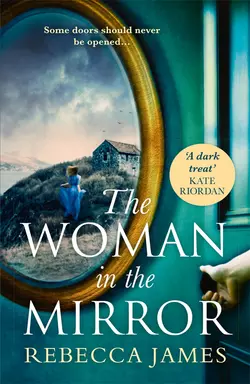

The Woman In The Mirror: A haunting gothic story of obsession, tinged with suspense

The Woman In The Mirror: A haunting gothic story of obsession, tinged with suspense

Rebecca James

‘A dark treat’ Kate Riordan, author of The Stranger

Haunting and moving, The Woman in the Mirror is a tale of obsession tinged with suspense, perfect for fans of Tracy Rees and Lulu Taylor.

You’ll be the woman of this house, next, miss. And you’ll like it.’

1947

Governess Alice Miller loves Winterbourne the moment she sees it. Towering over the Cornish cliffs, its dark corners and tall turrets promise that, if Alice can hide from her ghosts anywhere, it’s here.

And who better to play hide and seek with than twins Constance and Edmund? Angelic and motherless, they are perfect little companions.

2018

Adopted at birth, Rachel’s roots are a mystery. So, when a letter brings news of the death of an unknown relative, Constance de Grey, Rachel travels to Cornwall, vowing to uncover her past.

With each new arrival, something in Winterbourne stirs. It’s hiding in the paintings. It’s sitting on the stairs.

It’s waiting in a mirror, behind a locked door.

REBECCA JAMES was born in 1983. She worked in publishing for several years before leaving to write full-time, and is now the author of eight previous novels written under a pseudonym. Her favourite things are autumn walks, Argentinean red wine and curling up in the winter with a good old-fashioned ghost story. She lives in Bristol with her husband and two daughters.

Copyright (#ulink_f798638f-768a-5fa6-ada2-cd110c14214d)

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2018

Copyright © Rebecca James 2018

Rebecca James asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © June 2018 ISBN: 9781474073172

For the little soul

who wrote this book with me.

Shade of a shadow in the glass,

O set the crystal surface free!

Pass – as the fairer visions pass –

Nor ever more return, to be

The ghost of a distracted hour,

That heard me whisper, ‘I am she!’

MARY ELIZABETH COLERIDGE

Contents

Cover (#ud5cf124b-f1ba-5a81-a6b6-b05d8a8a54c3)

About the Author (#ulink_736f2e76-193c-5564-a488-b8a9058b343e)

Title Page (#ufa0be1cf-6f0b-5a20-bb34-7afdc4032afa)

Copyright (#ulink_c13c4588-6424-564c-84c9-ee606adb1e73)

Dedication (#u65c902a6-56b7-540e-9202-329a018fc74b)

Prologue (#ulink_d9a50190-38cf-565f-96bc-9409138cef1e)

Chapter 1 (#ulink_487a60a7-c6b1-5f2b-88e7-759061d0a74b)

Chapter 2 (#ulink_3d6305de-84f7-5962-9cfa-2b55e38db319)

Chapter 3 (#ulink_87dedeae-dd10-5785-9ffc-d969d4a412f4)

Chapter 4 (#ulink_2d3da5da-5537-599b-83a2-f28e8701afb1)

Chapter 5 (#ulink_2e93fe7a-4519-5647-8001-33156bfd6975)

Chapter 6 (#ulink_1f22fe70-49fa-5089-9448-c4a62a9beaa9)

Chapter 7 (#ulink_1882741b-9fa9-5da2-ad79-89086de50519)

Chapter 8 (#ulink_7d4b508c-e931-5000-adfb-8f327db80916)

Chapter 9 (#ulink_7c451664-d73c-5b26-8638-1d7fe3278e6b)

Chapter 10 (#ulink_ca1d94f1-a9a0-5f46-9538-251a3cfb1c61)

Chapter 11 (#ulink_a99627df-d26b-5655-9154-ec8897c5d13a)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#ulink_45a69dc5-183c-5bc9-b173-0c326c41ae69)

Cornwall, winter 1806

Listen! Can you hear it?

There, right there. Listen. You are not listening. Listen hard.

Listen harder.

I hear them before I see them. Their shouts come from across the hill, calling my name, calling me Witch. They come with their spikes and flames, their red mouths and their black intent. They say I am the one to fear, but the fear is with them. Fear is in them. It has no need of me. Their fear will catch them at the final hour.

Shadows crawl over the moors, spreading dark against dark. Their torches dance, lit from the fire at the barn. Burn her! Drown her! Smoke her from her hole!

Witch.

It is not safe for me here. They will touch their fires to my home and I will perish inside. So I escape into the night, their steps bleeding close on the wind like a dread gallop. Down the cliffs, low to the ground, the sky watches, patient and indifferent. Stars are frozen. Moon observes. I cannot turn back: my home is lost.

At the end I will put myself there again, sitting by my hearth and staring at the painting on the wall. It is the painting I did for him but never gave him, a likeness of my house for he had admired it so; he had said what a perfect spot it held, high on the cliffs, a sweet little cottage circled by hay and firs. Oh, for those first days of innocence! For those days of blind hope, before he turned me away. On the night I planned to bestow the painting on him, he broke my heart. The gift I had meant for him remained with me, just as did every other part I imagined I would share.

I never thought I would be a woman for love, or a woman to be loved.

A woman should always trust herself.

What will remain at my home, after I am gone? What will he keep and what will he burn? I fear for my looking glass, my beloved mirror. I pray that it survives, for I wonder if a piece of me, however small, might survive with it.

Ivan. My love. How could you?

I shall never know. I will never understand. What is the point, now, in any case? Ivan de Grey betrayed me. I believed that he worshipped me, I swallowed his deceits and oh, it hurts, it hurts, to think of his arms around me…

Now they have built their case against me. They have shaped their fight and honed their resolve. There is nothing I can say or do; to protest confirms my fate.

I spill down the cliff path. I know it well enough in the dark. Brambles tear my skin and eyes; blood tastes sour in my mouth. I stumble, holding mud and air. My head hits a rock, sharp, hard, and I fall until a pain pulls me back, my hair caught on a stalk. For a moment, I lie still. Thunder, thunder, thunder. I gaze up at the night, the cool white pearl of the moon. I wish I were an animal. I wish I were a wolf. I wish I would transform, and be waiting for them when they come over the edge. I would leap at them with my jaws thrown wide.

But I am a woman. Not a wolf. Perhaps I am something in between.

Run.

I meet the sea, which has swallowed the sand completely. It foams around my ankles and I wade through it, salt burning the cuts on my legs. Ivan long ago decided I was marked. He saw the red on my body and the rest was easy. He told his friends and those friends told their enemies, and all are united in the crusade. Witch.

All he had to do was to make her believe in his love.

Love.

Rotten, stinking, hated love. Love is for fools, bound for hell.

I detest its creeping treacheries. I resent the shell it made of me. My weakness to be wanted, my pathetic, throbbing heart…

There is comfort in knowing that while I die, my hatred lives on. My hatred remains here, on this coast, in this sea and under this sky. My hatred remains.

I trust it with my vengeance, for vengeance I will take.

The water pulls me to my knees, black and thrashing and soaking my dress.

I turn to shore. High on the hill is a bright, living blaze. The men stride towards me, stride through the sea. I will not go with them. I will go on my own, willingly. I will swim to the deep and deeper still. I will picture my home as I drown.

I crawl into the wild dark.

A hand grabs my ankle and pulls me down.

Chapter 1 (#ulink_bdead6eb-47b6-51cc-837a-97abf3021c20)

London, 1947

‘Alice Miller – for heaven’s sake, wake up.’

It might be Mrs Wilson’s uppity remark that jolts me out of my eleven o’clock reverie, or else it’s the warm muzzle of the Quakers Oatley & Sons’ resident Red Setter as it nudges hotly against my lap, for it’s hard to know which happens first.

‘I’m awake,’ I tell her, finding the dog’s warm ears under my desk and working them through my fingers; Jasper breathes contentedly through his nose and his tail bangs on the floor. ‘Can’t you see my eyes are open?’

Mrs Wilson, the firm’s stuffy administrator, draws deeply on her cigarette, sucking in her cheeks. She dispels a plume of smoke before grinding the cigarette out in an ashtray. She pushes her glasses on to the bridge of her nose.

‘I wouldn’t suggest for a moment, Miss Miller, that your eyes being open has the slightest thing to do with it.’ Her fingers clack-clack on the typewriter. ‘It doesn’t take a fool to see that you’re miles away. As usual.’

If I were able to dispute the accusation, I would. But she’s right. There is little about being a solicitor’s secretary that I find stimulating, and my memories too often call me back. This is not living, as I have known living. Haven’t we all known living – and dying – in ways impossible to articulate? But to look in Jean Wilson’s eyes, just two years after wartime, as flat and grey as the city streets seem to me now, it’s as if that world might never have existed; as if it had been just one of my daydreams. I wonder what Mrs Wilson lost during those years. It is easy for one to feel as though one’s own loss overtakes all others’ – but then one remembers: mine is a lone story, a single note in a piece of music that, if played back many years from now, would be obscured by the orchestra that surrounds it.

Jasper pads out from under the desk and settles on a rug by the window. Through it, I hear the noisy brakes of a bus and a car tooting its horn.

The telephone rings. ‘Good morning, Quakers Oatley?’

We are expecting a call from an irksome client but to my surprise it is not he. For a moment, I hear the crackle of the line and the faint echo of another exchange, before a smart voice introduces itself. My grip tightens. I’m quiet for long enough that Mrs Wilson’s interest is aroused. She glances at me over the top of her spectacles.

‘Of course,’ I say, once I’ve taken in all that he’s said. ‘I’ll be with you right away.’

I replace the telephone, retrieve my coat and open the door.

‘Where are you going?’

‘Goodbye, Mrs Wilson.’ I put on my coat. ‘Goodbye, Jasper.’

It is the last time I will see either of them.

*

The Tube still smells as it did in the war – fusty, sour, hot with bodies. Next to me on the platform is a woman with her children; she smacks one of them on the hand and tells him off, then pulls both to her when the train comes in. I imagine her down here during the Blitz, when they were babies, holding them close while the sky fell down.

I take the train to Marble Arch, repeating the address as I go. The building is closer than I think and I’m here early, so I step into a café next door and order a mug of tea. I drink it slowly, still wearing my hat. A man at the table next to me slices his fried egg on toast so that the yoke bursts over his plate and an orange bead lands on the greasy, chequered oilcloth. He dabs it with his finger.

I’ve kept the advertisement in my handbag for a month. I didn’t think anything would come of it; the opportunity seemed too niche, too unlikely, too convenient. GOVERNESS REQUIRED, FAMILY HALL NR. POLCREATH, IMMEDIATE APPOINTMENT. I spied it during a sandwich break, in the back of the county paper Mrs Wilson brought home from a long weekend in the South West.

I unfold it and read it again. There really isn’t any other information, nothing about the people I would be working for or for how long the position might be. I question if this isn’t what drew me towards the prospect in the first place. My life used to be full of uncertainties: each day was uncertain, each sunrise and sunset one that we didn’t expect to see; each night, while we waited for the bombs to drop and the gunfire to start, was extra time we had somehow stumbled into. Uncertainty kept me alive, knowing that the moment I was in couldn’t possibly last for ever and the next would soon be here, a moment of change, of newness, the ground shifting beneath my feet and moving me forward. At Quakers Oatley, the ground sticks fast, so fast I feel myself drowning.

The tea turns tepid, the deep cracked brown of a terracotta pot, and a fleck of milk powder floats depressingly on its surface. The man next to me grins, flips out his newspaper: India Wins Independence: British Rule Ends. I sense him about to speak and so stand before he can, buttoning my coat and checking my reflection in the smeared window. I pull open the café door, its chime offering a weak ring.

There it is, then. No. 46. Across the road, the genteel townhouse bears down, its glossy black door and polished copper bell push like a delicately wrapped present that my fumbling fingers are desperate, yet fearful, to open. Before we begin, it has me on the back foot. I need it more than it needs me. This job is my ticket out of London, away from the past, away from my secrets. This job is escape.

*

‘Welcome, Miss Miller. Do please sit down.’

I peel off my gloves and set them neatly on the desk before changing my mind and scooping them into my bag. I set the bag on my lap, then have nowhere to put my hands, so I place the bag on the floor, next to my ankles.

He doesn’t appear to notice this display, or perhaps he is too polite to acknowledge it. Instead, he takes a file from the drawer and flicks through it for several moments. The top of his head, as he bends, is bald, and clean as a marble.

‘Thank you for meeting us at short notice,’ he says, with a quick smile. ‘My client, as you’ll understand, prefers to be discreet, and often that means securing results swiftly. We would prefer to resolve the appointment as soon as possible.’

‘Of course.’

‘You have experience with children?’

‘I used to nanny our neighbours’ infants, before the war.’

He nods. ‘My client’s children require tutelage as well as pastoral care. We are concerned with the curriculum but also with a comprehensive education in nature, the arts, sports and games – and, naturally, refinement of etiquette and propriety.’

I sit straighter. ‘Naturally.’

‘The twins are eight years old.’ His eyes meet mine for the first time, sharp and glassy as a crow’s.

‘Very good.’

‘I’m afraid this isn’t the sort of position you can abandon after a month,’ he says. ‘If you find it a challenge, you can begin your instruction by teaching these children the knack of perseverance.’ He puts his fingers together. ‘I mention this because my client lost his last governess suddenly and without warning.’

‘Oh.’

‘As a widower, he has understandably struggled. These are difficult times.’

I’m surprised. ‘Did his wife die recently?’

Immediately I know I have spoken out of turn. I am not here to question this man; he is here to question me. My interest is unwelcome.

‘Tell me, Miss Miller,’ he says, bypassing my enquiry with ease, ‘what occupation did you hold during the war?’

‘I volunteered with the WVS.’

The man teases the end of his moustache. ‘Nurturing yet capable: would that be a fair assessment?’

‘I’d suggest the two aren’t mutually exclusive.’

He writes something down.

‘Have you always lived in London?’

‘I grew up in Surrey.’

‘And attended which school…?’

‘Burstead.’

His eyebrow snags, impressed but not liking to show it. I know my education was among the finest in the country. My mother was schooled at Burstead, and my grandmother before that. There was never any question that my parents would send me there. I tighten my fists in my lap, remembering my father’s face over that Sunday lunch in 1940. The ticking of the mantle clock, the shaft of winter sunlight that bounced off the table, the smell of burned fruit crumble… His rage when I told him what I had done. That the education they had bought for me had instead brought a nightmare to their door. The sound of smashing glass as my mother walked in, letting the tumbler fall, shattering into a thousand splinters on the treacle-coloured carpet.

He clears his throat, tapping the page with his pen. I see my own handwriting.

‘In your letter,’ he says, ‘you say you are keen to move away from the city. Why?’

‘Aren’t we all?’ I answer a little indecorously, because this is easy, this is what he expects to hear. ‘I would never care to repeat the things I have seen or done over the past six years. The city holds no magic for me any more.’

He sees my automatic answer for what it is.

‘But you, personally,’ he presses, those eyes training into me again. ‘I am interested in what makes you want to leave.’

A moment passes, an open door, the person on each side questioning if the other will walk through – before it closes. The man sits forward.

‘You might deem me improper,’ he says, ‘but my inquests are made purely on my client’s behalf. We understand that the setting of your new appointment is a far cry from the capital. Are you used to isolation, Miss Miller? Are you accustomed to being on your own?’

‘I am very comfortable on my own.’

‘My client needs to know if you have the vigour for it. As I said previously, he does not wish to be hiring a third governess in a few weeks’ time.’

‘I’ve no doubt.’

‘Therefore, if you will forgive my impudence, could you reassure us that you have no medical history of mental disturbances?’

‘Disturbances?’

‘Depressive episodes, attacks of anxiety, that sort of thing.’

I pause. ‘No.’

‘You cannot reassure us, or you can that you haven’t?’

For the first time, there is the trace of a smile. I am almost there. Almost. I don’t have to tell him the truth. I don’t have to tell him anything.

‘I can reassure you that I am perfectly well,’ I say, and it trips off my tongue as smoothly as my name.

The man assesses me, then squares the paper in front of him and replaces it in its folder. When he leans back in his chair, I hear the creak of leather.

‘Very well, Miss Miller,’ he says. ‘My client entrusts me with the authority to hire at will in light of my appraisal of an applicant’s suitability, and I am pleased to offer you the position of governess at the Polcreath estate with immediate effect.’

I rein in my delight. ‘Thank you.’

‘Before you accept, is there anything you would like to ask us?’

‘Your client’s name, and the name of the house.’

‘Then I must insist on your signature.’

He slides a piece of paper across the desk, a contract of sorts, listing my start date as this coming week, the broad terms of my responsibilities towards the children, and that my bed and board will be provided. There is a dotted line at the foot, awaiting my pen. ‘I understand it is unorthodox,’ he says, ‘but my client is a private man. We need assurance of your allegiance before I’m permitted to give details.’

‘But until I have details I have little idea what I am signing.’

The man holds his hands up, as if helpless. I wait a moment, but there is never any hesitation in my mind. I collect the pen and sign my name.

Chapter 2 (#ulink_8298e578-b0c4-53b3-9fa6-a41436d20761)

My train pulls into Polcreath Station at four o’clock on Sunday. The warmth has gone out of the day and a rich, autumn sun sits low on the horizon, casting the land in a burned harvest glow. I’m quick to see the car, but then it’s hard to miss, a smart, black Rolls-Royce whose white wheels gleam like bones in the fading light.

A man greets me, short, middle-aged, fair. ‘Miss Miller?’

‘How do you do.’

He lifts my bags into the car then opens the rear door for me. Up close, the Rolls is more decayed than it first appeared. Its paintwork is peeling and inside the upholstery is fissured and coming away from the seat frames. There is the smell of old cigarettes and petrol. It takes the chauffeur a moment to start the engine.

‘I’m Tom, Winterbourne’s houseman,’ he says, when I ask him: not a chauffeur after all, then. ‘I’ll turn my hand to anything.’ He has a gentle Northern accent and a friendly, easy manner. ‘There’s not many of us – just me and Cook. And you, now, of course. The house can’t afford anyone else, though goodness knows we need it. We’re mighty excited to have you joining us, miss. Winterbourne always seems darker at this time of year, when the evenings draw in and the light starts to go. The more company the better, I say.’

‘Please, call me Alice.’

‘Right you are, miss.’

I smile. ‘Is it far to Winterbourne?’

‘Not far. Over the bluff. The sea makes it seem further – there’s a lot of sea. Are you used to the sea, miss?’

‘Not very. One or two holidays as a child.’

‘The sea’s as much a part of Winterbourne as its roof and walls. I expect that sounds daft to a city lady like yourself, but there it is. You can see the sea from every window, did they tell you that?’

‘They didn’t tell me much about anything.’

Tom crunches the gears. ‘This car’s a bad lot. The captain would never part with it, but really we’d be better off with a horse and cart, at the rate this thing goes.’

‘More comfortable, though, I’d wager.’ Although I’m being generous: with every bump and rut in the road the car squeaks in protest, and the springs in my seat dig painfully into my thighs. The short distance Tom promised is ever lengthening. In time we come off the road and on to a track, on either side of which the countryside spreads, a swathe of dark green that eventually gives way, if I squint into the distance, to a flat sheet of grey water.

‘The moors look tame from here,’ says Tom, with a quick glance over his shoulder, ‘but wait till we reach the cliffs. It’s a sheer drop there – ground beneath your feet one moment, then nothing. You’ve got to be careful, miss. The mists that come in off the sea are solid. Some days you can’t see more than a foot or two in front, you can’t see a thing. All you’ve got to go on is the sound of the sea, but if you lose your bearings with that, one wrong step and you’re gone. Winterbourne’s right on the bluff. Some people say it’s the second lighthouse at Polcreath.’

‘How long have you worked for the captain?’

‘Since before the war. I knew him when he was a…different sort of person. The war changed people, didn’t it? Just because you have a title, or a place like Winterbourne, it doesn’t spare you. He was hurt in France; it’s been hard for him, an able-bodied man like that suddenly made a cripple. Did the war change you, miss?’

I focus on the horizon, an expanse of steel coming ever closer, and concentrate on the clean line of it so intently that I can’t think of anything else. ‘Of course.’

‘Between you and me, I could likely find better-paid employment elsewhere, but I’ve got loyalty for Winterbourne, and for the captain. My mother used to say that you’re nothing without your friends. The captain would never say I was a friend, but he doesn’t say a lot of things that he might really mean.’

‘How tragic that he lost his wife.’

‘Indeed, miss.’ There’s a laden silence. ‘But we don’t speak about that.’

I sit back. I had hoped that Tom’s loquaciousness might lend itself to a confidence, but seemingly not on this matter. Two people now have refused to speak to me about the former woman of the house. What happened to her?

I am expecting us to come across the Hall suddenly, to catch a quick glimpse of it between trees or to swing abruptly through the park gates, but instead I spot it first as a ragged smudge on the hill. That’s how it appears – as an inkblot the size of my thumb, spilled in water, its edges seeming to fall away or dissolve into air. There is something about its position, elevated and alone, that reminds me of a fortress in a storybook, or of a drawing of a haunted house, its black silhouette set starkly against the deepening orange of the sky. As we approach, I begin to make out its features. To say that Winterbourne is an extreme-looking house would be an understatement.

It’s hard to imagine a more dramatic façade. The place instantly brings to mind an imposing religious house – a Parisian cathedral, perhaps, decorated with gaping arches and delicate spires. Turrets thrust skyward, and to the east the blunt teeth of a battlement crown remind me of a game of chess. Plunging gargoyles are laced around its many necks, long and thin, jutting, as if leaping from the building’s skin. Lancet windows, too many to count, adorn the exterior, and set on the western front is what appears to be a chapel. I was scarcely aware of having entered the park, and it strikes me that we must have crossed into it a while ago; that the land we’ve been driving on all this time belongs to Winterbourne.

Gnarled trees creep out of the drowning afternoon. To our left, away from the sea, spreads a wild, dark wood, dense with firs and the soft black mystery of how it feels to be lost, away from home, when you are a child and the night draws close. On the other, the sea is a wide-eyed stare, lighter and smoother now we are near, like pearls held in a cold hand. I see what Tom meant about the drop from the cliffs: the land sweeps up and away from the hall, a brief sharp lip like the crest of a wave, and then it is a four-hundred-foot plummet to the rocks. Further still into that unblinking spread I detect Polcreath Point, the tower light, a mile or so from the shore.

‘Here we are, miss.’ Tom turns the Rolls a final time and we embark up the final stretch towards the house, a narrow track between overgrown topiary. Leafy fingers drag against the windows, and the car rocks over a series of potholes that propels my vanity case into the foothold. At last we emerge into an oval of gravel, at the centre of which is an unkempt planter, tangled with weeds.

‘Winterbourne Hall.’

I gaze up at my new lodgings, and imagine how my arrival must look. A throbbing engine, a lonely car – and a woman, peering skyward, her hand poised to open the door, and some slight switch of nameless apprehension that makes her pause.

*

The first thing I notice is the smell. It isn’t unpleasant, merely unusual, a liturgical smell like the inside of a church: wood, stone and burning candles.

There are no candles burning. The entrance is gloomy, lit by a flickering candelabrum. ‘Ticky generator,’ explains Tom, taking off his cap. ‘We use fires, mostly.’ I look up at the chandelier, its bulbs bruised with dust and casting an uncertain glow that sends tapered shadows across the walls. The ceiling is ribbed and vaulted, like the roof of a basilica, but its decorations are bleached and crumbled. A staircase climbs ahead of me, a faded scarlet runner up its centre, bolted in place by gold pins. Some of the pins are missing and the carpet frays up against the wood like a rabbit’s tail. On the upper walls, a trio of hangings in red and bronze sits alongside twisting metal sconces, better suited to a Transylvanian castle than to a declining Cornish home. There is a large stone fireplace, coated in soot, and several items of heavy Elizabethan furniture positioned in alcoves: elaborate dark-wood chairs, an occasional table, and a hulking chest with edges wreathed in nail heads.

On the landing above, I see closed doors, set with gothic forging. The windows are heavily draped in velvet, with tasselled tiebacks. Dozens of eyes watch me watching. Paintings of the captain’s ancestors bear down from every facet.

For a moment I have the uncanny sense of having been here before – then I place the connection. The headmaster’s study at Burstead. How, when a girl was called in for a flogging, she would be surrounded by an army of onlookers – those men, tyrants past, with their shining eyes and satisfied smirks, their portraits as immovable as the headmaster’s intention, and she would stand in the red punitive glow of the stained-glass window and bite her lip while the first lash came…

Afterwards, when they couldn’t decide how the tragedy had happened, they brought us all in for a whipping; perhaps they thought the belt would draw it out of us as cleanly as it drew blood to the skin. The difficulty was that nobody except me knew the truth. Nobody else had been there. They sensed a secret, dark and dreadful, rippling through the dormitories like an electrical charge, but I was the only girl who knew and I wasn’t about to share it. So I kept my lips shut and I let the lashes come for me and for the others, and time passed and term ended and school finished not long after that.

I blink, and take my gloves off.

‘Where are the children?’ I ask. ‘I should like to introduce myself.’

Tom gives me a strange look. ‘The captain asked us to settle you in first, miss. The twins can get overexcited. They like to play games.’

‘Well, they’re children, aren’t they?’

He pauses, as if my query might have some other answer.

‘What happened to their previous governess? The woman before me?’

‘She left,’ Tom replies, too quickly and smoothly for it to be the truth. ‘One morning, suddenly. We had no warning, miss, honestly. She sent word days later – a family emergency. She was mighty sad about it, hated letting the captain down. We all of us hate to let the captain down. It’d be horrible if he was let down again, wouldn’t it, miss? After the effort he’s gone to, to bring you down here. There’s only so much a man can take. The captain said there was no way round it, and the world exists outside Winterbourne whether we like it or not. Because you do feel that way, miss, here, after a while. Like Winterbourne is all there is, just the house and sea. You find you don’t need anything else.’ His expression is unfathomable, doggedly loyal.

‘Do the children miss her terribly?’ I am not sure if I am talking about the governess or the children’s mother: this pair of doomed women, for a moment, seem bound in a fundamental, terrifying way, but the thought flits free before I can catch it.

‘Of course they do,’ Tom says. ‘But they’ll warm to you even better.’

I’m about to ask my predecessor’s name – it seems important to know it – when there is a noise on the staircase: a shuffle of footsteps, a slow, lilting gait, punctuated by the unmistakable point of a cane. When my employer comes into view, I take a step back. I have never seen anyone in my life who looks like this.

‘The new governess,’ he says bluntly, twisting his cane into the stair.

For a moment I forget my name.

‘Alice Miller,’ I say at last.

The man steps forward, into a pit of shadow so that I can no longer see his face. Captain Jonathan de Grey. The name that has followed me from London, from that interview that seems like years ago in spite of it being days – from before then, even, if that were possible. ‘I trust you had a good journey,’ he says, in a peculiar, remote voice. ‘We’re very pleased that you’re here. Very pleased indeed.’

Chapter 3 (#ulink_fe5085a2-89b4-5012-873a-bce5f6b71f1a)

New York, present day

Rachel Wright stepped on to the podium to address her guests. Pride filled her as she took in the gallery launch, the people mingling, the inspiring artworks and the sheer transformation of the space she had purchased six months ago from rundown warehouse to edgy exhibition. Immediately, she felt his eyes on her.

‘Ladies and gentlemen,’ Paul, her assistant, announced as he tapped the microphone. ‘May I introduce the woman responsible for tonight: Founder and Director of the Square Peg Gallery – Rachel Wright!’ Paul smiled as he led the applause. He wanted to please her. Everyone did. Rachel commanded respect. Little was known about her private life and the care with which she protected it was a point of staunch admiration. Paul and the others knew about the big thing, of course. But nobody mentioned it.

‘Thank you all for being here tonight,’ Rachel began. ‘And thanks especially to our sponsors, without whom none of this would be possible – in particular White Label Inc. and G&V Assets.’ She deliberately named his firm second; it was a stupid power thing. More applause, for them or for her, it didn’t matter. She needed their funds and they needed her association. She’d said as much in her pitch. Where was their commitment to community culture? Were their rivals delivering on social responsibility? She remembered launching her petition in his boardroom, the way his black eyes had trained into her as they trained into her now, challenging her. How did he always manage it? Rachel could present to sponsors from here to Milan, could sit opposite the greatest creatives in the world, but with him, well, he made her feel the spotlight. It was the excitement of their arrangement, she supposed.

‘If this gallery hasn’t stopped to breathe, then neither have I,’ Rachel told her audience, thinking of the three hours’ sleep she had grown accustomed to snatching; of the caffeine she lived off and the cigarettes she was trying to give up but that sometimes pushed her that extra hour into the night, of the determination – ‘my mother had another word for it,’ she joked – that took an idea out of one’s head and made it a reality; of the team she’d had behind her; of her Upper West Side apartment that she never spent any time in and that had become overtaken by work. Talking about the gallery was like talking about herself, for she had given everything to it over the past eighteen months. Art was her passion and her purpose. She had always found sanctuary in it, in its possibility and lack of boundary, in its subjectivity and beauty, in its strength to innovate and energise, to change minds and start dialogues. Since she could remember, she’d been happiest staring into a painting or admiring a sculpture, imagining the stories that went into it and, in doing so, she was able to forget her own.

As always when Rachel spoke in front of big crowds, she wound up feeling they were waiting for more. Perhaps they were. They knew, after all, what had happened to her back in 2012. It had been in the papers, talked about over breakfast tables. Did they expect her to reference it? She wondered, sometimes, if she should. That maybe if she mentioned it once, that would be enough. That would sate their curiosity about whether it was an event she acknowledged and accepted, an event she had dealt with. Perhaps she didn’t ever bring it up because she hadn’t dealt with it.

Her speech closed to the sound of rapturous appreciation. Rachel dared herself to find his face. It wasn’t difficult. She could just imagine the scent of his aftershave, which she caught when they embraced, just inside the angle of his shirt collar.

*

Of course he followed her back from the launch. Mutually they had decided not to be seen together in public. On the surface neither wanted their position to be compromised – his investment muddied the waters somewhat – but deep down it was their shared reluctance to commit. A no-strings arrangement suited both fine. Secret liaisons at her apartment or his heightened the thrill. Being linked officially made it too serious, too much of a fact. Rachel wasn’t ready for that. She liked the emotional distance.

She was stepping into the shower when she heard the buzzer go.

‘Aaron.’ She answered the door in her gown. ‘It’s two a.m. Can’t you sleep?’

He grinned. ‘Not without you.’ He leaned in and she turned her face away, just a fraction, to tease him, even though she knew she would let herself be kissed.

‘You were sensational tonight,’ he said, his arms looping round her waist.

‘Thank you.’

‘I mean it. I was impressed.’

She could never tell how sincere he was being. Aaron Grewal was arrogant and proud (as she suspected were many multimillionaires), and she had a reasonable inkling he slept with other women. But she didn’t care. This wasn’t about heart and soul; it was about danger and distraction. Aaron was different to what she was used to…to what was missing. He was like her late nights, her coffee, her deadlines, a quick fix to get through, nothing permanent or serious, nothing it would hurt to lose.

Afterwards, they lay in each other’s arms. It was nice to be held, to hear the warm beat of another person’s heart. When she’d won the pitch from Aaron’s firm, they’d told her she was one of the strongest candidates they’d seen. The word had stayed with her, become part of why she’d been drawn into romance with Aaron in the first place. He saw her strength and recognised it. Strength was the reason she was still here. It was how she’d got ahead, being decisive, being convinced: it was how she’d survived.

In the glow of the streetlight, Rachel made out the room around her: a student’s room, a rented room, a room lived in for hours at a time. Interspersed with her plans for the gallery, drawings, reports and journals filled with sketches and emails and wish lists, was a litter of empty cups, perfumes, piled up books, pictures that never made it on to the walls, propped up against wash racks, clothes strewn across the floor, handbags and pill packets and phone chargers…

There were no photographs. Aaron had commented on it when he’d first come over. No framed family, no memories, nothing personal. It hadn’t been intentional, just how things were. She couldn’t help it. The past was a stranger.

‘Goodnight, Success Story,’ Aaron murmured, kissing the top of her head.

She smiled into his chest, feeling the urge to cry. Exhaustion, that was all. And an expression of tenderness she had long learned to live without, so that when she received it, it hurt a little. Rachel had cried a lot at the start of her life, and she had cried a lot in 2012, but she hadn’t cried since. As a rule she didn’t cry. Instead she surrounded herself with noise and lights, with anything but quiet and dark.

It took ages to fall asleep. She would manage a couple of hours and that was what she preferred: a brief sliver of quiet before the day drew her into its comforting, busy embrace. And yet the shorter the sleep, the deeper her dreams… Always they came in bursts, the same one on a cycle for weeks at a time. This one had lasted longer than most. Rachel felt herself floating in a familiar space, inexplicable, tantalising, as known to her as her skin yet as alien as the stars: a dimly lit passage in a huge, impersonal house, a moon-bathed window, coarse floorboards beneath her naked feet. This faraway place called her, whispering, whispering, This is where you belong.

Chapter 4 (#ulink_22acd341-fcb4-56c0-91f2-9895c78f1cf9)

He left before she woke the next morning. Rachel was glad, fixed herself coffee and opened her emails. Her inbox was filled with messages of congratulation. They’d made a mint on some of the more expensive works last night and several write-ups had already appeared in the morning’s coverage, calling the Square Peg launch ‘a triumph’ and ‘an enthralling odyssey into the city’s burning talent’. Paul had written with news that tickets for next month’s exhibition had sold out, and that a renowned London artist wished to make an appearance at the weekend. Rachel summoned Paul for brunch and closed her tablet.

It took minutes to get ready. Despite her lack of sleep, the bathroom mirror told her she looked good. With neat brown hair, warm hazel eyes and a smattering of freckles across her nose, Rachel was no supermodel, but she had a fine figure, great skin and she carried herself well. For a long time she had puzzled over the roots of her appearance. Most people didn’t have to – their parents were right in front of them, or they had pictures to go on, blood relatives to join the dots – and she had thought so many times about what a phenomenon that would be. Imagining her mother and father was a bit like imagining her own hypothetical child, as much of a mystery and a miracle. For she had no positioning in the world, no biological foundation: she wasn’t the branch or the leaf on a tree, running deep into the earth, permanent and enduring; she was her own shrub, small and lonely, with roots barely clinging to the soil.

Rachel had got along fine with her adoptive parents, Maggie and Greg. They had longed for a baby and been unable to have one of their own, and when they’d welcomed her at a week old, it had been the answer to their prayers. She was lucky, she knew: they’d been loving, supportive, attentive, and truthful with her, explaining her adoption as soon as she was old enough to understand. But, really, one was never old enough to understand something like that, to properly get to grips with and accept deep inside without umbrage or bitterness that you weren’t loved enough to be kept in the first place. ‘We chose you,’ Maggie used to say over and over, ‘because you were special. We adored you from the second we laid eyes on you.’ And Rachel used to take reassurance from this – that she might have been cast aside by one set of parents but at least she’d been picked up by another – until her older, more complicated years, when she had learned about the adoption process and that Maggie and Greg hadn’t selected her, she had simply been the first baby to come along. It was hard to get a baby, most childless couples wished for babies and there weren’t enough to go round, so no wonder her adoptive parents had felt she was meant to be.

Rachel knew this was ungrateful and unhelpful, so she’d stifled the truth of her emotions and instead focused on the future, always the next thing, getting ahead, refusing to look behind. When she’d referenced her mother in the gallery speech, she’d been remembering how Maggie used to describe her as ‘bloody-minded’. It was meant, for the most part, affectionately, but in her teenage years it had caused toxic fights. Rachel’s stubbornness, her iron will, whether it concerned dating a boy or staying out or refusing to finish her studies, came from a place that neither Maggie nor Greg could trace in themselves, a place so remote and unknown that it served only to remind them what was missing. That Rachel had a family out there who were just like her, and it was their blood that was running through her veins, not the Wrights’.

Maggie and Greg had died within a year of each other when she was eighteen, so she hadn’t had all that much of them either. At the time she’d mourned, but she never shed as many tears over them as she had over her imagined, other parents. It had seemed thankless and hurtful to pursue her heritage while Maggie and Greg were alive, but after they went there was nothing stopping her. Rachel knew she’d been born in England to English parents, and had ideas about travelling there, to some charming retreat or else a townhouse in London, and being welcomed by a woman smelling of vanilla sponge, a friendly wirehaired dog trailing at her feet. However, her ideas came to nothing and her search was short-lived: Rachel discovered inside a week that her birth mother was dead and she had no father listed. That was when she’d decided to close the door on the past. She spoke to no one about it. Nobody knew she was adopted and she preferred it that way. Keeping a lid on her feelings was a trick she’d learned early on, and it had certainly protected her since.

The sound of the mail hitting the mat pulled her from her thoughts. She grabbed her jacket and bent to scoop up the letters to look at later, but a single white envelope drew her up short. It was one of those envelopes that made you look twice. There was nothing menacing about it, nothing especially unusual but for the UK postal address and a red stamp reading STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL.

She picked it up and turned it over. Private documents enclosed. There was a return address, a Quakers Oatley & Sons Solicitors in Mayfair, London.

She ran her nail along the seal and opened it.

Chapter 5 (#ulink_84490ef5-cc58-5078-bad2-19e85ab31bd6)

Cornwall, 1947

Only when the captain moves to shake my hand does his face return to the light. It is a fine, distinguished face: the product of centuries of ancestral perfection. His eyes are blue and clear, startlingly bright in comparison with the rest of him. His hair is black and has grown out of its cut, longer and more dishevelled than is the fashion for gentlemen, and there is a faint shadow of, or prelude to, a beard, although that could be the gloom hitting him from beneath. The chin is striking, square and sharp, and his mouth is wide, the lips parted slightly, with a curl that could be mistaken for a sneer. It isn’t a kind mouth.

I notice all this before I notice the most obvious thing: his scars. I was warned about the captain’s war wounds, but I hadn’t known about his burns. His left cheek is pitted like fruit peel, the skin pulled tight towards the angle where his jaw meets his earlobe, where it melts into spilled candle wax.

His clear, blue eyes, as they meet mine, dare me to comment. For a shameful moment I am glad of his disfiguration, for if he were flawless I might not know how to speak. There is a scent about him, of tobacco and scorched wood.

‘Thank you, Tom,’ he says, ‘but I will show Miss Miller to her room.’

‘Very well, Captain.’

The mouth lifts then, but it isn’t quite a smile. Nonetheless I return it and follow him up to the landing. We make slow, awkward progress, and I see how much discomfort his leg causes him but also the pride that prevents him from admitting it.

‘Tell me,’ he starts, ‘what are your first impressions of Winterbourne?’

‘Well, I’ve only just arrived.’ We pass a glass case filled with stuffed birds: a hawk alights on a branch, wings wide, beak screaming. ‘But I should say what strikes me is that it’s very beautiful.’

‘Beautiful.’ The captain repeats the word, as if it’s foreign. ‘Winterbourne has been described as many things, but beautiful isn’t one of them.’

‘No? I’m surprised.’

‘It was built by a band of lunatics. Hardly the way to speak of one’s ancestors, but there’s the long and short of it. Too much money and too little discrimination. They thought they were recreating Notre-Dame, I’m sure. That families should be expected to live here, generations of us, hardly came into it. No – I’ve heard daunting, intimidating, bleak, desolate… but I’ve never heard beautiful.’

‘You don’t like your home, Captain?’

He gives a short, hollow laugh. ‘It isn’t a question of me not liking it. Rather the other way round.’

I frown, but before I can speak he stops at a door and draws a chain of keys from his pocket. It is necessary for him to lean against the wall to do this, wheezing slightly, and my instinct is to help him but I don’t. We are at the end of a passage. Looking back, the way we’ve come appears impossibly long, distortedly so, a carpeted corridor flickering in the glow of feeble bulbs. Ahead is a narrow staircase, presumably the servants’ access.

‘This is your room,’ he says, and the door creaks open.

The first thing I notice is the smell of age, a musty scent that seems to rise from the floorboards and seep from the walls. The atmosphere is deep, as weighty as the green velvet drapes that hang from the high window. There is a wooden four-poster bed, carved ornately in the Jacobean style, its quilts piled extravagantly. Chenille rugs adorn the boards beneath my feet, and behind me, on the wall we have stepped through, is an elaborate scenic mural depicting some dark, tangled foliage. Its pattern is dizzyingly complicated, impossible to follow one twisted vine without getting lost in the knots of the others.

‘Will this be adequate for you?’ says Jonathan de Grey. I nod. Of course it will be. It is, presumably, where his previous governess slept. She flits into my mind then vanishes just as quickly. I wonder about her sleeping here, watching the forest mural from her bed, trying to follow those creepers then unable to find her way out.

‘It’s lovely,’ I say. It isn’t true, just as perhaps ‘beautiful’ wasn’t quite true for Winterbourne. Just something people say to make things well. ‘I shall be very comfortable here.’ I go to the window, pull the curtains and flood the room with light. Already, it looks better. There is a little writing desk, a handsome wardrobe and an adjacent washing and dressing room. I think of my miserable lodgings in London and am once again amazed at the fortune that brought me here. All will be well.

‘I’ll leave you now,’ says the captain, stepping back. For a moment the daylight catches his features, the taut, pockmarked side of his face, and he shies from it like a creature of the night. ‘Mrs Yarrow will collect you shortly.’

The door closes and I am alone. Gradually the captain’s footsteps cease, and against the silence my ears tune into quieter sounds: sounds sewn into the building. I hear a soft tapping, most likely the flick of a branch at the window, but when I look out the wild trees are distant. I travel from one surface to another, the foot of the bed, the top of the wardrobe; I smile, as if the tapping is playing with me, a silly parlour game. It sounds louder at the desk so I open the drawer. Abruptly, the tapping stops – it was a draught behind the wall, or a mouse scratching at wood. Inside is a clock, small and round, 1920s, silver. The time reads twenty-five minutes to three, but the second hand isn’t working. There is an engraving on the back:

L. Until the end of time.

I remove the clock and put it on the table. I’ll see later if it can’t be fixed.

From the window, the view is tremendous. I must be on the westernmost gable because the sea appears huge and immediate, with no cliffs to separate us, as if it is washing right up to Winterbourne’s walls; or we could be on the Polcreath tower light, rising straight up out of the ocean, its root chalky with salt and seaweed. The water is dark, perfectly still closer to shore but in the distance little white crests jump and retreat on its surface. The sky is frozen white and copper, like a Turner painting, dashed with smears of dirty raincloud. I met a former lighthouse keeper, once, during the war. His house had been blown to dust in a bad Blitz. As I held his hand and waited for the ambulance to arrive, he told me of his time, years before, on a remote Atlantic outpost, and that he could never be afraid of the sea, no matter how it churned or roared. ‘The sea’s my friend,’ he assured me, his face blackened with ash. ‘If I fell into it, it would toss me back up. The sea would never take me.’ He missed the water like a lost love, he said; even through the noise and fury of war it called to him, calling him back to its lonely perfection. ‘It’s all right,’ he’d kept saying, as I told him he would find safety and a way to rebuild his life, ‘this wasn’t my life anyway. My life is out on the water,’ and he’d wept for a loss he could not express.

I consider if this sea will become my friend, looking at it every day, and it looking at me. So different from the rush and noise of London, which, once peace was declared, people told me would be a welcome diversion. Everyone was grieving, everyone was spent; everyone had known terrible things and faced terrible truths. But the city pumped on like an unstoppable heart, whisking us up with it, forcing us to go on even if some days we felt like lying down in the middle of the street and closing our eyes and never waking again. Carry on, carry on, that was the message throughout the war. What about after it ended? Carry on, they said, carry on. It was hard for me to carry on. There are some things from which you cannot carry on. Some things hurt too much. Things we did. Things we let happen. I close my eyes, unwilling to remember. A grasping hand, swirling hair, and her eyes, her eyes…

I am about to go and find Mrs Yarrow, whom I assume to be the cook, when something catches my eye that I didn’t notice before.

It is a painting, hanging in the shadow of the dark green curtain and no bigger than a place mat on a dining table. The frame, too, is large, so that the print inside is really quite small and delicate, and I have to lean in to see what it portrays.

It’s a little farm scene, a barn surrounded by hay bales and a grey band of sea just visible in the distance. A cow chews on a tuft of grass. Milking pails lie abandoned. A cluster of dark firs borders a simple cottage, its chimney smoking and a full moon hovering over its roof. The landscape is curiously recognisable as that around Winterbourne: we are here, in this place, at some distant, irretrievable point in the past. The moors are unmistakable, their wild desolation, the colour of the earth.

Perhaps it’s instinctive to look for a human face in these things, because I do, but even though I am looking it still comes as a surprise to me when I see her. She is merely a detail, an impression, not really a person; it’s more the feeling of her, looking out at the window, looking right back at me. Her head must be the size of a farthing, if that, with a wisp of dark hair and two green eyes. The artist has made a point of her eyes, the brightest colour in the picture. I think of the girl peering out at me, just as, a moment before, I was peering out at the sea from my own window. I think of us peering at each other, and for an instant the effect is unsettling, because it really appears that she is seeing me, and I her. Not really a person. Not really.

‘Miss Miller?’ There is a knock at the door.

I tie the curtain back, obscuring the print, and go to answer it.

*

I don’t realise I am hungry until Mrs Yarrow puts soup and a sandwich in front of me, a doorstop of cheese and ham. I remember sharing my butter ration with Mrs Wilson at Quakers Oatley after her husband died, and what another world London seems.

Mrs Yarrow fusses about me like a mother, fetching milk, then a pudding of lemon meringue pie with gingerbread biscuits. I haven’t eaten so much in months.

‘Well, I’ve had practice,’ she says, when I compliment her on her cooking. ‘I’ve worked here for the captain for twenty years, and practice makes perfect, as they say.’ She has a West Country burr, is plump and pink-cheeked, and her frizzy brown hair escapes in soft tendrils from her cap. She sits opposite me, her hands in her lap.

‘Are we pleased to have you joining us, miss,’ she says, with such visible relief that it seems almost inappropriate.

‘I’m pleased to be here.’

‘I don’t know how much longer the captain could have coped. Things have been…testing.’

‘Since my predecessor left?’

Mrs Yarrow nods. ‘I’ve been in charge of the children. As you can imagine, I have my hands full enough with the daily running of things. It was really too much. But none of us wants to let the captain down.’

‘Of course not.’

‘It will be good for the children to have proper care.’ Mrs Yarrow shifts in her seat; she has the manner of somebody loose-tongued trying not to tell a secret. ‘All this up and down, here and gone, no consistency, miss, that’s the problem.’

‘It must have been confusing for them.’ I sip my tea.

‘Yes. Confusing. That’s it.’

‘And to have lost their poor mother, as well.’

‘Oh, yes, miss. That were quite a thing.’

I want to ask again after Mrs de Grey; I want her to tell me. But Mrs Yarrow has reddened and her eyes have fallen to her lap. She looks afraid.

‘I must say I feel fond of the twins already,’ I say instead. ‘To be so young and to go through so much.’

‘Ah, but the young are strong,’ says Mrs Yarrow. ‘Stronger than I, in any case. You’ll see what I mean when you meet them.’

She sees me gazing up at the kitchen shelves, at the soup tureens and jelly moulds coated in dust, at the giant mixing bowls and tarnished ladles, at the china plates and casseroles and long-unused tea sets with their chipped edges and mismatched saucers. The space is cavernous, great wooden worktops and a central island around which we sit, but it’s draughty now in the early evening and its size only summons the buzz and activity that’s missing. Once, this would have been the hub of the house. Today, it’s a graveyard: a ghost of times gone by. I wonder if Mrs de Grey cooked here, her hands dusted with flour and her babies crawling round her skirts. Or perhaps she cut a remote figure, closeted away with her thoughts, wringing her fingers, which I picture as studded with jewels. I know how treacherous thoughts can be. That if you are left alone with them for too long, they can turn against you.

‘It was strange how the war brought Winterbourne back to us,’ says Mrs Yarrow, brightening. ‘When we had the children here – the evacuees – it was like old times. Voices everywhere, running feet, excitement. You wouldn’t have recognised this place.’ She gestures about her. ‘We had littluns piled all round this table, sticking their fingers into cake mix, playing hide and seek in the tower, getting up to mischief with the bell box. Bells were ringing all through the house, miss, and we soon found out why! That was just after the twins came along. Madam used to complain that she couldn’t get any sleep because of the noise. She’d go upstairs to lie down in the day, while I took the babes, and she couldn’t rest for all the shrieking. But, now they’ve gone, it does seem quiet, doesn’t it?’ Mrs Yarrow shakes her head, as if at a fond memory. ‘I still think I hear them sometimes, isn’t that a funny thing? It’s a trick of Winterbourne, lots of creaks and knocks where the wind gets in. And the twins, of course, they can cause a racket – they can make enough noise for twenty children. You’ll have your hands full with them, miss.’

‘By all accounts they’re well behaved.’

‘Oh, absolutely,’ agrees Mrs Yarrow, wholeheartedly, as if in swift correction of having spoken out of turn. She slips a finger beneath the elastic of her cap and scratches her head.‘I mean only that they’re tiring for a woman my age. Do you have children, miss?’ The question is so abrupt and unexpected that I glance away.

‘No.’

‘I’m sorry. I don’t mean to pry. I didn’t suppose you would, in accepting this station.’

‘You’re right. One day, perhaps.’ I force a smile. It takes an enormous effort of will, but I must manage it because she returns it easily, our awkwardness forgotten.

‘Well,’ I say, changing the subject, ‘I expect you’ll be a veritable mine of information and knowledge for me over the coming days.’

Mrs Yarrow nods. ‘Of course, I’d be delighted. Although,’ she lowers her voice, ‘between you and me, I confess I’m thinking about moving on.’

‘You are?’

‘It’s early days. But I’m getting too long in the tooth for this, miss. Since the last girl left…’ She swallows, an audible, dry contraction. Is it my imagination, or has the cook turned pale, her skin appearing waxen in the fading light, her brow heavy and her eyes deep with some unfathomable terror? ‘It hasn’t been easy. Looking after the children hasn’t been easy. It’s better if I have a fresh start, somewhere new. The captain won’t like it, but he’ll have you. You’ll be the woman of this house next, miss. And you’ll like it. Winterbourne is a special place, a very special place.’

At once, there is clamour from the staircase, a storm of battering, hurrying footsteps like the ack-ack gunfire of home, and Mrs Yarrow forgets her worried turn, straightens and smiles, smoothing her apron as if about to curtsey to the king.

‘Speak of the devils,’ she says, ‘here they come now. Would you like to come and meet them, miss? Edmund and Constance de Grey. They’ve been so looking forward to this.’

Chapter 6 (#ulink_928532cd-daab-57ce-bbc2-d9c2eed1cc14)

The twins run straight into me, their arms around my waist. It almost knocks me over. I laugh, as if being greeted by dogs, friendly, tails wagging, craving attention.

‘Miss Miller, Miss Miller, what a delight!’ The girl looks up at me, impossibly pretty, her grin wide to expose a row of little teeth, as neat as a bracelet. A velvet clip holds her blonde ringlets back and her blue eyes are shining. She has the face of a doll, precise and sweet, with a dimple in her chin that you struggle not to press with your thumb. She is the loveliest thing I have ever seen.

‘Oh, call me Alice!’ I say.

‘May we play with her, Father?’ the boy says, and only then do I realise that the captain is present, his cane in hand. It must be an effort for him to stand because he lowers himself into a chair by the fire. ‘May we please?’

‘Be gentle, Edmund,’ he answers.

Looking at Edmund, it is impossible to imagine the boy being anything but. For all their twinship, the children do not look alike. Edmund has been blessed with copper curls, a crop of them that shine like burnished gold. Across his nose is a light dusting of freckles, and his skin is porcelain-pale and smooth as cream.

They are a pair of angels. Constance tugs my hand and I crouch so I can look up at them both. I have never seen two such innocent faces, shining with happiness and every good thing. ‘I have something for you,’ Constance whispers. Edmund nudges her: ‘Give it to her, silly!’ Constance fishes in the pocket of her dress.

It’s a chain, woven out of grass. The thought is so pure and touching that for a moment I don’t know what to say. Nobody told me how enchanting these children were, not my contact in London, not Tom, not Mrs Yarrow, not even Jonathan de Grey. But enchanting they are, smiling down at me, awaiting my response.

‘How clever of you,’ I say, admiring the grass. ‘And how kind.’

‘Put it on, put it on!’ Constance helps me.

In a flash I am reminded of another time, another bracelet, somebody else helping me to fasten the clasp. That bracelet was gold, and if I concentrate hard I can feel his thumbs on that part of my wrist, over my pulse, his skin warm against mine…

‘There!’ cries Constance triumphantly.

‘Well,’ I say, ‘doesn’t that look splendid.’

‘Capital!’ agrees Edmund.

‘Miss Miller is going to be tired,’ says their father. I glance at him, and for an odd, unaccountable moment the four of us seem absolutely right, together in this dim hall, with Mrs Yarrow hanging dutifully back, as if we are the family, and I am the wife, and I am the mother… The impression vanishes as soon as it appears.

‘She says we can call her Alice!’ says Constance, tugging at my hand once more, her fingers looped through mine. It’s infectious, I’ll admit, and I laugh. It sounds unfamiliar in my throat, girlish, as if it’s a younger me making the sound.

‘Very well,’ says the captain. ‘Alice,’ he pauses, tasting my name: I see him taste it, ‘will be tired. You’re to let her rest this evening. Tomorrow is another day.’

‘But we can’t sleep,’ objects Edmund. ‘We want to play with her – please, Father? Please may we play with her, please?’

The captain stands, his cane striking the floor in a deafening blow. Mrs Yarrow gasps. I get to my feet. The children drop my hands.

‘Do I need to repeat myself?’ the captain says.

Edmund shakes his head.

‘Did you hear me the first time, boy?’

The child nods.

‘Then I neither expect nor welcome your protest. You are to follow my instructions to the letter, do you understand? And, from tonight, you are to follow Miss Miller’s.’ He turns to me. ‘Miss Miller, if you would…?’ I try not to feel afraid, for the growl of his voice and the thunder of his cane casts a shadow across the house.

‘Up to bed, children,’ I say softly. ‘Cook will bring you some cocoa.’

The children retreat, sloping upstairs like kittens in the rain. It troubles me to see the spirit pinched out of them. It troubles me how fast the captain’s temper caught light. Now he bids us goodnight and slips away to another part of the house.

‘The captain prefers the children to be seen and not heard,’ says Mrs Yarrow.

‘Yes,’ I say. ‘I rather got that impression.’

*

Morning arrives with a burst of sunshine. I wake in my four-poster bed, shrugging off a deep, dreamless sleep, the likes of which I haven’t had since before the war, and go straight to the window to welcome the day. Despite the thick drapes, sunlight razes through the cracks like an outline of fire. I pull them open and let it in. The sea is green today, light, sparkling green, and the sky above a hazy blue. I prise open the window, a hook on a rusted latch, and a draught of fresh, salty air hits my nostrils. I feel like a girl on Christmas morning. I cannot wait to see the twins once more.

When I tie back the curtains, I spy that painting again – the little girl looking out of the cottage. She has one hand flat against the panes, a detail I hadn’t noticed yesterday. The hand is raised as if in greeting or acknowledgement. Or warning.

A bell sounds downstairs. It makes me jump. I feel as I did at Burstead, late for breakfast, the house matrons stalking the corridors with their starched bosoms and shrill whistles. ‘Come on, Miller! Get dressed, Miller! What are you doing, girl?’

In minutes I’m downstairs – but the bell wasn’t for me, of course, it was for the children. Mrs Yarrow has bowls of porridge steaming on the table, decorated with honey and walnuts. ‘Did you sleep well, miss?’ she asks me.

‘Very well, thank you.’

‘You didn’t hear the dogs?’

‘What dogs?’

‘We’ve got a wandering madcap,’ she rattles cutlery out of a drawer, ‘Marlin, they call him. Well, he’s got these giant hounds and walks them on the cliffs at night.’ She lays the spoons on the table. ‘God knows why, miss. And they make the most terrible noise, howling and yowling and yelping at the moon. It used to keep Madam awake something rotten. The children, too, when they were babes. Luckily he doesn’t come as close to Winterbourne as he used to, since the captain and he had words. But do you know what this man Marlin said to the captain? He said: It’s your house that makes my dogs afraid. It’s your house that’s the trouble. So the captain says not to bother walking them round here again, if that’s the way he feels. But still he does.’

‘Is he a local man?’

‘Lived here for years. Not the most sociable person you’ll meet.’

‘I do like dogs. What breed are they?’

The cook goes to the bell a second time, rings it. ‘You won’t like these ones, miss. These aren’t right. They’re great snarling things with huge teeth, and paws that could fell a man in a stroke. To think of them being scared by a big old house is a nonsense. The captain chooses not to let it vex him, but I hate to hear them at night.’

‘I didn’t hear them.’

She turns her back. ‘You must have slept soundly.’

We are interrupted by the children’s arrival, a tornado of gold and copper and neatly pressed shirts and shorts, a frill of dress, twinkling eyes and gracious smiles. ‘Miss Miller! Alice! See, I said we didn’t dream her!’ In the glow of the kitchen, Constance and Edmund appear even more adorable than they did last evening.

Constance takes my hand, her small, perfect fingers looping through mine.

‘Father said we’re not to touch her,’ says Edmund. ‘Remember?’

‘Alice doesn’t mind,’ says Constance, ‘do you, Alice?’

‘I won’t break.’

‘Constance breaks all her toys,’ says Edmund. ‘That’s why I won’t let her play with any of mine. Especially my locomotives.’

‘I do not!’ objects the girl.

‘Chop-chop, children,’ says Mrs Yarrow, encouraging them to sit. ‘Miss Miller will want to get on with your lessons this morning. Eat your breakfast first.’

‘I can eat one-handed,’ says Constance. ‘I’m not letting go.’

I ought to deter her, follow the captain’s rules. But there is such charm about her, about them both, that I am happy to be held.

I’m not letting go.

I was told that before, in another life, when I was another girl. It’s not an easy thing to hear, neither is it easy to resist. And I was let go, wasn’t I? Our hands parted, and I fell.

*

Thus far the children have been educated in an upstairs bedroom, one of the many chambers at Winterbourne that otherwise go unused. On seeing the forlorn space, a dark turret with the oppressive atmosphere of a sanatorium, I immediately decide to relocate. ‘Oh, I never liked it,’ agrees Mrs Yarrow, as she helps Tom and me carry the desks to the drawing room. As the stand-in between governesses, she’d been employed short-term in the twins’ tutelage. ‘Too dingy, and the children kept complaining of coughs and chills. Besides, I could feel her watching me all the time.’

‘Her?’

‘The woman who was here before you,’ Mrs Yarrow says quickly, under Tom’s dissatisfied glare. ‘She had her ways of doing things. That’s all.’

‘What sort of ways?’

‘Oh, nothing, nothing important…’

‘Is this very well for you, miss?’ Tom squares the desks so they’re facing the window. ‘Will you need anything else?’

‘Thank you, Tom, that will be all. Children should be educated in a good light, don’t you agree, Mrs Yarrow? I want Edmund and Constance to feel inspired by our lessons, and where better place to start than with a fine view of nature.’

‘Right you are.’

And I must admit, an hour later, I am feeling positive about our progress. The de Grey twins continue to amaze me in their enthusiasm, their confidence, and their understanding that whatever they know is a mere grain when set against what still remains to be found. They are unfailingly polite, amenable characters with a zest for learning, making my job no less than a pleasure. I had worried, slightly, for the educative aspect. I had been honest about my lack of teaching experience but feared it would prove a challenge. Now I see why my honesty didn’t count against me: these pupils are just about the easiest, loveliest, most rewarding novices a teacher could hope to influence. Whatever methods my predecessor had, they must have worked.

After lunch, the three of us venture into parkland. The lawns at Winterbourne would once have been impeccably tended, but now, as I observed in the Rolls when we first approached, they are hopelessly overgrown. Creepers straggle across the paths; chipped stone planters are covered in moss, and two lion heads at the top of a run of steps have ears and eyes missing, stolen by the elements. The topiary is melted out of shape and the whole impression is one of a garden underwater, liquid and strange. Behind us, Winterbourne rises in giant, eerie magnificence. I hear the sea, an incessant, rhythmic breath as it washes into shore.

‘This afternoon,’ I tell them as we take the path to the wood, ‘we’re going to draw a picture.’ I’m invigorated by the day: the sun, the sky and the birdsong.

‘Like a flower?’ says Constance.

‘Like a fox,’ says Edmund.

‘A flower would be easier to draw than a fox,’ I say, ‘because we need to be able to really look at it. We’re going to look at it in incredible detail, and keep looking at it as we draw, so that we can reproduce as accurate a likeness as possible.’

‘It has to be still, then,’ says Edmund.

‘That’s absolutely right. One can draw a moving thing, of course one can, but one isn’t able to study it with as much care.’ We pick our way over a twisted tree branch. The children are used to coming this way for they step over it easily, while I am obliged to stop and adjust my skirt. ‘Tom found a dead fox,’ says Edmund. He collects a stick and pokes the ground with it. ‘He’s always finding dead foxes.’

‘Edmund!’ Constance covers her ears.

‘It’s all right, Constance.’ I smile. ‘Nature is red in tooth and claw.’

‘I don’t like it.’

‘Could I draw a dead fox?’ says Edmund.

‘You could if you wanted. But it’s rather morbid, don’t you think?’

‘But I could study it, in detail, then, as you say. It wouldn’t be able to get away from me. It wouldn’t be able to run away.’

‘True. But when you looked at your picture afterwards, you wouldn’t think of the fox as living, would you? You wouldn’t remember how clever you were to reproduce its detail as it rushed through the wood. You’d remember it as a body.’

‘And you’d hate to look at it,’ says Constance. ‘It would make you sad.’

‘I suppose,’ says Edmund. A neat frown puckers his childish brow. ‘But Father has his case of birds – those stuffed crows on the landing. They used to scare us, didn’t they, Connie? We’d run past them with our eyes shut in case they jumped out and pecked us! People like to look at those, and that’s the same thing, isn’t it?’

I spy a place for us to sketch, a soft clearing, surrounded by flora.

‘It depends on the person,’ I say. ‘Everybody likes different things. Hence the multiplicity of art.’

‘What does multiplicity mean?’

‘A big collection, full of variety.’

‘I’m going to draw a flower,’ says Constance.

‘That’s boring,’ says the boy.

‘In your opinion,’ I tell him. ‘And that’s what we’re talking about. Art is preference. Art is personal. Constance prefers the flower, while you prefer the fox. Neither is right or wrong. It’s about what you wish to see in the thing you’re looking at. Do you wish to observe a living soul, or do you wish to capture it?’

Edmund thinks about it for a moment. Then he smiles cunningly and says,‘May we draw you, miss?’

‘That isn’t really the object of the exercise.’

‘Alice is a pretty name,’ interjects Constance.

‘Thank you.’

‘I wish I were called Alice.’

‘Constance is lovely. It means for ever.’

‘That’s what Mummy used to say.’

The mention of their mother catches me off guard. Another detail, another candle held up to the frozen mist I hold in my mind. What did Mrs de Grey look like? Was she fair, like me, or dark like her husband? She must have been very beautiful, I think, to have such beautiful children and to have attracted a man like the captain.

It is a relief to reach the clearing, and to incite the children to sit and open their sketchbooks. Perhaps it is the ghost of Mrs de Grey still clinging to our collective mood, or perhaps it is the sheer sweetness of their faces as they gaze hopefully up at me, but before I know it I have agreed to Edmund’s request and am sitting opposite on a blanket, preparing to be drawn. ‘Wait—!’ calls Constance, and she jumps up and brings a daisy to me, which she threads through my hair.

‘There,’ she says, kissing my cheek. ‘Now it’s perfect.’

‘Be kind to me, won’t you?’ I say.

‘We’re always kind,’ says Edmund.

Chapter 7 (#ulink_afb254ad-5073-5419-a6d1-309890b58b10)

New York, present day

Quakers Oatley Solicitors

St James House

Richmond Square

Mayfair

London W1—

Ms Rachel Wright

Apt 243E

West 27

Street, NY—

9 September 2016

Dear Ms Wright

Re: Winterbourne Hall, Polcreath, Cornwall

It is with regret that I write to inform you of the death of your aunt Constance de Grey, who passed away at her ancestral home in the early hours of Sunday morning.

I am conscious that this might come as something of a surprise, as I believe you were unaware of your connection with the Winterbourne Estate. Nonetheless, as the de Grey family solicitor, it is my duty to inform you that, being Miss de Grey’s next of kin, the park and all its land and contents now fall directly into your possession.

I would appreciate a swift response indicating how you would like to proceed. Under these circumstances, I normally advise a visit to our offices in London, where we can make the necessary inroads before granting you access to your inheritance.

Yours faithfully

Stephen Oatley, Esq.

Chapter 8 (#ulink_10fb663b-b6ec-5d66-8266-4ebdead54617)

Rachel read the letter, then read it again. Her first thought was that it was a joke. She even looked about her, expecting a camera to be on her, or a crowd to appear, ready to laugh along. But her apartment was unchanged. Outside, the traffic droned on.

Her hands were shaking. Quickly she replaced the letter in its envelope, sitting down because her knees had turned to jelly. The envelope, that anodyne thing, seemed to pulse on the kitchen table. She folded it back out, looked again. Impossible. It was totally impossible. She searched for a clue to its falsehood; her mind tripped over a dozen hoaxes but none fitted with such an outrageous set of claims as this. And yet a voice whispered, It’s plausible, it might be, louder and more insistent each time.

Her phone rang. It was Paul. ‘Hey,’ he said, ‘guess what? The City wants to interview you, tomorrow at ten; I’ve booked you a spot at Jacob’s. Sound good?’

She was slow to reply, unlike her. ‘I don’t know, I…’

He was surprised at her reticence. ‘I can put them back, if you like?’

‘Listen, Paul,’ she said, making a decision, ‘I think you’ll have to. In fact, you can clear my schedule for the rest of the week. Next week, too.’