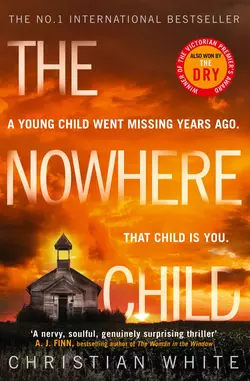

The Nowhere Child: The bestselling debut psychological thriller you need to read in 2019

Christian White

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1241.52 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A little girl went missing years ago. That child is you.A dark and gripping debut psychological thriller that won the 2017 Victorian Premier’s Literary Award, previously won by THE DRY and THE ROSIE PROJECT.‘Read page one, and you won’t stop. Guaranteed’ Jeffery DeaverA child was stolen twenty years agoLittle Sammy Went vanishes from her home in Manson, Kentucky – an event that devastates her family and tears apart the town’s deeply religious community.And somehow that missing girl is youKim Leamy, an Australian photographer, is approached by a stranger who turns her world upside down – he claims she is the kidnapped Sammy and that everything she knows about herself is based on a lie.How far will you go to uncover the truth?In search of answers, Kim returns to the remote town of Sammy’s childhood to face up to the ghosts of her early life. But the deeper she digs into her family background the more secrets she uncovers… And the closer she gets to confronting the trauma of her dark and twisted past.