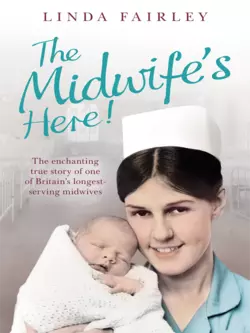

The Midwife’s Here!: The Enchanting True Story of One of Britain’s Longest Serving Midwives

Linda Fairley

The Sunday Times bestseller‘Delivering my first baby is a memory that will stay with me forever. Just feeling the warmth of a newborn head in your hands, that new life, there’s honestly nothing like it… I’ve since brought more than 2,200 babies into the world, and I still tingle with excitement every time.’It’s the summer of 1968 and St Mary’s Maternity Hospital in Manchester is a place from a bygone age. It is filled with starched white hats and full skirts, steaming laundries and milk kitchens, strict curfews and bellowed commands. It is a time of homebirths, swaddling and dangerous anaesthetics. It was this world that Linda Fairley entered as a trainee midwife aged just 19 years old.From the moment Linda delivered her first baby – racing across rain-splattered Manchester street on her trusty moped in the dead of night – Linda knew she’d found her vocation. ‘The midwife’s here!’ they always exclaimed, joined in their joyful chorus by relieved husbands, mothers, grandmothers and whoever else had found themselves in close proximity to a woman about to give birth.Under the strict supervision of community midwife Mrs Tattershall, Linda’s gruellingly long days were spent on overcrowded wards pinning Terry nappies, making up bottles and sterilizing bedpans – and above all helping women in need. Her life was a succession of emergencies, successes and tragedies: a never-ending chain of actions which made all the difference between life and death.There was Mrs Petty who gave birth in heartbreaking poverty; Mrs Drew who confided to Linda that the triplets she was carrying were not in fact her husband’s; and Muriel Turner, whose dangerously premature baby boy survived – against all the odds. Forty years later Linda’s passion for midwifery burns as bright as ever as she is now celebrated as one of Britain’s longest-serving midwives, still holding the lives of mothers and children in her own two hands.Rich in period detail and told with a good dose of Manchester humour, The Midwife’s Here! is the extraordinary, heartwarming tale of a truly inspiring woman.

Linda Fairley

The Midwife’s Here!

The Enchanting True Story of One of Britain’s Longest Serving Midwives

Copyright

This book is a work of non-fiction based on the author’s experiences.

In order to protect privacy, names, identifying characteristics, dialogue and details have been changed or reconstructed.

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

and HarperElement are trademarks of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

Published by HarperElement 2012

Linda Fairley asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

THE MIDWIFE’S HERE. © Linda Fairley 2012. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780007446308

Ebook Edition © APRIL 2012 ISBN: 9780007446315

Version 2016-10-17

Dedication

For Peter, who told me I could write this book.

He was so proud of me, and I know he’d have loved it.

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

Preface

Chapter One

‘It feels like we’re in the Army!’

Chapter Two

‘I really am becoming an MRI nurse!’

Chapter Three

‘I didn’t expect to be looking after people who are actually ill’

Chapter Four

‘People are dying … This is harder than I thought’

Chapter Five

‘I have come to tender my resignation, Matron’

Chapter Six

‘Nurse Lawton, you have been granted permission to witness a birth if you come quickly’

Chapter Seven

‘Unless you ladder your stockings, to my mind you haven’t made a good job of dealing with a cardiac arrest!’

Chapter Eight

‘T’ Eagle ’as landed’

Chapter Nine

‘To qualify as a midwife you’ll need to deliver forty babies in ten months’

Chapter Ten

‘Feeling the warmth of a baby’s head in your hands, that new life, I’d honestly never experienced anything like it’

Chapter Eleven

‘Knickers and tights off, ladies!’

Chapter Twelve

‘Get these birds out of here, NOW! Where’s the hygiene? Tell me that!’

Chapter Thirteen

‘So you’ve had the baby? … Let’s have a cup of tea and a cigarette then’

Chapter Fourteen

‘She’s at top o’ stairs!’

Chapter Fifteen

‘He’s not touching her privates!’

Chapter Sixteen

‘Your baby is showing signs of life … He’s alive!’

Picture Section

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Read an excerpt from Linda Fairley's new book (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright

About the Publisher

‘Go, and do thou likewise.’

Prologue

‘The midwife’s here!’ Mick Drew exclaimed, nudging his wife Geraldine as I approached her bedside.

Mick gave me a broad smile that was filled with a mixture of gratitude and relief. It was a look I was growing accustomed to seeing on the faces of husbands with expectant wives, and I had learned that the more imminent the birth, the more appreciative and thankful the smile became.

It was early 1971 and Geraldine was about two months away from giving birth, but she was in the highly unusual position of expecting naturally conceived triplets, which no doubt more than trebled her loving husband’s concern.

‘Flamin ’eck, how long? I’ll go round the twist!’ Geraldine had balked when I outlined her birth plan a few months earlier, explaining that her multiple pregnancy automatically meant she would be admitted to the antenatal ward in Ashton General Hospital for bed rest when she was seven months pregnant.

‘That’s the rule, I’m afraid,’ I explained, thinking it was unfortunate Geraldine wouldn’t benefit from our brand new maternity unit, which wasn’t due to open until the end of the year. ‘Don’t you worry, we’ll take good care of you in here and I’m sure you’ll enjoy the break.’

Geraldine tittered. ‘Well, I suppose rules is rules, though I’m not sure how my old man will take it!’

She and Mick already had three young children, and quite how he was going to cope alone with them while his wife was in hospital was not yet apparent.

‘I suppose it’ll be good training for him,’ Geraldine said cheerfully the last time I saw her at antenatal clinic. ‘Seeing as how we’re going to end up with six! He’ll have to get used to doing his share and keeping an eye on three of ’em.’

I was pleased to see Geraldine had an easy-going nature and was quick to see the funny side of life. She would doubtless need those qualities to cope with a brood that size.

‘As for me, I’ll just have to get meself a pile of good mags to keep me busy, won’t I?’ she winked. ‘I’m sure I’ll cope.’

It hadn’t taken Geraldine long to settle herself into the antenatal ward, aided amiably by Mick, who was a round, ruddy-cheeked man who visited often and had such a spring in his step he appeared to bounce down the corridor, flared brown trousers swishing round his ankles.

Every day he wheeled in a little tartan shopping trolley of provisions for his wife and greeted her by planting a huge kiss on both cheeks, and then on the lips. ‘One for each baby,’ he always beamed before handing Geraldine a packet of sweets or a paper bag containing drinks and magazines.

‘How’s she doing, Nurse?’ he always asked me earnestly. ‘Everything as it should be?’

‘Yes, everything seems fine,’ I reassured him. ‘Your wife is doing very well indeed.’

‘Terrific!’ he grinned. ‘She’s a coper, my Geraldine, that she is.’

‘In’t he a smasher, Nurse?’ Geraldine would often say after his visits. ‘I’ve got meself a real diamond in Mick, that’s for sure.’

I got so used to seeing Geraldine plumped up on a pillow, swathed in a garish purple satin nightgown Mick had bought her at Stockport market, that after just a few weeks it felt as if she’d always been with us. Sometimes she even talked the nurses into letting her help out with the tea trolley, dishing out cuppas to other patients.

‘Does me good to stretch me legs,’ she’d grin as she waddled round the ward shouting out, ‘Two sugars as usual, Mrs Crowe? Best keep your strength up!’

‘Evening, Nurse!’ she’d always bellow when I turned up for a shift. ‘How are you tonight?’

‘It’s me who should be asking you that,’ I’d laugh, marvelling at how much energy Geraldine had in her condition. ‘I’ll be round later, make sure you’re OK.’

When a woman is expecting triplets she is at greater risk of developing high blood pressure, protein in the urine and oedema of the ankles, all of which are complications that can threaten the safety of the mother and baby.

I knew Geraldine wasn’t averse to sneaking to the toilets for a cigarette because I often smelled it on her breath, so I was always very particular about checking her blood pressure, in case smoking affected it.

Mick smuggled in the cigarettes, usually hidden in the paper bag he brought beneath a bottle of Vimto, a copy of Woman’s Weekly and a quarter of pineapple cubes from the corner shop. He tried to be fairly discreet about the cigarettes, but Geraldine didn’t really care if she got caught smoking, and often left empty packets and dog ends on the locker beside her bed.

One night as I sat beside Geraldine for a routine blood pressure check, I asked her how she was feeling being stuck in hospital for so long.

‘Right as rain,’ she chirped. ‘To tell you the truth, you were right. I’m enjoying the rest.’

Lowering her voice and staring down at her wedding ring, she added bashfully: ‘I’m glad I don’t have to face ’im indoors all the time, too.’

‘Whatever do you mean?’ I asked. ‘Mick thinks the world of you, and I thought you said he was a diamond?’

Geraldine leaned her head towards me conspiratorially and fixed her big green eyes on mine. They were glinting with what looked like a mixture of fear and excitement.

‘Can you keep a secret, Nurse?’ she whispered.

Before I had a chance to answer, Geraldine was mouthing the words: ‘They’re not his!’ As she did so she pointed dramatically to her pregnant belly, which was now so huge it looked fit to burst at any moment.

My eyes felt as if they were bulging out of their sockets, but I tried my best to remain calm and composed in the face of such alarming and unexpected news.

‘Well, I don’t know what to say,’ I blushed. I could feel the colour rising in my cheeks in preparation for her inevitable explanation and confession.

‘You see, Nurse, I’m not proud of it, but I went out to a dance in Tarporley and got drunk. I was on those Cinzano and lemonades. Not used to ’em. I had a one-night stand and, trust my luck, I landed up with triplets! Can you believe it?’

She chuckled half-heartedly while I gaped open-mouthed and shook my head.

‘No, nor could I, especially when I missed my next period and worked out the dates. Mick had been away, you see, got a big job laying Tarmac on the new motorway in Lancaster. You won’t say anything, will ya, Nurse?’

I patted her hand and gave her a big smile. ‘Course not,’ I said. ‘Why would I? Looks like he loves you to bits. I wouldn’t dream of interfering. Now come on, get some sleep. Those babies could come any day now you’re thirty-five weeks pregnant.’

I was absolutely stunned by Geraldine’s revelation, and not altogether certain I’d done the right thing in playing down her infidelity. It wasn’t my place to judge her, of course, but now I felt complicit in the deceit and I wished she’d never confided in me. That said, I found it impossible to be cross with Geraldine. She was such a likeable woman, as down to earth as they come. Her secret was safe with me.

The following night I arrived for duty on the labour ward to find an ashen-faced Mick pacing the corridor and dragging urgently on a cigarette, his brow deeply furrowed. For an awful moment I feared he’d found out the terrible truth, but he brightened immediately when he saw me and said: ‘It’s very good to see you, Nurse.’

It seemed Geraldine was in labour, several days earlier than anticipated.

‘Look after her, won’t you, Nurse?’ Mick added, giving me a friendly wink. ‘She’s the love of my life, you know.’

His words brought a tear to my eye, but it was a happy tear. His sentiments put everything in perspective. He and Geraldine loved each other and they were stuck together like glue. Wasn’t that what mattered most? I thought so, and I dearly hoped so.

As Geraldine had been in hospital for practically two months we were well prepared for the triplets’ birth. The theatre was ready in case she needed a Caesarean section, but the consultant had decided to give her every opportunity to deliver the babies naturally, as that was the preferred option in the early Seventies, provided there were no complications. We had a team of staff briefed and raring to go, and there had been quite a buzz around the maternity unit for weeks now as we all looked forward to this moment.

I was very proud to have been chosen as one of the three midwives who would each deliver a triplet. It was unusual to have more than one midwife involved, but that was what the doctors had decided on this occasion. I was delighted to have a starring role in the proceedings, and I was also very pleased to have arrived for my shift in good time, while Geraldine was in the first stage, still labouring.

I quickly pinned on my cap, tied on a clean apron and gathered my notes before marching as briskly as my legs could carry me to the delivery room.

Geraldine spotted me the second I walked through the door. ‘Glad you’re here, Nurse!’ she roared between hefty contractions that made her face contort beyond recognition.

Also gathered were two other duty midwives, Jill and Sheila, two trainee doctors I had never met before and two nurses I recognised from theatre and the neonatal unit.

I watched intently as the consultant, Dr Cooper, listened with an ear trumpet for three babies’ heartbeats and announced to the room he was extremely pleased to report they all sounded strong and healthy.

My own heart rate was raised at the excitement of the occasion, but I wasn’t nervous. Geraldine was a model patient – that’s if you discount her frequent, ear-splitting cries of ‘Bloody hell!’ and ‘Flamin’ ’eck!’

She gestured for me to take her hand, and each time another contraction came she squeezed so hard I thought she’d cut off my circulation. We spent about two hours going through the same routine of screaming and hand squeezing and, as the labour increased, so too did the volume of Geraldine’s cries and the strength of her already vice-like grip.

To help her cope with the pain she sucked on gas and air, which was attached to a big cylinder labelled ‘Entonox’. We were ready to give her a shot of the painkiller Pethidine should she require more relief, but in the event her labour progressed so quickly and Geraldine was doing so well, there was no need. At about 11 p.m. the birth began in earnest, with the head of the first of the three babies visible, ready to be delivered.

‘I can see baby’s head. It’s time to push,’ I said.

‘About bloody time. Aaaaarrrghhhh!’ growled Geraldine, before pushing out baby number one beautifully, straight into my hands. It was an absolute joy to see she was a perfect little girl who was so fair she looked as bald as an egg.

As I set about cleaning the screaming baby, who was clearly in no need of resuscitation, I realised Dr Cooper had stepped in to deliver the second baby. He told us it was intent on coming out bottom-first, which wasn’t what we’d wanted. Of course, having no scanning equipment in those days and only using our hands to palpate the abdomen and feel the position of the babies, it had been very difficult to gauge accurately how the triplets were lying.

I glanced at my colleague Jill, who had been meant to deliver baby number two. She looked disappointed, but we all knew that a doctor had to deal with a breech birth in these circumstances. Midwives are there to deliver babies under normal conditions, and this was a complication in an already unusual pregnancy.

Somewhere amid Geraldine’s now blood-curdling screams and the hushed but firm instructions being issued by Dr Cooper, I heard the words: ‘Well done. It’s a boy!’

By now baby number three was obviously in a hurry to meet its siblings. ‘Cephalic’ I heard almost immediately, and breathed a sigh of relief. That meant this one was head first, thank goodness. ‘And another girl! Congratulations, Mrs Drew!’

I looked at Geraldine’s exhausted face and her eyes met mine. Often during a delivery the mother will seek out one individual for reassurance. Nowadays it is usually the husband, but with Mick still pacing the corridor outside, as expectant dads did back then, Geraldine looked to me in this room full of people.

‘Well done,’ I whispered. ‘You’ve done it!’

It was only then she allowed a smile to stretch across her face. Despite her brave banter, she had been as apprehensive as the rest of us about this tricky delivery. So much might have gone wrong. Three babies meant three times the potential problems – and some.

‘Are they all OK?’ Geraldine puffed as I helped clean the babies up and arrange them in three cots around her bed.

‘They sound it!’ I laughed as the trio struck up a hearty chorus. They were captivating, they really were. Each one was perfect and pink and utterly gorgeous. ‘And I can count thirty fingers and thirty toes,’ I added, looking adoringly at each one in turn. ‘They are wonderful! Shall I get Mick?’

‘Yes please,’ she nodded proudly.

I have never seen a man look as delighted and besotted as Mick did that day.

‘Well, what d’ya reckon?’ Geraldine asked as he stepped into the room, his dancing eyes not knowing which cot to peer into first.

‘I’m as chuffed as mint balls!’ he said, smothering Geraldine with kisses before going up to each cot in turn and cooing over his babies. ‘Chuffed as mint balls!’

It was wonderful to witness a show of such pure, unadulterated joy and love. My heart went out to the Drews. They were now responsible for six children under the age of seven. Geraldine had already told me that Mick’s wage only just supported them as a family of five, let alone eight. Now they would somehow have to find room for three more little mites in their small semi-detached house. With Geraldine not able to drive and certainly not able to afford a vehicle big enough for her family even if she wanted to, she would have to go everywhere on foot. She would be practically housebound, I realised, with a sudden pang of worry. How would they manage?

Looking at the Drews, who were now holding hands tenderly and gazing at their triplets through dewy eyes, you would never have guessed their world was anything less than perfect. The babies had been delivered safely and each one looked a picture of health. To them, nothing else mattered in that moment, and I was absolutely thrilled for them.

Geraldine and her babies spent ten more days with us. We placed three cots around her bed on the postnatal ward, and at night all three babies were taken to the nursery, where I would often feed one with a bottle while rocking the other two in their cots using my feet.

I felt sad when I finally said goodbye to Geraldine. Despite her smoking and cursing and despite what she had done behind her husband’s back, she was a very nice woman who had a heart of gold, and I knew I would miss her. I still felt uneasy about the deceit, of course. I desperately wanted things to work out for the Drew family and I couldn’t help worrying about what might happen if Mick ever discovered his wife’s guilty secret.

‘Daddy, baby Michael looks the spit of you!’ one of the young Drew boys had exclaimed during an evening visit. ‘Look at his big ears! He has your nose too!’

‘What do you think, Nurse?’ Mick said, directing a piercing gaze at me, which he held for longer than was comfortable.

‘Don’t ask me!’ I laughed, sounding rather too jolly and wishing myself far away. ‘All I know is you’re a very lucky man, Mr Drew,’ I added hastily as I busied myself writing up notes.

‘I know, and my wife’s a lucky girl,’ he said, giving me one of his twinkling winks and smiling a wide, knowing smile. ‘A very lucky girl indeed.’

He was a card all right, just like Geraldine. They made a good pair and I hoped they made it, I really did.

It wasn’t until I was heading home after my shift that something dawned on me. Maybe Mick was trying to tell me something that night? I wondered if he knew the truth all along, or at least suspected it, yet he loved his wife so much he wasn’t going to let it spoil a thing? He was a proud and staunch family man, perhaps so much so he was prepared to keep his wife’s secret and raise another man’s children. It was possible the only thing he wasn’t comfortable with was allowing the midwife to think she knew more than he did himself about his personal life.

‘A couple of cards all right,’ I chuckled to myself when the pieces of the puzzle fell into place in my mind. ‘Good luck to them.’

Preface

To this day, the story of Geraldine Drew and the birth of her triplets remains one of my all-time favourites. It encapsulates the role of a midwife as a professional assistant and confidante, whose ultimate aim is to help women deliver babies safely into the world, whatever the circumstances.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a midwife as ‘a nurse (typically a woman) who is trained to assist women in childbirth’. Over the decades, I have learned that there are many, many different ways a midwife can assist a woman in childbirth and, believe you me, plenty of them are not listed in midwifery textbooks!

When I started my nursing training in 1966 at the Manchester Royal Infirmary (MRI) I had no idea what I was letting myself in for, or even that I would become a midwife. I have since delivered more than 2,200 babies and I still tingle with excitement at every birth. Just feeling the warmth of a newborn’s head in your hands, that new life, there’s honestly nothing like it.

In 2010 I celebrated forty years as a qualified midwife, becoming Britain’s longest-serving midwife at the same hospital. Today, I marvel at how much, yet also how very little, has altered over the years. I’ve witnessed countless changes in the NHS and in midwifery practices, from the demise of the old Nightingale wards to incredible breakthroughs in pregnancy drugs and IVF. I’ve seen fashions for routine enemas, bottle-feeding and home births come and go, and I’ve watched the reluctant shuffle of dads into antenatal classes and delivery suites turn into a stampede.

There have been nine changes of government during my career, so I’m told, but I have never let politics get in the way of delivering babies. I have been very happy sailing along in the great old liner that is the NHS, quietly navigating sea changes in bureaucracy, funding, practices and guidelines. I’ve never aspired to rise up the ranks and become a manager. Delivering babies and striving to make every pregnant woman feel like the most important pregnant woman in the world is what I do best.

Last year I had the honour of being my daughter’s midwife during her pregnancy, and I am now a very proud grandmother. Baby Joel was born prematurely in July 2011 as I was working on this book and also mourning the death of my third husband, Peter.

So much has happened over the years that I could not fit my memoirs into one volume, and this book concentrates on the early years of my career in the late Sixties and early Seventies. That means the story of Joel’s nerve-racking birth, along with so many others, will have to wait.

As you read this first instalment, I will keep laughing and crying, remembering and writing.

Chapter One

‘It feels like we’re in the Army!’

‘My job is to make nice young ladies of you all,’ Sister Mary Francis proclaimed. She was the headmistress at the strict Harrytown High School I attended in Romiley, Cheshire, and this was a phrase I heard countless times from the age of seven.

The private, all-girls convent school was very highly regarded and, like many of my peers, I came from a comfortable, middle-class family. It was expected that we ‘young ladies’ would enter suitably respectable employment at the age of eighteen, which I gathered meant choosing between working in a bank, going into teaching or becoming a nurse.

I was seventeen years old when I was summoned to Sister Mary Francis’s imposing dark-wood office and asked the question: ‘Well, Linda, what do you propose to do next?’ Before I could answer, she tilted her head forward to peer at me over her small, round reading glasses and said gravely: ‘You are indeed a fine young lady, despite the one minor indiscretion we have thankfully overcome. I trust you have chosen wisely.’

‘I’m thinking of going into nursing,’ I replied meekly, blushing at her reference to my ‘indiscretion’. She meant the time I was caught breaking a cardinal rule and talking to boys on the bus. This had been seen as such a scandalous breach of conduct that a letter was sent home to my parents, warning of severe consequences should I ever compromise my reputation in such a way again.

‘Nursing is a good choice for you,’ Sister Mary Francis deemed. ‘But only the best will do for my girls. I want you to apply to the Manchester Royal Infirmary. It is a teaching hospital, and the most prestigious in the region. Please promise me, Linda, that you will always work hard for your living.’

I nodded obediently, grateful that Sister Mary Francis had not probed any deeper, as I had just three rather fragile reasons behind this big decision.

Number one: my best friend Sue Smith from school had an older sister called Wendy who was a nurse. She was always smiling when she told us tales about her job, and I thought she looked wonderful in her smart uniform. I admired her, and I wanted a uniform like hers.

Number two: my mum always said I was a caring person, telling me that I’d insisted on looking after my teddy bear right up to the age of eleven. I thought I’d be good at tucking patients into bed and giving them tea and sympathy.

Number three: I didn’t want to work in a bank and I didn’t want to teach. My parents never wanted me to work for the family business, even though their bakery shop near our home in Stalybridge was very successful. It was hard graft being self-employed, Mum always said. She wanted better for me.

Nursing it was to be, and that is how I found myself standing before Miss Morgan, Matron of the Manchester Royal Infirmary, in September 1966.

‘You must see me as your other mother!’ she boomed. I was eighteen years old and I had just started my three-year training course at the MRI, which was situated on Oxford Road, a mile and a half outside the city centre.

Though I knew next to nothing about nursing I had quickly cottoned on to one very important fact: Matron was like God, and her word was Gospel.

‘I want you to be able to talk to me at all times,’ Miss Morgan instructed forcefully, her extremely large bust somehow expanding further still as she snorted in her next breath. ‘You are my girls!’

I looked at her in horror. She seemed completely unapproachable and absolutely nothing like my own mother. My mum was so gentle-natured she practically had kindness dripping from her pores. Miss Morgan was a bulldozer in a bra by comparison. Her voice penetrated my eardrums with considerable force, and her facial expressions were as stiff as the large, starched white frill cap that was clamped on her head.

I nervously glanced from left to right to see how the other new girls in my group were reacting. There were thirty-six teenage girls in my intake, and we were divided into groups of six. As my name then was Linda Lawton, I’d been placed with two other student nurses whose surnames began with the letter L, as well as with three whose surnames began with M and P.

I took some small comfort from the fact Nessa Lawrence, Anne Lindsey, Jo Maudsley, Linda Mochri and Janice Price all looked as startled as I felt.

‘You will be taken down shortly to be measured for your new uniforms,’ Matron went on, forcing a rather frosty smile to her lips. I imagined her heart was probably in the right place, but she seemed oblivious to the fact she’d turned us into a group of baby rabbits caught in the glaring headlights that were her wide, all-seeing eyes.

‘Be warned, girls, that if I catch any of you shortening your uniform I will unpick the hem myself forthwith and restore it to its correct length, which is past your knee, on the calf.

‘Hair is to be clean and neat and worn completely off the collar, stocking seams are to be poker straight, and make-up and jewellery are strictly forbidden. Strictly forbidden!

‘You will require two pairs of brown lace-up shoes which are to shine like glass every day. Cleanliness is next to godliness, never forget that, girls!’

We listened attentively, scarcely daring to breathe lest we incur Matron’s wrath.

‘Furthermore,’ she went on, ‘I will not tolerate lateness, sloppiness or untidiness of any nature and I expect best behaviour at all times.

‘Good luck, girls,’ she added briskly, smoothing her hands down the front of her exceptionally well-pressed grey uniform. ‘Don’t forget you must come and talk to me at once about any concerns you may have. I am here to help you.’

Miss Morgan was clearly exempt from the make-up ban as she had thickly painted red lips, which she now stretched into the shape of a wide smile. Despite this she still managed to look incredibly intimidating as she waved us out of her office and instructed us to follow a grey-haired home sister down to the uniform store, a visit she hoped we would all ‘thoroughly enjoy’. Miss Morgan sounded sincere, but in that moment I felt a pang of real fear and homesickness.

The home sisters were typically older, unmarried sisters who had retired from working on the wards but ran the nurses’ home, and usually lived in. This one was glaring at us impatiently, which did nothing to ease my anxiety.

Dad had driven me in to Manchester and dropped me off earlier that day, and my small suitcase was still unopened. I’d felt as if I was going on an exciting adventure as we pulled up outside the grand red-brick façade of the enormous teaching hospital. It was opposite the sprawling university campus on Oxford Road, and I felt honoured to be entering the heart of such a vibrant, progressive community.

As I waved Dad off and joined the other eager-looking student nurses gathered in reception, I was buzzing with anticipation. I was actually going to be a nurse, and not just any nurse: I was going to be an MRI nurse!

Now, however, reality was rapidly starting to dawn. I felt lost and abandoned in this unfamiliar environment, with the imposing Miss Morgan thrust upon me as my ‘other mother’. Home was less than ten miles away, just a half-hour car ride east of Manchester. It was tantalisingly close, which only made me long for it all the more.

I’d been on just one previous visit to the MRI several months earlier after my letter of application, vetted and approved by Sister Mary Francis, was swiftly accepted. It was June 1966 when I was invited on a whistle-stop tour of the hospital, and when I met some of the other student nurses for the very first time.

Now, I realised, I had scarcely taken anything in. At the time I was preoccupied with finishing my A-levels and going on a summer holiday with my best friend Sue from school. We’d been invited to Beirut in the August, where my brother John, who was ten years older than me, worked as a journalist. It was a very safe and beautiful place to visit in 1966, and we were looking forward to exploring it, then spending two weeks sunning ourselves in Turkey afterwards.

When I got back from that first visit, my boyfriend Graham, who I’d been seeing for about a year, asked, ‘What was it like at the MRI?’

‘Well, there was nothing I disliked,’ I replied cheerfully. ‘I think I’ll like it,’ I added naïvely. ‘Shall we go to the cinema in Manchester tonight? I have to get used to the city before I live there!’

How I was ruing my blasé attitude. I was pitifully unprepared for my new life. I had absolutely no clue what I was letting myself in for and I had foolishly committed myself to the MRI for three long years of my life. That’s how long it took to qualify as a State Registered Nurse (SRN). Three whole years! I’d be twenty-one before I finished my training. It felt like a lifetime.

Walking along the windowless corridors on the first day of training, I felt like an inmate. Miss Morgan had said we would be ‘taken down’ to the uniform store, but I felt as if I was being taken down quite literally, to be incarcerated. There was no way out, and I saw nothing to cheer me up.

Plain, white walls were pitted with monochrome signs I didn’t understand. Metal trolleys were pushed by porters with faces as dull as cobbles. The hard floors appeared to have been scrubbed clean of any hint of colour. It was just like watching a boring old documentary on television, where everything was a grim shade of black and white.

Big doors loomed everywhere, swinging heavily on their hinges in the wake of white coats and pale green uniforms, which disappeared into goodness knows where. The world beyond the doors was, as yet, a complete mystery to me. The wards and clinics and theatres filled me with a mixture of curiosity and fear. I was in uncharted territory. That’s how the hospital seemed to me as I proceeded towards the uniform store with the other girls, marching rigidly on the left-hand side of the corridor, as instructed.

Turning a corner, I felt a gentle dig in the back of my ribs and whipped my head round to see that one of the girls in my group, Linda Mochri, was giving me a cheeky smile.

‘What d’ya think of our second Ma, hey Linda?’ she asked in a friendly Scottish brogue.

I sniggered and whispered behind my hand: ‘I don’t think I’d like to fall out with her!’

Linda screwed up her eyes and gave a little chuckle. ‘I might have to risk it if the uniform makes me look like a nun!’ she joked.

We continued in silence, fearful of receiving a ticking off from the home sister who was accompanying us, but thanks to Linda I felt ever so slightly less alone. We were all in the same boat, weren’t we? We ‘newbies’ would stick together and have a laugh and make the best of it, wouldn’t we?

Being measured for my uniform made me imagine I was joining the Army instead of the nursing profession. We had to stand in a stiff line like soldiers as we each took it in turns to have the tape measure wrapped around our bust, waist and hips. All the while we listened earnestly to a string of orders and instructions from the home sister.

‘You must wear your uniform at all times, even in school, though you must remove your apron during lessons.

‘You will each be provided with three brand new dresses and ten aprons. It is your duty to take good care of your clothing and to take pride in your appearance at all times.

‘As you are aware, the uniform consists of a light green dress with detachable white cuffs and collars and a white cap, which must be clean and stiffly starched at all times.

‘You will leave your dirty clothes in your named laundry bag outside your room once a week, and they will be taken away and laundered. It is your duty to collect your clean laundry from the uniform collection point.

‘You will be shown how to fold your hats correctly, don’t fret. You will soon be experts in the art. If you have not already done so you must purchase two pairs of brown lace-up shoes, and your stockings must be brown and seamed. Matron likes seams to be perfectly straight, and be aware she will check up on you without warning.’

As the day went on we were bombarded with more and more information, and my head began to ache. We were shown the stark schoolroom, which contained dark-wood desks, a full-sized skeleton and a dusty blackboard. Our daily routine was to begin at 8 a.m. prompt for lectures with Mr Tate, to whom we were briefly introduced. I scarcely took in a word he said because I was too busy taking in his demeanour. He had huge lips, wore a terrible green knitted tie and ill-fitting glasses, and had the worst comb-over you could ever imagine, with skinny strands of greying hair stretched desperately across his bald scalp. Odd, I thought. A very odd-looking man indeed.

We would spend our first eight-week ‘block’ based in the schoolroom, and classes would be punctuated with tours of the fourteen wards in the 400-bed hospital. I didn’t even know what some of the names of the wards meant, such as endocrinology and thoracic, let alone how to navigate my way through the three-floored maze to find them.

That first evening I sat on my single bed at the nurse’s home with all my day’s thoughts and fears clattering around inside my aching head. As students we all had to live in the nurses’ quarters adjacent to the hospital; there was no choice in the matter. The money for our board was taken out of our student wages before we received them, leaving us first years with £27 a month – not a bad sum to live on, I supposed.

This was the first time I had been alone all day, and I gulped as I sat on the unfamiliar bed, trying to absorb the huge step I was taking. I surveyed my new bedroom warily and felt my throat tighten. It was a large room with a wooden floor and a big fitted wardrobe, which was painted the same drab, off-white colour as the bare walls and had three hefty drawers underneath. I got up and tried to pull one of the drawers open, but found the task almost impossible. Puffing and panting, I eventually managed to heave the drawer free, feeling like a feeble little bird struggling to build a nest. I wanted to cry.

There was a stark white ceramic sink in one corner and a small dressing table with a chair in the other. My bed had two grey woollen blankets, and a starched counterpane lay across the top. I plumped my pillow and it felt stiff and scratchy to the touch, which made me even more miserable. To make myself feel better I took my John Lennon poster from my suitcase and stuck it on the wall above my bed. I knew it was against the rules to decorate the walls but I couldn’t really see what harm it could do, and I made a mental note to be careful not to damage the paint when I took it down in the future.

‘New linen will be left outside your door once a fortnight,’ the home sister had instructed. ‘You must strip your bed and leave your dirty laundry outside your door, in your laundry bag.’

She’d given us a brisk guided tour of the nurses’ accommodation earlier. ‘There are wooden blocks fitted to the inside of all of the windows,’ she told us in a matter-of-fact tone. ‘This is to stop intruders getting in.’

Sitting on my bed that evening, I looked over at the one small rain-smeared window and felt a film of tears mask my eyes. I was used to living in relative luxury, sheltered at my private convent school and cosseted by my parents in our comfortable suburban home. This was the first time in my whole life I had felt vulnerable – afraid, even. I’d imagined that after spending a month abroad in the summer I’d be absolutely fine living in Manchester. I was less than ten miles from home, but everything here seemed so alien to me.

Sue and I had stayed at my brother’s apartment in Beirut for two fun-filled weeks. He worked for United Press International and had a wonderful lifestyle. A cleaner came in every morning while Sue and I sunned ourselves by the pool. Afterwards we met John for lunch at the plush St George’s Hotel, and in the evenings he took us to fancy parties. I remembered how he smiled when we asked for Ovaltine at bedtime on our first night. ‘Why don’t you try a gin and tonic instead?’ he suggested. We did, and we never stopped giggling for the whole holiday.

Sue and I both felt so grown-up. We booked ourselves on a three-day excursion to Jerusalem, where I bought a beautiful leather-bound bible, and then we spent two weeks holidaying in Turkey with John’s Turkish wife Nevim, who looked after us really well. I was an independent woman of the world – or so I thought.

There was a rap on my door that made me jump. ‘Can I come in?’ a lovely Scottish voice sang, and I shot up gratefully and unlatched the door.

I knew it was Linda Mochri, and her voice instantly made my tears evaporate.

‘Of course you can!’ I said, and when I opened the door I was delighted to see she had Nessa, Anne, Jo and Janice in tow.

‘Your room’s the biggest, you lucky thing!’ Linda said as she lit a Marlboro cigarette and sat cross-legged on the end of my bed. The other girls filed in and found themselves a place to sit. Nessa was last through the door and she settled on the scratched wooden floor, folding her enviably long legs beneath her.

Janice also lit a cigarette, which she pulled from a fashionable lacquered case that covered her pack of twenty. She looked confident to the point of cockiness as she took a long drag.

‘How are you all settling in, then?’ she asked, after blowing out a plume of smoke. She looked at each of us in turn.

‘Feels like we’re in the Army!’ Linda snorted. ‘Curfew at 11 p.m., girls!’ she said, mimicking the home sister’s briefing from earlier in the day. ‘Any nurses not home by 11 p.m. will have Matron to deal with and will lose the right to request a late pass! Late passes allow you to be home by midnight – but be warned, you have to earn them, girls!’

We fell about laughing and, with the ice broken, we began to gently pick over the long day we’d had.

‘What do you think of our tutor?’ Anne asked with a mischievous glint in her eye. Anne was quite plump, with one of those smiley, rosy faces larger girls often have.

We all chipped in with our views on Mr Tate, who for the first two months would teach us anatomy, physiology and basic nursing techniques in the schoolroom. After that he would continue to teach us between our practical training and placements on the wards.

‘He’s the strangest-looking man I’ve ever seen,’ I volunteered with a shy giggle.

This was no exaggeration. Everyone admitted they had been taken aback at his appearance, particularly his precarious-looking comb-over.

‘I dread to think what he looks like when the wind blows,’ chuckled Jo.

She and Janice were two of a kind, I thought. Both exuded self-confidence, while Linda and Anne were definitely the jokers in the pack. Nessa seemed more like me. She was softly spoken and came from Cheadle, not too far from where I grew up. We were the only two who didn’t smoke, and when Nessa contributed something to the conversation it usually struck a chord with me.

‘Is it just me or does anyone else think the blocks on the windows are a bit alarming?’ she ventured.

‘I hate them!’ I admitted. ‘It makes me think a mad man is going to break in at any moment.’

‘Will you listen to yerself!’ Linda mocked gently. ‘We’re holed up here like prison inmates. I reckon the blocks are there to stop us escaping rather than to stop men breaking in!’

We all laughed again.

‘What shall we dissect next?’ Anne asked.

‘Bathrooms!’ Jo and Janice chimed in unison, and we all bemoaned the fact we had one bath and toilet to share between twelve of us.

The nurses’ quarters were shaped like a letter ‘H’ and my new-found friends and I were grouped together down one leg of the ‘H’. It was pot-luck that I got the biggest room. We were all allocated a number and I happened to be student nurse number six, which meant I was allocated the sixth room on the corridor.

‘It’s certainly not what I’m used to,’ Anne said wistfully, and we shared snippets of our lives back home.

With the exception of Linda Mochri we had all grown up in the region. Linda’s family had relocated from Scotland because her mother was ill with cancer, and the best treatment was available to her in the North West of England. Apart from that, we seemed to have a fair amount in common, all having come from good schools and supportive families. I learned that Linda, Jo and Janice had long-term boyfriends like me, but Nessa and Anne did not.

‘This is certainly a far cry from what any of us are used to,’ Janice declared, wrinkling up her nose.

I couldn’t have agreed more. As a child I moved house frequently, always to somewhere bigger and better as Lawton’s Confectioners went from strength to strength. My parents sold teacakes, puff pastries, parkin, pies, bread and apple tarts from their double-fronted shop on the High Street in Stalybridge, all hand-made in the bake-house by my father, John.

He was a gentleman who ‘never wanted to be on the front row’, as my mother Lillian often said. That was absolutely true. You couldn’t have met a kinder or more unassuming man, and he never once so much as raised his voice to me. My mother wore the trousers in their relationship and was also the one who controlled the business, but that didn’t stop her being a very kind and caring mum.

My brother John and I wanted for absolutely nothing. The fine career in journalism he’d carved out for himself made both my parents very proud and the two of us were the apples of our parents’ eyes, in our own distinct ways.

I shared a little bit about my family background with the other girls, and also told them about Graham, who I’d been going out with for about a year.

‘I love dancing and we met at the Palais in Ashton last year when I went to a dance with my old school friend Sue,’ I told them. ‘He works as a car salesman and drives a little blue bubble car.’

‘Lucky you! Is he good-looking?’ Janice asked cheekily.

‘Well, I think so,’ I blushed. ‘He’s got blond hair and blue eyes and wears very nice clothes.’

‘Ooooh!’ Anne chucked. ‘I’m jealous!’

‘Come on!’ Jo said, sparing me any further interrogation as she stood up and stubbed out her cigarette in my sink, having failed to locate an ashtray. ‘We’ve got an early start tomorrow.’ All the other girls took the cue and shuffled to the door.

As I bid them goodnight and got myself ready for bed I couldn’t help thinking about my bedroom at home with its soft cotton sheets, plush wool carpet and pretty pictures hung against the stylish floral wallpaper I’d been allowed to pick out from the chic Arighi Bianchi store in Macclesfield. I longed to be back in my bed at home, and for my father to knock gently on my door to wake me up in the morning, as he always did. But then, I thought to myself, what would I do all day?

Here I felt terribly homesick despite the girls’ comforting chitchat, but I realised I also felt very much alive and stimulated. My head was filled with hundreds of questions about what tomorrow would bring, and my emotions were on red alert. This experience was unsettling, but it was undeniably exciting too.

It had been an exhausting day, and if my tiredness hadn’t knocked me out I’m pretty sure the thick clouds of smoke the girls left behind in my room would have done. I had one of Graham’s handkerchiefs, which smelled of his Brut aftershave, and I placed it on my scratchy pillowcase for comfort, and to block out the smell of smoke. I didn’t stir until my alarm clock rang at 7.15 a.m., heralding my first full day as a student nurse.

Chapter Two

‘I really am becoming an MRI nurse!’

‘A patient will not die if you forget to take their blood pressure,’ Sister Craddock pealed in her rich Welsh accent as she escorted us from the schoolroom, ‘but dirty floors breed bacteria, and bacteria kill.’

Sister Craddock had very curly red hair and a face dotted all over with freckles. Her figure was as round and curvy as her tightly sprung ringlets, and I was as captivated by her appearance as I was by her staunch philosophy on hygiene.

We’d spent the morning studying anatomy with Mr Tate, and my head was brimming with medical facts. I’d enjoyed the lessons and found them easy to follow, because I’d studied chemistry and biology for my A-levels. I pictured myself using my new knowledge, hopefully in the not-too-distant future, to help me bandage a wrist or give a patient an injection. The thought was nerve-racking yet exhilarating.

‘Cleanliness is next to godliness,’ Sister Craddock chimed, echoing Miss Morgan’s words on our very first day here. Spinning on her tightly laced brogues, she looked each of us in the eye one by one as she warned very seriously: ‘As a nurse, it is imperative never, ever to forget that.’

This was clearly very important at the MRI. We were student nurses, not cleaners, but I figured I’d better listen as attentively to Sister Craddock as I did to Mr Tate. ‘Cleanliness is next to godliness.’ I let the phrase settle in my head, wondering what Sister Mary Francis would make of it. In all my years at my convent school I had heard hundreds, if not thousands, of references to ‘godliness’ but I did not recall that particular phrase. However, I had a pretty good idea I’d be remembering it regularly from now on.

Sister Craddock led a small group of us down several corridors and towards one of the urology wards, continuing to lecture us about hygiene.

‘What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger,’ she said, and I wondered what she could mean by that. Were the cleaning fluids dangerous? What could possibly threaten us here in the hospital? I was getting used to her loud, melodic voice now and my mind was wandering.

As we approached the ward a sudden, silly image flashed into my head. I imagined Sister Craddock stepping up on stage and belting out the song ‘Goldfinger’. Shirley Bassey was Welsh, wasn’t she? Sister Craddock didn’t look anything like Shirley Bassey but she certainly sounded like her. I could just picture her singing her heart out, flinging her arms wide at her grand finale, then afterwards pointing at the audience triumphantly and declaring: ‘What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger, ladies and gentlemen …’

‘Cleanliness is of the utmost importance on the wards, and to maintain our high standards is essential.’ Sister Craddock’s stern words hauled me back into the moment. Images of sequins and stage lights were extinguished in a flash, replaced by thoughts of dusting cloths, mops, buckets and disinfectant. I listened earnestly.

‘We have Nightingale wards here, girls, and if she were alive I would want Florence Nightingale herself to be proud of the cleanliness of them.’

I knew the large, open-plan wards were named after Florence Nightingale because she pioneered their design, but if I’m perfectly honest that was as much as I knew about them, despite their famous namesake. I was curious to find out more.

Sister Craddock pushed her soft bulk through a set of double swing doors, giving us our first glimpse of ‘her’ ward. The smell of cleaning fluid made my nostrils tingle as I stepped into this new territory. ‘Follow me, girls,’ she instructed. ‘I will give you a brief tour of the ward. Please be respectful of patients. No talking. I will do the talking.’

We stood in the first section of the ward, which Sister Craddock explained had a kitchen and a double side room to the left, and sister’s office, linen cupboards and two single side rooms to the right, which we were not invited to enter. Before us stood another set of swing doors, which led into the main part of the ward. We filed gingerly through, eyes and ears wide open.

Twelve beds lined each side of the vast ward, all occupied by ladies in varying stages of sleep who were swathed in flannelette nightgowns and knitted bed jackets. Most looked cosily middle-aged and some wore hairnets and sucked their gums as they surveyed us curiously but courteously.

There was something slightly surreal about the scene that I couldn’t quite put my finger on. One or two women were a bit younger and more fashionable than the others, with floral-print nightgowns and bobbed hair, yet there was an unmistakable correlation between them all.

Down the middle of the ward stood the night sister’s table, covered in green baize and with a large lamp hanging above it. At night, we were informed, a green cloth was placed over the lamp to create an air of calm and promote restful sleep. Beyond it, but also in the centre section of the ward, was a store cupboard plus a metal trolley housing a sterilising unit, and finally the patient’s long wooden dining table.

A sluice room, toilets and a bathroom were situated in the far right-hand corner of the ward, behind bed thirteen. Under the windows at the very back of the ward there was a small television, a few Draylon-covered armchairs and a low coffee table with a neat pile of women’s magazines on it. There was also a round, black ashtray, which had a cover. I’d seen one like it before and knew that when you pressed the button on top the ash would spin cleanly out of sight.

Sister Craddock’s voice sang on as I took in the scene. ‘There are twenty-eight beds in all; four in the side rooms and twenty-four in the main ward. Each ward is run by one sister, six to eight staff nurses and between ten and sixteen student nurses working around the clock. Shifts run from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m., 1.30 p.m. to 9 p.m. and 9 p.m. to 7.30 a.m. Jobs are allocated at each shift change and routines must be strictly adhered to.’

As Sister Craddock spoke, a penny slowly dropped for me. I looked at the twelve beds lined up along each white-painted wall and realised how perfectly arranged they were.

‘The ward has to be clean, neat and tidy at all times,’ the Welsh voice continued. ‘Patients are washed and have their beds changed every day. Bedding must be fitted exactly the same way each day, with enveloped corners on bottom sheets, pillowcase ends facing away from the doors and perfectly folded counterpanes on top of the blankets. You will receive precise instruction in bed-making procedures in due course. Please remember always to pull the top sheet up a little to make room for the toes, and to leave the counterpanes hanging at the sides, for neatness. The wheels of the bed must all point in the same direction, and nothing is to be left lying around on the tops of the lockers.’

That was it. The immaculate presentation of the beds and furniture was what made the ward appear slightly surreal. I had never seen such a well-ordered room in my life before, and I marvelled at how a ward full of sick women in a mishmash of nighties and hair nets could look so methodically well ordered.

The crisp cotton counterpanes were all pale green to match the curtains that could be pulled around each bed. Every bedside locker had a little white bag taped to it for rubbish, leaving the top clear for a jug of fresh drinking water and a glass. Some patients had a vase of flowers on their locker-top or one or two get well cards.

‘Only one bunch of flowers is permitted per patient,’ Sister Craddock cautioned, ‘and it must be removed to the bathroom at night.’

We nodded in unison. Rudimentary biology told me this had something to do with plants releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere at night.

‘Smoking is permitted on the ward but not encouraged.’ We nodded in agreement again. This seemed perfectly reasonable.

‘Orderlies damp dust every surface in the ward daily: windowsills, lockers, bed frames and furniture. Domestics clean the floors, toilets, bathroom, kitchen and sister’s office, and twice a week they pull out the beds and clean behind them, thoroughly.

‘As a student nurse you will be expected to attend to the general good hygiene of the patients and help maintain the high standards of cleanliness required on the wards. It has been said that you could eat your dinner off the floor of my ward, and that is how it must always be. Please always ensure that even the wheels of the bed are gleaming and, of course, neatly aligned after cleaning. If ever you find yourself with a spare moment, use it to pick up a cloth and damp dust. There is always a surface to be dusted and cleaned, and there is no room here at the MRI for nurses who are slothful or slipshod.’

I watched a sympathetic-looking nurse plump up an elderly patient’s pillow and fill her glass with fresh water. The patient smiled at the nurse as if she was an angel, and the nurse smiled back, explaining courteously that it was time for the patient’s daily injection. The nurse must have been a third year, as she had three stripes of white bias binding on the sleeve of her uniform.

I looked at her in awe and admiration, noting that her bedside manner was as impeccable as her uniform. I wanted to make patients feel better too. I wanted to give them their medicine along with a warm smile. I wanted to be just like that nurse.

A few days later I went to the uniform store with Linda and Nessa, where we were each handed a hessian laundry sack with our names printed neatly across the top in black marker pen. Inside we found our brand new uniforms: three light green dresses made of a sturdy cotton which felt stiff, like new denim, plus ten aprons, three detachable collars and cuffs and a rectangle of white cotton. Sister Craddock deftly demonstrated how to craft the cotton into a perfect cap.

The three of us exchanged knowing glances as we signed for our uniforms and acknowledged the rigid rules about laundering them. This was the moment we’d been looking forward to above all else.

‘I can’t wait to try this on,’ Nessa whispered shyly to me.

‘Me too,’ I said. ‘I hate walking around the hospital in mufti.’

Linda chuckled. ‘Hark at you!’ she teased. ‘A week ago you didn’t even know what the word meant!’

My cheeks reddened. It was true. I’d had no idea nurses used the term ‘mufti’ when referring to their ‘civvies’ or ordinary clothes, but I’d heard it so many times since our arrival that it had slipped into my vocabulary without me even realising.

‘We’re going to be proper nurses now,’ I grinned, picking up my prized laundry bag. ‘We have to use the correct language!’

We carried our uniforms back to the nurses’ home with some ceremony, and all agreed to meet in my room for a ‘fashion parade’ before tea.

My mum had taken me on a shopping trip to Manchester a few weeks earlier and bought me two pairs of comfortable brown lace-up brogues in Freeman Hardy Willis. We had tea and scones with jam and cream in Kendals department store before visiting its grand lingerie section, where she bought me two suspender belts with metal clasps and seven pairs of brown, 30-denier Pretty Polly seamed stockings.

Now I took the underwear out of its tissue wrappers for the first time, and set about clipping, buttoning and lacing myself into my complete nurse’s uniform. I was beside myself with excitement as I pulled on my dress and attached its crisp white cuffs and collar, which had to be buttoned onto the dress. Next I used half a dozen brand new kirby grips to pin my neatly folded cap on top of my hair, which I had scraped back off my face and fixed in a tight bun using several brown elastic bands.

Finally, I placed my stiff white apron over my dress. It was huge! The lower part amply covered my wide skirt, which reached almost halfway down my calves, and the two enormous front flaps that pulled up and over each shoulder came so high they covered half of my neck. The wide straps had to cross over my shoulderblades before being brought back round and attached with a thick safety pin in front of my waist. What a procedure!

I turned and faced myself in the vanity mirror above my washbasin. It was a moment I’ll never forget. I thought of Sue’s sister Wendy, whose uniform I’d always coveted. I thought of all the nurses I’d been impressed by at the hospital. I pictured them soothing brows, pushing trolleys, calming anxious relatives and offering tea in pale green cups and saucers that matched their dresses. Now, in this moment, I saw myself amongst their ranks. ‘I really am becoming an MRI nurse!’ I said to my surprised reflection.

When Nessa and Linda arrived a few minutes later we all shrieked and hugged each other.

‘Will you look at the state of us!’ Linda exclaimed as we ‘oohed’ and ‘aahed’ over each other like bridesmaids before a wedding.

Nessa and I both knew she was feeling exactly the same as us, though: pleased as punch and bubbling with pride.

Sharing such exciting new experiences with the other girls helped me through the first few weeks, although I still felt horribly homesick. Graham visited a couple of times a week, turning up in the hospital car park in his bubble car and taking me into Manchester for a cup of coffee and a chat. Once or twice he drove me home to visit my parents at the weekends, too, but I’m not sure that helped my feelings of homesickness as I always found it very hard to say goodbye to them.

Several weeks on, after my eight-week school-based ‘block’ was complete, I reported for ward duty for the first time with Sister Craddock, who paired me with an efficient-looking third-year student called Maggie. I was assured Maggie would ably instruct me in the arts of completing a bedpan and bottle round and giving bed baths, and I couldn’t wait to get started.

‘Most patients can manage by themselves if you draw the curtain and give them a bottle or a bedpan,’ Maggie said brightly, which immediately put me at my ease. She had already dished out half a dozen stainless steel bedpans, and she asked me to follow her round the ward and help her collect them by placing a paper cover on them and loading them on a trolley.

‘Nobody likes this job,’ she said as we went into the sluice. ‘The golden rule is to look the other way and stand back so you don’t splatter your apron.’

There was a porcelain sink on the back wall, into which Maggie tipped the contents of the pans before flushing the metal chain that was dangling beside it. The smell that rose up my nostrils as the urine and faeces were washed away made me heave, and I held my breath.

Maggie turned on the taps on either side of the sink and swilled out the pans before loading them one at a time into a sterilising unit that looked like a narrow metal washing machine. Each bedpan was blasted with boiling, steamy water before Maggie removed it with a thick linen cloth and placed it on a clean trolley ready for the next bedpan round.

‘The trick is to get it over and done with as quickly as you can,’ Maggie said. ‘Grit your teeth and just do it. If there’s one thing I’ve learned it’s that bedpans won’t clean themselves and, believe me, the smell gets worse the longer you leave it!’

I felt at ease with Maggie and hung on her every word, eager to learn from her experience. Our next task was to perform a bed bath on Mr Finch.

‘He’s a good one to start with as he lives up to his name and is as light as a bird,’ Maggie whispered as we approached his bed.

‘Good day, Nurses!’ Mr Finch beamed as Maggie pushed a trolley beside his bed and I closed the curtains around him. ‘Is it bathtime? Oh, go on then, if y’insist!’

Mr Finch put down his Daily Mirror and rubbed his hands together cheekily, eyes glinting.

‘He’s just teasing,’ Maggie said. ‘Aren’t you, Mr Finch?’

‘I am indeed,’ he tittered. ‘I’m a good boy really.’

Maggie caught my eye and winked, but I still felt slightly nervous. Mr Finch looked a bit scruffy, with nicotine-stained fingers and blackened teeth, and I shivered as I wondered what we might have to deal with under the sheets.

‘Any trouble from him, Nurse Lawton, and we’ll make sure the water is ice cold next time,’ Maggie said in an exaggerated whisper.

On the trolley Maggie had a pot of zinc and castor oil cream, a metal bowl filled with warm water and a tin of talcum powder. Mr Finch reached into his locker and produced a toilet bag containing a bar of Palmolive soap, two grey flannels and a small, thin towel.

Maggie showed me how to strip the counterpane back and pull the blanket off the patient and over an A-shaped frame she had placed at the foot of the bed.

‘Keep the top sheet in place and work underneath it as best you can,’ Maggie said quietly. ‘That’s the privacy guard.’

She demonstrated by washing and drying Mr Finch’s face first and moving on to his arms, chest and underarms without exposing an inch of flesh unnecessarily.

‘Ooh, that’s grand, Nurse,’ Mr Finch commented. ‘You’re right good at this!’

Next I helped turn Mr Finch on his side, so Maggie could wash down his back and I could dry it. He certainly was as light as a bird. He was skin and bone, in fact, and I realised he looked rather like the old man in the television comedy Steptoe and Son, which amused me.

‘Would you wash your private bits?’ Maggie said, making it sound as though she was posing a question when in actual fact she was instructing Mr Finch politely to do so.

‘Course,’ he said. ‘I tell ye what, it’s a damn sight easier t’ get m’self clean nowadays. Used to be murder when I were down the pit.’

It turned out that Mr Finch was born at the turn of the century and had worked nearly all his life at the Astley Green Colliery in Wigan, mining coal for decades until his retirement a few years earlier. He had seven children and seventeen grandchildren, and had served in both world wars.

As Maggie and I rolled him onto each side again so we could strip and re-make the bed beneath him, I thought how silly I was to have been nervous about him, and how unkind I was to have assumed he might be smelly or uncouth, just because he was old and had spent his life working his fingers to the bone.

I loved getting to know such interesting folk and I soon realised that once people are stripped bare in a hospital bed, that’s when you find out who they really are. This realisation struck me as so profound that I wrote it down in my notebook when I returned to my room after tea, because I never wanted to forget it. As I did so, I realised with some satisfaction that despite still being plagued by homesickness, and despite feeling mentally and physically drained at the end of the day, I was doing my very best and I was slowly starting to find my feet.

I fell into an extremely deep sleep that night. Sister Mary Francis would have called it the ‘sleep of the just’, but my much-needed slumber was suddenly interrupted when an alarm bell rang out. In my dream I saw a ghostly-white patient desperately pressing a red emergency buzzer. I couldn’t see the patient’s face and I didn’t know which ward he was on or what was wrong with him. I could see him holding out his hands to me, but I couldn’t get close enough to help him because I was stuck behind a pile of textbooks that towered higher and higher the more I tried to move forwards. Physiology. Anatomy. Dietetics. Bacteriology. The words swarmed, distorting my vision.

‘Wake up, Linda! Get up quick!’ It was Anne’s voice, and she was hammering on my door. ‘There’s a fire! Get up!’

I stumbled out of bed, my heart thumping. The alarm in my dream suddenly got louder and louder. My door was open now and I could see nurses running towards the emergency exit along the corridor. The fire alarm was blasting out as I grabbed my dressing gown and ran, barefoot, into the arms of a burly fireman.

‘Steady now!’ he grinned. ‘There’s no need to panic. Just make your way outside calmly and we should be able to get you back inside in no time at all.’

We were told a small fire had broken out on the opposite side of the nurses’ home, which was soon contained. This news travelled quickly around the car park, where I stood shivering in my nightie and dressing gown, still feeling drugged by sleep. Eventually another very handsome fireman led me back to my room, which he was in the process of checking over when the home sister stuck her nose round my door.

‘See that you remove that poster in the morning,’ she said huffily, pointing to my beloved black and white John Lennon portrait taped boldly above my bed. ‘You know quite well it is forbidden to decorate the walls.’

The fireman flashed me a dazzling smile and rolled his eyes behind her back before wishing me a very good night.

‘Do you know, I think I’ll always have a soft spot for firemen,’ I told Anne dreamily at breakfast the next morning.

‘All the more reason to work hard,’ Anne replied with a wink. ‘Everyone knows firemen have a soft spot for nurses, too.’

‘You’re right,’ I smiled. ‘Perhaps I’ve chosen the right career after all!’

Chapter Three

‘I didn’t expect to be looking after people who are actually ill’

‘Lawton, attend to Mrs Roache in bed thirteen,’ Sister Bridie ordered. I hated the way she addressed us by our surnames, as if we were in the Army. I leapt to attention, nevertheless.

I was now a good few months into my first year of training. So far I’d had a trouble-free start to my nursing career. Soon after the eight weeks of study with Mr Tate, which were punctuated by visits to wards and units, I completed my first placement, which happened to be at the eye hospital over the road in Nelson Street.

We had no say in where we were sent for work experience, but I had no complaints and was quite happy dishing out eye drops, wiping down lockers and fetching cups of tea for patients, while at the same time learning how to sterilise equipment, organise the linen cupboard and generally keep Sister happy.

The only part of the work that worried me at the eye hospital was using the sterilising equipment. The machine was different to the bedpan steriliser I’d become accustomed to operating in the sluices at the main hospital. This one stood on a substantial trolley that was positioned right in the middle of the ward. It looked harmless enough, shaped like a small stainless-steel oven, but it hissed and bubbled as loudly as a witch’s cauldron.

I’d seen other nurses adeptly sterilising kidney bowls, syringes and needles, seemingly oblivious to the dangers of the swirling clouds of hot steam the contraption emitted whenever it was opened, but I was scared to death the first time I had to operate it by myself, jumping back in fright as the sweltering steam billowed into my face. I practically threw the instruments in, pulling my hand away and slamming the door shut in record time. It was a miracle I hadn’t been burned, especially as I had to repeat the process in reverse five minutes later, retrieving my poker-hot equipment with a pair of Cheatle forceps.

Needless to say, I soon got used to the steriliser, and by the time I left the eye unit I think I could have operated it in my sleep. My next placement was to be on Sister Bridie’s surgical ward.

‘Are you looking forward to it?’ Graham asked me the night before I was to start there, when he picked me up in his car and took me out for a coffee at a little snack bar in Piccadilly Gardens, up near the station.

‘Oh yes,’ I replied. ‘Very much so. The eye unit was good experience but it wasn’t exactly exciting.’ The fierce steriliser had been the only thing that made my pulse quicken. ‘I’m ready for the next challenge. A surgical ward should be very interesting. It’s a female ward and I expect women need surgery for all sorts of reasons. It’ll be good to deal with more than just eyes.’

‘That’s my little nurse!’ Graham said encouragingly.

‘I’m a bit worried about Sister Bridie, though,’ I admitted. ‘She’s Irish and a spinster, so I hear, and she seems terribly strict and bossy.’

‘Don’t fret. You were worried about the Matron to begin with,’ Graham reminded me, ‘and I’ve hardly heard you mention her since.’

‘That’s true,’ I said thoughtfully. ‘I guess I’ve learned that Miss Morgan leaves you alone as long as you keep your head, and your skirt length, down!’

‘Glad to hear it,’ he smiled.

‘Besides, you always know when Matron is on the warpath, as word spreads like Chinese whispers. “Matron’s coming, pass it on,” we say, and usually the entire ward is on best behaviour before she has set foot through the main doors.’

Sister Bridie worried me more, I realised. ‘I’ll be seeing her on a daily basis on the surgical ward, come what may. I’ve heard she used to be on the men’s cardiac ward, and she shouted so loudly at the student nurses that she nearly gave the patients another heart attack.’

Graham laughed and I joined in, seeing through his eyes how funny this was. He was a marvellous help to me. Despite the camaraderie I shared with Linda and the other girls and the endless encouragement offered by my mum on the phone and on my occasional weekend visits home, it was Graham who kept me going, always willing to drive up to the hospital two or even three times a week to see me and let me unload about my day.

Sometimes I cried in his arms as we huddled together in the hospital car park, because I was tired out and I missed him and my home so much. Graham always provided a good reason for me to keep my chin up and carry on. ‘Think how you’ll feel when you’re a qualified SRN,’ he would say. ‘We’ll be able to get married and get a place of our own! You’ve come this far. You can do it, Linda. I’m so proud of you. You were made for this job.’

Now he commented: ‘I can’t imagine you giving Sister Bridie any reason whatsoever to shout at you.’

I hoped he was right, and his words helped set my mind at ease a little. All I had to do was obey orders and work hard, and I had nothing to fear. ‘What doesn’t kill me will make me stronger,’ I thought.

Graham also used to chat to me about events in the news and life outside the hospital, which helped to put things in perspective. I was so wrapped up in my own life I hardly ever took time to read a newspaper. Sometimes I didn’t even breathe fresh air for days on end, as the nurses’ home was attached to the main hospital by a covered walkway. Graham was my reality check, my link to the outside world.

‘Life is full of ups and downs, Linda,’ he said. ‘You have to take the rough with the smooth. Look at it like this. One minute the country is on a huge high, ruling the world with the football. The next, something terrible happens, like the Aberfan disaster. That’s life.’

It was just a few months since England had won the World Cup in the summer of 1966. I’m not a football fan, but I remembered Graham proudly telling me that Geoff Hurst, our hat-trick-scoring striker, was a local man who had been born in Ashton. Then in October the terrible Aberfan tragedy had united the country in the most dreadful grief. More than 100 children perished in that Welsh village when a slag heap collapsed on their school.

Life can be very cruel, and plenty of people had it a lot harder than me; that was an absolute certainty. In the big scheme of things, Sister Bridie’s harsh tongue was scarcely a hardship, and I resolved to do my very best under her watchful eye.

The night before my placement on the surgical ward began I noted in my diary that, thanks to my gentle introduction to basic nursing at the eye unit, as well as Graham’s words of wisdom and encouragement, I was feeling much more settled, and my confidence was slowly building.

The hospital and nurses’ home are now very familiar, and the strict regimes bring a sense of order and security, which I find comforting. Graham hasn’t actually ever proposed to me properly, but I like it when he suggests we’ll get married one day, and settle down. I would like that very much. I have learned that I prize security over uncertainty, and I want to pass my exams and qualify, because then my future will be set.

‘Lawton, attend to Mrs Roache in bed thirteen,’ Sister Bridie repeated impatiently, even though I was already picking up the notes to obey the order.

‘Yes, Sister,’ I said politely, giving her a nod. ‘Right away, Sister.’

I thought about being strong and making Graham proud as I strode to the far end of the surgical ward. I didn’t want to make any mistakes here. Sister Bridie had split purple veins etched across her grey complexion. Her silver hair was wrapped in a tight bun and a single white whisker protruded from a stone-like mole on her chin. She was as round and squat as a concrete mixer, and when she barked orders it felt as if she was spitting gravel at me. Sister Bridie was not a person I wanted to cross.

I hadn’t been prepared for the strong smell on the surgical ward, like nothing I’d ever encountered before. It clung in the air, and I found myself trying to take short, shallow breaths through my nose so as not to experience the full stench. Breathing like that made me tense my neck, and I could feel my starched white collar tighten around my throat, making me slightly light-headed. I remembered Janice telling us how she had embarrassed herself by gagging violently in front of the patients when she had to collect used bedpans on her first placement, but this smell was different and at first I couldn’t identify it.

I could hear trolleys rattling hurriedly past, Sister Bridie pebbling other nurses with orders and the unmistakable, upsetting sound of ladies crying out in pain. Against this background noise, all I could think about was the inescapable smell sticking to every pore on my skin. It made me clench my insides, to try and stop the smell getting through to me.

Mrs Roache was lying on her back with her right leg in traction. She had been hit by a speeding car as she crossed the Stretford Road in Hulme to collect her pension, and her thigh bone was very badly smashed. The old lady was on powerful drugs to help her cope with the considerable pain. Her leg had been dressed and strapped into what I recognised as a Thomas splint, which ran from beneath her pelvis right down to her ankle. Poor soul, I thought. She looked a sorry sight, propped up on top of her bedclothes, her blue-rinsed hair still matted into an ugly gash in her scalp.