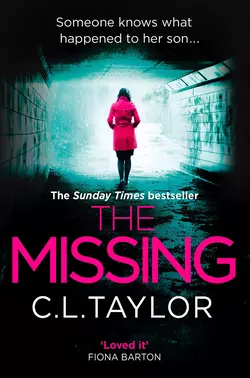

The Missing: The gripping psychological thriller that’s got everyone talking...

C.L. Taylor

‘The Missing has a delicious sense of foreboding from the first page, luring us into the heart of a family with terrible secrets and making us wait, with pounding hearts for the final, agonizing twist. Loved it’Fiona Barton, Author of THE WIDOWYou love your family. They make you feel safe. You trust them.But should you…?‘A twisty-turny psychological thriller … Well-written, pacy and gripping’ FabulousWhen fifteen-year-old Billy Wilkinson goes missing in the middle of the night, his mother, Claire, blames herself. She's not the only one. There isn't a single member of Billy's family that doesn't feel guilty. But the Wilkinsons are so used to keeping secrets from one another that it isn't until six months later, after an appeal for information goes horribly wrong, that the truth begins to surface.Claire is sure of two things – that Billy is still alive and that her friends and family had nothing to do with his disappearance.A mother's instinct is never wrong. Or is it?Sometimes those closest to us are the ones with the most to hide…"I was grabbed by this book from the first page and read the ending with an open mouth. I wish I could unread it so that I could go back and discover it again. Brilliant!"Angela Marsons, Author of SILENT SCREAM

C.L. TAYLOR

The Missing

Copyright (#uba854c0e-7c42-5a6f-8bbc-08ba4ba5775e)

Published by Avon

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins 2016

Copyright © C.L. Taylor 2016

Cover illustration © Henry Steadman 2016

C.L. Taylor asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008118051

Ebook Edition © April 2016 ISBN: 9780008118068

Version: 2018-06-21

Praise for The Missing (#uba854c0e-7c42-5a6f-8bbc-08ba4ba5775e)

‘Black Narcissus for the Facebook generation, a clever exploration of how petty jealousies and misunderstandings can unravel even the tightest of friendships. Claustrophobic, tense and thrilling, a thrill-ride of a novel that keeps you guessing.’

Elizabeth Haynes

‘A gripping and disturbing psychological thriller: every bit as good as The Accident.’

Clare Mackintosh

‘Fast-paced, tense and atmospheric, a guaranteed bestseller.’

Mark Edwards

‘Haunting and heart-stoppingly creepy, The Lie is a gripping roller coaster of suspense.’

Sunday Express

‘5/5 stars – Spine-chilling!’

Woman magazine

‘An excellent psychological thriller.’

Heat magazine

‘Packed with twists and turns, this brilliantly tense thriller will get your blood pumping.’

Claire Frost, Fabulous magazine

‘A real page-turner, with two story lines: one of growing menace in the present, and a past narrative of a girls-only holiday that goes horrifically wrong. Creepy, horrifying and twisty. C.L. Taylor is extremely good at writing stories in which you have no idea which characters you can trust, and the result is intriguing and scary and extremely gripping.’

Julie Cohen, 2014 Richard and Judy Summer Book Club Pick

‘The Lie is absolutely brilliant – The Beach, only darker, more thrilling and more tense. It’s the story of a twisted, distorted friendship. It’s a compelling, addictive and wonderfully written tale. Can’t recommend it enough.’

Louise Douglas

‘C.L. Taylor delivers another compelling read that’ll keep you turning pages way too late into the night. Warning: may cause drowsiness the following day.’

Tamar Cohen

‘My heart was racing after I finished C.L. Taylor’s brilliant new book The Lie. Dark, creepy and full of twists. I loved it.’

Rowan Coleman

‘C.L. Taylor is fast becoming the queen of psychological suspense. Read this: you won’t be disappointed.’

Victoria Fox

Dedication (#uba854c0e-7c42-5a6f-8bbc-08ba4ba5775e)

To my late grandmothers Milbrough Griffiths and Olivia Bella Taylor.

Table of Contents

Cover (#u9ea1197f-1773-5a45-8ddb-b760f9ef2528)

Title Page (#u9ed16cc8-4a34-5e3a-82fb-02fb29affe33)

Copyright (#ueff40d18-6a1a-53a7-b185-d02e55075345)

Praise for The Missing (#ub32bec5a-c812-54b8-9dbf-e3770700045d)

Dedication (#uafd24bdb-0aa8-5e20-8f08-01753f87d659)

Thursday 5th February 2015 (#ua9f52b43-5912-56cc-8283-2bc28a6b66ca)

Chapter 1 (#u48686ad1-d1d6-5ead-b69e-92787696a2eb)

Chapter 2 (#u93fb04e8-63a9-57d1-8627-b036a0d01f81)

Chapter 3 (#u58a2947d-8d56-5a69-8aa2-413c560ebc36)

Chapter 4 (#ufdac0dd7-b4ef-548a-8c3e-b52d04efc961)

Chapter 5 (#ua3f830b3-c4c9-58ca-9bcb-be3e9751b6aa)

Monday 11th August 2014 (#u5661cc9c-2d9c-5117-bd6c-3f457dab5c10)

Chapter 6 (#u787c1f43-7bd8-51d3-bb91-2d319a4421a8)

Chapter 7 (#u2ff8c419-7cc3-5211-9c12-7c645ab565fe)

Chapter 8 (#u67b8cf47-128d-51b9-a251-a0962a1aba23)

Friday 22nd August 2014 (#u153b0811-fbe5-5137-8848-184a2a12c95d)

Chapter 9 (#u458d3aad-b6a7-594e-89f8-6d969c2c2571)

Chapter 10 (#u83ab6820-19b1-59d9-bd4d-70e31aa6a452)

Chapter 11 (#uebeb948d-c900-5520-8f42-cda27aa25b60)

Tuesday 26th August 2014 (#u121729c7-a993-596b-a117-8167b84d91bc)

Chapter 12 (#ub524609b-8f7e-5450-a264-85b0d9535b44)

Chapter 13 (#uda8ccdfa-e5ff-506f-91e8-e028e922439e)

Thursday 25th September 2014 (#uea97b398-aec4-5ff2-abc8-36fc7f738e0b)

Chapter 14 (#u1ac3fef1-ae8a-5077-857f-27dbdd045cfa)

Chapter 15 (#u54b9e2d1-c482-5cb7-864e-310a9728a88a)

Chapter 16 (#uf74cbf54-4826-5e50-9f09-fbd8d73e3d31)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday 7th October 2014 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Wednesday 8th October 2014 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 10th October 2014 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 24th October 2014 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday 3rd November 2014 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday 4th November 2014 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday 8th November 2014 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday 25th November 2014 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40 (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday 27th November 2014 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43 (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 19th December 2014 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 44 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 45 (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 2nd January 2015 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 46 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 47 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 48 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 49 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 50 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 51 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 52 (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday 3rd January 2015 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 53 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 54 (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 16th January 2015 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 55 (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday 27th January 2015 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 56 (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday 27th January 2015 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 57 (#litres_trial_promo)

Wednesday 28th January 2015 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 58 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 59 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 60 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 61 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 62 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 63 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 64 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 65 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 66 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 67 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 68 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 69 (#litres_trial_promo)

A conversation with C.L. Taylor (#litres_trial_promo)

Book club questions for The Missing by C.L. Taylor (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Author Note (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by C.L. Taylor (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

(#uba854c0e-7c42-5a6f-8bbc-08ba4ba5775e)

Thursday 5th February 2015 (#uba854c0e-7c42-5a6f-8bbc-08ba4ba5775e)

Jackdaw44: Do you want to play a game?

ICE9: No.

Jackdaw44: Not sex.

ICE9: What then?

Jackdaw44: Questions. I’m bored. It’s just a bit of fun.

ICE9: …

Jackdaw44: I take it that’s a yes. OK. First question. Would you rather go deaf or blind?

ICE9: You really are bored, aren’t you? Deaf.

Jackdaw44: Would you rather drown in a river or burn in a fire?

ICE9: Neither.

Jackdaw44: You have to choose.

ICE9: Drown in a river.

Jackdaw44: Be buried or cremated?

ICE9: I don’t like this game.

Jackdaw44: It doesn’t mean anything. I’m just trying to get to know you better.

ICE9: Weird way of doing it.

Jackdaw44: I love you. I want to know everything about you.

ICE9: Buried.

Jackdaw44: Be infamous or be forgotten?

ICE9: Forgotten.

Jackdaw44: Seriously???

ICE9: Yes.

Jackdaw44: I’d choose infamy every time.

ICE9: No surprise there.

Jackdaw44: Cry at my funeral or save your tears for private?

ICE9: WHAT?!! Stop being so morbid.

Jackdaw44: I’m not. I’m just preparing you.

ICE9: For what?

ICE9: Hello?

ICE9: HELLO?

Chapter 1 (#uba854c0e-7c42-5a6f-8bbc-08ba4ba5775e)

Wednesday 5th August 2015

What do you wear when you peer into the barrel of a camera and plead for someone, anyone, to please, please tell you where your child is? A blouse? A jumper? Armour?

Today is the day of the second television appeal. It’s been six months since my son disappeared. Six months? How can it be that long? The counsellor I started seeing four weeks after he was taken from us told me the pain would lessen, that I would never feel his loss as keenly as I did that first day.

She lied.

It takes me the best part of an hour before I can look at myself in the bedroom mirror without crying. My hair, cut in a short elfin style last week, doesn’t suit my wide, angular face and my eyes look dark and deep-set beneath the new fringe. The blouse I’d deemed sensible and presentable last night suddenly looks thin and cheap, the knee-length pencil skirt too tight on my hips. I select a pair of navy trousers and a soft grey jumper instead. Smart, but not too smart, serious but not sombre.

Mark is not in the bedroom with me. He got up at 5.37 a.m. and slipped silently out of the room without acknowledging my soft grunt as I peered at the time on the alarm clock. When we went to bed last night we lay in silence side by side, not touching, too tense to talk. It took a long time for sleep to come.

I didn’t say anything when Mark got up. He’s always been an early riser and enjoys a solitary hour or so, pottering around the house, before everyone else wakes up.

Our house was always so noisy in the morning, with Billy and Jake fighting over who got to use the bathroom first and then turning up their stereos full volume when they returned to their rooms to get changed. I’d pound on their bedroom doors and shout at them to turn the music down. Mark’s never been very good with noise. He spends hours each week driving from city to city as part of his job as a pharmaceutical sales rep but always in silence – no music, audiobooks or radio for him.

‘Mark?’ It’s 7.30 a.m. when I pad into the kitchen, taking care to step over the cracked tile by the fridge so I don’t snag my pop socks. Three years ago Billy opened the fridge and a bottle of wine fell out, cracking the tiles that Mark had only finished laying the day before. I told him it was my fault.

‘Mark?’

The kettle is still warm but there’s no sign of my husband. I poke my head around the living-room door but he’s not there either. I return to the kitchen, and open the back door that leads to the driveway at the side of the house. The garage door is open. The rrr-rrr-rrr splutter of the lawnmower being started drifts towards me.

‘Mark?’ I slip my feet into a pair of Jake’s size ten trainers that have been abandoned next to the mat and slip-slide across the driveway towards the garage. It’s August and the sun is already high in the sky, the park on the other side of the street is a riot of colour and our lawn is damp with dew. ‘You’re not planning on cutting the grass now, surel—’

I stop short at the garage door. My tall, fair-haired husband is bent over the lawnmower in his best navy suit, a greasy black oil stain just above the knee of his left trouser leg.

‘Mark! What the hell are you doing?’

He doesn’t look up.

‘Servicing the lawnmower.’ He gives the starting cord another yank and the machine growls in protest.

‘Now?’

‘I haven’t used it for a month. It’ll rust up if it’s not serviced.’

I don’t know whether to laugh or cry.

‘But Mark, it’s Billy’s appeal.’

‘I know what day it is.’ This time he does look up. His cheeks are flushed and there’s a sheen of sweat that stretches from his thick, unkempt eyebrows all the way up to his receding hairline. He passes a hand over his brow, then wipes it on his trouser leg, rubbing sweat into the greasy oil stain. I want to scream at him that he’s ruined his best suit and he can’t go to Billy’s appeal like that, but today isn’t the day for an argument, so I take a deep breath instead.

‘It’s seven-thirty,’ I say. ‘We need to get going in half an hour. DS Forbes said he’d meet us at eight-thirty to go through a few things.’

Mark rubs a clenched fist against his lower back as he straightens up. ‘Is Jake ready?’

‘I don’t think so. His door was shut as I came downstairs and I couldn’t hear voices.’

Jake shares his bedroom with his girlfriend Kira. They started dating at school when they were sixteen and they’ve been together three years now, sharing a room in our house for the last eighteen months. Jake begged me to let her stay. Her mum’s drinking had got worse and she’d started lashing out at Kira, physically and verbally. He told me that if I didn’t let her live with us she’d have to move up to Edinburgh to live with her grandfather and they’d never get to see each other.

‘Well, if Jake can’t be bothered to get up, then let’s go without him,’ Mark says. ‘I haven’t got the energy to deal with him. Not today.’

It was Billy who used to disappoint Mark. Billy with his ‘I don’t give a shit’ attitude about school and his belief that life owed him fame and fortune. Jake was always Mark’s golden boy in comparison. He worked hard at school, gained six A- to C-grade GCSEs and passed his electrician course at college with flying colours. These days it’s phone calls about Jake’s poor attendance at work that we’re dealing with, not Billy’s.

I haven’t got the energy to deal with Jake either but I can’t just shrug my shoulders like Mark. We need to present a united front to the media. We all need to be there, sitting side by side behind the desk. A strong family, in appearance if nothing else.

‘I’m going back to the house. I’ll get your other suit out of the wardrobe,’ I say but Mark has already turned his attention back to the lawnmower.

I shuffle back to the path, Jake’s oversized shoes leaving a trail in the gravel, and reach for the handle of the back door.

I hear the scream the second I push it open.

(#ulink_b2a546ce-b194-50db-bfe0-06467d3b787a)

Chapter 2 (#ulink_b2a546ce-b194-50db-bfe0-06467d3b787a)

‘Jake, give me that!’ Kira’s screech carries down the stairs and there’s a loud thump from the bedroom above as something, or someone, hits the floor.

I kick off Jake’s shoes and take the stairs two at a time, cross the landing and fly into his bedroom without stopping to knock. There’s a flurry of activity as Kira and Jake jump away from each other. Barely five foot tall with blonde hair that falls past her shoulders, Kira looks tiny and doll-like in her pink knickers and a tight white T-shirt. Jake is bare-chested, naked apart from a pair of black jockey shorts that cling to his hips. His shoulders and chest are so broad and muscled he seems to fill the room. At his feet is a shattered bottle leaking pale brown liquid onto the beige carpet. There are shards of glass on the pile of weights plates beside it.

‘Mum!’ Jake leaps away from Kira, planting his right foot on the broken bottle. He howls in anguish as a shard of clear glass embeds itself in his sole.

‘Don’t!’ I shout, but he’s already yanked it out. Bright red blood gushes out, covering his fingers and dripping onto the carpet.

‘Don’t move!’ I sprint to the bathroom and grab the first towel I see. When I return to the bedroom Jake is sitting on the bed, one hand gripping his ankle, the other pressed over the wound. Blood seeps between his fingers. Kira, still standing in the centre of the room, is ashen. I pick my way carefully through the broken glass on the floor, then crouch on the carpet in front of Jake. It stinks of alcohol.

‘Let go.’

He winces as he peels his fingers away from his foot. The wound isn’t more than half a centimetre across but it’s deep and blood is still gushing out. I wrap the towel as tightly around it as I can in an attempt to stem the flow.

‘Hold it here.’ I gesture for Jake to press his hands over the towel. ‘I need to get a safety pin.’

Seconds later I’m back in the bedroom and attempting to secure the makeshift bandage around my son’s foot. There are dark circles under his eyes and the skin is pulled too tight over his cheekbones. Mark and I weren’t the only ones who didn’t sleep last night.

‘What happened, Jake?’ I ask carefully.

He looks past me to Kira who is pulling on some clothes. Her lips part and, for a second, I think she’s about to speak but then she lowers her eyes and wriggles into her jeans. Downstairs the back door opens with a thud as Mark makes his way back into the house, then there’s a click-click sound as he paces backwards and forwards on the kitchen tiles. In a minute he’ll be up the stairs, asking what the hold-up is.

I sniff at Jake. His breath smells pungent. ‘Were you drinking that rum before I came in?’

‘Mum!’

‘Well? Were you?’

‘I had a few last night, that’s all.’

‘And then some.’ I pluck a large piece of glass from the carpet. Most of the label is still affixed. ‘What the hell were you thinking?’

‘I’m stressed, okay?’

‘I haven’t got enough for a taxi,’ Kira says plaintively, reaching into her jeans pocket and proffering a palm of small change.

‘Claire?’ Mark’s voice booms up the stairs. ‘It’s eight o’clock. We have to go. Now!’

‘I need to leave,’ Kira says. ‘There’s a college trip to London today – we’re going to the National Portrait Gallery – and I’m supposed to be at the train station for half eight.’

‘Okay, okay.’ I gesture for her to stop panicking. ‘Give me a sec.’

‘Mark?’ I step out onto the landing and shout down the stairs. ‘Have you got any cash on you?’

‘About three quid,’ he shouts back. ‘Why?’

‘Doesn’t matter.’

‘Right.’ I step back into Jake’s bedroom. ‘Kira, I’ll give you a lift to the train station. And as for you, Jake …’ There’s no blood on the towel I’ve pinned around his foot but he’ll still need the wound to be cleaned and a tetanus jab. If there was time I’d drop Kira at the station and then take Jake to the doctor’s but it would mean doubling back on myself and I can’t be late for the appeal. Why did this have to happen today of all days?

‘Okay.’ I make a snap decision. ‘Jake, stay here and sober up and I’ll drive you to the GP’s when I get back. If you need anything, Liz is next door. She’s not working until later.’

‘No, I’m coming with you. I need to go to the press conference.’ Jake grimaces as he pushes himself up and off the bed and hops onto his good foot so we’re face to face. Unlike Billy who shot up when he hit twelve, Jake’s height has never crept above five foot nine. The boys couldn’t have an argument without Billy slipping in some sly jab about his older brother’s stature. Jake would retaliate and then World War III would break out.

‘Claire!’ Mark shouts again, louder this time. He’ll fly off the handle if he sees the state Jake is in. ‘Claire! DS Forbes is here. We need to go!’

‘You’re not going anywhere,’ I hiss at Jake as Kira pulls an apologetic face and squeezes past me. She presses herself up against the linen cupboard on the landing, pulls on her coat and then roots around in the pockets.

‘Billy was my brother,’ Jake says. His face crumples and for a split second he looks like a child again, but then a tendon in his neck pulses and he raises his chin. ‘You can’t stop me from going.’

‘You’ve been drinking,’ I say as levelly as I can. ‘If you want to help Billy, then the best thing you can do right now is stay at home and sleep it off. We’ll talk when I get back.’

‘Claire!’ Mark shouts from the top of the stairs.

‘Mum …’ Jake reaches a hand towards me but I’m already halfway out the door. I yank it shut behind me, just as Mark draws level.

‘Is Jake ready?’

‘He’s not well.’ I press my palms against the door.

‘What’s wrong with him?’

‘Stomach upset,’ Kira says, her soft voice cutting through the awkward pause. ‘He was up all night with it. It must have been the vindaloo.’

I shoot her a grateful look. Poor girl, getting caught up in our family drama when the very reason she moved in with us was to escape from her own.

Mark glances at the closed door behind me, then his eyes meet mine. ‘Are we off then?’

‘I need to drop Kira at the train station for her college trip. You go on ahead with DS Forbes and I’ll meet you there.’

‘How’s that going to look? The two of us turning up separately?’ Mark looks at Kira. ‘Why didn’t you mention this trip last—’ He sighs. ‘Never mind. Forget it. I’ll see you there, Claire.’

He hasn’t changed his trousers. The greasy oil stain is still visible, a dark mark on his left thigh, but I haven’t got the heart to mention it.

(#ulink_d36a63d1-4925-5207-af29-35afe4686af0)

Chapter 3 (#ulink_d36a63d1-4925-5207-af29-35afe4686af0)

Neither of us say a word as we pile into the car and I start the engine. The silence continues past the Broadwalk shopping centre and down Wells Road. Only when I stop the car at the traffic lights by the Three Lamps junction and Kira pulls her iPod out of her jacket pocket do I speak.

‘What was that all about?’

‘Sorry?’ She looks at me in alarm, as though she’s forgotten I’m sitting next to her.

‘You and Jake, earlier.’

‘It was just …’ She stares at the red stop light as though willing it to change to green. Without her thick black eyeliner and generous dusting of bronzing powder her heart-shaped face looks pale and the sprinkle of freckles across her nose makes her look younger than she is. ‘Just … a thing … just an argument.’

‘It looked serious.’

‘It got a bit out of hand, that’s all.’

‘I’m guessing Jake didn’t go to bed last night.’

‘No. He didn’t.’

‘Oh God.’ I sigh heavily. ‘Now I’m even more worried about him.’

‘Are you?’

I feel a pang of pain at the surprise in her eyes. ‘Of course. He’s my son.’

‘He’s not Billy, though, is he?’

‘What’s that supposed to mean?’

‘Nothing. Sorry. I don’t know why I said that.’

I wait for her to say more but no words come. Instead she reaches into her handbag, pulls out a black eyeliner and flips down the sun visor. Her lips part as she draws a thick black ring around each eye, then dabs concealer on the raised, discoloured patch of skin near her right temple. It looks like the beginning of a bruise.

The red light turns amber, then green and I press on the accelerator.

Neither of us speaks for several minutes. I glance across at Kira, at the lump on her temple, and my stomach lurches.

‘Did Jake hit you?’

‘What?’

‘When you were fighting over the bottle. There’s a bruise on your head. Did he hit you?’

‘God, no!’

‘So how did you get the bruise?’

‘At the club last night.’ She flips down the visor and examines the side of her head in the mirror, prodding it appraisingly with her index finger. ‘I dropped my mobile and hit my head on the corner of the table when I bent down to get it.’

‘Kira, I know I’m not your mum but you’re the nearest thing I’ve got to a daughter and if I thought anyone was hurting you—’

She slaps the visor shut. ‘Jake didn’t hit me. All right? He’d never do something like that. I can’t believe you’d say something like that about your own son.’

I tighten my grip on the steering wheel.

‘Sorry,’ she says quickly. ‘I know you’re trying to look out for me but—’

‘Forget it.’ I slow the car as we approach the roundabout. ‘Just tell me one thing. How long has he been drinking in the mornings?’

She doesn’t reply.

‘Kira, how long?’

‘Just today. I think.’

‘You think?’ I can’t keep the incredulity out of my voice. They spend every waking minute together. How could she be unsure about something like that?

‘Yeah.’ She zips up her make-up bag and gazes out of the window as the car swings around the roundabout and we approach Bristol Temple Meads. As I indicate left and pull into the station and park the car, I can’t help but scan the small crowd of people milling around outside the station, smoking cigarettes and queuing for taxis. I can’t go anywhere without looking for Billy.

‘Do you think he’s got a drink problem?’

‘No.’ She shakes her head as she unbuckles her seat belt and opens the door. ‘He’s not an alcoholic, if that’s what you mean. He opened the rum when we got home from the club. He was wired and couldn’t sleep.’

‘Because of Billy’s appeal?’

‘Yeah.’ She lifts one leg out of the foot well, places it on the pavement outside and gazes longingly at the entrance to the train station.

‘Kira?’ I reach across the car and touch her on the shoulder. ‘Is there anything you want to talk to me about?’

‘No,’ she says. Then she jumps out of the car, handbag and make-up bag clutched to her chest, and sprints towards the station entrance before I can say another word.

(#ulink_0af6c45b-53fe-568c-8688-a37b286096ef)

Chapter 4 (#ulink_0af6c45b-53fe-568c-8688-a37b286096ef)

It’s a small conference room, tucked away in the basement of the town hall with a strip light buzzing overhead and no natural light. It’s a quarter of the size of the one where we made our first appeal for Billy, forty-eight hours after we reported him missing. Unlike that first appeal, when every single one of the plastic-backed chairs in the rows opposite us were filled, there are only half a dozen journalists and photographers present. Most of them are fiddling with their phones. They glance up as we file in with DS Forbes, then look back down again. A couple of them begin scribbling in their notebooks.

Mrs Wilkinson looks sombre in a pale grey jumper and trouser ensemble whilst Mr Wilkinson looks surly and distracted in a dark suit, the leg of his trousers stained with what looks like dirt or oil.

I have no idea if that’s what they’ve written. I’ll find out tomorrow, I imagine. I can’t bear to read the papers, particularly not the online versions with the horrible, judgemental comments at the bottom, but I know Mark will. He’ll pore over them, growling and swearing and mumbling about ‘the bloody idiot public’.

I didn’t know what a double-edged sword media attention would be back when Billy disappeared. I was desperate for them to publish our story – we both were, the more attention Billy’s story got the better – but I couldn’t have prepared myself for the barrage of speculation and judgement that came with it. I looked pale and distraught, those were the words most of the reporters used to describe me during that first press conference. Mark was described as cold and reserved. He wasn’t reserved – he was bloody terrified, we both were. But while I quaked, twisting my fingers together under the desk, Mark sat still, straight-backed, his hands on his knees and his eyes fixed on the large ornate clock on the opposite wall. At one point I reached for his hand and wrapped my fingers around his. He didn’t so much as glance at me until he’d delivered his appeal. At the time I felt desperately hurt but later, in the privacy of our living room, he explained that, as much as he’d wanted to comfort me, he hadn’t been able to.

‘You know I compartmentalize to deal with stress,’ he said. ‘And I needed to deliver my appeal without breaking down. If I’d have touched you, if I’d so much as looked at you I would have crumbled. And I couldn’t do that, not when what I had to say was so important. You can understand that. Can’t you?’

I could and I couldn’t, but I envied his ability to shut out the thoughts and feelings he didn’t want to deal with. My emotions can’t be shut into boxes in my head. They’re as tangled and jumbled as the strands of thread in the bottom of my grandmother’s embroidery basket. And the one thought that runs through everything, the strand that is wrapped around my heart is, Where is Billy?

‘Claire?’ DS Forbes says. ‘They’re ready for your statement now.’

A television camera has appeared in the aisle that runs between the lines of plastic-backed chairs. The lens is trained on my face. We decided some weeks ago that I should be the one to make this appeal.

‘The public respond more favourably when the mother does it,’ DS Forbes said. He made no mention of the horrible comments that had appeared online when Mark made the last appeal six months ago. Comments like: You can tell the father’s behind it. He’s not showing any emotion and I bet you money it was the dad. It always is.

‘Ready?’ DS Forbes says again and this time I sit up straighter in my chair and take a deep breath in through my nose. I can smell DS Forbes’s aftershave and the faintest scent of motor oil emanating from Mark, who’s sitting on the other side of me. I can sense him watching me, but I don’t turn to look at him before I pick up the prepared statement on the desk in front of me. I can do this. I no longer need a hand on my knee.

‘Six months ago today,’ I say, looking straight into the camera lens, ‘on Thursday the fifth of February, my younger son Billy disappeared from our home in Knowle, South Bristol, in the early hours of the morning. He was only fifteen. He took his schoolbag and his mobile phone and he was probably dressed in jeans, Nike trainers, a black Superdry jacket and an NYC baseball hat …’ I falter, aware that some of the journalists are twisting round in their seats, no longer scribbling in their notebooks. Mark, beside me, makes a low noise in the base of his throat and DS Forbes leans forward and puts his elbows on the desk. ‘We all miss Billy very much. His disappearance has left a hole in our family that nothing can fill and …’ I keep my eyes trained on the camera but I’m aware of a commotion at the back of the room. One man is wrestling with another in the doorway. ‘Billy, if you’re watching, please get in touch. We love you very, very much and nothing can change that. If you don’t want to ring us directly, please just walk into the nearest police station or get in touch with one of your friends.’

The producer standing next to the cameraman taps him on the shoulder and signals towards the back of the room. The camera twists away from me and a shout emanates from the doorway.

‘Get off me! I’ve got a right to be here! I’ve got a right to speak.’

(#ulink_85ec0d91-0887-55fc-9354-b5f4cc87b7d4)

Chapter 5 (#ulink_85ec0d91-0887-55fc-9354-b5f4cc87b7d4)

‘What’s Jake doing here?’ Mark stares over the heads of the journalists and several flash bulbs fire at once, lighting up the corner of the room where Jake is remonstrating with a male police officer. ‘I thought you said he was ill.’

‘He was … is. Let me deal with this.’

‘Mrs Wilkinson, wait!’ DS Forbes shouts as I hurry across the room and shoulder my way through the circle of journalists that has formed around my son. I can just about make out the back of Jake’s head. His fair hair is wild and tousled without a liberal application of hair gel. He disappears as a policeman steps in front of him, blocking my view.

‘Excuse me. Excuse me, please.’

The TV cameraman hisses as I push past him but he’s shushed by his producer. ‘That’s the mum, get her in shot.’

I push past a couple of council officials and approach the policeman who’s shepherding Jake towards the open doorway. Tapping him on the back of his black stab vest has no effect so instead I pull on his arm.

He doesn’t so much as glance at me. Instead he keeps his eyes trained on Jake; Jake, who’s a good six inches shorter, with his hands clenched at his sides and the tendons straining in his neck.

‘Please,’ I shout. ‘Please stop, he’s my son.’

‘Mum?’ Jake says and the police officer looks at me in surprise. He lowers his arms a fraction.

‘He’s my son,’ I say again.

The policeman glances behind me, towards the poster of Billy affixed to a flipchart beside the desk.

‘No, not Billy,’ I say. ‘This is Jake, my other son.’

‘Other son? I wasn’t told to expect any other relatives …’ He looks at DS Forbes who shakes his head.

‘It’s all right, PC George. I’ve got this.’

DS Forbes has met Jake before. He interviewed him at length, the day after Billy disappeared, just as he and his team interviewed all our extended family and friends.

‘Show’s over, guys.’ He signals to the producer to cut the filming and gestures for the journalists to return to their seats. No one moves.

‘Jake!’ A female journalist with a sharp blonde bob reaches a hand over my shoulder and waves a Dictaphone in my son’s direction. ‘What was it you wanted to say?’

‘Jake?’ The producer proffers a microphone. ‘Did you have a message for Billy?’

My son takes a step forward, shoulders back, chin up. He glances at PC George and raises an eyebrow, vindicated.

‘What happened to your foot, Jake?’

A short, balding man with hairy forearms that poke out of his rolled-up shirtsleeves points at Jake’s trainers. The instep of his right shoe, normally pristine and white, is muddied with brown blood.

‘Jake?’ Mark says.

The room grows quiet as my husband and son stare at each other. They’re waiting for Jake to speak. I wait too. I can feel Mark bristling behind me. This is his worst nightmare – our respectable, measured appeal transformed into a bar-room brawl.

I hear a click and a whirr from the camera to my left and I imagine the lens zooming in on Jake’s pale, drawn face. He passes the heel of his hand over his damp brow and then, with only the briefest of glances at me, turns on the heel of his good foot and limps out of the room.

(#ulink_6169af2a-b908-56ba-9a64-1279f9306618)

Monday 11th August 2014 (#ulink_6169af2a-b908-56ba-9a64-1279f9306618)

Jackdaw44: Fuck my life.

ICE9: Don’t say that.

Jackdaw44: Why not. It’s true. My dad is a hypocritical wanker and my mum is fucking clueless.

ICE9: Have you talked to your dad about the weekend?

Jackdaw44: Are you fucking kidding?

ICE9: You should give him the chance to explain.

Jackdaw44: What? That he’s weak, spineless, a liar and a lecherous bastard? No, thanks.

ICE9: Maybe it’s not how it seemed.

Jackdaw44: You’re taking the piss, right? You saw me. You saw what I did.

ICE9: That was stupid.

Jackdaw44: It was sick. I wish I’d seen the look on his face when he saw his car window. When he got home he told Mum that vandals did it. Ha. Ha. Ha. I’m the fucking vandal.

Jackdaw44: You still there?

ICE9: Yeah. Sorry. Bit busy.

Jackdaw44: No worries. Just wanted to say thanks for cooling me out. I would have totally lost my shit if you hadn’t turned up.

ICE9: You did lose your shit.

Jackdaw44: Could have been worse.

ICE9: Hmm.

Jackdaw44: Anyway. Thanx.

(#ulink_5cb43586-20a4-5326-bc3e-49d50aeb967a)

Chapter 6 (#ulink_5cb43586-20a4-5326-bc3e-49d50aeb967a)

‘What the hell were you thinking?’ Mark is standing in the centre of the living room with his arms crossed over his chest. He’s loosened his tie and popped the top button of his shirt. The skin at the base of his throat is mottled and red.

‘Sod this.’ Jake moves to get out of his armchair, wincing as he puts weight on his bad foot.

‘You’ll stay where you bloody are,’ Mark shouts and I grip the cushion I’m clutching to my chest a little tighter. ‘This is my house and as long as you live here you’ll do what I say.’

‘Yeah, because that worked out well with Billy, didn’t it?’ Jake doesn’t raise his voice but Mark stumbles backwards as though the question has been screamed in his face.

He seems to fold in on himself, then quickly recovers. ‘What did you just say?’

‘Forget it.’

‘No, say it again.’

‘Please!’ I say. ‘Please don’t do this.’

‘It’s all right, Mum,’ Jake says. ‘I can take Dad.’

‘Take me?’ Mark laughs. ‘Aren’t we the big man now we’ve grown a few muscles? Steroids making you brave, are they, son?’

I stare at Jake in horror. ‘You’re not taking steroids, are you?’

‘Dad doesn’t know what he’s talking about.’

‘One more word from you,’ Mark says, ‘and you’re out.’

‘Please!’ I say. ‘Please! Please stop! Mark, he’s your son! He’s your son.’

A tense silence fills the room, punctuated only by the sound of my own raggedy breathing. I brace myself for round two. Instead Mark’s shoulders slump and he exhales heavily.

‘Always the villain,’ he says, looking from me to Jake. ‘I’m always the villain.’

I want to say something. I want to contradict him. To support him. But to do so would mean choosing between my husband and my son. It’s like the night Billy disappeared all over again. My family is disintegrating in front of my eyes and there’s nothing I can do to stop it.

‘Mum,’ Jake says as the back door slams shut and Mark leaves the house. ‘I can explain.’

‘Later.’ My throat is so tight I can barely speak. ‘I’ll talk to you later.’

(#ulink_b76d61e3-7421-554b-9129-c4ed89265af0)

Chapter 7 (#ulink_b76d61e3-7421-554b-9129-c4ed89265af0)

‘Here you go.’ Liz places a steaming mug of tea on the table in front of me, then pulls out a chair and sits down. A split second later she stands up again, crosses the kitchen and rummages around in the back of a cupboard bursting with tins, jars and packets of pasta and rice. It’s the day after the appeal. I was going to pop in on Liz yesterday but, after everything that happened, I didn’t have the energy.

‘Ah! Knew I had some.’ She brandishes a 100-gram bar of Galaxy at me and returns to the table. ‘Hidden from Caleb and for emergencies only,’ she says as she sets it in front of me. ‘And days when I decide to skip Slimming World.’

‘I’m not hungry.’

‘Mind if I do then?’ She runs a nail along the gold wrapper and snaps off four pieces. She bites into the chocolate, takes a swig of tea, then smiles broadly. ‘That’s better. Caleb was in a pig of a mood this morning, whingeing about the lack of clean socks in his drawer. Hellooooo, we both work and you’re twenty. Wash your own bloody socks. I thought he’d make more of an effort with his personal hygiene now he’s met someone. Did I tell you about the new boyfriend?’

I shake my head.

‘He met him in a pub in Old Market. Eighteen, works in House of Fraser. I haven’t met him yet. Caleb said he doesn’t want to scare him off by introducing him to me. Cheeky shit. Anyway, sorry.’ She leans back in her chair and folds her arms across her chest. ‘How are you? I meant to watch the appeal but next door’s cat got into the garden again. It was primed to take a shit on the lawn so I chucked some water at it. I thought I’d pop in after you got back but I spotted Mark storming out the back door looking really pissed off and figured it wasn’t the best time.’

That’s the thing I love about Liz; Billy’s disappearance hasn’t changed our friendship in the slightest. Whilst everyone else awkwardly avoids the subject or cross-examines me about the latest developments Liz is just Liz. You crave normality after something terrible happens. Everything reminds you of what you’ve lost – everything – and sometimes you just want to stop thinking about it. I love hearing Liz bitch about Lloyd. I enjoy her little rants about her son Caleb or Elaine, her boss at the supermarket where she works.

Mark compartmentalizes his life. He has the ‘boxes’ in his head he escapes into. I don’t. But at least I have Liz.

‘So how was it?’ she asks.

‘Awful.’

I tell her about Kira screaming, the booze, the cut foot, Jake’s interruption and the argument when we all got home.

‘I’m just so tired,’ I say as she swipes a box of tissues from the windowsill and pushes them towards me. ‘I just want Billy to come home and for this to be over. I miss him, Liz. I miss him so much.’

‘I know,’ she says. ‘I know you do.’

I pull a tissue from the box and dab at my cheeks. I hate that my default emotional reaction is crying. I wish I could shout and scream or punch something instead.

‘Sorry,’ I say.

‘For what? If you can’t snot all over your best friend’s kitchen where can you?’

I try not to cry in front of Mark and Jake because I don’t want them to worry about me but it’s different with Liz. Her kitchen is a safe haven. We’ve known each other since Liz and Lloyd moved next door when the boys were little. They’d play in the back garden while Liz and I would sit on deckchairs and chat. It was a tentative friendship at first, as we sussed each other out, but it wasn’t long before we started taking it in turns to do the school run and the odd bit of babysitting. The first time we went out for drinks we got so drunk we stopped being polite and properly opened up. We were both in tears by the end of the night. Since then we’ve been there for each other through everything – Lloyd walking out on Liz last year, my father-in-law’s heart attack and now Billy.

‘What you going to do now then?’ she asks, snapping off another piece of Galaxy and popping it into her mouth.

‘I need to get Mark and Jake in the same room as each other so they can sort out their differences.’

‘Claire …’ Liz reaches across the table and puts her hand over mine. ‘I’m only saying this because I love you but maybe you should let them sort it out in their own time. You’re going to make yourself poorly if you don’t let go.’

‘Let go of what?’

‘Of them. You’re not responsible for everyone else’s happiness, sweetheart.’

‘None of us are happy.’

‘Least of all you.’ She gives me a searching look. ‘Mark and Jake are going to butt heads from time to time – you need to accept that.’

‘They’ll kill each other if I don’t intervene.’

‘They won’t.’

‘Jake will move out.’

She makes a soft, sighing sound. ‘Would that be the worst thing in the world? He’s nineteen years old. He makes a good living as an electrician. He could afford a one-bedroom flat.’

‘What about Kira?’

‘There’d be enough space for her too. They pretty much spend all their time in his bedroom as it is from what you’ve said. And they’d have more space.’

‘But the house would be so empty without them. And besides, I want everything to be exactly the same as it was when Billy left. That way we can just go back to normal when he returns.’

My best friend gives me a long, searching look. She wants to comment but something is holding her back.

‘What is it?’

She shakes her head. ‘Doesn’t matter.’

‘Yes, it does. What were you going to say?’

‘I just think …’ She looks away and rubs her fingers over her lips. I’ve never seen her look this uncomfortable before. ‘I just think that maybe you’re putting your life on hold for something that might not happen. I think you should … prepare yourself for bad news. It’s been six months, Claire.’

I stand up abruptly. ‘I think I should go.’

‘Oh God.’ Liz stands up too. ‘I shouldn’t have said anything. Are you okay? You’ve gone very pale.’

‘I’m fine.’

‘I’ll make us some more tea. Are you sure you won’t have some chocolate? You look—’

‘I’m going to be sick.’ I sprint from the room, one hand to my mouth, and only just make it up the stairs and into the bathroom before my stomach convulses and I dry retch over the toilet.

‘Claire?’ Liz says from behind me. ‘Are you okay?’

‘I’ll be fine. I just need some water.’

As I twist the cold tap something in the bin by the basin catches my eye.

‘No!’ Liz shouts as I reach for the newspaper. ‘Claire, don’t! Don’t read that.’

I turn my back on her and angle myself into the corner of the room as I unfold the newspaper. Billy’s name is on the front cover.

BRAWL OVER MISSING BILLY

There’s a photo beneath the blaring headline: me, wide-eyed and frantic with Mark at my shoulder. I’m reaching across the journalists for Jake who has his head against the wall, his hands balled into fists on either side of his face.

Pandemonium broke out at the six-month appeal for missing Knowle schoolboy Billy Wilkinson yesterday when his mother, Claire Wilkinson (40), was interrupted during her message to camera as Jake Wilkinson (19), the missing boy’s older brother, burst into the council offices. Wilkinson, who was visibly intoxicated, was heard to shout that he had a right to speak. His mother Claire and father Mark (42) abandoned their appeal to intervene and Mark Wilkinson was heard to exclaim, ‘Get him out of here! Get him out of here!’ Mrs Wilkinson looked visibly upset as the family was bundled out of the room.

Bristol Standard reporter Steve James spoke to a neighbour who watched the appeal on the television. ‘We’ve never had any run-ins with the Wilkinsons. They seem like a perfectly normal family but you have to wonder whether someone knows more about Billy’s disappearance than they’re letting on.’

‘Claire!’ Liz snatches the newspaper from my hands before I can read another word. ‘It’s all crap. They make stuff up to sell copies. No one believes that shit.’

She reaches an arm around my shoulders but I twist away from her, knocking her against the basin in my desperation to get out of the bathroom. It’s unbearably hot and I can’t breathe.

I take the steps down to the hallway two at a time and wrench open the front door. The second I step outside I run.

(#ulink_93a44a88-baba-59d4-9905-4932207fa365)

Chapter 8 (#ulink_93a44a88-baba-59d4-9905-4932207fa365)

I stand at the end of the bed with my feet pressed together and my arms outstretched and I tip backwards. The bedspread makes a delicious floop sound as I hit it and the bed springs squeak in protest. I can’t remember the last time I felt this happy.

‘No!’

I look to the right, in the direction of the voice, but there’s no one beside me on the bed. I’m alone in the room. There must be someone in the corridor. A woman arguing with her husband perhaps, although I can’t hear the low rumble of a male voice.

‘No!’

The voice again, quieter this time but closer, as though someone has spoken the word directly into my ear. I sit up in bed and pull my knees in to my chest.

‘NO!’

I clamp my hands to my ears but there’s no blocking out the woman’s voice as she shouts the word, machine-gun fast – NO, NO, NO, NO, NO.

It’s inside my head. The voice is coming from inside my head.

‘CLAIRE!’ it shouts. ‘I AM CLAIRE. I AM CLAIRE.’

Claire? Who is Claire? I recognize the name but I don’t want to. I don’t want to know who Claire is. I just want to get back to the seafront. Back to the sunshine and wind and the café on the edge of the pier.

‘I AM CLAIRE! I AM CLAIRE!’

The voice fills my brain, screaming and buzzing, and my head is vibrating and the light, happy feeling inside me is fading.

Dark. Light. Dark. Light.

My thoughts are dark and foggy, then brighter, clearer and then, just for a second – a split second – I know who Claire is, then the darkness returns and with it a confusion so disorientating my hands instinctively clench as I try to anchor myself to something, anything solid. There is something smooth and slippery soft under my fingers. Bed linen. I am sitting on a bed. But this is not my bed, this is not my room. There is a framed art print on the wall to my right: a faded Lowry, stick people milling around a town. There is a lone boy in the centre of the scene. He has his back to me. He’s looking at the crowd of people spilling out of one of the buildings. Who is he looking for? Who has he lost?

A shrill sound makes me jump. A small black mobile phone jiggles back and forth on the orangey pine bedside table to my right. A name flashes onto the screen. A name I don’t recognize. But the noise hurts my head and I need it to stop.

I reach for the phone and press it to my ear.

‘Mum?’ says the voice on the other end of the line.

I want to reply but I can’t talk. I can’t think. I can’t … it’s as though my mind has shattered. I can’t focus … I can’t form coherent … what’s happening to me?

‘Mum?’

‘Claire.’ I say the word out loud. It sounds strange. Like a noise, a sound, an outward breath. ‘Cl-airrrrr.’

‘Mum? Why are you saying your name?’

My name?

‘Cl-airrrrrr.’

‘Mum, you’re freaking me out. Stop doing that.‘

‘Claire.’ The word crystallizes inside my mouth. It tastes familiar. As though I’ve known it for a long time. Like buttered toast. Like toothpaste. ‘Claire. Claire Wilkinson.’

‘Oh Jesus Christ. Dad, I think she’s having a stroke or something.’

My head … my head … my brain hurts … no, aches … but not a headache … foggy … and then a thought, breaking through the darkness and I grip hold of it as though it is a rock to tether my sanity to.

‘Is my name Claire Wilkinson?’

‘Yes, yes, it is. Jesus, Mum. We’ve been trying to ring you for hours. Where are you?’

Mum. I am a mum? The man on the phone sounds scared. Is he scared for me? Or of me? I don’t know. Nothing makes any sense.

‘Where are you?’ says the voice on the phone.

‘I’m … I’m …’ There are gingham curtains at the far end of the room and a full-length mirror, smeared with fingerprints. Beneath me is a bedspread. Pink, satiny, puffy. I dig my nails into it and cling to it, rigid with fear. ‘I don’t know. I don’t recognize this room.’

‘It’s okay, Mum,’ the man on the phone says. ‘Just … sorry, hang on a second …’ There’s a muffled sound like a hand being placed over the receiver but I can still make out the low rumble of his voice.

‘Mum?’ His voice is clear again. ‘Is there a door or a window you could open? Tell me what you can see.’

I don’t want to move from the bed. I don’t want to open the pine door to my right or the closed gingham curtains at the far end of the room.

‘Please, Mum. As soon as we know where you are we can come and get you.’

We? Who is we? Who is coming to get me? I’m in danger. I need to run but I can’t move.

‘Dad’s here, Mum. Do you want to speak to him?’

‘No,’ I say and I don’t know why.

‘Are you sure?’ the man says and an image appears in my mind – vivid and sharp in the gloom – of a young man with tousled fair hair, shaved at the sides, and broad shoulders, lying on a bench, pushing weights into the air.

‘Jake?’ I venture.

‘Yes, Mum. It’s Jake. I’m at home with Dad. Liz just came round, wanting to talk to you. That’s when we realized you’d gone missing.’

I search for a memory, something, anything, to still my mind, to stop this terrifying free-fall sensation. Where is my home? Why don’t I remember?

‘Yes, I know, okay. Okay, Dad.’ The man is talking to someone else again. ‘I just asked her that. Mum, can you describe what you can see?’

I look back at the Lowry painting, at the boy standing right of centre staring into the crowd, looking for someone, then I look at the shiny pale pink bedspread, the mirror, the cheap pine table and the white tea tray.

‘I think I’m in a hotel room.’

‘Is there a phone? Can you ring reception to find out which hotel you’re in? Or is there a brochure or room-service menu anywhere?’

I slide across the pink bedspread and press my toes into the worn pile of the beige carpet, then inch my way across the room, keeping one eye on the door, and approach the table near the mirror. There’s a white china teapot on a tray and two cups and saucers. There’s also a dish containing tea, coffee, sugar and tiny cartons of milk. There are no brochures, no menus, no phone. Nothing else in the room at all other than my handbag and boots, with my socks tucked into the top, on the floor by the bed.

I touch the edge of the gingham curtain and tentatively pull it back. Outside is a low railing, a balcony and a stretch of grey-brown sea with a lump of land in the distance, an island shaped like a turtle’s back.

‘Steep Holm,’ I say and the darkness in my mind fades from black to grey at the sight of the familiar lump of rock in the distance. ‘Jake, I’m in Weston-super-Mare.’

As he relays the information I feel a sudden desperate urge to throw open the window and inhale great lungfuls of sea air but when I yank at the sash it only opens a couple of inches at the bottom.

‘Do you know which hotel, Mum?’ Jake asks. ‘If you stay where you are we’ll come and get you.’

It’s a small room: shabby but warm and clean. The floral wallpaper behind the bed is peeling in one corner and when I open the door to the en suite there are no branded toiletries, just a bar of soap in a frilled wrapper and a glass, misted with age, on the shelf above the sink. There is no welcome pack on the table that holds the tea and coffee things, no branded coaster or complimentary notepad.

‘Reception,’ I say. ‘Need to find reception.’ But then I spot a fire-evacuation notice pinned next to the door. It is signed at the bottom by Steve Jenkins, Owner, Day’s Rest B&B.

‘Day’s Rest,’ I say. ‘I’m at Day’s Rest B&B.’

‘The one we used to stay in as kids,’ Jake says and I have to steady myself against the wall as a wave of grief knocks the breath from my lungs.

Billy.

I have two sons. Jake and Billy. Billy is missing. He’s missing.

‘Mum?’ The worry in Jake’s voice bounces off me like a stone skimming the sea.

I snatch up my handbag, my boots and my socks and I reach for the door handle.

‘Mum?’ he says again as I yank open the door.

‘Billy!’ I scream into the empty corridor. ‘Billy, where are you? Where are you, son?’

(#ulink_499b651f-45d6-5e40-be29-c31af61772c1)

Friday 22nd August 2014 (#ulink_499b651f-45d6-5e40-be29-c31af61772c1)

Jackdaw44: You there?

ICE9: Yep.

Jackdaw44: Liv is a bitch.

ICE9: Who’s Liv?

Jackdaw44: Girl I was seeing.

ICE9: I didn’t know.

Jackdaw44: You wouldn’t. I keep my shit private.

ICE9: OK …

Jackdaw44: But I’m pissed off today. Need to talk to someone. I know you can keep secrets.

ICE9: It’s up to you to tell your mum what you saw, not me.

Jackdaw44: And that’s why you’re cool.

ICE9: Ha! I’ve never been called that before. So why is Liv a bitch?

Jackdaw44: She told Jess not to go out with me. She totally slagged me. Said I’ve got a small dick.

ICE9: Have you?

Jackdaw44: Go fuck yourself.

(#ulink_e2a46e30-89c3-5218-ab67-76054e770756)

Chapter 9 (#ulink_e2a46e30-89c3-5218-ab67-76054e770756)

The man behind the reception desk jumps as I slam up against it.

‘Is he here?’

‘Is who here?’ He’s a tall man, over six foot with balding hair and an auburn moustache. The buttons of his shirt strain over his gut.

‘My son. Billy. He’s fifteen.’ I raise a hand above my head. ‘He’s about this tall.’

‘Did he check in with you?’

I don’t know. The last thing I remember was running out of Liz’s house. How did I get here and why don’t I remember? Am I asleep? Unconscious? Did I trip and hit my head when I was running? But this feels real. The reception area feels solid under my fingertips. I can smell the musty aroma of old furnishings beneath the pungent scent of furniture polish. ‘I’ve got no idea. Could you check to see if he’s booked in? His name’s Billy Wilkinson.’

The man runs a thumb along the length of his gingery moustache. ‘And your name is?’

‘Claire Wilkinson.’

He reaches for a clipboard on his desk. He raises it to eye level, then mutters, ‘I can’t see a thing without my glasses,’ and replaces the clipboard and begins ferreting around in a drawer. I tap the counter as he searches. It’s all I can do not to clamber over the top and snatch up the clipboard.

‘There!’ I point at a pair of glasses on top of a paperback book. ‘Your glasses are there.’

‘Ah, thank you.’ It takes an age for him to clasp his fingers around them, for ever for him to unfold them and then, as he finally places them on his nose, he removes them again and wipes the lenses on the hem of his jumper.

‘If you could hurry. Please. It’s urgent.’

‘All in good time, Mrs Wilkinson, all in good time.’

‘Hmmm.’ He hums through his nose. ‘Room eleven, is that right?’

I hear the sound of footsteps on the stairs but it’s a middle-aged man, not Billy, who steps into the reception area and raises a cheery hand at the man behind the desk. ‘I don’t know what room I’m in. I didn’t look.’

The receptionist gives me a quizzical look, then says, ‘I’ve got a Mrs Wilkinson in room eleven. Queen room. One occupant.’

I press a hand to my forehead but the fog in my brain remains. Somehow I booked myself into a B&B in Weston. I can’t remember doing it, so either I did check in and I don’t remember or … nothing. There’s a black void where my memory should be. ‘Could Billy have checked into one of the other rooms?’

The man’s lips disappear beneath the bushy arc of his moustache. ‘I can’t give out information about other guests. Guesthouse policy.’

A vision plays out in front of my eyes, of me ripping the clipboard out of his hands and smashing him around the head with it – thwack, thwack, thwack – and I have to close them tightly shut to make it disappear. When I open them again he’s still pursing his lips, still staring at me.

‘Billy is my son. He’s missing. You have to tell me if he’s here.’

‘Missing? Goodness. Have you told the police?’

‘Yes. Six months ago. Please! I need to know if he’s here or not.’ I lean over the counter and reach for the clipboard but he snatches it away, flattening it against his chest.

‘I’ve got a flier.’ I duck down and rummage around in my bag. ‘Here!’ I hold the appeal leaflet face out so he’s eye to eye with Billy’s photo.

The man gives the briefest of nods when he’s finished reading and our eyes meet as I lower the leaflet. There. He’s giving me the look. The ‘you poor bloody woman’ look I’ve come to know so well.

‘I wouldn’t normally do this but …’ He presses his glasses slowly onto his nose, lowers the clipboard and dips his head. He trails a bitten-down fingernail along the list and my heart stills when his finger stops.

Has he …

Is it …

He shakes his head. ‘I’m sorry. There’s no Billy Wilkinson on this list.’

‘Maybe he’s using a different name?’

He places the clipboard on the desk and presses down on it with his palms. ‘It’s a small hotel, Mrs Wilkinson, just thirteen rooms. We’ve got a couple in with a teenage girl and half a dozen families with young children. I’d remember your son’s face if I’d booked him in.’

‘Does no one else take the bookings?’

There’s sadness in his eyes now. Sadness and pity. ‘No. I’m really very sorry.’

The tension that’s been holding me upright for the length of the conversation vanishes and I slump against the desk, eviscerated. It’s all I can do not to lay the side of my face on the cool wood and close my eyes.

‘I’m so sorry,’ he says again.

I look up. ‘Did you check me in?’

He nods. ‘Yes. One night, paid upfront. Don’t you remember?’

‘No. I don’t remember walking in, or even how I got to Weston. One minute I was talking to a friend in Bristol and the next …’ I can’t explain what happened because I don’t understand it myself. I came to but not in the way you do when you wake up after a nap or a long sleep. And it wasn’t like the hazy slip into consciousness after a general anaesthetic either. I was awake but my mind was muddled, tangled in a jumble of sounds, images and thoughts that gradually faded away. And then everything was sharp, in focus, as I became aware of my surroundings. And it was terrifying. Utterly terrifying.

‘Boozy lunch, was it?’ the man asks, the sympathy in his eyes dulling.

‘No,’ I say. ‘We were drinking tea.’

‘Sounds like you should get yourself to a doctor.’

‘I will. Just as soon as I get home.’ I crouch down and pull on my boots and socks. A drop of sweat rolls down my lower back as I haul the strap of my handbag over my shoulder.

‘Thank you,’ I say as I head for the door.

‘No problem.’

I wrench the door open and then, as the sea air hits me, I turn back. The receptionist looks up, Billy’s flier still in his hands.

‘Can I just ask one more thing? Was I alone when I checked in?’

‘You were, yes.’

‘And did I seem frightened? Scared? Confused?’

‘No. You seemed …’ He searches for the right word. ‘Normal.’

(#ulink_98ebc240-910a-5cca-b12d-9bbe10394482)

Chapter 10 (#ulink_98ebc240-910a-5cca-b12d-9bbe10394482)

The wind whips my hair across my face as I pull my handbag onto my knee and unzip it. There are five messages on my phone from Jake, each one more frantic than the last.

‘Mum. Stay where you are. We’re coming to get you.’

‘We’re half an hour away. I just tried to ring you. Could you pick up, please?’

‘Mum, where are you?’

‘Mum? We’re in Weston. WHERE ARE YOU?’

‘MUM, PICK UP OR WE’RE CALLING THE POLICE!’

I press the button to call him. Jake answers on the first ring.

‘Mum?’ I can hear the relief in his voice. ‘Where the hell are you?’

‘I’m on the seafront. On a bench just to the right of the pier.’

‘Okay. Don’t go anywhere. We’ll be right there.’ He stops talking and I wait for him to hang up, but then he speaks again. ‘Promise me you won’t go anywhere.’

‘I’m not going anywhere, Jake. I promise.’

‘Good. She’s on a bench, on the right of the pier …’ I listen as he relays my whereabouts to Mark and then the line goes dead.

It’s the middle of summer but the wind cuts through the thin material of my top and I wrap my arms around my body, tucking my hands under my armpits. We used to sit on this bench with the boys when they were little. They’d eat ice creams and Mark and I would drink scalding-hot tea from thin paper cups. Both boys loved our visits to Weston-super-Mare. They adored the bright flashing lights and the bleep-bleep-bleep, ching-ching-ching of the amusement arcade; Mark standing beside them, pressing two-pence pieces into their reaching palms. I’d slip outside, ears ringing, and stand on the pier, breathing in deep lungfuls of sea air, relishing the sense of freedom and space that opened within me as I looked out at the horizon.

I was eighteen when I met Mark, nineteen when we got married, twenty-one when I had Jake, twenty-five when I had Billy. I slipped effortlessly from the family I grew up in, to the one I created with Mark. I never regretted that decision, not once, but there were moments when I envied my single friends. Especially when Mark was away on a training course and whatever activity I’d dreamed up to try and entertain the boys had descended into chaos, fights and tears, and I couldn’t even escape to the toilet without small fists pounding on the door, voices begging to be let in. What would it feel like to read a book without interruption, to nurse a hangover on the sofa with a film and a mountain of chocolate, or book a holiday and just go? What would it be like to have a career where people respected you instead of taking you for granted and to have a bedroom, all of your own, where you could retreat when you’d had enough of the world? Those thoughts were always fleeting and I would dismiss them guiltily, tucking them away deep in my mind where they wouldn’t bother me. I knew how lucky I was to have a husband who loved me and two healthy children.

I press my lips together and run my sandpaper tongue against the roof of my mouth. I’m thirsty. God knows when I last had something to drink. There’s a kiosk on the edge of the pier that sells soft drinks and tanniny tea but I can’t risk moving from my bench in case Jake and Mark miss me. I unclip my handbag and rummage around inside. Gum will help with my dry mouth. I sift through papers, tissues, receipts and oddments of make-up. Long gone are the days when I’d find a small car in the base of my handbag or a half-empty packet of wet wipes scrunched up in a pocket, but my bag is still a mess. I clear it out every couple of weeks but, no matter how hard I try to be tidy, random crap still accumulates inside.

I shove a flier for a music event I’ll never attend to one side and something small and yellow catches my eye. It’s a bundle of paper tokens from the arcade, five of them in a row, folded over each other. The machines spit them out when you successfully throw a basketball into a hoop, bash a mole or shoot a target. Billy was obsessed with these tokens. You need to accumulate dozens just to buy a small lollipop but he had his eye on a shiny red remote-control car and he vowed, aged eight, not to trade in a single token until he had enough to buy that car. Mark tried to explain to him that it would take years to collect enough, and cost us more than the price of the car just to play the games, but Billy was resolute. The car would be his. He never did collect enough and a year later, worn down by his dad’s constant assertion that it was ‘all a big con’, he gave up. I bought him a similar car that Christmas but he barely looked at it, declaring that remote-controlled toys were ‘for kids’. I hated that he’d become so disillusioned so young.

For a long time after Billy gave up on his quest I’d find tokens secreted under his bed, in his pockets, in the depths of his bag and squirrelled away in his sock drawer. I kept them in one of the cupboards in the kitchen, just in case Billy had a change of heart but one day, when I was looking for something else, I realized they’d gone. When I asked Mark if he’d seen them he barely looked up from his newspaper.

‘I was looking for something and there was so much crap in that drawer I couldn’t find it. I threw them away.’

That was four or five years ago. We haven’t been to Weston as a family since. Jake and Kira have been a couple of times since they started dating but that doesn’t explain why there are tokens in my bag now. I take a closer look, examining them for a date or time stamp but they’re generic arcade tokens with the words Grand Pier printed in the centre. They’re exactly the same as the ones Billy collected all those years ago. I found some more recently, a few months before he disappeared, stuffed into the pocket of his jeans when I was doing the washing. There was a receipt too, for a room in a hotel. A few days earlier the school had rung me to say he hadn’t turned up for registration and, when I called him on his mobile, he wouldn’t say where he was, just that he was fine and he was hanging out with some mates. It was a lie. He’d obviously skived school to come to Weston with a girl. He wouldn’t say who and we grounded him for two weeks.

So where did I get these from? Could I have won them? In the six hours between leaving Liz’s house and finding myself in a bedroom in Day’s Rest B&B did I visit the arcade and play a game? Why?

I delve back into my handbag, pulling out wodges of paper, tissue packets, empty paracetamol blister packs and several red lipsticks. I remove my phone, my house keys and my make-up compact. In the bottom of the bag is a shell. It is tiny, no bigger than the pad of my thumb, pale pink with darker pigment along its scalloped edges. I went down to the beach then? Another memory comes flooding back, of me walking hand in hand with Jake and Billy along the beach when they were very little – two and six years old. The tide was out and we had our shoes off, our toes squelching into the sludgy sand. Every couple of seconds one of the boys would dip down, dig around in the sand and then jubilantly offer me a shell, stone or bottle top. Anything they spotted would immediately become the most precious of spoils, thrust upon me until my pockets were full.

Now I turn the bag upside down, attracting the attention of strutting seagulls as I litter the ground with crumbs. There is nothing else inside, no clue as to where I have spent the last six hours or what I have done. Unless … I lift my purse from my lap and peer inside: £25 in notes, a little over £3.50 in change, various bank, store and credit cards, and a tiny laminated photo of the boys one Christmas. Nothing unfamiliar, nothing unexpected, apart from a train ticket tucked between my Tesco card and my credit card. It’s dated today, with 13.11 as the time of purchase. Bristol Temple Meads to Weston-super-Mare, an open return.

‘Mum?’ Jake appears beside me, his hair flattened to his forehead, a sheen of sweat along the bridge of his nose. He’s clutching my granddad’s walking stick in his right hand. Mark is beside him. It’s only been a few hours since I last saw him but I’m shocked by how drawn his face is, how dark the circles under his eyes.

‘Claire? Oh, thank God.’ He sinks onto the bench beside me, then glances down at my lap, where the contents of my handbag are piled beneath my hands. ‘What’s all this?’

‘I was trying to understand how I got here.’ I shovel everything back into the bag, including the arcade token and the shell, then zip it shut. Worry is etched into every line on Mark’s face.

‘We thought someone had taken you,’ Jake says, leaning heavily on the stick. I gesture for him to sit down but he shakes his head. ‘We spoke to Liz and she said you suddenly got up and ran out of her house like you were on fire. Then when we rang and you didn’t know where you were …’ He breathes heavily. ‘I thought whoever took Billy had taken you too.’

Mark’s lips part and I know he wants to contradict Jake. He wants to say that we have no proof that Billy was taken by anyone. We have no idea what happened that night.

‘I did run out,’ I say before my husband can speak. ‘I remember that much but … after that …’ I shake my head. ‘The next thing I knew I was sitting on a bed in the B&B and then the phone rang.’

‘How did you get here?’ Mark asks. ‘The car was still in the drive.’

‘By train.’

‘So you remember that much?’

I shake my head again. ‘No. I found the ticket in my bag. Mark, I don’t remember getting the train, I don’t remember checking into the hotel. I don’t remember anything other than leaving Liz’s.’

‘Did you hit your head or something?’ He gently moves my hair away from my face with his hand and my heart flutters in my chest. I can’t remember the last time he touched me so tenderly. ‘I can’t see any swellings or contusions.’

I used to joke with the kids about Mark’s ‘medical speak’ after he got a job as a medical sales rep. It was almost as though he’d become a doctor himself with all his talk of angina, stents and angioplasty. Apparently it’s very unusual for someone without a medical background or degree to get a job selling pharmaceuticals to GPs and hospitals but Mark’s never been one to let someone telling him he can’t do something get in his way.

‘We didn’t realize you were missing until tea time,’ Jake says and I have to smile. I don’t imagine they would have. They’d have returned home after work and congregated in the kitchen, sniffing the air and peering into the oven and fridge. ‘Dad said you were probably round at Liz’s, pissed off with us for screwing up Billy’s appeal.’

‘Pissed off with who—’ Mark starts but Jake interrupts.

‘And then Liz came round and told us that you’d rushed out of her house and you weren’t answering your phone. She was really upset. She thought she’d said something to upset you.’

Mark shifts away from me now his ‘examination’ of my head is complete, but his eyes don’t leave my face. ‘What did she say?’ he asks.

I shake my head. If I tell him he’ll only agree. Mark’s told me over and over again that we should assume the worst about Billy. ‘Six months is a long time, Claire.’ It’s become his mantra, his invisible shield against hope whenever I tentatively suggest that maybe, just maybe, Billy could still be alive.

‘It doesn’t matter what she said.’

‘It does if it made you run off to Weston without telling anyone.’

I slip my handbag across my body, then stand up and rub my upper arms. ‘Can we just go home? Please, I just want to go home.’

Mark stands up too. ‘I think we should get you to a doctor first. Don’t you?’

(#ulink_898b9bbc-f76a-58d0-a55a-e0225b8fd24d)

Chapter 11 (#ulink_898b9bbc-f76a-58d0-a55a-e0225b8fd24d)

It’s warm in Mum’s living room. Warm and ever so slightly musty. The top of the telly is grey with dust, the magazine rack is groaning under the weight of books and magazines piled on top of it, and there are dead flowers on the windowsill; green sludge in the base of the vase instead of water. Even the spider plant on the bureau, a plant so hardy that it could survive a nuclear attack, is wilted and yellow. Its babies, trailing on the carpet on long tendrils, look as though they’ve parachuted out in an attempt to escape. Mum would declare World War III if I offered to tidy up so I do what I can whenever she leaves the room; wipe a tissue over the surfaces when she goes to the loo or tip my glass of water in the spider plant when the postman comes.

I haven’t had a chance today. She hasn’t left my side since I arrived a little after 9 a.m. I haven’t told her about my blackout yet; she thinks I’m here to talk about Billy’s publicity campaign. Mark refused to go to work until I promised him I’d spend the day with her. He’s terrified I’ll go missing again.

He’s not the only one.

The doctor doesn’t know what’s wrong with me. She ran a series of blood tests yesterday and said I’d have to wait a week for the results. It’s terrifying, not knowing what caused me to black out. What if it’s something serious like a brain tumour? What if it happens again? When I asked Dr Evans if it might she said she didn’t know.

I didn’t want to leave her office. I didn’t want to step outside the doors of the surgery and risk it happening again. Mark had to physically lift me off the chair and guide me back outside to the car.

‘See that?’ Mum slides the laptop from her knees to mine and points at the screen with a bitten-down fingernail. ‘That spike in the graph?’

I shake my head. ‘I don’t know what I’m looking at.’

‘They’re the stats for the website. We had a huge peak in page views the day the appeal went out. Over seven thousand people looked at it. Seven thousand, Claire.’

‘And that’s a good thing, is it?’ Dad says, appearing in the doorway to the living room.

‘Derek.’ Mum shoots him a warning look. ‘If you can’t say something good—’

‘It’s okay, Mum,’ I say. ‘I know what Dad’s thinking.’

‘Your dad’s not thinking anything.’ Her eyes don’t leave his face. ‘Are you, Derek?’

His gaze shifts towards me and I feel the weight of sadness in his eyes. There’s indecision too, written all over his face. He wants to tell me something but Mum’s warning him not to.

‘What is it, Dad?’

‘Derek!’

‘It’s okay. You can tell me.’

Mum pulls at my hand. ‘It’s nothing you need worry about, Claire. Just a bunch of drunks in the pub speculating. We know no one in the family had anything to do with Billy’s disappearance.’

I ignore her. I can’t tear my eyes away from my dad who looks as though he might burst from the stress of keeping his lip buttoned. ‘Dad?’

He shifts his weight so he’s leaning against the door frame and bows his head, ever so slightly, finally breaking eye contact with me. ‘They think Jake had something to do with it. I overheard a conversation when I was coming out of the loo in the King and Lion the other night. No smoke without fire and all that.’

‘Absolute rot!’ Mum snaps the laptop lid shut. ‘Everyone will have forgotten all about it by next week and then, when the dust has settled, we’ll ask the Bristol News to run a story about Billy and Jake as kids. If the Standard are going to shaft us we’ll get them onside instead. We’ll dig out some photos of the boys in their primary-school uniforms. The readers will see them when they were young and sweet and they’ll forget about Jake’s little outburst. It’s all about the cute factor. You’ll see.’

‘Cute factor?’