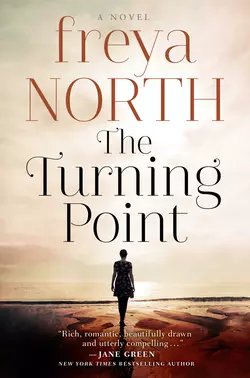

The Turning Point: A gripping love story, keep the tissues close...

Freya North

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 292.56 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 25.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: “If you cried at Jojo Moyes’ Me Before You, get your hankies ready.” –Booklist (starred review)“Rich, romantic, beautifully drawn and utterly compelling” Jane Green, New York Times bestselling authorA poignant read with a heartbreaking twist for all fans of Me Before You.Two single parents, Frankie and Scott, meet unexpectedly. Their homes are far apart: Frankie lives with her children on the North Norfolk coast, Scott in the mountains of British Columbia. Yet though thousands of miles divide them, a million little things connect them. A spark ignites, a recognition so strong that it dares them to take a risk.For two families, life is about to change. But no-one could have anticipated how…