to a particular acidity of the blood, which causes it to coagulate and then harden.’

‘What is the best method of treatment, sir?’ Lady Quincy asked.

Mr Knight smiled condescendingly. ‘There is none of proven efficacy apart from His Majesty’s touch. By God’s mercy he has cured thousands of sufferers. Why, by my calculations, he must have stroked some thirty thousand of his subjects. No wonder the people love their King and venerate God. We are blessed indeed.’

‘Indeed,’ said Lady Quincy drily. ‘Thank you for your advice. I believe you and Mr Marwood have a little business to transact. I shall wait here while you do it.’

Mr Knight and I left her alone with Stephen. At my request, he ordered a servant to bring our hackney to the street door. He took me into a small room overlooking the street. It was furnished plainly as a counting house. There was a terrestrial globe in the corner. A map of Muscovy had been unrolled on the table, its corners held down with pebbles.

While the surgeon was writing Stephen’s certificate of scrofula and his ticket of admission for the next public ceremony, I stood at the window and stared idly down at the street. A tall and very thin man in a long brown coat was standing on the far side of the road. He was plainly dressed – he might have been a merchant in a small way. But what caught my attention was the fact that he wore a sword, as if he were a gentleman or a bully from the stews of Alsatia: yet he looked neither a rogue nor a man of birth.

He glanced up at the windows of the house. Perhaps he saw me, though he could not have made out more than a shadow on the other side of the lozenges of distorted glass. He strolled away. I forgot him for the moment as soon as Mr Knight spoke to me.

‘There, sir. The next ceremony will probably be at the Banqueting House, unless the King goes down to Windsor. If there is any difficulty, give my name to the Yeoman on duty at the door.’

I thanked him, and paid his fee. With great ceremony, he escorted us downstairs and handed Lady Quincy into the hackney, where the maid was already waiting. Stephen and I followed her.

Sitting in near darkness, with the leather curtain drawn across, we rattled down the street towards Bishopsgate. Lady Quincy’s perfume filled the confined space.

‘Thank you for your help, sir,’ she said. ‘You will not speak of this to anyone, I’m sure.’

‘You have my word, madam.’ I wondered whether she would ask me to accompany her to her house in Cradle Alley, and perhaps offer me some refreshment.

‘And I will not trespass further on your time. I shall put you down by the Wall.’

‘Of course,’ I said, telling myself firmly that the less I saw of her the better. ‘That would be most convenient.’

CHAPTER NINE (#ulink_2b0b37ea-59d4-5df2-ad7b-7ba8669c7023)

IT WAS RAINING again on Monday morning, and harder than before. I stood by a window in the Matted Gallery and looked down on the Privy Garden. The hedges and statues had a bedraggled air, and large puddles had formed on the gravel paths. Only two or three people were in sight, and they were in a hurry, using the garden as a shortcut.

The gallery ran on the first floor between the garden and the river. When I had first come to Whitehall, I had despaired of ever finding my way around such an ill-arranged and confused cluster of buildings. Gradually, though, I had realized that there was a certain logic to the place. At its core were the Royal Apartments, the King’s and Queen’s, both public and private. From these, two long ranges extended at right angles to each other, enclosing two sides of the Privy Garden. The old Privy Gallery ran westwards to the Banqueting Hall and the Holbein Gate. Here were many of the offices and chambers of government, such as the Council Chamber and Lord Arlington’s offices. The Stone Gallery, with the Matted Gallery above, ran south towards Westminster. The apartments of many favoured courtiers clustered about it. Those of the Duke of York were at the far end.

On this wet morning, the gallery was crowded with courtiers, officials and visitors. Gentlemen strolled up and down, and the air was full of whispered conversations and smothered laughter. It was a popular place of resort, a place to see and be seen, especially when the weather was bad. It had the added convenience of giving access to so many private apartments.

Today there was an air of suppressed excitement. The story was circulating that the Duke of Buckingham, one of Lord Clarendon’s greatest enemies, had been restored to his many offices yesterday and was once again riding high in the King’s favour. Buckingham was a hero to the common people and had wide support in Parliament. He had been the King’s intimate friend since childhood, having been brought up with the royal family, and he was extraordinarily rich. Nevertheless, until recently he had been held in the Tower: it had been alleged by his enemies that he had commissioned an astrologer to cast the King’s horoscope, which was a form of treason since predicting the King’s future inevitably imagined the possibility of his death.

I was waiting for Mr Chiffinch again. He had sent a note to the office this morning, summoning me to attend him here on the King’s business. Mr Williamson had let me go with reluctance, muttering that the Gazette would not publish itself. While I waited, I could not help thinking of Cat Lovett and Lady Quincy. They were not happy thoughts. They matched the weather.

There was a sudden stir by the entrance to the King’s private apartments. The doors were flung open. The guards straightened themselves, and the crowd fell silent. The Duke of York, the King’s brother, strode into the gallery, flanked by two of his advisers.

Ignoring the bows of courtiers, who bent towards him like corn in the wind, he marched towards his own apartments. The Duke was a fine-looking man, but today his face was red and his features were twisted with rage. When he left the gallery, the whispers began again, with an edge of excitement that they had previously lacked.

I moved from the window and instead examined a painting of a lady that hung nearby. She wore a richly embroidered silk black gown with ballooning sleeves and a gold chain around her neck. She stared past me, over my right shoulder, at something only she could see. The embroidery of the gown looked like writhing snakes. Behind her, a group of women were entering her suite of rooms through a distant doorway.

Ten or fifteen minutes slipped past before the King’s doors opened again. This time it was Chiffinch who emerged, pink-faced like a well-fed baby, nodding and smiling to those nearby whom he considered worth cultivating. He didn’t linger, however. He came over to me.

‘How interesting to find you here,’ he said, his eyes sliding past me to the painting.

‘I don’t understand, sir.’

‘That lady you were looking at. The widow in her black gown. She has a look of Lady Quincy, don’t you think?’

I shrugged. ‘Perhaps a little, sir. But her ladyship is not so sallow, I think.’

It disturbed me that Chiffinch had mentioned her. He had a genius for finding a man’s weak spots. I wondered if he had sensed my interest in Lady Quincy.

‘Her ladyship’s lips are fuller,’ Chiffinch said, pursing his own.

‘Who is it?’

‘I’ve no idea. Some long-dead Italian princess, probably. The Dutch gave it to the King at the Restoration.’ He turned away from the painting. ‘Come with me.’ He led me into the Privy Gallery and took me into a closet by the King’s laboratory, which overlooked the garden.

‘Close the door,’ he ordered. ‘Sit.’

He pointed at a chair by a small table underneath the window. He sat opposite me and leaned over the table, bringing our heads close together.

‘I’ve a commission for you, Marwood. Do you remember Edward Alderley?’

I was so surprised I couldn’t speak.

‘Alderley,’ Chiffinch said irritably. ‘For God’s sake, man, you can’t have forgotten. That affair you were mixed up in after the Fire with my Lady Quincy’s second husband. Edward Alderley was the son by his first wife. He used to be at court a great deal.’

‘Yes, sir. Of course I remember him.’

‘He’s dead.’ He paused, fiddling with the wart on his chin. ‘I daresay no one will shed many tears.’

I felt shock, swiftly followed by relief. What a stroke of luck for Cat. ‘How did he die?’

‘Drowned. But it’s not that he is dead that matters. It’s where his body was found.’ Chiffinch’s forefinger abandoned the wart and tapped the table between us. ‘In Lord Clarendon’s well.’

I began to understand why the Duke of York had been in such a rage. Lord Clarendon was the Duke’s father-in-law. ‘In my lord’s house?’

‘In his garden. Which comes to the same thing. But mark: this is a confidential matter. Breathe a word of it to anyone, and you will regret it. Do you understand?’

‘Yes, sir. But are you sure that I am the man best suited to a matter of such delicacy?’

‘You wouldn’t be my choice for the job, I can tell you that. It’s by the King’s command. I suppose he chose you because you know a little of the man and his family.’

Then there was no hope for me. ‘What do you want me to do?’ I asked.

‘Go to Clarendon House and look into the circumstances of Alderley’s death. The body is under lock and key. Lord Clarendon knows, of course, and so does one of his gentlemen, Mr Milcote. Alderley was discovered this morning by a servant, who has been sworn to secrecy. We don’t want the news made public yet. Not until we know more. That is essential.’

‘Was the death accidental, sir?’

Chiffinch flung up his arms. ‘How in God’s name would I know? That’s for you to find out. Report back to me as soon as you can.’

‘Mr Williamson—’

‘May go to the devil for all I care. But I shall see he’s informed that the King has given you a commission. He can hardly object.’ Chiffinch glanced piously in the direction of heaven. ‘After God, our duty is to serve the King. We would all agree on that, I hope.’

I nodded automatically. The more I thought about this, the less I liked it. I had been long enough at Whitehall to know that when the great ones of our world squabbled among themselves, it was the little ones who tended to be hurt.

Chiffinch drew a paper from his pocket. ‘Here’s your authority, with the King’s signature.’ He held the paper in his hand, but did not give it to me. ‘Remember. My Lord Clarendon is no longer Lord Chancellor, but he still has many friends who would like to see him restored to the King’s favour. And one of them is the Duke.’ He paused, which gave me time to reflect on the fact that the Duke of York was the King’s heir presumptive, and that the Duke’s daughters – Clarendon’s grandchildren – were next in line to the throne. ‘So for God’s sake, Marwood, go carefully. And if you see my lord himself, try not to anger him. He has had much to cope with lately. Bear in mind that his wife has hardly been a month in her grave.’

He sent me away. With my mind heavy with foreboding, I walked slowly through the public apartments, through the Guard Chamber and down into the Pebble Court. It was still raining, even more heavily than before.

I was to go immediately to Clarendon House, but on my way I had to call at the Gazette office in Scotland Yard to collect my cloak and my writing materials. I was tempted to scribble a note to Cat, care of Mr Hakesby, while I was there, to give her private warning of her cousin’s death. But I dared not ignore Mr Chiffinch’s prohibition until I knew more of the matter.

Besides—

A thought struck me like a blow in the middle of the court. I stopped abruptly. Rain dripped from the brim of my hat.

How could I have been so foolish? Not two days earlier, I had told Catherine Lovett that her cousin had found her out. And she had told me that he had raped her when she lived under her father’s roof, and that she meant to kill him for it.

From any other person, that might have been merely an extravagant way of speaking, a way of expressing hatred. But not from Cat. She was a literal-minded creature in many ways, and a woman of great spirit. I had seen what she was capable of. And now Edward Alderley was dead.

I faced the dreadful possibility that Cat had somehow contrived to kill her cousin. Worse still, that I had played a part in causing the murder, by warning her that her cousin had found her.

CHAPTER TEN (#ulink_ea33133e-692a-5b17-abbd-8001002c902f)