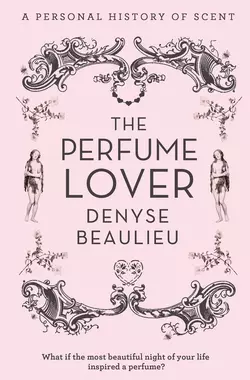

The Perfume Lover: A Personal Story of Scent

Denyse Beaulieu

‘Why couldn’t I be a perfumer’s muse? I’ve come such a long way in the realm of scent. In fact, I was never really meant to poke my nose into it …’The Perfume Lover by Denyse Beaulieu is an intimate journey into the mystery of scent.What if the most beautiful night in your life inspired a fragrance?Denyse Beaulieu is a respected fragrance writer; it is her world, her love, her life. When she was growing up, perfume was forbidden in her house, spurring a childhood curiosity that went on to become an intellectual and sensual passion.It is this passion she pursued all the way to Paris, where she now lives, and entered the secretive world of the perfume industry. But little did she know that it would lead her to achieve a fragrance lover’s wildest dream …When Denyse tells a famous perfumer of a sensual night spent in Seville under an orange tree in full blossom, wrapped in the arms of a beautiful young man, the story stirs his imagination and together they create a scent that captures the essence of that night. This is the story of that perfume.As the unique creative collaboration unfolds, the perfume-in-progress conjures intimate memories, leading Beaulieu to make sense of her life through scents. Throughout, she weaves the evocative history of perfumery into her personal journey, in an intensely passionate voice: the masters and the masterpieces; the myths and the myth-busting, down to the molecular mysteries that weld our flesh to flowers…The Perfume Lover is an unprecedented account of the creative process that goes into composing a fragrance, and a uniquely candid insider’s view into the world and history of fragrance.Your world will never smell the same.

Prologue

I am sitting in the perfumer’s lab, taking delicate cat-like sniffs of a slender blotting-paper strip dipped in orange blossom absolute. Though the flower has long been worn by brides as a symbol of purity, what I smell on this strip drops more than a hint of the earthier proceedings of the wedding night. In fact, the candid orange blossom, just like her sisters jasmine, gardenia and tuberose, hides quite a whiff of sex under her tiny skirts. No wonder the aphrodisiac essences of white flowers have always held pride of place in the arsenal of French perfumers. They are subtle reminders of the beast lurking within the beauty. Perfume is meant to go on a body; animal notes are what weld the suave scent of floral flesh to ours. Isn’t it a little hot in here?

While the sweet, narcotic orange blossom absolute unfolds its facets, the perfumer talks me through its more unexpected aspects. His words are like conjuring tricks: as he speaks, a snapped peapod, a whiff of hot tar just before a storm, a fatty smear of wax, a dusting of honeyed pollen spring from the strip. Orange blossom absolute is animal, vegetable and mineral all at once; it doesn’t quite smell like the flower it is extracted from. Still, there is enough of its ghost hovering over the blotter to tug at a distant memory. I close my eyes and let the fragrance seep into my mind, until it overwhelms all the other smells in the lab, bringing me back to the first time I ever breathed it in …

It had another, more poetic name for me then, bequeathed by the Moors to the Spanish language: azahar.

I am in Seville, standing under a bitter orange tree in full bloom in the arms of Román, the black-clad Spanish boy who is not yet my lover. Since sundown, we’ve been watching the religious brotherhoods in their pointed caps and habits thread their way across the old Moorish town in the wake of gilded wood floats bearing statues of Christ and the Virgin Mary. This is the Madrugada, the longest night of Holy Week, and the whole city has poured into the streets: the processions will go on until the dawn sky is streaked with hunting swallows. In the tiny whitewashed plaza in front of the church, wafts of lavender cologne rise from the tightly pressed bodies. As altar boys swing their censers, throat-stinging clouds of sizzling resins – humanity’s millennia-old message to the gods – cut through the fatty honeyed smell of the penitents’ beeswax candles.

Under the silver-embroidered velvet of her dais, the Madonna, crystal tears on her cheek, tilts her head towards the spicy white lilies and carnations tumbling from her float. She is being carried into the golden whorls of a baroque chapel, smoothly manoeuvred in and out, in and out, in and out – they say the bearers get erections as they do this – while Román’s hand runs down my black lace shift and up my thigh to tangle with my garter-belt straps. His breath on my neck smells of blond tobacco and the manzanilla wine we’ve been drinking all night – here in Seville, Holy Week is a pagan celebration: resurrection is a foregone conclusion and there is no need to mourn or repent. As the crowd shifts to catch a last sight of the float before the chapel doors shut behind it, the church exhales a cold old-stone gust. I am in the pulsing, molten-gold heart of Seville, thrust into her fragrant flesh, and there is no need for Román to take me to bed at dawn: he’s already given me the night.

Bertrand Duchaufour is leaning towards me with the rapt gaze of a child listening to a fairy tale. He removes his glasses and wipes them, nodding, before his lips curl into a boyish grin.

‘All those smells … it’s all there! Now that would make a very good perfume.’

I’ve just been leading one of the world’s best perfumers by the nose.

1

I’d have never imagined that some day I’d be telling Bertrand Duchaufour about my nights in Seville. When we first met in a radio studio in May 2008, I hadn’t even liked him much.

I’d only been writing about fragrance in earnest for a year at that point and I’d been very much looking forward to meeting Duchaufour. His off-beat, deeply personal compositions for edgy fashion labels like Comme des Garçons or the pioneer niche house L’Artisan Parfumeur had earned him star status among perfume aficionados as well as a reputation for artistic integrity. He was one of the people who’d eased fragrance out of its traditional set of references as projections of feminine or masculine personae: many of his compositions were olfactory sketches capturing the spirit of the places to which he’d travelled: Sienna in winter; a seduction ritual in Mali; a Buddhist temple in Bhutan; the Panamanian rainforest; a church in Avignon …

With his rectangular glasses, shaven pate and forthright demeanour, the forty-something perfumer certainly looked more like one of my artist friends than the sibylline master of a secret craft, and I was sure we’d get on fine. I was mistaken. Throughout the broadcast, Duchaufour was gruff and snappy. The host’s faux-naïve questions seemed to irk him; he let on that self-styled critics like myself or our fellow guest, the perfume historian Octavian Coifan, had better leave the thinking to the pros. It turned out he had good reason to be annoyed. He’d been led to believe he’d been invited to speak about his work. Minutes before going on the air, he was told that the topics of the day would be the high price of perfume and the absence of proper fragrance reviews. I understood why he was disgruntled and respected the fact that he didn’t try to ingratiate himself with us or the public, but I was disappointed just the same. Clearly, we weren’t going to be buddies. Still, the man made great perfumes and that was all that mattered. I didn’t have to like him personally to appreciate his work, and I certainly didn’t need him to like me.

So when I spotted him the following November at the raw materials exhibition organized by the Société Française des Parfumeurs where I had just been accepted as a member, I wondered whether I should even bother to say hello. But since we’d met, I’d managed to slip a foot in the door of a few labs: some of his colleagues seemed to think I was worth talking to. And more significantly, I’d fallen in love with his recent work. I felt he was shifting towards a more sensuous style I could actually connect with, and I’d just written a review of his latest fragrance, Al Oudh, an ode to Arabian perfumery pungent with sexy animal notes. ‘I love it when a man plays that kind of dirty trick on me,’ I’d concluded teasingly. It hadn’t occurred to me that he would ever read those words.

Duchaufour recognized me as I walked by: I was somewhat conspicuous with my apple-green coat and silver bob. Much to my surprise, he grinned and kissed me on both cheeks before congratulating me on the accuracy of my review. I hadn’t written it to please him, but I wasn’t about to let such an opportunity pass me by, so I instantly improvised a white lie. I was teaching a perfume appreciation course at the London College of Fashion in a month’s time, I told him (which was the truth), and I intended to discuss his work (also the truth, as of one second ago). It was the very first time I was to teach the course, which I’d been offered on the strength of my writing and talks I’d given to students in Paris. At first, I’d felt pretty confident I could swing it, but as the time to shut myself inside a classroom for three days with fifteen eager perfume lovers drew nearer, I was feeling a little jittery. I kept that to myself, but I did tell Duchaufour I’d appreciate his input (if anything, I’m a quick learner). Much to my relief, he nodded, still grinning:

‘You’re ready to learn more. Come over to the lab whenever you want!’

I wrote to him the very next day to take him up on his offer. After we’d exchanged a couple of emails, he suggested the use of the more familiar French form of address, tu, slyly adding, ‘It sounds more serious.’ So here I am, six months after our first, inauspicious encounter, perched on a chair in his tiny lab above L’Artisan Parfumeur’s flagship store and very ready indeed to learn more. The staid sandstone façade of the Louvre looms across the street; the searchlights of a bateau-mouche sweep from the Seine over the Pont des Arts. A three-tiered array of neatly labelled phials, each containing one of the hundreds of raw materials of the perfumer’s palette, throws amber, topaz and emerald glints under the desk lamp. A paper sheet lies next to a small electronic scale: the forty handwritten lines of the formula he is currently working on. At his feet, three shopping bags bulge with dozens of discarded phials – less than one per cent of his work, he says, ever makes it to the shop shelves. I’ve just tucked into my handbag a tiny atomizer of a scent of his due to be launched next spring, a tuberose perfume whose working title is ‘Belle de Nuit’. Though it was conceived long before we met, it feels like a sign: the tuberose resonates deeply with my life and loves, though he can’t possibly know it …

The churlish man who’d snubbed me has turned out to be warm, friendly and almost disconcertingly straight-talking; an intensely focused listener given to boyish bursts of enthusiasm. About the story of Seville I’ve just told him, for instance. He loves it, he says it would make a good perfume, but I don’t know him well enough to ascertain whether he’s the type to follow through or if this is just a perfumer’s version of a chat-up line. And certainly not well enough to ask him straight out if he’ll do it. Why would he bother with what must be, for him, just one of a hundred different ideas? On the other hand, why wouldn’t he? His ideas do have to come from somewhere. I didn’t tell him my story because I thought it would inspire him. It just came up as we were swapping tales of far-flung journeys. But now this idea is hovering between us and I realize I want this perfume to happen more than I’ve wanted anything in a very long time. Why couldn’t I be a perfumer’s muse? I’ve come such a long way in the realm of scent, Bertrand, you couldn’t ever know … In fact, I was never really meant to poke my nose into it.

2

My father couldn’t stand perfume. My mother only found out after they got married: she’d never been able to afford fragrance until then. Her first bottle of Chanel N°5 exited their flat soon after she’d brought it home. After that, she never wafted anything stronger than our doctor-recommended Ivory Soap.

As an added excuse for the ban, I was diagnosed with a slew of allergies: cat dander, dust mites, assorted pollens and … fragrance. But though I grew up on a continent where allergies are a way of life, my parents decided I would continue to be exposed to allergens until I built up a resistance to them. Our tabby still curled up wherever she pleased, tucking her squirming litters in my dad’s king-sized Kleenex boxes. Perfume was the only item on the doctor’s list to remain strictly verboten. I was six years old, and didn’t care. A childhood deprived of N°5 doesn’t quite register as abusive, and as long as we kept the cat, I was content.

So I don’t come equipped with the perfume lover’s standard-issue Proustian paraphernalia. No fond memories of dabbing myself with the crystal stopper of Mommy’s precious Miss Dior or kissing Daddy after he’d slapped his cheeks with Old Spice; no tales of lovingly collected perfume miniatures. Nothing but a trail of crumpled-up tissues strewn in an antihistamine-induced daze. I sometimes sneezed so hard I could’ve propelled myself downtown had I been on roller skates, and my allergies pretty much left me nose-blind. Anyway, in the Plastic Sixties, the suburbs of Montreal didn’t give off much more than the smell of burning leaves in fall and fresh-mown lawns in spring and summer – but at the first buzz of a lawnmower, I was sent indoors with my microscope, books and Barbie dolls, lest my bronchial tubes start shutting down. Scented memories of childhood? Access denied.

Bertrand Duchaufour frowns.

‘Really? Nothing?’

Could he help me kick-start my memory again? After all, it worked with the orange blossom last week … I’ve just dropped by to take my second informal lesson and we’ve been zipping through some of the raw materials he’s used in recent scents. I’m on familiar ground until he mentions something called yara-yara. Yara-yara? Sounds like I ought to start swaying my hips to it.

Out comes a blotter and into the phial it goes. He waves it under my nose. Diluted, yara-yara smells of orange blossom. At this concentration: penetrating, narcotic, with a side helping of mothballs. And somehow familiar.

‘This reminds me of the wintergreen top notes in tuberose.’

‘I wouldn’t say so … Here, I’ll show you the difference.’

He snatches another phial from the refrigerator and we repeat the blotter ceremony.

Ah … This I know. In fact, I feel like I’ve always known it …

As it turns out, I do have scented memories. But mine come courtesy of Big Pharma. Not only because antihistamines allowed me actually to breathe through the nose every once in a while, but because my father was a pharmacologist.

My visits to his lab as a little girl were thrilling and slightly scary events. The emergency chemical showers in the hallways hinted at the permanent risk of toxic splashes and horrible burns. My dad obviously did a dangerous, heroic job and his lab was one of the most glamorous places in the world to me. It was a smelly place too, permeated with the reek of disinfectants, the salty musky odour of guinea pigs and horsy effluvia – the lab manufactured an oestrogen extracted from the urine of pregnant mares, and we had to drive by the stables to park at the back of the building where my father worked.

Is that why I’m so happy to hang around perfume labs? And why I tend to be drawn to the weird notes that make people blurt out ‘Yuck, why would anybody want to smell of that?’ The animal and medicinal zones of the olfactory map attract me. For instance, the nostril-searing aroma of Antiphlogistine, an analgesic pomade found in every Canadian household since 1919, which was one of the few smells strong enough to burrow its way through my stuffy sinuses …

My growing pains may well have been one of the reasons why I fell in love with the fragrance aptly named Tubéreuse Criminelle for the way it assaults the nostrils when first applied. I am so addicted to it that, some days, I’ll spray myself time and again just to catch its venomous minty-camphoraceous blast before the scent subsides in creamy floral headiness. As it turns out, it’s also a blast from the past since tuberose and Antiphlogistine have one thing in common: the ice-green burn of a molecule called methyl salicylate.

I know. Those chemical names are a bitch. You don’t need to learn them to appreciate perfume, but it helps if you want to make sense of it. Odorant molecules are the building blocks of perfumery. A natural essence may contain hundreds of them. The ones that contribute the most to its smell can be isolated and synthesized. Each will yield a distinct facet of the original essence – of several, in fact, since the same odorants keep popping up all over nature. These molecules can then be assembled to conjure an olfactory illusion in a few broad strokes: when your fragrance has a jasmine note, there’s a good chance it comes from a combination of the chemicals naturally found in jasmine rather than its actual essence, of which there might only be a few drops just so the advertising copy doesn’t lie. Taken separately, those molecules won’t actually smell of jasmine. But if you blend benzyl acetate (floral, apple, banana, nail polish), hedione (green, citrusy, airy), jasmolactone (buttery, fruity, coconut, peach) and indole (mothballs, tooth decay), you’ll get a decent impression of the flower that’s a lot cheaper to produce than the real stuff. Aromatic materials, natural and synthetic, can also be combined to reproduce the scent of a flower whose essence can’t be extracted, such as gardenia, lily-of-the-valley or lilac. And that’s not even mentioning the synthetics that smell entirely man-made … You didn’t think the musk in your Narciso Rodriguez for Her grew on bushes, did you?

Despite the breathless sales pitches, if fifteen per cent of what’s in your bottle comes from a thing that was alive at some point, you’re doing well. Any more would cut into profit margins. Natural materials are not always more expensive than synthetics, but they’re harder to source. A drought, a flood, a war will make prices shoot up. Crops don’t smell exactly the same from one year to another, so that you may have to mix essences from different sources to achieve the same effect in every batch of perfume, a practice called the communelle. With synthetics, on the other hand, you can produce batch after batch without worrying about Nature’s tantrums or geopolitical flare-ups.

It’s not just a matter of price or convenience. Glamorous, exotic and irreplaceable as natural essences may be, it is to synthetics that we owe modern perfumery, and many of the greatest breakthroughs came about as perfumers learned to use them. Synthetics allowed perfumers to structure their compositions by strengthening the relevant facets of natural materials; to conjure the desired effect with a few notes rather than having to draft the entire orchestra of the natural essence; to produce entirely new perfumes. In fact, without synthetics, perfumery would exist neither as an industry, nor as an art.

When Gabrielle Chanel asked Ernest Beaux to come up with a fragrance for her couture house, she told him two things, or so the legend goes (Chanel was not above retro-engineering her life story when it suited her purposes). First: ‘A woman must smell like a woman, not like a rose,’ a dig at her arch-rival of the time, the couturier Paul Poiret, whose logo was a rose and whose perfume line, the first ever to be launched by a couturier, was named Les Parfums de Rosine after one of his daughters. Chanel, a keen follower of the avant-garde, thought the figurative school of perfumery – ‘a rose is a rose is a rose’ – was as hopelessly outdated as the plumed and flowered hats she’d replaced with straw boaters. She didn’t care much either for the vampy scents her contemporaries doused themselves in. Her perfume, she decreed, should smell as clean as the soap-scrubbed skin of her friend, the famous courtesan Émilienne d’Alençon. But on the eve of the 20s, luxury perfumes still relied extensively on natural essences, many of which ended up leaving a rather rancid odour on the skin because flower extracts were often obtained by spreading the blossoms on mesh frames smeared with fat, a method called enfleurage. Fortunately, Ernest Beaux had a trick up his sleeve, a synthetic material he’d already been playing around with …

Since the late 19th century, organic chemistry had made giant steps, providing perfumers with synthetic materials that were stronger, cheaper, more stable and more readily available than natural materials (availability would particularly become an issue during World War I and its aftermath). These new synthetics allowed perfumers to forego references to nature. Just as the invention of the paint tube had allowed the Impressionists to set up their easels wherever they pleased to catch variations in light, or as the advent of photography had freed painters from naturalistic representation, technical progress fuelled new paradigms in perfumery. But synthetics were often harsh-smelling and only the best perfumers had the skill, the inspiration or the audacity to blend them into a high-quality product. Ernest Beaux was such a man.

On their own, aliphatic aldehydes give off a not particularly pleasant smell of citrus oil mixed with snuffed candles and hot iron on clean linen. They were mainly used in the synthetic versions of natural essences like rose because they had the property of boosting smells, which meant they were mostly found in cheaper products, or in small amounts in finer fragrances to produce fresh, clean, soapy notes – for instance, in Floramye by L.T. Piver, which happened to be a favourite of Mademoiselle Chanel’s … Beaux’s genius was to use aldehydes both for their booster effect and for their specific smell; to blend them with the noblest, most expensive raw materials; to figure out that they could produce just the required freshness by lifting the heavy scent of the oils and counteracting their rancidness. In the formula of what was to become N°5, he injected an unprecedented one per cent. Later on, he would write that he had been inspired by the icy smell of lakes and rivers above the Arctic Circle.

Did he produce the formula to Gabrielle Chanel’s specifications? Or had he already composed it for the company he was working for when Chanel sought him out? Beaux worked for Rallet, a supplier to the Tsar’s court, which had been forced by the Bolshevik revolution to move its operations to the South of France. Some industry old-timers claim that as Rallet didn’t have the means to exploit its products on a large enough scale (most of its assets had been abandoned in Russia), it decided to offer the formula of its Rallet N°1 to Chanel …

Whatever the truth of the story, the official legend is as much a part of the perfume as its actual substance: a masterpiece in its own right. But it was that very legend that clouded my perception of N°5 until I stumbled on a pristine, sealed 30s bottle that ripped the veil. Then, at last, I understood its radiant, abstract beauty because the raw materials in it were much closer to the ones Ernest Beaux had used to compose it; their subtle differences were sufficient to jar me out of the cliché that N°5 had become. If I love N°5 now, it is because of the sheer artistry of it, and I discovered that artistry not because it awoke fond memories, since I had none, but for the opposite reason: because of its strangeness. That strangeness is the very reason that led me to the once-forbidden realm of perfumery.

Some people have a signature fragrance that expresses their identity and signals their presence; its wake is an invisible country of which their body is the capital. I’m not one of those people.

I am a scent slut.

‘To seduce’ means ‘to lead astray’, off familiar paths and into thrillingly uncharted lands. To me, perfume is not a weapon of seduction but rather a shape-shifting seducer. I have been exploring the world of fragrance in the same way, and for the same reasons, that I’ve travelled erotic territories, spurred on by intellectual curiosity, sensuous appetites and the need to experiment with the full range of identities I could take on. And just as my experimental bent has driven me to different men, situations and scenarios to find out what I would learn through them, it has led me to different scents.

Perfume is to smells what eroticism is to sex: an aesthetic, cultural, emotional elaboration of the raw materials provided by nature. And thus perfumery, like love, requires technical skills and some knowledge of black magic. Both can be arts, though neither is recognized as such. And I’ve been studying both in the capital of love and luxury, Paris, where I settled half a lifetime ago. It is in Paris that I learned about l’amour; in Paris that I stepped through the looking glass into the realm of scent. I’ve had good teachers: discussing the delights of the flesh as passionately and learnedly as you would speak about art or literature is one of the favourite pastimes in my adopted country. Here, pleasure is intensified by delving into its nuances. By putting words to it. La volupté is taken very seriously indeed, a worthy subject for philosophizing in the boudoir. And so I’ve come to think of perfumes as my French lovers – a way for gifted artists to seduce me, parlez-moi-d’amour-me and reflect the many facets of my soul in eerily perceptive ways …

Blame Yves Saint Laurent and the Frenchwoman who revealed his existence to me via the first drop of perfume ever to touch my skin.

3

I was eleven when I decided I’d be French one day. Not only French, but Parisian. And not only Parisian, but Left Bank Parisian: glamorous, intellectual and bohemian.

When she moved into the house next door with a German engineer husband, Geneviève didn’t quite replace The Avengers’ Mrs Emma Peel as my feminine ideal. Despite her closetful of clothes with Paris labels and her collection of French glossy magazines, Geneviève was still a housewife stuck in the suburbs of Montreal and even at eleven I knew I’d never be that. But when she opened that closet and those magazines, she drew me into a world where she herself had probably never lived. The world I live in now.

The scientific community is nothing if not international, but though my parents’ cocktail parties could have been local branch meetings of UNESCO, I’d never met a French person before. Next to Geneviève’s, my Quebec accent sounded distressingly rustic and I soon applied myself to mimicking her patterns of speech, which got me nicknamed ‘La française’ in the schoolyard. As soon as my homework was done I’d wiggle through a hole in the honeysuckle hedge and scratch at her back door.

Geneviève was in her late twenties, childless and homesick; she’d followed her husband as he was transferred from country to country, lugging a battery of Le Creuset pots and pans and a closetful of pastel dresses in swirly psychedelic or whimsical floral patterns which she’d happily model for me, and sometimes let me try on. I’d clack around in her pumps and twirl in front of the mirror. Sometimes we’d both dress up and stage make-believe photo shoots inspired by Vogue. Those were grand occasions since Geneviève would also let me pick from the array of cosmetics on her dressing table and carefully do my face. We’d model the looks in our very favourite makeup ads, the ones for Dior: pale, moody, smoky-eyed beauties with thin scarlet lips.

But there was one particular item on the dressing table I steered well clear of: a blue, black and silver-striped canister that said ‘Yves Saint Laurent Rive Gauche’. What if my lungs seized up? I hadn’t suffered an asthma attack since the age of six, but I’d witnessed my dad’s discomfort if we walked within ten feet of the perfume counters in the local shopping mall, so I wasn’t taking any chances. Geneviève gave a Gallic shrug when I finally, cringingly, explained about the allergies.

‘You North Americans really indulge your little bobos, don’t you? Here, look at this …’

She set her smouldering Camel in an ashtray, pulled out the scrapbook where she kept magazine cuttings and pointed to the picture of a slender young man with huge square glasses flanked by a lanky blonde in a safari jacket and a cat-eyed waif with a gypsy scarf on her head. The trio exuded a loose-limbed pop-star glamour. This was, Geneviève explained, Yves Saint Laurent, the greatest couturier in France, with his muses Betty Catroux and Loulou de la Falaise. And Rive Gauche was the perfume he’d named after his new boutique in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, the first place she’d head for when she went back to Paris.

From the ads I’d spotted in my mother’s Good Homemaker magazine, I knew perfumes ought to have fancy glass bottles and evocative names like Je Reviens or Chantilly. There was nothing poetic about that metal canister. And Rive Gauche, what kind of a name was that? So Geneviève showed me the ad for Rive Gauche: a redhead in a black vinyl trench coat strolling by a café terrace with a knowing smile. Rive Gauche, plus qu’un comportement, it said; Rive Gauche, un parfum insolite, insolent. ‘More than an attitude. An unusual, insolent perfume.’

My friend explained about the Paris Left Bank, the jazz clubs and bohemian cafés on the boulevard Saint-Germain she used to walk by as a teenager to catch a glimpse of les philosophes, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. I’d read about Socrates in my children’s encyclopaedia but hadn’t fathomed that there were living philosophers or that they could even remotely be thought of as cool. At my age, cool was still a difficult concept to grasp.

‘Like pop stars, you mean?’

Geneviève nodded. Yves Saint Laurent, she went on, expressed the spirit of the Left Bank: youthful, rebellious and free. I couldn’t quite figure out how the soapy, rosy-green scent that clung to Geneviève’s clothes could reflect notions like youth, rebellion, freedom or insolence, and I had no idea of what constituted an ‘unusual’ fragrance. But I did half-guess from her wistful gaze that Geneviève, trapped in a Montreal suburb where there were no cafés haunted by chic bohemian philosophers or couturiers – there weren’t even any sidewalks! – longed for that lost world. A world captured in that blue, black and silver canister …

One afternoon, our orange school bus dropped us off early so that we could prepare for the year-end recital: I sang in the choir, humiliatingly tucked away in the last row with the boys because I’d suddenly grown taller than all the girls. Geneviève had promised that, for the occasion, she would do my hair up in her own signature style, a complex hive of curls fastened with bobby pins. I scrunched my eyes and held my breath as Geneviève stiffened her capillary edifice with spurts of Elnett hairspray.

‘There you go … Have a look!’ she said, waving a Vogue around to clear the fumes.

I opened my eyes to a chubby-cheeked version of Geneviève. The chignon was practically as high as my head: I’d tower over the boys too.

‘And now …’ Geneviève reached for her Rive Gauche. ‘As a special treat, I’ll let you wear my perfume … In France, an elegant young lady never goes out without fragrance.’

That spritz of Rive Gauche didn’t kill me; in fact, it made me feel better than I’d ever felt, so grown-up, so important – an eleven-year-old girl with the newest perfume from Paris! That’s when I resolved that when I grew up, I’d be like Geneviève, and never leave the house without a drop of perfume. And it would be French perfume, even if I had to swim across the Atlantic to get it.

4

What is it about the French and perfume? Draw up a list of the greatest perfumes in history. Shalimar, Mitsouko, N°5, Arpège, Femme, L’Air du Temps, Diorissimo? French. Study the top ten sellers in any given country. The labels may be American, Italian or Japanese, but the perfumers who composed them? At least half are French and most of the others are French-trained.

When Bourjois, the cosmetics company that owned Chanel perfumes, decided to put out a fragrance called Evening in Paris in 1928, they knew full well that they were launching the ultimate aspirational product. For millions of women, that midnight-blue bottle would hold the prestige and romance of the French capital within its flanks – it was the closest most would ever come to the Eiffel Tower. Judging from the number of Evening in Paris bottles that keep popping up on auction websites, they were right. For generations, ‘French perfume’ was the most desirable gift, short of mink and diamonds, and a lot more affordable.

But why is it that those two words, ‘French’ and ‘perfume’, have been said in the same breath for centuries? In other words: why is perfume French? If you ask most people in the industry, they’ll answer, ‘Well, because of Grasse, I guess,’ Grasse being the town in the South of France where perfumery developed as an offshoot of the leather-tanning industry. Tanning products were rank, so fine leathers were steeped in aromatic essences to counteract the stench, and Grasse enjoyed a particularly favourable microclimate for growing them. Though most of the land has now been sold to real-estate developers, it is still very much a perfumery centre, with several labs and a few prominent perfumers based in the area. But ‘Grasse’ doesn’t answer the question. There were other places in the world, like Italy and Spain, where a cornucopia of aromatic plants could be grown; where botanists, alchemists and apothecaries studied them, refined extraction processes, experimented with blends. There must be another reason why it was in France that perfume went from a smell-good recipe to liquid poetry; why it was here and nowhere else that modern perfumery was born, thrived and gained international prestige.

So why indeed? If anyone can answer the question I’ve been asking myself since I was eleven, it is the historian Elisabeth de Feydeau. We’ve just been enjoying an al fresco lunch in a garden gone wild with roses, lush with vegetal smells rising in the afternoon heat. A tall, chic blonde with a sweet, sexy-raspy voice, Elisabeth was formerly the head of cultural affairs at Chanel; she teaches at ISIPCA, the French school of perfumery, as well as acting as a consultant for several major houses; she wrote a book about Marie-Antoinette’s perfumer and a history of fragrance. So as we nibble on petal-coloured cupcakes, Elisabeth graciously shifts into teaching gear. I have indeed come to the right place for an answer, she tells me; the sacred union between France and fragrance was sealed right here where we’re sitting, in Versailles.

If Catherine de’ Medici hadn’t come to France in 1553 to marry the future King Henri II, perfume might well have been Italian. Not only did Italy enjoy a climate allowing the cultivation of the plants used in perfumery, but with Venice lording it over the sea routes, all the precious aromatic materials of the Orient flowed into the peninsula. And in the dazzlingly refined Italian courts of the Renaissance where the young Duchess Catherine was raised, perfume-making, intimately linked to alchemy, was a princely pastime practised by the likes of Cosimo di Medici, Catarina Sforza and Gabriella d’Este. Italian alchemists had started to divulge their methods of distillation and many of their perfumery treatises had already been translated. When Catherine de’ Medici arrived with her perfumer Renato Bianco in tow, she brought along the Italian tradition in all its refinement.

The French perfume industry was centred in Montpellier, where research on aromatic substances and distillation was carried out at the faculty of medicine (one of the oldest in the world, founded in 1220), and in Grasse, where skins imported from Spain, Italy and the Levant were treated. Up to then, perfumery had remained a subsidiary activity for apothecaries and tanners. Spurred on by the Italian fashion for scented clothes, leather items, pomanders and sachets, it developed into a luxury trade.

But the true turning point came from the scent-crazed king who had determined to transform his court into the crucible of elegance: it was under the reign of Louis XIV (1638–1715) that the French luxury industries acquired the excellence and prestige they still boast today. And that spectacularly successful marketing operation was a very deliberate political endeavour … During his mother Anne of Austria’s regency the young king had lived through the War of the Fronde, an uprising of the nobility that had threatened the very existence of the monarchy. To keep his noblemen under control, Louis XIV decided to move his court away from Paris to the newly built Versailles. There, he transformed his most trivial activities – getting out of bed, being groomed and dressed and even using the ‘pierced chair’ (the 17th century version of the toilet, known in England as ‘The French Courtesy’) – into a series of ritual displays which courtiers had to attend to curry favour with the monarch. By compelling them to follow the fashions he launched and to participate in the court’s lavish spectacles, the Sun King made sure they had no time or money to plot against the Crown. To imitate him, courtiers turned their toilette (named after the toile, the piece of cloth onto which cosmetics were spread out) into a social occasion. Celebrity endorsement was invented in Versailles. If, say, the king’s current favourite used some new pomade or scented powder in front of her coterie, she might create a stampede for it. This bit of information would be carried by a brand-new medium, the fashion gazette.

This was the other reason behind Louis XIV’s marketing operation. Fashion would radiate from his royal person to his court, from the court to Paris, and from Paris to the entire world, which would draw much-needed currency into the kingdom. His minister of finance Jean-Baptiste Colbert therefore set out to build up the French luxury industry, sending spies abroad to steal trade secrets and poach skilled artisans, and finding out which professional corporations were likely to become economic forces for France. Colbert made a deal with the guilds: they would be granted privileges and exempted from certain taxes provided they came up with the best and the most beautiful products. ‘The château of Versailles became, quite literally, a showroom designed to display the know-how of French craftsmen to foreign monarchs and dignitaries. There was an order book when you came out!’ chuckles Elisabeth de Feydeau. Paris, with its fancy shops staffed by well-turned-out young women, glittering cafés and public gardens, became an extension of that Versailles showroom, spurring on further demand for made-in-France luxury items, which in turn spurred on creativity, as perfumers refined their art to meet the exacting tastes of their snobbish clientele.

The perfume and cosmetics industry was one of those encouraged by Colbert. He boosted its profitability by setting up the Company of the Eastern Indies to ensure the supply of exotic ingredients while plantations were developed in Grasse. Again, Louis XIV provided the best possible celebrity endorsement: his orange blossom water, which came from the trees in the Versailles orangery, was exported all over the world. It was the only perfume the Sun King tolerated in his later years: in the last decade of his reign, perfumes gave him migraines and fainting spells which may have been psychosomatic, or due to allergies. ‘No man ever loved scents as much, or feared them as much after having abused of them’, wrote the memoirist Saint-Simon.

In fact, the royal scent-phobia just about killed the industry. A Sicilian traveller noted that ‘foreigners enjoy in Paris all the pleasures which can flatter the senses, except smell. As the king does not like scents, everyone feels obliged to hate them; ladies affect to faint at the sight of a flower.’ And indeed, though Versailles and Paris reverted to their old fragrant ways under the gallant reign of Louis XV, one of the most groundbreaking products in the history of the industry came not from Grasse, Montpellier or Paris, but from Italy via Cologne, Germany, where Johann Maria Farina launched his Aqua Mirabilis. The ‘Miraculous Water’, a light, bracing blend of citrus, aromatic herbs and floral notes in an alcoholic solution, is known to this day as ‘eau de Cologne’. This new style of perfumery, a departure from the heavy, animal notes used by Louis XV’s libertine court, was well in tune with the tentative progress of personal hygiene practices and the tremendously fashionable back-to-nature philosophy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Noses and sentiments were becoming more delicate …

As Rousseauism swept through Europe, clothing, interiors, gardens and fragrances took on the tender floral tones that most flattered the fresh complexion of the kingdom’s premier fashionista, Queen Marie-Antoinette. It was under her reign that Paris consolidated its status as the trend-setting capital of the world. By the time her husband Louis XVI was crowned in 1774, the rigid etiquette of Versailles set up by the Sun King had lapsed and, as a consequence, the status of the aristocracy was rather less exalted than it had been. To stay ahead of the rising bourgeois class, the ladies of the court, led by Marie-Antoinette, resorted to the only thing that could keep them one step ahead of the commoners, however wealthy they were: fashion. In fact, this is how fashion as we know it – the latest trend adopted by a happy few for a season before trickling down to the middle classes – came into existence. Marie-Antoinette plotted the newest styles with her ‘Minister of Fashion’, Rose Bertin. She and her entourage would retain exclusivity for a set period, after which the item could be sold in Bertin’s Paris shop, Le Grand Mogol, and every woman who could afford it could dress herself ‘à la reine’. This, in itself, was a revolutionary move. As Elisabeth de Feydeau explains it, etiquette demanded that the Queen use Versailles suppliers. But Marie-Antoinette wanted her suppliers to go on living in Paris to sniff out the zeitgeist. Louis XIV had established the prestige of the French luxury trades, ‘but that little twist you can only find in Paris, that je ne sais quoi that makes Parisian women incomparable – and this comes out very clearly in the writings of foreign visitors of the period – emerges in the 18th century. There is a word that sums this up: elegance.’

With her gracious manners and lively laugh, Elisabeth herself is the very type of Parisienne foreign visitors have admired since Marie-Antoinette’s day. Even the dishevelled garden where we converse has just a touch of the négligence étudiée that distinguishes chic Parisian women from their fiercely put-together New Yorker or Milanese counterparts. I can easily envision Madame de Feydeau in one of the supple white muslin gowns the queen made fashionable in the 1770s, presiding over an assembly of philosophers and artists with whom she could match wits. Because this is what Paris gave to the world, through the learned, elegant women who led its social life and were deemed worthy intellectual sparring partners by the brightest men of the age: wit rather than pedantry; a way of thinking of life’s pleasures with the finely honed weapons of philosophy. You’ve always wondered why the French appreciate smart women? Why women don’t drop off the radar after the age of forty? There you have it. Where the art de vivre is a serious pursuit, the women who have turned it into an art form are valued indeed. And this, we owe to the 18th century.

Thus, it isn’t surprising that Elisabeth turned her attention to that very period with A Scented Palace: The Secret History of Marie-Antoinette’s Perfumer. Jean-Louis Fargeon rose to the top of his profession just as perfumery was severing its ties with tannery and glove-making to become a fully fledged trade – another turning point in the history of the industry. If he left his native Montpellier, it was because he knew that he could only succeed if he breathed in the incomparable esprit de Paris. And if he nabbed the world’s most prestigious customer, it was because he was incomparably skilled at composing the delicate floral blends that reflected the era’s craving for a simpler, more natural life … Fargeon’s status as the queen’s perfumer almost cost him his head during the French Revolution: he escaped the guillotine by a hair’s breadth simply because, as he was rotting in jail, Robespierre was executed, thus ending the Terror that cost the lives of over forty thousand people, a full third of whom were craftsmen. And the Revolution did, in fact, almost kill off the French perfume industry, not only because it dissolved the guild of perfumers, which reeked of aristocratic privilege, but because most of its clients were either beheaded or exiled. By the time a new court was formed around the Emperor Napoleon, tastes had changed. Though the Empress Josephine was inordinately fond of musk, he preferred her natural aroma, famously asking her not to wash for several days because he was returning from a military campaign. And he loathed perfume apart from eau de Cologne, which he carried everywhere with him, literally showered with and even consumed by dunking lumps of sugar in it. After his fall, the French luxury trades declined while the English industry gained ascendancy.

‘Then, in 1830, French perfumers came up with the phrase “Invent or perish”,’ reveals Elisabeth. ‘They realized that the world had changed, that the perfumery of the old regime was no longer possible, and from 1840 onwards, French perfumery started rebuilding itself.’

But the period was dominated by bourgeois, puritanical values, and vehemently rejected the wastefulness and deceit of cosmetics and fragrances. ‘Perfumes are no longer fashionable,’ sniffed a French Emily Post in 1838. ‘They were unhealthy and unsuitable for women for they attracted attention.’ At most, a virtuous woman could smell of flowers, and not just any flowers: heliotrope, lilac, carnations or the whitest possible roses. Master perfumers like the Guerlains – the house was founded in 1828 – undoubtedly made lovely blends for their wealthy customers, but the bulk of scents were mainly used as personal hygiene products in an era when most homes didn’t have running water. Fragrance was no longer a luxury: it was just a way of smelling nice, of removing bad smells.

Paris, however, remained the capital of fashion: it was here that the Englishman Charles Frederick Worth established himself as the world’s first star couturier, under the reign of Napoleon III. But French perfumery would have lagged behind without the handful of visionaries who propelled it into the 20th century.

One of these men was Jacques Guerlain, who authored a series of shimmering, impressionistic masterpieces still produced and adored to this day: Après l’Ondée, L’Heure Bleue, Mitsouko and Shalimar. But an upstart was hot on his heels, a self-taught perfumer untrammelled by tradition and therefore willing to use the new, more brutal synthetic materials to conjure vibrant Fauvist compositions in tune with the scandalous Ballets Russes. It was the Corsican François Coty, known as the Napoleon of perfumery, who democratized fine fragrances by launching cheaper ancillary lines, whereas Guerlain perfumes were still sold to a very select clientele. Soon, he was selling 16 million boxes of talcum scented with L’Origan in France alone. Guerlain had reinvented the heritage of traditional perfumery: Coty turned it into a worldwide industry and took it into the 20th century.

But it was haute couture that truly transmogrified Paris perfumes into the stuff dreams were made of for millions of women around the planet – the stuff that would make a young girl in the suburbs of Montreal decide she would be Parisian one day because of a spritz of Rive Gauche. ‘As long as you’re in a one-to-one relationship with your customer, like Jean-Louis Fargeon was with Marie-Antoinette, or Jacques Guerlain with the clients who came to his salon, you can explain your perfume, make it loved,’ Elisabeth tells me. ‘But when fragrance becomes an industry, how do you sell it as a luxury item? Perfume needs to be supported by image. And who but world-famous Paris couturiers could provide a better one?’

The first couturier to launch a perfume house was Paul Poiret, in 1911. The Pasha of Paris, as he was dubbed, was practically the first to turn fragrance into a concept, with a dedicated bottle and box for each product. But he made the marketing mistake of not giving it his own name. The first to do that, in 1919, was Maurice Babani, who specialized in Oriental-style fashions and whose perfumes bore such exotic names as Ambre de Delhi, Afghani or Saigon. Gabrielle Chanel followed suit in 1921, but her N°5 only went into wider production in 1925, when she partnered up with the Wertheimers who owned Bourjois cosmetics. By that time, other couturiers like Jeanne Lanvin and Jean Patou had realized perfume was a juicy source of profit and got in on the game. Thus it was that in the first decades of the 20th century, French couture and perfumery began an association from which the prestige of the most portable of luxury goods – a few drops on a wrist or behind the ear – would durably benefit.

But it wasn’t all a canny exploitation of the Parisian myth. French perfumery truly was the best and the most innovative; French perfumers did create most of the templates from which modern perfumery arose. Why? Perhaps because, ever since Colbert’s day, Paris had been a laboratory of taste, not only in fashion or perfume, but also in cuisine and decoration. A discerning clientele of early adopters, eager to discover new styles and new fashions, spurred the purveyors of luxury goods into devising ever more refined, more surprising, more delightful products, thus bringing their craft to an incomparable degree of perfection. Function, as it were, created the organ. In this case: the best noses in the world.

5

However, my very first perfume was not French, but American. Its frosted apple-shaped bottle has managed to survive the decades without getting carried off in my mother’s garage sales. It followed my parents when they sold the house where I grew up. It still taunts me whenever I go home to visit …

Geneviève certainly meant well when she picked Max Factor’s Green Apple for me as a parting gift before she followed her husband to Saskatchewan. She must have been told it was suitable for young girls. I hated it. Unlike Rive Gauche, which had given me a glimpse of the woman I aspired to become, Green Apple didn’t tell a story. Or if it did, it was a story I didn’t want to hear in my first year in high school; a story that contradicted my training bra and the white elastic band that had already cut twice into my budding hips, holding up Kotex Soft Impression (‘Be a question. Be an answer. Be a beautiful story. But be sure.’) What it said was: ‘Don’t grow up.’

Wear Green Apple: He’ll bite, insinuated the Max Factor ad. Never mind that apple candy has never registered as a powerful male attractant and that I’d never been kissed by a ‘he’, much less bitten. I’d attended Sister Aline’s catechism class and I got the Garden of Eden reference behind that slogan, thank you. But to me, that bottle wasn’t the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. It was Snow White’s poison apple. And an unripe one at that, just like me. The only apple-shaped things I wanted to own were starting to fill my A-cups.

When the good people at Max Factor put out their apple-shaped bottle, conjuring memories of Original Sin and of the Brother Grimms’ oedipal coming-of-age tale, they tapped into a symbolic association which Dior would later fully exploit with another potion in an apple. But that one would be called Poison: the myth of the femme fatale poured into amethyst glass and wrapped in a moiré emerald box – purple and green themselves hinting at venom and witchcraft …

When it was launched in 1985, I’d long grown out of my Green Apple trauma and into the twin addictions of ink (usually purple) and perfume. I hoped to become a writer, and a fragrant one at that. I’d just finished writing my Masters dissertation on 18th century literature and I was struggling through my first academic publication in France, an essay on Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, when I stumbled on an article about Poison, ‘a spicy perfume blending Malaysian pepper, ambergris, orange blossom honey and wild berries’. This was particularly serendipitous: the whole point of my essay was that the adulterous Emma Bovary’s aspiration to become a romantic heroine despite the mediocrity of her provincial surroundings was the result of her mind being poisoned by cheap romantic novels. A farmer’s daughter married off to a small-town doctor, she grew so frustrated at not being able to live out her girlhood fantasies that ‘she wanted to die. And she wanted to live in Paris.’ Emma never got closer to Paris than Rouen but she managed to run up such a debt with the local frippery pedlar that her house and belongings had to be auctioned off, whereupon she poisoned herself with arsenic. In my essay, I contended that the ink she had absorbed when reading romances had poisoned her every bit as much as the rat-killer.

‘What I blame [women] for especially is their need for poetization,’ Flaubert wrote in 1852 to his lover Louise Colet. ‘Their common disease is to ask oranges from apple trees … They mistake their ass for their heart and think the moon was made to light their boudoir.’ As neat a forecast as ever was of what would drive perfume advertising one century hence. Weren’t we all modern embodiments of Emma Bovary, I thought, seeking magic potions to transform our lives? To die or live in Paris … And now, a legendary couture house where a latter-day Bovary could well burn through her husband’s earnings was selling an intoxicating – and perhaps toxic – dream of romance and glamour under the slogan ‘Poison is my Potion.’

When the CEO of Christian Dior Parfums, Maurice Roger, first decided, in 1982, to launch Poison, the industry had been undergoing deep mutations. Perfume houses were being bought up by multinational companies, and their new products had to have global appeal. With the blockbusting, take-no-prisoners Giorgio Beverly Hills, America was starting to bite into a market that had hitherto been dominated by France. To make itself heard around the world in the brash, loud, money-driven 80s, the house of Dior had to create a shock. This, Maurice Roger knew, meant renouncing the variations on the name ‘Dior’ which had been used to christen all their feminine fragrances from the 1947 Miss Dior to the 1979 Dioressence; it meant foregoing Parisian ‘good taste’ and striking with an unprecedentedly powerful scent and concept. It meant re-injecting magic, mystery and a touch of evil into something that was no longer for ‘special moments’ (think of that fragrance your grandmother kept on her dressing table and only dabbed on when she pulled out the mink and pearls), no longer a scent to which women were wedded for life, but a consumer product. The magic, this time, would be entirely marketing-driven, though the fragrance itself, selected out of eight hundred initial proposals, required over seven hundred modifications before reaching its final form.

The promotional campaign kicked off with a ‘Poison Ball’ for 800 guests at the castle of Vaux-le-Vicomte hosted by the French film star Isabelle Adjani. And, if the bottle was reminiscent of the story of Snow White, the advertising film conjured another fairy tale, The Beauty and the Beast. Its director, Claude Chabrol, never hinted that the would-be femme fatale might be the one to succumb, Bovary-style, to the potion it touted. But I’m sure Chabrol, who would go on to direct an adaptation of Madame Bovary, had a thought for one of his film heroines, the eponymous and fragrantly named Violette Nozière, a young prostitute found guilty of poisoning her parents in 1934 (both characters played by the exquisitely venomous Isabelle Huppert).

‘Who would offer someone a gift of poison?’ the New York Times fashion editor wailed. And Dior’s blockbuster did, in fact, wreak havoc in its wake. Innocent bystanders complained of headaches and dizziness; diners were put off their food by its near-toxic intensity. It was banned in some American restaurants, where signs read ‘No Smoking. No Poison.’

Perfume is an ambiguous object, forever hovering on the edge of stink: what smells suave to me can be noxious to you, and the padded-shouldered juices of the 80s gave the first ammunition to the anti-perfume movement. Google ‘perfume + poison’ today and you’re just as likely to find entries about Dior as exposés on the purported toxicity of fragrance. Perfume aversion is no longer fuelled by the strength of the smell of perfume but by fear of the invisible chemicals that might be infiltrating our bodies through our skin and lungs. Activist groups have been flooding the internet with ominous warnings about ‘unlisted ingredients’ which sound as if they belong in some mad scientist’s lethal cocktail and would be enough to put off anyone but the staunchest fragrance aficionado. And since perfume, unlike anthrax, radiation, or the toxins in building materials, food and water, is both perceptible and dispensable, it’s crystallized a rampant paranoia. If you start obsessing that the woman in the next cubicle is poisoning you with her Obsession, at least you can do something about it: file a lawsuit.

But the fear of smells itself, brilliantly explored by the French historian Alain Corbin in his 1982 classic The Foul and the Fragrant, goes back millennia. Until the link between germs and disease was established in the late 19th century, people were convinced smells could kill. As far back as the 5th century AD, physicians were accusing foul odours of causing plagues. Since nobody knew how illnesses spread, it seemed logical to suspect the airborne stench rising from graveyards, charnels, open cesspools or stinky swamps. And no less logical to suppose that the stench, and hence the disease it carried, could be repelled by another, stronger smell. Aromatic materials were not only considered salubrious because of their medicinal properties: they were also believed to be the very opposite of the corruptible animal and vegetal matters whose putrescence was thought to cause disease. In fact, they were just about as pure as earthly matter could be, since aromatic resins burned without residue, and essential oils were the volatile spirit that remained after the distillation of plants. Those very same aromatic materials were used to prevent corpses from putrefying. Could they not prevent the corruption of the living body by disease as well?

So ‘plague doctors’ stuffed them in beak-shaped masks as they made their rounds during epidemics of the Black Death; aromatic materials were burned in houses, churches, streets and hospitals. And if the wealthy lavishly scented their clothes and held pomanders to their noses, it wasn’t only to cover up the effluvia of the great unwashed or the stench of cities and palaces: scent was their invisible armour against the Reaper. In fact, if everyone from kings to paupers did give off quite a pungent aroma from the late 15th century, when public baths were shut down for moral reasons (they often harboured prostitutes), until the late 18th century, it was precisely because foul miasmas were believed to carry disease. Physicians were convinced that water distended the fibres of the body, leaving it wide open to airborne contamination. Therefore, bathing was undertaken only under strict medical supervision, and people who’d just bathed were advised to stay under wraps for hours, if not days, until their bodies had sufficiently recovered to withstand exposure. Such cleanliness as there was came from washing face, teeth and hands with various cosmetic preparations; bodily grime was meant to be absorbed by white linen shirts, which only the upper classes could afford to change daily.

But the very notion that perfume had curative or protective properties implied that it could have the reverse effect, at least potentially. In Ancient Greece, the word pharmakon, from which ‘pharmacy’ is derived, designated both the poison and the remedy. If aromatic essences could act on the body by penetrating through the nose or skin, they might also kill. Odours are invisible: unlike poisonous foods which you can choose not to eat if you suspect something is amiss, you can’t defend yourself against them – you can’t hold your breath forever. And strong, apparently pleasant fragrances could very well conceal subtle poisons.

In the midst of the religious war that tore France apart in the late 16th century, the Catholic Queen Catherine de’ Medici was thus suspected of having assassinated the Protestant Jeanne d’Albret, Queen of Navarre, with a pair of poisoned gloves made by her perfumer Renato the Florentine. Though unfounded (Queen Jeanne died of tuberculosis), the accusation gives an indication of the ambivalent properties attributed to perfume. Even natural fragrances were suspicious. In 1632, in a clear-cut case of collective hysteria, the nuns of a convent in Loudun accused the priest Urbain Grandier of having cast a spell on them: the first to be ‘possessed’ by the charismatic Grandier claimed she had been bewitched by the smell of a bouquet of musk roses. Grandier was burned at the stake for witchcraft.

By the middle of the 18th century, some of the very aromatic materials that had been considered both exquisite and prophylactic were being condemned. Substances of animal origin such as musk, civet and ambergris were lumped in with putrid matters through medical anathema. The smell of musk, for instance, was compared to that of manure or fermented human excrement. Its very strength unsettled ‘our more delicate nerves’, wrote Diderot and d’Alembert in their Encyclopaedia in 1765. As the upper classes renewed their acquaintance with water and came to enjoy light, vegetal scents such as the eau de Cologne, wearing heady animalic concoctions became the sign not only of doubtful hygiene but of depraved tastes, fit only for skanky old libertines and their whores.

Perfume would remain a remedy until 1810, when Napoleon decreed separate statuses for perfumers and pharmacists: since the latter were compelled to disclose the composition of their preparations, the former chose to relinquish any medicinal claims to preserve their trade secrets. But perfumers never completely shook off the ambivalence of the original pharmakon … No wonder a perfume-phobic pharmacologist’s daughter ended up sticking her nose in it.

If I wanted further proof that perfume is indeed toxic, I’d filch my dad’s old lab coat to analyse the 1999 Hypnotic Poison, whose red bottle contains the antidote to the green one I was given over twenty years ago: Snow White’s poisoned apple, ripe and fit at last for a grown woman.

Was the perfumer Annick Menardo aware of what she was doing when she stuck an almond note into its jasmine sambac, musk and vanilla accords? As any reader of classic English murder mysteries knows, you can tell whether a victim has been poisoned with cyanide from the lingering smell of bitter almonds. In fact, like apple seeds or peach and cherry pits, the bitter almond contains a highly poisonous substance, amygdalin, which in turn contains sugar and benzaldehyde, a common aromatic ingredient that smells like amaretto liqueur, but can also yield cyanide. And thus, Hypnotic literally reeks of poison disguised as a delicacy, its toxicity betrayed by the slight bitterness of caraway seeds rising from a powdery cloud …

I’d long wanted to ask Menardo about that almond note, and lay my love at her feet for what must surely be one of the weirdest scents to come out in a mainstream brand, Bulgari Black. When I wear Black, I feel that I’ve either a) dropped my liquorice macaroon in my cup of lapsang souchong, b) powdered my butt with fancy talcum and slipped on my rubber bondage skirt, c) crossed a tough neighbourhood where someone’s been burning tyres in a cab that’s got one of those little vanilla-scented trees dangling from the rear-view mirror, or d) been guzzling the world’s peatiest single malt whisky and gargled with Shalimar to hide the fact.

But getting in touch with the brilliantly gifted Menardo was a daunting task. Perfumers working for big companies are much less accessible than independents like Bertrand Duchaufour. You can’t just cold-call them – least of all Menardo, who is famously reticent and uncompromising. Every time I brought her name up, insiders would wish me luck. And I did get lucky: while visiting the offices of Firmenich, where she works, I bumped into her in a corridor, a tiny bristling dark-haired sprite in a hot-pink top. It seemed awkward to spring my question about almonds – how pleasant can it be to be waylaid by some strange woman on your way to a meeting or to the loo? So after gushing about Bulgari Black (she gruffly responded, ‘But that’s old stuff!’), I let her go, contacted her again through email, and we made a phone appointment so that I could ask her about Hypnotic Poison.

So: did she work in the almond note on purpose? She chuckles.

‘I didn’t psychoanalyse myself. It’s possible.’

She explains she worked on the idea of toxicity by playing on the strength of the smell: ‘I knew I had to do something that was meaner than Poison.’

I point out to Annick that the apple seems to be a leitmotif in her career: another one of her best-sellers, the anise and violet Lolita Lempicka, which came out the same year as Hypnotic Poison, is also packaged in an apple-shaped bottle. She answers that apple itself is one of her fetish notes – a fond memory of a shampoo she used as a teenager, Prairial – so she sticks it in wherever she can. By this time we’re chatting away quite happily, and I confide the story of Geneviève’s poisoned parting gift.

‘Green Apple? Hey, I wore that too when I was a kid!’

My phone almost drops from my hand. The formidable little witch who whipped up my antidote to Green Apple actually wore it herself. There are no coincidences with perfume: it’s all black magic.

6

Despite my admiration for the cavity-inducing Hypnotic Poison, olfactory pastries were never something I could get particularly worked up about. I may want to offer myself up at dessert when the mood strikes; I don’t want to smell of it. Which is why Bertrand Duchaufour’s take on vanilla delights me particularly: it reminds me of something I’d much rather wrap my lips around after dinner than a spoonful of vanilla ice cream … a good cigar.

Surprised? Yes, the vanilla pod, as opposed to the synthetic vanillin more frequently used in fragrances and desserts, does have a tobacco facet, and that’s what Bertrand has chosen to underline, down to the slight vegetal mustiness of cured tobacco leaves. This is one of the things I find most intriguing about his style: the way he slips in weird notes that mess up the prettiness of a scent. For instance, the quasi-surrealistic way he grows a Cuban cigar out of a vanilla pod, as though that had been the pod’s subconscious desire all along.

Bertrand’s been making good on his promise: this is my third lesson in three weeks. Today I’ve asked him to explain the structure of one of his compositions so that I can re-enact the demonstration in my London course: I’m making good on my promise too, since I told him I’d include his work in the syllabus. I’d be a fool not to. After all, the man is one of the most distinctive perfumers in the business, one of the few who has enough artistic liberty to develop a consistent oeuvre and to impose his vision on the projects he takes on.

It took balls to stake that claim. He had to break out of a system that was set up in the late 30s and still dominates the industry, similar in its set-up to the system of the classic Hollywood era, with directors on the payroll of studios and forced to work within their constraints. Like the overwhelming majority of his colleagues, Bertrand was thus employed by Symrise, one of the big labs that produce aromatic materials and compositions.

He’d wanted to be a perfumer since the age of sixteen, when a girlfriend introduced him to Chanel N°19, but he’d been advised to skip the Versailles perfumery school and get an internship in Grasse. As he had no contacts there, he gave up, convinced he’d never become a perfumer. After studying biochemistry in Marseilles, he took a gap-year to tramp around South America before coming back to France to study for a degree in genetics. It was then he learned that a friend of his had won the coveted internship in Grasse: at last, he’d found the contact he needed. He got one too, stayed on, and ended up in the Paris branch of the company, where he was mentored by Jean-Louis Sieuzac, who authored such best-sellers as Opium for Yves Saint Laurent, Dune and Fahrenheit for Christian Dior or Jungle Elephant for Kenzo. In time, he made his way up to senior perfumer.

Being a perfumer on the payroll of a big lab can be a thankless job. Fine fragrances are the most prestigious gigs but, more often than not, you’re put to work on functional fragrances, the stuff that goes into detergents, cosmetics or hygiene products, which is where the big money is because of the volumes involved. It’s technically challenging and it can be aesthetically gratifying – just smell Ajax Spring Flowers and tell me if it’s not as good as some of the juices that are sold in department stores – but it’s certainly not glamorous.

Fine fragrance perfumers don’t necessarily get much more wiggle room because of the way the system is set up. It goes like this: the client, usually a designer brand, wants to put out a new fragrance. The brand’s marketing team comes up with the name, the bottle design and the concept for an ad campaign before anyone remembers that something actually needs to go into that bottle. A brief specifying the style, target market and cost of the product is knocked together and handed out to several competing labs. The staff perfumers who are interested in the project must come up with proposals, usually within a matter of a few weeks. The budget rarely goes over sixty to eighty euros per kilo of oil (the blend of aromatic materials to which alcohol will later be added). By way of comparison, the price per kilo for niche perfumes can shoot up to four hundred or even six hundred euros, but what actually ends up in a department-store bottle is worth less than ten euros. The labs present their proposals, which they develop on spec. The client selects one. The perfumer goes back to the lab to tweak it; sometimes several team up to accelerate the process. If it is a big project, the product is tested on consumer panels, after which it is tweaked some more, often until every original molecule has been blasted out of its body. If sales don’t do well, it may be tweaked again.

The system is hardly conducive to creativity. Perfumers learn to do compositions that test well in order to win the brief: after all, they’ve been hired to make money for their employers. What tests well is what consumers are familiar with. What consumers are familiar with are either best-selling fragrances or everyday products like shower gels, fabric softeners and shampoos. Recipes that sell well get around from one perfumer to another and from one company to another; they are recycled endlessly, so that you find the same accords in every fragrance. The same twenty to thirty raw materials are used over and over, out of the thousands that exist. On top of that, the systematic use of gas chromatography, a method that allows companies to analyse the competition’s products, has led to a practice called the ‘remix’: take current best-sellers, cut and paste, and you’ll have the next designer-brand juice. Another practice is called the ‘twist’: take a best-seller, change a couple of things in it and presto! Pour it into a bottle. If you ever wondered why everything smells the same in department stores, now you know.

Like so many of his colleagues, Bertrand became a perfumer because he was fascinated by the classics. The market forced him to go in another direction, though from the late 90s onwards he was lucky enough to work with people who did value originality and afforded him an opportunity to develop his distinctive style. But he was too much of a maverick to fit into the ‘studio system’ for ever, which is why he and his employers eventually decided to part ways by common accord.

‘I was asked to do things that didn’t interest me and I had a lot of trouble coming up with a decent product both for the company and for the brand.’

‘So I guess you weren’t offered a lot of stuff to do …’

‘I wasn’t offered anything any more.’

‘Because you were difficult?’

‘Because I told them to bugger off.’

‘In other words, you were a pain in the ass.’

‘I was a pain in the ass, that you can be sure of!’ he chuckles.

I’m quite sure Bertrand can be a pain in the ass, and I can readily envision his temper flaring up if he’s prodded too hard. That’s why I’m a little wary of asking him if he was serious when he said my story would make a great perfume. What if he brushes me off? I’m hoping he’ll bring the subject up himself, but right now he’s busy playing show-and-tell with vanilla absolute, talking me through its facets in a gleeful, earnest voice, as though he were rediscovering it all over again. Vanilla has animal, leathery and smoky facets, he enthuses; it also has woody, ambery, spicy and balsamic facets, and even unpleasant medicinal notes. That’s what he wanted to get at: to draw out every aspect of the vanilla pod.

In the scent, the vanilla acts as the core of a star-shaped structure. Its different facets are picked up and amplified by the other materials, to form a second, phantom vanilla; an olfactory illusion sheathing the real thing; a space in which all the notes resonate.

As Bertrand speaks, I scribble a diagram with vanilla as the ‘sun’ and the other materials as ‘planets’: rum, orange, davana (fruity, boozy), immortelle (walnut, curry, maple syrup, burnt sugar), tonka bean (hay, tobacco, almond, honey) and narcissus (hay, horse, green/wet, floral). Pretty soon Bertrand is scribbling in my notebook too, writing down the effects conjured when the different materials meet. For instance, rum and immortelle emphasize the woody/ambery facets: because rum is aged in oak casks, it already has a vanilla flavour imparted by the oak (vanillin can be synthesized from by-products of the wood industry). It all ties in: the sheer logic of it is limpid.

Bertrand’s compositions are not only impeccably intelligent, but also a reflection on the art of perfumery: in this case, exploring vanilla as though it were a strange new material and deducing its place on the scent-map. The beauty of them is that they also tell a story. Think of vanilla and you’re already in Central America, from where the plant originates. From there it’s only a short slide to the Caribbean islands and two of their chief luxury exports, cigars and rum, both of which share common facets with the vanilla pod. Again: logical.

But if the fragrance is a thinking woman’s (or man’s) vanilla because of the new light it sheds on the genre, it’s also a sultry, Carmen-rolling-cigars-on-her-thighs scent. Is it useful at this point to mention that the very word ‘vanilla’ comes from the Latin for ‘sheath’, vaina? Just add that missing letter – the erotic subtext is part of vanilla’s appeal. Not to mention that, despite what Freud once quipped, a cigar is not necessarily always a cigar …

This is what’s been making Bertrand’s work so interesting of late: the feeling that he has been engaging more sensuously with his materials. His scents used to be fascinatingly weird, dark and austere, as though he were making a point of holding at arm’s length the more pleasing aspects of perfumery. But his latest stuff has been getting hot and bothered, languorous and dirty; it’s growing flesh. He says it’s because, since he’s set up as an independent, he has a more hands-on relationship with his materials – in his old job, he wrote down his formulas and an assistant blended them – but also because he is now allotted larger budgets and can use higher quantities of the better, richer stuff. Yet I’m not quite sure it’s only that. His perfumes still have quirky notes, but they’re … more pleasing. More wearable.

‘More commercial, you mean? Well, maybe now that I’m independent I feel more responsibility …’

That’s not what I mean. To me, it’s as though at this stage of his career, he doesn’t feel as much of a need to go for the weird. As though he can allow himself to play with more outrightly seductive notes without having the feeling he’s selling out …

That stumps him a bit. He knits his bushy eyebrows.

‘Maybe. I don’t know.’

He can afford to stray out of his own weird comfort zone, I tell him. After all, he’s one of the best perfumers of his generation. At that, he blushes deeply, cocks his head, mutters the Gallic equivalent of ‘Aw, c’mon’, and gives a little kick to the tip of my boot while staring at his own. Now it’s my turn to squirm on my chair. I’m no Coco Chanel, though I don’t like roses much either. I don’t care about launching another N°5. But, like Chanel, I know what I want, and now’s the time to ask for it.

‘So, remember that story I told you about Seville? You said it would make a good perfume …’ At that point, I’m loath to confess, I consider leaning forward a bit to flash some cleavage – a tactic which, I’ve learned during my years as a journalist, quite efficiently throws male interviewees off their stride. It’s an urge I curb. ‘… does that mean you might want to go ahead and make it?’

He pauses, nods and looks me straight in the eye.

‘OK. I’m game. Let’s do it.’

And that would just about be when I faint.

7