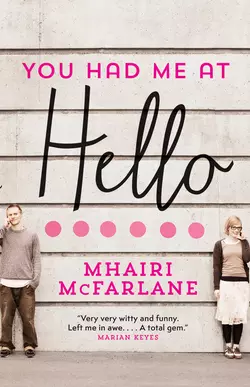

You Had Me At Hello

Mhairi McFarlane

What happens when the one that got away comes back? Find out in this sparkling comedy from bestseller, Mhairi McFarlane.‘Think of the great duos of history. We're just like them.’‘You mean like Kylie and Jason? Torvill and Dean? Sonny and Cher?’‘I think you’ve missed the point, Rachel.’Rachel and Ben. Ben and Rachel. It was them against the world. Until it all fell apart. It’s been a decade since they last spoke, but when Rachel bumps into Ben one rainy day, the years melt away.They’d been partners in crime and the best of friends. But life has moved on: Ben is married. Rachel is not. Yet in that split second, Rachel feels the old friendship return. And along with it, the broken heart she’s never been able to mend.Hilarious, heartbreaking and everything in between, you’ll be hooked from their first ‘hello’.

For Jenny

Who I Found At University

Table of Contents

Title Page (#u20a0d249-527c-5e4b-b45e-e07ce3262767)

Dedication (#ua2dcec9d-2261-5bb7-8ef9-1ffe9c000409)

Prologue (#u7d3eb11f-f9a7-5d71-89ad-8f85202b5c52)

Chapter 1 (#u9f507e58-5a49-5c0d-8361-5a4fb0bcc36c)

Chapter 2 (#ua5fa56d3-1a09-5371-9bf3-7af723cbf4e9)

Chapter 3 (#u9b8565cc-dee3-5230-974e-5e9adbe6fdf6)

Chapter 4 (#u6d867b41-c8f5-5412-b251-49fddcea86de)

Chapter 5 (#ufb4925c8-45aa-51d2-9f86-cb37f8754809)

Chapter 6 (#u42765a93-140f-50d6-96cf-0fe84f8b5a4f)

Chapter 7 (#u8df39117-816d-503a-a36d-f8d7511ed68d)

Chapter 8 (#uffdf1e22-7ba0-5160-a969-7fa5e7708df8)

Chapter 9 (#ufe17892b-0b9c-532b-aa55-c98daa1f5105)

Chapter 10 (#ufac16dae-d171-5914-bc6c-a01cb3d91948)

Chapter 11 (#u3de28969-f1bd-5326-ab2d-fe3b8efc4429)

Chapter 12 (#u269b6dca-6f47-5778-84bb-014fa5fc2812)

Chapter 13 (#u85bf2f71-99c8-524e-b84d-df6f3fd3e0e6)

Chapter 14 (#u569a5510-087f-5895-b3e1-f8a1638facb2)

Chapter 15 (#u4186073d-b485-5bea-851b-469af35a2335)

Chapter 16 (#u33f3e1d5-e7f1-564f-af7b-c61f9631c388)

Chapter 17 (#u9a956839-803d-510c-ada0-0465f7a2d154)

Chapter 18 (#u6790db96-74f1-54a5-9d83-b8f8ab38b993)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 44 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 45 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 46 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 47 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 48 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 49 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 50 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 51 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 52 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 53 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 54 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 55 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 56 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 57 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 58 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 59 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 60 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 61 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 62 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 63 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 64 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 65 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 66 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 67 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 68 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 69 (#litres_trial_promo)

So that’s it. Rachel and Ben’s story has been told. (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE

‘Oh bloody hell, of all the luck …’

‘What?’ I asked.

I batted a particularly plucky and irrepressible wasp away from my Coke can. Ben was shielding his face with his hand in that way which only renders you more conspicuous.

‘Professor McDonald. You know, Egg McMuffin Head. I owed him an essay on Keats a week ago. Has he seen me?’

I looked over. Across the afternoon-sun-dappled lawn, the professor had stopped in his tracks and was doing the full pointing-finger Lord Kitchener impression, even down to mouthing the word ‘YOU’.

‘Er. Yes.’

Ben peered through a gap in his fingers at me.

‘Maybe yes or hell yes?’

‘Like a tweedy, portly, bald Scottish Scud missile has your exact coordinates and is ripping across the grass to take you out, yes.’

‘Right, OK, think, think …’ Ben muttered, looking up into the leaves of the tree we were sitting beneath.

‘Are you going to try to climb it? Because Professor McDonald looks the type to wait for the fire crews at dusk.’

Ben’s eyes cast around at the detritus of lunch, and our bags on the ground, as if they contained an answer. I didn’t think an esteemed academic getting a face full of Karrimor rucksack was likely to help. His gaze came to rest on my right hand.

‘Can I borrow your ring?’

‘Sure. It’s not magical though.’ I twisted it off and handed it over.

‘Stand up?’

‘Eh?’

‘Stand. Up.’

I got to my feet, brushing the grass off my jeans. Ben balanced himself on one knee and held aloft a piece of gothicky silver jewellery I’d got for four quid at the student market. I started laughing.

‘Oh … you idiot …’

Professor McDonald reached us.

‘Ben Morgan …!’

‘Sorry, sir, I’m just in the middle of something rather important here.’

He turned back to me.

‘I know we’re twenty years old and the timing of this proposal might have been forced due to … external pressures. But, irrespective of this, you are amazing. I know I will never meet another woman I care about as much as you. This feeling just builds and builds …’

Professor McDonald folded his arms, but incredibly, he was smiling. Unbelievable. The Ben chutzpah triumphed again.

‘Are you sure that feeling isn’t the revenge of the sweetcorn and tinned hotdog tortilla you and Kev made last night?’ I asked.

‘No! My God – you’ve taken me over. It’s my head, my heart, my gut …’

‘Careful now, lad, I wouldn’t go much further in the inventory,’ Professor McDonald said. ‘The weight of history is upon you. Think of the legacy. It’s got to inspire.’

‘Thanks, sir.’

‘You don’t need a wife, you need Imodium,’ I said.

‘I need you. What do you say? Marry me. A simple ceremony. Then you can move into my room. I’ve got an inflatable mattress and a stained towel you can fold up and use as a pillow. And Kev’s perfecting a patatas bravas recipe where you boil the potatoes in Heinz tomato soup.’

‘Lovely offer as it is, Ben. Sorry. No.’

Ben turned towards Professor McDonald.

‘I’m going to need some compassionate leave.’

1

I get home slightly late, blown in the door by that special Manchester rain that manages to be both vertical and horizontal at the same time. I bring so much water into the house it feels as if the tide goes out and leaves me draped across the bottom of the stairs like a piece of seaweed.

It’s a friendly, unassuming-looking place, I think. You could peg us as early thirty-something childless ‘professionals’ in a two-minute tour. Framed prints of Rhys’s musical heroes. Shabby chic with a bit more of the former than the latter. And dark blue gloss paint on the skirting boards that makes my mum sniff: ‘Looks a bit community centre project.’

The house smells of dinner, spicy and warm, and yet there’s a definite chill in the air. I can sense Rhys is in a mood even before I set eyes on him. As I walk into the kitchen, something about the tension in his shoulders as he hovers over the stove makes it a certainty.

‘Evening, love,’ I say, pulling sodden hair out of my collar and unwinding my scarf. I’m shivering, but I have that weekend spring in my step. Everything’s a little easier to bear on a Friday. He grunts indistinctly, which could be a hello, but I don’t query it lest I be blamed for opening hostilities.

‘Did you get the tax disc?’ he asks.

‘Oh shit, I forgot.’

Rhys whips round, knife dangling in his hand. It was a crime of passion, your honour. He hated tardiness when it came to DVLA paperwork.

‘I reminded you yesterday! It’s a day out now.’

‘Sorry, I’ll do it tomorrow.’

‘You’re not the one who has to drive the car illegally.’

I’m also not the one who forgot to go last weekend, according to the reminder in his handwriting on the calendar. I don’t mention this. Objection: argumentative.

‘They tow them to the scrap yard, you know, even if they’re parked on the pavement. Zero tolerance. Don’t blame me when they crush it down to Noddy size and you’ve got to get buses.’ I have an image of myself in a blue nightcap with a bell on the end of it.

‘Tomorrow morning. Don’t worry.’

He turns back and continues hacking at a pepper that may or may not have my face on it. I remember that I have a sweetener and duck out to retrieve the bottle of red from the dripping Threshers bag.

I pour two thumping glasses and say: ‘Cheers, Big Ears.’

‘Big Ears?’

‘Noddy. Never mind. How was your day?’

‘Same old.’

Rhys works in graphic design for a marketing company. He hates it. He hates talking about it even more. He quite likes lurid tales from the front line of reporting on Manchester Crown Court trials, however.

‘Well today a man responded to the verdict of life sentence without parole with the immortal words: “This wrong-ass shit be whack.”’

‘Haha. And was it?’

‘Wrong-ass? No. He did kill a bunch of people.’

‘Can you put “wrong-ass shit” in the Manchester Evening News?’

‘Only with asterisks. I definitely had to euphemise the things his family were saying as “emotional shouts and cries from the public gallery”. The only word about the judge that wasn’t swearing was “old”.’

Chuckling, Rhys carries his glass to the front room. I follow him.

‘I did some reception research about the music today,’ I say, sitting down. ‘Mum’s been on to me fretting that Margaret Drummond at cake club’s nephew had a DJ in a baseball cap who played “lewd and cacophonous things about humps and cracks” before the flower girls’ and page boys’ bedtimes.’

‘Sounds great. Can she get his number? Maybe lose the cap though.’

‘I thought we could have a live singer. There’s someone at work who hired this Elvis impersonator, Macclesfield Elvis. He sounds brilliant.’

Rhys’s face darkens. ‘I don’t want some cheesy old fat fucker in Brylcreem singing “Love Me Tender”. We’re getting married at Manchester Town Hall, not the Little McWedding Chapel in Vegas.’

I swallow this, even though it doesn’t go down easy. Forgive me for trying to make it fun.

‘Oh. OK. I thought it might be a laugh, you know, get everyone going. What were you thinking?’

He shrugs.

‘Dunno.’

His truculence, and a pointed look, tells me I might be missing something.

‘Unless … you want to play?’

He pretends to consider this.

‘Yeah, ’spose we could. I’ll ask the lads.’

Rhys’s band. Call them sub-Oasis and he’ll kill you. There are a lot of parkas and squabbles though. The thing we both know and never say is that he hoped his previous group, back in Sheffield, would take off, while this is a thirty-something hobby. I’ve always accepted sharing Rhys with his music. I just didn’t expect to have to on my wedding day.

‘You could do the first half an hour, maybe, and then the DJ can start after that.’

Rhys makes a face.

‘I’m not getting everyone to rehearse and set up and then play for that long.’

‘All right, longer then, but it’s our wedding, not a gig.’

I feel the storm clouds brewing and rolling, a thunderclap surely on its way. I know his temper, this type of argument, like the back of my hand.

‘I don’t want a DJ either,’ he adds.

‘Why not?’

‘They’re always naff.’

‘You want to do all the music?’

‘We’ll do iPod compilations, Spotify, whatever. Put them on shuffle.’

‘OK.’

I should let this go, try when he’s in a better mood, but I don’t.

‘We’ll have The Beatles and Abba and stuff for the older generation on there, though? They’re not going to get it if it’s all fuck-you-I-won’t-do-what-you-tell-me and blaring amps.’

‘“Dancing Queen”? No bloody way. Even if your cousin Alan wants to mince around to it.’ He purses his lips and makes a ‘flapping hands at nipple level’ Orville the Duck gesture that could be considered gratuitously provocative.

‘Why do you have to behave as if this is such a hassle?’

‘I thought you wanted to get married on our terms, in our way. We agreed.’

‘Yes, our terms. Not your terms,’ I say. ‘I want you to have a chance to talk to our friends and family. It’s a party, for everyone.’

My eyes drifted to my engagement ring. Why were we getting married, again? A few months ago, we were tipsy on ouzo digestifs in a Greek restaurant, celebrating Rhys getting a decent bonus at work. It came up as one of the big things we could spend it on. We liked the idea of a bash, agreed it was probably ‘time’. There was no proposal, just Rhys topping up my glass and saying ‘Fuck it, why not, eh?’ and winking at me.

It felt so secure, and right, and obvious a decision in that steamy, noisy dining room, that night. Watching the belly dancer dragging pensioners up to gyrate alongside her, laughing till our bellies hurt. I loved Rhys, and I suppose in my agreement was an acceptance of: well, who else am I going to marry? Yes, we lived with a grumbling undercurrent of dissatisfaction. But like the toad-speckles of mouldy damp in the far corner of the bathroom, it was going to be a lot of upheaval to fix, and we never quite got round to it.

Though we’d waited long enough, I’d never really doubted we would formalise things. While Rhys still had the untamed hair and wore the eternal student uniform of grubby band t-shirts, distressed denim and All Stars, underneath it all, I knew he wanted the piece of paper before the kids. We called both sets of parents when we got home, ostensibly to share our joy, maybe also so we couldn’t go back on it when we’d sobered up. Not moonlight and sonatas but, as Rhys would say, life isn’t.

Now I picture this day, supposedly the happiest day of our lives, full of compromises and swallowed irritation and Rhys being clubby and standoffish with his band mates, the way he was when I first met him, when being in his gang had been all my undeveloped heart muscle desired.

‘For how long is the band going to be the third person in this relationship? Are you going to be out at rehearsals when I’m home with a screaming baby?’

Rhys pulls the wine glass from his lips.

‘Where’s that come from? What, I’ve got to be a different person, give up something I love, to be good enough for you?’

‘I didn’t say that. I just don’t think you playing should be getting in the way of us spending time together on our wedding day.’

‘Ha. We’ll have a lifetime together afterwards.’

He says this as if it’s a sentence in Strangeways, with shower bumming, six a.m. exercise drills in the yard and smuggling coded messages to people on the outside. Won’t. Let. Me. Come. To. Pub …

I take a deep breath, and feel a hard, heavy weight beneath my ribcage, a pain that I could try to dissolve with wine. It has worked in the past.

‘I’m not sure this wedding is a good idea.’

It’s out. The nagging thought has bubbled up right through from subconscious to conscious and has continued onwards, leaving my mouth. I’m surprised I don’t want to take it back.

Rhys shrugs.

‘I said to do a flit abroad. You wanted to do it here.’

‘No, I mean I don’t think getting married at the moment is a good idea.’

‘Well, it’s going to look pretty fucking weird if we call it off.’

‘That’s not a good enough reason to go through with it.’

Give me a reason. Maybe I’m the one sending desperate messages in code. I realise that I’ve come to an understanding, woken up, and Rhys isn’t hearing the urgency. I’ve said the sort of thing we don’t say. Refusal to listen isn’t enough of a response.

He gives an extravagant sigh, one full of unarticulated exhaustion at the terrible trials of living with me.

‘Whatever. You’ve been spoiling for a fight ever since you got home.’

‘No I haven’t!’

‘And now you’re going to sulk to try to force me into agreeing to some DJ who’ll play rubbish for you and your divvy friends when you’re pissed. Fine. Book it, do it all your way, I can’t be bothered to argue.’

‘Divvy?’

Rhys takes a slug of wine, stands up.

‘I’m going to get on with dinner, then.’

‘Don’t you think the fact we can’t agree on this might be telling us something?’

He sits again, heavily.

‘Oh, Jesus, Rachel, don’t try to turn this into a drama, it’s been a long week. I haven’t got the energy for a tantrum.’

I’m tired, too, but not from five days of work. I’m tired of the effort of pretending. We’re about to spend thousands of pounds on the pretence, in front of all of the people who know us best, and the prospect’s making me horribly queasy.

The thing is, Rhys’s incomprehension is reasonable. His behaviour is business as usual. This is business as usual. It’s something in me that’s snapped. A piece of my machinery has finally worn out, the way a reliable appliance can keep running and running and then, one day, it doesn’t.

‘It’s not a good idea for us to get married, full stop,’ I say. ‘Because I’m not sure it’s even a good idea for us to be together. We’re not happy.’

Rhys looks slightly stunned. Then his face closes, a mask of defiance again.

‘You’re not happy?’

‘No, I’m not happy. Are you?’

Rhys squeezes his eyes shut, sighs and pinches the bridge of his nose.

‘Not at this exact moment, funnily enough.’

‘In general?’ I persist.

‘What is happy, for the purposes of this argument? Prancing through meadows in a stoned haze and see-through blouse, picking daisies? Then no, I’m not. I love you and I thought you loved me enough to make an effort. But obviously not.’

‘There is a middle ground between stoner daisies and constant bickering.’

‘Grow up, Rachel.’

Rhys’s stock reaction to any of my doubts has always been this: a gruff ‘grow up’, ‘get over it’. Everyone else knows this is simply what relationships are and you have unrealistic expectations. I used to like his certainty. Now I’m not so sure.

‘It’s not enough,’ I say.

‘What are you saying? You want to move out?’

‘Yes.’

‘I don’t believe you.’

Neither do I, after all this time. It’s been quite an acceleration, from nought to splitting up in a few minutes. I’ve practically got hamster cheeks from the g-force. This could be why it’s taken us so long to get round to tying the knot. We knew it’d bring certain fuzzy things into sharper focus.

‘I’ll start looking for places to rent tomorrow.’

‘Is this all it’s worth, after thirteen years?’ he asks. ‘You won’t do what I want for the wedding – see ya, bye?’

‘It’s not really the wedding.’

‘Funny how these problems hit you now, when you’re not getting your own way. Don’t recall this … introspection when I was buying the ring.’

He has a point. Have I manufactured this row to give me a reason? Are my reasons good enough? I weaken. Perhaps I’m going to wake up tomorrow and think this was all a mistake. Perhaps this dark, apocalyptic mood of terrible clarity will clear up like the rain that’s still pelting down outside. Maybe we could go out for lunch tomorrow, scribble down the shared song choices on a napkin, start getting enthused again …

‘OK … if this is going to work, we have to change things. Stop getting at each other all the time. See a counsellor, or something.’

He can offer me next to nothing here, and I will stay. That’s how pathetic my resolve is.

Rhys frowns.

‘I’m not sitting there while you tell some speccy wonk at Relate about what a bastard I am to you. I’m not putting the wedding off. Either we do it, or forget it.’

‘I’m talking about our future, whether we have one, and all you care about is what people will think if we cancel the wedding?’

‘You’re not the only one who can give ultimatums.’

‘Is this a game?’

‘If you’re not sure after this long, you never will be. There’s nothing to talk about.’

‘Your choice,’ I say, shakily.

‘No, your choice,’ he spits. ‘As always. After all I’ve sacrificed for you …’

This sends me up into the air, the kind of anger where you levitate two feet off the ground as if you have rocket launchers on your heels.

‘You have not given anything up for me! You chose to move to Manchester! You act like I have this debt to you I can never repay and it’s bullshit! That band was going to split up anyway! Don’t blame me because you DIDN’T MAKE IT.’

‘You are such a selfish, spoilt brat,’ he bellows back, getting to his feet as well, because shouting from a seated position is never as effective. ‘You want what you want, and you never think about what other people have to give up to make it happen. You’re doing the same with this wedding. You’re the worst kind of selfish because you think you’re not. And as for the band, how fucking dare you say you know how things would’ve turned out. If I could go back and do things differently—’

‘Tell me about it!’ I scream.

We both stand there, breathing heavily, a two-person Mexican standoff with words as weapons.

‘Fine. Right,’ Rhys says, eventually. ‘I’m going back home for the weekend – I don’t want to stay here and take this shit. Start looking for somewhere else to live.’

I drop back down on the sofa and sit with my hands in my lap. I listen to the sounds of him stomping around upstairs, filling an overnight bag. Tears run down my cheeks and into the neckline of my shirt, which had only just started to dry out. I hear Rhys in the kitchen and I realise he’s turning the light off underneath the pan of chilli. Somehow, this tiny moment of consideration is worse than anything he could say. I put my face in my hands.

After a few more minutes, I’m startled by his voice, right next to me.

‘Is there anyone else?’

I look up, bleary. ‘What?’

‘You heard. Is there anyone else?’

‘Of course not.’

Rhys hesitates, then adds: ‘I don’t know why you’re crying. This is what you want.’

He slams the front door so hard behind him, it sounds like a gunshot.

2

In the shock of my sudden singlehood, my best friend Caroline and our mutual friends Mindy and Ivor rally round and ask the question of the truly sympathetic: ‘Do you want us all to go out and get really really drunk?’

Rhys wasn’t missing in action as far as they were concerned: he’d always seen my friends as my friends. And he used to observe that Mindy and Ivor ‘sound like a pair of Play School presenters’. Mindy is Indian, it’s an abbreviation of Parminder. She calls ‘Mindy’ her white world alias. ‘I can move among you entirely undetected. Apart from the being brown thing.’

As for Ivor, his dad’s got a thing about Norse legends. It’s been a bit of an albatross, thanks to a certain piece of classic children’s animation. Ivor endured the rugby players in our halls of residence at university calling him ‘the engine’ and claiming he made a pessshhhty-coom, pessshhhty-coom noise at intimate moments. Those same rugby players drank each other’s urine and phlegm for dares and drove Ivor upstairs to meet the girls’ floor, which is how we became a mixed-sex unit of four. Our platonic company, combined with his close-shaved head, black-rimmed glasses and love of trendy Japanese trainers led to a frequent assumption that Ivor was gay. He’s since gone into computer game programming and, given there are practically no women in the profession whatsoever, he feels this misconception could see him missing out on valuable opportunities.

‘It’s counter-intuitive,’ he always complains. ‘Why should a man surrounded by women be homosexual? Hugh Hefner doesn’t get this treatment. Obviously I should wear a dressing gown and slippers all day.’

Anyway, I’m not quite ready to face cocktail bar society, so I opt for a night in drinking the domestic variety, invariably more lethal.

Caroline’s house in Chorlton is always the obvious choice to meet, as unlike the rest of us she’s married, and has an amazing one. (I mean house, not spouse – no disrespect to Graeme. He’s away on one of his frequent boys’ golfing weekends.) Caroline is a very well paid accountant for a large chain of supermarkets, and a proper adult: but then, she always was. At university, she wore quilted gilets and was a member of the rowing club. When I used to express my amazement to the others that she could get up early and exercise after a hard night on the sauce, Ivor used to say, groggily: ‘It’s a posh thing. Norman genes. She has to go off and conquer stuff.’

He could be on to something about her ancestry. She’s tall, blonde and has what I believe is called an aquiline profile. She says she looks like an ant eater; if so, it’s kind of ant-eater-by-way-of-Grace-Kelly.

I have the job of slicing limes and salting the rims of the glasses on Caroline’s spotlessly sleek black Corian worktop while she blasts ice, tequila and Cointreau into a slurry in a candy-apple red KitchenAid. In between these deafening bursts, from her regal perch on the sofa, Mindy is gifting us, as usual, with the Tao of Mindy.

‘The difference between thirty and thirty-one is the difference between a funeral and the grieving process.’

Caroline starts spooning out margarita mixture.

‘Turning thirty is like a funeral?’

‘The funeral for your youth. Lots of drink and sympathy and attention and flowers, and you see everyone you know.’

‘And for a moment there we were worried the comparison was going to be tasteless,’ Ivor says, pushing his glasses up the bridge of his nose. He’s sitting on the floor, legs outstretched, one arm similarly outstretched, pointing a remote at something lozenge-shaped that’s apparently a stereo. ‘Have you really got The Eagles on here, Caroline, or is it a sick joke?’

‘Thirty-one is like grieving,’ Mindy continues. ‘Because getting on with it is much worse, but no one expects you to complain any more.’

‘Oh, we expect you to complain, Mind,’ I say, carefully passing her a shallow glass that looks like a saucer on a stem.

‘The fashion magazines make me feel so old and irrelevant, it’s like the only thing I should bother buying is TENA Lady. Can I eat this?’ Mindy removes the lime slice from the side of her glass and examines it.

She is, in general, a baffling mixture of extreme aptitude and total daftness. Mindy did a business degree and insisted throughout she was useless at it and definitely wasn’t going to take on the family firm, which sold fabrics in Rusholme. Then she got a first and picked the business up for one summer, created mail order and online sales, quadrupled the turnover and grudgingly accepted she might have a knack, and a career. Yet on holiday in California recently, when a tour guide announced, ‘On a clear day, with binoculars, you can see whales from here’, Mindy said, ‘Oh my God, all the way to Cardigan Bay?’

‘Lime? Er … not usually,’ I say.

‘Oh. I thought you might’ve infused it with something.’

I collect another glass and deliver it to Ivor, then Caroline and I carry ours to our seats.

‘Cheers,’ I say. ‘To my broken engagement and loveless future.’

‘To your future,’ Caroline chides.

We raise glasses, slurp, wince a bit – the tequila is quite loud in the mix. It makes my lips numb and stomach warm.

Single. It’s been so long since the word applied to me and I don’t feel it yet. I’m something else, in limbo: tip-toeing round my own house, sleeping in the spare room, avoiding my ex-fiancé and his furious, seething disappointment. He’s right: this is what I want, I have less reason than him to be upset.

‘How’s it going, you two living together?’ Caroline asks, carefully, as if she can hear me think.

‘We’re not putting piano wire at neck level across doorways yet. We stay out of each other’s way. I need to step up the house hunt. I’m finding excuses to be out every evening as it is.’

‘How did your mum take it?’ Mindy bites her lip.

Mindy understands that, as one of the two slated bridesmaids, she was the only other person as excited as my mum.

‘Not well,’ I say, with my skill for understatement.

It was awful. The phone call went in phases. The ‘stop playing a practical joke’ section. The ‘you’re having cold feet, it’s natural’ parry. The ‘give it a few weeks, see how you feel’ suggestion. Anger, denial, bargaining, and then – I hope – some sort of acceptance. Dad came on and asked me if it was because I was worrying about the cost, as they’d cover it all if need be. It was then that I cried.

‘I hope you don’t mind me asking, it’s just, you never said …’ Mindy asks. ‘What actually caused the row that made you and Rhys finish?’

‘Oh …’ I say. ‘It was Macclesfield Elvis.’

There’s a pause. Our default setting is pissing about. As the demise of my epically long relationship only happened a week previous, no one knows quite what’s appropriate yet. It’s like after any major tragedy: when’s it OK to start forwarding the email jokes?

‘You shagged Macclesfield Elvis?’ Ivor says. ‘How did it feel to be nailed by The King?’

‘Ivor!’ Mindy wails.

I laugh.

‘Oooh!’ Caroline suddenly exclaims, in a very un-Caroline-like way.

‘Have you sat on something?’ Mindy says.

‘I forgot to say. Guess who I saw this week?’

I’m trying to think which famous person is meant to be my top spot. Unless it’s someone I’ve done a story on, but I spend all day looking at people who are only ever celebrities for the wrong reasons. I doubt a sex attacker on the lam would provoke this delight.

‘Coronation Street or Man U?’ Mindy asks. These are the two main sources of famous people in the city, it’s true.

‘Neither,’ Caroline says. ‘And this is a quiz for Rachel.’

I shrug, crunching on some ice with my back teeth.

‘Uh … Darren Day?’

‘No.’

‘Lembit Opik?’

‘No.’

‘My dad?’

‘Why would I see your dad?’

‘He could be over from Sheffield, having a clandestine affair behind my mum’s back.’

‘In which case I’d announce it in the form of a fun quiz?’

‘OK, I give up.’

Caroline sits back with a triumphant look on her face.

‘English Ben.’

I go hot and cold at the same time, like I’ve suddenly caught the flu. Slight nausea is right behind the temperature fluctuation. Yep, the analogy holds.

Ivor twists round to look at Caroline.

‘English Ben? What kind of nickname is that? As opposed to what?’

‘Is he any relation to Big Ben?’ Mindy asks.

‘English Ben,’ Caroline repeats. ‘Rachel knows who I mean.’

I feel like Alec Guinness in Star Wars when Luke Skywalker turns up at his cave and starts asking for Obi Wan Kenobi. Now there’s a name I’ve not heard in a long, long time …

‘Where was he?’ I say.

‘Going into Central Library.’

‘How about telling old “Two Legs Ivor” who you’re on about?’ Ivor asks.

‘I could be “Hindi Mindy”,’ Mindy offers, and Ivor looks like he’s going to explain something to her, then changes his mind.

‘He was a friend at uni, remember,’ I say, covering my mouth with my glass in case my face is betraying more than I want. ‘Off my course. Hence, English. Ben.’

‘If he was a friend of yours, why is Caroline all … wriggly?’ Mindy asks.

‘Caroline always fancied him,’ I say, glad this is the truth, if nothing like the whole truth, so help me God.

‘Ah.’ Mindy gives me an appraising look. ‘You can’t have fancied him then, because you and Caroline and taste in men – never the twain shall meet.’

I could kiss Mindy for this.

‘True,’ I agree, emphatically.

‘He still looks fine,’ Caroline says, and my stomach starts flopping around like a live crustacean heading for the pot in the Yang Sing kitchen. ‘He was in a gorgeous suit and tie.’

‘A suit, you say? This man is fascinating,’ Ivor says. ‘What a character. I’m compelled to know more. Oh. No, hang on – I’m not.’

‘Did you and he ever …?’ Mindy asks Caroline. ‘I’m trying to place him …’

‘God, no, I wasn’t glamorous enough for him, I don’t think any of us were, were we, Rach? Bit of a womaniser. But somehow nice with it.’

‘Yep,’ I squeak.

‘Wait! I remember Ben! All like, preppy, smart and confident?’ Mindy says. ‘We thought he must be rich and then it was like, no, he just … washes.’ She looks at Ivor, who takes the bait.

‘Oh, rings a vague bell. Poser who was …’ Ivor flips his collar up ‘… Is it handsome in here or is it just me?’

‘He wasn’t like that!’ I laugh, nervously.

‘You lost touch with Ben completely?’ Caroline asks. ‘Not Facebook friends or anything?’

Severed touch with him. Touch was torn in half, like chesting the ribbon at the end of a race.

‘No. I mean, yeah. Not seen Ben since uni.’

And my seven hundred and eighty-one Google searches yielded no results.

‘I’ve seen him at the library a few times, it’s only now it’s clicked and I realised why I recognised him. He must be staying in Manchester. Do you want me to say hello if I see him again, pass on your mobile number?’

‘No!’ I say, with a note of panic not entirely absent from my voice. I feel I have to explain this, so I add: ‘It could sound as if I’m after him.’

‘If you were only friends before, why would he automatically think that?’ Caroline asks, not unreasonably.

‘I’m single after such a long time. I don’t know, it could be misinterpreted. And I’m not looking to … I don’t want it to look like, here’s my single friend who wants me to auction her phone number to men in the street,’ I waffle.

‘Well, I wasn’t going to put it on a card in a phone box!’ Caroline huffs.

‘I know, I know, sorry.’ I pat her arm. ‘I am so, so out of practice at this.’

A pause, with sympathetic smiles from Mindy and Caroline.

‘I’ll hook you up with some hotness, when you’re ready.’ Mindy pats my arm.

‘Woah,’ Ivor says.

‘What?’

‘Judging from the men you do date, I’m trying to imagine the ones you pass over. I’m getting a message from my brain: the server understood your request but is refusing to fulfil it.’

‘Oh, considering your rancid trollops, this is rich.’

‘No, it was that thundering helmet Bruno who was rich, remember?’

‘Aherm, he also had a nice bum.’

‘So there you go,’ Caroline interrupts. ‘Have we cheered you up? Feeling brighter?’

‘Yes. A sort of nuclear glow,’ I say.

‘More serious Slush Puppy?’ Caroline asks.

I hold my glass up.

‘Shitloads, please.’

3

I met Ben at the end of our first week at Manchester University. I initially thought he was a second or third year, because he was with the older team who’d set up trestle tables in my halls of residence bar to issue our accommodation ID cards. In fact, he’d started off as a customer, same as me. In what I’d later discover was a typically garrulous, generous Ben thing to do, he’d offered to help and hopped over the tables when they’d complained they were short-handed.

I wouldn’t have been upright myself, but my hangover had woken me and told me it desperately needed Ribena. The grounds of my halls were as deserted at nine a.m. as if it was dawn. Draining the bottle as I walked back from the shops in the autumn sunshine, I saw a small queue snaking out of the bar’s double doors. Being British, and a nervous fresher, I thought I’d better join it.

When I got to the front and a space appeared in front of Ben, I stepped forward.

His mildly startled but not at all displeased expression seemed to read, quite clearly: ‘Ooh, and you are?’

This startled me back, not least because it somehow wasn’t leery. On a good day (which this wasn’t) I thought I scrubbed up reasonably well but I hadn’t had many looks like this before. It was as if someone had cued music, fluffed my hair, lit me from above and shouted ‘action’.

Ben wasn’t at all my type. Bit skinny, bit obvious, with those brown doe-eyes and that squared-off jaw, bit white bread as Rhys would say. (He had recently come into my life, along with his definitive worldview that, bit by bit, was becoming mine.) And from what I could see of Ben’s upper half, he was clad in sportswear in such a manner that implied he actually played sports. Attractive men, in my eighteen-year-old opinion, played lead guitar, not football. They were scruffy and saturnine, had five o’clock shadows and – recent amendment due to research in the field – chest hair you could lose a gerbil in. Still, I was open-minded enough to allow that Ben would be plenty of other people’s type, and that made the attention pretty damn flattering. The low clouds of my hangover started lifting.

Ben said:

‘Hello.’

‘Hello.’

A beat while we remembered what we were here for. ‘Name?’ Ben said.

‘Rachel Woodford.’

‘Woodford … W …’ He started riffling through boxes of cards. ‘Gotcha.’

He produced a rectangle of cardboard with the name of our halls and a passport photo affixed to it. I’d forgotten I’d sent a handful from a not very flattering session in a shopping centre photo booth. Really bad day, Meadowhall, pre-menstrual. Face like I’d woken up at my own autopsy. Might’ve known they’d come back to haunt me.

‘Don’t laugh at the picture,’ I said, hastily, and potentially counter-productively.

Ben peered at it. ‘I’ve seen worse today.’

He clamped my card in the machine, took the plasticated version out and inspected it again.

‘I know it’s grim,’ I said, holding out my hand. ‘I look like I’m trying to pass a dragon fruit.’

‘I don’t know what a dragon fruit is. I mean, other than a fruit, I’m guessing.’

‘It’s spiky.’

‘Ah OK. Yeah. I ’spose that’d sting a bit.’

Well. That had gone beautifully. Seduction 101: make the attractive boy imagine you straining on the toilet.

This was straight from my greatest hits back catalogue, by the way. Quintessential Rachel, The Cream of Rachel, Simply Rachel. When put on the spot, the linguistic function of my brain offers the same potluck as a one-armed bandit. Crank the handle and ratchet the tension, it rings up any old combination of words.

Ben gave me a smile that turned into laughter. I grinned back.

He kept the card out of my reach.

‘You’re on English?’

‘Yes.’

‘Me too. I haven’t got a clue where I’m meant to be for registration tomorrow. Have you?’

We made an arrangement for him to stop by my room the next morning so we could navigate the arts block together. He found a pen. I scribbled my room number down for him on the nearest thing to hand, a spongy beer mat. I wished I hadn’t spent last night painting every one of my fingernails a different colour, which looked pretty silly in the light of day. I printed ‘Rachel’ in un-joined up letters neatly below, as if I was writing out a label for my coat peg at primary school.

‘About the picture,’ he said, as he took it. ‘You look fine, but you might want to jack the seat up next time. It’s a bit Ronnie Corbett.’

I slid it out again to check. There was an acre of white space above my dishevelled head.

I blushed, started laughing.

‘Spin it,’ Ben mouthed, rotating an imaginary photo booth stool.

I went redder, laughed harder.

‘I’m Ben. See you tomorrow.’

In the style of a policeman in traffic, Ben waved me away with one hand and the next person forward with his other, mock imperiously.

As I dodged round the rest of the queue, I wondered if the well-spoken girl in the room next door to me was too upper middle class to go for a restorative greasy spoon breakfast. On impulse as I left, I glanced back towards Ben, and he was watching me go.

4

In some workplaces, everyone has clusters of framed family portraits on their desk, a tumbler of those novelty gonk pens with tufts of fluff at the end and a mug with their name on. From time to time they cry in the loos and confide in each other and any personal news is round the office in the morning before the kettle’s gone on for a second time. Words like ‘fibroids’ or ‘Tramadol’ or ‘caught him trying on one of my dresses’ are passed about in the spirit of full disclosure.

Mine isn’t one of those workplaces. Manchester Crown Court is full of people moving briskly and efficiently about the place, swishing robes and trading critical information in low voices. The mood is decidedly masculine – it doesn’t encourage confidences that are nothing to do with the business in hand. Therefore I’ve masked physical evidence of my emotional turmoil with an extra layer of make-up, and am squaring my shoulders and heading into battle, congratulating myself on my varnish-thin sheen of competent poise.

I’m getting myself one of the Crown Court vending machine’s famous dung-flavoured instant coffees, served in a plastic cup so thin the liquid burns your fingertips, when I hear: ‘Big weekend was it, Woodford? You look cream crackered!’

Ahhhh, Gretton. Might’ve known he’d burst my bubble.

Pete Gretton is a freelancer, a ‘stringer’ for the agencies as they’re known, with no loyalties. He scours the lists looking for the most unpleasant or ridiculous cases and sells the lowest common denominator to the highest bidder, often following me around and ruining any hope of an exclusive. Misdeed and misery are his bread and butter. To be fair, that’s true of every salaried person in the building, but most of us have the decency not to revel in it. Gretton, however, has never met a grisly multiple homicide he didn’t like.

I turn and give him an appropriately weary look.

‘Good morning to you too, Pete,’ I say, tersely.

He’s very blinky, as if daylight is a shock to him, somehow always reminding me of a ghostly, pink-gilled fish my dad once found lurking in the black sludge at the bottom of the garden pond. Gretton’s evolved to fit the environment of court buildings, subsisting purely on coffee, fags and cellophane-wrapped pasties, with no need for sunshine’s Vitamin D.

‘Only joking, sweetheart. You’re still the most beautiful woman in the building.’

After a conversation with Gretton you invariably want to scrub yourself with a stiff bristled brush under scalding water.

‘What was it?’ he continues. ‘Too much of the old vino collapso? That fella of yours tiring you out?’ He adds a stomach-turning wink.

I take a gulp of coffee with the fresh roasted aroma of farming and agriculture.

‘I split up with my fiancé last month.’

His beady, rheumy little eyes lock on mine, waiting for a punchline. When none is forthcoming, he offers:

‘Oh dear … sorry to hear it.’

‘Thanks.’

I don’t know if Gretton has a private life in any conventional sense, or if he sprouts a tail and corkscrews into an open manhole in a cloud of bright green special effects at five thirty p.m. This topic of conversation is certainly uncharted territory between us. The extent of our personal knowledge about each other is a) I have a fiancé, now past tense, and b) he’s originally from Carlisle. And that’s the way we both like it.

He shuffles his feet.

‘Heard anything about the airport heroin smuggling in 9 that kicks off today? Word is they hid it in colostomy bags.’

I shake my head.

‘For once they really could claim it was the good shit!’

He honks at this, broken engagement already forgotten.

‘I was going to stick with the honour killing in 1,’ I say, unsmiling. ‘Tell you what, you do the drugs, I’ll do the murder and we’ll compare notes at half time.’

Pete eyes me suspiciously, wondering what devious tactic this ‘mutually beneficial diplomacy’ might be.

‘Yeah, alright.’

Although I can get ground down by the bleak subject matter, I enjoy my job. I like being somewhere with clearly defined rules and roles. Whatever the grey areas in the evidence, the process is black and white. I’ve learned to read the language of the courtroom, predict the lulls and the flurries of action, interpret the Masonic whispers between counsel. I’ve built up a rapport with certain barristers, got expert at reading the faces of juries and quick at slipping out before any angry members of the public gallery can follow me and tell me they don’t want a story putting in the bloody paper.

As I swill the remains of the foul coffee, bin the cup and head towards Court 1, I hear a timid female voice behind me.

‘Excuse me? Are you Rachel Woodford?’

I turn to see a small girl with a halo of straw-coloured, frizzy hair, a slightly beaky nose and an anxious expression. In school uniform she could pass for twelve.

‘I’m the new reporter who’s shadowing you today,’ she says.

‘Ah, right.’ I rack my brains for her name, recall a conversation about her with news desk which now seems a geological era ago.

‘Zoe Clarke,’ she supplies.

‘Zoe, of course, sorry, I’m a bit brain-fugged this morning. I’m doing the murder trial today, want to join?’

‘Yes, thanks!’ She smiles as sunnily as if I had offered her a walking weekend in the Lakes.

‘Let’s go and watch people in wigs argue with each other then,’ I say. I point at the retreating Gretton. ‘And beware the sweaty man who comes in friendship and leaves with your story.’

Zoe laughs. She’ll learn.

5

At lunchtime, I open my laptop in the press room – a fancy title for a nicotine-stained windowless cell in the bowels of Crown Court, decorated with a wood veneer desk, a few chairs and a dented filing cabinet – and check my email. A message arrives from Mindy.

‘Can you talk?’

I type ‘Yes’ and hit send.

Mindy doesn’t like to email when she can talk, because she loves to talk, and she’s a phonetic speller. She used to put ‘Vwalah!’ in messages to myself and Caroline, which we assumed was a Hindu word, until under questioning it became clear she meant ‘Voilà’.

My phone starts buzzing.

‘Hi, Mind,’ I say, getting up and walking outside the press room door.

‘Do you have a flat yet?’

‘No,’ I sigh. ‘Keep looking on Rightmove and hoping the prices will magically plummet in a sudden property crash.’

‘You want city centre, right? Don’t mind renting?’

Rhys is buying me out of the house. I decided to use the money for a flat. Originally a city centre flat from which to enjoy single-woman cosmopolitan living, but the prices were a wake-up call. Mindy thinks I should rent for six months, get my bearings. Caroline thinks renting is dead money. Ivor says I can have his spare room and then he has a reason to finally kick out his flaky, noisy lodger Katya. As Mindy says, he could do that anyway if he ‘found his cojones’.

‘Yeees …?’ I say, warily. Mindy has a way of taking a sensible premise and expanding it into something entirely mental.

‘Call off the search. A buyer I work with is stinking rich and she’s off to Bombay for six months. She’s got a place in the Northern Quarter. I think it’s a converted cotton mill or something, and apparently it’s uh-may-zing. She wants a reliable flat-sitter and I said you were the most reliable person in the world and she said in that case she’ll do you a deal.’

‘Erm …’

Mindy quotes a monthly figure which is a fair amount of money. It’s not an unfeasible amount, and certainly not a lot for the kind of place I think she’s talking about. But: Mindy’s encroaching madness. It’ll probably come with an incontinent Maltipoo called Colonel Gad-Faffy who will only eat sushi-grade bluefin and has to be walked four times a day.

‘Do you want to come and see it with me, after work?’ Mindy continues. ‘She flies on Friday and a cousin of hers is interested. She says he’s a bit of a chang monster and she doesn’t trust him. So you’re front runner but you’re going to have to be quick.’

‘Chang monster?’

‘You know. Coke. Dickhead’s dust.’

‘Right.’

I think it through. I was really looking for something longer term than a fixed six months. Six months with option of renewal, I’d thought. But this might be a way to live the dream while I look for something more realistic.

‘Yeah, sure.’

‘Great! Meet you by Afflecks at half five?’

‘See you there.’

As I walk back into the press room, I realise why I’ve dragged my feet in moving out of the house, however uncomfortable it is. My decision to leave Rhys is about to turn from words into action, become real. Splitting equity, dividing up our worldly goods, coming-home-at-night-to-empty-rooms-and-a-big-yawning-maw-of-an-empty-future real. Part of me, a shrill, cowardly part, wants to scream: ‘Wait! Stop! I didn’t mean it! I want to get off!’ Motion sickness kicking in.

Yet I remember the text I got from Rhys a few days ago, saying, in what sounded as much like sorrow as anger: ‘I hope you’re looking for places because the end of living together like this can’t come fast enough for me.’

I flip my notebook open and wonder if I want another cow-shit coffee.

Zoe enters and hovers, giving off a static buzz of nerves.

‘Feel free to go and get something to eat. You can leave your things here if you like,’ I say.

‘Thanks.’ She puts her coat and bag down, and places her notebook on the table carefully.

‘Unless you fancy going to the pub for lunch?’ I continue, not sure where this magnanimity is coming from. Trying to atone for what I’ve done to Rhys, possibly. There will never be enough entries in the good deeds column of the Great Ledger of Life to offset that one.

‘That would be great!’

‘Give me five minutes and I’ll show you why The Castle has earned the accolade of “pub nearest court”.’

Zoe nods and sits down to transcribe her copy, longhand. I glance over while I’m typing. I knew it – her shorthand’s so perfectly formed you could photocopy it for textbook examples.

Gretton saunters in, squinting from me to Zoe and back again.

‘What’s this, Bring Your Daughter To Work Day?’

Zoe looks up, startled.

‘Welcome to the family,’ I say to Zoe. ‘Think of Gretton as the uncle who’d make you play horsey.’

6

I apologise to Zoe for not drinking alcohol when we get to the pub. I feel like I’m letting the profession down in moments like these. At every paper you always hear tales of great mythical beasts of olden times who could drink enough to sink battleships and still hit deadline, get up at first light the next day and do it all again. They’re legend, usually because they died in their fifties.

‘It’s soporific in court at the best of times, what with the heating and the droning on. If I hit the bottle I’d probably end up snoring,’ I say.

‘Oh, it’s OK, I’m a lightweight anyway,’ Zoe says. ‘I’ll have a Diet Coke as well.’

We scan the laminated menus on the bar, hearts sinking. The Castle’s menus have clearly been written by marketing managers who think they are conversant in the foreign language of ‘funny’. We try merely pointing at our selected lunch items to save our dignity. No dice with the morose barman.

‘I’ve got astigmatism,’ he says, as if I should know this.

‘Oh,’ I reply, flustered, trying for the last route out. ‘Then we’ll both have the Ploughman’s.’

‘Naked, Piggy or Extra Pickly?’

Dammit. ‘Piggy,’ I mumble, defeated. ‘Naked for her.’

‘You want that as a melt?’ he sighs, in a way that suggests most of the world’s problems are down to people like us wanting melts. We decide we do, but both pass on a squirt of the chef’s special sauce, given we’re not on nodding terms with him.

We make small talk, battling the octave range of Mariah Carey and multiple televisions, while two microwave-warm plates are banged down under our noses. As soon as Zoe finishes her meal, she says ‘Here’s what I wrote’, brushing crumbs off her hands and producing a spiral-bound notepad from her bag, flipping to the right page. ‘I wrote it out longhand.’

I feel a twinge of irritation at being expected to mentor while I’m still eating, but swallow it, along with a mouthful of rubbery cheese. I scan her story, braced for, if not car crash copy, a fender bender at the very least. But it’s good. In fact, it’s very fluid and confident for a first time.

‘This is good,’ I nod, and Zoe beams. ‘You’ve got the right angle, that the father and the uncle don’t deny that they went to see the boyfriend.’

‘What if something better comes up this afternoon? Do you stick with your first instinct?’

‘Possible but unlikely. The wheels turn pretty slowly. We probably won’t get on to the boyfriend’s evidence this afternoon.’

I hand Zoe’s notepad back to her.

‘So how long have you been here?’ she asks.

‘Too long. I went to uni here and did my training in Sheffield, then came to the Evening News as a trainee.’

‘Do you like court?’

‘I do, actually, yeah. I was always better at writing the stories than finding them, so this suits me. And the cases are usually interesting.’ I pause, worried I sound like the kind of ghoul who goes to inspect the notes on roadside flowers. ‘Obviously it’s nasty sometimes.’

‘What’s it like here?’ Zoe asks. ‘The news editor seems a bit scary.’

‘Oh yeah.’ With the flat of my knife, I push away a heap of gluey coleslaw that must’ve been on the plate when they heated it. ‘Managing Ken is like wrestling a crocodile. We all have the bite marks to show for it. Has he asked you the octuplets question yet?’

Zoe shakes her head.

‘A woman’s had octuplets, ninetuplets, whatever. You get the first hospital bedside interview, while she’s still whacked up on drugs. What’s the one question you don’t leave without asking?’

‘Er … did it hurt?’

‘Are you going to have any more? She’ll probably try to throw the bowl of grapes at you but that’s his point. You’re a journalist, always think like one. Look for the line.’

‘Right,’ Zoe’s brow furrows, ‘I’ll remember that.’

I feel that hopeless twinge of wanting to save someone the million cock-ups you made when you were new, and knowing they will make their own originals, and trying to save them anyway.

‘Be confident, don’t bullshit and if you do mess up and it’s going to come out, own up. Ken might still bawl at you but he’ll trust you next time when you say it’s not your fault. Lying’s his bête noire.’

‘Right.’

‘Don’t worry,’ I assure her. ‘It can be a bit overwhelming at first, then sooner or later, you start to recognise all human experience boils down to half a dozen various types of story, and you know exactly how desk will want them written. Which of course is when you’ve achieved the necessary cynicism, and should move on.’

‘Why did you want to be a journalist?’ Zoe asks.

‘Hah! Lois Lane.’

‘Seriously?’

‘Oh yes. The brunette’s brunette. Ballsy, stood up to her boss, had her own rooftop apartment and that floaty blue negligee. And she went out with Superman. My mum used to put the Christopher Reeve films on if I was off sick from school and I’d watch them on a loop. “You’ve got me, who’s got you?” Brilliant.’

‘Isn’t it weird how we make big decisions in life based on the strangest, most random things?’ Zoe says, sucking the straw in her Coke until it gurgles. ‘Like, maybe if your mum had put Batman on we wouldn’t be sat here right now.’

‘Hmm,’ I murmur indistinctly, and change the subject.

7

I see Mindy a mile off in her purple coat and red shoes. She looks like a burst of Bollywood sunshine compared to my kitchen-sink-drama drab black and white.

She calls it her Indian magpie tendencies – she can’t resist jewel colours and shiny things. The shiniest thing about her is always her hair. For as long as I’ve known Mindy, she’s used this 99p coconut shampoo that leaves her with a corona of light around her liquorice-black bob. I used it once and ended up with an NHS acrylic weave, made of hay.

She spots me and swings a key on a ribbon, like a hypnotist with a fob watch. ‘At last!’

Mindy isn’t kidding about it being central. Five minutes later we’re there, stood in front of a red-brick Victorian building which has changed from a temple of hard toil to a place of elegant lounging for the moneyed.

‘Fourth floor,’ Mindy says, gazing up. ‘Hopefully there’s a lift.’

There is, but it’s out of order, so we huff up several flights of stairs, heels pounding in time.

‘No parking,’ Mindy reminds me. ‘Is Rhys keeping the car?’

‘Oh yes. Given the way negotiations have gone so far, I’m glad we don’t have any pets or children.’

My mind flashes back to hours of my life I’d pay good money to have erased. We sat and worked out how to pick apart two totally meshed lives, me effectively saying ‘Have it, have it all!’ and Rhys snapping ‘Does it mean so little to you?’

Mindy slots the key in the lock of the anonymous looking Flat 21 and pushes the door open.

‘Shit the sheets,’ she breathes, reverentially. ‘She said it was nice but I didn’t know she meant this nice.’

We walk into the middle of a cavernous room with exposed brickwork walls. A desert of blonde wood flooring stretches out before us. Pools of honeyed light are cast here and there from some vertical paper lamps that look like alien pupae, or as if a member of Spinal Tap might tear their way out of them. The L-shaped sofa in the sitting area is an acre of snowy tundra, scattered with cushions in shades of ivory and beigey-bone. I mentally put a line through any meals involving soy sauce, red wine or flaky chocolate. That’s most Friday nights as I know them buggered.

Mindy and I wander around, going ‘woooh’ and pointing like zombies when we discover the wet room with glass sink, or the queen-sized bed with silvery silk coverlet, or the ice-cream-pink Smeg fridge. It’s like a home that a character in a post-watershed drama might inhabit. The sort of series where everyone is improbably good-looking and has insubstantial-sounding and yet lucrative jobs that leave plenty of time for leisurely brunching and furious rumping.

‘Not sure about that,’ I say, indicating the rug in front of the couch. It appears to be the skin of something that should be looking majestic in the Serengeti, not lying prone under a Heal’s coffee table. The coarse, hairy liver-coloured patches actually make me feel unwell. ‘It’s got a tail and everything. Brrrr.’

‘I’ll see if you can put that away,’ Mindy nods.

‘Tell her I’m allergic to … bison?’ It’s fake, I tell myself. Surely.

Standing in the middle of the living room, we do a few more open-mouthed 360-degree revolutions and I know Mindy’s planning a party already. In case we were in any doubt about the flat’s primary purpose, the word ‘PARTY’ has been spelt out in big burnished gold letters fixed to the wall. There’s also a Warholian Pop Art style print – an Indian girl with fearsome facial geometry gazes down imperiously in four colourways.

‘Is that her?’

Mindy joins me. ‘Oh yeah. Rupa does have an ego the size of the Arndale. See that nose?’

‘The one in the middle of her face?’

‘Uh-huh. Sweet sixteen present. Before …’

Mindy puts a finger on the bridge of her nose and makes a loop in the air, coming back to rest on her top lip.

‘Really?’ I feel a little guilty, discussing a woman’s augmentations in her own flat.

‘Yeah. Her dad’s, like, one of the top plastic surgeons in the country so she got a discount. So, what do you think to the flat, then?’ she says, somewhat redundantly.

‘I think it’s like that advert where they passed the vodka bottle across ordinary life and everything was more exciting looking through it.’

‘I remember that ad,’ Mindy says. ‘It made you think about people you’d slept with when you had beer goggles on though. Shall I tell her you’ll take it? Move in Saturday?’

‘What am I going to do with my things?’ I chew my lip, looking around. I was going to spoil the view by sitting down as it was.

‘Do you have a lot?’ Mindy asks.

‘Clothes and books. And … kitchen stuff.’

‘And furniture?’

‘Yes. A three-bed houseful.’

‘Do you really love it?’

I think about this. I quite like some of it. I have chosen it, after all. But in the event of a house fire, I couldn’t imagine protectively flinging myself on the occasional table nest or the tatty red Ikea couch as the flames licked higher.

‘Why I ask is, you could make a deal with Rhys to leave it. You said he’s keeping the house on? It’s going to be expensive for him to go and re-buy some of the bigger items, and a hassle. You could get money for them and then get things that suit wherever you end up buying. Or you could sell everything you own and buy one amazing piece, like an Eames lounger or a Conran egg chair!’

The Mindy paradox: sense and nonsense sharing a twin room – or even a bed, like Morecambe and not-so-Wise.

‘I suppose I could. It all depends how badly Rhys wants me out, versus how badly he wants to make life difficult for me. Too close to call.’

‘I can talk to him if you want.’

‘Thanks, but … I’ll give it a go first.’

We walk over to the window and the city rooftop panorama spreads out before us, lights winking on as dusk falls.

‘It’s so glamorous,’ Mindy sighs.

‘Too glamorous for me, maybe.’

‘Don’t do that Rachel thing of talking yourself out of something that could be good.’

‘Do I do that?’

‘A bit.’ Mindy puts an arm around me. ‘You need a change of scene.’

I put a reciprocal arm around her. ‘Thank you. What a scene.’

We study it in silence for a moment.

I point.

‘Hang on, is that …?’

‘What?’ Mindy squints.

‘… Swansea?’

‘Piss off.’

8

Mindy has to go home to work on reports for a meeting the next day so we say our goodbyes outside the flat. I’m walking to the bus home when I find my feet taking me towards the library. A few days earlier, loitering in Waterstones, it had occurred to me that if I decided to start learning Italian, I could revise at the library. Revise for the night classes I am definitely going to sign up for, soon. And then, if I ran into Ben, it’d be chance. Just fate, giving a tiny helpful shove.

As I approach, my posture gets better and my height increases by inches. I try to look neither left nor right at anyone as I walk in but can’t resist, my line of sight darting about like a petty con on a comedown. Central Library has the reverential atmosphere of a cathedral – it’s a place so serene and cerebral your IQ goes up by a few points simply by entering the building.

Inside, I unpack the Buongiorno Italia! books I happen to have on me, feeling intensely ridiculous. OK, so … wow, for a romantic language, this is harder work than I imagined. After ten minutes of intransitive verbs I’m feeling pretty intransitive myself. Let’s try social Italian: Booking a room … Making introductions … and my mind’s already wandering …

Ben knocked on my door bright and early on the first day of lectures, though not bright and early enough to pre-empt Caroline, who’s the one to call the lark a feathered layabout. I was anxiously turning my face a Scottish heather/English sunburn hue with a huge blusher brush, pouting into the tiny mirror nailed over my sink. Caroline stretched her flamingo legs out on my bed, cradling a vast quantity of tea in a Cup-a-Soup mug. It was a relief to discover that the girls in my halls of residence weren’t the demented, experienced, highly sexed party animals of my nightmares, but other nervous, homesick, excited teenagers, all dropped off with aid parcels of home comforts.

‘Who’s calling for you again?’ Caroline asked.

‘Someone on my course. He gave me my ID card.’

‘He? Is he nice?’

‘He seems very nice,’ I said, without thinking.

‘Nice nice?’

I debated whether to oblige her. We’d only been friends for a week and although she seemed sound, I didn’t want to abruptly discover otherwise when she started yodelling ‘My friend fancies yooooooo!’ across the union.

‘He’s quite nice, yeah,’ I said, with more take-it-or-leave-it insouciance.

‘How nice?’

‘Acceptable.’

‘I suppose I can’t expect you to do thorough reconnaissance,’ Caroline says, looking at the photo of me with Rhys on my desk.

It was taken in the pub, both squeezed into the frame while I held the camera above us. Our heads were leant against each other – his tangly black hair merging with my straight brown hair so it was hard to tell where he ended and I began. Rhys and Rachel. Rachel and Rhys. We alliterated, it was obviously meant to be. I’d daydreamed the two intertwined ‘Rs’ we’d have on our trendy wedding stationery invites, and would’ve put a firearm to my temple if he found out.

I glanced over at it too and felt a small tremor. Things were new and passionate, and unstable, like new and passionate things usually are, and we were forty miles apart. I’d been so elated when he’d said he wanted us to keep seeing each other.

We’d met a few months previously at my local. I used to go with my friends from sixth-form and we’d all sit with pints of snakebite and black and make moony eyes at the cool lads in a local band. They even had cars and jobs, their few extra years in age representing a chasm of worldly experience and maturity. This hero worship had gone on from afar for a long time. They were never short of female company and clearly content to keep a gaggle of schoolgirl groupies at arm’s length. Then one night I inadvertently found myself in a two-player game of call-and-reply on the jukebox. Every time I put a song on, Rhys’s selection straight after would pick up on the title. If I chose ‘Blue Monday’ he’d get up and play ‘True Blue’ and so on. (Rhys was in his ironic cheese phase. Shame it was long over by the time we really were planning our wedding.)

Eventually, after a lot of giggling, whispering and twenty-pence pieces, Rhys strode casually over to my table.

‘A woman of your taste deserves to be bought a drink.’

In a moment of sangfroid I’ve never since equalled, I found the words: ‘A man of your taste deserves to pay.’

My friends gasped, Rhys laughed, I had a Malibu and lemonade and a welcome for me and mine to join the corner of the pub they’d colonised. I couldn’t believe it, but Rhys seemed genuinely interested in me. The dynamic from then on was very much his man of the world to my wide-eyed ingénue. Later I’d ask him why he’d pursued me that night.

‘You were the prettiest girl in the place,’ he said. ‘And I had a lot of pocket shrapnel.’

There was a knock at my bedroom door and Caroline was up and over to answer it in a flash.

‘Sorry. Wrong room,’ I heard a male voice say.

‘No, right room,’ Caroline trilled, throwing the door open wider so Ben could see me, and vice versa.

‘Ah,’ Ben said, smiling. ‘I know there were a lot of freshers and cards yesterday but I was sure you weren’t blonde.’

Caroline simpered at him, trying to work out if this meant he preferred blondes or not. He looked at me, obviously wondering why I was the colour of a prawn and whether I was going to do introductions.

‘Caroline, Ben, Ben, Caroline,’ I said. ‘Shall we get going?’

Ben said ‘Hi’ and Caroline twittered ‘Hello!’ and I wondered if I wanted The First Person I’d Met In Halls to get it on with The First Person I’d Met On My Course. I had a suspicion I didn’t, on the basis it’d be tricky for me if it went badly and lonely for me if it went well.

‘Enjoy your day,’ Caroline said, with a hint of sexy languor that seemed at odds with it being breakfast time, trailing out of my door and back to her room.

I grabbed my bag and locked my door. We’d almost cleared the corridor without incident when Caroline called after me.

‘Oh, and Rachel, that thing we were discussing before? Acceptable wasn’t the right adjective. If you’re studying English, you should know that!’

‘Bye Caroline!’ I bellowed, feeling my stomach shoot down to my shoes.

‘What’s that about?’ Ben asked.

‘Nothing,’ I muttered, thinking I didn’t need the bloody blusher.

Surveying the Live-Aid-sized crowds milling around for the buses, Ben suggested we walk the mile to the university buildings. We kicked through yellow-brown leaf mulch as traffic rumbled past on Oxford Road, filling in the biographical gaps – where we were from, what A-levels we did, family, hobbies, miscellaneous.

Ben, a south Londoner, grew up with his mum and younger sister, his dad having done a bunk when he was ten years old. By the time we’d passed the building that looks like a giant concrete toast rack, I knew that he broke his leg falling off a wall, aged twelve. He spent so long laid up he’d had enough of daytime telly and read everything in the house, all the Folio Society classics and even his mum’s Catherine Cooksons, in desperation, before bribing his sister to go to the library for him. A splintered fibia became the bedrock of his enthusiasm for literature. I didn’t tell him that mine came from not being invited out to horse around on walls all that much.

‘You don’t sound very northern,’ he said, after I’d briefly described my roots.

‘This is a Sheffield accent, what do you expect? I bet you think the north starts at Leicester.’

He laughed. A pause.

‘My boyfriend says I better not come home with a Manc accent,’ I added.

‘He’s from Sheffield?’

‘Yes.’ I couldn’t help myself: ‘He’s in a band.’

‘Nice one.’

I noticed Ben’s respectful sincerity and that he didn’t make any cracks about relationships from home lasting as long as fresher flu, and I appreciated it.

‘You’re doing the long-distance thing?’

‘Yeah.’

‘Good luck to you. No way could I do that at our age.’

‘No?’ I asked.

‘This is the time to play the field and mess about. Don’t get me wrong, once I settle down I will be totally settled. But until then …’

‘You’ll collect lots of beer mats,’ I finished for him, and we grinned.

When we neared the university buildings, Ben got a folded piece of paper with a room plan out of his pocket. I noticed the creases were still sharp, whereas my equivalent was disintegrating like ancient parchment after too many nervous, sweaty-handed unfolding and re-foldings.

‘So, where is registration?’ he asked.

We bent our heads over it together, squinting at the fluorescent orange highlighted oblong, trying to orientate ourselves.

Ben rotated it, squinted some more. ‘Any ideas, Ronnie?’

My cheerfulness evaporated and I felt embarrassed. How many women did he meet yesterday?

‘It’s Rachel,’ I said, stiffly.

‘Always Ronnie to me.’

Our conversation about the stumpy passport photo came back to me and in relief and self-consciousness, I laughed too loudly. He must’ve seen my moment of uncertainty because there was a touch of relief in his laughter, too.

The best friendships usually steal up on you, you don’t remember their start point. But there was a definitive click at that moment that told me we weren’t going to politely peel apart as soon as we’d signed in and copied down our timetables.

I referred to the map again and as I leaned in I could smell the citrusy tang of whatever he’d washed with. I pointed confidently at a window.

‘There. Room C 11.’

Needless to say, I was wrong, and we were late.

9

Hope has leaked out of me, collected in a puddle at my feet and evaporated into the roof of Central Library, joining the collective human misery cloud in the earth’s atmosphere. No Ben, only the unavoidable evidence of how much I wanted to see him. On reflection, I’m not even sure Caroline wasn’t mistaken. She wears contacts and has started doing that middle-aged thing of not being able to tell the girls from the boys if they’re goths.

If Ben was here, it was only a flying visit for some obscure research purposes, and now he’s back in his well-appointed home, far, far away. Putting his Paul Smith doctor’s bag down in a black-and-white tiled hallway, leafing through his mail, calling out a hello to the equally high-powered honey he’s come home to. Blissfully unaware that a woman he used to know is such a pathetic mess she’s sitting a hundred and eighty miles away constantly re-reading the line: ‘Excuse me, which way to the Spanish Steps?’ in a bid to appear complicated and alluring.

I get out of my seat for a wander around the room, trying to look deeply cerebrally preoccupied and steeped in learning. The toffee-brown parquet floor is so highly polished it shimmers like a mirage. As I trail my fingers along the spines of books, I start as I see a brown-haired, possibly thirty-something man with his back to me. He’s sitting at a table tucked between the bookcases that line the edge of the room, so if you had an aerial view, they would look like the spokes inside a wheel.

It’s him. It’s him. Oh my God, it’s him.

My heart’s pulsing so hard it’s as if someone medically qualified has reached through my sawn ribs to squeeze it in a resuscitation attempt. I wander down past his seat and pretend to find a book of special interest as I draw level with his table. I pull it out and study it. In an unconvincing way, I pivot round absent-mindedly while I’m reading, so I’m facing him. It’s so unsubtle I might as well have shot a paper plane over to him and ducked. I risk a glance. The man looks up at me, adjusts rimless glasses.

It’s not him. A rucksack with neon flashes is propped near his feet, his trouser hems are circled with bicycle clips. I sag at the realisation that this must be who Caroline’s seen, too, and decide to gather my things. I pack up in seconds, no longer bothering to look appealing, on the final gamble that the law of sod will therefore produce him.

I shouldn’t have come here. I’m acting out of character and hyper-irrational in the post-traumatic stress of splitting up with Rhys. I don’t know what I’d say to Ben or why I’d want to see him. Actually, that’s not true. I know why I want to see him but the reasons don’t bear examination.

A clutch of people in fleeces and hats, who appear to be being given a guided tour, block my exit from the library. Like an impatient local, I retreat and double back round them. Deep in thought, I smack straight into someone coming the other direction.

‘Sorry,’ I say.

‘Sorry,’ he mutters back, in that reflexive British way where you’re apologetic that someone else has had to make an apology.

In order to perform the little tango of manoeuvring past each other, we exchange a distracted glance. There’s absolutely no way this man can be Ben. I’d know, I’d sense it if he was this close. I glance at his face anyway. It registers as ‘stranger’ then reforms into something familiar, with that oddly dull thud of revelation.

Oh Judas Priest! There he is. THERE HE IS! Plucked from my memory and here in the real world, in full colour HD. His hair’s slightly longer than the university years’ crop but still short enough to be work-smart, and they’re unmistakeably his features, the sight of them transporting me back a decade in an instant. And, despite the world’s longest ever build-up to a reappearance since Lord Lucan, Caroline’s right – he still takes air out of lungs.

He’s lost the slightly unformed, baby-fat look we all had back then, sharpening into something even more characterfully handsome. There’s a fan of light lines at the corner of each eye, the set of his mouth a little harder. His frame has filled out a little from the youthful lankiness of before.

It’s the strangest sensation, looking at someone who I know well and don’t know at all, at the same time. He’s staring too, although it’s the staring Catch-22: he could be staring because I’m staring. For an awful instant, I think either Ben’s not going to recognise me or – worse – pretend not to recognise me. But he doesn’t take flight. He opens his lips and there’s a pause, as if he has to remember how to engage his voice box and soft and hard palates to produce sounds.

‘… Rachel?’

‘Ben?’ (Like I haven’t given myself an unfair head start in this quiz.)

His brow stays furrowed in disbelief but he smiles, and a wave of relief and joy crashes over me.

‘Oh my God, I don’t believe it. How are you?’ he says, at a subdued volume, as if our voices are going to carry into the library upstairs.

‘I’m fine,’ I squeak. ‘How are you?’

‘I’m fine too. Mildly stunned right now, but otherwise fine.’

We laugh, eyes still wide: this is crazy. More than he knows.

‘Surreal,’ I agree, feeling my way tentatively back into a familiarity, like stumbling around your bedroom in the pitch dark, trying to remember where everything is. ‘You live in Manchester?’ he asks.

‘Yes. Sale. About to move into the centre. You?’

‘Yeah, Didsbury. Moved up from London last month.’

He brandishes a briefcase, like the Chancellor with the Budget.

‘I’m a boring arse lawyer now, would you believe.’

‘Really? You did one of those conversion courses?’

‘No. I blag it. Thought there was a saturation point when I’d seen enough TV dramas, I could go from there. Like Catch Me If You Can.’

He’s straight faced and I’m so shell-shocked that it takes me a second to process that this is humour.

‘Ah right,’ I nod. Then hurriedly: ‘I’m a journalist. Of sorts. Court reporter for the local paper.’

‘I knew you’d be the one to actually use that English degree.’

‘I wouldn’t say that. Not much call for opinions on Thomas Hardy when I’m covering the millionth car jacking.’

‘Why are you here?’

I’m startled by this, classic guilty conscience.

‘The library, I mean?’ Ben adds.

‘Oh, er, revision for my night class. Learning Italian,’ I say, liking how it sounds self-improving even as I cringe at the lie. ‘You?’

‘Exams. Bastard things never end. At least these mean I get paid more.’