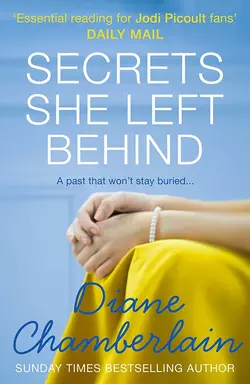

Secrets She Left Behind

Diane Chamberlain

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 150.68 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ‘Essential reading for Jodi Picoult fans’ Daily MailA past that won’t stay buried…Returning home, Maggie hides herself away, too afraid to see Keith, the boy she grew up with, played with as a child – and recently learnt is her half-brother.Keith nearly lost his life in the fire and the emotional and physical wounds he carries have changed him forever. With childhood innocence gone, Maggie and Keith must learn to come to terms with their new lives, but trying to move forward will have deadly consequences…Praise for Diane Chamberlain ‘Fans of Jodi Picoult will delight in this finely tuned family drama, with beautifully drawn characters and a string of twists that will keep you guessing right up to the end.′ – Stylist‘A marvellously gifted author. Every book she writes is a gem’ – Literary Times’Essential reading for Jodi Picoult fans’ Daily Mail’So full of unexpected twists you′ll find yourself wanting to finish it in one sitting. Fans of Jodi Picoult′s style will love how Diane Chamberlain writes.’ – Candis