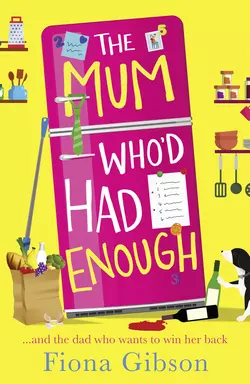

The Mum Who’d Had Enough: A laugh out loud romantic comedy perfect for fans of Why Mummy Drinks

Fiona Gibson

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 384.72 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 17.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The voice of modern women is back! Perfect for fans of Milly Johnson and Carole Matthews.‘More than funny, it’s true!’ ElleAfter sixteen years of marriage, Nate and Sinead Turner have a nice life. They like their jobs, they like their house and they love their son Flynn. Yes, it’s a very nice life.Or, at least Nate thinks so. Until, one morning, he wakes to find Sinead gone and a note lying on the kitchen table listing all the things he does wrong or doesn’t do at all.Nate needs to show Sinead he can be a better husband – fast. But as he works through Sinead’s list, his life changes in unexpected ways. And he starts to wonder whether he wants them to go back to normal after all. Could there be more to life than nice?