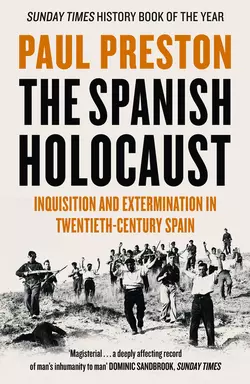

The Spanish Holocaust: Inquisition and Extermination in Twentieth-Century Spain

Paul Preston

In this Samuel Johnson Prize short-listed work of meticulous scholarship, Paul Preston, the world’s foremost historian of 20th-century Spain, charts how and why Franco and his supporters set out to eliminate all ‘those who do not think as we do’ – some 200,000 innocent men, women and children across Spain.The remains of General Franco lie in an immense mausoleum near Madrid, built with the blood and sweat of 20,000 slave labourers. His enemies, however, met less exalted fates. In addition to those killed on the battlefield, tens of thousands of Spaniards were officially executed between 1936 and 1945, and as many again became ‘non-persons’, their fates as obscure as the nation’s collective memory of this terrible period.As the country slowly reclaims its historical memory after a long period of wilful amnesia, for the first time a full picture can be given of the escalation and aftermath of the Spanish Holocaust in all its dimensions – ranging from systematic killings and judicial murders to the abuse of women and children, imprisonment, torture and the grisly fate of Spaniards in the hands of the Gestapo.The story of the victims of Franco’s reign of terror is framed by the activities of four key men whose dogma of eugenics, terrorisation, domination and mind control horrifyingly mirror the fascism of 1930s Italy and Germany. General Mola organised the military coup of 1936 and dictated its ferocity in the north of Spain; Queipo de Llano, the deranged ‘radio general’, ran a virtually independent fiefdom in the south; Major Vallejo Najera was a military psychiatrist who provided ‘scientific’ justifications for the annihilation of thousands; and Captain Aguilera, the Nationalist press officer, blamed the war on do-gooders’ interference with the divine process of decimating the working classes.Reflecting more than a decade of research, and telling many stories of individuals from both sides, The Spanish Holocaust seeks to reflect the intense horrors visited upon Spain by the arrogance and brutality of the officers who rose up on 17 July 1936, provoking a civil war that was unnecessary and whose consequences still reverberate bitterly in Spain today.

The Spanish Holocaust

Inquisition and Extermination in Twentieth-Century Spain

Paul Preston

Copyright

HarperPress

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Published in Great Britain by HarperPress in 2012

Copyright © Paul Preston 2012

Paul Preston asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

THE SPANISH HOLOCAUST. Copyright © Paul Preston 2012. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780002556347

Ebook Edition © JANUARY 2013 ISBN: 9780007467228

Version: 2016-07-04

Dedication

For Gabrielle

CONTENTS

Cover (#ulink_50486e22-1f87-5140-a963-2bba1bb21b86)

Title Page

Dedication

List of Illustrations

Prologue

PART 1: THE ORIGINS OF HATRED AND VIOLENCE

1 Social War Begins, 1931–1933

2 Theorists of Extermination

3 The Right Goes on the Offensive, 1933–1934

4 The Coming of War, 1934–1936

PART 2: INSTITUTIONALIZED VIOLENCE IN THE REBEL ZONE

5 Queipo’s Terror: The Purging of the South

6 Mola’s Terror: The Purging of Navarre, Galicia, Castile and León

PART 3: THE CONSEQUENCE OF THE COUP: SPONTANEOUS VIOLENCE IN THE REPUBLICAN ZONE

7 Far from the Front: Repression behind the Republican Lines

8 Revolutionary Terror in Madrid

PART 4: MADRID BESIEGED: THE THREAT AND THE RESPONSE

9 The Column of Death’s March on Madrid

10 A Terrified City Responds: The Massacres of Paracuellos

PART 5: TWO CONCEPTS OF WAR

11 Defending the Republic from the Enemy Within

12 Franco’s Slow War of Annihilation

PART 6: FRANCO’S INVESTMENT IN TERROR

13 No Reconciliation: Trials, Executions, Prisons

Epilogue: The Reverberations

Acknowledgements

Photographic Insert

Glossary

Notes

Appendix

Searchable Terms

Other Books by Paul Preston

Copyright

About the Publisher

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Franco in Seville with the brutal leader of the ‘Column of Death’, Colonel Juan Yagüe. (© ICAS-SAHP, Fototeca Municipal de Sevilla, Fondo Serrano)

Yagüe’s artillery chief, Luis Alarcón de la Lastra. (EFE/jt)

General Gonzalo Queipo de Llano. (EFE/Jalon Angel)

General Emilio Mola. (EFE/Delespro/jt)

Gonzalo de Aguilera. (Courtesy of Marianela de la Trinidad de Aguilera y Lodeiro, Condesa de Alba de Yeltes)

Virgilio Leret with his wife, the feminist, Carlota O’Neill. (Courtesy of Carlota Leret-O’Neill)

Amparo Barayón. (Courtesy of Ramon Sender Barayón)

A Coruña, Anniversary of the foundation of the Second Republic, 14 April 1936. (Fondo Suárez Ferrín, Proxecto “Nomes e Voces”, Santiago de Compostela)

José González Barrero, Mayor of Zafra. (Courtesy of González Barrero family)

Modesto José Lorenzana Macarro, Mayor of Fuente de Cantos. (Courtesy of Cayetano Ibarra)

Ricardo Zabalza, secretary general of the FNTT and Civil Governor of Valencia during the war, with his wife Obdulia Bermejo. (Courtesy of Abel Zabalza and Emilio Majuelo)

Mourning women after Castejón’s purge of the Triana district of Seville, 21 July 1936. (© ICAS-SAHP, Fototeca Municipal de Sevilla, Fondo Serrano)

Queipo de Llano (foreground) inspects the 5º Bandera of the Legion in Seville on 2 August 1936. (© ICAS-SAHP, Fototeca Municipal de Sevilla, Fondo Serrano)

Rafael de Medina Villalonga, in white, leads the column that has captured the town of Tocina, 4 August 1936. (© ICAS-SAHP, Fototeca Municipal de Sevilla, Fondo Serrano)

Trucks taking miners captured in the ambush at La Pañoleta for execution. (© ICAS-SAHP, Fototeca Municipal de Sevilla, Fondo Serrano)

Utrera, 26 July 1936. Townsfolk taken prisoner by the column of the Legion which captured the town. (© ICAS-SAHP, Fototeca Municipal de Sevilla, Fondo Serrano)

Lorca’s gravediggers. (Courtesy of Víctor Fernández and Colección Enrique Sabater)

Regulares examine their plunder. (© ICAS-SAHP, Fototeca Municipal de Sevilla, Fondo Serrano)

After a village falls, the column moves on with stolen sewing machines, household goods and animals. (© ICAS-SAHP, Fototeca Municipal de Sevilla, Fondo Serrano)

A firing squad prepares to execute townspeople in Llerena. (Archivo Histórico Municipal de Llerena, Fondo Pacheco Pereira, legajo 1.)

Calle Carnicerías (Butchery Street) in Talavera de la Reina. (© ICAS-SAHP, Fototeca Municipal de Sevilla, Fondo Serrano)

Mass grave near Toledo. (© ICAS-SAHP, Fototeca Municipal de Sevilla, Fondo Serrano)

Pascual Fresquet (centre left) with his ‘death brigade’ in Caspe. (España. Ministerio de Cultura. Centro Documental de la Memoria Histórica. FC-CAUSA_GENERAL, 1426, EXP.45, IMAGEN128)

The seizure of the Iglesia del Carmen in Madrid by militiamen. (España. Ministerio de Cultura. Centro Documental de la Memoria Histórica. FC-Causa_General, 1907, 1, p.81)

Arms and uniforms of the Falange found by militiamen in the offices of the monarchist newspaper ABC. (España. Ministerio de Cultura. Centro Documental de la Memoria Histórica. FC-Causa_General, 1814, 1, IMAGEN6)

Aurelio Fernández. (International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam, IISG-CNT)

Juan García Oliver. (International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam, IISG-CNT)

Ángel Pedrero García. (España. Ministerio de Cultura. Centro Documental de la Memoria Histórica. FC-CAUSA_GENERAL, 1547, EXP.9, IMAGEN45)

The Brigada García Atadell outside their Madrid headquarters, the Rincón Palace. (EFE/Díaz Casariego/jgb)

Santiago Carrillo. (EFE/jgb)

Melchor Rodríguez. (EFE/Vidal/jgb)

The wounded Pablo Yagüe receives visitors. (EFE/Vidal/jgb)

The cameraman Roman Karmen and the Pravda correspondent Mikhail Koltsov. (Courtesy of Victor Alexandrovich Frandkin, Koltsov family)

Andreu Nin and Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko. (L’Arxiu Fotogràfic de Barcelona)

Josif Grigulevich, the Brigadas Especiales, Roman Karmen, then two of the NKVD staff, Lev Vasilevsky and then his boss, Grigory Sergeievich Syroyezhkin. Madrid October 1936. (Cañada Blanch Collection)

Vittorio Vidali. (Imperial War Museum)

Refugees flee from Queipo’s repression in Málaga towards Almería. (Photograph by Hazen Sise, reproduced courtesy of Jesús Majada and El Centro Andaluz de la Fotografía)

Exhaustion overcomes the refugees from Málaga on the road to Almería. (Photograph by Hazen Sise, reproduced courtesy of Jesús Majada and El Centro Andaluz de la Fotografía)

The Regulares enter northern Catalonia January 1939. (España. Ministerio de Cultura. Centro Documental de la Memoria Histórica. FOTOGRAFIAS-DESCHAMPS, FOTO.7)

Republican prisoners packed into the fortress of Montjuich in Barcelona, February 1939. (España. Ministerio de Cultura. Centro Documental de la Memoria Histórica. FOTOGRAFIAS-DESCHAMPS, FOTO.764)

No military threat from those making the long trek to the French border. (Photos 12/Alamy)

A crowd of Spanish women and children refugees cross the border into France at Le Perthus. (Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS)

Recently arrived at Argelès, women await classification. (Roger-Viollet/Rex Features)

The male refugees are detained at Argelès – the only facility being barbed wire. (Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS)

Prisoners carry rocks up the staircase at the Mauthausen-Gusen death camp. (akg-images/ullstein bild)

Franco welcomes Himmler to Madrid. (EFE/Hermes Pato/jgb)

Antonio Vallejo-Nájera. (EFE/jgb)

Himmler visits the psycho-technic checa of Alfonso Laurencic in Barcelona. (L’Arxiu Fotogràfic de Barcelona)

Drawings made by Simon Manfield during the excavation at Valdedios, Asturias, summer 2003. (© Simon Manfield. Part of the Memoria Histórica series, simonmanfield@hotmail.com)

PROLOGUE

Behind the lines during the Spanish Civil War, nearly 200,000 men and women were murdered extra-judicially or executed after flimsy legal process. They were killed as a result of the military coup of 17–18 July 1936 against the Second Republic. For the same reason, perhaps as many as 200,000 men died at the battle fronts. Unknown numbers of men, women and children were killed in bombing attacks and in the exoduses that followed the occupation of territory by Franco’s military forces. In all of Spain after the final victory of the rebels at the end of March 1939, approximately 20,000 Republicans were executed. Many more died of disease and malnutrition in overcrowded, unhygienic prisons and concentration camps. Others died in the slave-labour conditions of work battalions. More than half a million refugees were forced into exile and many were to die of disease in French concentration camps. Several thousand were worked to death in Nazi camps. The purpose of this book is to show as far as possible what happened to civilians and why. All of what did happen constitutes what I believe can legitimately be called the Spanish holocaust.

I thought long and hard about using the word ‘holocaust’ in the title of this book. I feel intense sorrow and outrage about the Nazis’ deliberate attempt to annihilate European Jewry. I also feel intense sorrow and outrage about the lesser, but none the less massive, suffering undergone by the Spanish people during the Civil War of 1936–9 and for several years thereafter. I could find no word that more accurately encapsulates the Spanish experience than ‘holocaust’. Moreover, in choosing it, I was influenced by the fact that those who justified the slaughter of innocent Spaniards used an anti-Semitic rhetoric and frequently claimed that they had to be exterminated because they were the instruments of a ‘Jewish–Bolshevik–Masonic’ conspiracy. Nevertheless, my use of the word ‘holocaust’ is not intended to equate what happened within Spain with what happened throughout the rest of continental Europe under German occupation but rather to suggest that it be examined in a broadly comparative context. It is hoped thereby to suggest parallels and resonances that will lead to a better understanding of what happened in Spain during the Civil War and after.

To this day, General Franco and his regime enjoy a relatively good press. This derives from a series of persistent myths about the benefits of his rule. Along with the carefully constructed idea that he masterminded Spain’s economic ‘miracle’ in the 1960s and heroically kept his country out of the Second World War, there are numerous falsifications about the origins of his regime. These derive from the initial lie that the Spanish Civil War was a necessary war fought to save the country from Communist take-over. The success of this fabrication influenced much writing on the Spanish Civil War to depict it as a conflict between two more or less equal sides. The issue of innocent civilian casualties is subsumed into that concept and thereby ‘normalized’. Moreover, anti-communism, a reluctance to believe that officers and gentlemen could be involved in the deliberate mass slaughter of civilians and distaste for anti-clerical violence go some way to explaining a major lacuna in the historiography of the war.

The extent to which the rebels’ war effort was built on a prior plan of systematic mass murder and their subsequent regime on state terror is given relatively little weight in the literature on the Spanish conflict and its aftermath. The same may be said of the fact that a chain reaction which fuelled retaliatory mass assassinations within the loyalist zone was set off once the exterminatory plans of the military rebels began to be implemented from the night of 17 July 1936. The collective violence in both rearguards unleashed by brutal perpetrators against undeserving victims justifies the use of the word ‘holocaust’ in this context not just because of its extent but also because its resonances of systematic murder should be invoked in the Spanish case, as they are in those of Germany and Russia.

There were two rearguard repressions, one each in the Republican and rebel zones. Although very different, both quantitatively and qualitatively, each claimed tens of thousands of lives, most of them innocent of wrongdoing or even of political activism. The leaders of the rebellion, Generals Mola, Franco and Queipo de Llano, regarded the Spanish proletariat in the same way as they did the Moroccan, as an inferior race that had to be subjugated by sudden, uncompromising violence. Thus they applied in Spain the exemplary terror they had learned in North Africa by deploying the Spanish Foreign Legion and Moroccan mercenaries, the Regulares, of the colonial army.

Their approval of the grim violence of their men is reflected in Franco’s war diary of 1922, which lovingly describes Moroccan villages destroyed and their defenders decapitated. He delights in recounting how his teenage bugler boy cut off the ear of a captive.

Franco himself led twelve Legionarios on a raid from which they returned carrying as trophies the bloody heads of twelve tribesmen (harqueños).

The decapitation and mutilation of prisoners was common. When General Miguel Primo de Rivera visited Morocco in 1926, an entire battalion of the Legion awaited inspection with heads stuck on their bayonets.

During the Civil War, terror by the African Army was similarly deployed on the Spanish mainland as the instrument of a coldly conceived project to underpin a future authoritarian regime.

The repression carried out by the military rebels was a carefully planned operation to eliminate, in the words of the director of the coup, Emilio Mola, ‘without scruple or hesitation those who do not think as we do’.

In contrast, the repression in the Republican zone was hot-blooded and reactive. Initially, it was a spontaneous and defensive response to the military coup which was subsequently intensified by news brought by refugees of military atrocities and by rebel bombing raids. It is difficult to see how the violence in the Republican zone could have happened without the military coup which effectively removed all of the restraints of civilized society. The collapse of the structures of law and order as a result of the coup thus permitted both an explosion of blind millenarian revenge (the built-in resentment of centuries of oppression) and the irresponsible criminality of those let out of jail or of those individuals never previously daring to give free rein to their instincts. In addition, as in any war, there was the real military necessity of combating the enemy within.

There is no doubt that hostility intensified on both sides as the Civil War progressed, fed by outrage and a desire for revenge as news of what was happening on the other side filtered through. Nevertheless, it is also clear that, from the first moments, there was a level of hatred at work that sprang forth ready formed from the army in the North African outpost of Ceuta on the night of 17 July 1936 or from the Republican populace on 19 July at the Cuartel de la Montaña barracks in Madrid. The first part of the book explains how those enmities were fomented. Polarization ensued from the right’s determination to block the reforming ambitions of the democratic regime established in April 1931, the Second Republic. The obstruction of reform led to an ever more radicalized response by the left. At the same time, rightist theological and racial theories were elaborated to justify the intervention of the military and the destruction of the left.

In the case of the military rebels, a programme of terror and extermination was central to their planning and preparations. Because of the numerical superiority of the urban and rural working classes, they believed that the immediate imposition of a reign of terror was crucial. With the use of forces brutalized in the colonial wars in Africa, backed up by local landowners, this process was supervised in the south by General Queipo de Llano. In the significantly different regions of Navarre, Galicia, Old Castile and León, deeply conservative areas where the military coup was almost immediately successful and left-wing resistance minimal, the application of terror under the supervision of General Mola was disproportionately severe.

The exterminatory objectives of the rebels, if not their military capacities, found an echo on the extreme left, particularly in the anarchist movement, in rhetoric about the need for ‘purification’ of a corrupt society. In Republican-held areas, the underlying hatreds deriving from misery, hunger and exploitation exploded in a disorganized terror, particularly in Barcelona and Madrid. Inevitably, the targets were not just the military personnel identified with the revolt but also the wealthy, the bankers, the industrialists and the landowners who were regarded as the instruments of oppression. It was directed too, often with greater ferocity, at the clergy who were seen as the cronies of the rich, legitimizing injustice while the Church accumulated fabulous wealth. Unlike the systematic repression unleashed by the rebels as an instrument of policy, this random violence took place despite, not because of, the Republican authorities. Indeed, as a result of the efforts of successive Republican governments to re-establish public order, the left-wing repression was restrained and was largely at an end by December 1936.

Two of the bloodiest episodes in the Spanish Civil War, which are closely interrelated, concern the siege of Madrid by the rebels and the capital’s defence. Franco’s Africanista forces, the so-called ‘Column of Death’, left a trail of slaughter as they conquered towns and villages along their route from Seville to the capital. Having thus announced what Madrid could expect if surrender was not immediate, the consequence was that those responsible for the defence of the city made the decision to evacuate right-wing prisoners, particularly army officers who had sworn to join the rebel forces as soon as they could. The implementation of that decision led to the notorious massacres of right-wingers at Paracuellos on the outskirts of Madrid.

By the end of 1936, two differing concepts of the war had evolved. The Republic was on the defensive both against Franco and against enemies within. Such enemies included not just the burgeoning rebel fifth column, dedicated to spying, sabotage and spreading defeatism and despondency. Threats to the international image of the Republic and indeed to its war effort were also seen in the revolutionary ambitions of the anarchist movement, consisting of its trade union, the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo, and its activist wing, the Federación Anarquista Ibérica. The anti-Stalinist Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista was equally determined to make a priority of revolution. Both thus became targets of the same security apparatus which had put a stop to the uncontrolled repression of the first months. On the rebel side, the rapid advance of the African columns was replaced by Franco’s deliberately ponderous war of annihilation through the Basque Country, Santander, Asturias, Aragon and Catalonia. His war effort was conceived ever more as an investment in terror which would facilitate the establishment of his dictatorship. The post-war machinery of trials, executions, prisons and concentration camps consolidated that investment.

The intention was to ensure that establishment interests would never again be challenged as they had been from 1931 to 1936 by the democratic reforms of the Second Republic. When the clergy justified and the military implemented General Mola’s call for the elimination of ‘those who do not think as we do’, they were not engaged in an intellectual or ethical crusade. The defence of establishment interests was assumed to require the eradication of the ‘thinking’ of progressive liberal and left-wing elements. They had questioned the central tenets of the right which could be summed up in the slogan of the major Catholic party, the CEDA (Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas – or Spanish Confederation of Autonomous Right-Wing Groups) – ‘Religion, Fatherland, Family, Order, Work, Property’, the untouchable elements of social and economic life in Spain before 1931. ‘Religion’ referred to the Catholic Church’s monopoly of education and religious practice. ‘Fatherland’ meant no challenge to Spanish centralism from the regional nationalisms. ‘Family’ denoted the subservient position of women and the prohibition of divorce. ‘Order’ meant no toleration of public protest. ‘Work’ referred to the duties of the labouring masses. ‘Property’ meant the privileges of the landowners whose position must remain unchallenged. Sometimes, the word ‘hierarchy’ was included in the list to emphasize that the existing social order was sacrosanct. To protect all of these tenets, in the areas occupied by the rebels, the immediate victims were not just schoolteachers, Freemasons, liberal doctors and lawyers, intellectuals and trade union leaders – those who might have propagated ideas. The killing also extended to all those who might have been influenced by their ideas: the trade unionists, those who didn’t attend Mass, those suspected of voting in February 1936 for the left-wing electoral coalition, the Popular Front, and the women who had been given the vote and the right to divorce.

What all this meant in terms of numbers of deaths is still impossible to say with finality, although the broad lines are clear. Accordingly, indicative figures are frequently given in the book, drawing on the massive research carried out all over Spain in recent years by large numbers of local historians. However, despite their remarkable achievements, it is still not possible to present definitive figures for the overall number of those killed behind the lines, especially in the rebel zone. The objective should always be, as far as is possible, to base figures for those killed in both zones on the named dead. Thanks to the efforts of the Republican authorities at the time to identify bodies and because of subsequent investigations by the Francoist state, the numbers of those murdered or executed in the Republican zone are known with relative precision. The most reliable recent figure, produced by the foremost expert on the subject, José Luis Ledesma, is 49,272. However, uncertainty over the scale of the killings in Republican Madrid could see that figure rise.

Even for areas where reliable studies exist, new information and excavations of common graves see the numbers being revised constantly, albeit within relatively small parameters.

In contrast, the calculation of numbers of Republican victims of rebel violence has faced innumerable difficulties. Nineteen-sixty-five was the year in which Francoists began to think the unthinkable, that the Caudillo was not immortal, and that preparations had to be made for the future. It was not until 1985 that the Spanish government began to take belated and hesitant action to protect the nation’s archival resources. Millions of documents were lost during those crucial twenty years, including the archives of the Franco regime’s single party, the fascist Falange, of provincial police headquarters, of prisons and of the main Francoist local authority, the Civil Governors. Convoys of trucks removed the ‘judicial’ records of the repression. As well as the deliberate destruction of archives, there were also ‘inadvertent’ losses when some town councils sold their archives by the ton as waste paper for recycling.

Serious investigation was not possible until after the death of Franco in 1975. When researchers began the task, they were confronted not only with the deliberate destruction of much archival material by the Francoist authorities but also with the fact that many deaths had simply been registered either falsely or not at all. In addition to the concealment of crimes by the dictatorship was the continued fear of witnesses about coming forward and the obstruction of research, especially in the provinces of Old Castile. Archival material has mysteriously disappeared and frequently local officials have refused to permit consultation of the civilian registry.

Many executions by the military rebels were given a veneer of pseudo-legality by trials, although they were effectively little different from extra-judicial murder. Death sentences were handed out after procedures lasting minutes in which the accused were not allowed to speak.

The deaths of those killed in what the rebels called ‘cleansing and punishment operations’ were given the flimsiest legal justification by being registered as ‘by dint of the application of the declaration of martial law’ (‘por aplicación del bando de Guerra’). This was meant to legalize the summary execution of those who resisted the military take-over. The collateral deaths of many innocent people, unarmed and not offering any resistance, were also registered in this way. Then there were the executions of those registered as killed ‘without trial’ in reference to those who were discovered harbouring a fugitive, and so were shot just on military orders. There was also a systematic effort to conceal what had happened. Prisoners were taken far from their home towns, executed and buried in unmarked mass graves.

Finally, there is the fact that a substantial number of deaths were not registered in any way. This was the case with many of those who fled before Franco’s African columns as they headed from Seville to Madrid. As each town or village was occupied, among those killed were refugees from elsewhere. Since they carried no papers, their names or places of origin were unknown. It may never be possible to calculate the exact numbers murdered in the open fields by squads of mounted Falangists and extreme right-wing monarchists of the so-called Carlist movement. It is equally impossible to ascertain the fate of the thousands of refugees from Western Andalusia who died in the exodus after the fall of Málaga in 1937 or of those from all over Spain who had taken refuge in Barcelona only to die in the flight to the French border in 1939 or of those who committed suicide after waiting in vain for evacuation from the Mediterranean ports.

Nevertheless, the huge amount of research that has been carried out makes it possible to state that, broadly speaking, the repression by the rebels was about three times greater than that which took place in the Republican zone. The currently most reliable, yet still tentative, figure for deaths at the hands of the military rebels and their supporters is 130,199. However, it is unlikely that such deaths were fewer than 150,000 and they could well be more. Some areas have been studied only partially; others hardly at all. In several areas, which spent time in both zones, and for which the figures are known with some precision, the differences between the numbers of deaths at the hands of Republicans and at the hands of rebels are shocking. To give some examples, in Badajoz, there were 1,437 victims of the left as against 8,914 victims of the rebels; in Seville, 447 victims of the left, 12,507 victims of the rebels; in Cádiz, 97 victims of the left, 3,071 victims of the rebels; and in Huelva, 101 victims of the left, 6,019 victims of the rebels. In places where there was no Republican violence, the figures for rebel killings are almost incredible, for example Navarre, 3,280, La Rioja, 1,977. In most places where the Republican repression was the greater, like Alicante, Girona or Teruel, the differences are in the hundreds.

The exception is Madrid. The killings throughout the war when the capital was under Republican control seem to have been nearer three times those carried out after the rebel occupation. However, precise calculation is rendered difficult by the fact that the most frequently quoted figure for the post-war repression in Madrid, of 2,663 deaths, is based on a study of those executed and buried in only one cemetery, the Almudena or Cementerio del Este.

Although exceeded by the violence exercised by the Francoists, the repression in the Republican zone before it was stopped by the Popular Front government was nonetheless horrifying. Its scale and nature necessarily varied, with the highest figures being recorded for the largely Socialist south of Toledo and the anarchist-dominated area from the south of Zaragoza, through Teruel into western Tarragona.

In Toledo, 3,152 rightists were killed, of whom 10 per cent were members of the clergy (nearly half of the province’s clergy).

In Cuenca, the total deaths were 516 (of whom thirty-six, or 7 per cent of the total killed, were priests – nearly a quarter of the province’s clergy).

The figure for deaths in Republican Catalonia, according to the exhaustive study by Josep Maria Solé i Sabaté and Joan Vilarroyo i Font, was 8,360. This figure corresponds closely to the conclusions reached by a commission created by the Generalitat de Catalunya (the Catalan regional government) in 1937. Part of the efforts of the Republican authorities to register deaths, it was led by a judge, Bertran de Quintana, and investigated all deaths behind the lines in order to instigate measures against those responsible for extra-judicial executions.

Such a procedure would have been inconceivable in the rebel zone.

Recent scholarship, not only for Catalonia but also for most of Republican Spain, has dramatically dismantled the propagandistic allegations made by the rebels at the time. On 18 July 1938 in Burgos, Franco himself claimed that 54,000 people had been killed in Catalonia. In the same speech, he alleged that 70,000 had been murdered in Madrid and 20,000 in Valencia. On the same day, he told a reporter there had already been a total of 470,000 murders in the Republican zone.

To prove the scale of Republican iniquity to the world, on 26 April 1940 he set up a massive state investigation, the Causa General, ‘to gather trustworthy information’ to ascertain the true scale of the crimes committed in the Republican zone. Denunciation and exaggeration were encouraged. Thus it came as a desperate disappointment to Franco when, on the basis of the information gathered, the Causa General concluded that the number of deaths was 85,940. Although inflated and including many duplications, this figure was still so far below Franco’s claims that, for over a quarter of a century, it was omitted from editions of the published résumé of the Causa General’s findings.

A central, yet under-estimated, part of the repression carried out by the rebels – the systematic persecution of women – is not susceptible to statistical analysis. Murder, torture and rape were generalized punishments for the gender liberation embraced by many, but not all, liberal and left-wing women during the Republican period. Those who came out of prison alive suffered deep lifelong physical and psychological problems. Thousands of others were subjected to rape and other sexual abuses, the humiliation of head shaving and public soiling after the forced ingestion of castor oil. For most Republican women, there were also the terrible economic and psychological problems of having their husbands, fathers, brothers and sons murdered or forced to flee, which often saw the wives themselves arrested in efforts to get them to reveal the whereabouts of their menfolk. In contrast, despite frequent assumptions that the raping of nuns was common in Republican Spain, there was relatively little equivalent abuse of women there. That is not to say that it did not take place. The sexual molestation of around one dozen nuns and the deaths of 296, just over 1.3 per cent of the female clergy, is shocking but of a notably lower order of magnitude than the fate of women in the rebel zone.

That is not entirely surprising given that respect for women was built into the Republic’s reforming programme.

The statistical vision of the Spanish holocaust is not only flawed, incomplete and unlikely ever to be complete. It also fails to capture the intense horror that lies behind the numbers. The account that follows includes many stories of individuals, of men, women and children from both sides. It introduces some specific but representative cases of victims and perpetrators from all over the country. It is hoped thereby to convey the suffering unleashed upon their own fellow citizens by the arrogance and brutality of the officers who rose up on 17 July 1936. They provoked a war that was unnecessary and whose consequences still reverberate bitterly in Spain today.

PART ONE

1

Social War Begins, 1931–1933

On 18 July 1936, on hearing of the military uprising in Morocco, an aristocratic landowner lined up the labourers on his estate to the south-west of Salamanca and shot six of them as a lesson to the others. The Conde de Alba de Yeltes, Gonzalo de Aguilera y Munro, a retired cavalry officer, joined the press service of the rebel forces during the Civil War and boasted of his crime to foreign visitors.

Although his alleged atrocity was extreme, the sentiments behind it were not unrepresentative of the hatreds that had smouldered in the Spanish countryside over the twenty years before the military uprising of 1936. Aguilera’s cold and calculated violence reflected the belief, common among the rural upper classes, that the landless labourers were sub-human. This attitude had become common among the big landowners since a series of sporadic uprisings by hungry day-labourers in the regions of Spain dominated by huge estates (latifundios). Taking place between 1918 and 1921, a period of bitter social conflict known thereafter as the trienio bolchevique (three Bolshevik years), these insurrections had been crushed by the traditional defenders of the rural oligarchy, the Civil Guard and the army. Previously, there had been an uneasy truce within which the wretched lives of the landless day-labourers (jornaleros or braceros) were occasionally relieved by the patronizing gestures of the owners – the gift of food or a blind eye turned to rabbit poaching or to the gathering of windfall crops. The violence of the conflicts had outraged the landlords, who would never forgive the insubordination of the braceros they considered to be an inferior species. Accordingly, the paternalism which had somewhat mitigated the daily brutality of the day-labourers’ lives came to an abrupt end.

The agrarian oligarchy, in an unequal partnership with the industrial and financial bourgeoisie, was traditionally the dominant force in Spanish capitalism. Its monopoly of power began to be challenged on two sides in the course of the painful and uneven process of industrialization. The prosperity enjoyed by neutral Spain during the First World War emboldened industrialists and bankers to jostle with the great landowners for political position. However, with both menaced by a militant industrial proletariat, they soon rebuilt a defensive alliance. In August 1917, the left’s feeble revolutionary threat was bloodily smothered by the army. Thereafter, until 1923, when the army intervened again, social ferment occasionally bordered on undeclared civil war. In the south, there were the rural uprisings of the ‘three Bolshevik years’. In the north, the industrialists of Catalonia, the Basque Country and Asturias, having tried to ride the immediate post-war recession with wage-cuts and layoffs, faced violent strikes and, in Barcelona, a terrorist spiral of provocations and reprisals.

In the consequent atmosphere of uncertainty and anxiety, there was a ready middle-class audience for the notion long since disseminated by extreme right-wing Catholics that a secret alliance of Jews, Freemasons and the Communist Third International was conspiring to destroy Christian Europe, with Spain as a principal target. In Catholic Spain, the idea that there was an evil Jewish conspiracy to destroy Christianity had emerged in the early Middle Ages. In the nineteenth century, the Spanish extreme right resurrected it to discredit the liberals whom they viewed as responsible for social changes that were damaging their interests. In this paranoid fantasy, Freemasons were smeared as tools of the Jews (of whom there were virtually none) in a sinister plot to establish Jewish tyranny over the Christian world.

As the nineteenth century drew to a close, such views were expressed with ever increasing vehemence. They were a response to the kaleidoscopic processes of rapid economic growth, social dislocation, regionalist agitations, a bourgeois reform movement and the emergence of trade unions and left-wing parties. An explanation for the destabilization of Spanish society and the attendant collapse of the relative certainties of a predominantly rural society was found in a deeply alarming, yet somehow comforting, assertion that shifted the blame on to an identifiable and foreign enemy. It was alleged that, using Freemasons as their willing intermediaries, the Jews controlled the economy, politics, the press, literature and the entertainment world through which they propagated immorality and the brutalization of the masses. Such views had long been peddled by El Siglo Futuro, the daily newspaper of the deeply reactionary Carlist Traditionalist Communion. In 1912, the National Anti-Masonic and Anti-Semitic League had been founded by José Ignacio de Urbina with the support of twenty-two Spanish bishops. The Bishop of Almería wrote that ‘everything is ready for the decisive battle that must be unleashed between the children of light and the children of darkness, between Catholicism and Judaism, between Christ and the Devil’.

That there was never any hard evidence was put down to the cleverness and colossal power of the enemy, evil itself.

In Spain, as in other European countries, anti-Semitism had reached even greater intensity after 1917. It was taken as axiomatic that socialism was a Jewish creation and that the Russian revolution had been financed by Jewish capital, an idea given a spurious credibility by the Jewish origins of prominent Bolsheviks such as Trotsky, Martov and Dan. Spain’s middle and upper classes were chilled, and outraged, by the various revolutionary upheavals that threatened them between 1917 and 1923. The fears of the elite were somewhat calmed in September 1923, when the army intervened again and a dictatorship was established by General Miguel Primo de Rivera. As Captain General of Barcelona, Primo de Rivera was the ally of Catalan textile barons and understood their sense of being under threat from their anarchist workforce. Moreover, coming from a substantial landowning family in Jérez, he also appreciated the fears of the big southern landowners or latifundistas. He was thus the ideal praetorian defender of the reactionary coalition of industrialists and landowners consolidated after 1917. While Primo de Rivera remained in power, he offered security to the middle and upper classes. Nevertheless, his ideologues worked hard to build the notion that in Spain two bitterly hostile social, political and, indeed, moral groupings were locked in a fight to the death. Specifically, in a pre-echo of the function that they would also fulfil for Franco, these propagandists stressed the dangers faced from Jews, Freemasons and leftists.

These ideas essentially delegitimized the entire spectrum of the left, from middle-class liberal democrats, via Socialists and regional nationalists, to anarchists and Communists. This was done by blurring distinctions between them and by denying their right to be considered Spanish. The denunciations of this ‘anti-Spain’ were publicized through the right-wing press and the regime’s single party, the Unión Patriótica, as well as through civic organizations and the education system. These notions served to generate satisfaction with the dictatorship as a bulwark against the perceived Bolshevik threat. Starting from the premise that the world was divided into ‘national alliances and Soviet alliances’, the influential right-wing poet José María Pemán declared that ‘the time has come for Spanish society to choose between Jesus and Barabbas’. He claimed that the masses were ‘either Christian or anarchic and destructive’ and the nation was divided between an anti-Spain made up of everything that was heterodox and foreign and the real Spain of traditional religious and monarchical values.

Another senior propagandist of the Primo de Rivera regime, José Pemartín, linked, like his cousin Pemán, to the extreme right in Seville, also believed that Spain was under attack by an international conspiracy masterminded by Freemasonry, ‘the eternal enemy of all the world’s governments of order’. He dismissed the left, in generalized terms, as ‘the dogmatists deluded by what they think are modern, democratic and European ideas, universal suffrage, the sovereign parliament, etc. They are beyond redemption. They are made mentally ill by the worst of tyrannies, ideocracy or the tyranny of certain ideas.’ It was the duty of the army to defend Spain against these attacks.

Despite his temporary success in anaesthetizing the anxieties of the middle and ruling classes, Primo de Rivera’s dictatorship did not last. His benevolent attempt to temper authoritarianism with paternalism inadvertently alienated landowners, industrialists, the Church hierarchy and some of the elite officer corps of the army. Most dramatically, his attempts to reform military promotion procedures ensured that the army would stand aside when a great electoral coalition of Socialists and middle-class Republicans swept to power on 14 April 1931. After the dictator’s departure in January 1930, one of the first to take up the defence of establishment interests was Dr José María Albiñana, an eccentric Valencian neurologist and frenetic admirer of Primo de Rivera.

The author of more than twenty novels and books on neurasthenia, religion, the history and philosophy of medicine and Spanish politics, and a number of mildly imperialist works about Mexico, Albiñana was convinced that there was a secret alliance working in foreign obscurity in order to destroy Spain. In February 1930, he distributed tens of thousands of copies of his Manifiesto por el Honor de España. In it, he had declared that ‘there exists a Masonic Soviet which dishonours Spain in the eyes of the world by reviving the black legend and other infamies forged by the eternal hidden enemies of our fatherland. This Soviet, made up of heartless persons, is backed by spiteful politicians who, to avenge offences against themselves, go abroad to vomit insults against Spain’. This was a reference to the Republicans exiled by the dictatorship. Two months later, he launched his ‘exclusively Spanish Nationalist Party’ whose objective was to ‘annihilate the internal enemies of the fatherland’. A fascist image was provided by its blue-shirted, Roman-saluting Legionaries of Spain, a ‘citizen volunteer force to act directly, explosively and expeditiously against any initiative which attacks or diminishes the prestige of the fatherland’.

Albiñana was merely one of the first to argue that the fall of the monarchy was the first step in the Jewish–Masonic–Bolshevik conspiracy to take over Spain. Such ideas would feed the extreme rightist paranoia that met the establishment of the Second Republic. The passing of political power to the Socialist Party (PSOE – Partido Socialista Obrero Español) and its urban middle-class allies, the lawyers and intellectuals of the various Republican parties, sent shivers of horror through right-wing Spain. The Republican–Socialist coalition intended to use its suddenly acquired share of state power to implement a far-reaching programme to create a modern Spain by destroying the reactionary influence of the Church, eradicating militarism and improving the immediate conditions of the wretched day-labourers with agrarian reform.

This huge agenda inevitably raised the expectations of the urban and rural proletariats while provoking the fear and the determined enmity of the Church, the armed forces and the landowning and industrial oligarchies. The passage from the hatreds of 1917 –23 to the widespread violence that engulfed Spain after 1936 was long and complex but it began to speed up dramatically in the spring of 1931. The fears and hatreds of the rich found, as always, their first line of defence in the Civil Guard. However, as landowners blocked attempts at reform, the frustrated expectations of hungry day-labourers could be contained only by increasing brutality.

Many on the right took the establishment of the Republic as proof that Spain was the second front in the war against world revolution – a notion fed by numerous clashes between the forces of order and workers of the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT), the anarchist union. Resolute action against the extreme left by the Minister of the Interior, Miguel Maura, did not deter the Carlist newspaper El Siglo Futuro from attacking the government and claiming that progressive Republican legislation was ordered from abroad. It declared in June 1931 that three of the most conservative ministers, the premier, Niceto Alcalá Zamora, Miguel Maura and the Minister of Justice, Fernando de los Ríos Urruti, were Jews and that the Republic itself had been brought about as a result of a Jewish conspiracy. The more moderate Catholic mass-circulation daily El Debate referred to de los Ríos as ‘the rabbi’. The Editorial Católica, which owned an influential chain of newspapers including El Debate, soon began to publish the virulently anti-Semitic and anti-Masonic magazines Gracia y Justicia and Los Hijos del Pueblo. The editor of the scurrilously satirical Gracia y Justicia was Manuel Delgado Barreto, a one-time collaborator of the dictator General Primo de Rivera, a friend of his son José Antonio and an early sponsor of the Falange. It would reach a weekly circulation of 200,000 copies.

The Republic would face violent resistance not only from the extreme right but also from the extreme left. The anarcho-syndicalist CNT recognized that many of its militants had voted for the Republican–Socialist coalition in the municipal elections of 12 April and that its arrival had raised the people’s hopes. As one leading anarchist put it, they were ‘like children with new shoes’. The CNT leadership, however, expecting the Republic to change nothing, aspired merely to propagate its revolutionary objectives and to pursue its fierce rivalry with the Socialist Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT), which it regarded as a scab union because of its collaboration with the Primo de Rivera regime. In a period of mass unemployment, with large numbers of migrant workers returning from overseas and unskilled construction workers left without work by the ending of the great public works projects of the dictatorship, the labour market was potentially explosive. This was a situation that would be exploited by the hard-line anarchists of the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI) who argued that the Republic, like the monarchy, was just an instrument of the bourgeoisie. The brief honeymoon period came to an end when CNT–FAI demonstrations on 1 May were repressed violently by the forces of order.

In late May, a group of nearly one thousand strikers from the port of Pasajes descended on San Sebastián with the apparent intention of looting the wealthy shopping districts. Having been warned in advance, the Minister of the Interior, Miguel Maura, deployed the Civil Guard at the entrance to the city. They repelled the attack at the cost of eight dead and many wounded. Then, in early July, the CNT launched a nationwide strike in the telephone system, largely as a challenge to the government. It was defeated by harsh police measures and strike-breaking by workers of the Socialist UGT who refused to join the CNT in what they saw as a sterile struggle. The Director General of Security, the sleek and portly Ángel Galarza of the Radical-Socialist Party, ordered that anyone seen trying to damage the installations of the telephone company should be shot. Maura and Galarza were understandably trying to maintain the confidence of the middle classes. Inevitably, their stance consolidated the violent hostility of the CNT towards both the Republic and the UGT.

For the Republican–Socialist cabinet, the subversive activities of the CNT constituted rebellion. For the CNT, legitimate strikes and demonstrations were being crushed by dictatorial methods indistinguishable from those used by the monarchy. On 21 July 1931, the cabinet agreed on the need for ‘an urgent and severe remedy’. Maura outlined a proposal for ‘a legal instrument of repression’ and the Socialist Minister of Labour, Francisco Largo Caballero, proposed a decree to make strikes illegal. The two decrees would eventually be combined on 22 October into the Law for the Defence of the Republic, a measure enthusiastically supported by the Socialist members of the government not least because it was perceived as directed against their CNT rivals.

It made little difference to the right, which perceived the violent social disorder of the anarchists as characteristic of the entire left, including the Socialists who denounced it and the Republican authorities who crushed it.

What mattered to the right was that the Civil Guard and the army lined up in defence of the existing economic order against the anarchists. Traditionally, the bulk of the army officer corps perceived the prevention of political and economic change as one of its primordial tasks. Now, the Republic would attempt to reform the military, bringing both its costs and its mentalities into line with Spain’s changed circumstances. A central part of that project would be the streamlining of a massively swollen officer corps. The tough and uncompromising colonial officers, the so-called Africanistas, having benefited from irregular and vertiginous battlefield promotions, would be the most affected. Their opposition to Republican reforms would inaugurate a process whereby the violence of Spain’s recent colonial history found a route back into the metropolis. The rigours and horrors of the Moroccan tribal wars between 1909 and 1925 had brutalized them. Morocco had also given them a beleaguered sense that, in their commitment to fighting to defend the colony, they alone were concerned with the fate of the Patria. Long before 1931, this had developed into a deep contempt both for professional politicians and for the pacifist left-wing masses that the Africanistas regarded as obstacles to the successful execution of their patriotic mission.

The repressive role of both the army and the Civil Guard in Spain’s long-standing social conflicts, particularly in rural areas, was perceived as central to that patriotic duty. However, between 1931 and 1936, several linked factors would provide the military with pervasive justifications for the use of violence against the left. The first was the Republic’s attempt to break the power of the Catholic Church. On 13 October 1931, the Minister of War, and later Prime Minister and President, Manuel Azaña, stated that ‘Spain has ceased to be Catholic.’

Even if this was true, Spain remained a country with many pious and sincere Catholics. Now, the Republic’s anti-clerical legislation would provide an apparent justification for the virulent enmity of those who already had ample motive to see it destroyed. The bilious rhetoric of the Jewish–Masonic–Bolshevik conspiracy was immediately pressed into service. Moreover, the gratuitous nature of some anti-clerical measures would help recruit many ordinary Catholics to the cause of the rich.

The religious issue would nourish a second crucial factor in fostering right-wing violence. This was the immensely successful propagation of theories that left-wingers and liberals were neither really Spanish nor even really human and that, as a threat to the nation’s existence, they should be exterminated. In books that sold by the tens of thousands, in daily newspapers and weekly magazines, the idea was hammered home that the Second Republic was foreign and sinister and must be destroyed. This notion, which found fertile ground in right-wing fear, was based on the contention that the Republic was the product of a conspiracy masterminded by Jews, and carried out by Freemasons through left-wing lackeys. The idea of this powerful international conspiracy – or contubernio (filthy cohabitation), one of Franco’s favourite words – justified any means necessary for what was presented as national survival. The intellectuals and priests who developed such ideas were able to connect with the latifundistas’ hatred for the landless day-labourers or jornaleros and the urban bourgeoisie’s fear of the unemployed. The Salamanca landowner Gonzalo de Aguilera y Munro, like many army officers and priests, was a voracious reader of such literature.

Another factor which fomented violence was the reaction of the landowners to the Second Republic’s various attempts at agrarian reform. In the province of Salamanca, the leaders of the local Bloque Agrario, the landowners’ party, Ernesto Castaño and José Lamamié de Clairac, incited their members not to pay taxes nor to plant crops. Such intransigence radicalized the landless labourers.

Across the areas of great estates (latifundios) in southern Spain, Republican legislation governing labour issues in the countryside was systematically flouted. Despite the decree of 7 May 1931 of obligatory cultivation, unionized labour was ‘locked out’ either by land being left uncultivated or by simply being refused work and told to comed República (literally ‘eat the Republic’, which was a way of saying ‘let the Republic feed you’). Despite the decree of 1 July 1931 imposing the eight-hour day in agriculture, sixteen-hour working days from sun-up to sun-down prevailed with no extra hours being paid. Indeed, starvation wages were paid to those who were hired. Although there were tens of thousands of unemployed landless labourers in the south, landowners proclaimed that unemployment was an invention of the Republic.

In Jaén, the gathering of acorns, normally kept for pigs, or of windfall olives, the watering of beasts and even the gathering of firewood were denounced as ‘collective kleptomania’.

Hungry peasants caught doing such things were savagely beaten by the Civil Guard or by armed estate guards.

Their expectations raised by the coming of the new regime, the day-labourers were no longer as supine and fatalistic as had often been the case. As their hopes were frustrated by the obstructive tactics of the latifundistas, the desperation of the jornaleros could be controlled only by an intensification of the violence of the Civil Guard. The ordinary Civil Guards themselves often resorted to their firearms in panic, fearful of being outnumbered by angry mobs of labourers. Incidents of the theft of crops and game were reported with outrage by the right-wing press. Firearms were used against workers, and their deaths were reported with equal indignation in the left-wing press. In Corral de Almaguer (Toledo), starving jornaleros tried to break a local lock-out by invading estates and starting to work them. The Civil Guard intervened on behalf of the owners, killing five workers and wounding another seven. On 27 September 1931, for instance, in Palacios Rubios near Peñaranda de Bracamonte in the province of Salamanca, the Civil Guard opened fire on a group of men, women and children celebrating the successful end to a strike. The Civil Guard began to shoot when the villagers started to dance in front of the parish priest’s house. Two workers were killed immediately and two more died shortly afterwards.

Immense bitterness was provoked by the case. In July 1933, on behalf of the Salamanca branch of the UGT landworkers’ federation (Federación Nacional de Trabajadores de la Tierra), the editor of its newspaper Tierra y Trabajo, José Andrés y Mansó, brought a private prosecution against a Civil Guard corporal, Francisco Jiménez Cuesta, on four counts of homicide and another three of wounding. Jiménez Cuesta was successfully defended by the leader of the authoritarian Catholic party, the CEDA, José María Gil Robles. Andrés y Mansó would be murdered by Falangists at the end of July 1936.

In Salamanca and elsewhere, there were regular acts of violence perpetrated against trade union members and landowners – a seventy-year-old beaten to death by the rifle butts of the Civil Guard in Burgos, a property-owner badly hurt in Villanueva de Córdoba. Very often these incidents, which were not confined to the south but also proliferated in the three provinces of Aragon, began with invasions of estates. Groups of landless labourers would go to a landowner and ask for work or sometimes carry out agricultural tasks and then threateningly demand payment. More often than not, they would be driven off by the Civil Guard or by gunmen employed by the owners.

In fact, what the landowners were doing was merely one element of unequivocal right-wing hostility to the new regime. They occupied the front line of defence against the reforming ambitions of the Republic. There were equally vehement responses to the religious and military legislation of the new regime. Indeed, all three issues were often linked, with many army officers emanating from Catholic landholding families. All these elements found a political voice in several newly emerged political groups. Most extreme among them, and openly committed to the earliest possible destruction of the Republic, were two monarchist organizations, the Carlist Comunión Tradicionalista and Acción Española, founded by supporters of the recently departed King Alfonso XIII as a ‘school of modern counter-revolutionary thought’. Within hours of the Republic being declared, monarchist plotters had begun collecting money to create a journal to propagate the legitimacy of a rising against the Republic, to inject a spirit of rebellion in the army and to found a party of ostensible legality as a front for meetings, fund-raising and conspiracy against the Republic. The journal Acción Española would also peddle the idea of the sinister alliance of Jews, Freemasons and leftists. Within a month, its founders had collected substantial funds for the projected uprising. Their first effort would be the military coup of 10 August 1932. And its failure would lead to a determination to ensure that the next attempt would be better financed and entirely successful.

Somewhat more moderate was the legalist Acción Nacional, later renamed Acción Popular, which was prepared to try to defend right-wing interests within Republican legality. Extremists or ‘catastrophists’ and ‘moderates’ shared many of the same ideas. However, after the failed military coup of August 1932, they would split over the efficacy of armed conspiracy against the Republic. Acción Española formed its own political party, Renovación Española, and Acción Popular did the same, gathering a number of like-minded groups into the Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas.

Within a year, the ranks of the ‘catastrophists’ had been swelled by the creation of various fascist organizations. What all had in common was that they completely denied the democratic legitimacy of the Republic. Despite the legalist façade of Acción Popular and the CEDA, its leaders would frequently and unrestrainedly proclaim that violence against the Republic was perfectly justifiable.

Barely three weeks after the establishment of the new regime, at a time when the government was notable mainly for its timidity in social questions, Acción Nacional had been created as ‘an organization for social defence’. It was the creation of Ángel Herrera Oria, editor of the militantly Catholic (and hitherto monarchist) daily El Debate. A shrewd political strategist, Herrera Oria would be the brains behind political Catholicism in the early years of the Second Republic. Acción Nacional brought together two organizations of the right that had combated the rising power of the urban and rural working class for the previous twenty years. Its leaders came from the Asociación Católica Nacional de Propagandistas, an elite Jesuit-influenced organization of about five hundred prominent and talented Catholic rightists with influence in the press, the judiciary and the professions. Its rank-and-file support would be found within the Confederación Nacional Católico-Agraria, a mass political organization which proclaimed its ‘total submission to the ecclesiastic authorities’. Established to resist the growth of left-wing organizations, the CNCA was strong among the Catholic smallholding peasantry in north and central Spain.

Acción Nacional’s manifesto declared that ‘the advance guards of Soviet Communism’ were already clambering on the ruins of the monarchy. It denounced the respectable bourgeois politicians of the Second Republic as weak and incapable of controlling the masses. ‘They are the masses that deny God and, in consequence, the basic principles of Christian morality; that proclaim, against the sanctity of the family, the instability of free love; that substitute private property, the basis and the motor of the welfare of individuals and of collective wealth, by a universal proletariat at the orders of the State.’ In addition, there was ‘the lunacy of Basque and Catalan ultra-nationalism, determined, irrespective of its sweet words, to destroy national unity’. Acción Nacional unequivocally announced itself as the negation of everything for which, it claimed, the Republic stood. With the battle cry ‘Religion, Fatherland, Family, Order, Work, Property’, it declared that ‘the social battle is being waged in our time to decide the triumph or extermination of these eternal principles. In truth, this will not be decided in a single combat; what is being unleashed in Spain is a war, and it will be a long one.’

By 1933, when Acción Popular had developed into the CEDA, its analysis of the Republic was even less circumspect: ‘the rabble, always irresponsible because of their lack of values, took over the strongholds of government’. Even for Herrera Oria’s legalist organization, the Republic was created when ‘the contagious madness of the most inflamed extremists sparked a fire in the inflammable material of the heartless, the perverted, the rebellious, the insane’. The supporters of the Republic were sub-human and, like pestilent vermin, should be eliminated: ‘The sewers opened their sluice gates and the dregs of society inundated the streets and squares, convulsing and shuddering like epileptics.’

All over Europe, endangered elites were mobilizing mass support by stirring up fears of a left presented as ‘foreign’, a disease that threatened the nation and required a crusade of national purification.

Both at the time and later, the right-wing determination to annihilate the Republic was justified as a response to its anti-clericalism. However, as had been amply demonstrated by its enthusiastic support for the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera, the right hated the Republic for being democratic long before it was able to denounce it for being anti-clerical. Moreover, those who opposed the Republic on religious grounds also cited social, economic and political grounds, especially in opposition to regional autonomy.

Nevertheless, the religious issue was the occasion of intense conflict, both verbal and physical. On Sunday 10 May 1931, the inaugural meeting of the Circulo Monarquico Independiente in the Calle Alcalá ended with loudspeakers provocatively blaring out the Royal Anthem. Republican crowds returning from an afternoon concert in Madrid’s Parque del Buen Retiro were outraged. There was a riot; cars were burned and the offices of the monarchist newspaper ABC in neighbouring Calle Serrano were assaulted. The fierce popular reaction spilled over into the notorious church burnings which took place in Madrid, Málaga, Seville, Cádiz and Alicante from 10 to 12 May. This suggested how strongly ordinary people identified the Church with the monarchy and right-wing politics. The Republican press claimed that the fires were the work of provocateurs drawn from the scab union, the Sindicatos Libres. Indeed, it was claimed that, to discredit the new regime, young monarchists had distributed leaflets inciting the masses to attack religious buildings.

Even if there were agents provocateurs involved, many on the left were convinced that the Church was integral to reactionary politics in Spain and physical attacks were carried out in some places by the more hotheaded among them. In many villages in the south, priests had stones thrown at them. For those on the right, the identity of the true culprits mattered little. The church burnings confirmed and justified their prior hostility to the Republic. Nevertheless, Miguel Maura, the Minister of the Interior, commented bitterly: ‘Madrid’s Catholics did not think for a second that it was appropriate or their duty to make an appearance in the street in defence of what should have been sacred to them.’ There were serious clashes in many small towns (pueblos) where the faithful protected their churches from elements intent on profaning them. Later in May, when the provisional government decreed an end to obligatory religious education, there were many petitions in protest.

While most of Spain remained peaceful, from the earliest days of the Republic an atmosphere of undeclared civil war festered in the latifundio zones of the south and in other areas dominated by the CNT. Miguel Maura claimed that, in the five months from mid-May 1931 until his resignation in October, he had to deal with 508 revolutionary strikes. The CNT accused him of causing 108 deaths with his repressive measures.

This was demonstrated most graphically by the bloody conclusion to a period of anarchist agitation in Seville. As the culmination of a series of revolutionary strikes, the anarchist union called a general stoppage on 18 July 1931. This was directed not just at the local employers but also at the CNT’s local rivals in the Socialist Unión General Trabajadores. There were violent clashes between anarchist and Communist strikers on the one hand and blacklegs and the Civil Guard on the other. At the cabinet meeting of 21 July, the Socialist Minister of Labour, Francisco Largo Caballero, demanded that Miguel Maura take firm action to end the disorders which were damaging the Republic’s image. When the Prime Minister, Niceto Alcalá Zamora, asked if everyone was agreed that energetic measures against the CNT were called for, the cabinet assented unanimously. Maura told Azaña that he would order artillery to demolish a house from which anarchists had fired against the forces of order.

Meanwhile, on the night of 22–23 July 1931, extreme rightists were permitted to take part in the repression of the strikes in Seville. Believing that the forces of order were inadequate to deal with the problem, José Bastos Ansart, the Civil Governor, invited the landowners’ clubs, the Círculo de Labradores and the Unión Comercial, to form a paramilitary group to be known as the ‘Guardia Cívica’. This invitation was eagerly accepted by the most prominent rightists of the city, Javier Parladé Ybarra, Pedro Parias González, a retired lieutenant colonel of the cavalry and a substantial landowner, and José García Carranza, a famous bullfighter who fought as ‘Pepe el Algabeño’. Arms were collected, and the Guardia Cívica was led by a brutal Africanista, Captain Manuel Díaz Criado, known as ‘Criadillas’ (Bull’s Balls). On the night of 22 July, in the Parque de María Luisa, they shot four prisoners. On the following afternoon, the Casa Cornelio, a workers’ café in the neighbourhood of La Macarena, was, as Maura had promised Azaña, destroyed by artillery fire. Elsewhere in the province, particularly in three small towns to the south of the capital, Coria del Río, Utrera and Dos Hermanas, strikes were repressed with exceptional violence by the Civil Guard. In Dos Hermanas, after some stones had been thrown at the telephone exchange, a lorryload of Civil Guards arrived from Seville. With the local market in full swing, they opened fire, wounding several, two of whom died later. In total, seventeen people were killed in clashes in the province.

Azaña’s immediate reaction was that the events in the park ‘looked like the use of the ley de fugas’ (the pretence that prisoners were shot while trying to escape) and he blamed Maura, commenting that ‘he shoots first and then he aims’. Azaña’s reaction was influenced by the fact that Maura had recently hit him for accusing him of revealing cabinet secrets to the press. Two weeks later, he learned that the cold-blooded application of the ley de fugas was nothing to do with Maura but had been carried out by the Guardia Cívica on the orders of Díaz Criado.

The murders in the Parque de María Luisa and the shelling of the Casa Cornelio were the first in a chain of events leading to the savagery of 1936. Díaz Criado and the Guardia Cívica would play a prominent role both in the failed military coup of August 1932 and in the events of 1936.

The events in Seville and the telephone strike were symptomatic of clashes between the forces of order and the CNT throughout urban Spain. In Barcelona, in addition to the telephone conflict, a strike in the metallurgical industry saw 40,000 workers down tools in August. The activist FAI increasingly advocated insurrection to replace the bourgeois Republic with libertarian communism. Paramilitary street action directed against the police and the Civil Guard was to be at the heart of what the prominent FAI leader Juan García Oliver defined as ‘revolutionary gymnastics’. This inevitably led to bloody clashes with the forces of order and with the more moderate Socialist UGT. The consequent violence in Barcelona, Seville, Valencia, Zaragoza and Madrid, although directed against the government, was blamed by the right on the Republic.

The unease thereby fomented among the middle classes was consolidated among Catholics by the anti-clericalism of the Republic. Little distinction was made between the ferocious iconoclasm of the anarchists and the Republican–Socialist coalition’s ambition to limit the Church’s influence to the strictly religious sphere. Right-wing hostility to the Republic was mobilized fully, with clerical support, in the wake of the parliamentary debate over the proposed Republican Constitution. The text separated Church and state and introduced civil marriage and divorce. It curtailed state support for the clergy and ended, on paper at least, the religious monopoly of education. The proposed reforms were denounced by the Catholic press and from pulpits as a Godless, tyrannical and atheistic attempt to destroy the family.

The reaction of a priest from Castellón de la Plana was not uncommon. In a sermon he told his parishioners, ‘Republicans should be spat on and never spoken to. We should be prepared to fight a civil war before we tolerate the separation of Church and State. Non-religious schools do not educate men, they create savages.’

The Republic’s anti-clerical legislation was at best incautious and at worst irresponsible, perceived on the right as the fruit of Masonic-inspired hatred. Republicans felt that to create an egalitarian society, the power of the Church education system had to be replaced with nondenominational schools. Many measures were easily sidestepped. Schools run by religious personnel continued as before – the names of schools were changed, clerics adopted lay dress. Many such schools, especially those of the Jesuits, tended to be accessible only to the children of the rich. There was no middle ground. The Church’s defence of property and its indifference to social hardship inevitably aligned it with the extreme right.

Substantial popular hostility to the Republic’s plans for changes in the social, economic and religious landscape was garnered during the so-called revisionist campaign against the Constitution. Bitter right-wing opposition to the Constitution passed on 13 October was provoked by plans to advance regional autonomy for Catalonia and to introduce agrarian reform.

Nevertheless, it was the legalization of divorce and the dissolution of religious orders – seen as evil Masonic machinations – that raised Catholic ire.

During the debate on 13 October 1931, the parliamentary leader of Acción Popular, José María Gil Robles, declared to the Republican–Socialist majority in the parliament, the Cortes, ‘Today, in opposition to the Constitution, Catholic Spain takes its stand. You will bear responsibility for the spiritual war that is going to be unleashed in Spain.’ Five days later, in the Plaza de Toros de Ledesma, Gil Robles called for a crusade against the Republic.

As part of the campaign a group of Basque Traditionalists created the Association of Relatives and Friends of Religious Personnel. The Association attracted considerable support in Salamanca and Valladolid, towns notable for the ferocity of the repression during the Civil War. It published an anti-Republican bulletin, Defensa, and many anti-Republican pamphlets. It also founded the violently anti-Masonic and anti-Semitic weekly magazine Los Hijos del Pueblo under the editorship of Francisco de Luis, who would eventually run El Debate in succession to Ángel Herrera Oria. De Luis was a fervent advocate of the theory that the Spanish Republic was the plaything of an international Jewish–Masonic–Bolshevik conspiracy.

Another leading contributor to Los Hijos del Pueblo was the integrist Jesuit Father Enrique Herrera Oria, brother of Ángel. The paper’s wide circulation was in large part a reflection of the popularity of its vicious satirical cartoons attacking prominent Republican politicians. Presenting them as Jews and Freemasons, and thus part of the international conspiracy against Catholic Spain, it popularized among its readers the notion that this filthy foreign plot had to be destroyed.

The idea that leftists and liberals were not true Spaniards and therefore had to be destroyed quickly took root on the right. In early November 1931, the monarchist leader Antonio Goicoechea declared to a cheering audience in Madrid that there was to be a battle to the death between socialism and the nation.

On 8 November, the Carlist Joaquín Beunza thundered to an audience of 22,000 people in Palencia: ‘Are we men or not? Those not prepared to give their all in these moments of shameless persecution do not deserve the name Catholic. We must be ready to defend ourselves by all means, and I don’t say legal means, because all means are good for self-defence.’ Declaring the Cortes a zoo, he went on: ‘We are governed by a gang of Freemasons. And I say that against them all methods are legitimate, both legal and illegal ones.’ At the same meeting, Gil Robles declared that the government’s persecution of the Church was decided ‘in the Masonic lodges’.

Incitement to violence against the Republic and its supporters was not confined to the extreme right. The speeches of the legalist Catholic Gil Robles were every bit as belligerent and provocative as those of monarchists, Carlists and, later, Falangists. At Molina de Segura (Murcia) on New Year’s Day 1932, Gil Robles declared: ‘In 1932 we must impose our will with the force of our rightness, and with other forces if this is insufficient. The cowardice of the Right has allowed those who come from the cesspools of iniquity to take control of the destinies of the fatherland.’

The intransigence of more moderate sections of the Spanish right was revealed by the inaugural manifesto of the Juventud (youth movement) de Acción Popular which proclaimed: ‘We are men of the right … We will respect the legitimate orders of authority, but we will not tolerate the impositions of the irresponsible rabble. We will always have the courage to make ourselves respected. We declare war on communism and Freemasonry.’ In the eyes of the right, ‘communism’ included the Socialist Party and Freemasonry signified the various Republican liberal parties and their regional variants known as Left Republicans.