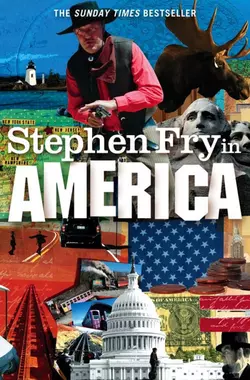

Stephen Fry in America

Stephen Fry

Britain's best-loved comic genius Stephen Fry turns his celebrated wit and insight to unearthing the real America as he travels across the continent in his black taxicab. Stephen's account of his adventures is filled with his unique humour, insight and warmth in the fascinating book that orginally accompanied his journey for the BBC1 series.'Stephen Fry is a treasure of the British Empire.' - The GuardianStephen Fry has always loved America, in fact he came very close to being born there. Here, his fascination for the country and its people sees him embarking on an epic journey across America, visiting each of its 50 states to discover how such a huge diversity of people, cultures, languages, beliefs and landscapes combine to create such a remarkable nation.Starting on the eastern seaboard, Stephen zig-zags across the country in his London taxicab, talking to its hospitable citizens, listening to its music, visiting its landmarks, viewing small-town life and America's breath-taking landscapes - following wherever his curiosity leads him.Stephen meets a collection of remarkable individuals - American icons and unsung local heroes alike. Stephen starts his epic journey on the east coast and zig-zags across America, stopping in every state from Maine to Hawaii. En route he discovers the South Side of Chicago with blues legend Buddy Guy, catches up with Morgan Freeman in Mississippi, strides around with Ted Turner on his Montana ranch, marches with Zulus in New Orleans' Mardi Gras, and drums with the Sioux Nation in South Dakota; joins a Georgia family for thanksgiving, 'picks' with Bluegrass hillbillies, and finds himself in a Tennessee garden full of dead bodies.Whether in a club for failed gangsters (yes, those are real bullet holes) or celebrating Halloween in Salem (is there anywhere better?), Stephen is welcomed by the people of America - mayors, sheriffs, newspaper editors, park rangers, teachers and hobos, bringing to life the oddities and splendours of each locale.A celebration of the magnificent and the eccentric, the beautiful and the strange, Stephen Fry in America is our author's homage to this extraordinary country.

Stephen Fry inAMERICA

Stephen Fry

DEDICATION (#ulink_1b053c43-a691-5b0e-bd7e-7f856a27b232)

For Steve.Who so nearly existed…

CONTENTS

Cover (#u4fc3d639-eaff-5dac-8f51-149a4da172b2)

Title Page (#u7b16f732-1cdb-5445-b3a5-d9c99f8fde75)

Dedication (#ua9625575-ee13-56ee-b8fd-6e550f60c3e3)

Introduction (#uc7c5f448-4920-509a-9a52-666a99388895)

New England and the East Coast (#u26126f92-d232-55ec-8149-88e5b605b77a)

Maine (#ue319ee2e-fc5f-54bf-ad2f-aa006fe0e5d9)

New Hampshire (#u6f9cfeb7-f4a9-5257-b190-eb96bdea2878)

Massachusetts (#u1b1ec846-0e5c-5127-967f-760ed47d2c73)

Rhode Island (#u365cf7be-15bd-5388-bbbe-c8a0755491a9)

Connecticut (#u59a58244-bb6a-5fde-8751-f782178dd16a)

Vermont (#u81da7a4b-fbcd-5ae4-ae61-d467e1ea90bd)

New York State (#u2b68dbee-d99b-5644-980b-d03c72967702)

New Jersey (#u80e1e632-a44f-5f26-b763-066f447d6a48)

Delaware (#ufc82a2fe-9e60-5aea-9c31-fbac71b2ebdc)

Pennsylvania (#u881cb9a5-50f9-5765-82ce-a48ea65e50f7)

Maryland & Washington D.C. (#litres_trial_promo)

South East and Florida (#litres_trial_promo)

Virginia (#litres_trial_promo)

West Virginia (#litres_trial_promo)

Kentucky (#litres_trial_promo)

Tennessee (#litres_trial_promo)

North Carolina (#litres_trial_promo)

South Carolina (#litres_trial_promo)

Georgia (#litres_trial_promo)

Alabama (#litres_trial_promo)

Florida (#litres_trial_promo)

The Deep South and the Great Lakes (#litres_trial_promo)

Louisiana (#litres_trial_promo)

Mississippi (#litres_trial_promo)

Arkansas (#litres_trial_promo)

Missouri (#litres_trial_promo)

Iowa (#litres_trial_promo)

Ohio (#litres_trial_promo)

Michigan (#litres_trial_promo)

Indiana (#litres_trial_promo)

Illinois (#litres_trial_promo)

Wisconsin (#litres_trial_promo)

Minnesota (#litres_trial_promo)

The Rockies, the Great Plains and Texas (#litres_trial_promo)

Montana (#litres_trial_promo)

Idaho (#litres_trial_promo)

Wyoming (#litres_trial_promo)

North Dakota (#litres_trial_promo)

South Dakota (#litres_trial_promo)

Nebraska (#litres_trial_promo)

Kansas (#litres_trial_promo)

Oklahoma (#litres_trial_promo)

Colorado (#litres_trial_promo)

Texas (#litres_trial_promo)

The Southwest, Pacific Northwest, California, Alaska and Hawaii (#litres_trial_promo)

New Mexico (#litres_trial_promo)

Utah (#litres_trial_promo)

Arizona (#litres_trial_promo)

Nevada (#litres_trial_promo)

California (#litres_trial_promo)

Oregon (#litres_trial_promo)

Washington (#litres_trial_promo)

Alaska (#litres_trial_promo)

Hawaii (#litres_trial_promo)

American English (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#ulink_ca912d87-fe06-56a6-b0c9-41c0b6d5783f)

I was so nearly an American. It was that close. In the mid-1950s my father was offered a job at Princeton University – something to do with the emerging science of semiconductors. One of the reasons he turned it down was that he didn’t think he liked the idea of his children growing up as Americans. I was born, therefore, not in NJ but in NW3.

I was ten when my mother made me a present of this momentous information. The very second she did so, Steve was born.

Steve looked exactly like me, same height, weight and hair colour. In fact, until we opened our mouths, it was almost impossible to distinguish one from the other. Steve’s voice had the clear, penetrating, high-up-in-the-head twang of American. He called Mummy ‘Mom’, he used words like ‘swell’, ‘cute’ and ‘darn’. There were detectable differences in behaviour too. He spread jam (which he called jelly) on his (smooth, not crunchy) peanut butter sandwiches, he wore jeans, t-shirts and basketball sneakers rather than grey shorts, Airtex shirts and black plimsolls. He had far more money for sweets, which he called candy, than Stephen ever did. Steve was confident almost to the point of rudeness, unlike Stephen who veered unconvincingly between shyness and showing off. If I am honest, I have to confess that Stephen was slightly afraid of Steve.

As they grew up, the pair continued to live their separate, unconnected lives. Stephen developed a mania for listening to records of old music hall and radio comedy stars, watching cricket, reading poetry and novels, becoming hooked on Keats and Dickens, Sherlock Holmes and P.G. Wodehouse and riding around the countryside on a moped. Steve listened to blues and rock and roll, had all of Bob Dylan’s albums, collected baseball cards, went to movie theatres three times a week and drove his own car.

Stephen still thinks about Steve and wonders how he is getting along these days. After all, the two of them are genetically identical. It is only natural to speculate on the fate of a long-lost identical twin. Has he grown even plumper than Stephen or does he work out in the gym? Is he in the TV and movie business too? Does he write? Is he ‘quintessentially American’ in the way Stephen is often charged with being ‘quintessentially English’?

All these questions are intriguing but impossible to settle. If you are British, dear reader, then I dare say you too might have been born American had your ancestral circumstances veered a little in their course. What is your long-lost non-existent identical twin up to?

Most people who are obsessed by America are fascinated by the physical – the cars, the music, the movies, the clothes, the gadgets, the sport, the cities, the landscape and the landmarks. I am interested in all of those, of course I am, but I (perhaps because of my father’s decision) am interested in something more. I have always wanted to get right under the skin of American life. To know what it really is to be American, to have grown up and been schooled as an American; to work and play as an American; to romance, labour, succeed, fail, feud, fight, vote, shop, drift, dream and drop out as an American; to grow ill and grow old as an American.

For years then, I have harboured deep within me the desire to make a series of documentary films about ‘the real’ America. Not the usual road movies in a Mustang and certainly not the kind of films where minority maniacs are trapped into making exhibitions of themselves. It is easy enough to find Americans to sneer at if you look hard enough, just as it is easy to find ludicrous and lunatic Britons to sneer at. Without the intention of fawning and flattering then, I did want to make an honest film about America, an unashamed love letter to its physical beauty and a film that allowed Americans to reveal themselves in all their variety.

Anti-Americanism is said to be on the rise around the world. Obviously this has more to do with American foreign policy than Americans as people. In a democracy, however, you can’t quite divorce populace from policy. Like any kind of racism there are the full-frontal and the casual kinds.

I have often felt a hot flare of shame inside me when I listen to my fellow Britons casually jeering at the perceived depth of American ignorance, American crassness, American isolationism, American materialism, American lack of irony and American vulgarity. Aside from the sheer rudeness of such open and unapologetic mockery, it seems to me to reveal very little about America and a great deal about the rather feeble need of some Britons to feel superior. All right, they seem to be saying, we no longer have an Empire, power, prestige or respect in the world, but we do have ‘taste’ and ‘subtlety’ and ‘broad general knowledge’, unlike those poor Yanks. What silly, self-deluding rubbish! What small-minded stupidity! Such Britons hug themselves with the thought that they are more cosmopolitan and sophisticated than Americans because they think they know more about geography and world culture, as if firstly being cosmopolitan and sophisticated can be scored in a quiz and as if secondly (and much more importantly) being cosmopolitan and sophisticated is in any way desirable or admirable to begin with. Sophistication is not a moral quality, nor is it (unless one is mad) a criterion by which one would choose one’s friends. Why do we like people? Because they are knowledgeable, cosmopolitan and sophisticated? No, because they are charming, kind, considerate, exciting to be with, amusing … there is a long list, but knowing what the capital of Kazakhstan is will not be on it. Unless, as I repeat, you are mad.

The truth is, we are offended by the clear fact that so many Americans know and care so very little about us. How dare they not know who our Prime Minister is, or be so indifferent as to believe that Wales is an island off the coast of Scotland? We are quite literally not on the map as far as they are concerned and that hurts. They can get along without us, it seems, a lot better than we can get along without them and how can that not be galling to our pride? Thus we (or some of us) react with the superiority and conceit characteristic of people who have been made to feel deeply inferior.

I do not believe, incidentally, that most Britons are anti-American, far from it. Many are as fascinated in a positive way by the United States as I am, and if their pride needs to be salvaged by a little affectionate banter then I suppose it does little harm.

So I wanted to make an American series which was not about how amusingly unironic and ignorant Americans are, nor about religious nuts and gun-toting militiamen, but one which tried to penetrate everyday American life at many levels and across the whole United States. What sort of a design should such a series have? What sort of a structure and itinerary? It is a big country, the United States, and surely …

The United States! America’s full name held the clue all along, for America, it has often been said, is not one country, but fifty. If I wanted to avoid all the clichés, all the cheap shots and stereotypes and really see what America was, then why not make a series about those fifty countries, the actual states themselves? It is all very well to talk about living and dying, hoping and dreaming, loving and loathing ‘as an American’, but what does that mean when America is divided into such distinct and diverse parcels? To live and die as a Floridian is surely very different from living and dying as a Minnesotan? The experience of hoping and dreaming as an Arizonan cannot have much in common with that of hoping and dreaming as a Rhode Islander, can it?

So, to film in every state. I had a structure and a purpose. It suddenly seemed so obvious and so natural that I was amazed no British television company had ever done it before. But how would I get about? I often drive around in a London taxi. The traditional black cab is good and roomy for filming in and perhaps the sight of one braving the canyons, deserts and interstate highways of America could become a happy signature image for the whole journey. A black cab it would be.

There is no right tempo for a project like this. The whole thing could be achieved in two weeks by someone who just wanted to tick off the states like a train-spotter, or it could be done over the course of years, with great time and attention given to the almost infinite social, political, cultural and physical nuances of each state. The pace at which my taxi and I zipped along provided me not with definitive portraits but with multiple snapshots of experience, which I hope when taken together will cause a bigger picture of the country and its fifty constituent parts to emerge.

Between these pages I have been more anxious to convey the experience than to interpret it – in other words, while this is a book about a journey, it does not presume to draw conclusions. I would not dare to suggest that my trip, though as exhausting and exhaustive as we could make it, has granted me a definitive insight into so complex and gigantic a nation as America, nor even a definitive insight into each state. I do hope however, that it will communicate the scale of the nation, the diversity, depth of identity and wealth of pride that prevails in every one of its fifty distinct states. I hope too that it will fill in some gaps for those of you, who – like me – might have been rather unsure where Wisconsin, say, or Nebraska exactly fitted on the map, who wanted to know a little more about the Deep South, the Heartland, New England, the Pacific Northwest, the Delta and the Great Lakes, the Rocky and the Smoky Mountains, the wide Mississippi and High Plains and the people who live out their lives in these remarkable places. You can, of course, use this book as a quick reference when you need to remind yourself where Vermont is, or what the state capital of Kansas might be and you can try your hand at the little quizz I have included at the end of the book. If you use a gentle pencil to fill in your answers, then others can have a go too …

Having said that this book presumes to draw no conclusions, I will offer this: the overwhelming majority of Americans I met on my journey were kind, courteous, honourable and hospitable beyond expectation. Such striking levels of warmth, politeness and consideration were encountered not just in those I was meeting for on-camera interview, they were to be found in the ordinary Americans I met in the filling-stations, restaurants, hotels and shops too.

If I were to run out of petrol in the middle of the night I would feel more confident about knocking on the door of an American home than one in any other country I know – including my own. The friendly welcome, the generosity, the helpfulness of Americans – especially, I ought to say, in the South and Midwest – is as good a reason to visit as the scenery. Yes, Americans are terrible drivers (endlessly weaving between lanes while on the phone, bullying their way through if they drive a big vehicle, no waves of thanks or acknowledgement, no letting other cars into traffic), yes, they have no idea what cheese or bread can be and yes, strip malls, TV commercials and talk radio are gratingly dreadful. But weighing the good, the kind, the original, the enchanting, the breathtaking, the hilarious and the lovable against the bad, the cruel, the banal, the ugly, the crass, the silly and the monstrous, I see the scales coming down towards the good every time.

If you are an American you will, I hope, accept my apologies for such statements of the obvious, such errors of fact and judgement, such generalisations and misapprehensions as will be painfully evident to you, privileged as you are with that almost unconscious knowledge and instinctive understanding of your native state and nation that comes with citizenship. Human nature, after all, dictates that you turn straight to the entry in this book that covers your own state, and you will doubtless find that your home town has been ignored and that I have passed over all the ingredients you regard as essential in the make-up, character and identity of your state, and this might poison your mind against my judgement. My eyes, those of an outsider looking in, are bound to miss and to misinterpret. As it happens, I enjoy reading impressions of Britain written by visitors to our shores; the mistakes and misreadings only add to the pleasure and often make me think about my country in new ways, so perhaps my sweeping inaccuracies and dumb failures to grasp the essentials can be taken in that light, as revealing rather than obscuring. Sometimes the spectator sees more of the game. In any event, few if any Americans I met in my travels had ever visited all fifty states, or anything close to that number, so perhaps even you will find something new here.

There is one phrase I probably heard more than any other on my travels: ‘Only in America!’

If you were to hear a Briton say ‘Tch! Only in Britain, eh?’ it would probably refer to something that was either predictable, miserable, oppressive, dull, bureaucratic, queuey, damp, spoilsporty or incompetent – or a mixture of all of those. ‘Only in America!’ on the other hand, always refers to something shocking, amazing, eccentric, wild, weird or unpredictable. Americans are constantly being surprised by their own country. Britons are constantly having their worst fears confirmed about theirs. This seems to be one of the major differences between us.

We began filming the series in Maine in late September 2007 and finished in Hawaii in the first week of May, 2008.

At 6.45 a.m. on my very first morning I was sitting in the WaCo Diner, which styles itself ‘America’s eastmost dining-room’. Marvelle prepared a Seafood Scramble for me while her colleague Darna replenished my coffee cup for the third time. Endless free refilling or ‘bottomless coffee’ as they call it is the norm in diners all across the United States. How outraged Americans are when they come to Europe and find themselves charged for each cup. Anyway, the television at the end of the counter was running a commercial for a local telecoms company. And that is where I heard a refrain that, mutatis mutandis, followed me over the next eight months as I travelled from sea to shining sea: ‘In Maine we don’t always follow the rules. We sometimes make our own. In Maine we think different.’

Those words, surely somewhat overblown in the context of a television advertisement for a local phone network, confirmed my suspicions about American statal pride. ‘We think different in Tennessee’, ‘South Dakotans march to a different drum’, ‘We don’t follow the pack in New Mexico’, ‘I guess you can call us Missourians mavericks’… and so on.

We all like to think ourselves different, ‘I’m unconventional like everybody else,’ as Wilde once almost said, but it seems particularly important to Americans to remind themselves of their separateness, their uniqueness, their rebel spirit and they do it, not so much as a nation, but state by state.

And which of the states is my personal favourite? I have been asked that a great deal and I have yet to come up with a smart, snappy answer. A combination of Montana, northern California, Arizona, Maine and Alaska would be pretty impressive. But I have left out Utah, Wyoming and Massachusetts and where are Vermont and Kentucky? Am I saying I didn’t like Pennsylvania and South Carolina? Oh dear. Without the loyalty that comes from being actually born in one of the states it seems impossible to choose between them. I could live in most of them perfectly happily. Living the life I do, I would have to make my choice according to conveniences like proximity to a major American city. Thus to have Chicago, Boston, New Orleans, San Francisco or New York within reach would tilt the balance away from Montana, Arizona and Maine, for example. Yet I could live happily in any of those three if I were to retire from the kind of work that makes access to a large urban centre necessary.

As the taxi and I travelled around America I pictured myself in an adobe on the edges of the Saguaro Park outside Tucson, Arizona, in an artfully luxurious beachfront shack on the New England coast, in a Colorado condo in the shadow of the Rockies, in an Italianate villa in the Napa Valley, in a gracious antebellum residence in the lowlands of South Carolina, in a modern glass-fronted creation built into the hillside overlooking Puget Sound in Seattle, Washington, in a Ted Turner-style ranch house in Montana, in an elegant townhouse in a historic square in Savannah, Georgia or in a traditional clapboard, clinker-built home with a view over Chesapeake Bay, Maryland. Any one of those would suit me fine.

Damn, I was lucky to be able to do what I did. I hope you find in the pages to come information and experience which will encourage you to think again about America. Maybe you will even consider following in my tyre-treads on your own trip of a lifetime.

Take your own cheese.

SF – June 2008

NEW ENGLAND AND THE EAST COAST (#ulink_369dc6fe-6b05-5541-9304-369b6a776ce5)

MAINE (#ulink_bf962ac0-9584-5732-b2de-7eff2e3d9bf3)

KEY FACTS

Abbreviation:

ME

Nickname:

The Pine Tree State

Capital:

Augusta

Flower:

White pinecone

Tree:

Eastern white pine

Bird:

Black-capped chickadee

Motto:

Dirigo (‘I lead’)

Well-known residents and natives:

Edward Muskie, Dorothea Dix, Winslow Homer, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Edna St Vincent Millay, Artemis Ward, E.B. White, Stephen King, John Ford, Patrick Dempsey, Jonathan Frakes, Liv Tyler, Judd Nelson.

MAINE

‘I can assure you of this. If I find a friendlier, more welcoming and kinder set of people in all America than Mainers I will send you film of me eating my hat.’

Squeezed by Canada on two sides and connected to the rest of America by a straight-line border with New Hampshire, Maine is home to a million and a quarter citizens who roam roomily around a land larger than all of Scotland.

The southeast half of the state is where the urban action is. Portland and Bangor are the big towns; the former is the birthplace and home town of Stephen King, the novel laureate of Maine, whose prolific output has stayed loyal to the state for over thirty years. But I’m heading north, passing through Portland, Augusta and Bangor, getting used to how much of a head-turner my little London taxi will be. Augusta, with one of the lowest populations of any of the fifty state capitals, seems small, depressed and depressing. I hurry through on my way Down East. ‘Down’, in Maine-speak, means ‘Up’.

With the exception of Louisiana and Alaska whose administrative districts are called parishes and boroughs respectively, all the American states are divided into counties. These are much like their British counterparts, but with sheriffs who are real live law-enforcement officers rather than our ceremonial figureheads in silly costumes. Every US county has its chief town and administrative headquarters, known as the County Seat. The number of counties in each state will vary. Florida, for example, has 67, Nebraska 93 and Texas 254. Maine has just 16 and at the top right of this topmost, rightmost state you will find Washington County, the easternmost county in all America. My destination is Eastport, the easternmost town in that easternmost county.

Down East

The most obvious physical features of the Down East scenery are forest and ocean. But then this is true of the whole state. Mainers will tell you that if you were to straighten every wrinkle and crinkle of their coastline it would stretch out wider than the whole breadth of the United States – into three and half thousand miles of inlets, creeks, coves, bays, promontories, spits, sounds and headlands. As for the land – well, there is only ten per cent of Maine that is not forest and much of that is lake and river. Water and wood, then – water and wood everywhere.

They will also tell you that Eastport was once famed for its sardine-packing industry. ‘Fame’ is an odd thing in America. There cannot be many towns with a population of more than ten thousand that do not make some claim to it. It usually comes in the form of a burger: ‘Snucksville, NC – home of the world famous Snuckyburger’, a dish that will never have been heard of more than five miles from its originating diner. But ‘back in the day’ Eastport genuinely was famous for sardines. An industry, that, if the Eastporters are to be believed, was effectively wrecked by The Most Trusted Man In America.

The doyen of news anchors, Walter ‘and that’s the way it is’ Cronkite liked apparently to sail in the waters around Eastport and was disturbed one day to see a film of oil all over the water, staining the trim paintwork of his yacht. He made complaints. A government agency looked at the fish oil coming from the cannery and imposed regulations so strict that the economic viability of the business was compromised and the industry left Eastport for good. That at least is the story I was told as gospel by many Eastporters. Certainly the deserted shells of the old canneries still brood over the harbour awaiting their full regeneration. The body of water that dominates the harbour is Passamaquoddy Bay and the land on the other side is, confusingly, Canada. A line straight down the middle of the bay forms the border between the two countries.

Before the British, before the French, before any Europeans came to Maine there were the tribesmen, the ‘First Nations’ or Native Americans, as I expected I should have to be very careful to call them. Actually the word ‘Indian’ seems inoffensive to the tribespeople I speak to around town. The federal agency is still called The Bureau of Indian Affairs and there are Indian Creeks and Indian Roads and Indian Rivers everywhere. It is true that the word was wrongly applied to the native tribes by Columbus and his settlers who thought they had landed in India. But the word stuck, misnomer or not. Sometimes political correctness exists more in the furious minds of its enemies than in reality, which gets on with compromise and common sense without too much hysteria.

Anyway, the indigenous peoples of the Maine/New Brunswick area are the Passamaquoddy, a European mangling of their original name which meant something like ‘the people who live quite close to pollock and spear them a lot from small boats’, which may not be a snappy title for a tribe but can hardly be faulted as a piece of self-description.

My first full day in Eastport will see me on Passamaquoddy Bay, not spearing pollock, but hunting a local delicacy prized around the world.

Lobstering

The word Maine goes before the word lobster much as Florida goes before orange juice, Idaho before potato and Tennessee before Williams. Three out of four lobsters eaten in America, so I am told, are caught in Maine waters. There are crab, and scallop and innumerable other molluscs and crustaceans making a living in the cold Atlantic waters, but the real prize has always been lobster.

Angus McPhail has been lobstering all his life. He and his sons Charlie and Jesse agree to take me on board for a morning. ‘So long as I do my share of work.’ Hum. Work, eh? I’m in television …

‘You come aboard, you work. You can help empty and bait the pots.’

The pots are actually traps: crates filled with a tempting bag of stinky bait (for lobsters are aggressive predators of the deep and will not be lured by bright colours or attractively arranged slices of tropical fruit) that have a cunning arrangement of interior hinged doors designed to imprison any lobster that strays in. These cages are laid down in long connected lines on the American side of the border. Angus, skippering the boat, has all the latest sat nav technology to allow him to mark with an X on his screen exactly where the lures have been set. To help the boys on the deck, a buoy marked with the name of the vessel floats on the surface above each pot. Americans, as you may know, pronounce ‘buoy’ to rhyme not with ‘joy’ but with ‘hooey’.

How is it that work clothes know when they are being worn by an amateur, a dilettante, an interloper? I wear exactly the same aprons and boots and gloves as Charlie and Jesse. They look like fishermen, I look like ten types of gormless arse. Heigh ho. I had better get used to this ineluctable fact, for it will chase me across America.

It is extraordinarily hard work. The moment we reach a trap, the boys are hooking the line and hauling in the pot. In the meantime I have been stuffing the bait nets with hideously rotted fish which I am told are in fact sardines. The pot arrives on deck and instantly I must pull the lobsters from each trap and drop them on the great sorting table that forms much of the forward part of the deck. If there are good-looking crabs in the traps they can join the party too, less appetising specimens and species are thrown back into the ocean.

Lobsters of course, are mean, aggressive animals. But who can blame them for wanting a piece of my hand? They are fighting for their lives. Equipped with homegrown cutlery expressly designed to snip off bits of enemy, they don’t take my handling without a fight.

As soon as the trap has been emptied I’m at the table, sorting. This sorting is important. Livelihoods are at stake. The Maine lobstermen and marine authorities are determined not to allow over-fishing to deplete their waters and there is fierce legislation in place to protect the stocks. Jesse explains.

‘If it’s too small, it goes back in. Use this to measure.’

He hands me a complicated doodad that is something between a calibrated nutcracker and an adjustable spanner.

‘Any undersized lobsters they gotta go back in the water, okay?’

‘Don’t they taste as good?’

A look somewhere between pity and contempt meets this idiotic remark. ‘They won’t be full-grown, see? Gotta let them breed first. Keep the stocks up.’

‘Oh, yes. Of course. Duh! Sorreee!’ I always feel a fool when in the company of people who work for a living. It brings out my startling lack of common sense.

‘If you find a female in egg, notch her tail with these pliers and throw her back in too.’

‘In egg? How do I …?’

‘You’ll know.’

How right he was. A pregnant lobster is impossible to miss: hundreds and hundreds of thousands of glistening black beads stuck all round her body like an over-fertile bramble hedge thick with blackberries.

‘Notch her tail’ is one of the things that takes a second to say and three and a half minutes of thrashing, wrestling and swearing to accomplish. The blend of curiosity, amusement and disbelief with which I am watched by Jesse and Charlie only makes me feel hotter and clumsier.

‘Is this strictly necessary?’

‘The inspectors find any illegal lobsters in our catch they’ll fine us more’n we can afford. They’ll even take the boat.’

‘How cruel!’

‘Just doing their job. I went to school with most of them. Go out hunting in the woods with them weekends. That wouldn’t stop them closing us down if they had to.’

‘Done it!’ I hold up one properly notched pregnant female. Jesse takes a look and nods, and I throw her back into the ocean.

‘Good. Now you gotta band the keepers.’

‘I’ve got to what the which?’

The mature, full-sized, non-pregnant lobsters the crew don’t have to throw back are called ‘keepers’ and it seems that a rubber band must be pulled over their claws and that I am the man to do it.

Charlie hands me the device with which one is supposed to pick up a band, stretch it and get it round the lobster’s formidably thick weaponry in one swift movement. Charlie demonstrates beautifully: this implement however marks me down as an amateur as soon as I attempt to pick it up and in a short while I am sending elastic bands flying around the deck like a schoolboy at the back of the bus.

‘Otherwise they’ll injure each other,’ explains Charlie.

‘Yes, fine. Of course. Whereas this way they only injure me. I see the justice in that.’ I try again. ‘Ouch. I mean, quite seriously, ouch!’

It transpires that lobsters, if they had their way, would prefer not to have elastic bands limiting their pincers’ reach, range and movement and they are quite prepared to make a fuss about it. The whole operation of sorting and banding is harder than trying to shove a pound of melted butter into a wildcat’s left ear with a red-hot needle in a darkened room, as someone once said about something. And what really gets me is that just as I finish sorting and am ready to turn my mind to a nice cup of tea and a reminisce about our famous victory over the lobsters, Charlie and Jesse send down a fresh pot, Angus moves the boat on and another trap is being pulled aboard.

‘You mean one has to do more than one of these?’ I gasp.

‘We make about thirty drafts a day.’

A draft being the pulling-up, emptying and re-baiting of a trap.

Oh my. This is hard work. Gruellingly hard work. The morning we make our run is a fine sparkling one with only the mildest of swells. The McPhails go out in all weathers and almost all seas.

You have probably seen TV chefs like Rick Stein spend the day with fishermen and pay testament to their bravery and fortitude. We can all admire the bold hunters of the deep, especially these artisanal rather than industrial fishers like the McPhails, crewing their small craft and husbanding the stocks with respect, skill and sensitivity. But until you have joined them, even for one morning, it is hard truly to appreciate the toil, skill, hardiness and uncomplaining courage of these men, and yes it is exclusively men who go out to sea in fishing boats.

They do it for one reason and one reason only. Their families. They have wives and children and they need to support them. There are not many jobs going in Down East Maine, not much in the way of industry, no sign of Starbucks, malls and service-sector employment. This is work on the nineteenth-century model. This is labour.

Given how hard their days are you might think they end each night in bars drinking themselves silly. Actually they need to be home in time for a bath and bed, for the next morning they will be up again at four. It is perhaps unsurprising to hear Jesse tell me that he wants his own sons to do any work other than this. Maybe we should prepare for the price of lobster to go up in our restaurants and fishmongers. Whatever these men make, it surely isn’t enough.

From the Sea to the Table

Lobsters, it seems to me, are simply giant marine insects. Huge bugs in creepy armour. Look at a woodlouse and then a lobster. Cousins, surely? And look at the flesh of a lobster and then at a maggot. Exactly. Cover them in mayonnaise and Frenchify them all you will, lobsters are insects: scary scuttling insects.

None of which stops them from tasting de-mothering-licious of course. And it is with lip-smacking anticipation that I jump off Angus’s lobsterman and prepare to feast on our catch at Bob del Papa’s Chowder House right on the quayside. Bob del Papa is … well, he is as his name leads you to hope he might be, big, amiable, powerful-looking and hospitable. He came up from Rhode Island many years ago having served his country and learned his seamanship with the United States Coastguard. There doesn’t seem to be much in Eastport that Bob doesn’t own, including the lobsters themselves. He buys them from the fishermen and sells them on to whoever then gets them finally to the restaurant kitchens of America. Bob is far from your typical desk and chair entrepreneur however – he drives the forklift, hauls the crates, cooks the food and sweeps the yard. He is very determined that I should enjoy a Maine lobster properly served with all the correct accoutrements and habiliments traditionally associated with a Maine lobster dinner and takes great pleasure in preparing a grand feast.

We eat right out on the dockside. A big pot is hauled onto a gas ring and a long trestle table laid against the wall and under a canopy to protect it from the rain that is beginning to fall. Bad weather instantly sends the British inside, but in Maine they seem to be made of hardier stuff. An al fresco banquet was prepared and an al fresco banquet we shall all have. One by one Bob’s friends and neighbours start to arrive; everyone is grinning and rubbing their hands with pleasurable anticipation.

Before tossing each lobster to its boiling fate it is possible to hypnotise them, or at least send them into a strange cataleptic trance. Bob teaches me how to place one upright on a table and firmly stroke the back of its neck: after a surprisingly short while it freezes and stays there immobile. It is to be hoped that this state will deprive it of even a millisecond of scalding agony when finally into the pot it falls. While dozens of them boil away in the cauldron for nine or ten minutes, turning from browny-bluey-coral to bright cardinal red, I sit myself down and allow Bob’s staff of smiling waitresses to serve the first course.

We start with cups of Clam Chowder, the celebrated New England soup of cream, potatoes, onions, bacon, fish stock and quahogs. These last, now made immortal in the name of the home town in Family Guy, are Atlantic hard-shelled clams, a little larger than the cherrystone or little-neck clams which also abound in these fruitful waters. From Maine to Massachusetts a cup of chowder is traditionally served with ‘oyster’ crackers, small saltine-style biscuits crumbled into the soup to thicken it further. A little white pepper makes the whole experience even more toothsome, but don’t even think of adding tomato. This is actually illegal in Maine, thanks to a piece of 1939 legislation specifically outlawing the practice. It may be good enough for ‘Manhattan Chowder’, which I am told is no more than Italian clam soup rebranded, but the real New England deal must be creamy white and tomato free. Like so many enduring local dishes, chowder has an especial greatness when consumed in its land of origin. We all know how delicious retsina is sipped on a Greek island and yet how duff it tastes back home. Well, I don’t think Clam Chowder is ever duff, but eaten on a quayside in Down East Maine, even in the driving rain, it is to my mind and stomach as close to perfect as any dish can be. Until the lobster arrives, that is.

Each of us is given a pair of crackers, a pot of coleslaw, a bib, a tub of melted and clarified butter and a great red lobster. I recognise mine as one who gave me an especially painful nip earlier in the day so it is with regrettable but understandable savagery that I tear him to pieces, dipping his maggot-flesh with frenzied delight into the ghee and fully justifying the bib, which – I notice – I am the only one wearing.

Bob del Papa claps me on the shoulder. ‘Dunt get much bedder ’n this, does it?’

I take another sip of the supernacular wine and swallow another piece of the sensational blueberry pie that Bob himself baked. The late afternoon sun pushes through the clouds on its way down west where all the rest of America lies.

‘No, Bob, it doesn’t. It truly does not.’

But I was wrong.

Left Right Center

That night Bob takes me to the Happy Crab, a magnificent eatery run by two expat Britons from Leicester, where he initiates me into Left Right Center (the American spelling of centre is, one feels, obligatory), a dice game of startling simplicity and fun. He even gives me a set of dice. I plan to make it the latest gaming sensation in London.

It was inexpressibly touching to discover how much the Mainers want me to love their state. An easy wish to grant. At one point Bob even speculates on which states I might prefer, as if this grand tour was a competition. ‘I’m worried about Montana. Ve-e-ery beautiful. Nice people. Hell, if it had a coastline I might even live there myself. Yep, I’m worried you might like Montana more than Maine. But you think we’ll be in the top ten?’

I do not laugh, for I see how seriously the issue concerns him.

‘There are no top tens,’ I say, ‘but I can assure you of this. If I find a friendlier, more welcoming and kinder set of people in all America than the Down East Mainers I will send you film of me eating my hat.’

NEW HAMPSHIRE (#ulink_77b7b899-ca0c-5ca0-b47b-7122114180a6)

KEY FACTS

Abbreviation:

NH

Nickname:

The Granite State

Capital:

Concord

Flower:

Purple lilac

Tree:

White birch

Bird:

Purple finch

Motto:

Live Free or Die

Well-known residents and natives:

Josiah Bartlett, Daniel Webster, Horace ‘Go West, Young Man’ Greeley, Mary Baker Eddy, Brooke Astor, Robert Frost, Grace Metalious, J.D. Salinger, John Irving, P.J. O’Rourke, Ken Burns, Adam Sandler.

NEW HAMPSHIRE

‘What is it with Americans and cinnamon?’

If the word lobster is forever yoked to Maine then who can separate from New Hampshire the word ‘primary’? But what the heck is a primary, let alone a New Hampshire one? Something to do with politics one is almost certain but what, precisely?

Primaries in the USA are election races for the presidential nomination. There are, as I expect you know, two parties in American politics: the Democrats (symbol, a donkey or jackass) and the Republicans (the Grand Old Party, symbol an elephant). When the time for presidential elections comes, each party must field a candidate: and who that candidate might be is decided by the outcome of primaries (and caucuses and conventions, but we’ll leave them for the time being). Only registered members of the Republican Party can vote for Republican candidates and only registered Democrats for theirs. Like many American institutions it makes sense, is very democratic, transparent and open but comes down, fundamentally, to race, religion, media and – most of all – money.

And why is the New Hampshire primary so important? Because it is traditionally the first of the cycle to be held. The primacy of the New Hampshire primary derives primarily from its prime position as the primary primary. To lose badly here can dish a candidate’s chances from the get-go, as they like to say, while to win first out of the traps can impart valuable momentum. Huge amounts of money and effort are expended by all the runners and riders here.

The people of New Hampshire, one of the smallest states in physical size and population, although also one of the most prosperous, are treated every four years to more political speeches, sincere promises, sunny compliments and rosy blandishments than any other citizens in America … in the world possibly.

The presidential election takes place every four years, 2004, 2008, 2012 and so on. The primaries begin in the preceding years, 2003, 2007, 2011. I arrive in Manchester, New Hampshire in October, 2007 – just as the primary season for the 2008 elections is hotting up. We now all know who won, of course, but as I knock on the door of a certain campaign office, I am certain of nothing other than that it appears to be a close race for both parties. The Democrats are going to have to choose between Hillary Clinton, Chris Dodd, John Edwards, Barack Obama and Bill Richardson. The Republicans have Rudy Giuliani, Mike Huckabee, John McCain, Mitt Romney and Fred Thompson. So the next US President could be a woman, a Mormon, a Latino, an African-American, a Baptist minister or a television actor … there are certainly plenty of firsts on offer.

On the Road with Mitt

I am welcomed to the office by a very pretty young girl called Deirdra, the name and the red hair offering picture-book testament to her Irish ancestry. She is one of the many hundreds, indeed thousands, of students and young people who dedicate their time at this season to helping their chosen candidate. Her guy, and for this day my guy too, is Republican Mitt Romney.

‘I just love him. He’s awesome.’

‘What’s different about him?’ I wonder.

‘I saw him last year, just about like before he announced? Just listening to him speak, his charisma and such is mindboggling.’

Whatever my own political views, and they happen not to coincide strikingly with those of Governor Romney, I am touched to be trusted so much by the campaign team, who leave me free to follow Deirdra around, handing out fliers, badges (Americans call them buttons) and posters and attending to the low-level but necessary grunt work that devolves to a young campaign keenie.

As a matter of fact, my production team and I had also approached Clinton’s and Obama’s people on the Democratic side who, true to their donkey nature, were obstinate and would not budge: no behind the scenes filming. Both Giuliani’s and Romney’s teams were only too happy to help us out, no strings attached. I was simultaneously impressed and disappointed by the laid-back, friendly and calm atmosphere of the campaign office. I had expected and rather looked forward to the frenzy, paranoia and brilliant, fast-talking, wise-cracking repartee of the TV series West Wing.

Deirdra and I watched Mitt make a speech at a hospital and then at a family home. These ‘house parties’ are ‘Meet Mitt’ events where local people turn up and are encouraged to ‘just go ahead and ask Mitt anything’. A tidy lower-middle-class home in Hooksett, NH, has been chosen complete with standard Halloween garden decorations and an aroma of cinnamon. What is it with Americans and cinnamon? The smell is everywhere; they flavour chewing gum with it, they ruin wine and coffee with it, they slather it over chicken and fish … it is all most peculiar.

Deirdra and I turn up armed with pamphlets only minutes before the Governor himself arrives. The excitement is palpable: the householders, Rod and Patricia, are so proud and pleased they look as if they might burst; all their friends and neighbours have gathered, video news crews are lined up pointing at the fireplace whose mantelpiece is replete with miniature pumpkins, artfully stuffed scarecrows and dark-red candles scented with, of course, cinnamon.

With a great flurry of handshakes and smiles Mitt is suddenly in the house, marching straight to the space in front of the fireplace where a mike on a stand awaits him, as for a stand-up comedian. He is wearing a smart suit, the purpose of which, it seems, is to allow him to whip off the jacket in a moment of wild unscripted anarchy, so as to demonstrate his informality and desire to get right down to business and to hell with the outrage and horror this will cause in his minders. British MPs and candidates of all stripes now do the same thing. The world over, male politicians have trousers that wear out three times more quickly than their coats. And who would vote for a man who kept his jacket on? Why, it is tantamount to broadcasting your contempt for the masses. Politicians who wear jackets might as well eat the common people’s children and have done with it.

Romney is impressive in a rather ghastly kind of way, which is not really his fault. He has already gone over so many of his arguments and rehearsed so many of his cunningly wrought lines that, try as he might, the techniques he employs to inject a little life and freshness into them are identical to those used by game-show hosts, the class of person Governor Romney most resembles: lots of little chuckled-in phrases, like ‘am I right?’ and ‘gosh, I don’t know but it seems to me that’, ‘heck, maybe it’s time’ and so on. In fact he is so like an American version of Bob Monkhouse in his verbal and physical mannerisms that I become quite distracted. Rod and Patricia beam so hard and so shiningly they begin to look like the swollen pumpkins that surround them.

‘Hey, you know, I don’t live and die just for Republicans or just for whacking down Democrats, I wanna get America right,’ says Mitt when invited to blame the opposition.

A minder makes an almost indiscernible gesture from the back, which Mitt picks up on right away. Time to leave.

‘Holy cow, I have just loved talking to you folks,’ he says, pausing on the way out to be photographed. ‘This is what democracy means.’

‘I told you he was awesome,’ says Deirdra.

In the afternoon we move on to Phillips Exeter Academy, one of the most famous, exclusive and prestigious private schools in the land, the ‘Eton of America’ that educated Daniel Webster, Gore Vidal, John Irving, and numerous other illustrious Americans all the way up to Mark Zuckerberg, the creator of Facebook as well as half the line-up of indie rockers Arcade Fire. The school has an endowment of one billion dollars.

In this heady atmosphere of privilege, wealth, tradition and youthful glamour Mitt is given a harder time. The students question the honesty of his newly acquired anti-gay, anti-abortion ‘values’. It seems he was a liberal as Governor of Massachusetts and has now had to add a little red meat and iron to his policies in order to placate the more right-wing members of his party. The girls and boys of the school (whose Democratic Club is more than twice the size of its Republican, I am told) are unconvinced by the Governor’s wriggling and squirming on this issue and he only just manages, in the opinion of this observer at least, to get away with not being jeered. I could quite understand his shouting out, ‘What the hell you rich kids think you know about families beats the crap out of me’, but he did not, which is good for his campaign but a pity for those of us who like a little theatre in our politics.

By the time he appeared on the steps outside the school hall to answer some press questions I was tired, even if he was not. The scene could not have been more delightful, a late-afternoon sun setting the bright autumnal leaves on fire; smooth, noble and well-maintained collegiate architecture and lawns and American politics alive and in fine health. I came away admiring Governor Romney’s stamina, calm and good humour. If every candidate has to go through such slog and grind day after day after day, merely to win the right finally to move forward and really campaign, then one can at least guarantee that the Leader of the Free World, whoever he or she may be, has energy, an even temper and great stores of endurance. I noticed that the Governor’s jacket had somehow magically been placed in the back of his SUV. Ready to be put on in order to be taken off again next time.

Bretton Woods

New Hampshire is more than just a political Petri dish, however; it is also home to some of the most beautiful scenery in America. The White Mountains are a craggy range that form part of the great Appalachian chain that sweeps down from Canada to Alabama, reaching their peak at Mount Washington, the highest point in America east of the Mississippi, at whose foothills sprawls the enormous Mount Washington Hotel at Bretton Woods. Damn – politics again.

I never studied economics at school and for some reason I had always thought that the ‘Bretton Woods Agreement’ was, like the Hoare – Laval pact, the product of two people, one called Bretton and one called Woods. No, the system that gave the world the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and stable exchange rates based on a decided value for gold was the result of a conference in 1944 here in Bretton Woods, attended by all the allied and non-aligned nations who knew that the post-war world would have to be reconstructed and developed within permanent and powerful institutions. The economic structure of the world since, for good and ill, has largely flowed from that momentous meeting – if structures can be said to flow.

The hotel is certainly big enough to house such a giant convention. It is hard not to think of Jack Nicholson and The Shining as I get repeatedly lost in its vast corridors and verandas. I sip tea and watch the huge vista of a misty, drizzly afternoon on the mountains recede into a dull evening. If fate is kind to me, the next day will dawn bright and sunny. Perfect for an expedition to the summit. Unlikely, for Mount Washington sees the least sunshine and the worst weather of anywhere in America. That is an official fact.

Fate is immensely kind, however. Not only does she send a day as sparklingly clear as any I have seen, but she also makes sure that the train and cog line are in prime working order so I can make my way up the 6,000 feet in comfort and without the expenditure of a single calorie, all of which – thanks to my American diet – have far too much to do swelling my tummy to be bothered with exercise. A steam locomotive – nuzzle pointing cutely down ready to push us all up the hill – puffs gently at the foothills. This rack and pinion line has been taking tourists and skiers to the top of Mount Washington for over a hundred and forty years. I join a happy crowd of people on board. The ‘engineer’ (which is American for engine driver) does something clever with levers at the back of the train and after enough clanking and grinding we are off. Up front, the grimy-faced brakeman tells me a little about the locomotive.

‘This was the first,’ he says proudly.

‘What the first in the world?’

‘Yep.’

It wasn’t actually, but I haven’t the heart to tell him. The world’s first cog railway was in Leeds, England, but the Mount Washington line was the first ever to go up a mountain, and that’s what counts.

Up we go, pushed by the engine at no more than a fast walking pace. You can almost hear the locomotive wheeze ‘gonnamakeit, gonnamakeit, gonnamakeit!’ And make it we do.

New Hampshire? The highest point in Old Hampshire that I have ever visited is Watership Down, a round green hillock famous for its bunny rabbits. The great granite crags of the White Mountains are a world away from the soft chalk downs of the mother country. The sheer scale is dizzying. I feel as if I have visited two huge countries already and all I have done is take a look round a couple of America’s smaller states.

The Appalachians and I have a long way still to go before we reach the south. I gaze down as they march off out of view. What a monumentally, outrageously, heart-stoppingly beautiful country this is. And how frighteningly big.

MASSACHUSETTS (#ulink_7acae3ec-338d-519f-82f7-ebd9f5e3572e)

KEY FACTS

Abbreviation:

MA

Nickname:

The Bay State

Capital:

Boston

Flower:

Mayflower

Tree:

American elm

Bird:

Chickadee

Motto:

Ense petit placidam sub libertate quietem (‘By the sword she seeks peace under liberty’)

Well-known residents and natives:

Paul Revere, John Adams (2nd President), John Quincy Adams (6th), Calvin Coolidge (30th), John F. Kennedy (35th), George H.W. Bush (41st), John Hancock, Benjamin Franklin, Susan B. Anthony, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Robert Kennedy, Edward Kennedy, Michael Dukakis, John Kerry, Mitt Romney, John Harvard, Eli Whitney, Elias Howe, Samuel Morse, Alexander Graham Bell, James McNeill Whistler.

MASSACHUSETTS

‘By twelve o’clock it’s all over and everyone is in bed. There’s more true Gothic horror in a digestive biscuit, but never mind.’

Massachusetts prides herself on being a commonwealth rather than a state. It is a meaningless distinction constitutionally but says something about the history and special grandeur of this, the most populous of the New England states. Cape Cod, Martha’s Vineyard, the Kennedys, Harvard University, Boston … there is a sophisticated patina, a ritzy finish to the place. It has its blue-collar Irish, its rural poor but the image is still that of patrician wealth and founding history. And a quick glance up at the list of notable natives shows that American literature in the first two hundred years of the nation would not have amounted to much without Massachusetts. Maybe having to learn how to spell the name of the state inculcated a literary precision early on …

Whaling

Much of the prosperity of nineteenth-century Massachusetts derived from the now disgraced industry of whaling. The centre of this grisly trade was the island town of Nantucket, now a neat and pretty, if somewhat sterile, heritage and holiday resort. It is a pompous and priggish error to judge our ancestors according to our own particular and temporary moral codes, but nonetheless it is hard to understand how once we slaughtered so many whales with so little compunction.

I am shown round the whaling museum by Nathaniel Philbrick, the leading historian of the area, a man boundlessly enthusiastic about all things Nantuckian.

‘The whaling companies were the BPs and Mobils of their day,’ he says as we pass an enormous whale skeleton. ‘The oil from sperm whales lit the lamps of the western world and lubricated the moving parts of industry.’

‘But it was such a slaughter …’

Nathaniel hears this every day. ‘Can’t deny it. But look what we’re doing now in order to get today’s equivalent. Petroleum.’

‘Yes, but …’

‘The Nantucket whalers depredated one species for its oil, which I don’t defend, but we tear the whole earth to pieces, endangering hundreds of thousands of species. We fill the air with a climate-changing pollution that threatens all life, including all whales.’

The awful devastation to the whale on the one hand and the unquestionable courage, endurance and skill displayed by the whalers on the other has been Nathaniel’s theme as a writer for many years now.

‘How will our descendants look at us?’ he wonders, as we look down on Nantucket from the roof of the museum. ‘Only a sanctimonious fool could deny the valour and hardiness of the New England whalers. But will our great-grandchildren say the same about the oil explorers and oil-tanker crews?’

A petroleum-burning ferry takes us away from Nantucket, past Hyannisport, the home to this day of the Kennedy compound: ‘Yeah, saw old Ted sailing just yesterday afternoon,’ the ferry captain tells me. ‘Gave me a wave, he did.’

The Pilgrims

I drive along the coast to Plymouth, Massachusetts where they keep a replica of the Mayflower, the ship that carried a boatload of Puritans from Plymouth, Devon to the coast of America in 1620–21. These Pilgrim Fathers have been given, almost arbitrarily one might think, the iconic status of nation-builders; it is almost as if Plymouth Rock is the very rock on which America itself was built. The turkeys those pilgrims killed for food and the sour cranberries they ate with them in their first hard winter are annually memorialised on the third Thursday of every November in the great American feasting ritual known as Thanksgiving. Those who can trace their ancestry back to the pilgrims count themselves almost a kind of aristocracy.

I enjoy a morning clambering about the boat listening to the heritage talk and watching parties of American schoolchildren having the legend of the Pilgrim Fathers reinforced in their young minds.

‘I be John Harcourt, out of Plymouth, Hampshire,’ declaims a bearded man in a leather jerkin.

‘No you baint,’ I tell him firmly. ‘You be an actor, out of New York City.’

Only I say no such thing because I am too polite. The ship is crewed by Equity members in smocks and leather caps whose idea of an English accent is to say ‘thee’, ‘thou’ and ‘my lady’ and trust to luck.

‘Do thee hail from the Old Country?’ I am asked.

‘No, no, no!’ I am once more too polite to say. ‘You mean “Dost thou” – “Do thee” makes no sense.’

The idea that the Puritans came to New England to avoid persecution is lodged firmly in the American psyche. Gore Vidal’s view that they came, ‘not to be free from persecution, but on the contrary, to be free to persecute’ while heretical to America’s vision of itself is to some extent born out in the literature of Hawthorne and the decidedly murky regimes of tyranny, bigotry and intolerance under which the citizens of the New World were forced to live in the early days. Quakers, for example, were persecuted, suppressed, tortured and discriminated against in much of New England throughout the early years of the colonies. But I suppose the tortuous alteration of real history and the elevation of the Pilgrim Fathers to heroic status was important for America, which needed to create a vision of itself consonant with its lofty aims. I dare say Robin Hood was a greedy cut-throat and Boadicea a cruel tyrant – all nations twist history and cleanse their heroes in order to express an ideal to live up to.

Nowhere in America is the religious intolerance and fanaticism of the early colonies more apparent, or more weirdly celebrated, than in the small town of Salem, MA.

The Witches

Halloween is the first of America’s great winter festivals of celebration and commerce, followed by Thanksgiving and completed by Christmas (or the Holidays, as they are usually called, in deference to non-Christians) and New Year. Children across America go trick-or-treating dressed up as ghosts, monsters, gore-spattered zombies or, somewhat inexplicably, superheroes. For weeks before the actual day houses and gardens (‘yards’) are decorated with scarecrows, gravestones, pumpkins and autumn fruits creating a weirdly pagan mélange of Wicker Man Celtic, Transylvanian Gothic and Parish Harvest Festival.

In the late seventeenth century an attack of mass hysteria in Salem, Massachusetts resulted in a series of witch trials, judicial torture and hangings. Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible famously used the episode as a metaphor for the Communist ‘witch-hunts’ of his own time. The shameful, primitive and disgusting events of the 1690s have receded into jokey folk lore and Salem now embraces its position as the Halloween and Olde Puritan capital of America, abounding with Publick Houses and Crafte Shoppes. Indeed there are now real witches in Salem, witches who are Out and Proud.

‘Can you feel the positive energy here?’

‘Er, well, since you mention it, not really …’

I meet High Priestess Laurie Cabot in her occult shop ‘The Cat, The Crow and The Crown’, the first of its kind, she claims, anywhere in the world. She and her co-religionists have fought long and hard for ‘the Craft’ to be treated as any other faith under the constitution. Laurie is the ‘Official Witch of Massachusetts’, a title granted by Governor Dukakis in the seventies. She is not to know that I am entirely allergic to anyone using the word ‘energy’ in a nonsensical, New Age way. A hundred years ago it would have been ‘vibrations’. I am determined not to be surly and unhelpful, however, so I plough on.

‘Big day for you, today, Laurie. Halloween.’

‘Today is not Halloween,’ she says, putting me right, ‘it is the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain. The Christians took it over, along with so much else.’ There is no black cat perched on her shoulder, but there might as well be. ‘The Christians went from persecuting us to scorning us for what they call superstition.’

I murmur sympathy, which is genuine. To me, all religions are equally nonsensical and the idea that Christians, with their particular invisible friends, virgin births, immaculate conceptions and bread turning into flesh, could have the cheek to mock people like Laurie for being ‘superstitious’ is appalling humbug.

Laurie invites me to a great Samhain meeting (I forbear from using the word ‘coven’ for I have an inkling it might offend); it is to be held not naked and out of doors, leaping through flames and around pentacles, but in the ballroom of The Hawthorne Hotel. No black candles, no reciting of the Lord’s Prayer backwards. This is not Hammer House of Horror but a kind of syncretic New Age mixture of Druidism, Celtic folklore and much vague talk about ‘energies’.

The meeting itself is a very charming party in which the Cabot-style witches who have come from all over the world to be here dress up, dance (to seventies and eighties pop mostly) and then come forward for a ‘circle’ in which a sword is waved, incantations are made and ‘energies’ invoked. It is all over very quickly and then Laurie and I get on with the business of judging the best costume of the evening.

Meanwhile outside, the entire town of Salem has turned into a huge horror and gore theme park. The smell of donuts and burgers, the sound of rock music, the sight of murder, mayhem and death. By twelve o’clock it’s all over and everyone is in bed. It seems to me that there is more true Gothic horror in a digestive biscuit, but never mind. Tomorrow I shall be immersed in the comforting sophisticated grandeur of the state capital.

Boston and Harvard Yard

I spend a morning in the city of Boston, ‘Cradle of the Revolution’, filming around the docks where the Boston Tea Party took place and searching (in vain) for Paul Revere’s house. Revere was the patriot and hero whose midnight ride from Boston to Lexington shouting ‘The British are coming!’ is still celebrated in legend and song. The apparent address of his house defeats the taxi’s satellite navigation system and after driving around Boston’s Chinatown asking puzzled citizens for ‘the Revere House’ I find myself in desperate need of a cup of tea.

It so happens that I have heard of a place across the water in Harvard Yard where, almost uniquely in America, a proper cup of tea can be had. If you can pronounce ‘Harvard Yard’ the way the locals do, you can speak Bostonian. It’s more than I can manage – I contrive always to sound Australian when I try. The ‘a’s are almost as short as in ‘cat’, even though they are followed by ‘r’s. Impossible.

Harvard University is America’s Cambridge. So much so that the town it is in, over the water from Boston, is actually called Cambridge.

Those who like good old-fashioned English ‘afternoon tea’, with proper sandwiches and proper cakes, and tea that isn’t the etiolated issue of a bag dangled in warm water, those who like to meet pert young students and trim graduates and twinkly, stylish professors, all congregate gratefully at the weekly teas held by Professor Peter Gomes, theologian, preacher and a natural leader of Harvard society. He dresses like a character from the pages of his favourite author. When asked to offer his list of the Hundred Best Novels in the English Language for one of those millennial surveys in 1999 he lamented, ‘But any such list will always be four short! P.G. Wodehouse only wrote ninety-six books.’

Black, gay, intensely charming, a connoisseur and an anglophile, Gomes is not what you expect of a Baptist minister, a Baptist minister furthermore who (though now a Democrat) was something of a chaplain to the Republican Party, having led prayers at the inaugurations of both Ronald Reagan and George Bush Snr.

‘I was a Republican because my mother was a Republican and her mother before her. That nice President Lincoln who freed the slaves was a Republican and our family chose not to forget that fact.’

The downstairs lavatory in his beautifully furnished house is filled with portraits of Queen Victoria at various stages of her life, from young princess to elderly widow. I emerge from it murmuring praise.

‘Ah, you like my Victoria Station!’ beams Gomes, ‘I’m so happy.’

‘You’re obviously gay,’ I say to him. ‘But some people might be surprised to know that you are also openly black … no, hang on, I’ve got that the wrong way round.’

He bellows with laughter. ‘No, you got it entirely right, you naughty man.’

‘Your command of language, your love of ornament, literature and social style … is that regarded by some as a kind of betrayal?’

‘Someone once called me an Afro-Saxon,’ he says. ‘It was meant as an insult, but I take it as a compliment.’

I am sorry to leave the elegance and charm of Harvard, but there is plenty more elegance and charm awaiting me up ahead in Rhode Island.

RHODE ISLAND (#ulink_8862931c-9971-5696-b21b-0923d18784aa)

KEY FACTS

Abbreviation:

RI

Nickname:

The Ocean State

Capital:

Providence

Flower:

Violet

Tree:

Red maple

Bird:

Rhode Island red chicken

Drink:

Coffee milk

Motto:

Hope

Well-known residents and natives:

General Burnside, Dee Dee Myers, H.P. Lovecraft, S.J. Perelman, Cormac McCarthy, George M. Cohan, Nelson Eddy, Van Johnson, James Woods, the Farelly Brothers, Seth ‘Family Guy’ MacFarlane.

RHODE ISLAND

‘I do not especially mind being asked as a guest onboard a boat, so long as I do not have to do anything more than sip wine.’

Wedged between Massachusetts and Connecticut and very much the smallest state in the union, the anchor on Rhode Island’s seal and its official nickname of the ‘Ocean State’ tell you that they take nautical matters seriously here …

The Cliff Walk

From about the middle of the nineteenth century wealthy plantation families from the South began to build themselves ‘cottages’ along the clifftops of Newport, where they could escape the insufferably humid heat of the Southern summer and enjoy the relatively bracing and comfortable breezes rolling in from the Atlantic. Over the next few decades rich Northern families began to do the same as the Gilded Age of Vanderbilts and Astors reached its imponderably wealthy, stiflingly opulent and dizzyingly powerful zenith. These cottages were in fact vast mansions, some of seventy rooms or more, designed to be lived in for only a few months of the year, but all displaying the incalculable and overwhelming riches and status that the robber barons and industrialists of post-Civil-War America had heaped up in so short a time. Never in the field of human commerce, I think it is fair to say, had so much money been made so fast and by so few.

Today the cliff walk between Bellevue Avenue and the sea is a tourist destination and many of the grander cottages are owned and run, not by their original families, but by the Newport County Preservation Society and other trusts and bodies dedicated to keeping these gigantic fantasies from crumbling away.

There are still some survivors living around Bellevue Avenue, however, and I have tea with one of them, the great Oatsie Charles, a wondrous wicked twinkling grande dame of the old school. The first president she ever met was Franklin D. Roosevelt, she attended the wedding of JFK to Jacqueline Bouvier and her talk is a magnificent tour d’horizon of high-born American family life – Hugh Auchincloss, Doris Duke, Astors, Mellons, Radziwills, parties, disputed wills, feuds, marriages, divorces and scandals:

‘She was a Van Allen, of course, which made all the difference … Bunny Mellon and C.Z. Guest were there naturally … Heaven knows what he saw in her, she can’t have had more than two hundred million which these days … she married the Duke of Marlborough. Calamitous error, we all saw that it would never do …’ All spoken in a luxurious and old-style Alabama accent elegantly mixed with an international rich aristocrat’s amused drawl.

‘I can’t tell you how beautiful even ugly people looked back then.’

‘Was it quite formal?’

‘Well, we dressed for dinner every night and all the houses were formally staffed. Handsome footmen in divine livery. We certainly never saw anyone looking like you …’ Oatsie wrinkles her nose in apparent disgust at the film crew who are dressed in the standard grungey outfit of shorts, t-shirts and sandals. ‘A man’s neck can be a thing of beauty,’ she adds, rather startlingly. ‘And yours,’ she indicates the sound recordist’s, ‘has all the qualities. Even yours, darling,’ she turns to me, ‘though yours is higher than most.’

The tea has turned rapidly to claret, served by a devoted butler, whose duty is also to transport his mistress around her messuage in a golf cart, upon which entirely silly conveyance Oatsie somehow managed to bestow the air and dignity of a fabulous Oriental litter. We go next door to the Big Mansion, for Oatsie now makes do in a converted chauffeur’s house which is big and beautiful enough in its own right, being full of her paintings, furniture and exquisite knick-knacks. ‘Land’s End’, the Big Mansion, built by the novelist Edith Wharton, the supreme chronicler of the Gilded Age, has been given by Oatsie to her daughter Victoria and son-in-law Joe.

A little gilt may have come off the Age and a little guilt may have been added, but from where I stood it was pretty Gilded still.

I am Sailing

Aside from the eye-popping, jaw-dropping, bowel-shattering wealth on display along the cliff walk, there is class of a trimmer, more elegant kind still flourishing in Newport. This is a wonderful place to sail and has been a centre of regattas and races for over a hundred years.

The greatest prize in sailing is of course the America’s Cup, ‘the oldest active trophy in international sport’, the great dream, the Holy Grail – The One. It was offered as a prize by the British Royal Yacht Squadron of Cowes, Isle of Wight in 1851, and was won by a boat called America, which is how the cup gets its name, though it might just as well have been because yachts from the United States have won it so consistently and for so long …

Enormous fortunes have been poured into chasing the cup and for 132 years it remained in America, for much of that time in Newport. Poor Britain, that great sailing nation, has won the trophy precisely zero times. The United States held it for the longest winning streak in history, testament to the remarkable qualities of American seamanship, marine savvy, nautical engineering skills and sheer damned money.

Most would agree that the Golden Age of America’s Cup racing was the late forties, fifties and sixties, the days of the 12-metre class yacht. In 1962, winning by 4–1 and watched by President and Mrs Kennedy, was the graceful Weatherly. She kept the cup in Newport, where it had been since 1930 and where it would remain until Alan Bond of Perth, Australia finally broke that winning streak in 1983. The Weatherly is now one of only three surviving wooden America’s Cup defenders in the world, the only yacht to have won the cup when not newly built. She is beautiful. My, she is yare, as Grace Kelly says about her boat the True Love in the film High Society, which is set, of course, in Rhode Island. The Weatherly is as yare as they come. She is now owned by George Hill and Herb Marshall who manage to keep her in tip-top racing condition and to make money from her by charter.

George, a fit and trim fifty-year-old with silver hair and a lean, outdoors face, watches me clamber aboard, pick myself up, trip over a sticky-up thing that had no right to be there, pick myself up again and fall down in a heap, gasping.

‘Welcome aboard,’ he says.

A crew of three barefoot limber girls and a barefoot limber youth are tying knots with their toes, hauling on winches and, without trying, outdoing Tommy Hilfiger and Ralph Lauren models for looks and style. Within a few minutes sails have been unfurled and ropes uncleated and we are under way. I take up a position next to George, who is manning the wheel and calling out mysterious commands.

This is real sailing, the power, speed and excitement is hard to convey. I have always been a physical coward in sporting endeavours, sailing not excluded. Being shouted at to ‘turn about’, having to duck as great beams swing round to bang you on the head, leaning over precipitately, simply not understanding what is going on, having words like ‘tack’, ‘jib’, ‘sheet’ and ‘cleat’ hurled at you … my childhood was full of such moments, growing up as I did in a nautical county like Norfolk and I long ago decided that sailing was for Other People. I do not especially mind being asked as a guest on board a boat, so long as I do not have to do anything more than sip wine.

George has other ideas. If I am to go on board the Weatherly then I am to pay my way by crewing. He is very kind but very firm on this point as he steps aside for me to steer.

‘You’re luffing,’ he says.

‘Well, more a bark of joy at the blue sky and the crisp …’

‘No, not laughing, luffing. The canvas is flapping. Steer into the wind and keep the sail smooth.’

‘Oh right. Got you.’

George is a proud Rhode Islander. ‘Rhode Island is known to most Americans as a unit of size,’ he says. ‘You hear news stories like “an iceberg broke off Antarctica bigger than the state of Rhode Island” or “So and so’s ranch is bigger than Rhode Island”. Try to come up just a little bit. Once you’re on the breeze like this just little small slow adjustments. That’s good, just there and no higher. The Rhode Island charter of 1663 is an amazing document. It contains all of the concepts of freedom of speech and freedom of religion at a time when – you’re luffing again … when she loads up like that, just straighten her out.’

Strangely I enjoy myself. I enjoy myself very much indeed. I will go further. I have one of the most pleasurable days of the 18,330 or so I have spent thus far on this confusing and beguiling planet. The speed, the precision, the astounding power bewitched me: it was a glorious day, Newport Sound and Narragansett Bay sparkled and shimmered and glittered, the great bridges and landmarks around Newport shone in clean, clear light. You would have to be sullen and curmudgeonly indeed not to be enchanted, intoxicated and thrilled to the soles of your boat-shoes by this fabulous (and fabulously expensive) class of sailing.

Farewell, Rhode Island. Farewell too any lingering belief that America might be a classless society … I luff myself silly at such a thought.

CONNECTICUT (#ulink_ec351138-39c1-552f-9aac-eaf5997a521a)

KEY FACTS

Abbreviation:

CT

Nicknames: