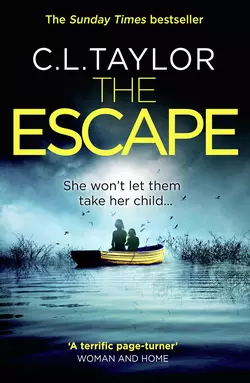

The Escape

C.L. Taylor

The Sunday Times bestseller returns with her most thrilling book yet. An unputdownable read for fans of Into the Water and The Girlfriend."Look after your daughter's things. And your daughter…"When a stranger asks Jo Blackmore for a lift she says yes, then swiftly wishes she hadn't.The stranger knows Jo's name, she knows her husband Max and she's got a glove belonging to Jo's two year old daughter Elise.What begins with a subtle threat swiftly turns into a nightmare as the police, social services and even Jo's own husband turn against her.No one believes that Elise is in danger. But Jo knows there's only one way to keep her child safe – RUN.The Sunday Times bestseller returns with her biggest and best book yet. The perfect read for fans of Paula Hawkins and Clare Mackintosh.Praise for C.L. Taylor:‘A gripping and disturbing psychological thriller’ Clare Mackintosh‘Absorbing and disturbing’ Alex Marwood‘Loved it’ Fiona Barton‘Claustrophobic, tense and thrilling’ Elizabeth Haynes

C. L. Taylor

The ESCAPE

Copyright

Published by Avon an imprint of

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street,

London, SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers 2017

Copyright © C.L. Taylor 2017

Cover photographs © Silas Manhood Photography

Cover design © HarperCollins 2017

C.L. Taylor asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008118075

Ebook Edition © March 2017 ISBN: 9780008118082

Version 2018-10-25

Praise for C.L. Taylor

‘The Missing has a delicious sense of foreboding from the first page, luring us into the heart of a family with terrible secrets and making us wait, with pounding hearts for the final, agonising twist. Loved it.’

Fiona Barton

‘Black Narcissus for the Facebook generation, a clever exploration of how petty jealousies and misunderstandings can unravel even the tightest of friendships. Claustrophobic, tense and thrilling, a thrill-ride of a novel that keeps you guessing.’

Elizabeth Haynes

‘A gripping and disturbing psychological thriller.’

Clare Mackintosh

‘As with all her books, C.L. Taylor delivers real pace, and it’s a story that keeps calling the reader back – so much so that I read it from cover to cover in one day.’

Rachel Abbott

‘A dark and gripping read that engrossed me from start to finish.’

Mel Sherratt

‘Kept me guessing till the end.’

Sun

‘Haunting and heart-stoppingly creepy, The Lie is a gripping roller coaster of suspense.’

Sunday Express

‘5/5 stars – Spine-chilling!’

Woman

‘An excellent psychological thriller.’

Heat

‘Packed with twists and turns, this brilliantly tense thriller will get your blood pumping.’

Fabulous

‘Fast-paced, tense and atmospheric, a guaranteed bestseller.’

Mark Edwards

‘A real page-turner … creepy, horrifying and twisty. You have no idea which characters you can trust, and the result is intriguing, scary and extremely gripping.’

Julie Cohen

‘A compelling, addictive and wonderfully written tale. Can’t recommend it enough.’

Louise Douglas

See what bloggers are saying about C.L. Taylor …

‘An intriguing and stirring tale, overflowing with family drama.’

Lovereading.co.uk

‘Astoundingly written, The Missing pulls you in from the very first page and doesn’t let you go until the final full stop.’

Bibliophile Book Club

‘[The Missing] inspired such a mixture of emotions in me and made me realise how truly talented you have to be to even attempt a psychological suspense of this calibre.’

My Chestnut Reading Tree

‘Tense and gripping with a dark, ominous feeling that seeps through the very clever writing … all praise to C.L. Taylor.’

Anne Cater, Random Things Through My Letterbox

‘C.L. Taylor has done it again, with another compelling masterpiece.’

Rachel’s Random Reads

‘In a crowded landscape of so-called domestic noir thrillers, most of which rely on clever twists and big reveals, [The Missing] stands out for its subtle and thoughtful analysis of the fallout from a loss in the family.’

Crime Fiction Lover

‘When I had finished, I felt like someone had ripped my heart out and wrung it out like a dish cloth.’

By the Letter Book Reviews

‘The Missing has such a big, juicy storyline and is a dream read if you like books that will keep you guessing and take on plenty of twists and turns.’

Bookaholic Confessions

‘Incredibly thrilling and utterly unpredictable! A must read!’

Aggie’s Books

‘A gripping story.’

Bibliomaniac

‘It’s the first time I have cried whilst reading. The last chapter [of The Missing] was heart-breaking and uplifting at the same time.’

The Coffee and Kindle

‘Another hit from C.L. Taylor … so cleverly written and so absorbing that I completely forgot about everything else while reading it. Unmissable.’

Alba in Book Land

Dedication

For my son, Seth Hall

‘Love you forever’

PART ONE

Charter 1

Someone is walking directly behind me, matching me pace for pace. Her perfume catches in the back of my throat: a strong, heady mix of musk and something floral. Jasmine maybe, or lily. She’s so close she’d smack into me if I stopped abruptly. Why doesn’t she just overtake? It’s a quiet street, tucked round the back of the university, with space for half a dozen cars to park but the pavement is easily wide enough for two people to walk abreast of each other.

I speed up. Elise will be the last child left at nursery, all alone and wondering where I am. I was ready to leave work at 5 p.m. on the dot, but then a student walked into the office and burst into tears. She hadn’t got her assignment in on time and she was terrified she was going to get kicked off her course. I couldn’t walk away when she was in that state. I had to talk her down. By the time she walked out of the office she was smiling again but sweat was pricking at my armpits. 5.15 p.m. I never leave work that late. Never.

My car is only a hundred metres away. In less than a minute I’ll be inside with the door shut, the engine running and the music on. I’ll be safe. Everything will be OK.

Fifty metres away.

The woman behind me is breathing heavily. She’s sped up too.

Twenty metres away.

I feel a light dragging sensation on the back of my coat; a hand, trying and failing to grab hold of the material.

Ten metres away.

High heels clip-clop behind me as I step into the road and approach the driver’s side of my car. I reach into my coat pocket for my keys but all I find is a balled tissue, a small packet of raisins and some sweet wrappers. I reach into my other pocket and my fingers close around the car keys. As I do, a hand clamps down on my shoulder.

My heart lurches in my chest as I twist round, raising my arms in self-defence.

‘Woah!’ A blonde woman my age jumps away from me, her eyes wide. She’s dressed in a thick, padded jacket, skinny jeans and heels. ‘I was only going to ask for directions.’

All the fear in my body leaves in one raggedy breath. She just wants directions.

The woman’s eyes, heavily ringed with black kohl, don’t leave my face. ‘Do you know where I can get a bus to Brecknock Road?’

I feel a jolt of surprise. ‘Brecknock? That’s where I live.’

‘Is it?’ she says. ‘What a coincidence.’

I thought she was in her forties like me but her line-free forehead and arched eyebrows are betrayed by a sagginess to her jaw and a crinkling to her neck that suggest she’s at least ten years older.

She glances at my hand, resting on the window of the car. ‘I don’t suppose you’re going there now?’

‘I’m sorry?’

‘Brecknock Road. Could I have a lift?’

I don’t know how to react. I don’t want her in my car. Not when I’m feeling like this. I need to calm myself down before I get to the nursery. I don’t want Elise to see me in a state.

The blonde’s eyes flick towards the pavement as a young bloke in a heavy overcoat strolls past. He’s on his phone and doesn’t give either of us a second glance.

‘My son and daughter are exactly the same. Always got their noses in their phones,’ she says convivially as the man disappears around the corner and we are alone again. Either she’s completely unaware of how awkward and uncomfortable I feel as a result of her request or she just doesn’t care.

‘I … um …’ I put my keys in the lock. ‘I’m sorry. I’m not going straight home. I need to collect my daughter from nursery and—’

‘Elise, isn’t it?’

My breath catches in my throat. ‘I’m sorry?’

‘Lovely name. Quite old-fashioned but that’s all the rage these days, isn’t it? My daughter-in-law wanted to call my granddaughter Ethel. Ethel, for God’s sake.’

‘How do you …’ I study her face again but there’s no spark of recognition in the back of my brain. I don’t remember ever seeing this woman before. ‘I’m sorry, have we met?’

She cackles, a low sound that gurgles in the base of her throat, and holds out a hand. ‘I’m sorry. I should have introduced myself. I’m John’s mum, Paula. He lives just down the street from you. I’ve seen you and your little girl getting into your car in the mornings when I take my granddaughter to the park. I look after her sometimes. I’m from Taunton. I don’t get into Bristol often.’ She glances meaningfully at my car.

‘So am I OK for a lift? Now you know I’m not a serial killer?’

I am frozen with indecision. I don’t know anyone called John but it’s a long street. To say no to a lift would be rude, and I don’t want to make an enemy of any of our neighbours, not when it’s such a lovely street, but this isn’t something I do. This isn’t part of my routine.

‘Please,’ she says, ‘I’m babysitting tonight and John will be wondering where I’ve got to.’

I make a split-second decision. It will be quicker to give her a lift than say no and risk wasting more time with a discussion about it. ‘OK. But I’ll have to drop you at the nursery. It’s not far from Brecknock.’

‘Cheers, love. Really appreciate it.’

She waits for me to unlock the driver’s side door then rounds the car and gets in beside me. I put on my seat belt and put the keys in the ignition. Paula, in the passenger seat, doesn’t reach for her seat belt. Instead she runs a hand over the dashboard then squeezes the latch on the glove compartment so it drops open. She rummages around inside, pulling out CDs, receipts and manuals, then reaches down and runs a hand underneath her seat.

I stare at her in disbelief as she twists round in her seat and looks into the footwells in the back seat. ‘Can I help you with something?’

She ignores me and clambers into the back seat and feels behind and beneath Elise’s car seat, then lifts the parcel shelf and peers into the boot.

‘Paula.’ I unclip my seat belt. ‘Could you stop doing that, please?’

She snaps back round to face me, her lips tight and her eyes narrowed. ‘Don’t tell me what to do, Jo.’

The transformation is shocking, all trace of her cheerful, friendly demeanour gone. She lied to me. She doesn’t have a son called John who lives on our street. She’s never strolled down to Perrett’s Park with her granddaughter. And I never told her my name.

‘I want you to get out of my car,’ I say as steadily as I can.

The smallest of smiles creeps onto her lips as she straightens her jacket and settles herself into the back seat. She reaches out her left arm and drapes it over Elise’s car seat.

‘Pretty girl, your daughter,’ she says under her breath but loud enough so I can hear it. ‘Isn’t she, Jo?’

The malevolence in her eyes makes me catch my breath.

‘Get out,’ I say again. A man has appeared at the end of the street. If I open the door and shout he’ll hear me. Paula sees me looking.

‘Now, now. No need to be rude. I’ve lost something. That’s all. And I think your husband might know where it is.’

I stiffen. ‘Max? What’s this got to do with Max?’

Paula glances over her shoulder again – the man has reached the car behind mine – and pulls on the door catch. ‘He’ll know what it’s about. Just tell him to get in touch. Oh, and, there’s something else.’

She digs into her pocket with her free hand.

‘You should keep an eye on your daughter’s things,’ she says as she places a small, soft, multicoloured glove on Elise’s car seat.

‘And your daughter,’ she adds as she gets out.

Charter 2

Max Blackmore sighs as his mobile phone judders to life, vibrating on the smooth wooden desk that separates him from his editor. He snatches it up and looks at the screen. Jo, again. It’s the third time his wife has called him since he left for work at 8 a.m. and he’s already had to reassure her that yes, he does think it’s OK for Elise to go to nursery with a bit of a cough and yes, he will stop by at the chemist to get more Calpol before he gets home. He’s been ignoring his home mobile for the last half an hour and now she’s ringing his work mobile instead.

His editor Fiona Spelling leans back in her chair and crosses her arms. She’s doing ‘the face’, the one that signifies that her genial mood is on the cusp of switching to irritable. ‘Do you need to get that?’

He tucks the phone into the inside pocket of his jacket. ‘It can keep.’

‘Are you sure? Because you know she’ll ring me if she can’t get through to you.’

Max grimaces. He should never have given Jo Fiona’s direct line. It was meant to calm her – so she could check he was OK if he couldn’t answer his mobile – but she rings the number so often she now has it on speed dial. Literally speed dial, programmed into her chunky, ancient Nokia. One for him, two for her mother, three for nursery, four for her boss and five for Fiona. He’s begged her to delete Fiona’s number but she won’t have it.

‘It’s her agoraphobia,’ he says. ‘It makes her overly anxious.’

‘But she works at the university as a student support officer, doesn’t she? How bad can it be if she can hold down a job?’

Max smiles ruefully. He thought the same as Fiona once: that you’re basically housebound if you suffer from agoraphobia, but it’s not as ‘simple’ as that – something Jo has explained to him countless times. She isn’t afraid of going outside, she’s afraid of situations where she can’t escape or get help.

‘It’s bad,’ he says. ‘Really bad. Jo works part-time but she won’t take Elise to the park or the zoo. She won’t even go food shopping any more, not since she had a panic attack in the corner shop because she thought someone was looking at her strangely.’

‘Wow.’ His boss arches an eyebrow.

Fiona doesn’t know the half of it. He and Jo haven’t had sex for over a year. They had a dry spell before, when she was so afraid of getting pregnant she wouldn’t let him anywhere near her, but then they’d conceived Elise and he’d assumed that everything would go back to normal. It didn’t. It got worse.

‘Anyway, Max,’ Fiona says, gesturing towards her screen. ‘Congratulations. I’ve read your story and it’s good. Very good. How does it feel?’

‘How does what feel?’

‘To get a conviction off the back of your investigation? Five years, he got, didn’t he?’

Max smiles for the first time since he sat down. He would have loved to see the look on Ian White’s face when the police turned up to arrest him. Evil bastard. He’d set up a national chain of money-lending shops that charged single mums, pensioners and people on benefits ridiculous amounts of interest and then turned up at their home and threatened them with violence when they couldn’t pay it back. Coercion, drug-taking and violence were rife. Max had witnessed one of Ian’s goons shoving an old man up against the wall of his own home when he said he wouldn’t be able to eat for a week if he paid up. He couldn’t react. He couldn’t stop him. All he could do was pray that the tiny camera in his glasses was getting enough footage to convict the bastards.

‘And you weren’t worried about your cover slipping? No one at Cash Creditors suspected you?’ Fiona asks.

‘There were a couple of sticky moments but I talked my way out of them.’

‘That doesn’t surprise me in the least.’ His boss smiles tightly. ‘So, are we going to have to start calling you Donal MacIntyre now then?’

‘Nah.’ He waves a dismissive hand. ‘He’s old hat. Max Blackmore will do fine, although if you want to call me “sir” that would be fine too.’

He stiffens as Fiona’s smile slips and she raises an eyebrow. Shit. He always takes a joke one step too far.

Charter 3

The second the buzzer sounds and the door is un-locked I fly through the nursery, dodging coat stands, a papier-mâché homage to The Hungry Caterpillar, and several members of staff.

‘Elise?’ A bead of sweat trickles down my lower back as I fumble with the catch of the gate at the ‘twos room’. Half a dozen pairs of tiny eyes look up at me in interest and alarm as I step into the room. None of them belong to my daughter.

‘Everything OK, Jo?’ Sharon, a woman with a tight ponytail and an even tighter smile, looks up from her position in front of the children, a picture book in her hands. Another of the nursery staff, a sweet eighteen-year-old called Bethan, looks up from the table she’s cleaning. She smiles a hello but there’s confusion in her eyes.

‘Jo?’ Sharon says and I search the faces of the children again, just in case I missed one.

‘I can’t see Elise. Where is she?’

I don’t wait for her reply. Instead I open the door to the garden. It’s empty; the sandpit abandoned; an array of brightly coloured plastic tools lying on the sand, illuminated by the security light.

‘Jo?’ Sharon appears beside me, an irritated expression on her face. ‘What’s the matter. I’m sure Elise is in—’

‘Mummy!’

The plaintive cry from across the room makes me turn. And there she is, my tiny little girl with her dark blonde hair still in the bunches I tied this morning, clutching the hand of Alice, her key worker. I like Alice. She’s kind and gentle and she doesn’t give me lectures about timekeeping if I’m five minutes late.

‘I did a wee wee,’ my daughter says proudly as I dash across the room.

‘In the toilet,’ she adds as I lift her into my arms and press my face into the soft warmth of her neck.

‘It was her idea,’ Alice says. ‘She said she didn’t want to wear nappies any more.’

‘My God.’ I hold my daughter tightly and stroke her hair over and over. ‘Oh my God.’

‘Jo?’ The tone in Alice’s voice changes. ‘Is everything OK? You look very pale. Is it your stepdad? Did something happen?’

I want to tell her that I have just driven across Bristol at breakneck speed, certain that the woman who tricked her way into my car had somehow harmed my daughter. I rang Max over and over again but he didn’t pick up. Neither did Fiona, his boss. I tried to call the police but I couldn’t breathe, never mind talk, and I ended the call before it connected. My hands were shaking so much it took me three attempts to get the keys in the ignition and the car started. I want to tell Alice all these things but, more than anything else, I want to get Elise home. We will both be safe there.

‘Jo!’ Alice shouts as I hurry through the nursery with Elise’s legs wrapped around my waist and her small face buried into my neck. ‘You haven’t signed her out. And you’ve forgotten her coat!’

I fumble with the door latch. Other parents are waiting to be let in, watching me through the glass panel. Their smiles turn to frustration. I can’t get my fingers to work properly, I’m shaking so much. Finally, Sharon appears beside me. She thrusts Elise’s bag and coat at me and then opens the door with one swift turn of the latch. I mutter an apology to the other parents as they part to allow me out of the door.

‘She looked a bit wired,’ a woman says, sotto voce, but loud enough for me to hear, as I step out onto the street.

‘Probably a couple too many glasses of wine at lunch,’ someone comments and a chorus of laughter follows me out onto the street.

Back home I pause as I reach the living room, Elise’s cup of milk in my hand. Outside in the street a woman is laughing – a loud, throaty cackle that makes all the hairs go up on my arms. Paula knows the name of our road. She’s seen me take Elise to the park. She’s probably watched us leave the house. I’ve already checked – twice – that all the doors and windows are locked but I dart to the front door anyway and jiggle on the handle to make sure. Still locked.

I hurry back into the living room where my daughter is still on the sofa, staring at the TV, a blanket over her legs, and Effie Elephant, her favourite soft toy, clutched to her chest.

‘Milk,’ she says as I cross the room, peel back the curtain and peer outside. Two women, both of them dark-haired, saunter down the street. The one on the right cackles again and her friend punches her playfully on the arm. It’s not Paula. But that doesn’t mean we’re safe.

‘Here you go, sweetheart.’ I force a smile as I hand the cup of milk to my daughter. Her gaze doesn’t flicker from the screen. She’s entranced by Makka Pakka placing rocks, one by one, into a wheelbarrow. She’s relaxed and happy … I just wish I felt the same.

‘Mummy’s just going to pack a few things so we can go and visit Granny and Grandad for a few days. I’ll be back in a second. I’m just going upstairs.’

I move quickly, running from room to room, gathering up clothes, nappies, toys, toiletries and medication, freezing whenever I hear a strange sound, shouting down to my daughter to check she’s OK. I throw everything into a large wheeled suitcase and then return to Elise’s bedroom. I stand in the middle of the room with my hands on my hips as I scan the shelves for anything I may have missed. I can’t believe Max did this to us. He swore to me that he would never put our family in danger. He reassured me over and over again that we would be safe, that no one would come after us as a result of his investigation. And I believed him. I don’t know who was more naïve, me or him. Our marriage has been on its last legs for a while. I’ve tried to keep it going, for Elise’s sake, but I can’t do this any more. I can’t spend my life with a man who puts his career before his family’s safety.

I return to my bedroom and zip up the suitcase then open it again. Have I got absolutely everything I need for Elise? It doesn’t matter if I’ve forgotten something of mine but we’ve got a problem if I forget something of hers. I can’t ask Mum to leave Andy’s side to go to the shops for me. And if I go …

I grip hold of the chest of drawers and take a steadying breath. I can do this. I’ve driven up to Mum’s loads of times and nothing has happened. I know the route: M5, A41, all the way up. Approximately three hours. It’s nearly 7 p.m. now and Elise will probably sleep the whole way.

‘Sweetheart!’ I bump the suitcase down the stairs, abandon it in the hall and step back into the living room. ‘Mummy needs to put a nappy on you before we go. Just in case you fall asleep and have an accident.’

Elise looks at me and shakes her head.

I hold out a nappy and give her an encouraging smile. ‘Let’s just pop this on now and then we can go. We’re going to see Granny and Grandad.’

‘No.’ Her bottom lip wobbles. ‘No nappy, Mummy.’

‘Elise, please.’ As I sit down on the sofa I hear the sound of keys being turned in the front door.

A second later my husband flies into the room, his cheeks ashen and his eyes wide. He takes one look at Elise and scoops her up into his arms, pressing a hand against her back as he holds her tightly against his chest. He notices me watching.

‘Why didn’t you answer your phone?’ he says through gritted teeth. ‘I thought Elise was … I … you can’t leave a message like that and then NOT ANSWER YOUR PHONE.’

Elise yelps in shock as his shout fills the living room.

‘Sorry, sorry, baby.’ He strokes her hair, his wide palm cupping the back of her head. ‘I didn’t mean to scare you.’

‘Max,’ I say, keeping my voice as steady as I can. ‘Can we talk about this in the kitchen, away from Elise?’

‘I’m sorry!’ Max says, the second we step into the kitchen. ‘I shouldn’t have shouted at you. I was just … fucking hell, Jo, you really scared me.’ He rubs his hands over his face, peering at me through the gaps in his fingers.

‘You were scared? Where the hell have you been? I rang you. I called you as soon as it happened.’

‘I was in a meeting with Fiona.’

‘Seriously?’ I can’t keep incredulity out of my voice. ‘Have you got any idea what I’ve—’

‘I’m sorry. OK. Just tell me what happened.’

He listens, his hands clenching and unclenching at his sides, as I tell him about being followed down the street, about Paula getting into my car, about the threat she made to Elise. I pause when I reach the end, waiting for a reaction, but Max doesn’t say anything.

‘What?’ I say. ‘Why are you looking at me like that?’

‘I …’ He runs a hand over his hair. ‘I’m shocked I guess. I’m … trying to make sense of what happened.’

‘Make sense of what? A stranger got into my car, started rooting around for something and then threatened Elise. And she knows you, Max. What is there to make sense of? We need to ring the police.’

‘The woman said her name was Paula?’

‘Yes.’

‘Paula what?’

‘She didn’t tell me her surname.’

‘What did she look like? I worked with someone called Paula about six or seven years ago. She left on maternity leave and didn’t come back.’

‘Was she blonde, early fifties?’

‘No. She was in her twenties, mixed race. And she didn’t have a problem with me.’

‘You can’t think of anyone else called Paula who might know you? Someone you investigated or did a story on?’

‘No. I’d remember if I had. And I’ve only done one investigation, you know that.’

‘But you’ve interviewed loads of people and run hundreds of stories. There has to be at least one Paula that you’ve pissed off over the years. Maybe we should ring Fiona,’ I add before he can object. ‘She could search the archives or something. Then we’ll have something to take to the police.’

‘No.’ Max shakes his head. ‘Jo, I’m not ringing Fiona. For one she’ll be at home by now, and two …’ He tails off.

‘Two, what? Why are you looking at me like that again?’

‘Like what?’

‘Like you don’t believe me.’

‘I’m not.’

‘Yes, you are. You’re giving me the same look you gave me when I told you about my panic attack in the corner shop.’

‘Oh God.’ Max slumps back against the kitchen unit. The cheap MDF creaks under his weight. Our house isn’t the only thing that’s falling apart. ‘Do we have to talk about that again?’

‘Yes, we do. I told you I felt threatened by the way that woman was looking at me and you said—’

‘That she was just concerned because Elise was having a tantrum. Jo, it’s her shop. If I owned a shop and some kid was screaming their head off I’d stare at the mother too!’

‘Today was different! Paula threatened me. She threatened Elise. I can’t believe you’re not taking this seriously. Look!’ I reach into the pocket of my jeans and pull out my daughter’s rainbow-coloured glove. ‘She gave this to me. There’s no way she could have got hold of it unless she’d been near Elise. I put both gloves in her pocket when I took her to nursery this morning.’

My husband runs a hand over the back of his neck and gives me an exasperated look. ‘Have you checked Elise’s pockets for the other glove?’

I glance towards the front door where I dumped my daughter’s things as soon as we came in.

‘That’s a no then.’ Max strides out of the kitchen and into the hallway. He picks up Elise’s coat, thrusts his hands into the small pockets and then turns his attention to the bag. He pulls out our daughter’s spare clothes one by one. When it’s empty he turns his attention to the other clothes, hanging up on hooks by the front door. Scarves, hats, coats, jackets, hoodies and umbrellas fall to the floor as he selects, searches and then discards them.

‘She must have taken both gloves,’ I say from behind him. ‘Max, we need to ring the police.’

But he’s off again, sidling past me to the pile of coats hanging on the banister.

‘Did you wear this today?’ He holds up a soft grey coat from Wallis.

‘Yes. Why?’

He thrusts a hand into one pocket, then the other, then holds his palm out towards me. Lying alongside a screwed-up tissue and a packet of raisins is a tiny rainbow-coloured glove.

‘Look.’ He plucks the other glove from my fingers and places it on his palm, making a pair. ‘Two gloves. They were both in your pocket. Did you blow your nose while you were walking to the car?’

I automatically touch my nose. My nostrils are red raw from the streaming cold I’ve had for days. ‘Possibly. I can’t remember.’

‘Well, there you go then. One of the gloves fell out of your pocket when you took out a tissue. And this Paula woman picked it up and gave it back to you.

‘You’re tired, Jo,’ he adds before I can respond. ‘You haven’t been sleeping well and work has been stressing you out. A stranger got into your car and you freaked out. That’s perfectly understandable.’

Irritation bubbles inside me at the patronising tone of his voice and the ‘poor little woman’ look on his face, and I have to fight to keep my tone level.

‘You’re right, Max. I am tired. And I am stressed. And OK, maybe I got it wrong about the glove, but I didn’t misinterpret what Paula said. She definitely threatened me.’

‘OK.’ He touches a hand to my arm. It’s a weary gesture, one that matches the look in his eyes. ‘Let’s say, for argument’s sake, that we do ring the police.’

‘OK.’

‘Now, imagine that you’re a police officer. Someone rings you up to tell you that a stranger handed you something that you dropped and then told you to look after your daughter’s things. Does that sound like a crime to you?’

‘It does if they also say, “And your daughter” with real menace.’

‘Like the woman in the shop looked at you with menace?’

‘That was different. I’ve already told you that!’

‘OK, fine.’ Max crosses the kitchen, lifts the phone from its cradle and hands it to me. ‘Here. Ring the police. I’ll be in the living room if you need me.’

I watch as he shuffles away down the hallway, hands in his pockets, his shoulders curled forward. As he disappears into the living room Elise squeals with joy and I turn the phone over and over in my hands.

Charter 4

Weakness. That’s what I saw in her eyes. Weakness, fear and indecision. If a stranger had coerced me into letting them into my car I’d have yanked them straight back out again. No, scratch that, I wouldn’t have let them in in the first place. But Jo’s soft. She’s vulnerable. She walks with her head down, eyes fixed on the pavement, fingers twitching against the tired, worn material of her winter coat. She’s a natural target. How can you have respect for someone like that? Someone who flinches if you look at her the wrong way? Who doesn’t trust her instincts? Someone who is so very, very easy to manipulate …

Charter 5

I didn’t ring the police. I thought about it all evening, debating the pros and cons as Max turned on Netflix and settled back on the sofa with a bag of Doritos and a bottle of beer. I could barely look at him. Every crunch, every munch, every slurp made my skin prickle with anger. When we were first married he’d jump to my defence if someone was even inadvertently rude to me on a night out. He’d walk nearest the road on a rainy night to protect me from splashes. He’d jump out of bed and grab his baseball bat if I heard a noise downstairs. I thought he’d be on to the police the second I told him what had happened. Instead he looked at me like I’m some kind of hysterical neurotic. How can I ring the police if my own husband doesn’t believe me? All I’ve got is a first name and a description. What could they possibly do with that? Then there’s the fact that I’d have to go into the police station and that’s not something I can deal with right now.

At 11 p.m., when Max finally went to bed, I thought about ringing my best friend Helen who lives in Cardiff with her little boy Ben. But it was too late. She’d have been in bed for an hour at least. Instead I sent her a text asking her when would be a good time to have a chat, then I took out my laptop and Googled jobs and places to live in Chester. I’ve been thinking about moving away from Bristol for a while. What happened last night was the last straw.

Now, my shoulders loosen and my grip on the steering wheel relaxes as I pull into the lane that runs behind Mum and Dad’s house on the outskirts of Chester. Elise is asleep in the back of the car, her dark blonde head lolling against her chest, her fingers unfurled and relaxed, Effie Elephant resting on her lap.

Mum appears at the garden gate as I pull on the handbrake and turn off the engine. Her dark, dyed hair looks longer than I remember. It curls over her ears and hangs over her eyebrows. She brushes it out of her face as she approaches the car and taps on the window. I’m shocked by how tired she looks.

‘Jo?’ she says as I unwind the window. ‘What are you doing here? I said to Andy that I could hear a car pulling up.’

Mum’s been living in the UK for over thirty years, we both have, but while my Irish accent disappeared within a year of me starting school, hers is as strong as it was the day we left.

‘Didn’t you get my text?’

‘Phone’s off. You know I don’t like to waste the battery.’

I can’t help but smile. ‘It might have been urgent, Mum.’

‘Wasn’t though, was it? You’d have rung the house phone if it was.’ She glances into the back of the car as Elise stirs in her sleep. ‘Babby all right?’

I want to tell her what happened yesterday. She’d understand why I was so scared for Elise’s safety, why I still am. But she’s got enough on her plate looking after Dad. I can’t put this on her too. Just being here and seeing her face makes me feel like I can breathe again.

‘She’s fine.’ I gesture for Mum to move away from the door so I can open it. ‘We just fancied seeing you and Dad. How is he?’

Mum gives me a long look. ‘He’s not great, love.’

It’s the beginning of February but it’s so hot in Mum’s house that I have to strip both me and Elise down to our T-shirts within minutes of walking through the front door.

‘I keep it warm for Dad,’ Mum says as I hang our discarded clothes over the back of a chair. ‘He really feels the cold now.’

‘Can we see him?’

‘Let me go and see how he is.’

She disappears through the living-room door and into the hallway. A year ago I’d hear the sound of the stairs creaking as she made her way up to the master bedroom but Dad’s been sleeping in the dining room for a while now. He was diagnosed with motor neurone disease three years ago. He’d been unusually clumsy for a few weeks – dropping the coffee jar in the kitchen, spilling tea on himself and tripping over the rug in the living room – and Mum complained to me on the phone that she couldn’t get him to see a doctor. When he started having trouble with his speech he finally agreed to see someone. The diagnosis was made scarily quickly and within six months he was walking with a stick. Two years later he was in a wheelchair. Now he’s unable to leave his bed.

‘What’s this?’ Elise asks and I dart towards her, intercepting her grabby little hand before she can snatch one of Mum’s porcelain figurines from the windowsill.

‘It’s a ballerina,’ I say, guiding her fingers away. ‘Isn’t she pretty?’

She nods enthusiastically, her gaze still fixed on the statuette. ‘Yes.’

I walk my daughter around Mum and Dad’s compact living room, pointing out all the other ornaments: the life-sized china robin, the small crystal vase, the little boy reading a book under a windmill, the fairy plates hanging on the wall and a brown and white cow. Every single thing in this room was bought in the UK. Other than Mum’s accent, this house is devoid of any trace of our Irish heritage. I gave up trying to talk to her about Ireland years ago. She shuts down whenever anyone questions her about where she’s from or why she left. I only know that her best friend was called Mary because Mum got uncharacteristically drunk at my wedding and confided in my friend Helen. She told her that she’d wanted Mary to be her bridesmaid at her own wedding, nearly forty years earlier, but it hadn’t been possible. That she missed Mary and hadn’t seen her for over thirty years. When Helen suggested that it’s never too late to reconnect yourself with someone you love, Mum had replied, ‘It is if they hate you.’ When Helen probed for more information, Mum disappeared off in search of another glass of champagne.

Mum may have briefly opened up about her old best friend but there’s one person she’s never talked about – my real dad. He vanished three weeks before my eighth birthday.

She told me that he’d gone away for work but I didn’t believe her. I’d seen her friends cross the street when she waved hello. I’d noticed the way voices would drop and our neighbours would stare when I popped into the shop to grab a pint of milk. Kids in the playground started telling me that my dad was a bad man and their parents had told them not to talk to me any more. I didn’t understand. I was sad that my dad wasn’t at home any more and I knew my mum was upset too. But no one would tell me when he was coming back.

I was excited when I got back from school on the afternoon of my birthday and found Mum waiting at the front door with two packed suitcases. I thought we were going to visit Dad, wherever he was. I thought it was a birthday surprise. I was still excited when, ten minutes later, Uncle Carey turned up in his battered car and drove us to the train station. I didn’t want to spoil the surprise but I couldn’t stop myself from asking Mum where we were going. She unpursed her thin lips and said, ‘Away. That’s all you need to know.’ Twelve hours later we were in England. And I never saw my dad again.

It was just me and Mum for two years. And then she met Andy. It can’t have been easy for him, taking on someone else’s child – especially one on the cusp of puberty – but he took it all in his stride. He gave me space when I needed it, he played board games with me when I was fed up and let me walk his cocker spaniel Jessie when we all went out. He told me knock knock jokes that were so rubbish they made me laugh and he tried, and failed, to introduce me to sci-fi. He was kind, funny and awkward and I couldn’t help but warm to him. When he asked me if I would mind if he asked my mum to marry him I burst into tears. If he married Mum that would make us a family and he’d be my dad. There wasn’t anything I wanted more.

‘Dad’s asleep,’ Mum says now as she steps back into the living room and lowers herself into an armchair. ‘I’ll need your help turning him in a bit if that’s OK. The carer’s due this afternoon but I don’t want to leave him that long. He’ll get bedsores.’

‘Of course.’

‘CBeebies,’ Elise says, pointing at the blank television in the corner of the room.

Mum moves to get up but I tell her that I’ll do it. I settle Elise on the other side of the sofa with Effie and, as the Mr Tumble theme tune fills the room, I take the seat nearest to Mum.

‘How is he?’ I ask, keeping my voice low so Elise can’t hear. ‘How’s Dad?’

Mum twists the gold band on the third finger of her left hand. ‘He’s not good, Joanne. The consultant has him on Riluzole but it’s making him very tired. And he’s got a mask now, to help with his breathing. There’s been talk of a feeding tube but he won’t have it.’

Dad hasn’t been able to talk for at least a year but he lets you know if he disagrees with something. I saw the look in his eyes and the way his face twisted when Dr Valentine gently suggested that he might want to consider hospice care. Mum was vociferous in her response to the idea, her soft voice unusually loud as though she was literally speaking for both of them. No hospitals and no hospices. Dad wants to die at home. The disease has robbed him of so much – of his freedom, his voice, his body, his dignity – but deciding how and where he dies is his last vestige of control.

‘Oh, Mum.’ I reach for her hand but she’s too far away and my fingers graze the soft wool of her cardigan instead. ‘I wish we were closer. I wish there was more I could do. I hate it, being so far away. I feel so guilty.’

‘No.’ She sits up a little straighter in her seat. ‘Don’t you be saying things like that. You have your own life, Joanne. A house, a job, a husband and a babby. She needs to be your priority, not us.’

‘But what if we moved closer? I hate the idea of you coping all alone. I know you’ve got the carer but—’

‘I’ve Elaine Fairchild next door. And my friends from the church. I’m being looked after. Don’t you worry.’

But no family. No brothers or sisters or nieces or nephews. I know Mum still keeps in touch with her sisters Sinead and Celeste and her brother Carey – I’ve seen the Christmas cards on the mantelpiece – but she’s too proud to ask for help. She’s independent and strong-willed. She had to be, upping and leaving her friends and family and starting a new life with me as a single mum in England, a country she’d never even visited before.

‘I’m serious, Mum. I’ve been looking at jobs. There’s one here at the university. I could do it standing on my head. There are loads of good nurseries nearby and I’ve seen a lovely little bungalow in Malpas. We’d be just down the road.’

She gives me a sideways look. ‘And what does Max think of this plan?’

I glance at Elise, sucking her thumb and staring intently at Grandad Tumble. ‘I haven’t talked to him about it yet.’

‘Jo …’ Mum narrows her eyes. ‘What is it that you’re not telling me?’

I want to explain how much I’ve been struggling and how the move could help me as well as her and Dad. I thought that life would get better after Elise was born. I thought that, as soon as I held her warm, wriggling body in my arms, all the hurt and pain of losing Henry in the second trimester of my pregnancy would lessen. I thought my breath would stop catching in my throat, that the panic in my chest every time I left the house would subside. That the terrible, all-encompassing dread that something awful was just about to happen would disappear. But it didn’t. It got worse. We had lost Henry and I was terrified that we’d lose Elise too. I couldn’t sleep because I was convinced that she’d stop breathing the moment I closed my eyes. I wouldn’t let her out of my sight for fear that someone would snatch her. For months I refused to let Max take her out of the house in her pram because I was certain that, if he did, I’d never see either of them again. I had several panic attacks – once after Max went back to work and I tried to go to a local mother-and-baby group in the church hall, another time in the pharmacy when I went to buy Calpol for Elise – but I kept trying, I kept working out in front of the TV, I kept doing my mindfulness exercises. I refused to let it beat me. And then two months ago Mum told me that the consultant had given Dad less than three months to live and the walls began closing in on me again.

When I started thinking about jobs and houses in Cheshire I never truly believed that it could happen. How could I ever move to a different part of the country when I couldn’t even go to Tesco alone? It was wishful thinking. A pipe dream. But when Paula got into my car yesterday and threatened my daughter, something changed. I didn’t turn to jelly. I didn’t faint or cry or curl up in a ball. I told her to get out and I went in search of my little girl. Elise’s safety and well-being are more important to me than anything else. I know it’s not right, the way she’s living now, cooped up in the house with me, and I want to change that. I want her life to be an adventure and not a prison.

‘I’m not happy, Mum,’ I say. ‘Max and me … it’s not been good for a while and it’s been getting worse. I want a divorce.’

‘A divorce. Are you quite, quite sure? Perhaps couples counselling might help? Or your local priest?’

My heart sinks as she continues to offer suggestions. Elise is totally, blissfully oblivious to what’s going on. Her whole world is going to fall apart over the next few weeks and months and it’s up to me to protect her as best I can. I can only hope that Max will agree to an amicable separation but, deep down, I know that’s not going to happen. Despite his threats to leave in the past, he would never abandon me and Elise. He’s an only child and both of his parents are dead – we’re all he’s got. When I tell him that I want to move to Chester with Elise he’s going to be devastated.

Charter 6

Chester? CHESTER? Max stalks from room to room, his hands balled into fists and tucked under his armpits. Jo’s been planning a move to Chester and she didn’t think to mention it to him? He’d logged on to her laptop while his was updating and discovered that she’d left three tabs open in Firefox – one for a student-support job at the University of Chester, one for Rightmove and one for a primary school in Malpas. Was that the real reason she’d gone up to Chester? To go to an interview or attend a viewing before she visited her parents? He nearly called her yesterday, when he found the laptop, then changed his mind. This is a conversation they need to have face-to-face. He’s been quietly seething for nearly 48 hours.

He glances at his watch as he moves from the master bedroom to Elise’s room. 5.17 p.m. Jo texted him earlier to say they’d be home around fiveish.

He squats down to pick up some building blocks and a fluffy bear that have been abandoned in the middle of the room and transfers them to a pink plastic toy bucket beside his daughter’s cot. He pulls the curtains closed and straightens Elise’s duvet. Then, with nothing else to occupy himself, he sits on the floor beside her cot. He runs a hand over the multi-coloured Peppa Pig duvet cover then reaches for a book from the shelves set into the alcove: Snug as a Bug, his daughter’s favourite book. He’s read it hundreds of times, Jo has too. It’s part of Elise’s bedtime routine: teeth, pyjamas, milk, book. He’s surprised Jo didn’t take it with her.

Anxiety twists at his stomach as he gazes around his daughter’s bedroom, at the white clouds floating on grey wallpaper on the opposite wall, at the framed picture of a penguin gripping a bouquet of balloons, at the tent-shaped den Elise fills with teddies and rarely enters. It’s so quiet without his daughter bouncing around the room, singing gobbledegook songs in her breathy high-pitched voice. So empty. This is what it would be like if Jo took her away. He closes his eyes to block out the thought, but it’s not fear he’s feeling any more. It’s anger. Here he is, tearing himself apart at the thought of losing his daughter when his own father didn’t give two shits about him and his brother. You wouldn’t have caught Jeff Blackmore moping about in the bedroom, cooing and sighing over a duvet cover and a favourite book. He didn’t even know who his kids were half the time.

Max holds it together when his family returns just after 6 p.m. He welcomes Jo back into the house with a kiss on the cheek and then scoops Elise up and into his arms and hugs her tightly before setting her back on her feet. She speeds off into the living room, demanding that he play bricks with her. It takes him a couple of seconds to realise that Jo hasn’t followed them. She’s still standing in the hallway, one hand pressed to her lower back, the other to the wall. She tells him that she put her back out when she helped her mother turn Andy and she’s been in the most terrible pain ever since. The three-hour car journey was unbearable, she says, and now she can barely move. He helps her into the living room and takes some of the weight as she lowers herself to the floor so she can lie on her back, then he retrieves the suitcases from the car and carries them up to the bedroom.

Two hours flash by as he feeds Elise, doles out ibuprofen and a glass of water to Jo, and then does the bedtime routine single-handedly as his wife lies on the living-room rug barking out orders. ‘Don’t forget to brush her teeth.’ ‘Make sure you plug the Gro-Clock back in’. ‘Have you got her milk?’ His irritation increases each time he hears her voice.

When he finally returns to the living room, with Elise safely tucked up in her cot, Jo has managed to drag herself into a sitting position, her back pressed up against the base of the sofa. For five minutes they have been sitting in silence, staring at the ‘Night, night. See you tomorrow morning at 6 a.m.’ image on the television screen. Jo’s semi-crippled condition has unnerved him. He knows that now is not the time to have a conversation about what he discovered on the laptop but he can’t push it out of his mind. There’s no way he can go to work tomorrow with the matter left unresolved. It will eat away at him all day.

‘So.’ He coughs lightly. ‘When were you planning on telling me that you want to move to Chester?’

Jo tenses but she doesn’t turn to look at him. ‘Sorry?’

‘I saw the sites you’d been looking at on your laptop. The house, the job, the school.’

‘Can we talk about it tomorrow, please?’ Her voice is as stiff as her body.

‘No, I want to talk about it now.’

Jo continues to stare at the green glow of the television. ‘Please, Max. I’m in pain.’

Max takes a steadying breath in through his nose. If there was nothing to it she’d tell him as much, but her silence is scaring him. What’s she playing at? Why won’t she just talk to him? ‘And you think I’m not?’

‘Don’t do this, please.’ She turns her head slowly to look at him. ‘I’ve had an awful day. Dad’s got so much worse and I really don’t want to fight with you tonight.’

How can he argue with that? He can’t and he shouldn’t. But there’s always something with Jo. Something that means he has to bite his tongue rather than talk to her about the things that are worrying him. First it was the panic attacks, then the agoraphobia. Now her dad’s dying. Andy’s been touch-and-go for the last couple of years. They’ve lived their lives on a knife edge since before Elise was born, exchanging worried glances each time Brigid rings in case it’s bad news. And now, on top of everything, Jo has put her back out. Another reason to block him out.

‘Is this to do with what happened before you left?’ he asks. ‘Are you pissed off with me because I didn’t call the police?’

Anger flashes on her face. ‘Elise was in danger but, instead of supporting me, you patronised me. Poor old Jo, reacting to every tiny little thing. This is our daughter we’re talking about. I don’t care if we’re being overcautious, so long as she’s safe.’

‘Elise was in no more danger than if she’d been crossing the road or playing in the park. Not that she ever gets to do that, when she’s so wrapped up in cotton wool that she’s suffocating in her own home.’

‘DON’T!’ Jo snaps. ‘Don’t you dare go there, Max.’

‘I think we should talk about it. I think we should discuss the fact that you’re too ill to take our daughter anywhere other than to and from nursery but you’re well enough to plan a move up to Chester, are you? To start a new job? To take her to a new nursery? To build a new life for yourself?’

‘I’m trying to get well, Max.’ Jo’s gaze is still steely but her voice sounds choked, as though she’s trying not to cry. ‘I’m trying to do what’s best for everyone: for Elise, for Mum, for Dad, for me.’

‘But not for me?’ It takes every last bit of control to hide the pain that’s tearing at his chest. He’s always known that he’s last on Jo’s list of priorities, but hearing her say it hurts like hell.

‘Yes, for you!’ Jo says. ‘I’ve done nothing but support you for the last twelve years but you never listen when I try and tell you what I want.’

‘I listen!’ Max jumps up from his seat. ‘I do nothing but listen.’

‘No, you don’t. You don’t listen to a word I say. I told you not to get into investigative journalism because you were putting us at risk, and you patted me on the head and told me not to worry my silly little self.’

‘That’s not true.’

‘It is. You put yourself first, Max. You’ve always put yourself first. It’s always been about you and your career. I put up with that when it was just you and me but we’re a family now.’

‘You think I don’t know that?’

‘Well, you obviously don’t care. If you did you would have given a shit when I told you that a stranger had threatened our daughter and—’

‘I LOVE ELISE!’ Max roars with pain and anger and frustration. His right hand unclenches and he swipes at the framed photos on the mantelpiece, sending them clattering to the ground. Why is she being like this? Why is she attacking him when he’s just trying to do the right thing? He’s only ever tried to do the right thing. He’s vaguely aware of Jo screaming at him to stop as he tornadoes through the room, grabbing, smashing and destroying all the things he paid for, everything he worked so hard for, and then he hears it, he registers the threat that makes his blood go cold.

Charter 7

I’m watching you, Jo. I’ve been watching you for a long time. I know where you go, what you do and who you talk to. And I know what your weak spot is. Some women become more powerful when they become mothers. They become more alert to danger, more ready to react, to defend. But you’re no tiger mother, Jo. You’re prey. And if you try and disappear down a rabbit hole with Elise I’ll come after you. I want what’s mine and I know exactly how to take it back.

Charter 8

I should never have threatened Max, but I just wanted him to stop. I’d never seen him that out of control before. I begged him to calm down but it was like he couldn’t hear me, or our daughter whimpering upstairs, and so I told him that, if I moved away, he’d be lucky if he ever saw Elise again.

He froze. He stopped still in the middle of the room and he stared. Not at me. Not at the broken picture frames lying on the rug. At nothing. Then he said, ‘Elise is crying. I’ll go and check she’s OK,’ and he stalked out of the room before I could object, leaving me in a sea of smashed glass and splintered wood.

As Max’s footsteps clump-clump-clumped on the landing above me and the low rumble of his voice drifted down the stairs, I rolled onto my hands and knees, gritting my teeth as I forced myself up and onto my feet. He was halfway down the stairs by the time I got to the living-room door. In his right hand was his black sports bag.

‘Max,’ I said. ‘I’m sorry. Can’t we just talk about—’

He walked straight past me, opened the front door and then looked back. His eyes were so filled with pain and hurt it took my breath away.

‘Mummy,’ Elise says now as I hobble across the kitchen to the cupboard near the sink where we keep our medicine. ‘Mummy, back owie?’

‘Yes, sweetheart. Mummy’s back’s still hurting.’ I root around the boxes of plasters, Calpol and indigestion tablets but the strongest painkillers we have are a couple of paracetamol.

I swallow them with a glass of water then take Elise’s plate from the table and drop it into the sink, then swipe at the jam on the front of her top with a damp dishcloth. I would change her but it’s taken me so long to do the simplest thing this morning and we’re already running fifteen minutes late.

Somehow I manage to wrestle my daughter into her shoes and coat and out the front door. As I do, the door to number 35 opens and our next-door neighbour Naija appears, walking backwards as she attempts to wrestle her huge double buggy out of the house and onto the path.

‘They’re doing my head in,’ she says, gesturing towards her eighteen-month-old twin boys who are red-faced and screaming. ‘I can’t wait until we go on holiday next week.’

‘I can imagine. I remember when—’ I break off mid-sentence.

Someone’s watching us. I can sense it, even without turning my head.

And there she is, Paula, standing on the corner of my street staring straight at us.

‘Naija, can you keep an eye on Elise for a second?’ I reach down and attempt to lift my daughter over the low wall that separates our front gardens but, as I do, my back spasms violently and I wince. I see a flash of amusement on Paula’s face and then she’s off, walking down the street towards Wells Road.

‘It’s OK.’ Naija reaches for Elise and lifts her over the wall. As soon as she’s in her arms I take off, hobbling down the path.

‘Paula!’ I try to run but I can’t stand up straight. Instead I half rock, half gallop along the pavement, gritting my teeth against the pain. It seems to take for ever to reach the corner and, as I turn it, my heart sinks. She’ll be long gone. An eighty-year-old could outrun me today.

‘Paul—’

I stop sharply. Paula is standing right in front of me, her hands in the pockets of her black padded jacket, her high-heeled feet planted wide. I would have ploughed straight into her if I hadn’t stopped so quickly, but she doesn’t jolt or step backwards as I draw up next to her. Her kohl-lined eyes flick from the top of my head to the scuffed Clarks shoes on my feet, and then rest on my arm, twisted behind me, my hand on my lower back.

‘Hello, Jo.’ The top half of her face doesn’t move as her lips curl up into a smile.

‘What are you doing here?’

Her fixed smile doesn’t slip. ‘My son lives here. I told you.’

‘No, he doesn’t.’

‘Doesn’t he?’ She tilts her head to one side. Her mascara-loaded eyelashes unblinking. Her cold, blue eyes fixed on mine. ‘That’s strange. I could have sworn I just came from his house.’

‘What number does he live at?’

She glances up Wells Road towards the small crowd assembled at the bus stop a couple of metres away. A woman with her child glances quickly away, embarrassed at being caught eavesdropping on our conversation, but an elderly woman continues to stare. Paula makes eye contact with her, tilts her head towards me and rolls her eyes. She may as well make twirling circles with her index finger whilst pointing at her temple.

Further down Brecknock Road, Naija is still standing outside her house, one hand on the buggy, the other clutching Elise. When she sees me looking, she lifts a hand from the buggy and holds it out, palm upturned. What’s going on? Paula shifts position. She’s watching them too.

‘Leave us alone,’ I hiss. ‘I don’t know who you are or what you want but if you don’t stay away from us I’ll call the police.’

Paula leans in so close I can smell cigarettes on her breath. ‘And tell them what, Jo?’

I react instinctively, pressing my palms against her horrible shiny jacket and shoving her away from me. ‘Leave us alone!’

‘Oooh.’ She looks back towards the bus stop. Now everyone is staring at us, their jaws agape. ‘That was assault!’ She looks back at me. ‘I think the bloke in the black coat is going to call the police. He’s got his mobile out, look.’

I don’t look. I’m so angry I’m shaking.

‘Just leave,’ I say through gritted teeth. ‘Just leave me alone.’

‘I will when your husband returns what he took.’

‘He didn’t take anything from you. He doesn’t even know who you are!’

‘Doesn’t he?’ A slow smile creeps onto her face. ‘He would tell you that, wouldn’t he?’

‘What’s that supposed to mean?’

‘Just tell him to return my property, Jo,’ she says as she turns to leave.

‘Why me?’ I shout after her as her high heels clip-clop on the pavement. ‘Why not talk to Max?’

She turns back and there it is, the same tight-lipped, narrow-eyed look she gave me in my car. ‘Because you’re more fun, Jo.‘

Charter 9

I fight back tears as I shepherd Elise through the heavy glass door and into nursery. I don’t really know what I’m doing here.

I didn’t tell Naija what had happened with Paula. Elise was staring up at me with big, worried eyes and I knew that, if I said a word, I’d burst into tears. Besides, I barely know my next-door neighbour. We’ve made small talk about the children in the front garden and I once emailed her some information about a course she was interested in but we’ve never been in each other’s homes.

‘Come on then, sweetheart. Let’s get your coat off.’

I feel breathless and sweaty as I pull at the elasticated cuff around my daughter’s wrist. If I can just follow the schedule – nursery, work, nursery, home – everything will be OK. Elise will be safe here. I overreacted before. There’s no way anyone could take a child out of the nursery without a member of staff knowing. When Elise started I had to provide Sharon with a list of anyone I might send to pick her up, along with a description of them, and then I had to provide a password. They won’t release Elise to anyone who doesn’t know it.

With Elise free of her coat I lead her towards the twos room, hoping desperately that Sharon isn’t in today. She gave me such a strange look the last time I came in, and there’s something about her that makes me feel ill at ease. A week doesn’t go past when she doesn’t take me to one side to tell me off for not labelling Elise’s clothes or for forgetting to bring in family photos for a display.

‘Jo!’ A perplexed-looking woman with a baby in her arms and a shoeless toddler at her feet gestures for me to come to her aid. I’m so stressed I can’t remember her name. ‘You couldn’t hold Mia while I put George’s trainers on, could you?’

She thrusts the baby into my arms before I can object. My lower back twinges as I take the weight of the child.

‘Dat’s George,’ Elise says, pointing as the small boy gleefully throws his trainers across the hallway and his mother chases after them.

‘Baby,’ she adds, pointing at the red-cheeked, drooling bundle in my arms.

‘I’m so tired,’ the other woman says, crouching down beside her son. She grabs one of his socked feet and wiggles a shoe onto it. ‘Mia’s still waking me up every three hours for a feed. She’s six months old, for goodness’ sake. I swear George was sleeping through by now.’

‘Looks like she’s teething,’ I say as I dab away some of the drool on the child’s chin with the muslin tucked under her neck.

‘Four teeth! She’s started biting when I feed her. I don’t think my nipples can take much more.’ She glances up at me. ‘Sorry, too much information.’

‘It’s fine. I know exactly where you’re coming from. The first time Elise did that I was so shocked I shoved her away and she ended up on the floor!’

The other mum laughs but the sound comes to an abrupt halt and she hurriedly looks away. Sharon has appeared beside me with her arms crossed and a disapproving look on her face.

‘I don’t think potentially injuring a child is a laughing matter, do you?’

Sharon doesn’t wait for me to respond. Instead she reaches for my daughter’s hand and leads her towards the gate. ‘Come on, Elise, let’s get you inside.’

I watch open-mouthed as she ushers my daughter inside without giving me a chance to say goodbye to her.

‘Don’t worry about Sharon,’ the other woman says in a low voice as she helps her son to his feet and reaches for her baby. ‘She’ll understand when she has kids.’

‘OK, Jo,’ says the policewoman on the other end of the line. ‘I’ve created a log of everything you’ve told me and you’ve got your incident number, haven’t you?’

I tap the number written on the pad of paper in front of me, even though she can’t see it. ‘Yes, I’ve written it down.’

‘An officer will visit you at home tomorrow to take some more details.’

‘Do you … do you have any idea what time?’ I feel awful trying to pin her down, given how accommodating she was when I said I’d struggle to make it to the police station because of my agoraphobia.

‘It could be any time, I’m afraid.’

That means I’ll have to take a half-day’s holiday from work and then pray they don’t turn up when I leave to collect Elise from nursery. Or maybe I could keep her home with me?

‘OK,’ I say, ‘that’s fine.’

‘Great. If anything else happens between now and then, make a note of the date, time and what happened and give us a ring back, quoting your incident number. And if you feel in any immediate danger call 999. OK?’

‘OK.’ I look up to the ceiling as tears well in my eyes, then take a steadying breath. I didn’t expect the police to take me seriously, not after the way Max reacted.

‘Is there anything else I can help you with?’

I want to tell her that I’m scared. That I’ve been home for less than five minutes and every noise, every shadow that’s passed the living-room window, has made me jump. I want to tell her that I’m scared that when another police officer comes round to talk to me I’ll have to admit that I shoved Paula in the street. There were witnesses – at least half a dozen. If the police track Paula down and she presses charges my career will be over. I’d lose my job at the university and I won’t find another. Not here. Not in Chester. Nowhere.

‘Wait!’ I say before she can put the phone down. ‘I’ve changed my mind. I don’t want anyone to come round and see me.’

‘Why’s that then?’ I can hear the frustration in her voice.

‘I … I … it’s fine. It’ll be fine. I … I think I overreacted. Sorry, the line’s breaking up. I appreciate your time. Thank you. Bye!’

I jab at the end call button, wincing as I sit back against the sofa cushion. I lasted less than half an hour at work. Within ten minutes of sitting down in my chair I was in so much pain from my back I wanted to cry. Then, when I rang my GP to try and arrange an appointment and the receptionist said there was no space for five days, I did cry. Diane, my boss, took one look at me and sent me home. I nearly passed out when I got into the car, and the pain is going nowhere.

I check my phone to see if there’s been a reply from Max to the voicemails and texts I sent him at work, apologising for what I said last night and telling him what happened with Paula this morning. When I woke up I picked up my phone, expecting to find a grovelling apology from my husband. He’s lost his temper before but he’s never smashed things up. Never. That was so out of character it scared me. But there were no new messages and I haven’t heard from Max all day – not a call, not a text, nothing. I don’t know what I expected. Maybe an ‘I’m sorry’ or an ‘I should have believed you’ or even a ‘let’s talk’. But no, nothing at all. He knows he was out of order last night. The only possible reason for his silence is because he’s paying me back for what I said. That’s why I apologised. One of us had to break the deadlock.

I hobble into the kitchen, leaning on the walls for support, and rifle through the medicine cupboard again but nothing stronger than paracetamol has miraculously appeared overnight. I’ve already taken the two ibuprofen that Diane gave me but they haven’t touched the edges. I pick up my handbag from where I left it on the kitchen counter when I came in, and upend it. My purse, keys, make-up, tissues, various pieces of paper, an assortment of change and my phone tumble out. And something else – a packet of pills that don’t belong to me. I pick them up and turn them over in my hands. They’re some of Dad’s muscle relaxants. Mum thrust them at me when I mentioned that my back was hurting but I shooed her away, telling her that a couple of paracetamol would sort me out. She must have slipped them into my bag before I left. There’s no advice slip in the packet but a quick Google reveals side effects including dizziness, drowsiness, a dry mouth and possible addiction. Nothing overly scary. I make a split-second decision and pop two out of the blister pack and into my mouth. As I swallow them down with a glass of water a wave of exhaustion crashes over me. I barely slept a wink last night: a combination of the pain and the aftermath of the argument with Max. I glance at my watch as I shuffle back down the hallway, check the front door is double-locked, then step into the living room and ease myself down onto the sofa. It is 12.15 p.m. I’ll just grab a couple of hours’ sleep and, with any luck, I’ll feel better when I wake up. I might even be able to do a couple of hours’ work on my laptop before I go and pick up Elise.

I wake with a start but my mind is so foggy it takes me a couple of seconds to realise where I am. The living room is dark, the sofa is lumpy and uncomfortable and the house is silent. I turn my head. It’s dark outside but the blinds are still open. Unease pricks at my consciousness but sleep still has a grip on me, making me groggy and slow. I twist my wrist up towards my face and squint at the display through the gloom – 6.14 p.m.

Six-fourteen! I shoot up into a sitting position then wince and press a hand to my lower back. Six fourteen! I should have been at the nursery for five-thirty to pick up Elise. Oh my God! A cold chill courses through me as I snatch up my mobile. Five missed calls: three of them from the nursery, two of them from Max.

I ease myself onto my feet and grab my coat from the banister. I hit the voicemail button on my phone and press it to my ear as I stumble out the front door and half hobble, half run down the street.

‘Hello, Jo. It’s Sharon from nursery. You were due to pick up Elise fifteen minutes ago. I’m sorry to have to remind you about timekeeping again but you really should let us know if you’re going to be this late.’

‘Hello, Jo. It’s Sharon again. Could you give us a ring as soon as you get this?’

‘Hello, Jo. It’s nearly six o’clock and Elise is really quite distressed that no one has come to collect her. We’ve rung your husband.’

‘Jo, it’s Max. Where are you? I just got your message about Paula, and the nursery just rang me to say that you haven’t picked up Elise. Where are you? Ring me! Please! As soon as you get this!’

‘I’m going to get Elise. Ring me the second you get this.’

My hand shakes as I run a hand over my face, pushing the hair off my damp forehead. The nursery is only a couple of blocks away but it feels miles away. Six hours! I passed out for six hours. My phone rang five times and I didn’t hear a thing. Shit. I should never have taken Dad’s pills. I should have gone to the chemist. I should have—

I stop short outside the nursery. There are no cars parked up outside and no lights on inside. The entrance hall is empty of buggies. The coat rack, normally heaving with tiny jackets and bags, is bare. I wrap a hand around one of the metal bars on the gate but I don’t bother opening it. I’m too late. Elise is gone.

Charter 10

When his phone rings at 6.35 p.m. Max snatches it up and presses the call answer button. For over half an hour he’s been pacing the room as call after call all ended in the same way – ‘No, I haven’t seen Jo all day,’ ‘No, I haven’t heard from her’ and ‘I hope she’s OK. Let me know.’

He gives Elise a reassuring smile as he presses the phone to his ear but she’s too busy to notice. She’s playing on the double bed with a plastic doll he found in her nursery bag.

‘Jo?’ He keeps his voice low, so as not to worry his daughter. ‘Jo, are you there?’

‘Where’s Elise? Is she with you?’ He can hear the fear in his wife’s voice.

‘Yes. Where the hell are you?’

His wife sighs with relief then promptly bursts into tears. ‘Oh my God,’ she cries between sobs. ‘Oh my God. Oh my God. Oh my God.’

Max stands up and carries the phone into the bathroom. He can still see Elise through the open door but she’s nearly out of earshot now. ‘Jo, can you tell me where you are?’

‘I’m … at home.’

‘Are you OK?’

‘Yes.’ He hears her take a deep breath. It’s punctuated by short sharp sobs but she’s calming down.

‘What happened?’

There is silence apart from a sniff followed by a soft hoo-hoo sound as his wife breathes in through her nose and out through her mouth.

‘Jo, what happened?’ Max asks again.

‘I woke up and it was dark. I overslept. I came back from work earlier because my back was hurting and I fell asleep on the sofa. Oh God. I feel so—’

‘You were asleep?’ He’d seen her calls flash up on his screen earlier in the day but he’d ignored them. He was in court, covering a domestic battery case, and it wasn’t until he was back in the office and the nursery rang that he realised something was wrong. He’d tried to ring Jo and, when she didn’t answer her phone, he started to worry. Had something happened at work or was she marooned somewhere, caught in the grip of a panic attack? Then he remembered what she’d told him about Paula.

‘You were asleep?’ he says again, unable to keep the incredulity out of his voice. ‘Jo, we went back to the house but it was locked from the inside. I banged on the door and shouted through the letter box. Didn’t you hear me?’

‘No.’ Her voice quavers. ‘I didn’t hear a thing.’

‘I’ve been ringing all your friends. I was going to call the police.’

‘Oh God. I’m sorry. Where are you? Can you bring Elise home? I need to see her.’

‘I …’ Max pauses. He can’t dismiss the niggling thought at the back of his brain. ‘I made a lot of noise, Jo. I banged and banged. No one could have slept through that.’

‘That’s because I … I took something.’

His grip on the phone tightens. ‘What?’

‘Some muscle relaxants my mum gave me. They were Dad’s. I was in so much pain, Max, and the doctor wouldn’t see me.’

‘You took prescription drugs meant for a man who’s dying from motor neurone disease? Are you mad?’

‘I was desperate! I was in pain. You have no idea—’

‘No, Jo. You have no idea. Did Sharon tell you that Elise wet herself when no one came to pick her up?’

‘No. I—’

‘Or that she had to put her in another child’s knickers because you forgot to take her bag in this morning? And she was filthy, Jo. Her top was dirty, her hair hadn’t been brushed—’

‘Please, Max. Don’t make me feel worse than I already do. I could barely move this morning but I still got Elise ready the best I could. I didn’t mean to forget her. I didn’t do it on purpose!’

Jo continues to try and explain herself but Max has stopped listening. He’s thinking about his dad. He was twelve the first time he found him passed out on the sofa. He’d just got in from school and there was a strange, bittersweet, almost vinegary scent in the air when he opened the front door. He found the tinfoil, sticky with brown liquid, on the bathroom floor.

‘Have you done it before?’ he asks.

‘What?’

‘Taken drugs. At home?’

‘Are you serious?’

‘I wouldn’t have asked if I wasn’t.’

Over the last couple of months Jo’s behaviour has become increasingly erratic. He’d put it down to her agoraphobia and mental health. No, she’d put it down to that. Neither of them could pinpoint why she was getting worse instead of better. Unless she was self-medicating …

His wife sighs. ‘I can’t believe you’re even asking me that.’

‘Sharon said you seemed out of it when you picked up Elise the other day.’

‘That was after Paula threatened me! Jesus, Max. Would you listen to yourself? You’re being ridiculous. Just bring Elise home.’

‘She also said you deliberately dropped Elise when she was a baby.’

‘I was breastfeeding and she bit me! I didn’t do it on purpose. Jesus, Max. Why are we even having this conversation? Just bring Elise home or I–I’ll—’

‘Do what? Take her to Chester? Make sure I never see her again?’ Max is shaking with anger. Jo didn’t see the state their daughter was in when he turned up to collect her. The nursery staff had done the best they could to keep her occupied but her eyes were red and puffy, her cheeks tear-stained. As if she hadn’t been through enough – being kept indoors all the time when other little kids were laughing and playing in the sunshine. He’d done his best to understand what Jo was going through. He’d supported her, he’d listened to her, he’d put his own needs last, telling himself that all Jo needed was a bit of time. But she was turning into someone he didn’t recognise.

‘Max, don’t. I said I was sorry about that. I sent you a text and—’

‘Have you got any idea how worried I’ve been, Jo? I thought that Paula had hurt you. Have you rung the police yet?’

Jo pauses for a beat. ‘No.’

There’s something about the hesitation in her voice as she says the word ‘no’ that makes Max frown.

‘Why the hell not? Last night you had a go at me because I wasn’t taking you seriously and now …’ he sighs. ‘We’re going round in circles here. Look, we’re in the Holiday Inn and Elise is fine. She can sleep here with me tonight and I’ll take her to nursery in the morning. If you pick her up after work we can talk more then. OK?’

‘I … I don’t know. I really want to see her, Max.’

‘She’s fine. Honestly.’ He watches as his daughter clambers off the bed and toddles towards him, arms reaching for a hug, a huge smile on her face. ‘I’m sorry for going off the deep end but I was worried, OK, for you and Elise.’

‘I’m sorry too. I didn’t mean to scare you. Honestly, Max. When I woke up and realised what had happened I …’ She pauses. ‘Can I talk to Elise? Please. I need to hear her voice.’

‘Sure.’ He places the phone against his daughter’s ear. ‘Elise, sweetie. It’s Mummy. Say hello.’

He listens as his daughter has a garbled conversation with her mother then he wrangles the phone away from her again.

‘I need to go. There’s a Tesco down the road and I need to grab some overnight things for Elise and some clean clothes for nursery tomorrow.’