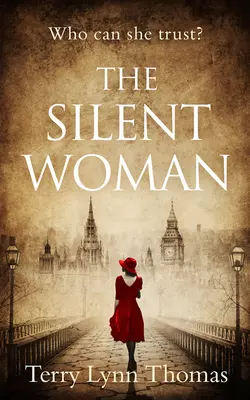

The Silent Woman: The USA TODAY BESTSELLER - a gripping historical fiction

Terry Lynn Thomas

USA Today bestseller!Would you sell your secrets?Catherine Carlisle is trapped in a loveless marriage and the threat of World War Two is looming. She sees no way out… that is until a trusted friend asks her to switch her husband’s papers in a desperate bid to confuse the Germans.Soon Catherine finds herself caught up in a deadly mixture of espionage and murder. Someone is selling secrets to the other side, and the evidence seems to point right at her.Can she clear her name before it’s too late?Readers Love THE SILENT WOMAN‘Intriguing and page-turning.’‘I really enjoyed this fascinating historical thriller.’‘an absorbing novel’‘a marvellous historical suspense that had me engrossed from the start.’‘I read it in just one sitting.’‘a seamless mix of historical fiction and mystery.’

Would you sell your secrets?

Catherine Carlisle is trapped in a loveless marriage and the threat of World War Two is looming. She sees no way out… that is until a trusted friend asks her to switch her husband’s papers in a desperate bid to confuse the Germans.

Soon Catherine finds herself caught up in a deadly mixture of espionage and murder. Someone is selling secrets to the other side, and the evidence seems to point right at her.

Can she clear her name before it’s too late?

The Silent Woman

Terry Lynn Thomas

ONE PLACE. MANY STORIES

Copyright (#ulink_894d9245-4e3d-519e-83a7-b837bf7e51c4)

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2018

Copyright © Terry Lynn Thomas 2018

Terry Lynn Thomas asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

E-book Edition © April 2018 ISBN: 9780008271596

TERRY LYNN THOMAS

TERRY LYNN THOMAS grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area, which explains her love of foggy beaches, windy dunes, and Gothic mysteries. When her husband promised to buy Terry a horse and the time to write if she moved to Mississippi with him, she jumped at the chance. Although she had written several novels and screenplays prior to 2006, after she relocated to the South she set out to write in earnest and has never looked back.

Now Terry Lynn writes the Sarah Bennett Mysteries, set on the California coast during the 1940s, which feature a misunderstood medium in love with a spy. Neptune’s Daughter is a recipient of the IndieBRAG Medallion. She also writes the Cat Carlisle Mysteries, set in Britain during World War II. The first book in this series, The Silent Woman, is out in April 2018. When she’s not writing, you can find Terry Lynn riding her horse, walking in the woods with her dogs, or visiting old cemeteries in search of story ideas.

For Doug, with all my love.

Contents

Cover (#uead17ab4-1078-57de-a48a-d517650a83e1)

Blurb (#ufc5b8be4-a74c-510e-8c2a-97da6436982e)

Title Page (#u9edde3bd-08df-59e9-a6bc-a87fb4e9b020)

Copyright (#ulink_fca5cd8c-a354-5084-9d4d-3b066cd76a89)

Author Bio (#ubc073058-4591-59dc-b675-b14d8841a7af)

Dedication (#ud982bae2-759d-5c31-b89e-bd210b602518)

Prologue (#ulink_96cf99f5-0617-5077-8e1a-726141792906)

Chapter One (#ulink_1567e153-da03-572d-835b-f96a110854d7)

Chapter Two (#ulink_7a13ea40-ac27-541b-8fab-593137c19610)

Chapter Three (#ulink_a54d7e62-8353-5454-a9b1-e589320a0908)

Chapter Four (#ulink_59e3dad3-5ccf-539a-a416-8df2bd899fad)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Endpages (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#ulink_d7557455-8ed5-5d7e-acb5-5c5460448395)

Berlin, May 1936

It rained the day the Gestapo came.

Dieter Reinsinger didn’t mind the rain. He liked the sound of the drops on the tight fabric of his umbrella as he walked from his office on Wilhelmstrasse to the flat he shared with his sister Leni and her husband Michael on Nollendorfstrasse. The trip took him the good part of an hour, but he walked to and from work every day, come rain or shine. He passed the familiar apartments and plazas, nodding at the familiar faces with a smile.

Dieter liked his routine. He passed Mrs Kleiman’s bakery, and longed for the pfannkuchen that used to tempt passers-by from the display window. He remembered Mrs Kleiman’s kind ways, as she would beckon him into the shop, where she would sit with him and share a plate of the jelly doughnuts and the strong coffee that she brewed especially to his liking. She was a kind woman, who had lost her husband and only son in the war.

In January the Reich took over the bakery, replacing gentle Mrs Kleiman with a ham-fisted fraulein with a surly attitude and no skill in the kitchen whatsoever. No use complaining over things that cannot be fixed, Dieter chided himself. He found he no longer had a taste for pfannkuchen.

By the time he turned onto his block, his sodden trouser legs clung to his calves. He didn’t care. He thought of the hot coffee he would have when he got home, followed by the vegetable soup that Leni had started that morning. Dieter ignored the changes taking place around him. If he just kept to himself, he could rationalise the gangs of soldiers that patrolled the streets, taking pleasure in the fear they induced. He could ignore the lack of fresh butter, soap, sugar, and coffee. He could ignore the clenching in his belly every time he saw the pictures of Adolf Hitler, which hung in every shop, home, café, and business in Berlin. If he could carry on as usual, Dieter could convince himself that things were just as they used to be.

He turned onto his block and stopped short when he saw the black Mercedes parked at the kerb in front of his apartment. The lobby door was open. The pavement around the apartment deserted. He knew this day would come – how could it not? He just didn’t know it would come so soon. The Mercedes was running, the windscreen wipers swooshing back and forth. Without thinking, Dieter shut his umbrella and tucked himself into the sheltered doorway of the apartment building across the street. He peered through the pale rain and bided his time. Soon he would be rid of Michael Blackwell. Soon he and Leni could get back to living their quiet life. Leni would thank him in the end. How could she not?

Dieter was a loyal German. He had enlisted in the Deutsches Heer – the Germany army – as an eighteen-year-old boy. He had fought in the trenches and had lived to tell about it. He came home a hardened man – grateful to still have his arms and legs attached – ready to settle down to a simple life. Dieter didn’t want a wife. He didn’t like women much. He didn’t care much for sex, and he had Leni to care for the house. All Dieter needed was a comfortable chair at the end of the day and food for his belly. He wanted nothing else.

Leni was five years younger than Dieter. She’d celebrated her fortieth birthday in March, but to Dieter she would always be a child. While Dieter was steadfast and hardworking, Leni was wild and flighty. When she was younger she had thought she would try to be a dancer, but quickly found that she lacked the required discipline. After dancing, she turned to painting and poured her passion into her work for a year. The walls of the flat were covered with canvases filled with splatters of vivid paint. She used her considerable charm to connive a showing at a small gallery, but her work wasn’t well received.

Leni claimed that no one understood her. She tossed her paintbrushes and supplies in the rubbish bin and moved on to writing. Writing was a good preoccupation for Leni. Now she called herself a writer, but rarely sat down to work. She had a desk tucked into one of the corners of the apartment, complete with a sterling fountain pen and inkwell, a gift from Dieter, who held a secret hope that his restless sister had found her calling.

Now Michael Blackwell commandeered the writing desk, the silver pen, and the damned inkwell. Just like he commandeered everything else.

For a long time, Leni kept her relationship with Michael Blackwell a secret. Dieter noticed small changes: the ink well in a different spot on Leni’s writing desk and the bottle of ink actually being used. The stack of linen writing paper depleted. Had Leni started writing in earnest? Something had infused her spirit with a new effervescence. Her cheeks had a new glow to them. Leni floated around the apartment. She hummed as she cooked. Dieter assumed that his sister – like him – had discovered passion in a vocation. She bought new dresses and took special care with her appearance. When Dieter asked how she had paid for them, she told him she had been economical with the housekeeping money.

For the first time ever, the household ran smoothly. Meals were produced on time, laundry was folded and put away, and the house sparkled. Dieter should have been suspicious. He wasn’t.

He discovered them in bed together on a beautiful September day when a client had cancelled an appointment and Dieter had decided to go home early. He looked forward to sitting in his chair in front of the window, while Leni brought him lunch and a stein filled with thick dark beer on a tray. These thoughts of home and hearth were in his mind when he let himself into the flat and heard the moan – soft as a heartbeat – coming from Leni’s room. Thinking that she had fallen and hurt herself, Dieter burst into the bedroom, only to discover his sister naked in the bed, her limbs entwined with the long muscular legs of Michael Blackwell.

‘Good God,’ Michael said as he rolled off Leni and covered them both under the eiderdown. Dieter hated Michael Blackwell then, hated the way he shielded his sister, as if Leni needed protection from her own brother. Dieter bit back the scream that threatened and with great effort forced himself to unfurl his hands, which he was surprised to discover had clenched into tight fists. He swallowed the anger, taking it back into his gut where it could fester.

Leni sat up, the golden sun from the window forming a halo around her body as she held the blanket over her breasts. ‘Dieter, darling,’ she giggled. ‘I’d like you to meet my husband.’ Dieter took the giggle as a taunting insult. It sent his mind spinning. For the first time in his life, he wanted to throttle his sister.

At least Michael Blackwell had the sense to look sheepish. ‘I’d shake your hand, but I’m afraid …’

‘We’ll explain everything,’ Leni said. ‘Let us get dressed. Michael said he’d treat us to a special dinner. We must celebrate!’

Dieter had turned on his heel and left the flat. He didn’t return until late that evening, expecting Leni to be alone, hurt, or even angry with him. He expected her to come running to the door when he let himself in and beg his forgiveness. But Leni wasn’t alone. She and Michael were waiting for Dieter, sitting on the couch. Leni pouted. Michael insisted the three of them talk it out and come to an understanding. ‘Your sister loves you, Dieter. Don’t make her choose between us.’

Michael took charge – as he was wont to do. Leni explained that she loved Michael, and that they had been seeing each other for months, right under Dieter’s nose. Dieter imagined the two of them, naked, loving each other, while he slaved at the office to put food on the table.

‘You could have told me, Leni,’ he said to his sister. ‘I’ve never kept anything from you.’

‘You would have forbidden me to see him,’ Leni said. She had taken Michael’s hand. ‘And I would have defied you.’

She was right. He would have forbidden the relationship. As for Leni’s defiance, Dieter could forgive his foolish sister that trespass. Michael Blackwell would pay the penance for Leni’s sins. After all, he was to blame for them.

Leni left them to discuss the situation man to man. Dieter found himself telling Michael about their parents’ deaths and the life he and Leni shared. Michael told Dieter that he was a journalist in England and was in Germany to research a book. So that’s where the ink and paper have been going, Dieter thought. When he realised that for the past few months Michael and Leni had been spending their days here, in the flat that he paid for, Dieter hated Michael Blackwell even more. But he didn’t show it.

Michael brought out a fine bottle of brandy. The two men stayed up all night, talking about their lives, plans for the future, and the ever-looming war. When the sun crept up in the morning sky, they stood and shook hands. Dieter decided he could pretend to like this man. He’d do it for Leni’s sake.

‘I love your sister, Dieter. I hope to be friends with you,’ Michael said.

Dieter wanted to slap him. Instead he forced a smile. ‘I’m happy for you.’

‘Do you mind if we stay here until we find a flat of our own?’

‘Of course. Why move? I’d be happy if you both would live here in the house. I’ll give you my bedroom. It’s bigger and has a better view. I’m never home anyway.’

Michael nodded. ‘I’d pay our share, of course. I’ll discuss it with Leni.’

Leni agreed to stay in the flat, happy that her new husband and her brother had become friends.

Months went by. The three of them fell into a routine. Each morning, Leni would make both men breakfast. They would sit together and share a meal, after which Dieter would leave for the office. Dieter had no idea what Michael Blackwell got up to during the day. Michael didn’t discuss his personal activities with Dieter. Dieter didn’t ask about them.

He spent more and more time in his room after dinner, leaving Leni and Michael in the living room of the flat. He told himself he didn’t care, until he noticed subtle changes taking place. They would talk in whispers, but when Dieter entered the room, they stopped speaking and stared at him with blank smiles on their faces.

It was about this time when Dieter noticed a change in his neighbours. They used to look at him and smile. Now they wouldn’t look him in the eye, and some had taken to crossing the street when he came near. They no longer stopped to ask after his health or discuss the utter lack of decent coffee or meat. His neighbours were afraid of him. Leni and Michael were up to something, or Michael was up to something and Leni was blindly following along.

During this time, Dieter noticed a man milling outside the flat when he left for his walk to the office. He recognised him, as he had been there the day before, standing in the doorway in the apartment building across the street. Fear clenched Dieter’s gut, cramping his bowels. He forced himself to breathe, to keep his eyes focused straight ahead and continue on as though nothing were amiss. He knew a Gestapo agent when he saw one. He heard the rumours of Hitler’s secret police. Dieter was a good German. He kept his eyes on the ground and his mouth shut.

Once he arrived at his office, he hurried up to his desk and peered out the window onto the street below. Nothing. So they weren’t following him. Of course they weren’t following him. Why would they? It didn’t take Dieter long to figure out that Michael Blackwell had aroused the Gestapo’s interest. He had to protect Leni. He vowed to find out what Michael was up to.

His opportunity came on a Saturday in April, when Leni and Michael had plans to be out for the day. They claimed they were going on a picnic, but Dieter was certain they were lying when he discovered the picnic hamper on the shelf in the kitchen. He wasn’t surprised. His sister was a liar now. It wasn’t her fault. He blamed Michael Blackwell. He had smiled and wished them a pleasant day. After that, he moved to the window and waited until they exited the apartment, arm in arm, and headed away on their outing. When they were safely out of sight, Dieter bolted the door and conducted a thorough, methodical search.

He went through all of the books in the flat, thumbing through them before putting them back exactly as he found them. Nothing. He rifled drawers, looked under mattresses, went through pockets. Still nothing. Desperate now, he removed everything from the wardrobe where Michael and Leni hung their clothes. Only after everything was removed did Dieter see the wooden crate on the floor, tucked into the back behind Michael’s tennis racket. He took it out and lifted the lid, to reveal neat stacks of brochures, the front of which depicted a castle and a charming German village. The cover read, Lernen Sie Das Schone Deutschland: Learn About Beautiful Germany. Puzzled, Dieter took one of the brochures, opened it, read the first sentence, and cried out.

Inside the brochure was a detailed narrative of the conditions under Hitler’s regime. The writer didn’t hold back. The brochure told of an alleged terror campaign of murder, mass arrests, execution, and an utter suspension of civil rights. There was a map of all the camps, which – at least according to this brochure – held over one hundred thousand or more Communists, Social Democrats, and trade unionists. The last page was a plea for help, a battle cry calling for Hitler and his entire regime to be overthrown.

Dieter’s hand shook. Fear made his mouth go dry. They would all be taken to the basement at Prinz Albrecht Strasse for interrogation and torture. If they survived, they would be sent to one of the camps. A bullet to the back of the head would be a mercy. Sweat broke out on Dieter’s face; drops of it formed between his shoulder blades. He swallowed the lump that formed in the back of his throat, as the fear morphed into blind, infuriating anger and exploded in a black cloud of rage directed at Michael Blackwell.

How dare he expose Leni to this type of danger? Dieter needed to protect his sister. He stuffed the brochures back in the crate, put the lid on it, and pushed the box back into the recesses of the wardrobe. There was only one thing for Dieter to do.

Chapter One (#ulink_cc5d714b-09fa-5d92-8e69-5f3659ac3119)

Marry in haste, repent at leisure, says the bird in the gilded cage. The words – an apt autobiography to be sure – ran round and round in Cat Carlisle’s head. She pressed her forehead against the cold windowpane and scanned the street in front of her house. Her eyes roamed the square, with its newly painted benches and gnarled old trees leafed out in verdant June splendour. A gang of school-aged boys kicked a ball on the grass, going out of their way to push and shove as they scurried along. They laughed with glee when the tallest of the group fell on his bum, turned a somersault, popped back up, and bowed deeply to his friends. She smiled and pushed away the longing that threatened whenever a child was near.

She thought of the time when she and her husband had loved each other, confided in each other. How long had it been since they’d had a civil conversation? Five years? Ten? How long had it been since she discovered that Benton Carlisle and Trudy Ashworth – of the Ashworth textile fortune – were involved in a long-term love affair? Ten years, two months and four days. For the record book, that’s how long it took for Benton’s love to morph into indifference and for the indifference to fester into acrimony. Now Cat and her husband rarely spoke. On the rare occasions when they did speak, the words between them were sharp and laced with animosity.

Cat turned and surveyed the room that she had claimed for her own, a small sanctuary in the Carlisles’ Kensington house. When she and Benton discovered she was with child the first time, they pulled down the gloomy wallpaper and washed the walls a charming shade of buttercup yellow, perfect for a child of any sex. But Cat had lost the child before the furniture had been ordered. In an abundance of caution, they hadn’t ordered furniture when Cat became pregnant for a second and third time. Those babies had not survived in her womb either. Now she had claimed the nursery as her own.

It was the sunniest room in the house. When Benton started to stay at his club – at least that’s what he told Cat; she knew he really stayed at Trudy’s flat in Belgravia – Cat moved in and decorated it to suit her own taste. She found she rather liked this small space. A tiny bed, an armoire to hold her clothes, and a writing table – with space between the pieces – were the only furnishings in the room. She had removed the dark Persian rug and left the oak floors bare, liking the way the honey-toned wood warmed the room. She had washed away the buttercup yellow and painted the walls stark white.

‘Miss?’ The maid stood in the open doorway of Cat’s bedroom. She was too young to be working, thirteen if she was a day, skinny and pale with a mousy brown bun peeking out from the white cap and sharp cheekbones that spoke of meals missed.

‘Who’re you?’ Cat asked. She forced a smile so as not to scare the poor thing.

‘Annie, ma’am.’ Annie took a tentative step into Cat’s room. In one hand she carried a wooden box full of feather dusters, rags, and other cleaning supplies. In the other she carried a broom and dustpan. ‘I’m to give you the message that Alicia Montrose is here. She is eager to see you.’ She looked around the room. ‘And then I am to turn your room.’

‘I’ll just finish up and be down shortly,’ Cat said.

The girl hesitated in the doorway.

‘You can come in and get started,’ Cat said.

‘Thank you, miss.’ The girl moved into the room and started to work away, focusing on the tasks at hand. ‘Do you mind if I open the window? I like to air the bed linens.’

‘Of course not,’ Cat said.

She reached for the box that held her hairpins and attempted to wrangle her curls into submission. Behind her, the child opened the window and pulled back the sheets on Cat’s bed. While the bed linens aired, Annie busied herself with the dusting and polishing.

Cat turned back to the mirror and wondered how she could avoid seeing Alicia Montrose. She couldn’t face her, not yet. The wounds, though old, were still raw.

The Montrose family had always been gracious and kind to her, especially in the beginning of her relationship with Benton when she felt like a fish out of water, among the well-heeled, tightly knit group who had known each other since childhood, and whose parents and grandparents before them had been close friends.

Many in Benton’s circle hadn’t been so quick to welcome Cat into their fold. Not the Montroses. They extended every courtesy towards Cat. Alicia took Cat under her wing and saw that she was included in the events the wives scheduled when the husbands went on their hunting and fishing trips. Alicia also sought Cat out for days of shopping and attending the museum. And when the Bradbury-Scots invited Cat and Benton for dinner, Alicia swept in and tactfully explained the myriad of customs involved.

‘They’ll be watching you, Cat. If you hold your teacup incorrectly, they’ll never let you live it down. And Lady Bradbury-Scott will load the table with an excess of forks and knives just to trip you up.’ Alicia had taken Cat to her home every day for a week, where they dined on course after course of delicious food prepared by the Montroses’ cook. While they ate, Alicia explained every nuance to Cat – speak to the guest on the right during the first course. Only when that is finished can you turn to the left. The rules were legion.

Cat credited Alicia’s tutelage for her success at the dinner. She had triumphed. The Bradbury-Scotts accepted her, so did Benton’s friends, all thanks to Alicia Montrose. One of these days Cat would need to make peace with Alicia, and talk to her about why she had resisted Alicia’s overtures. Cat didn’t expect Alicia to forgive her. How could she? But at least Alicia could be made to understand what motivated Cat to behave so shabbily. But not today.

She plunked her new green velvet hat on her head and pinned it fast without checking herself in the mirror. As she tiptoed downstairs, she wondered if she could sneak out the kitchen door and avoid the women altogether. With any luck, she could slip out unnoticed and avoid the litany of questions and criticisms that had become Isobel’s standard fare over the years.

‘I think the chairs should be in a half circle around this half of the room.’ Alicia’s voice floated up the stairs. ‘A half circle is so much more welcoming, don’t you agree?’

‘Oh, I agree.’ Isobel Carlisle, Cat’s domineering sister-in-law, a shrewish woman who made a career of haranguing Cat, spoke in the unctuous tone reserved for Alicia alone. ‘Move them back, Marie.’

Poor Marie. Isobel’s secretary bore the brunt of Isobel’s self-importance. Cat didn’t know how she stood it, but Marie Quimby had been Isobel’s loyal servant for years. Cat slunk down the stairs like a thief in her own home.

‘But we just had them in the half circle, and neither of you liked that arrangement,’ Marie said. She sounded beleaguered and it was only nine in the morning.

‘There you are, Catherine. Bit late this morning.’ Isobel stepped into the hallway.’

Catherine,’ Alicia said. She smiled as she air-kissed Cat’s cheek, while Isobel looked down her nose in disapproval. ‘How’ve you been, Cat? You’re looking well. We were worried about you. Good to see you’ve got the roses back in your cheeks.’ Alicia was resplendent in a navy dress and a perfect hat.

‘It was just a bout of influenza. I am fully recovered,’ Cat said. ‘And thank you for the lovely flowers and the card.’

‘Won’t you consider helping us? We could certainly use you. No one has a knack for getting people to part with their money like you do.’

Cat smiled, ignoring Isobel’s dagger-like glare. ‘Maybe next time. How’re the boys?’

‘Growing like mad. Hungry all the time. They’re excited about our trip to Scotland. The invitation’s open, if you’d like to join?’ Alicia let the question hang in the air between them.

‘I’ll think about it.’ Cat backed out of the room, eager to be outside. ‘It’s good to see you, Alicia.’

‘Come to the house for the weekend, Cat. If the boys are too much, I’ll send them to their gran’s house. We’ve some catching up to do.’

‘I’d like that,’ Cat said. ‘Must run.’

‘Perhaps we should get back to work?’ Isobel said.

A flash of sadness washed over Alicia’s face. ‘Please ring me, Catherine. At least we can have lunch.’

‘I will. Promise,’ Cat said.

‘Isobel, I’ll leave you to deal with the chairs. I’m going to use your telephone and call the florist.’

‘Of course,’ Isobel said.

Once Alicia stepped away, Isobel stepped close to Cat and spoke in a low voice. ‘I do not appreciate you being so forward. You practically threw yourself at Alicia. Don’t you realise what my association on this project could do for me, for our family, socially? This is very important, Catherine. Don’t force me to speak to Benton about your behaviour. I will if I have to.’

Cat ignored her sister-in-law, as she had done a million times before. She walked past the drawing room, where Marie was busy arranging the chairs – heavy wooden things with curvy legs and high backs. Marie looked up at Cat and gave her a wan smile.

Isobel, stout and strong with a mass of iron-grey waves, was the exact opposite of Marie, who was thin as a cadaver and obedient as a well-trained hound. Marie’s wispy grey hair stood in a frizzy puff on her head, like a mangled halo. Cat didn’t understand the relationship between the women. Isobel claimed that her volunteer work kept her so busy that she needed an assistant to make her appointments and type her letters. Cat didn’t believe that for one minute. Cat knew the true reason for Marie’s employment. Isobel needed someone to boss around.

Her sister-in-law surveyed Cat’s ensemble from head to toe, looking for fault. Cat dismissed her scrutiny. After fifteen years of living in the Carlisle house, she had become a master at disregarding Isobel.

‘What is it, Isobel? I really must go,’ Cat said.

‘Before you go, I’d like you to touch up the silver. And maybe you could give Marie a hand in the kitchen? I know it’s a bit of an imposition, but the agency didn’t have a cook available today. I’m expecting ten committee members for our meeting this afternoon. I wouldn’t want to run out of food. I need these committee members well fed. We’ve much work to do.’

‘I can manage, Izzy,’ Marie said.

‘I’ve asked Catherine,’ Isobel said. ‘And those chairs won’t move themselves.’

‘I’m going out.’ Cat paused before the mirror. She fixed her hat and fussed with her hair, taking her time as she drew the delicate veil over her eyes.

‘You should be grateful, Catherine. Benton has given you a home and a position in society. You’ve made it clear you’re not happy here, but a little gratitude wouldn’t go amiss. You and Benton may be at odds, but that doesn’t change things. You’d be on the street if it weren’t for us. You’ve no training. It’s not like you are capable of earning your living.’

‘I hardly think any gratitude I feel towards my husband should be used to benefit you. I’m not your servant, Isobel. I’m Benton’s wife. You seem to have forgotten that.’

Isobel stepped so close to Cat that their noses almost touched. When she spoke, spittle flew, but Cat didn’t flinch. She didn’t back away when Isobel said, ‘I suggest you take care in your dealings with me, Catherine. I could ruin you.’

Cat met Isobel’s gaze and didn’t look away. ‘Do your best. I am not afraid of you.’ She stepped away and forced a smile. ‘Silly old cow,’ Cat whispered.

‘What did you call me?’

‘You heard me.’ Cat picked up her handbag. ‘I don’t know when I’ll be back. Have a pleasant day.’ She turned her back on Isobel and stepped out into the summer morning.

She headed out into the street and took one last glance at the gleaming white house, one of many in a row. Benton’s cousin, Michael Blackwell, Blackie for short, stood in the window of Benton’s study, bleary-eyed from a night of solitary drinking in his room. Blackie spent a lot of time in Benton’s study, especially when Benton wasn’t home. She knew why – that’s where the good brandy was kept.

Blackie had escaped Germany with his life, the clothes on his back, and nothing else. A long-lost cousin of Benton and Isobel, Blackie turned up on their doorstep, damaged from the narrow escape and desperate for a place to live. Of course they had taken him in. The Carlisles were big on family loyalty. Now Blackie worked at a camera shop during the day and spent his nights sequestered in his room with a bottle of brandy and his memories of Hitler.

Cat often wondered what happened in Germany to frighten Blackie so, but she didn’t have the heart to make him relive his suffering just to satisfy her curiosity. He saw Cat, smiled at her, and held up a snifter of Benton’s brandy, never mind that it was only half past nine in the morning. Everyone knew Blackie drank to excess. They didn’t care. He was family. Cat waved at him, anxious to get as far away from the Carlisle house as fast as she could.

***

Thomas Charles watched the watcher, sure now that the woman who had been lurking outside the Carlisle house for the past week was Marlena Helmschmidt, aka Marlena Barrington, most notably known as Marlena X. He thought back to the last time he and Marlena had been face to face. He thought of her husband, dead from a bullet. He thought of Gwen, his colleague at the time, huddled against a wall, a knife in her chest, clinging to life, and ultimately losing the battle.

Marlena X specialised in espionage. She was an extremely competent typist and secretary. She spoke French, German, English, and Swahili. It was rumoured that she could take shorthand just as fast as someone could speak. The last time he had dealt with Marlena, she had insinuated herself into a high-clearance position working for the navy. God knows what information she had accessed. Her bosses sang her praises.

When Thomas told them their darling was a spy, they shunned him, dismissed his accusations, and sent him on his way. Until documents went missing, and they came crawling back. Thomas never said I told you. That was most certainly not his style. Marlena was tough. She had the personal qualities of a well-educated sophisticate, but underneath the polished veneer, was a woman who knew her way around bombs and could street fight as well as any man. Her lithe and supple frame allowed her break into the most challenging locations. She also had a quick hand with locks.

Her appearance at the Carlisles’ was not a portent of good things. What the devil was she up to? He stepped close to the oak tree in the garden square, keeping himself hidden, as Marlena arrived to sit on the bench, just as she had done every day for the past week. His orders were clear – watch her; do not approach her. Find out where she is staying, who she talks to, anything about her day-to-day activities, and report back.

He’d been watching her for a week now. Her routine never varied: arrive at the Carlisle house and sit on the usual bench, the one that afforded the best view of the house, one of a neat row that had its own garden square.

Thomas had wanted to approach her, finish the business between them, but he knew better than to let his personal feelings interfere with his work. He sunk further out of sight and watched. Marlena reached into the large bag that sat next to her and took out a ball of yarn and knitting needles. She started to knit, her hands industrious as they wove the yarn over the needles.

Soon a girl in a maid’s uniform came out with a bucket of hot steaming water. She spent a good fifteen minutes scrubbing the front steps and polishing the brass plate on the front door. She made quick work of it and did a thorough job. Thomas watched as the girl went down the steps and stared up at the front door from the vantage point of the pavement, scrub brush in hand, surveying her work. She nodded, picked up her bucket and went back into the house. Still the woman sat on the bench.

At nine a.m. a long black saloon crept to the kerb. A burly chauffeur hurried around to the back of the car, surprisingly nimble for a man so large. Thomas noticed the driver’s meaty hands and the way his eyes roamed the area as he held the door for Mr Carlisle. Thomas had been briefed on Mr Carlisle’s firm and the work they were doing for the Air Ministry: something to do with detecting enemy aircraft, technology that would help England win the inevitable war. The chauffeur was more than just a driver.

After the car pulled away, the woman checked her watch, took out a tiny notebook, and wrote something in it. Yesterday she abandoned the bench after Mr Carlisle’s car pulled away. Not today. Another car came, a taxi this time, and an attractive blonde dressed in a navy blue suit alighted and went up to the front door. The woman on the bench didn’t even look up.

She’s planning something, Thomas thought. And it has to do with Mr Carlisle’s work for the Air Ministry.

Soon the redhead – Mr Carlisle’s wife, according to the dossier – came out of the house, just as she had done yesterday. Thomas watched as she pulled the door behind her and walked down the nine steps to the street. Even from a distance Thomas could tell that Mrs Carlisle was a beautiful woman: tall, slender, and with a mass of red hair. She moved like a dancer. Today she wore a green suit with a matching hat, a tiny thing with a sheer veil that covered her eyes. She stopped outside the front door and pretended to fiddle with the clasp of her handbag while she studied her surroundings, as if looking for someone.

Thomas stepped back behind the tree so he could watch Marlena X. If the German agent followed Mrs Carlisle, he would follow as well. The bench was empty. Marlena X was gone.

Damn.

Mrs Carlisle turned right and headed towards the high street, where Thomas knew she would enter the garden square, just as she did every day. Thomas followed, staying far behind so as not to draw attention to himself. He nearly missed Marlena X, who seemed to appear out of nowhere as she followed the redhead, keeping a safe distance between them, taking her time. Thomas tailed them both. Marlena kept the perfect distance from Mrs Carlisle so as not to arouse suspicion. Marlena knew her job.

Mrs Carlisle stopped at the gate to the entrance of the square. She pushed the veil up and tipped her face to the sun, as though she were making a wish or an offering of some sort. The angle of her face gave Thomas a clear view of her profile. He took in the well-shaped nose, the perfect cheekbones. He couldn’t help but notice the full lips and the woman’s long white throat. He wondered – once again – what she was up to, only to realise too late that he had been so focused on Mrs Carlisle he had once again lost sight of Marlena X. Never mind. She’s here. I can feel her.

***

The sun warmed Cat’s back as she walked, her tension easing with each step that led her away from the house. Benton would be furious if he knew what Cat was up to. He had wealth untold, but he was stingy with Cat’s pocket money. On more than one occasion over the years Cat had approached her husband about getting a job, but he forbade her. ‘A man in my position cannot have a wife who works.’

At one point, Cat volunteered at the hospital. She spent her day doing mindless things like arranging flowers, sorting books, and delivering magazines to the patients. The work hadn’t been challenging, but it gave her something to do and an excuse to get away from the house.

She came to a standstill as she stepped through the gates of the wooded garden square that had become her private sanctuary, a place to escape Isobel’s prying eyes and Alicia Montrose’s relentless pursuit to rekindle their friendship. She stood in the sunlight for a moment and tipped her head back, not caring that the sun would cause her skin to freckle. She said a silent prayer, I want to live my own life, be independent. How do I do this? Give me a sign.

She saw Reginald just as she stepped onto the sunny green in the middle of the garden square. The old man smiled and waved a hand at her. They had first met at this very spot on a spring day in 1932, when Reginald approached Cat out of the blue and said that he had known her father during the war. Over the next five years they bonded while cajoling the squirrels to take the food out of their hands. Reginald regaled Cat with stories of her father – a cryptographer, who worked for MI5 and served valiantly – and Cat’s mother.

Cat savoured those conversations about her parents, who died tragically in a motorcar accident in 1917 when her father was on leave. Now she considered Reginald a trusted friend, a small thread to a tapestry that didn’t involve her husband and sister-in-law.

For some reason, today Cat noticed the hand that grasped the walking stick had grown more gnarled, the hump between the shoulder blades more defined. Sir Reginald’s eyes hadn’t changed a bit, cornflower blue with a penetrating gaze that missed nothing. But his body had aged.

‘What’s wrong? You’re wound tight as a spring,’ Reginald said.

‘I’m a thirty-seven-year-old woman who cannot have children, lives in a loveless marriage, and sees no escape.’

‘Catherine –’

‘Sorry. I didn’t come here to discuss my problems. How are you? Lovely day.’

‘Can you not leave? Surely your aunt and uncle will help?’

‘I need to sort this out on my own.’ She didn’t give voice to her true feelings: I am terrified to leave him. What am I, if I’m not his wife? She put on a brave face and turned to face Reginald. Out of the corner of her eye she saw a woman on a blanket, her child in her lap. Near her, two blonde-haired girls chased each other, their dollies sitting on the blanket.

‘I’m grateful to you, Reginald. The work has been a great help, but I’d feel better if you told me what I was delivering and why everything is so secretive. Am I in danger?’

‘No danger that I know of,’ Reginald said. ‘I’m sorry. You’re going to have to trust me. Just know that you’re helping in ways that you will never understand. Keep your eyes open. If you need to reach me, just follow the instructions, call the numberand use the code word.’

‘St Edmund’s pippins,’ Cat said.

‘Just use it in a sentence. I’ll be there.’

‘All this cloak-and-dagger intrigue is affecting my judgement.’

Reginald rifled through the briefcase that rested on the bench between them. He pulled out an envelope and handed it to Cat. ‘This needs to be delivered today. Hamer, Codrington, and Blythe again – same address as last week. The secretary will let you in and excuse himself, claiming an important meeting. You’re to go to the same office and insert the envelope on the top shelf, just like last time. There’s nothing to pick up today.’

‘Will they let me in the door today?’ Desperate for income of her own, Cat had accepted Reginald’s offer of easy employment – delivering packages and on occasion accepting something to return to him – without question. The work was easy, the money a boon. The Carlisle name allowed Cat access to the finest dressmakers, spas, hairdressers – any luxury she could imagine – but other than a small allowance she received from her parents’ estate, Cat had no money of her own. She hated being dependent on Benton, especially since he was so stingy. Her work with Reginald remedied that. The money – which she saved in an envelope hidden in her room – provided the promise of freedom.

The courier work had been easy enough, and Cat hadn’t experienced any difficulties, until last week. Her instructions had been to deliver a similar innocuous-looking envelope to the firm of Hamer, Codrington, and Blythe. By prearrangement, Cat would be let in the building and left on her own. She was to walk down a hallway to an empty office and deposit the envelope on the top shelf of an out-of-the-way bookcase.

Instead of being given entrance to the building, a new secretary – a supercilious young man who needed to be slapped – had ushered her out into the street and had asked her question after question, interrogating Cat and growing more and more suspicious when she refused to answer his questions. He wouldn’t even let her into the office. Luckily, after fifteen harrowing minutes, Mr Codrington’s secretary had intervened on her behalf and brought her into the building. As planned, he excused himself, leaving Cat to carry out her assignment.

‘They’re expecting you. There won’t be any trouble this time.’ He pulled out another envelope, this one smaller and full of notes. ‘This is for you. You did well last time. Codrington’s secretary told us that you handled the situation like a professional. There’s extra in there for your efforts.’

‘Thank you,’ Cat said. She tucked the money in her handbag.

‘Your father would be proud of you, Catherine. Never forget that. You’re doing a patriotic service for your King and country. Caution is the operative word, my dear. I’ll have something else for you in a few days. Look for my ad.’ Reginald stood, his arthritic knees popping from the effort. ‘Not as young as I used to be. I’ll do anything I can to help you get sorted, Catherine. I mean that. Not all women are destined to do what society expects of them. I’m sorry that you and Benton weren’t blessed with children, but that’s not your fault, my dear. And there’s certainly no shame in it.’ He touched a gentle hand to her shoulder.

‘I know. Thank you for that.’

She sat on the bench in the warm summer sun and watched Reginald walk away. He was keeping something from her. Every fibre of her being sang with that truth. She wondered where he went when he wasn’t meeting with her. He told her over and over again – more so during the past six months or so – that another war was coming. Hitler was rearming, while France and England were sitting by, doing nothing.

Cat wondered why there was no mention of war in the newspapers. She’d never been interested in politics until she met Reginald. Now she scoured the newspapers, looking for any hint of the things Reginald told her about during their meetings in the park. Cat had been too young to do anything important in the last war, and it had resolved by the time she could make some contribution. But she had seen the soldiers coming home from the battlefield with their arms and legs blown off. She had seen the women who had lost husbands and sons and soon came to recognise that look of sorrow and emptiness.

Cat had arrived in London as a seventeen-year-old country girl, with a northern accent and all the wrong clothes. In the beginning, she tried to embrace her new life. Moving from a small village in Cumberland to London required a bit of adjustment. Lydia took her shopping for the latest fashions and dragged her along to art openings, plays, and writers’ salons. Cat tried to fit in. Aunt Lydia went out of her way to help Cat find a set of like-minded friends, but the death of her parents had ripped a hole in her heart. Cat preferred spending time alone with her grief.

And that was why – Cat realised from the Olympian vantage point of one who looks at the past with a critical eye – she married Benton at twenty-two, when she was young and naive and thought that the passion he stirred in her was the type of love that would withstand time, the type of love her parents shared. Cat knew now that her judgement about Benton – and about love in general – was gravely flawed.

She shook her head, chastising herself for her sentimentality. This was not the time for wistful dreams of days gone by. Full of purpose, Cat set off at a brisk pace, her heels clicking in time to the beat of the city. She blended in with the foot traffic, savouring the feeling that she was part of something bigger than herself, that she was doing something productive. Every now and again Reginald’s words would pop into her head. Not all women are destined to do what society expects of them. She certainly hadn’t disappointed on that score.

As she walked, her thoughts turned – as they often did of late – to her relationship with Alicia Montrose. Cat and Alicia became friends the minute they laid eyes on each other. Benton’s work schedule allowed Cat plenty of freedom. He approved of Cat’s friendship with the influential Montroses, and didn’t seem to care when they went on holidays to the sea, skiing in Switzerland, and to Alicia’s country house. Sometimes they would travel in a large group of women – Alicia Montrose had a large circle of friends – sometimes Cat and Alicia would travel alone.

The women were overjoyed when they became pregnant at the same time. But Cat had lost her child, while Alicia had given birth to a healthy boy. Reeling from the loss, Cat had slowly stepped away from society in general. She lost her desire to travel. She had no interest in anything. Over the next three years Alicia gave birth to two more children, while Cat suffered three more miscarriages.

Now the sight of Alicia Montrose caused an unbearable ache in Cat. She felt guilty for it. She knew that she had turned her back on a good friend. But she simply couldn’t face Alicia and her children, and the painful reminder of how things could have turned out for Benton and her.

Time changes friendships. Alicia was busy with her children. Cat involved herself in the fundraising work and charity balls that were the centre of her sister-in-law’s life. She found she had a knack for it, so she threw herself in, using the exhausting work as a psychological crutch. She and Alicia crossed paths and were polite to each other, but the sister-ness between them – a word coined by Alicia – had left. Cat lived a whirlwind of committee meetings and fundraisers, which she managed and oversaw with great success. The charity balls she organised grew exponentially each year. She was creative and hired lavish entertainment.

She worked herself to exhaustion, and would have continued to do so until a bout of influenza almost killed her. She had been in hospital for a month, and then at a luxurious spa for a rest cure for three months after that. During this time, Cat had re-examined the choices she made and had found herself wanting.

During Cat’s hospitalisation Alicia had visited her regularly. When Cat requested the nurses turn Alicia away, Alicia sent flowers and books. To this day, Alicia – with the tact and social grace that was her birthright – still made an effort. She had proven to be a true friend, and Cat had shunned her for her efforts.

She walked amid a throng of people, past the tobacco shop, a tea shop, and a dress shop. The woman who ran the haberdasher’s stood outside, surveying the street as though it were her personal domain, a faraway look in her eyes. Cat nodded to her as she walked past.

She needed to make things right with Alicia, but she had no idea how to go about doing so. The foot traffic diminished as Cat approached the block that housed Hamer, Codrington, and Blythe. She passed an insurance office and a watch and clock repair shop. What if she could just start over, someplace where no one knew her? She could adopt a child … She almost snorted with laughter. What would she do with a child? How could she possibly cope with a child by herself, with no job? She was snapped out of her reverie when someone grabbed the strap of her bag and yanked hard.

Cat cried out as pain wrenched her arm and raced up to her shoulder, like electricity travelling up a wire. The force stopped her and yanked her around, forcing her to come face to face with what at first glance appeared to be a small boy. On closer inspection Cat saw that her assailant was a woman, lithe and spry as a dancer, and very strong despite her size. The woman had clear skin, devoid of any cosmetics, brown eyes, and a thin mouth pursed in a line of determination.

‘Let go of my purse!’ Cat cried out.

The woman yanked on the bag. When that didn’t work, she reached inside, her fingers grasping Reginald’s envelope. Cat pulled her bag close to her chest and held fast. Her attacker persisted, but Cat held on.

‘Give it to me,’ the woman said.

‘Let go of me,’ Cat said.

‘You there!’ a man called out from down the street. He took off at a run towards Cat and her assailant, his tie flapping in the wind.

‘Just give me the envelope and you won’t get hurt,’ the woman said through gritted teeth.

With one final pull, Cat jerked the bag free of the woman’s grasp. The woman growled like a dog. The punch came hard and fast, like the strike of a snake. The woman’s fist connected with Cat’s cheek, knocking Cat’s head back. Stars swam before her. Her knees started to buckle. She clung to the bag as she sank to the hard pavement. Once she was down on the ground, she sat dazed and unable to move. Through the crowd of legs that stood around her, she recognised the scuffed brown shoes that belonged to the woman as she walked away, her gait sure and steady.

‘Call the police,’ someone said.

‘Is anyone a doctor? I think she’s in shock. That boy tried to steal her purse!’

The pavement seemed to roll like the deck of a ship.

‘Maybe we should move her,’ another voice said.

Cat’s vision blurred. Blood pulsed into the skin near her cheekbone and her eye. Fluid pushed its way into new places, causing the skin to tighten with swelling. How will I explain this to Benton? Cat thought.

‘Move aside. Move aside, please,’ Cat heard a man’s voice say. ‘I saw everything from down the road. Move, please, and let me get to her.’ The crowd parted and the man squatted near Cat and studied her face. He was very tall, with dark hair worn a bit longer than was fashionable. The strong line of his jaw was covered with the dark stubble of a beard. His intelligent grey eyes peered at Cat. Are you all right?’

‘Not sure,’ Cat said.

‘What is your name?’

‘Catherine.’

‘Do you know what year it is?’

‘It’s 1937. I’m not concussed,’ Cat said. ‘I’ve just been attacked.’

‘Can you stand?’ The man stood and held out his hand. ‘Take my hand, and I’ll help you up. Careful now. If you’re dizzy, just lean on me.’ She took his hand, and he pulled her to her feet. The man turned to the crowd. ‘All is well now. Carry on.’

Cat allowed the man to lead her to a bench in the shade. He helped her sit down before he went into the closest shop and returned with a glass of water.

‘Drink this. It will soothe you.’

Cat obeyed, letting the cool water run down her throat. While she drank, she noticed the man glance up and down the street.

‘I dare say she won’t come back.’ He studied Cat’s face. ‘I’m afraid you’re going to have a black eye. Do you want me to take you to hospital? Maybe you should have that seen to.’

‘I’m fine,’ Cat said. She brushed off her skirt, dismayed to see the large rip at the elbow of her new suit. Her hat had come off and now rested in the street. Cat watched, helpless, as a lorry drove over it, mashing it beyond repair.

‘May I escort you home or at least arrange for someone to come and get you?’

‘No, thank you. I’m fine really. I need to run an errand and then I’ll see myself home.’ She forced herself to sound strong and sure. ‘You’ve been very kind. I’ve an appointment just down the street. I know I must look a fright, but I’m all right, really. When I’m finished, I’ll go and have a cup of tea to settle my nerves.’

‘We really should call the police,’ the man said.

‘I’ll go directly there and make a report in person,’ Cat lied. She had no intention of going to the police.

‘Here’s my card. You’ll give that to the police? Have them call me. I got a pretty good look at her.’ He reached into the pocket of his suit and handed Cat a card printed on thick milky paper. Thomas Charles, Historian. There wasn’t an address, just a telephone exchange. She thanked him, took the card, and said her goodbyes, setting out once again to fulfil her obligation to Reginald. With each step, the anger that had saved her – and prevented the theft of Reginald’s documents – was replaced by a relentless knot of fear.

Fifteen minutes later she dropped off the envelope in the appropriate place. The secretary met her directly and – according to plan – excused himself and left Cat to her own devices. She was in and out of the building in less than five minutes. She resisted the urge to buy a new hat to replace the one that was damaged and turned her attention to more important matters, such as how she was going to explain her bruises to her inquiring sister-in-law and insolent husband.

***

Thomas took a taxi to an antiquarian bookshop in Piccadilly, lodged between a tailor and an estate agent. A rack of old books stood in front of the shop. A man browsed through the titles now, his hat pulled low over his head. As a precaution, Thomas walked past the estate agent and circled back. When he returned, the man was gone. He stepped into the shop and breathed in the smell of the old books.

He loved writing almost as much as he loved reading and books in general. He travelled Germany under the guise of being a writer, a cover that allowed him to move around without question. On a whim, Thomas decided that he would write a compendium on historical churches, a travel guide of sorts, in order to lend credence to his cover story. Thomas actually started the process of writing, jotting down a few paragraphs about the churches and sights he visited. The enjoyment he took from the process surprised and delighted him.

When he submitted the book to a publisher, who snapped it up in exchange for a hefty fee, Thomas was surprised. He studied craft, read how-to-write books, and even took a correspondence course in writing professionally. His career flourished. His books were met with critical acclaim.

The shop’s purveyor looked up from behind a desk and nodded, while Thomas continued to browse along the rows of the old books with their cracked leather spines and unique mustiness. He picked up a fine first edition of Ivanhoe when the bell jangled and Sir Reginald came in. Thomas tucked the book back on the shelf as the old man turned the closed sign to face the street and locked the front door. The proprietor nodded at Reginald and headed up a rickety flight of stairs at the back of the shop. Neither Reginald nor Thomas spoke until a door at the top of the stairs shut and footsteps creaked above them.

‘Were my suspicions correct then?’ Sir Reginald asked.

‘It’s Marlena X,’ Thomas said. ‘She’s been watching the house for the past week.’

‘Someone in that house is working with her,’ Reginald said.

‘Agreed.’

‘But you’ve never seen her make contact with anyone?’

‘No, sir,’ Thomas said.

‘And Mrs Carlisle?’

Thomas turned to face Reginald. ‘Marlena made a run for the papers she was carrying, just as you expected.’

Reginald took a deep breath. ‘And?’

‘Mrs Carlisle managed to thwart her by sheer willpower. She clung to that purse as though it were a lifeline. Marlena hit her. Mrs Carlisle fell to the ground, nearly passed out, but clutched at that damn purse.’ Thomas looked at Reginald. ‘I hope you know what you’re doing, putting an untrained woman such as Mrs Carlisle out in the field against the likes of Marlena X.’

‘I’m taking a risk, I know,’ Sir Reginald said, ‘but I’ll stand by it. Finish your report.’

‘I made contact with Mrs Carlisle, gave her my business card.’ Sir Reginald faced him, staring at him with that penetrating gaze that had brought many a man to his knees. ‘As far as she’s concerned, she’d been mugged. A crowd had gathered around her. I had to get close to confirm the documents were safe.’

‘Understood,’ Reginald said. ‘Watch her. See that she doesn’t come to harm.’

‘What about Marlena X?’

‘Leave her be for now. Let’s give her a nice long rope, shall we?’ He stared at Thomas. ‘Is this too personal for you? This is not time for vengeance. Gwen’s death was a tragedy, but you must not let it sway you. Not now. Too much is at stake.’

‘No, sir,’ Thomas lied. He knew full well what was at stake. But he had a score to settle with Marlena X, and he intended to do so, with or without Sir Reginald’s approval.

Sir Reginald unlocked the door, turned the sign back around to open, and without a backward glance, stepped out into the June afternoon.

Chapter Two (#ulink_bf84080a-fcab-570a-b092-df01d2f247bc)

One week had passed since Annie Havers had run away from her mother and lied her way into a service job in the posh Carlisle home. Timid Annie Havers had faced Isobel Carlisle and had told her that she was an orphan who needed a job. The minute she spoke the words, she expected the heavens to open and lightning to strike as punishment for her falsehood. At the very least, Annie expected Miss Carlisle to laugh in her face and send her back to Bermondsey.

But Miss Isobel Carlisle had not laughed in Annie’s face. Instead she stared down her long nose and asked a handful of questions relevant to housekeeping. Did Annie know how to dust? How would she go about cleaning a room? Could she cook a bit?

Annie answered all the questions truthfully. She knew how to keep house. She’d been helping her mum for as long as she could remember. She enjoyed it. She appreciated the satisfaction of a job well done. She didn’t tell Miss Isobel that the best part of domestic work was that it gave Annie time to paint pictures with her mind. She didn’t tell Miss Isobel that while she swung the broom back and forth, she imagined the brushwork necessary to capture the crashing waves of a seascape or that she could figure out which colours to mix to develop a shade of deep red as rich as blood. But this was the Carlisle house, and Miss Isobel Carlisle was looking for more than an uneducated girl. ‘Can you read?’

‘Yes, ma’am,’ Annie said. ‘I can do sums as well. I am – was – a good student, ma’am. I also draw. My dad was going to let me go to art school.’ Annie looked out the window. She could tell a partial form of the truth about this part of her life, for her father was indeed dead, and he had promised art school before the accident that had taken his life. ‘But he and my mum died. There was no place for me to go, and now I need a job.’

Miss Carlisle stared at Annie, judging her. Annie met her eyes and smiled. ‘I’m a good worker, ma’am.’

Miss Carlisle nodded her head and crossed her arms over her stout bosom. ‘I usually wouldn’t ask a girl with no experience about cooking, but our cook is taking care of her husband who has been ill. I’m looking for a temporary replacement, but have yet to find one. It’s usually just me, Marie, and Mrs Carlisle. We dine properly when my brother is home, which isn’t very often. He has a very important job that takes him out of town on a regular basis.’

Annie waited, not quite sure what to say.

‘Very well. You can start today. Marie will see you’re situated.’

The tall woman who sat next to Miss Carlisle during the interview stood up. She hadn’t spoken since she ushered Annie into the room, and Annie had all but forgotten she was even there. Now she noticed the crown of downy white frizz and the cadaverous frame. The woman’s clothes were rumpled, the hem of the skirt uneven. The white blouse she wore under the navy cardigan had a tiny stain on it. When Miss Marie smiled at Annie, a genuine smile that lighted her whole face, Annie liked her right away.

Unable to believe that she had gotten away with all the lies, Annie grabbed the valise she stole from her mother and hurried after the woman. She felt guilty about taking something so dear from her mum, but Annie couldn’t run away with her possessions in a paper bag. She vowed to repay her mother once she established herself. The bag now carried all of her worldly goods: a tattered copy of Through the Looking Glass, a picture of her grandparents, her good dress, her Sunday shoes, her nightgown and underclothes. She’d left her good winter coat at Harold Green’s house, but now at least she would have enough money to buy one before the summer weather turned.

The woman didn’t speak as Annie followed her to the back of the house and up a narrow staircase off the kitchen. Annie’s room was on the second floor, tucked into an out-of-the-way corner. The woman opened it, allowing Annie to step in first.

‘Welcome to the Carlisle house, Annie. I hope you’ll be happy here.’

The room was small and bright. A wooden bedstead was tucked in the corner, its crisp white linens frayed at the edges. On the opposite wall was a washstand, with a floral print pitcher and basin. Next to it lay a stack of flannels. The window was covered in muslin curtains embroidered in scarlet poppies and blue forget-me-nots.

For a moment Annie missed her real room, the room that she lived in before her father died and before her mum married Harold Green. That room was big, with well-worn rugs and large windows that flooded the room with light. At night, Annie would crawl into the high canopy bed that belonged to her gran, snuggle under the eiderdown, and fall asleep without a care in the world.

One corner of the room held her easel, a box full of paints, and a set of real mink brushes. She spent hours painting. When she wasn’t pretending to be an artist, she spent her free time playing in the garden with the children from the neighbourhood. She longed for the life that had been so cruelly taken away from her. When her dad died, the house they lived in had gone to her uncle. He had his own family to support, and although he offered Annie and her mum a room for as long as they wanted to stay there, Annie’s mum moved into a house that she couldn’t afford. To save themselves from poverty, Annie’s mum had married, and now here Annie was.

‘It’s all right, my dear. Things will be fine,’ Miss Marie said, as if she read Annie’s thoughts. ‘It’s been a little difficult since cook left. Her husband had a heart attack and she’s tending to him. The agency has been sending over replacements, but Isobel has yet to find one that’s satisfactory. With Benton – that’s Mr Carlisle – working so much, we’ve just been making do. You’ll be helping me in the kitchen until we can find a cook that Isobel likes. Come down when you’re settled, and I’ll give you something to eat. Miss Isobel is very particular about how she wants things done. I’ve much to show you.’

Getting the job was one thing, but doing the daily work to Miss Carlisle’s satisfaction was another thing entirely. Annie discovered that Miss Marie’s real job was to serve as Miss Isobel’s secretary. Annie wasn’t really sure what that meant, except that Miss Isobel bossed Miss Marie around and Miss Marie said, ‘Yes, Isobel,’ and did as she was told. Sometimes Miss Marie called Miss Isobel ‘Izzy’ when no one else was around, which surprised Annie.

Miss Isobel had high expectations indeed. Miss Marie explained the best way to use the lemon oil to polish the furniture, and how to use the soft cloth to wipe the oil off and buff the wood to a high gloss. She explained how to wind the clocks every three days, and which vases Miss Carlisle liked to use for which flowers. Marie taught Annie the proper way to set out the towels in the bathroom, how to make a bed, and how to tidy the bedrooms and close the curtains at night. Mr Carlisle liked a carafe of cold water in the morning, while Miss Isobel liked hers at night. The house ran like a well-tuned engine, and it was Annie’s job to see that things went as smoothly as possible, especially on the rare occasions when Mr Carlisle was home.

Mrs Carlisle was a mystery to Annie. She smiled at Annie and spoke to her as though she were a friend rather than a servant. Only yesterday she offered to get Annie a cup of tea. Miss Marie was kind and gentle-natured, but Annie liked Mrs Carlisle the best. Mr Blackwell, a distant cousin with a tragic past, also lived in the house. Blackie was a sad old soul who had seen better days. He drank too much and often snuck Mr Carlisle’s good brandy of a morning, pouring it right into his tea when no one was looking. Annie had the impression he was scared to death of something or someone, but she was too busy to wonder what or who frightened him so. Annie didn’t see much of Mrs Carlisle or Mr Blackwell. The bulk of her work catered to the cares and demands of Miss Isobel Carlisle.

Annie had been nervous at first, afraid that some strange set of circumstances would allow her mother to find her. She scrubbed the front steps and polished the brass kick plate on the front door of the Carlisle home with one eye trained towards the square and the pavement, half expecting her mother and stepfather to come stomping up, demanding that she return home at once.

She didn’t want to think of the scene that would follow. Harold Green would act righteous and assert his influence as Annie’s stepfather, while her mother would nod in the background, afraid to disagree with the new husband who offered her financial security. They would insist Annie return home. A well-bred lady such as Miss Isobel Carlisle would have no choice but to give way to Annie’s parents. The thought of it brought Annie to her knees with fear.

But the days went by and Annie’s mother never appeared. As Annie settled in, her worries started to slip away. She took to her new job. She liked being busy. She polished and scrubbed and scoured and served until she fell into her tiny bed at night, exhausted from her efforts. She slaved her days away to forget the life she left behind, a happy life with her mum and dad and their lovely house.

After the first week, Miss Marie was so pleased with her work that she wrote up a list for Annie in the morning and left her to work on her own. Annie liked the idea that Miss Marie trusted her enough to let her work unsupervised. She did the tasks that she was assigned, and did other chores without being told to do so. Annie carried out her tasks while remaining appropriately in the background, unseen and unheard. None of this effort was lost on Miss Isobel or Miss Marie, who gave Annie a rise in salary after her third day.

By the end of her first week, the worry that her mother and Harold Green would find her started to fade. Annie’s mind was now free to notice things. And notice she did. With the artistic talent that had shown itself when Annie was a young child, she noticed the sunlight coming through the window in the entry hall, and the way the beams lit up the cut crystal vase that held the elaborate spray of roses. She noticed the long, dark shadows in Mr Carlisle’s office as she dusted, and the way the darkening shadows brought out the jewel tones in the thick rug that covered the floor.

She noticed the relationships between the members of the household. Miss Isobel bossed everyone around. She was especially bossy to Mrs Carlisle, who seemed to ignore Miss Isobel as though she weren’t there. Annie learned quickly to run the other way when it looked like the two women would meet.

On this particular day, Annie finished washing and putting up the breakfast dishes by eight a.m. She packed the wooden box that was kept in the cellar with a fresh bottle of lemon oil and a bundle of clean rags. She intended on polishing the wooden surfaces in Mr Carlisle’s office while he was at work. Annie opened the door and stepped into the room, surprised to find a camera in pieces along with a glass of brandy on Mr Carlisle’s desk.

‘Hello?’

‘Oh, Annie,’ Mr Blackwell – who was down on his hands and knees, out of sight, behind Mr Carlisle’s desk – struggled to his feet. ‘I’ve dropped a tiny screw to my camera.’ He nodded to the camera that lay on the table with the back removed. Three tiny screws rested on Mr Carlisle’s desk.

‘Do you want me to help you look?’ Annie wondered if she should come back later.

‘No, no,’ Blackie said. ‘It’ll turn up. I can get a replacement at the shop. Carry on.’ He downed the last of the brandy, packed up his camera, and let himself out of the office.

Once Blackie left, Annie got busy. She worked for a good thirty minutes, dusting the wooden surfaces before she added a bit of lemon oil and polished until they gleamed. She was down on her knees, dusting the base of a side table when she found the tiny screw. She tucked it in her pocket, and moved on with her work. It wasn’t until she got to the sideboard behind Mr Carlisle’s desk that she noticed one of the drawers was left open. She pushed it shut and didn’t think any more about it.

Pleased with a job well done, Annie returned the box of cleaning supplies to the cellar and removed the apron that now smelled of lemon oil. She made her way upstairs, moving through the house with a deliberate soft-footed silence. She met Marie on the upstairs landing.

‘I’ve put a treat on your bed, Annie. You’ve been working so hard,’ Marie said. ‘You can take a few hours for yourself. I’ll call when we need to get started in the kitchen.’

‘Thank you, ma’am.’

Annie hurried to her room. On her bed lay a sketchpad and a box of pencils. She delighted in it, and spent the afternoon curled up on her tiny bed, sketching the trees outside, secure in the knowledge that things would be okay.

Chapter Three (#ulink_573574dc-5e82-5662-b5b0-495afed9de58)

Cat wandered aimlessly after her attack. Her eye throbbed. Her ego was bruised. She wanted to be angry – her usual response to life’s injustices – but the only emotion she experienced was a burning fear that took away her ability to think in a rational manner. She thought about going to the police, but soon realised that reporting the assault would be a mistake. Reginald hadn’t explained why he needed Catherine to do the jobs he gave her, but he had been very clear about the secrecy required. She wondered what he would have to say about Cat’s attacker. He would have to say something, for the woman hadn’t been after Cat’s wallet. She had reached for the envelope.

Cat thought of Thomas Charles. He had said, ‘She won’t be back.’ How had he known that the attacker was a woman? He hadn’t been close enough to see her features clearly. How had he known that she wouldn’t come back? The time had come for Reginald to be honest with her. If he wouldn’t trust her, she would have to make other arrangements. What other arrangements? Cat nearly laughed out loud at the absurdity of that statement. She had no power in her relationship with Reginald. Until today she assumed she was doing menial courier work, a job thrown to her out of pity. Working for Reginald gave her the promise of independence. She wanted to cry out with frustration.

Cat started walking with no particular destination in mind. She couldn’t bear the thought of explaining her swollen face to Isobel, who would be quick with questions and even hastier with judgement. Rather than head towards the Carlisle house, she turned the opposite direction, grabbed a taxi, and gave her aunt’s address in Bloomsbury.

Aunt Lydia’s flat – one of four in a neat row, all brick, with a black front door and a half-moon window above – was two streets away from Bedford Square, a wooded park with ample benches to while away a summer day.

This neighbourhood wasn’t as posh as Kensington, but Cat preferred its utter lack of pretence. The front stoops weren’t scrubbed every day, nor were the pedestrians dressed in finery and jewels, but Cat had been happy here. She considered Bloomsbury her home. She walked up the steps to the front and rang the bell. When no one answered, she went down the steps to what used to be the service entrance to the below-street-level kitchen. She lifted a loose piece of flagstone and took the key that lay hidden there. She let herself into the kitchen.

She stood for a moment, taking in the familiarity of the house, letting the comfortable surroundings soothe her. Oh, how she wished she could escape back to this house, with its happy memories of her young adult life, to the time before she so naively married Benton Carlisle. Aunt Lydia had taken Cat under her protective wing after the motor-vehicle crash that killed her parents. Cat’s father was on leave for a week from some secret location where he served as a cryptographer. Her mother had gone to meet his train, and they planned to spend the week at home, together. Cat stayed behind to finish her schoolwork, so she could spend as much time with her father as possible. Until the knock on the door, the policeman with the sad eyes, and the news that changed Cat for ever.

Aunt Lydia had swept in, like an angel, and took Cat under her strong and capable wing. She had stayed with Cat just long enough to arrange the funeral and to see to the handling of the house. There was a small allowance that Cat would receive each quarter, enough money to live on if she stayed in Rivenby, the small northern village where she had lived so happily with her parents. But Lydia had other plans for Cat.

‘You need to figure out what you want to do with your life, darling. There’s no future for you here. Come to London and get yourself sorted out. You need to be around young people, darling. Rivenby will always be here, but you need to see a bit of the world before you settle.’

Cat, too shocked to make any decision on her own, capitulated without question and moved to London with her aunt. Now she stood in the foyer of their home, letting the familiarity sink in. It had been twenty years since her parents died. Once again Cat marvelled at the passage of time. She placed her palm flat on the wall, as if touching it like this would allow her to commit the comfort of the place to memory, as if the memory in turn would become a tangible thing she could keep with her.

She put the key back in its hiding place and went upstairs to the living room that overlooked the street. Now an old sofa covered with a sheet rested against the far wall. The big window flooded the room with light so vivid that its brightness jumped out from both of Aunt Lydia’s works in progress. One of the canvases portrayed Hector the Horse, the beloved character of the children’s books Aunt Lydia illustrated. The other was a still life depicting a large bouquet of flowers arranged haphazardly in an old milk jug that had at one time belonged to Cat’s mother.

The bunch of foxgloves, sunflowers, a stray imperfect rose, along with a handful of desiccated stems and twigs, didn’t appeal in their natural state. The flowers were on their last legs and the design of the arrangement was flawed. But Aunt Lydia used these flaws as the theme of her painting. Cat saw it right away. It gave the work an emotional pull that had successfully marvelled critics and enticed collectors for decades.

A large piece of wood positioned across two sawhorses served as her aunt’s work table. A cup of unfinished tea sat near a jar full of brushes and a box of paints. An open sketchpad lay on the table, revealing a pencil rendering of Hector the Horse arguing with a milkman. Next to it, a mock-up of the book was covered with Lydia’s unique angular scrawl.

An unbidden tear, hot and wet, spilled onto Cat’s cheek. Surprised, she wiped it away. She moved to the window and looked up and down the street before she went to the upstairs bathroom for a cool cloth.