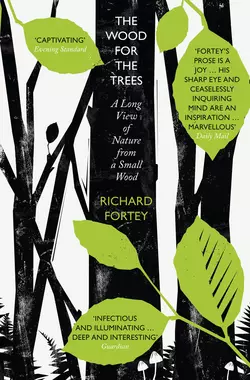

The Wood for the Trees: The Long View of Nature from a Small Wood

Richard Fortey

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Зарубежная образовательная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 930.44 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: From one of our greatest science writers, this biography of a beech-and-bluebell wood through diverse moods and changing seasons combines stunning natural history with the ancient history of the countryside to tell the full story of the British landscape.‘The woods are the great beauty of this country… A fine forest-like beech wood far more beautiful than anything else which we have seen in its vicinity’ is how John Stuart Mill described a small patch of beech-and bluebell woodland, buried deeply in the Chiltern Hills and now owned by Richard Fortey. Drawing upon a lifetime of scientific expertise and abiding love of nature, Fortey uses his small wood to tell a wider story of the ever-changing British landscape, human influence on the countryside over many centuries and the vital interactions between flora, fauna and fungi.The trees provide a majestic stage for woodland animals and plants to reveal their own stories. Fortey presents his wood as an interwoven collection of different habitats rich in species. His attention ranges from the beech and cherry trees that dominate the wood to the flints underfoot; the red kites and woodpeckers that soar overhead; the lichens, mosses and liverworts decorating the branches as well as the myriad species of spiders, moths, beetles and crane-flies. The 300 species of fungi identified in the wood capture his attention as much as familiar deer, shrews and dormice.Fortey is a naturalist who believes that all organisms are as interesting as human beings – and certainly more important than the observer. So this book is a close examination of nature and human history. He proves that poetic writing is compatible with scientific precision. The book is filled with details of living animals and plants, charting the passage of the seasons, visits by fellow enthusiasts; the play of light between branches; the influence of geology; and how woodland influences history, architecture and industry. On every page he shows how an intimate study of one small wood can reveal so much about the natural world and demonstrates his relish for the incomparable pleasures of discovery.