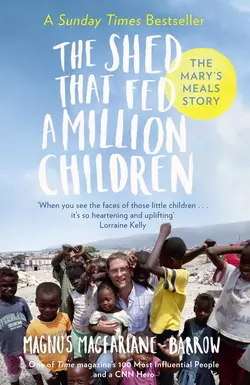

The Shed That Fed a Million Children: The Mary’s Meals Story

Magnus MacFarlane-Barrow

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Зарубежная религиозная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1011.29 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Speaking Volumes Christian Book of the Year 2016In 1992, Magnus MacFarlane-Barrow was enjoying a pint with his brother when he got an idea that would change his life – and radically change the lives of others.After watching a news bulletin about war-torn Bosnia, the two brothers agreed to take a week’s hiatus from work to help.What neither of them expected is that what began as a one-time road trip in a beaten-up Landrover rapidly grew to become Magnus’s life’s work – leading him to leave his job, sell his house and direct all his efforts to feeding thousands of the world’s poorest children.Magnus retells how a series of miraculous circumstances and an overwhelming display of love from those around him led to the creation of Mary’s Meals; an organisation that could hold the key to eradicating child hunger altogether. This humble, heart-warming yet powerful story has never been more relevant in our society of plenty and privilege. It will open your eyes to the extraordinary impact that one person can make.