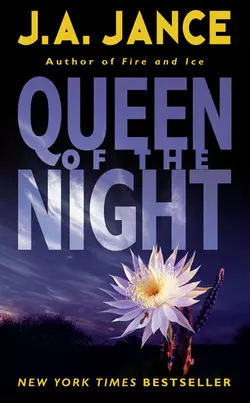

Queen of the Night

J. A. Jance

The New York Times bestselling author brings back the Walker family in a multilayered thriller in which murders past and present connect the lives of three families.Every summer, in an event that is commemorated throughout the Tohono O'odham Nation, the Queen of the Night flower blooms in the Arizona desert. But one couple's intended celebration is shattered by gunfire, the sole witness to the bloodshed a little girl who has lost the only family she's ever known.To her rescue come Dr. Lani Walker, who sees the trauma of her own childhood reflected in her young patient, and Dan Pardee, an Iraq war veteran and member of an unorthodox border patrol unit called the Shadow Wolves. Joined by Pima County homicide investigator Brian Fellows, they must keep the child safe while tracking down a ruthless killer.In a second case, retired homicide detective Brandon Walker is investigating the long unsolved murder of an Arizona State University coed. Now, after nearly half a century of silence, the one person who can shed light on that terrible incident is willing to talk. Meanwhile, Walker's wife, Diana Ladd, is reliving memories of a man whose death continues to haunt her.As these crimes threaten to tear apart three separate families, the stories and traditions of the Tohono O'odham people remain just beneath the surface of the desert, providing illumination to events of both self-sacrifice and unspeakable evil.

Queen of the Night

J. A. Jance

Contents

Cover (#u9275233c-a65f-5381-945c-8f541cb22060)

Title Page (#u1804e550-3c32-557c-b356-6250c77dbe8a)

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Here’s a sneak preview of J. A. Jance’s new novel

About the Author

By J. A. Jance

Copyright

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#u5cf2dd7a-e5e8-5689-906b-74fed521fb3d)

THEY SAY IThappened long ago that a young woman of the Tohono O’odham, the Desert People, fell in love with a Yaqui warrior, a Hiakim, and went to live with him and his people, far to the South. Every evening, her mother, Old White- Haired Woman, would go outside by herself and listen. After a while her daughter’s spirit would speak to her from her new home far away. One day Old White-Haired Woman heard nothing, so she went to find her husband.

“Our daughter is ill,” Old White-Haired Woman told him. “I must go to her.”

“But the Hiakim live far from here,” he said, “and you are a bent old woman. How will you get there?”

“I will ask I’itoi, the Spirit of Goodness, to help me.”

Elder Brother heard the woman’s plea. He sent Coyote, Ban, to guide Old White-Haired Woman’s steps on her long journey, and he sent the Ali Chu Chum O’odham, the Little People—the animals and birds—to help her along the way. When she was thirsty, Ban led her to water. When she was hungry, the Birds, U’u Whig, brought her seeds and beans to eat.

After weeks of traveling, Old White-Haired Woman finally reached the land of the Hiakim. There she learned that her daughter was sick and dying.

“Please take my son home to our people,” Old White-Haired Woman’s daughter begged. “If you don’t, his father’s people will turn him into a warrior.”

You must understand, nawoj, my friend, that from the time the Tohono O’odham emerged from the center of the earth, they have always been a peace-loving people. So one night, when the Hiakim were busy feasting, Old White-Haired Woman loaded the baby into her burden basket and set off for the North. When the Yaqui learned she was gone, they sent a band of warriors after her to bring the baby back.

Old White-Haired Woman walked and walked. She was almost back to the land of the Desert People when the Yaqui warriors spotted her. I’itoi saw she was not going to complete her journey, so he called a flock of shashani, black birds, who flew into the eyes of the Yaqui and blinded them. While the warriors were busy fighting shashani, I’itoi took Old White-Haired Woman into a wash and hid her.

By then the old grandmother was very tired and lame from all her walking and carrying.

“You stay here,” Elder Brother told her. “I will carry the baby back to your people, but while you sit here resting, you will be changed. Because of your bravery, your feet will become roots. Your tired old body will turn into branches. Each year, for one night only, you will become the most beautiful plant on the earth, a flower the Milgahn, the whites, call the night-blooming cereus, the Queen of the Night.”

And it happened just that way. Old White-Haired Woman turned into a plant the Indians call ho’ok-wah’o, which means Witch’s Tongs. But on that one night in early summer when a beautiful scent fills the desert air, the Tohono O’odham know that they are breathing in kok’oi ’uw, Ghost Scent, and they remember a brave old woman who saved her grandson and brought him home.

Each year after that, on the night the flowers bloomed, the Tohono O’odham would gather around while Brought Back Child told the story of his brave grandmother, Old White-Haired Woman, and that, nawoj, my friend, is the same story I have just told you.

San Diego, California

Saturday, March 21, 1959, Midnight

58º Fahrenheit

Long after everyone else had left the beach and returned to the hotel, and long after the bonfire died down to coals, Ursula Brinker sat there in the sand and marveled over what had happened. What she had allowed to happen.

When June Lennox had invited Sully to come along to San Diego for spring break, she had known the moment she said yes that she was saying yes to more than just a fun trip from Tempe, Arizona, to California. The insistent tug had been there all along, for as long as Sully could remember. From the time she was in kindergarten, she had been interested in girls, not boys, and that hadn’t changed. Not later in grade school when the other girls started drooling over boys, and not later in high school, either.

But she had kept the secret. For one thing, she knew how much her parents would disapprove if Sully ever admitted to them or to anyone else what she had long suspected— that she was a lesbian. She didn’t go around advertising it or wearing mannish clothing. People said she was “cute,” and she was—cute and smart and talented. She didn’t know exactly what would happen to her if people figured out who she really was, but it probably wouldn’t be good. She did a good job of keeping up appearances, so no one guessed that the girl who had been valedictorian of her class and who had been voted most likely to succeed was actually queer “as a three-dollar bill.” That was what some of the boys said about people like that—people like her. And she was afraid that by talking about it, what she was feeling right now would be snatched away from her, like a mirage melting into the desert.

She had kept the secret until now. Until today. With June. And she was afraid, if she left the beach and went back to the hotel room with everyone else and spoke about it, if she gave that newfound happiness a name, it might disappear forever as well.

The beach was deserted. When she heard the sand- muffled footsteps behind her, she thought it might be June. But it wasn’t.

“Hello,” she said. “When did you get here?”

He didn’t answer that question. “What you did was wrong,” he said. “Did you think you could keep it a secret? Did you think I wouldn’t find out?”

“It just happened,” she said. “We didn’t mean to hurt you.”

“But you did,” he said. “More than you know.”

He fell on her then. Had anyone been walking past on the beach, they wouldn’t have paid much attention. Just another young couple carried away with necking; people who hadn’t gotten themselves a room, and probably should have.

But in the early hours of that morning, what was happening there by the dwindling fire wasn’t an act of love. It was something else altogether. When the rough embrace finally ended, the man stood up and walked away. He walked into the water and sluiced away the blood.

As for Sully Brinker? She did not walk away. The brainy cheerleader, the girl who had it all—money, brains, and looks—the girl once voted most likely to succeed would not succeed at anything because she was lying dead in the sand—dead at age twenty-one—and her parents’ lives would never be the same.

Los Angeles, California

Saturday, October 28, 1978, 11:20 P.M.

63º Fahrenheit

As the quarrel escalated, four-year-old Danny Pardee cowered in his bed. He covered his head with his pillow and tried not to listen, but the pillow didn’t help. He could still hear the voices raging back and forth: his father’s voice and his mother’s. Turning on the TV set might have helped, but if his father came into the bedroom and found the set on when it wasn’t supposed to be, Danny knew what would happen. First the belt would come off and, after that, the beating.

Danny knew how much that belt hurt, so he lay there and willed himself not to listen. He tried to fill his head with the words to one of the songs he had learned at preschool: “You put your right foot in; you put your right foot out. You put your right foot in, and you shake it all about. You do the hokey-pokey and you turn yourself around. That’s what it’s all about.”

He was about to go on to the second verse when he heard something that sounded like a firecracker—or four firecrackers in a row, even though it wasn’t the Fourth of July.

Blam. Blam. Blam. Blam.

After that there was nothing. No other sound. Not his mother’s voice and not his father’s, either. An eerie silence settled over the house. First it filled Danny’s ears and then his heart.

Finally the bedroom door creaked open. Danny knew his father was standing in the doorway, staring down at him, so he kept both eyes shut—shut but not too tightly shut. That would give it away. He didn’t move. He barely breathed. At last, after the door finally clicked closed, he opened his eyes and let out his breath.

He listened to the silence, welcoming it. The room wasn’t completely dark. Streetlights in the parking lot made the room a hazy gray, and there was a sliver of light under the doorway. Soon that went away. Knowing that his father had probably left to go to a bar and drink some more, Danny was able to relax. As the tension left his body, he fell into a deep sleep, slumbering so peacefully that he never heard the sirens of the arriving cop cars or of the useless ambulance that arrived far too late. Danny had no idea that the gunshot victim, his mother, was dead long before the ambulance got there.

Much later, at least it seemed much later to him, someone—a stranger in a uniform—gently shook him awake. The cop wrapped the tangled sheet around Danny and lifted him from the bed.

“Come on, little guy,” he said huskily. “Let’s get you out of here.”

Thousand Oaks, California

Monday, June 1, 2009, 11:45 P.M.

60º Fahrenheit

It was late, well after eleven, as Jonathan sat in the study of his soon-to-be-former McMansion and stared at his so-called wall of honor. The plaques and citations he saw there—his Manager of the Year award, along with all the others that acknowledged his years of exemplary service, were relics from another time and place—from another life. They were the currency and language of some other existence, where the rules as he had once known them no longer applied.

What had happened on Wall Street had trickled down to Main Street. As a result, his banking career was over. His job was gone. His house would be gone soon, and so would his family. He wasn’t supposed to know about the boyfriend Esther had waiting in the wings, but he did. He also knew what she was really waiting for—the money from his 401(k). She wanted that, too, and she wanted it now.

Esther came in then—barged in, really—without knocking. The fact that he might want a little privacy was as foreign a concept as the paltry career trophies still hanging on his walls. She stood there staring at him, hands on her hips.

“You changed the password on the account,” she said accusingly.

“The account I changed the password on isn’t a joint account,” he told her mildly. “It’s mine.”

“We’re still married,” she pointed out. “What’s yours is mine.”

And, of course, that was the way it had always been. He worked. She stayed home and saw to it that they lived beyond their means, which had been considerable when he’d still had a good job. The problem was he no longer had that job, but she was still living the same way. As far as she was concerned, nothing had changed. For him everything had changed. Esther had gone right on spending money like it was water, but now the well had finally run dry. There was no job and no way to get a job. Banks didn’t like having bankers with overdue bills and credit scores in the basement.

“I signed the form when you asked me to so we could both get the money,” she said. “I want my fair share.”

He knew there was nothing about this that was fair. It was the same stunt his mother had pulled on his father, making him cough up money that she had never earned. Well, maybe the scenario wasn’t exactly the same. As far as he knew, his mother hadn’t screwed around on his father, but Jonathan had vowed it wouldn’t happen to him—would never happen to him. Yet here it was happening—and then some.

“It may be in an individual account, but that money is a joint asset,” Esther declared. “You don’t get to have it all.”

She was screaming at him now. He could hear her and so could anyone else in the neighborhood. He was glad they lived at the end of the cul-de-sac—with previously foreclosed houses on either side. It was a neighborhood where living beyond your means went with the territory.

“By the time my lawyer finishes wiping the floor with you, you’ll be lucky to be living in a homeless shelter,” she added. “As for seeing the kids? Forget about it. That’s not going to happen. I’ll see to it.”

With that, she spun around as if to leave. Then, changing her mind, she grabbed the closest thing she could reach, which turned out to be the wooden plaque with the bronze Manager of the Year faceplate, and heaved it at him. The sharp corner of the wood caught him full in the forehead—well, part of his very tall comb-over forehead—and it hurt like hell. It bled like hell.

As blood leaked into his eye and ran down his cheek, all the things he had stifled through the years came to a head. He had reached the end of his rope, the point beyond which he had nothing left to lose.

Opening the top drawer of his desk, he removed the gun—a gun he had purchased with every intention of turning it on himself. Then, rising to his feet, he hurried out of the room, intent on using it on someone else.

His whole body sizzled in a fit of unreasoning hatred. If that had been all there was to it, any defense attorney worthy of the name could have gotten him off on a plea of temporary insanity, because in that moment he was insane—legally insane. He knew nothing about the difference between right and wrong. All he knew was that he had taken all he could take. More than he could take.

The difficulty is that this was only the start of Jonathan Southard’s problems. Everything that happened after that was entirely premeditated.

Chapter 1 (#u5cf2dd7a-e5e8-5689-906b-74fed521fb3d)

Tucson, Arizona

Saturday, June 6, 2009, 8:00 A.M.

76º Fahrenheit

PIMA COUNTY HOMICIDE detective Brian Fellows loved Saturdays, even hot summer Saturdays. Kath, Brian’s wife, usually worked Saturday shifts at her Border Patrol desk job, which meant Brian had the whole day to spend with his girls, six-year-old twins Annie and Amy. They usually started with breakfast, either sharing a plate-sized sticky sweet roll at Gus Balon’s on Twenty-second Street, or downing eye-watering plates of chorizo and eggs at Wag’s on Grant.

After that, they went home to clean house. Brian’s mother had been a much-divorced scatterbrain even before she became an invalid. Brian had learned from an early age that if he wanted a clean house, he’d be the one doing it. It hadn’t killed him, either. He’d turned into a self-sufficient kind of guy and, according to Kath, an excellent catch for a husband.

Brian wanted the same thing for his daughters—for them to be self-sufficient. It didn’t take long on Saturdays to whip their central-area bungalow into shape. In the process, while settling the occasional squabble, being a bit of a tough taskmaster, and hearing about what was going on with the girls, Brian made sure he was a real presence in his daughters’ lives—a real father.

That was something that had been missing in Brian’s childhood—at least as far as his biological father was concerned. His “sperm donor,” as Brian thought of the man who had been MIA in his life from before he was born. He wouldn’t have had any idea about what fathers were supposed to be or do if it hadn’t been for Brandon Walker, his mother’s first husband and the father of Tommy and Quentin, Brian’s older half brothers.

After Brian’s mother’s first divorce, Brandon Walker, then a Pima County homicide detective, had come to the house each weekend and dutifully collected his own sons to take them on noncustodial outings. One of Brian’s first memories was of being left alone on the front steps while Quentin and Tommy went racing off to jump in their father’s car to go somewhere fun—to a movie or the Pima County Fair, or maybe even the Tucson Rodeo—while Brian, bored and lonely, had to fend for himself.

Then one day a miracle happened. After Quentin and Tommy were already in the car, Brandon had gotten back out. He came up the walk and asked Brian if he would like to go along. Brian was beyond excited. Quentin and Tommy had been appalled and had done everything in their power to make Brian miserable, but they did that anyway—even before Brandon had taken pity on him.

From then on, that’s how it was. Whenever Brandon had taken his own boys somewhere, he had taken Brian as well. The man had become a superhero in Brian’s eyes. He had grown up wanting to be just like him, and it was due in no small measure to Brandon Walker’s early kindness that Brian Fellows was the man he was today—a doting father and an experienced cop. And it was why, on Saturday afternoons, after the house was clean, that he never failed to take his girls somewhere to do something fun—to the Randolph Park Zoo or the Arizona Sonora Desert Museum. Today, as hot as it was, they had already settled on going to a movie at Park Mall.

Brian was on call. Only if someone decided to kill someone tonight would he have to go in to work. Otherwise he would have had his special day with his girls— well, all but one of his girls. That was what made life worth living.

Tucson, Arizona

Saturday, June 6, 2009, 11:00 A.M.

90º Fahrenheit

Brandon Walker knew he was running away. He had the excuse of running to something, but he understood that he was really escaping from something else, something he didn’t want to face. He would face it eventually because he had to, but not yet. He wasn’t ready.

Not that going to see G. T. Farrell was light duty by any means. Stopping by to see someone who was on his way to hospice care wasn’t Brandon’s idea of fun. Sue, Geet’s wife, had called with the bad news. Her husband’s lung cancer had been held at bay for far longer than anyone had thought possible, but now it was back. And winning.

“He’s got a set of files that he had me bring out of storage,” Sue had said in her phone call. “He made me promise that I’d see to it that you got them—you and nobody else.”

Brandon didn’t have to ask which file because he already knew. Every homicide cop has a case like that, the one that haunts him and won’t let him go, the one where the bad guy got away with murder. For Geet Farrell that case had always been the 1959 murder of Ursula Brinker, a twenty-one-year-old coed who had died while on a spring-break trip to San Diego.

Geet had been a newbie ASU campus cop at the time of her death. Even though the crime had occurred in California, it had rocked the entire university community. Geet had been involved in interviewing Ursula’s friends and relations, including her grieving parents. The case had stayed with him, haunting him the whole time he’d worked as a homicide detective for the Pinal County Sheriff’s Department, and through his years of retirement as well. Now that Geet knew it was curtains for him, he wanted to hand Ursula’s unsolved case off to someone else and let his problem be Brandon’s problem.

Fair enough, Brandon thought. If I’m dealing with Geet Farrell’s difficulties, I won’t have to face up to my own.

Geet was a good five years older than Brandon. They had met for the first time as fellow cops decades earlier. In 1975, Brandon Walker had been working Homicide for the Pima County Sheriff’s Department, and G. T. Farrell had been his Homicide counterpart in neighboring Pinal. Between them they had helped bring down a serial killer named Andrew Philip Carlisle. Partially due to their efforts, Carlisle had been sentenced to life in prison. He had lived out his remaining years in the state prison in Florence, Arizona, where he had finally died.

Brandon Walker had also received a lifelong sentence as a result of that case, only his had been much different. One of Carlisle’s intended victims, the fiercely independent Diana Ladd, had gone against type and consented to become Brandon Walker’s wife. They had been married now for thirty-plus years.

It was hard for Brandon to imagine what his life would have been like if Andrew Carlisle had succeeded in murdering Diana. How would he have survived for all those years if he hadn’t been married to that amazing woman? How would he have existed without Diana and all the complications she had brought into his life, including her son, Davy, and their adopted Tohono O’odham daughter, Lani?

Much later, long after both detectives had been turned out to pasture by their respective law enforcement agencies, Geet by retiring and Brandon by losing a bid for re-election, Geet had been instrumental in the creation of an independent cold case investigative entity called TLC, The Last Chance, an organization founded and funded by Hedda Brinker, Ursula Brinker’s still grieving mother. In an act of seeming charity, Geet had seen to it that his old buddy, former Pima County sheriff Brandon Walker, be invited to sign on with TLC.

That ego-salving invitation, delivered in person by a smooth-talking attorney named Ralph Ames, had come at a time when, as Brandon liked to put it, he had been lower than a snake’s vest pocket. He had accepted Ames’s offer without a moment of hesitation. In the intervening years, Brandon had worked hand in hand with other retired law enforcement and forensic folks who volunteered their skills and expertise to make TLC live up to its case-closing promises. For Brandon, the ability to do that—to continue making a contribution even in retirement—had saved his sanity, if not his life.

All of which meant Brandon owed everything to Geet Farrell. That was why he was making this pilgrimage to Casa Grande late in the morning on what promised to be a scorcher of a Saturday in early June. Of course heat was relative. By July and early August, the hot days of June would seem downright cool in comparison.

Weather aside, Brandon understood that this was going to be a deathbed visit, but he didn’t mind. He hoped that by doing whatever he could to help out, he might be able to even the score with Geet Farrell just a little. After all, this was a debt of gratitude, one Brandon Walker was honor-bound to repay.

Tucson, Arizona

Saturday, June 6, 2009, 1:10 P.M.

94º Fahrenheit

Diana Ladd Walker sat in her backyard gazebo next to a bubbling fountain typing into her laptop. It was shady there, but it was still hot and dry. Soon she’d either have to go into the pool for a dip, or else she’d have to retreat to the air-conditioned comfort of the house.

“So how are things working out for you?” Andrew Carlisle asked.

Rendered speechless, Diana stared at the vision that had suddenly materialized over the top of her computer.

Shirtless and hatless, Carlisle sat in full early-afternoon sunlight with his scarred face and sightless eyes staring up into a blazing blue sky. If he hadn’t been blind already, staring at the sun would have made him so.

Examining every aspect of her unwelcome visitor, Diana might have been viewing a close-up shot of someone on Brandon’s new high-defflat-screen TV set. Every detail was astonishingly vivid—from the sparse strands of white hair that sprinkled his sunken chest to the grizzled unshaved beard that dotted his gaunt cheeks and the scarred and rippled skin of his forehead and nose.

I did that, Diana thought, gasping involuntarily at the sight of those horrifying scars. I’m responsible for doing that to a living, breathing human being, back when he was alive.

Which Andrew Carlisle was not. The man sitting across the table from Diana was most definitely not alive. She knew that for certain. He had been alive when he had come to her house years earlier, intent on rape and murder. Before it was over, he had left Diana with his own special trademark—a fierce bite mark that even now still scarred her breast. But Carlisle had underestimated her back then. He hadn’t expected Diana to fight back or to leave him permanently disfigured in the process. All of that had happened long ago—before he had gone to prison for the second time and before he died there. Back in those days there had been no swimming pool or fountain or gazebo in Diana’s walled backyard, and she most certainly hadn’t been working on a laptop.

“We are not having this conversation,” she said to him now.

“Come on, Diana,” he urged. “For old times’ sake. Let bygones be bygones. Tell me, how’s the writing going? What are you working on now?”

She was dealing with some backed-up business correspondence, but she wasn’t going to tell him that.

“What I’m working on is none of your business,” she responded.

“Of course it’s my business,” Carlisle insisted. “I’m always interested when one of my students goes on to achieve remarkable success in the publishing world.”

“I was not your student,” Diana told him flatly. “My first husband was your student, remember? I never was. Go away and leave me alone.”

“Give me a break, Diana. I’m still annoyed that Shadow of Death won a Pulitzer. You never would have won that award without me. I was the guy who came up with the idea, and the whole book was all about me. You should have given me more credit.”

“You didn’t deserve more credit,” she said. “You didn’t write it. I did.”

“Oh, well. No matter,” he said with a sigh. “After all, fame is fleeting. I thought you’d be glad to see me. Mitch may drop by a little later, too. And Gary. You’d like to see him again, too, wouldn’t you? Although, come to think of it, maybe not. That self-inflicted bullet left a hell of a hole in his head. Not so much in the front as in the back. Exit-wound damage and all that. I’m sure you know how those work.”

Living or dead, Diana had no desire to see her dead first husband, Garrison Walther Ladd III, nor did she want to see Mitch Johnson, the surrogate killer Carlisle had sent to attack her family in his stead when Carlisle himself could no longer pose a direct threat.

“Shut up,” she said.

Tires crunched on the gravel driveway. Damsel, Diana’s aging nine-year-old mutt, pricked her ears and raised her head at the sound. She had come to Diana and Brandon as a rollicking pound puppy some eight years earlier when her antics had earned her the title of Damn Dog. Now she was a well-behaved grizzled old dog with a nearly white muzzle and a game hip. She stood up and steadied herself for a moment. Then, with an arthritic limp, she hurried over to the side gate, barking in welcome.

“My daughter’s coming,” Diana said. “Go away.”

“Lani is coming here?” Carlisle sounded delighted. “The lovely Lani? Do tell. Wonderful. Maybe she’ll show me her scar.”

“What scar?”

“Oh, I forgot. You don’t know about that.”

“What scar?” Diana insisted.

“Ask her about it if you don’t believe me. I understand Mitch left her a little something to remember him by. Let’s just say it’s a token of my esteem.”

Lani had been sixteen when Mitch Johnson, Andrew Carlisle’s minion, had kidnapped Diana’s daughter.

“What?” Diana asked. “What did he do to her?”

“Why don’t you ask her yourself?” Determinedly, Diana turned her attention back to her laptop. She thought Carlisle would disappear when she did that, but he didn’t. He stayed right there with his face turned in her direction. Since he was blind now, he could no longer stare at her, but the same expression was on his face—the same disparaging smirk he had aimed at her once before, long ago in a courthouse hallway.

“You’re not welcome here,” she told him. “Go away.”

Highway 86, West of Tucson, Arizona

Saturday, June 6, 2009, 12:00 P.M.

93º Fahrenheit

Eight-year-old Gabriel Ortiz sat up straight in Dr. Lani Walker’s car and seemed to be studying the scenery as it whizzed by outside the windows of the speeding Passat. This was the first time Lani could remember his being tall enough to ride in the front seat. He evidently liked it.

“Where are we going again, Lani Dahd?” he asked.

Dahd was Tohono O’odham for godmother, and that was Lani Walker’s role in Gabe’s young life. She had been there to deliver him in the back of her adoptive mother’s prized Invicta convertible eight years earlier, and she had been there for him ever since, spending as much time with him as possible whenever she was home on breaks—first from medical school and later from her hospital residency in Denver.

She was doing her best to be Gabe’s mentor and to give him the benefit of everything she had learned from the mentors in her life, her own godparents, namely Gabe’s great-aunt, Rita Antone, and his grandfather, Fat Crack Ortiz. Of course, those people in turn had learned what they knew from the old people in their own lives, from a blind medicine man called Looks at Nothing, and from Rita’s grand-mother, Oks Amachuda, Understanding Woman.

“We’re going to stop by the house to pick up my mother,” Lani answered. “Then we’re going to a place called Tohono Chul.”

Gabe frowned. “Desert corner?” he asked.

Lani smiled at his correct translation. She was glad he was learning some of his native language, and not just from her, either.

“Not a corner, really,” she corrected. “It’s a botanical garden, devoted to preserving the desert’s native plants.”

“You mean like a zoo but for plants?” Gabe asked.

Lani nodded. “Exactly. There’s a party there tonight. My mother and I are invited, and I thought you should go, too. After all, you’re eight—that’s old enough.”

“What kind of party?” Gabriel asked. “You mean like a birthday party with candles?”

“More like a feast than a birthday party, but with no dancing,” Lani explained.

Gabe shook his head. A feast with no dancing clearly made no sense to him.

“There may be candles,” Lani added, “but they won’t be on a cake. People will be carrying candles around with them so they’ll be able to see in the dark.”

“Why not use flashlights?” he asked.

Lani smiled to herself. Gabe was nothing if not practical. From his perspective, flashlights made more sense than candles. Gabe wanted light, not atmosphere.

“Candles make for a better mood,” she said. Lani waited while Gabe internalized her response. After eight years, Lani was accustomed to answering the boy’s questions, and she did so patiently enough. That was a godmother’s job. As for Gabe’s parents? His father, Leo, was too busy running the family auto repair business, and his mother, Delia Cachora Ortiz, was too busy being the tribal chairman to take time out to provide thoughtful answers to Gabe’s perpetually complicated questions.

Besides, truth be known, Gabe’s city-raised mother probably didn’t know most of those answers herself anyway, at least not the traditional ones—the old ones— Gabe was searching for, the ones he wanted to understand. Delia could probably do a credible job of reciting the meteorological reasons for hot summer days like today when the horizon was dotted with fast-moving whirlwinds, but she didn’t know the vivid stories of Wind-man and Cloud-man, who were the mysterious Tohono O’odham movers and shakers, the entities who stood behind those dancing whirlwinds. Little Gabe Ortiz was always searching for the wisdom and the teachings of the old ways, and those were the ones Lani Walker provided.

“Will there be other Indians there?” Gabe asked now.

“Probably not.”

“Only Anglos and us?”

“Yes.”

“But why?”

That was by far Gabe’s favorite question—the one for all seasons and all reasons. “But why does the ocotillo turn green when it rains? But why do rattlesnakes shed their skin? But why does I’itoi live on Ioligam? But why does it thunder when it rains? But why did my grandfather have to die before I was born? But why? But why? But why?”

Although Gabe’s parents were often too preoccupied to answer the curious little boy’s constant questions, Lani never was. He reminded her of Elephant’s Child in that old Rudyard Kipling story, where the baby elephant was forever asking questions of everyone within hearing distance. Gabe, too, was full of “satiable curiosity,” just as Lani had been when she was a child. She, far more than either of Gabe’s parents, understood how and why those questions needed to be answered, just as Nana Dahd and Fat Crack Ortiz had patiently answered those same questions for her.

“Because Tohono Chul is in Tucson,” Lani said firmly. “Not that many Indians live in Tucson these days.”

“Rita used to live in Tucson,” Gabe responded wistfully. “Now she lives with us. Not with us really. She lives next door.”

For a moment Lani thought he was referring to that other Rita, to Lani’s Rita, to Rita Antone, Nana Dahd, the wrinkled old Indian woman who had been godmother to Lani in the same way Lani was godmother to Gabe. Eventually she realized Gabe was referring to his thirteen-year-old cousin Rita Gomez. That Rita, sometimes called Baby Rita, had been named after her great-aunt, Rita Antone, who was Gabe’s great-aunt as well.

There was silence in the car for the next several minutes as Lani considered how the threads of the Ortiz family had frayed, drawn apart, and then seamlessly repaired themselves.

Charlotte Ortiz Gomez, Gabe’s auntie and Baby Rita’s mother, had been estranged from Gabe’s grandparents, Fat Crack and Wanda Ortiz, for a number of years. During that time Charlotte had lived in Tucson with her jerk of a husband and her daughter. When Fat Crack died, Charlotte had adamantly refused to come to the reservation, not even for her own father’s funeral.

A year or so later, however, when Charlotte’s marriage had ended in divorce, she had come crawling back to the reservation, begging forgiveness. She and Baby Rita had moved into her widowed mother’s mobile home in the Ortiz family compound behind the gas station, where Charlotte had looked after her mother until Wanda’s death two years ago.

“Well?” Gabe prompted. “If there won’t be any Indians there, why do we have to go?”

“Because the Milgahn who are coming tonight want to hear the legend of Old White-Haired Woman,” Lani answered. “Tonight is the one night a year when the night-blooming cereus blossom all over the desert. They have a lot of those plants at Tohono Chul and a lot of people will come to see them. I promised the lady who organizes the party that I would come there to tell the story of Old White-Haired Woman.”

Gabe’s jaw dropped. “But you can’t,” he objected.

It was Lani’s turn to ask. “Can’t what?”

“You can’t tell that story,” Gabe replied. “It’s an I’itoi story,” he added earnestly, “a winter-telling tale. The snakes and lizards are already out. If you tell that story now and one of them hears you, they could hurt you.”

Lani had once asked Gabe’s grandfather, Fat Crack Ortiz, about that very same thing. The old medicine man had been invited to come to a party just like this one for the same reason—to deliver the story at Tohono Chul in honor of that year’s blooms.

“When they asked me to come, I wondered about that,” he said. “So I took the invitation they sent me, I rolled some sacred tobacco, some wiw, and I performed a wustana. By blowing the sacred smoke over the invitation, I knew what I should do.”

“And what was that?” Lani had asked.

“Some of the people have forgotten all about Old White-Haired Woman,” Fat Crack had told her. “Yes, the I’itoi stories are supposed to be winter-telling tales, but on this one night, I’itoi himself doesn’t object to having that story told.”

“The snakes and lizards won’t hurt me,” Lani told Gabe now. “I’itoi doesn’t mind if the story is told on the night the flowers bloom. It’s a good story. People need to remember.”

Tucson, Arizona

Saturday, June 6, 2009, 1:00 P.M.

93º Fahrenheit

“Your hair looks great,” Nicole said, looking up at Abigail Tennant over the bubbling pedicure bath. “Is this a special occasion?”

Abby nodded. “Our anniversary,” she said. “Jack and I met five years ago today. He’s the best thing that ever happened to me.”

“Where’s he taking you?”

“I have no idea,” she said. “It’s a surprise.”

“Someplace good, I hope?” Nicole asked.

“It better be,” Abby answered with a smile. “This will be the first night-blooming cereus party I’ve missed in fifteen years.”

When the manicure/pedicure appointment ended, Abby took her time leaving Hush. Not wanting to chip her polish, she waited an extra twenty minutes before making her way out to the parking lot. When she arrived two hours earlier, she had lucked out and found a bit of shade under a mesquite tree. She unlocked the old Mark VIII with its push-button door code and found the temperature inside was hot, but not nearly as hot as it would have been without the shade augmented by the fold-up reflecting sunscreen she had placed on the inside of the windshield.

The car had been beautiful and sporty when she bought it new fifteen years earlier and days before she set off for her new life in Arizona. She had lived through a brutal divorce in Ohio. After thirty years of marriage, Hank Southard had seen fit to trade Abby in on a much younger model, a woman named DeeAnn who was barely half his age and extremely pregnant by the time Hank and Abby’s divorce was finalized. Two days later Hank had trotted off to Nevada where he had made an honest woman of his mistress by way of a quickie Las Vegas wedding.

Abby had never been able to understand how her son, Jonathan, could have come to the completely illogical conclusion that the divorce was all Abby’s fault; that she had, through some action of her own, been the cause of Hank’s betrayal. Because Jonathan was an adult by then, it hadn’t been a question of custody but a question of loyalty, and Jonathan had stuck with his philandering father.

“Sounds like he was just following the money” was the uncompromising way Jack had explained it to Abby some time later. “Kids are like that. They know which side their bread is buttered on. Hank’s pockets probably looked a lot deeper to Jonathan than yours did. Maybe he’ll wise up someday.”

So far that hadn’t happened, but that ego-damaging time was far enough in the past that it no longer hurt Abby quite so much. When she thought about it now, it seemed like someone else’s ancient history.

For one thing, Abby was an entirely different person than she had been then. After being a stay-at-home mom and a dutiful corporate wife for all those years, she had been devastated by the divorce. It had been that much worse when her former husband, his new wife, and their new baby had settled down in a Columbus neighborhood not far from where she and Hank had lived for much of their married lives. In fact their love nest was close enough to Abby’s home that they had occasionally run into people who had been friends of Hank’s and Abby’s back before the divorce. Those supposedly good friends had never failed to mention to Abby that they had run into Hank and DeeAnn buying groceries at Kroger’s or flats of annuals at Lowe’s.

It wasn’t long before Abby found herself stressing that every time she left the house for any reason, she might come around a corner in the grocery store and stumble into them.

She finally decided she had two choices. She could become a recluse and never leave the house again or she could make a change—a drastic change. It took a while, but eventually that’s what Abby did—she bailed. She had heard about Tucson, had read about Tucson. She had come here on a wing and a prayer with few friends and fewer preconceived notions, determined to start over. And she had.

Jack’s comment about following the money notwithstanding, Abby was fairly well fixed. Thanks to the efforts of an amazingly tough and capable divorce attorney, she’d come away from the marriage in reasonably good financial shape. Abby had invested years of her life supporting Hank’s career, and she deserved every penny of whatever settlement came her way. When it was time for Abby to leave town, the divorce settlement had made it possible for her to put Hank and DeeAnn and her previous life in her rearview mirror. Taking a page from Hank’s playbook, Abby decided it would be a brand-new rearview mirror.

Without consulting anyone, she had driven her stodgy old silver Town Car over to the nearest Lincoln dealer, where she had traded it in on the metallic-green Lincoln Mark VIII. She hadn’t agonized over the deal. She hadn’t spent hours in painful negotiations with first the salesman and later the sales manager the way Hank always used to do, making a war out of trying to work the dealership down to the very lowest price. Abby had spotted the make, model, and color she wanted parked on the showroom floor. She had asked the salesman to bring it out so she could test-drive it, and she had driven away with it signed, sealed, and delivered less than two hours later.

Fifteen years after that purchase, the Mark VIII’s metallic-green paint was starting to deteriorate in Tucson’s unrelenting sun—even though the vehicle spent most days and nights safely stowed in a garage and out of direct sunlight. Much to her satisfaction, however, the vehicle still ran perfectly . . . well, almost perfectly. It had less than 25,000 miles on the odometer. It was one of those cars about which one could truly say, “one-owner vehicle—driven to church and museums.” Because that’s mostly where she drove it—to church, to the grocery stores, and to Tohono Chul, a Tucson botanical garden where Abby was a faithful volunteer.

As for Hank? Unfortunately for him, Danielle, the headstrong daughter he had fathered with his new wife, apparently took after her mother, and not necessarily in a good way. She was gorgeous but dumb as a stump. Halfway through high school, her GPA was so low that acceptance at even a third-rate college was questionable. Hank had always been brainy. So had his only son, Jonathan. Hank had zero patience with people who weren’t as smart as he was. Abby understood better than anyone that having to deal with an intellectually deficient off-spring would be driving the man nuts.

Abby still had friends in Columbus, the same ones who, in the old days, had been only too happy to carry tales to her about what Hank and DeeAnn were up to. Now the tables were turned, and those same friends were still happy to carry tales.

It was through them that Abby had heard that her son, Jonathan, Esther (the wife Abby had never met), and the two grandkids she had never seen were living somewhere in the L.A. area, where he worked for a bank. It was also through those same friends that Abby had learned about Danielle Southard’s dismal academic record, which had resulted in her being dropped from the varsity cheerleading squad. There had also been a huge brouhaha when Danielle and several other girls were picked up for shoplifting during what was supposedly a chaperoned sleepover.

Abby had eagerly gobbled up the morsels of news about JonJon, as she still thought of her son. As for Danielle’s unfortunate missteps? Abby tended to gloat a bit about those. She couldn’t help it.

Hank’s getting his just deserts, Abby thought. He’s stuck dealing with a dim-bulb angst-driven teenager with issues. All I have to worry about is having my Mark VIII repainted. Such a deal. Seems fair to me.

Chapter 2 (#u5cf2dd7a-e5e8-5689-906b-74fed521fb3d)

Tucson, Arizona

Saturday, June 6, 2009, 6:00 A.M.

69º Fahrenheit

AS JONATHAN SOUTHARD sat in the car, watching and waiting, he was amazed at how cold it had been overnight out here in what was supposed to be the desert, and also at how much his arm hurt. It was feverish and throbbing. That was worrisome.

At the time, it hadn’t seemed like that big a deal. Only a little bite, not a big one. That worthless damn dog had never liked him. As far as he was concerned, the feeling was mutual. Major was Esther’s dog—the kids’ dog. It seemed to him that the beagle was beyond dim, but as stupid as the dog had always seemed, that night Major had somehow read his mind and known what was going to happen. How could that be? It seemed weird.

Esther wouldn’t have had a clue that he had come into the room behind her if the dog hadn’t warned her, springing at him from the back of the couch, growling and with his teeth bared. The ferocity of the unexpected attack had forced Jonathan to dodge away and take a step backward. Major had nailed his wrist before he got quite out of reach, drawing blood and knocking the gun from his hand.

When Esther turned around, she didn’t see the weapon. All she saw was her husband. “No!” she yelled at Major. “Come here!”

The dog listened to her and paused for a moment—a moment that allowed Jonathan to retrieve the gun. Naturally he had shot Major first. Then he shot Esther. Once he could hear again, once his ears stopped reverberating, he stood there with the gun still in his bleeding hand and listened, afraid the kids would wake up and come running to see what had happened.

In all honesty, that was the first time he even thought of the kids. What about them? He could call the cops and turn himself in, but what would happen to Timmy and Suzy then? He seemed to remember setting up a guardianship thing so that if something happened to Esther and him together, the kids would go first to Esther’s sister, Corrine. But what would their lives be like if their mother was dead and their father was in prison for killing her? That might even be worse than growing up as Abby Southard’s no-good, worthless son.

He had decided the next step in that instant. If Timmy and Suzy died in their sleep, he could spare them all that suffering—the suffering of living. And that’s what he did—he shot them while they slept, one bullet each. That way they would never have to wonder if their parents loved them. Then he closed their bedroom doors and left them there. As long as the doors were shut—as long as he didn’t venture back into the living room where Esther lay sprawled on the couch, he didn’t have to remember that they were dead. As far as Jonathan was concerned, they were just sleeping.

He went into the bathroom then and collected the whole set of medication bottles Esther kept there. Antidepressants, sleep aids; whatever bottles he could find that said “Do Not Use with Alcohol.” You name it; Esther had it. He took them down to his study along with a bottle of single-malt Scotch.

He poured a full glass, but sat there thinking before he swallowed that first pill. He remembered seeing a movie called The Bucket List, the one about making sure you did all the things you wanted to do before you died.

He decided right then and there that he would go out with a bang, not the way he had left the bank, slinking out after everyone else had left for the night, carrying the personal possessions from his office in a single disgraceful cardboard box.

Hoping to prove his mother’s dire predictions wrong, he had spent his adult life doing what he was supposed to do all this time, twenty-four/seven. Now he was going to do some of the things he wasn’t supposed to do. He closed the open pill bottles. Then he showered and dressed, packed a suitcase with a week’s worth of clothes, and tossed the collection of pill bottles into the mix. The last thing he did before he walked out the door was set the thermostat down to 65 degrees. Who cared if he ran up the electricity bill? He wouldn’t be the one paying it.

Now, five days later and over five hundred miles away, he sat waiting on a residential street in Tucson, Arizona. He’d been doing that for hours now, shifting periodically in the seat, trying to find a comfortable place to rest his throbbing arm. Then, just when he thought he’d maybe go back to the Circle K and pick up some coffee and take a leak, the garage door on the house he was watching slid open.

As the Lexus backed out into the driveway, Jonathan recognized the guy at the wheel as the man he assumed to be Jack Tennant, Abby’s husband. Jonathan never referred to her as Mother. He refused to give her that much credit. While he watched, Jack loaded a golf pullcart and a bag of clubs into the car. That was interesting. If Jack was going to go play golf, Jonathan wanted to know where he was going, how long he’d be gone, and when he’d be back. That’s what these recon trips were all about—getting the lay of the land.

When Jack headed down the street, Jonathan followed. It was as easy as that.

Tucson, Arizona

Saturday, June 6, 2009, 12:00 P.M.

93º Fahrenheit

The dream came while Daniel James Pardee was sleeping. In it he was back in Iraq, riding in the Humvee with Bozo, the dog no one else would take, sitting between him and the driver. As in real life, the driver was none too happy when Bozo, panting and grinning that weird doggy grin of his, had scrambled his hundred-plus pounds of dusty German shepherd into the cab along with Dan.

“Oh, jeez!” the driver muttered. “Not him again. That stinking dog’s so stupid he’d rather chase birds than bad guys.”

That was the reason the dog, formerly known as King and now jeeringly referred to as Bozo the Clown, had been passed along to the newest guy in the unit, Corporal Dan Pardee. “Three’s the charm,” the CO in Mosul had told Dan. “Either Bozo wakes up and gets serious about his job, or he’s out of here.”

Dan understood at once that, in military parlance, “out of here” didn’t mean some nice doggy retirement program somewhere. It meant termination. Period. Bozo’s career with the U.S. Army would be over and so would he.

“Yeah, Justin,” Dan told Corporal Justin Clifford, the driver. “You don’t smell so good yourself, so leave Bozo the hell alone. Let’s get moving.”

In the dream Dan knew Justin’s name. In real life he hadn’t known his name until after “the incident” and until after the wounded driver had been shipped out of theater, first to Germany and then to Walter Reed, suffering from second-and third-degree burns over fifty percent of his body. Both in the dream and in real life, however, the Humvee ground into gear and moved to the head of the supply convoy.

The whole thing went to hell about forty-five minutes later when the world exploded just outside the driver’s window. Blinded by smoke and deafened by the concussion, Dan and Bozo had scrambled out through the door on the Humvee’s relatively undamaged passenger side. When Dan’s hearing returned, the only sound he heard were the agonized screams coming from Corporal Clifford, who was still trapped inside the burning vehicle. Dan was turning back to reach for Clifford and try to pull him out when he saw the insurgent.

It was ironic that that was the word news broadcasters always used to refer to the bad guys—insurgents. Dan often wondered what people back home in the U.S. thought that word meant. They probably figured a group of “insurgents” would be made up of hardened old soldiers, believers in the old ways, who would rather die than vote in a free election.

Not true. This one, the guy materializing like a ghost out of the smoke and dust with an AK-47 in his hands, wasn’t old at all. He was a kid—eleven or twelve at most. Whoever had planted the bomb had left this little shit behind, armed to the teeth and lying in wait hoping to ambush anyone who managed to stagger out of the burning wreckage.

Both in real life and in the dream, things slowed down at that point. Corporal Daniel Pardee was faced with two impossible choices. Should he reach inside and try to rescue poor Justin Clifford, or should he leave the other man to die and reach for his M16?

Before he had a chance to do either one, Bozo decided for them both. He slammed into the gun-toting kid from one side, blindsiding him and hitting him with more than a hundred pounds of biting, snapping fury. The kid was knocked to the ground, screeching, while the gun, now useless, went spinning away out of reach.

The whole thing took only a moment. With the kid and his gun out of the equation, Dan turned his full attention back on Clifford. With almost superhuman strength he had managed to haul the injured driver to relative safety. By then, other troops from the convoy were hurrying forward to offer assistance. It took three of them to haul Bozo off the kid and keep the dog from killing him.

When Dan finally got back to the dog, both in the dream and in real life, he was sitting there, panting and grinning that stupid grin of his, except by then the dog’s happy grin didn’t seem nearly so stupid. Dan had stumbled over to him and gratefully buried his face and hands in Bozo’s dusty, smoky fur. It was only when the hand came away bloodied that Dan realized the dog—his dog—had been cut by shrapnel from the explosion, by flying bits of burning metal and shattered glass. Later on Dan figured out that he’d been cut and burned, too. Both of them had been treated for relatively minor injuries, but Dan knew full well that if it hadn’t been for Bozo— that wonderfully zany Bozo—Justin Clifford would have died that day in Mosul.

At that moment, as if on cue, Dan’s dream ended the same way the firefight had ended—with Bozo. The dog scrambled up onto the bed, whining and licking Dan’s face.

“Go away,” Dan ordered. “Leave me alone.”

From the moment the bomb went off, Bozo was transformed. When it came time to go on patrol, he was dead serious. He paid attention. He obeyed orders. And he seemed to develop almost a sixth sense about the possibility of danger. Twice he had alerted Dan in time for the two of them to dive for cover before bombs exploded rather than after. And if Bozo said someplace was a no-go, Dan paid attention and didn’t go there.

But right now, the dog and the man weren’t working. They were in bed. Bozo immediately understood that his master didn’t mean it, that his order to go away was one that could be disobeyed. As a consequence, he paid no attention and didn’t let up.

The recurring dream came to Dan night after night, or, as now when he was working the night shift, day after day. The nightmare always left him shaken and anxious and drenched in sweat. He wondered if maybe he had cried out in his sleep and that was what caused Bozo to come running.

Dan tried unsuccessfully to dodge away from Bozo by pulling the sweat-soaked covers over his head and turning the other way, but Bozo was relentless. Thumping his tail happily, the dog scrambled to Dan’s other side and burrowed under the covers to join him. After all, it was time for breakfast. According to Bozo’s time calculations, Dan needed to drag his lazy butt out of bed and get moving.

“All right, all right,” Dan grumbled, giving the dog a fond whack on his empty-sounding head. “I’m up. Are you happy?”

In truth the dog was happy, slobbery grin and all.

Tucson, Arizona

Saturday, June 6, 2009, 1:15 P.M.

93º Fahrenheit

Abby turned the key in the ignition and listened as the powerful V-8 engine roared to life. There was maybe the tiniest squeal, as though a fan belt might be slipping a bit, but the motor settled into a steady hum and the air-conditioning came on full blast—blazingly hot at first, but then cooling. While Abby waited a few moments for the steering wheel to be cool enough to touch, she picked up her cell.

Still careful with her newly applied polish, she hit the green send button twice and called Tohono Chul for the first time that afternoon but for the seventh time that day. She wasn’t surprised when she was put on hold. Abby, of all people, understood what Shirley Folgum was up against. Trying to ride herd on that evening’s party was a complicated proposition.

In Tohono Chul’s annual calendar, the celebration of the night-blooming cereus was an enormous undertaking. On that night alone, as many as two thousand people would show up at the park for the festivities, arriving well after dark and not leaving until early the next morning. All of that would have been complicated enough, if it could have been handled in the established way.

Most big recurring nonprofit-style events come with certain unvarying logistics. Worker bees needed to be organized. Invitations have to be issued. Potential attendees need to be given “Save the date” information. Contracts for entertainment and catering need to be arranged. All of those things held true for the night-blooming cereus party. The big difference—and the big complication—came with the reality that no one ever knew exactly when the party would take place. Not until the very last minute.

Despite years of patient analysis and study by any number of very talented botanists, despite countless computer models examining weather data—daytime temperatures, nighttime temperatures, dew points, barometric pressures, and all points in between—no one had yet been able to crack the code as to when exactly the Queen of the Night would deign to make her annual appearance. Scientific study suggested it would happen sometime between the end of May and the middle of July. As a result of this uncertainty, all preparations had to be ironed out well in advance and then put in abeyance but ready for immediate last-minute execution.

It turned out that was how Abby Tennant herself had stumbled into the event for the first time—at the last minute.

Toward the end of her first June in Tucson, Abby had been dreadfully homesick for her friends and relations back home in Ohio. For one thing, the appalling June heat was nothing short of debilitating. She had almost decided to give up and go back home when a new neighbor, Mildred Harrison, had called.

“There’s going to be a special party at Tohono Chul tomorrow night,” Mildred had said. “Would you like to come along as my guest?”

Abby’s new town house in what was billed as an “active adult community” on Tucson’s far northwest side was just down the street from the botanical garden. She had driven past the rock wall entrance numerous times, but she hadn’t ever considered stopping in. Somehow she had never guessed that one of the world’s ten best botanical gardens would be right there, hiding out in the middle of Tucson.

What interesting plants could possibly grow in the desert? Abby had wondered in all her midwestern arrogance. From what she personally had observed, there seemed to be precious few plants of any kind in this desolate outpost of civilization where, even in May, the heat had been more than Abby could tolerate.

“I suppose they’re holding it at night because it’s too hot to have a garden party during the day,” Abby had groused sarcastically.

Mildred had laughed aloud at that. “It’s a party in honor of the night-blooming cereus,” she explained. “It’s the flower on the deer-horn cactus. We call it the Queen of the Night. Tohono Chul has more than eighty plants that are set to bloom this year, and they all blossom at the same time. They open up around sunset and are gone by sunrise the next morning. Someone called just now to let me know that the bloom will be tomorrow night. Are you coming or not?”

Mildred sometimes reminded Abby of her older sister, Stephanie, who was at times a bit overbearing and more than a little outspoken. On this occasion, Abby had dutifully slipped into full little-sister mode.

“I suppose,” she had agreed reluctantly.

The next day she had tried her best to back out of the engagement, but Mildred wouldn’t hear of it. Around nine o’clock that evening, Abby had ridden over to Tohono Chul’s parking lot in Mildred’s aging Pontiac. Arriving in low spirits and with even lower expectations, Abby was surprised to find the parking lot jammed with cars and parking attendants. Along with hordes of other enthusiastic attendees, Abby and Mildred had walked into the park following footpaths that were lit with candles in small paper bags.

“They’re called luminarias,” Mildred explained. “They’re traditional Mexican.”

Abby was astonished when she saw the throngs of people who were there that night. She kept wondering what all the fuss was about—but only until she saw a night-blooming cereus in the flesh. Once she caught sight of that first lush white blossom, Abby Tennant fell in love.

She couldn’t fathom how such a magnificent white flower could burst forth from what appeared to be a skimpy stick of thorny cactus. She was astonished to find that many of the gorgeous blossoms were as big across as one of Abby’s eight-inch pie plates. They reminded her of her next-door neighbor’s prizewinning dahlias back home in Ohio, but these weren’t dahlias, and the heady perfume that drifted away from each flower on the hot summer air was subtle but elegantly sweet, reminiscent of orange blossoms, but not quite the same.

Abby was dumbstruck. “They’re so beautiful!” she had exclaimed.

“Aren’t they,” Mildred said, nodding in agreement. “And now you know why it’s called the Queen of the Night. By the time the sun comes up tomorrow, the blossoms will be gone.”

Abby Tennant’s first encounter with the night-blooming cereus marked the real beginning of her new life, although her name was still Abby Southard back then. She had been so enchanted by seeing the flowers that she had insisted on taking Mildred to lunch at the Tohono Chul Tea Room the very next week. In the confines of the small cool rooms of what had once been a ranch house, Abby began to see the things about Tucson that she had been missing before—the friendliness of the people, Mildred included, for one thing, and the many subtle beauties of the desert for another.

Abby had taken out her own membership at Tohono Chul only a week or so later. Walking the park’s many manicured paths, she gradually acclimated herself to the heat of her new home. She learned to mark the changing seasons by something other than changing leaves. In spring she saw the profusion of yellow flowers on the prickly pear and the fuchsia-colored blossoms of the barrel cactus. In early summer she came to love the bright yellow blooms standing out against the green branches of the springtime paloverde and the dusky pinks and lavenders on the brooding ironwood. She loved watching the birds, especially the brightly colored hummingbirds that hovered around the equally brightly colored flowers.

Somehow, in the process of exploring this desert oasis, Abby Tennant found peace and came to terms with her new home and her new life. By the time of the first snow-fall in Columbus that first year, she was no longer home-sick. When Christmas rolled around and her friends were complaining about the weather, Abby took herself back to the park and volunteered her services.

At first she knew so little that all she could do was work as a stocker and a cashier in the museum shop. Later, once she was better adjusted to the climate, she went through docent training so she could lead tours and speak knowledgeably about the native plants of her newly adopted home. Because of her enduring fascination with the night-blooming cereus, it was a natural progression of her volunteerism that she went from leading daytime tours to working on the annual Queen of the Night party.

Initially she served on the Queen of the Night Committee, but when the complexity of the event outstripped the committee’s groupthink capability, Abby had finally given up and taken charge. When she came on board, there had been a complicated phone-tree system for notifying workers and guests of the impending bloom. Under her direction, phone trees had given way to a more streamlined form of e-mail notices. But after five years of running the show, it was time to pass the reins to someone else, and Shirley Folgum was her handpicked successor.

“So how are things?” Abby asked when Shirley finally came on the line. “Did you hear back from the band?”

“I was talking to the manager when you called. They’ll be here for a sound check no later than five. I told them to come in by way of the loading dock.”

“And the caterer?”

“She’s having trouble locating servers.”

“Don’t worry. She’ll find them. This party is a big deal for her, and we pay her a bundle of money during the summer when there’s not much else going on. She’ll come through. She always does.

“What about the storyteller?” Abby asked.

Abby had come to love the enduring Tohono O’odham legend about the wise old grandmother whose bravery had given rise to the Queen of the Night. Including that story in the annual festivities was one of the ways Abby had put her own distinctive stamp on the party. She insisted that each year some guest of honor would come to the event and recount the story that had struck a chord in her heart. It seemed to Abby that in saving her grand-son, Wise Old Grandmother had saved Abby Tennant as well.

“That’s handled,” Shirley reported. “Dr. Walker and her mother are planning to have lunch in the Tea Room this afternoon before the party starts. Unfortunately, she’s due back at work in the ER at the hospital in Sells by midnight. That means the last scheduled storytelling event can’t be any later than nine.”

“Good,” Abby said. “Earlier is better than later.”

“Are you going to stop by for a last-minute checklist?” Shirley asked.

“No,” Abby said with a laugh. “I don’t think that’s necessary. It sounds as though you have everything under control.”

Tucson, Arizona

Saturday, June 6, 2009, 1:30 P.M.

93º Fahrenheit

Lani Dahd used her key to unlock the front door of her parents’ house. She stepped inside, with Gabe following close on her heel. He had been here before and was always astonished by the place.

For one thing, the house, built of river rock, was bigger than any of the houses he knew on the reservation. Although the people who lived here were Milgahn, Anglos, the place was full of a rich profusion of baskets—Tohono O’odham baskets. There were yucca and bear-grass baskets on every available surface—on walls and tables and the mantelpiece. Gabe had been told that many of them had been made by his great-aunt Rita.

“How did your parents get so many baskets?” Gabe had asked. “Are they rich?”

Lani Dahd thought about that for a moment before she answered. By reservation standards, the Anglo couple who had adopted her when she was little more than a toddler were rich beyond measure.

“Yes,” she said finally. “I suppose they are.”

“But why?” Gabe asked.

“Because my mother writes books,” Lani answered.

“What about your father?”

“He was a police officer.”

“Why are they so old?” Gabe asked.

Lani’s father was almost seventy. Her mother was in her mid-sixties. In the Anglo world that wasn’t so very old, but on the reservation, where people were often cut down by alcoholism and diabetes in their forties and fifties, that seemed like a very advanced age.

“They just are,” she said.

“Why do they have different names?” Gabe asked. “Mr. Walker and Mrs. Ladd. Aren’t they married?”

“Yes, they’re married,” Lani explained, “but my mother was already writing books by then. It made sense for her to keep her own name instead of changing it to someone else’s.”

This time Gabe was without questions as he followed Lani through the house. While she stopped off in a bathroom, Gabe walked on alone to the sliding door that he knew led to the patio.

Damsel, the household dog, stood outside the sliding door. Gabe opened the door and leaned down to pet the dog. Looking away from Damsel, he saw Mrs. Ladd—an older Milgahn woman with pale skin and silvery hair— sitting in the shade of a little shelter on the far side of the pool. A very ugly blind man was sitting there with her.

Once again the dog demanded Gabe’s attention. When he turned away from Damsel, Lani was stepping through the slider and coming outside. By then the man had disappeared. Gabe hadn’t heard him leave. He glanced around the backyard, looking for him. It seemed curious that he could have left so silently, but the man was nowhere to be seen. He was simply gone.

“Mom,” Lani said, frowning when she noticed her mother’s bathrobe and bare feet. “Why aren’t you dressed?”

“I am dressed,” Diana said. “What’s wrong with a robe?”

“But I thought you were going into town with us—to Tohono Chul. The three of us have a reservation for lunch at the Tea Room, and then tonight there’s the night-blooming cereus party.”

“I can’t,” Diana said. “I’m busy.”

Lani had lived with her adoptive mother’s career as a reality all her life. From an early age she had understood how deadlines worked. When there was something to do with writing that had to be completed by a certain time, her mother was simply unavailable.

“What?” Lani asked. “An emergency copyediting job? How come the deadlines always come from the publisher and never the other way around?”

“Not copyediting,” Diana said. “Something else.”

“Look,” Lani said. “It’s Saturday afternoon. You’ve already worked all morning. Let it go. I talked to Dad. He’s on his way to Casa Grande to see a friend of his. Take a break. Come with us right now. It’ll be fun. The blossoms start opening around eight. I’ll have you back home no later than ten-thirty. You can work all day tomorrow if you need to.”

Diana thought about that for a moment. Finally, making up her mind, she picked up her computer. “All right,” she said. “I’ll go get dressed.”

She stood up and walked into the house, closing the door behind her.

“Who was that man?” Gabe asked.

“What man?”

“The man who was talking to your mother.”

“I didn’t see any man,” Lani said.

“He was right there,” Gabe said, “and then he was gone.”

Lani glanced around the yard. Like Gabe, she saw no one. “Maybe he went out through the gate.”

Gabe shook his head.

“What did he look like? Was he young or old?”

“Old,” Gabe said. “The skin on his face was all lumpy.”

“Like wrinkled?”

“No. Bumpy. Like a popover when you cook it.”

In other tribes, popovers are called fry bread. Flattened pieces of dough are dropped into hot grease. As the dough cooks, the outside surface fills with air and puffs up.

Despite the hot air around her, Lani Walker felt a chill. She knew of only one man whose face had puffed up like a popover when it was covered with hot grease thrown by her mother, but that had happened long before Lani was born. Lani knew about it not only because her brother, who had been there at the time, had told her the story. Lani also knew because she’d seen the photographs in her mother’s book, which had also mentioned that Andrew Philip Carlisle had been dead for years.

“He’s not here now,” Lani said. “You must have been mistaken. Come on,” she added. “Oi g hihm.”

Directly translated, that expression means “Let us walk.” In the vernacular of the reservation, it means: “Let’s get in the pickup and go.”

Gabe evidently understood that this was one time when he’d be better off not asking any questions. Without a word of objection and with the dog at his side, he came into the house behind Lani, took a seat on the couch in a room filled with beautiful Tohono O’odham baskets, and waited patiently until it was time to leave.

Tucson, Arizona

Saturday, June 6, 2009, 1:00 P.M.

93º Fahrenheit

While the coffeepot burbled and burped, Dan dished up Bozo’s food—dry dog food along with a dollop of canned food for flavor. Dan couldn’t help but notice that the tinned dog food—beef with gravy—smelled more appetizing than some of the MREs he had encountered during his tour of duty in Iraq.

Our tour of duty, Dan corrected himself mentally as he placed the dish of food in front of the salivating dog. He still remembered his first one-sided conversation with the dog no one had wanted.

“Look,” he had said while Bozo listened to his voice with rapt, prick-eared attention. “Let’s get one thing straight. When we work, we work; when we play, we play, but you’ve got to know the difference.”

“Hey,” one of the guys had said, pointing and laughing. “Looks like Chief here is turning into one of those dog whisperers. Is it possible old Bozo actually understands Apache?”

From the time he was four, Dan had been raised by his grandparents on the San Carlos Reservation in Arizona, where Dan had been ridiculed for being half Anglo and half Apache. Back then he had coped with his tormentors by playing class clown, so maybe Bozo had a point. And maybe that’s one of the reasons Dan and Bozo had bonded. Daniel Pardee was in Iraq wearing his country’s uniform and doing his country’s job, but he was sick and tired of the constant jokes about his Apache background. Maybe Bozo was tired of the jokes, too.

“I was just telling him that some of the people around here are jerks,” Dan replied. “I told him he needs to know who his friends are.”

By the time Dan’s deployment neared its end, he had pretty much resigned himself to leaving Bozo behind. By then Bozo’s reputation was such that the other guys were clamoring to take him on. That was when Ruthie’s “Dear John” letter arrived. He and Ruthie Longoria had been childhood sweethearts and had dated exclusively all through high school. The idea that they would marry eventually had been a foregone conclusion, but the ending had been all too typical. Somehow Dan had known what was up before he even opened the envelope. For one thing, she had sent it via snail mail rather than over the Net.

“We’re too young to make this kind of commitment,” she had told him. “We both need to see other people, but we can still be friends.” Yada yada yada.

Sure, like that’s going to happen! It was long after Dan had come back home that he finally learned the truth. Ruthie had already found a new man before she ever cut Dan loose.

Still, at the time he read the letter, he was pissed as hell—more angry than sad—but he was also grateful. He understood that he had dodged a bullet as real as any of the live ammunition on the ground in Iraq. If that was the kind of woman Ruthie Longoria was, he was better off knowing about it before the wedding rather than after—a wedding and honeymoon he’d been dutifully saving money for the whole time he had been in the service.

With that monetary obligation off the table, however, Dan decided to cut his losses. If he couldn’t keep his woman, he would sure as hell keep his dog. So Dan took the money he had set aside to pay for a wedding and paid Bozo’s way home instead. It took all the money he’d had and more besides. His maternal grandfather had helped, and so had Justin Clifford’s family. Finally all the effort paid off. After months of paperwork and red tape and after being locked in quarantine for weeks, Bozo came home—home to Arizona; home to San Carlos; home to being a half-Apache dog.

With the wedding in mind, Dan had lined up a postmilitary job with a rent-a-cop security outfit in Phoenix, but that was because Ruthie loved Phoenix and wanted to live there instead of on the reservation, and that’s exactly where she and her new boyfriend—now husband— had gone to live.

Dan did not love Phoenix—at all. Instead of taking that security job, he went back to the reservation, stayed with Gramps, as he called Micah Duarte, his widowed grandfather, the man who had raised him. Sitting in the quiet of Gramps’s small but tidy house, Dan had tried to figure out what he wanted to do with the rest of his life. At age twenty-nine it had seemed that he was too old to go back to college, even though his veteran status would have made that affordable. After the excitement of Iraq, Dan was bored, and so was Bozo. And even though Gramps never said a word, Dan worried that he and his dog were wearing out their welcome.

Then one day two years earlier, when they were eating breakfast at the kitchen table, Gramps put a newspaper in front of him.

“Here,” he said, pointing. “Read this. It sounds like something you’d be good at.”

That article, in the Arizona Sun, told about a special group of Indian trackers, the Shadow Wolves, who worked homeland security on the Tohono O’odham Nation west of Tucson by patrolling the seventy miles of rugged reservation land that lay next to the Mexican border. Members of the elite force came from any number of tribes and were required to be at least one quarter Indian. Dan qualified on that score, with a quarter to the good since he was half Indian and half Anglo. Shadow Wolves needed to be expert trackers, and Dan qualified there, too.

His taciturn grandfather, who had spent all his adult life working on a dairy farm outside of Safford, may not have been long on language skills, but he had taught his grandson how to ride, hunt, and shoot, occasionally doing all three at once.

Micah Duarte counted among his ancestors one of the Apache scouts who had trailed Geronimo into Mexico and had helped negotiate the agreement that had brought him back to the States. In other words, being a tracker was in Daniel’s blood, but Micah Duarte had translated bloodlines into firsthand experience by teaching his grandson everything he knew.