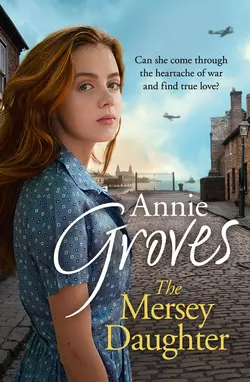

The Mersey Daughter: A heartwarming Saga full of tears and triumph

Annie Groves

The brand new Wartime drama novel from bestselling author Annie Groves, perfect for fans of Christmas on the Mersey and Child of the Mersey.Rita Kennedy has finally seen through her good-for-nothing husband, Charlie. Now he’s gone AWOL with his fancy woman and left her at the mercy of the local gossips. Her future is full of uncertainty and the only thing that keeps her going is knowing that her children are safe from the Luftwaffe – and the letters that she receives from Jack Callaghan, her childhood sweetheart – but a life together can is just a distant fantasy.Meanwhile, Kitty Callaghan has joined the WRENS and it’s opened up a whole new world. But despite finding romance with a handsome doctor, she still can’t forget Frank Feeny, the brave officer from Empire Street who still inhabits her dreams.As the bombs rain down on Liverpool, Rita and Kitty must face heartache and sorrow as they pray for the sun to shine on the Mersey once again.

Copyright (#u7a8e88bb-c8ea-5f18-be1a-76cec90b962c)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins 2017

Copyright © Annie Groves 2017

Cover layout design © Annie Groves 2017

Cover photography © Cover design by Claire Ward © HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2017

Cover photographs © Rajkumar Singh / plainpicture (woman), Simon Baylis / Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com) (street scene).

Annie Groves asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007550845

Ebook Edition © February 2017 ISBN: 9780007550852

Version: 2017-10-27

Table of Contents

Cover (#u2e365569-4b74-53f2-bb9b-8bc86f8de6bd)

Title Page (#u5581f619-08e0-5749-9104-9f5ad84bc19d)

Copyright (#u992e75aa-52bb-59f9-a3f6-5b0dfe1639e9)

Part One (#uc1f3286a-bf0e-5835-9651-8419c3718f3b)

Chapter One (#u119dd917-a913-57c2-9a7c-ace95472453b)

Chapter Two (#udd04a150-24bc-52a3-86f2-a6e0bec2845c)

Chapter Three (#u502151a6-1462-5bd2-9268-a348cfd29ac3)

Chapter Four (#u2acabab8-cd42-5c16-9a1f-4c25bda36c46)

Chapter Five (#uef096a9c-2fce-5dba-aa3a-3e4b1c633f14)

Chapter Six (#uecd43dc7-5e82-5188-90ba-67ecf7883574)

Chapter Seven (#u8a84b2f9-5ac6-5c50-9000-941d09dc775d)

Chapter Eight (#ue75fb0b6-d52e-5ed4-b420-0fc1576027de)

Chapter Nine (#ueefb6843-5a25-5e02-8209-5032b32cf44f)

Chapter Ten (#uae1407b2-0996-51a0-b871-085c0f4e9d3b)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Annie Groves (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PART ONE (#u7a8e88bb-c8ea-5f18-be1a-76cec90b962c)

CHAPTER ONE (#u7a8e88bb-c8ea-5f18-be1a-76cec90b962c)

Spring 1941

Kitty Callaghan drew her coat more tightly around her and wondered if she’d done the right thing.

It was an old coat, but then nobody could get anything new nowadays. She’d never had much new to begin with, so at least everyone was in the same boat, now that war had been raging for over eighteen months. The material was worn and bobbled where her bag usually rubbed against it. It wasn’t much protection against the cold or the biting winds that blew in off the Atlantic. Well, she told herself, that wouldn’t matter now. She would soon be far away from Liverpool and everything she was familiar with, all she had ever known for every one of her twenty-two years.

She caught sight of herself in the dirt-smeared train window. A pair of dark eyes stared back at her, set beneath waves of dark hair, which she had tried to control with a few precious grips. Her face was white. That would be the light making her look like that. It was nothing to do with the fact that she was full of trepidation at what she had done.

Kitty had been lucky to get a corner seat. She knew that it was going to be a long journey – nobody could say quite how long, as the tracks were always getting damaged and then the race would be on to repair them. Her fellow passengers were in every sort of uniform. Soon she would be in uniform too.

Her decision to join the WRNS – the Women’s Royal Naval Service, known as the Wrens – had been a sudden one, and had come about partly thanks to a chance encounter at the New Year dance at the Town Hall. Kitty had been doing her bit for the war effort already, managing the local Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes (or NAAFI) canteen on the dock road near her home in Bootle to the north of the city. At first she had enjoyed it, finding it a challenge, and was satisfied that she was helping out, even if in a small way. But, having seen the devastation caused by the bombs dropped on the docks and all around, she knew she needed to do more. Her home city had suffered terribly from attacks by the German air force, the Luftwaffe. Family and friends had been hurt, and forced to make heartbreaking decisions, such as whether to evacuate their children away from the most dangerous areas. Yet everyone had been buoyed by the bravery of the pilots in the Battle of Britain back in the summer and, once it became clear that the war was not going to be over any time soon, people had begun to dig deep and find reserves of courage. So when Kitty had bumped into a recruitment officer at the dance, she had decided to pursue the enthusiastic young woman’s suggestion that she consider joining up.

‘Penny for ’em!’ One of the young lads, in an army greatcoat that was far too big for him, leaned across from the seat opposite and grinned at her. ‘What are you doing, then? Going to see your boyfriend?’

Kitty was no stranger to dealing with such comments – you couldn’t afford to be standoffish in the NAAFI canteen. She had learned to give as good as she got. Fortunately, having three brothers at home, she had already had plenty of practice. But she also knew not to indulge in idle conversation when she couldn’t be certain who might be listening, so she shook her head gently. ‘Careless talk costs lives,’ she said lightly.

The young man’s face fell. ‘Go on, a pretty girl like you must have a boyfriend,’ he persisted. He looked about seventeen with his baby face without a trace of stubble.

‘Don’t pester the lady – she’s right,’ said one of his companions, whose own uniform showed he was a corporal, not just a private. ‘You don’t know if there’s spies out there in the corridor or not. Sorry, miss, he don’t mean nothing by it. No offence, like.’

‘None taken,’ said Kitty. She was going to have to spend many hours with these people and there was no sense in making a scene. Equally, though, she didn’t want them larking about and chatting her up. She had some serious thinking to do.

Her own big brother had signed up almost as soon as war broke out. Jack was a pilot with the Fleet Air Arm and had already had a narrow escape when his ship went down after being attacked by the enemy. He’d been wounded by a bullet in the shoulder, but insisted he was better, and had returned to active service as quickly as they’d let him.

Danny, the brother who was just over a year younger than her, was in a reserved occupation on the docks, although at the moment he was recovering from an accident. It had nearly killed him, and could have taken scores of others with him. Kitty shut her eyes briefly at the memory. Danny had been the hero of the moment, taking the place of a fire-fighter who’d collapsed when trying to save a burning cargo ship. What Danny hadn’t told anyone was that he’d been turned down by every one of the Forces because he had an enlarged heart, the result of rheumatic fever as a child. So when he himself collapsed soon after the exertion, Kitty and the rest of the family had had to cope with the shock of the accident and the additional news that Danny had a serious condition that would restrict him for the rest of his life. She shook her head a little. It was no good worrying. Danny was old enough to look after himself; and besides, he could talk his way out of just about anything.

As for Tommy … Kitty couldn’t contain a sigh at the thought of her youngest brother, just eleven years old. As their mother had died giving birth to him, and their father while alive had been a feckless drunkard, she had raised him almost as her own. He’d also had a rough time of it over the past year and a half since the war had broken out, but he’d finally agreed to be evacuated. Kitty had no concerns on that score; he’d gone to a farm in Lancashire where their neighbour Rita’s children had been made more than welcome. He would be fussed over and pampered by the farmers Joan and Seth, safe from the attentions of the Luftwaffe that had made life in Empire Street so perilous. While she knew in her heart of hearts he had wanted to stay at home for the excitement of collecting shrapnel and being in the thick of things, it was for the best. Little Michael and Megan from across the road were there to play with, and he’d be better fed than the rest of the family put together.

So why was she so full of doubt? Kitty mentally gave herself a shake. She should be grateful. She’d survived the bombings where so many hadn’t. She’d been lucky to meet the kindest man in the midst of all the chaos at Linacre Lane hospital, where Danny and Tommy had been treated. Dr Elliott Fitzgerald was so far above her in social station that she sometimes had to pinch herself that he’d even talked to her, let alone taken her to a posh dance at the Town Hall and seen her whenever his rare time off from the wards coincided with her being off shift from the canteen. He’d been immediately encouraging about her joining the Wrens. Plenty of men would want the woman with whom they were developing a relationship to stay close at hand, but not Elliott. He believed she could do it, and be a success. He’d held her hand, looked into her face with his beautiful blue eyes, and said that she would be wonderful and exactly what the country needed. Just having him next to her made her feel more confident, more assured.

So why wasn’t that enough?

Because, said a little voice in her head, he isn’t Frank Feeny.

Suddenly the train jolted to a halt. Shaken, Kitty peered out of the window, but of course all the signs at the station they’d just drawn into had been removed, for security. She’d never been this far from home before and didn’t recognise anything.

‘It’s Crewe,’ said the baby-faced private, but the corporal dug him in the ribs.

‘Shut up, Parker. You know you’re not meant to say that.’

‘Only trying to be helpful,’ said Parker, rubbing his side. ‘That hurt, that did.’

‘I’ll give you more than that to complain about if you don’t watch your mouth,’ warned the corporal.

Just when Kitty thought it could be getting nasty, the door to the compartment opened and a young woman stuck her head through the gap. ‘I say, could you shove up? Thanks ever so.’ Without waiting for a reply she swung herself in and hoisted a very elegant case on to the overhead rack. Kitty only had sight of it for a moment, but that was all it took for her to recognise its quality, so very unlike her own shabby one beside it.

‘I’m so glad to have a seat,’ the woman went on, giving the occupants of the carriage a dazzling smile. ‘I simply dreaded standing all the way to London. Now let me make amends for disturbing you by offering you some gingerbread. Mummy asked Cook to bake extra for this very reason.’

The soldiers immediately broke off from their quarrel and looked brighter. Kitty masked a grin. Maybe this journey wouldn’t be so bad after all. It was a sign, she told herself. Push all thoughts of Frank Feeny firmly away – he thought of her as a pesky little sister, that was all. She was better off in so many ways now that Elliott had come into her life. And, while she was nervous about what the coming weeks of training would bring, there was something else too. Excitement. Ambition. This was the start of something completely new, and she owed it to her family, her friends, but most of all herself, to make the very best of it.

CHAPTER TWO (#u7a8e88bb-c8ea-5f18-be1a-76cec90b962c)

‘So why aren’t you out helping Mam down the WVS?’ Rita Kennedy, née Feeny, demanded of her younger sister Nancy. They were in the kitchen of the family home, even though neither of them lived there any more since their marriages. Then again, both marriages had turned out very differently to how they’d expected, and they both preferred the comfort of their mother’s warm and welcoming kitchen to just about anywhere else on earth.

Nancy planted her elbows firmly on the old chenille tablecloth and sipped from her cup of tea. ‘Because I’m minding Georgie. He’s still having a rotten time with his teething. The last thing they’ll want is a howling baby shouting the place down.’

Rita raised her eyebrows, knowing full well that Nancy would do anything to get out of hard graft. While their mother was a mainstay of the Women’s Voluntary Service, as well as organising salvage collections, cookery classes, make-do-and-mend classes and being the auxiliary fire warden for Empire Street, Nancy rarely lifted a finger if she could help it. She was perfectly happy to let somebody else mind her young son – usually their sister-in-law Violet, who, having no children of her own yet, liked nothing better than entertaining young George, who was not quite a year old. That suited Nancy down to the ground. Now she pouted at her big sister – a look she’d practised for many a year.

‘You needn’t be like that about it.’

‘I didn’t say a thing,’ Rita pointed out, pulling out a wooden chair and sinking gratefully on to it. She’d been on her feet all day.

‘You didn’t have to,’ Nancy complained. ‘Your sour look gave it away. Someone’s got to look after Georgie, and now Violet’s thrown herself into the WVS as well, it’ll have to be me.’

‘What about Sid’s mam?’ Rita asked innocently, waiting for the firestorm that would follow. She wasn’t disappointed.

‘That old witch! I wouldn’t trust her with a baby.’ Nancy was incensed. ‘It’s bad enough having to live under her roof – we don’t want to spend any more time with her than we have to. I don’t know how she does it, but she manages to be a proper busybody and a big streak of misery at the same time. I mean, Sid’s been a POW since Dunkirk, but every day she goes on and on about it like it’s only just happened. It’s as if nobody else has lost anyone in this blessed war. It’s all about her, what a martyr she is, how it’s destroying her health. It’s enough to get your goat.’

Rita couldn’t argue with that; Mrs Kerrigan always had been one of their nosiest neighbours, and she’d taken to the role of grieving mother as if she’d been born for it. Rita smiled to herself. Whatever disapproval anybody had for Nancy’s ways was like water off a duck’s back; she didn’t seem to give a hoot about other people’s opinions. Still, her sister could be remarkably callous about her missing husband, and Rita knew she was sailing a bit close to the wind these days. ‘You’re going to have to keep on the right side of her, though, for when Sid gets back,’ she said. ‘He’ll have been through enough without coming home to find his wife and mother at daggers drawn.’

‘Oh, I don’t want to dwell on it.’ Nancy tossed her head, making her red hair swing about her shoulders. ‘We none of us know when he’ll be back. It’s too depressing to think about.’

More like Nancy didn’t want Sid back to cramp her style, Rita thought, but decided to keep her thoughts to herself. It couldn’t be easy for Nancy, rattling round in that gloomy big house with a mother-in-law who made no secret of disliking her. As for Mr Kerrigan, nobody ever saw him. He worked nights on the Liverpool Post and kept totally different hours to the rest of his family, which Nancy figured was to stay out of the way of his disagreeable wife. Nancy spent as much of her time as she could in her mother’s house, and had even come back to live there for a while, before Violet had arrived and it had simply become too crowded to contain them all. Reluctantly she’d taken little George back to his other granny.

Rita sighed. She was hardly so squeaky clean herself. She pushed thoughts of the circumstances of her marriage to her husband Charlie out of her mind, feeling too exhausted to think about it now. She loved her work as a nurse, but ever since the local infirmary had been bomb-damaged, she had been working at the hospital on Linacre Lane, a much longer walk away. She didn’t mind the walk itself – especially now that the buses were so unreliable – but the journey there and back combined with long shifts and the weight of responsibility of being a nursing sister wore her out. She reached for the teapot before Nancy could help herself to a refill. Guiltily she realised she was drinking her mother’s tea ration, though Dolly Feeny wouldn’t have begrudged her eldest girl a cup. The whole family were proud of Rita, who’d kept at her post while the docks were bearing the brunt of the Luftwaffe’s devastating raids.

Warming her hands on the cup, Rita leant back. ‘That’s better.’ It was amazing what a drop of tea could do to restore your spirits. ‘Have you heard Mam’s latest?’

Nancy glanced up. ‘No, what?’

‘She’s gone and put her name down for a victory garden. She was talking about it at Christmas and I thought she’d given up the idea, but no. Now the days are getting longer it’ll soon be time to start planting seeds and I don’t know how she’ll manage.’

‘Well, I suppose we could all do with more fresh fruit and veg,’ said Nancy eagerly. Her mouth watered at the thought of strawberries in the summer. Even if there was no cream or sugar to go on them, they could always use evaporated milk.

Trust Nancy to jump straight to how she’d benefit herself, thought Rita. ‘Yes, that’s all very well,’ she persisted in trying to make her point, ‘but how will she find the time? Look at how much she’s doing already. She doesn’t get enough sleep as it is – not that there’s any telling her. We’re all going to have to muck in.’

‘You’ve got to be joking!’ Nancy cried hotly. ‘What, go grubbing round in the dirt? Lots of these gardens are just on dug-over plots where bombs have dropped, aren’t they? They’ll be filthy, not even like proper allotments. I’m not having anything to do with it. It’ll ruin my nails.’ She turned her hands to admire the latest shade of polish she’d managed to procure. It wasn’t easy to come by and she had no intention of spoiling her careful manicure by wielding a spade.

‘All the more for us, then.’ Rita drained her tea. Even though her sister was annoying, it was fun to wind her up and it was better than the alternative – going back to her own house and her own difficult mother-in-law. But there was no getting away from it. She rose to her aching feet, steeling herself for the short walk to the corner shop across the mouth of the alley. ‘I’ll see you tomorrow, Nancy.’

Nancy nodded absent-mindedly as her big sister made her way out of the door. Truth be told, she had more urgent matters to worry about than whether she’d be needed to take a turn on the new vegetable beds. She was sure she could get out of it – she could usually wheedle her way into her mother’s good books and persuade her somehow. There were some things, though, on which her mother wouldn’t budge.

One of those was how the wife of a POW should behave. Both her mother and her father had been very angry with Nancy when her other sister, young Sarah, had accidentally seen her canoodling with a man in a bus shelter back in December. Sarah had clearly been torn in her loyalties and very upset about the whole thing, but in the end had spoken up, more because if anyone else had seen them it would have been ten times worse.

As far as Dolly and Pop were concerned, that was the end of the matter. Nancy had been warned in no uncertain terms that she’d have to watch out for her reputation. It was bad enough to be a fast woman, but to be one when her husband had been taken prisoner in the course of serving his country was not to be contemplated. They had spelled out to her just what sort of reaction she could expect if she continued down that route.

Nancy shut her eyes and remembered. It hadn’t been just any man. It was Stan Hathaway, local boy made good. Even though his grandmother lived just around the corner from Empire Street and his family weren’t anything special, he’d managed to go to university and was now a flight lieutenant in the RAF. If anyone deserved a bit of fun on his precious home leave, it was him. Besides, he made her feel something that no other man had – not even Sid, back in the days when she’d first fallen for him, before she’d taken off the rose-tinted spectacles and realised what he was really like. But by then it had been too late and she’d been pregnant with Georgie. But Stan … he was utterly different. He was sophisticated and smart, and made her think she was those things too when she was with him. She could just imagine his arms around her, his persuasive whisper in her ear, the way her skin seemed to fizz with electricity at his touch.

She started suddenly as a wail came from the room next door. Georgie was awake again and it didn’t sound as if his nap had eased his teething troubles. Carefully she got up, making sure not to catch her precious nylons on the chair. She’d have to wait until Stan’s next leave to get new ones – he always seemed to know a way of finding them, and was only too pleased to give them to her. He used to joke that it was his excuse for finding out if they fitted her properly …

Guiltily she wondered if that tea had tasted right. Maybe she’d got another one of her upset stomachs. She’d had a few of those lately. That was all it was. She wouldn’t even think about the alternative.

Rita pushed open the back door to the living quarters, which were behind and above the corner shop. She paused to listen. In days gone by there would have been the constant buzz of gossip from the shop, as her mother-in-law Winnie Kennedy extracted the juiciest morsels of scandal from anyone and everyone, before selling on her carefully hoarded luxury items that only a select few customers knew about. Sometimes it was as if rationing had never happened. Being so near the docks, there were always folk who could get hold of just about anything for a small consideration, even though this was strictly illegal.

Now there was only silence. Rita groaned inwardly. Winnie had changed, and it wasn’t because of the destruction of so many homes around them or the loss of life that had shattered so many families around Liverpool in general and the docks in particular. In fact most people had become more defiant, nobody wanting to give in to the terror of the bombs. The people of Merseyside had come together and refused to be cowed. But Winnie had retreated into an angry shell.

She had always carried on as if she was a cut above everyone else, and had raised her son Charlie to feel the same. She’d never troubled to hide her resentment of Rita, who had never been good enough for her beloved son. Rita had married Charlie knowing all this only too well, but she’d had little alternative as she’d been pregnant with Michael. She and Jack Callaghan had been young sweethearts, but too young and naïve to realise what they were doing. When Jack had been sent away on his apprenticeship, Rita had panicked – making the worst decision of her life. Many a time over the past eight years she’d berated herself for the choice she’d made, but she had made her bed and now had to lie on it. The living quarters had been crowded when they’d all lived there, with Winnie’s bedroom right next to Charlie and hers, and even more so when baby Megan had arrived on the scene. Rita had treasured the dream of finding a place of their own, away from Charlie’s interfering, domineering mother, hoping that this would be the solution to the widening cracks in her marriage. She’d been foolish to think that, she now realised. Now she was wise to Charlie’s callous and vicious nature, but here she was, trapped with the poisonous Ma Kennedy, Charlie goodness knows where, and her children far away from Empire Street.

She sighed at the thought of her children; she ached at being apart from them. However, she knew Megan and Michael were safe, away from the air raids, living on a farm in Freshfield all the way out in Lancashire. Tommy Callaghan was with them, which would liven things up, and she tried to visit them when she could, always amazed at how they thrived away from the air raids. They looked so different from the pale children of the city who remained; those whose parents couldn’t bear to part with them and who now roamed the bombsites of Merseyside, exposed to many dangers. Thank God the farming couple had welcomed them with open arms, and Rita knew the children would have the love and security they needed – not to mention all those fresh vegetables and meat, and the cream of the milk and the rich golden butter they could never have hoped for in Empire Street.

She pushed open the inner door to the shop. Winnie was slumped behind the till, her eyes dead. ‘Oh, it’s you.’ She could barely summon the interest to speak.

‘Of course it’s me. I’m late because the shift didn’t finish on time.’ Rita thought it best not to say she’d stopped off for a cup of tea next door. ‘Shall I put the kettle on? It’s freezing in here.’ No wonder there were no customers, she thought.

‘Certainly not. Tea’s rationed, as you should know.’ There was a trace of the old Winnie, snobbish and sharp. The fact that she had a case of tea stowed away in the cellar was not to be mentioned. Rita bit back the retort.

‘If you’re sure? Then I’ll go and get changed.’ Rita let herself out of the shop again and made her way upstairs.

Winnie’s situation was all of her own making. She’d kept a secret for twenty years or more and it had only come to light during a terrifying raid just before Christmas. Dolly, as fire warden, had had to make sure everyone left their houses and went to the bomb shelter at the end of the street, but Winnie had resisted, even though the roof of the shop was alight. She’d been desperate to rescue a box of papers from the loft. Dolly, at great risk to herself, had managed to persuade her difficult neighbour to get to safety and had looked after the box. In all the confusion of the raid it had finished up in the Feeny family home. Both Dolly and Rita were now aware of its contents.

Far from relying on the income from the shop, it transpired that Winnie had been the owner of three properties: the shop and its living quarters, a large house in Southport and a guesthouse in Crosby. All those years Rita had dreamed of moving out – and Winnie had said nothing, like a dragon sitting on a pile of gold. She’d been far more keen on keeping Charlie tied to her apron strings, where she wanted him.

Charlie had had other ideas, and while his mother had boasted to all and sundry about his job in insurance, he’d used it to pay calls on well-heeled women on their own in the afternoons. Winnie had either turned a blind eye or refused to believe it was possible – just as she’d managed not to notice the marks on Rita when Charlie’s rage turned against his wife. Charlie had finally taken off to the house in Southport, supposedly so the children would be safer, which was managed by a very accommodating woman called Elsie. He’d even put it about that she was his wife. Rita had eventually tracked them down and taken the children away – just in time, as a stray bomb had ripped the front off the once-grand house, and the children had been left standing in the road.

Rita’s parting shot had been to hand Charlie his call-up papers. He was a coward, all bluster and smarm; the only fighting he was capable of was to hit a woman behind closed doors. She had no idea where he was now and she didn’t care. That was Elsie’s problem.

There had been one more document in Winnie’s box that if anything had been even more startling. It was a birth certificate for a child called Ruby, born to Winnie Kennedy, but two years after her husband had died. The father’s name was left blank. This baby would now be coming up to twenty-one years of age. And when Rita had tracked down Charlie and Elsie, the neighbours had been keen to point out that the couple were often in the pub of an evening – but the children were looked after by a young woman called Ruby.

So things had come to an uneasy standoff. The people of Empire Street were mostly a good lot, but prone to suspicion and gossip. Charlie’s disappearance, and the fact that he’d never been seen in uniform, was a gift to the likes of Vera Delaney, who would love to wipe the smug smile off Ma Kennedy’s face and take her down a peg or two. Only a few Feenys knew the full truth. Winnie was slowly going to pieces waiting for her big secret to be blown.

Rita, meanwhile, harboured a secret of her own. When she’d gone to rescue her children, she hadn’t done it alone. Jack had taken her: Jack Callaghan, Kitty’s big brother, her childhood sweetheart and – as she’d finally confirmed to him – Michael’s real father. She’d tried to be a good wife to Charlie, to forget everything that had passed between Jack and her; they’d been too young, and fate in its many forms had made it impossible for them to be together. Now he was back doing his duty, escorting naval convoys across the vital supply routes of the North Atlantic. How she missed him. How she wished they’d somehow found a way all those years ago to overcome all the obstacles – but that hadn’t happened. Now she had to face the fact that her feelings for him had never died, but that she could not have him. The fact that Charlie had broken every bond of duty to her as a husband was neither here nor there. Divorce wasn’t a word you’d ever hear in Empire Street; no matter what a husband had done to his wife, she’d be expected to stand by him. The best she could do was to write. Rita had promised that to Jack and she wouldn’t break her word. The letters were hurting no one, and if they kept his spirits up through those dark nights on the Atlantic, then that’s what she’d do, and to hell with the holier-than-thou attitude of the rest of the world – couldn’t they have those precious words to share, if nothing else? But now Kitty had left, she would have to find another way of receiving his letters to her. Next to the children she adored, the letters were the one chink of light in this miserable life she was stuck with.

A noise at the top of the stairs startled her. A slight figure with huge pale-blue eyes and a frizz of pale- blonde hair emerged, smiling nervously, almost like a frightened child.

Rita took a long look at her, and noted again how much she looked like Winnie, her mother. Not so much her hair, but her nose and her eyes were very similar, though the young woman’s had a gentleness to them which Winnie’s certainly didn’t. Something else for the gossips to get their teeth into … Rita forced herself to get a grip and spoke steadily and comfortingly. ‘Hello, Ruby, come and have a cup of tea, love.’

As Ruby tip-toed down the stairs towards her, Rita looked around her at the shabby, care-worn kitchen – she saw the loose tea that Winnie had tipped into the sink, the chipped cups on the drainer and the cold grate that had been left for her to make up herself. She sighed deeply – if she didn’t have Jack’s letters as a lifeline, then she didn’t know how she would keep on going.

CHAPTER THREE (#u7a8e88bb-c8ea-5f18-be1a-76cec90b962c)

‘Are you sure you don’t mind me taking the top bunk?’

Kitty shook her head. ‘No, I don’t like heights at the best of times. I’m much better off down here.’ She thumped the hard pillow into something she thought might be a more comfortable shape. It was never going to be soft, but at least all the bedding was clean. She’d heard horror stories about some service accommodation, and apparently the Land Army girls often had to put up with worse.

‘Bit of a coincidence that we ended up being billeted together, isn’t it?’ asked the elegant young woman from the train, whose name was Laura Fawcett. They’d introduced themselves on the journey, Kitty explaining she’d come from Liverpool, and learning in turn that Laura, although from Yorkshire, had spent lots of time in London and knew it well. ‘I’m glad we got the chance to get acquainted before the others turn up. Looks as if they’re expecting a lot of new recruits.’

Kitty had been taken aback on arrival in the capital and had been glad to have the much more confident Laura to guide her to their new home in North London. Although she was well used to the bustle of Liverpool city centre, this place was on a different scale. The sheer number of people was overwhelming, many of them in uniform of one sort or another, all weaving around each other at baffling speed. Kitty had gripped her new friend’s arm, totally disoriented. Laura had taken it in her stride, mildly annoyed to find that holes in the road meant she couldn’t take the route she’d originally planned, but swiftly deciding upon a new one. She’d plunged into the Underground and Kitty had followed immediately behind, terrified at the thought of getting separated. That had been her introduction to the Northern Line.

Now Kitty glanced uneasily around the large room they were in, full of bunk beds in readiness for the arrival of trainee Wrens. She was used to sharing a house with her brothers, and not having a minute to herself, but her bedroom, basic though it was, had always been her sanctuary. She’d done her best to soften it with her eiderdown and the few bits and pieces that remained of her mother’s possessions. Here there would be room only for the most functional items. She wondered what sort of bedroom Laura had had and what her home was like – nothing like Empire Street, she was sure of that.

Laura appeared to have no such doubts and finished packing away the small amount of clothing they were recommended to bring in no time, somehow managing to cram in some very elegant-looking frocks as well. ‘This place must have been a school, just look at it. Certainly wasn’t made to sleep in.’ She glanced around at the huge windows and high ceilings. ‘Bet it’ll be freezing. Oh well, maybe they’ll work us so hard we won’t care. Can’t be as cold as up north, that’s for sure. I’m used to the wind howling over the moors so I probably shan’t even notice. How about you?’

Kitty smiled, remembering the force of the westerly gales that came in over the Atlantic with such regularity. ‘Oh, that won’t worry me,’ she said lightly. ‘We have to put up with that all the time in Liverpool. At least they’ll give us uniforms to keep out the worst of it. I’ve been wearing dungarees for work in the NAAFI and this uniform is much nicer – warmer too.’

Laura held up the bluette overall she’d been issued with. ‘It’s a bit stiff, isn’t it? It’ll be itchy as anything.’

Kitty grinned, thinking that her pretty new friend probably wasn’t used to anything but the finest material, and would not have had to wear anything practical, certainly not like the often-patched clothes she’d had to put on for scrubbing down the NAAFI canteen after it closed every day. She smoothed down the blue-and- white bedspread on her narrow bunk, running her hands over the anchor motif. She couldn’t help wondering what her brother Jack would be doing, out there on his aircraft carrier, facing God knows what.

‘Let’s go and see where that canteen is that they told us about,’ Laura suggested, hanging up the overall once more. ‘I shan’t wear that until I have to. If this is going to be my last day in my own clothes for a while, then I’m going to make the most of it. Two weeks of basic training and then heaven knows what we’ll be in for or what we’ll have to wear.’ She shrugged into her pale-yellow cardigan, which Kitty was fairly sure was cashmere. It perfectly set off Laura’s mop of beautifully cut blonde curls.

They made their way to the lower floor and uncertainly down an echoing corridor, trying to remember what the officer who’d welcomed them had said. There were so many doors – but then the unmistakable smell of cocoa hit them and they followed their noses to what might once have been the school refectory. A woman in her forties was standing by a large urn. She wore a bright turban on her head and Kitty reflected that up until a short while ago this would have been her, greeting the servicemen and sometimes -women who’d come through the doors of her own canteen.

‘Hello, girls,’ the woman said, immediately friendly. Steam rose from the urn. ‘I can do you tea or cocoa. What’ll it be?’

‘Cocoa,’ Laura and Kitty said immediately. Kitty couldn’t remember the last time she’d had cocoa. Before the war, at home in Empire Street, there hadn’t always been enough to go round; it was ironic that rationing meant that some people were better fed now than before the war. Kitty’s mother had died when she’d been a young girl, and Dolly Feeny, their neighbour, had been the closest thing to a mother she’d had since. Kitty’s father had liked a drink – too much sometimes − often spending down the pub what was intended for the housekeeping. Thank God for her brother Jack, and for Dolly, who’d made sure that the Callaghan kids didn’t go without. The Callaghan and Feeny children had been as thick as thieves growing up. Eddy had been like a brother to her – and Frank, of course, though in the last few years, Kitty knew her feelings had changed into something deeper, something enduring. Kitty pushed thoughts of Frank Feeny from her mind again – he’d never see her as anything other than a little sister, and it was time to put away her childish dreams and look to the future. The smell of cocoa drifted tantalisingly up to her nose. This was a treat not to be missed.

Gratefully they warmed their hands on their cups as they made their way to a battered wooden table next to a window. Through it they could see a curving drive and, beyond that, down the hill, London was spread out beneath them. Kitty took a tentative sip to see how hot the drink was and smiled. ‘Delicious. Haven’t had that for a while.’

Laura smiled back ruefully. ‘Strange, isn’t it? How quickly one gets used to not having the everyday stuff.’ She took a sip too. ‘Heavenly. That’s made it worth joining up already.’

Kitty eyed her new companion curiously. She seemed to be about the same age as her. ‘Why did you? Join up, I mean?’

Laura paused. ‘Well, I suppose it’s a case of doing my bit. And I was tired of sitting at home, doing nothing.’

‘Did you really do nothing?’ asked Kitty. Even though she hadn’t known this young woman long, it didn’t seem very likely.

Laura snorted. ‘Oh, nothing much. I knitted for the troops and went to some WVS meetings with my mother, but that’s not really a lot of help, is it, when we’re facing a fight to save our country? I knew I could do more. Well, I hope so anyway. I don’t know what they’ll decide I’m best at, but I look forward to finding out.’ She took another sip. ‘What about you?’

Kitty gazed out at the trees coming into bud, swaying in the breeze. ‘I think it was seeing what my brothers were doing and realising I didn’t have to look after them any more. Jack’s with the Fleet Air Arm, Danny’s on the docks, though he’s off sick at the moment, and Tommy’s been evacuated. I’ve run around looking after them for years and now they don’t need me so much, I wanted to do something more – something that will make a difference.’ She met the other woman’s gaze. ‘I don’t know what I’ll be best at either. I hope it isn’t cooking. I’ve done that and I’ve loved it but I want to try something different. I’ve never left home before. Even though we’re at war, I can’t wait to see a bit of London. D’you think we’ll have time?’

‘We’ll make time!’ Laura declared. She raised her cup and chinked it against Kitty’s. ‘I know exactly what you mean about doing more … Here’s to having fun, and damn the war. Those Germans aren’t going to put a stop to me showing you the delights of our capital city. Freddy used to show me around every chance he got.’ She stopped suddenly.

‘Who’s Freddy?’ Kitty asked shyly, hating to be nosey but keen to get to know this force of nature. Being around Laura was exciting in itself; she made it seem like anything was possible. ‘Was he your chap?’

‘No, nothing like that.’ Laura’s voice caught but then she cleared her throat. ‘No, he was my brother. Is my brother. He’s missing in action, has been since November. He’s a pilot.’ She looked away quickly to the faint outlines of the buildings on the horizon. ‘He was only a year older than me, we did everything together – or at least we did until he was sent away to school and I had to stay at home and not bother my silly little head about serious subjects like maths and things like that. Still, we went everywhere together when he was home. He even taught me to drive.’

Kitty felt a bit awkward. She’d only known this woman a few hours, but they were going to be sharing a room and intimacy couldn’t be avoided. She desperately wanted to be a part of this new life and being shy wasn’t going to get her anywhere. She reached out her hand and took Laura’s shaking palm in her own. ‘Look, I realise it’s easy to say, but you mustn’t give up hope. I know. It happened to my brother Jack; his ship went down and we didn’t know where he was or what had happened to him. It was awful. It felt like a lifetime, but in the end we got news that he was alive and on the way home. He was shot but he says he’s better now and he’s back in active service. Don’t ever give up hope; it’s what keeps us going.’

‘Thanks.’ Laura seemed to give herself a mental shake and then smiled with determination. ‘Nothing I can do about it. Sitting around moping won’t help and Freddy wouldn’t stand for it, so I must buck up. Mummy’s furious with me for putting myself in danger but I told her not to be silly. They won’t actually let us fight, so I might as well go and make myself useful in whatever way I can. And if one of those ways is showing you around London, then all the better. Anyway, what about you – do you have a chap? With your looks you’re bound to have, hope you don’t mind me saying.’

Kitty furiously tried to stop herself from blushing. She’d got used to being called all sorts of things when behind the counter at the NAAFI, and fielding outrageously flirtatious remarks from many of the service-men, but to have her appearance commented on by this smart and very attractive young woman was an-other thing entirely. ‘Sort of,’ she admitted. ‘Well, nothing formal or anything, but I was walking out with a lovely man called Elliott.’ She could hardly believe she was going to say the next words. ‘He’s a doctor. He looked after my little brother Tommy when he was ill once.’

‘Oh, well done you!’ Laura beamed. ‘A doctor – that’s jolly nice. Oh God, I sound like Mummy. But you know what I mean. Doesn’t he mind you going away? Did he beg you to stay at his side?’

‘No, the very opposite. He said if it was what I wanted, I should leap at the chance,’ said Kitty, aware now that pride had crept into her voice. She knew she was lucky to have such support from him. ‘Also, he’s from London, so he wants to come and see me when he next has some leave.’ Her face fell as she remembered his workload. ‘That doesn’t happen very often though. And even when he thinks he’ll have time off, he’s often called back to the ward for an emergency. We really have been through a lot over the past few months. The bombing felt non-stop over Christmas.’

‘Oh, I know.’ Laura’s face was instantly sympathetic. ‘Even though they never give the name of the city on the radio, just say it’s in the northwest or wherever; we only heard about it afterwards, though word sort of gets around, doesn’t it?’

Kitty nodded sadly. ‘Should we even be talking about it now?’ She glanced around nervously. There was hardly anybody else in the room, as so many of the new recruits wouldn’t arrive until tomorrow, but all the same she was aware that the least said the better.

‘Well, it’s over and done with,’ said Laura pragmatically. ‘I don’t suppose it can do much more harm. But anyway, that’s wonderful that your chap might be down to visit. Maybe he can show us some places I don’t know about.’ Her eyes brightened. ‘He can take us out on the town. D’you think he’d like that?’

‘I’m sure he would. He’s very kind – and he’s a very good dancer.’ Kitty smiled but felt an odd prickling of something else – not pride, not anxiety but … could it be jealousy? Wouldn’t Elliott be far better off with a girl from his own background, someone exactly like Laura? No, she mustn’t think like that. Elliott had been surrounded by gorgeous young nurses from every walk of life and yet he had chosen her. She had nothing to worry about. And, furthermore, if she was prepared to feel jealous, then that must mean she was over Frank Feeny, mustn’t it? But, as she settled herself into the unfamiliar bed that night, it wasn’t just the strangeness and excitement of her new surroundings that gave her a fitful sleep, but the blue of Frank Feeny’s eyes that seemed to invade her dreams.

CHAPTER FOUR (#u7a8e88bb-c8ea-5f18-be1a-76cec90b962c)

Rita stared at herself in the mirror in the bedroom she used to share with Charlie and thought how much weight she’d lost. It was no wonder: rushed off her feet all day, walking to and from work as often as not, serving in the shop when she wasn’t on duty, and all on less food than she was accustomed to. By the dim light of the overhead bulb she could see her clothes were beginning to hang loosely on her, but she couldn’t exactly go out and buy a whole new wardrobe in a smaller size. She had once been proud of her curvy figure, and Jack had loved it … now there wouldn’t be much left for him to catch hold of. That was if he ever came back. And anyway, she wasn’t going to go down that route again; there was no future in it but heartbreak. So really it didn’t matter what shape she was, as long as she could keep body and soul together. Shivering, she knew it meant that she felt the cold more keenly. Still, it was March now and the weather would soon turn warmer.

There was a gentle knock at the flimsy door. Rita started. It wouldn’t be Winnie, that was for sure. She would just barge in – or at least the old Winnie would have. Now she no longer bothered, which was a relief. ‘Come in,’ Rita called.

Ruby stepped into the room, as cautiously as a mouse peeping out of its hole to see if the cat had gone. ‘Rita? Um … can I come in?’

Rita wondered what this was about – Ruby usually kept herself to herself, and in fact she felt she knew the younger woman no better than when they’d first met, three months back. Even though they shared the same house, they barely saw one another, as Ruby kept to her attic room and Rita rarely had time to sit around downstairs. She sat down on the bed and patted the space beside her. ‘Come on in, Ruby. Make yourself comfortable.’

Shyly the young woman stepped forward and then sat where she’d been asked to, all without looking directly at Rita. Even though she was nearly twenty-one, she acted like a child, a timid one at that. Rita didn’t know if it was because there was something wrong with her, or because of how she’d been treated all her life. Being raised by that hard-faced Elsie Lowe would have been no picnic.

‘What’s wrong, Ruby?’ Rita could tell something was bothering her, and her naturally warm heart went out to her. ‘Take your time.’

Ruby jerked her head away and muttered something before she managed to say, ‘I’ve not done nothing wrong.’ She turned to face Rita and her huge blue eyes glittered with unshed tears. ‘Honest, I haven’t.’ She began to shake violently.

‘Ruby, of course you haven’t. Who said you did? Why are you saying this?’ Rita asked gently, wondering what could have frightened her. Everyone had been living with frayed nerves during the bombings, but those had tailed off recently. Was it the fear of the planes returning that had upset the young woman so much? ‘Don’t be scared, you can tell me.’

Ruby took a deep breath. ‘The police came.’ She looked away again. ‘I haven’t done nothing, really I haven’t.’

‘Police?’ Rita’s hand flew to her heart, immediately wondering if anything had happened to her children. Then she reasoned that they would have come to the hospital to tell her if it had been that. ‘Did they say what it was about?’

Ruby gave a big gulp. ‘I … don’t know. I heard them. They had loud voices. Mrs Kennedy shouted at them. They were very angry. I could tell but I didn’t go down. Then Mrs Kennedy went away with them.’

Mrs Kennedy! Rita had to stop herself from exclaiming out loud. Winnie was this poor girl’s mother and yet she wouldn’t even allow her to call her by her first name, insisting on the full and more formal Mrs Kennedy. And surely she hadn’t just shut the shop in the middle of the day? Even though she was a shadow of her former self, she still had an eye for profit.

‘You don’t need to worry, Ruby,’ Rita said, thinking fast. ‘It will have nothing to do with you. Otherwise they would have asked to speak to you, wouldn’t they? You haven’t done anything bad. They will have wanted to speak to Winnie. Maybe one of the customers has caused trouble, something like that.’ But Rita didn’t believe that for one minute. If it wasn’t the children, then there was only one person who was likely to bring trouble to this place.

‘So they don’t want to take me away?’ Ruby gasped. ‘They aren’t going to put me in prison?’

‘Of course not. Why would they do that?’ Rita tried to keep her voice reassuring, but she wondered just what Winnie had been saying to the poor girl while she was out of the house. Winnie loved to have control over people and here was a sitting target for her malice, daughter or no daughter. There was no telling how deep her spite ran.

Ruby’s face had just begun to brighten when the all-too-familiar air-raid siren began to wail. ‘Oh no, not again,’ Rita exclaimed without thinking. Then she said, ‘Don’t panic, Ruby, just go and get your bag – you do have it ready just in case, don’t you? – and then meet me downstairs. We’ll go to the shelter at the end of the road. I’ll see what we can take to eat, to keep our spirits up.’ Wearily she began to shrug into the coat she’d not long taken off. Eight thirty in the evening and she hadn’t had a proper meal all day.

Down in the kitchen she put her hand to the kettle and found it was still hot, so she quickly set about making a flask of tea. She knew Winnie kept packets of biscuits where she thought nobody could find them, and hastily bent to put a couple into her bag. A shadow fell across her as she stood up.

‘And what do you think you’re doing?’ Winnie spat.

‘Getting ready to go to the shelter,’ Rita said shortly. She didn’t intend to waste time or energy on her mother-in-law. ‘You’d better grab your things and come with us.’

‘Go to that shelter again? I’ll do no such thing,’ Winnie protested. ‘You get all sorts in there, all squashed in together – it’s not hygienic. You don’t know where they’ve been.’ She caught sight of Ruby hovering in the doorway. ‘My point exactly. I’m not going anywhere where I’ll be seen with her, for a start.’ Her eyes gleamed. ‘I’ll be safe enough in the cellar.’

‘In that case I’ll take that pie for Ruby and me,’ said Rita, catching sight of a pastry crust under a dome of white netting. ‘We all know you’ve got enough to feed an army stocked away down there.’

‘That’s my pie …’ Winnie began to protest, but Rita was too quick for her.

‘That’s my supper. I only just got back from my shift and I opened up the shop first thing this morning, if you remember.’ Rita wrapped the pie in a clean tea towel and added it to her bag. She was about to head out of the door when she paused. ‘Winnie, what were the police doing here? Weren’t you going to tell me?’

Winnie’s head snapped round. ‘Oh, someone’s been gossiping, have they?’

Rita thought that was a bit rich, coming from the vicious-tongued old woman. ‘Just explain to me what happened.’

‘It’s you who’s to blame,’ Winnie hissed. ‘Going round saying things about my Charles that aren’t true. It’s all a mistake. They won’t be back here again to bother me. Not unless you start telling your pack of lies again.’

‘What are you saying?’ Rita was momentarily shocked into silence. Then the penny dropped. ‘I see, they’ve come about him being a deserter, haven’t they? His papers arrived in December and I bet he hasn’t shown up to enlist, so they’ve come for him at last.’

‘He’s in a reserved occupation,’ Winnie insisted, with whatever misplaced dignity she could muster. ‘He would never stoop so low as to desert.’

‘Winnie, this is Charlie’s wife you’re talking to, not one of the customers you’re trying to impress,’ Rita sighed in exasperation. She finished fastening her bag. ‘Since when is being an insurance salesman a reserved occupation? And he didn’t even do much of that.’ She buttoned her coat. ‘And he’s already well practised at deserting – he left me quickly enough for his fancy woman, don’t you remember? Why don’t you tell that to your customers – the ones we have left, anyway. Listen, Ruby and I don’t have time for this, we have to go. Stay in the cellar if you have to … and,’ she added in an uncharacteristic moment of sharpness, ‘do look after that precious box of documents, won’t you? You wouldn’t want them to fall into the wrong hands.’ Leaving Winnie open-mouthed, she hastily took Ruby by the arm and ushered her through the side door and on to the pavement.

Empire Street was lit by a beautiful full moon, but Rita didn’t have time to stop to admire the bright silver light. She knew it would make the bombers’ task easier – although the anti-aircraft gunners would have a better chance of hitting a well-illuminated plane. People were pouring out from every door of the short street, hastening to the communal shelter. There was Violet from her parents’ house, her gawky frame easily recognisable. She waved and came over.

‘You on your own?’ Rita asked her sister-in-law in surprise. The Feenys’ place was usually bursting at the seams.

‘I am,’ said Violet in her strong Mancunian accent. ‘Dolly’s out fire-watching, Pop is on ARP duty, Sarah’s at the Voluntary Aid Detachment post down the docks and Nancy went back to her mother-in-law’s after supper, taking baby George with her. I’ve just locked up, so it’s as safe as I can get it.’ She smiled ruefully.

‘No sign of Frank?’ Rita asked.

‘No, he’s at his digs. He’s doing a lot of night shifts this week,’ Violet said. ‘Hurry up, I don’t like being out in this, it’s like daylight.’

As the alarm continued to wail, the three women broke into a run towards the shelter. Once safely installed alongside their neighbours, they unpacked their provisions and settled down, knowing it could be a long night. Rita was full of admiration for Violet; she never seemed to tire and her spirits never seemed to flag. She led them all in a singsong, though Rita thought the notes of ‘Run Rabbit Run’ and ‘Pack Up Your Troubles’ sounded rather gloomy as they fought with the rumble from the guns and incendiaries outside. And none of it could hide the whispers and mutterings occasionally directed at Ruby from some of the ruder elements among the street’s residents. Rita pulled Ruby closer towards her and made soothing noises to calm the strange girl as they waited, for what seemed like an age, for the all-clear.

Warrant Officer Frank Feeny hurried down the concrete steps of Derby House, ready to show his ID for the second time since entering the building. Nowhere in the entire country was security taken more seriously than in this fortified bunker in the centre of Liverpool, which was now home to the command for the Western Approaches. It was no exaggeration to say that the fate of the war relied on what happened in these two storeys of underground offices, mess areas, and the vital map room, which served as the nerve centre for the Battle of the Atlantic.

He checked his watch as he handed over his pass. Just about on time – he hated to be late, as did everybody involved in this high-level operation. Even though today he would have had a valid excuse. Last night’s raids had caused damage to the city centre, with the General Post Office being hit and the telephone exchange being affected; emergency exchanges had been at work ever since to ensure there was no breakdown in communications, but it was still a major cause for concern. Derby House had its own direct telephone line to the War Cabinet down in London, as top-secret news had to pass between the two centres at all hours of the day and night.

Frank rubbed his eyes, berating himself for feeling tired. After all this time in service he should be used to the demanding shifts by now. Despite the loss of his leg, he was still young and fit, even if he’d never be a champion boxer again. He needed to keep alert and all his wits about him. There was no room for anyone to make a mistake, here of all places.

‘Good evening, Frank.’ One of the teleprinter operators looked up as he passed by and gave him a cheeky smile. ‘Manage to catch up on your beauty sleep today, did you?’ She raised one eyebrow, and if Frank hadn’t known better he’d have thought she was flirting with him.

‘Can’t you tell? I’m handsome enough already,’ he managed to say automatically as he headed for the next room along. She was quite pretty, he recognised, with her hair in its victory roll, just like his sister Nancy liked to style hers. But he didn’t have time to think about girls. They were a distraction and he couldn’t afford that. One small slip and the consequences could be fatal in this line of work.

He was glad he’d settled into service accommodation rather than move back in with his family. He told himself it was because they were full enough, now his brother Eddy’s wife Violet lived there while Eddy was back at sea with the Merchant Navy, and even his little sister Sarah was little no longer and serving her own shifts as a trainee nurse. They didn’t need him waking them up at all hours. He’d have loved the comfort of his mother’s cooking and the reassurance of his father’s hard-earned wisdom, much of it gathered from the last war, but that was an indulgence he couldn’t afford.

He didn’t want to think about the other reason he stayed away. He would have had to look across the road at that other front door and know that Kitty was not going to step through it. When he’d first learnt that he was going to be stationed back in Liverpool, his heart had soared, despite his best attempts at reasoning, at the prospect of being near her. Somehow over the past couple of years she’d gone from being almost another sister to the one woman who made his pulse race, whose face he looked for in every crowd. But then he’d lost his leg and he knew no woman in her right mind would look at him twice. He had his pride; he wouldn’t beg. And he absolutely would not hold her back. In his current state he would be a burden to any woman and he didn’t want that – least of all for Kitty. It would be unbearable. He knew she was friendly with a doctor now, someone who had his full complement of limbs in working order, and whose job was to save lives; he was a lucky man and Frank hoped he knew it. But he cursed to the heavens above that just as he had returned to his Merseyside home, longing to see her again, Kitty had enlisted and been posted to the other end of the country.

CHAPTER FIVE (#u7a8e88bb-c8ea-5f18-be1a-76cec90b962c)

Nancy heard the flap of the letterbox rattle against the door and rushed to see what the postman had brought. She made a point of being the first to do this as she didn’t trust her mother-in-law not to open her letters; for an old woman who complained she was ill all the time, Mrs Kerrigan was surprisingly quick off the mark. She had just managed to stuff the two envelopes bearing her name into her waistband and cover them with her cardigan when, sure enough, her mother-in-law emerged from the dining room.

‘What is it?’ she demanded. ‘Is there anything from my poor boy?’

‘Must have been the wind,’ said Nancy brightly. ‘There’s nothing there. We can’t expect Sid to write all the time, can we? He’ll have other things on his mind. Oh, that’s Georgie crying again, I’d better go.’ She almost ran through the parlour door, ignoring the venomous look Mrs Kerrigan shot at her.

The parlour was gloomy, but at least it was Nancy’s own space, which she rented from her in-laws in addition to the room she’d shared with Sid and insisted on keeping. She’d go mad without some privacy in the daytime. They had plenty of room, which was about the only good thing she could say for the cold, unwelcoming place. Now she drew a chair as close to the window as she could, to catch what meagre daylight managed to filter through the heavy net curtains.

Georgie looked up expectantly, crawling over and trying to pull himself up with the help of the chair leg. Nancy regarded him sadly. It was a shame that Sid would miss his son’s first steps – it wouldn’t be long now. Then George would be all over the place and she’d never have a moment’s peace. George had never known his father, and she had almost forgotten what he looked like herself. She glanced over at the picture on the mantle of them both on their wedding day. She smiled at the picture, admiring her own shapely figure and the way the fashionable dress hugged her curves. It suited her to ignore the memory of the swell of Georgie in her tummy and how it had taken several goes to zip up the dress, and the bitter tears she’d cried that morning over the revelation that Sid had been carrying on with a fancy woman in the run-up to their big day – if she hadn’t been in the family way then they’d never have made it up the aisle. Her smile drained away. Sid, well, he just looked like Sid, didn’t he. ‘Good boy,’ she said wearily. ‘Mummy’s just going to read her letters, then she’ll play with you.’

She opened the first envelope with its familiar handwriting. Mrs Kerrigan must never see this, must never know that Stan Hathaway was still writing to Nancy. The pilot’s looping script was instantly recognisable and it would be evident to anyone who saw it that the letter came from someone in the services – not something from a POW camp forwarded by the Red Cross. She hoped the postman could be relied on for his discretion, but she was far from sure he could. Her heart was hammering as she tore open the flap, careful not to rip the flimsy paper inside.

It was a short note, as Stan claimed he didn’t have much time. Still, he wanted her to know he was thinking of her – Nancy could just imagine the gleam in his eye as he wrote that and exactly what he was thinking of – and couldn’t wait to see her again. He wasn’t able to say exactly where he was, but he was being kept busy, defending the skies. He wasn’t sure when his next leave would be but maybe in another six weeks or so, if he was lucky. Nancy sighed with longing. She remembered how his touch made her feel, the sheer delight of being held by him making her reckless. Six weeks seemed like for ever. She didn’t know how she’d be able to sneak past the dragon-like figure of her mother-in-law but she’d manage somehow. She’d have to. Nothing could keep her from the warm embrace of the gorgeous Stan Hathaway. Carefully she folded the precious piece of paper and reached to tuck it in her skirt pocket. She’d hide it away in her bedroom later. Mrs Kerrigan would think nothing of coming into the parlour if she was out and snooping about to see what evidence of her daughter-in-law’s flightiness she could uncover.

‘Mmm-mmm-mm.’ Georgie reached for his mother’s pocket, keen to see what the fuss was about.

‘No, that’s not for you,’ Nancy said shortly. Then she saw her son’s face fall and the trembling of his chin that heralded another bout of wailing. Hurriedly she relented, bending down and scooping him up to place him on her lap. ‘Look what Mummy’s got. This is a letter from Aunty Gloria. Shall we see what it says?’

She opened the envelope with the huge handwriting on it and George snatched it from her, happily tearing it in two and stuffing one bit into his mouth. Nancy debated whether to take it from him, knowing that even used envelopes should be saved as paper was so scarce. Then again, it was keeping him quiet, and as long as he didn’t actually swallow it, it would probably do him no harm.

She unfolded the letter from her best friend, written on lavender-coloured notepaper and bearing a faint trace of Gloria’s favourite perfume. Even though there was a war on, she’d never gone short of it, as there had always been an eager queue of men willing to do anything to present her with a bottle or two, no matter how it had been come by. Nancy felt a twinge of jealousy. She knew she was pretty but Gloria Arden was something else, with her natural silver-blonde hair and her golden voice. She looked like a film star and carried herself like one, for all that her parents ran the Sailor’s Rest pub at the end of Empire Street. She had gone to London and been taken on by a leading impresario, who was arranging far more glamorous concerts for her than her old regular spot at Liverpool’s Adelphi Hotel.

Nancy skimmed the page and gasped. The concerts had been a roaring success, Gloria reported, and she’d been asked to do more and more. London just loved her. The impresario, Romeo Brown, was talking about getting her to make a record. In order to whet the nation’s appetite for that, he’d suggested a tour. She’d be heading up north, and a date had already been booked in Manchester. So she was going to persuade them to add a date in Liverpool. Then she would be able to stay for a while to see her family and, of course, her best friend.

Nancy was torn between the envy she always felt at Gloria’s success and anticipation of her visit, when she would be able to bask in her friend’s reflected glory. Life with Gloria was never dull, that was for certain. Trouble and adventure seemed to follow her around wherever she went. Nancy paused guiltily as she remembered that Gloria hadn’t had it easy these past few months, as her posh pilot boyfriend had died saving her, shielding her from a blast during an air raid. Giles had only just proposed and it should have been the happiest night of Gloria’s life, but tragedy had struck right at the moment of her triumph. So perhaps it was only to be expected that she would throw herself into her singing career.

‘Well, Georgie, things are going to liven up a bit at last,’ Nancy cooed to her son, as she retrieved the soggy paper from his mouth. ‘Let’s see what Granny Kerrigan says about that.’

And, she thought to herself, Gloria would know what to do about the other matter that was bothering Nancy. Not that there was really anything to worry about. But just in case it did turn out to be what she feared …

‘Winnie not well again?’ asked Vera Delaney, her lips pursed as she rubbed her finger along one of the shelves in the shop. ‘That’s a shame. Without her behind the counter this place is going to rack and ruin.’ Dramatically, she held up her fingertip, which bore a trace of dust. ‘Still, I suppose you’ve got more shelves to clean now there’s not so much stock.’

‘Well, there is a war on.’ Rita struggled to keep her welcoming smile in place. ‘What can I get you, Mrs Delaney?’

Vera hesitated. When Winnie was in charge she could get all manner of extras under the counter, but she was convinced nobody else knew about this, so she had no intention of asking Rita for any favours. She was all too aware Winnie distrusted her daughter-in-law. ‘I’ll just get my sugar ration,’ she said, pursing her thin lips.

‘Awful how it goes so fast, isn’t it?’ Rita said, trying to make conversation. She hated it when the atmosphere in the shop felt unfriendly.

Vera ignored her comment. ‘Still no sign of your husband, then?’

Rita looked up from the counter. ‘I’m sure Winnie told you, he went away to look after the children safely.’

Vera rolled her eyes. ‘Dodge conscription, more like.’ She reached for her sugar and handed over her coupon. ‘Don’t you try to lie to me, young lady. Word is out that your man is a deserter, plain and simple. I feel for Winnie, really I do, but when I think about what danger my Alfie is in down the docks it makes my blood boil.’

Rita didn’t reply as she took the coupon, even though there was plenty she could have said about Alfie Delaney. True, he had a job on the docks and was therefore in theory in the most dangerous place on Merseyside, but he spent most of his time appropriating goods for the black market, some of which found their way into Winnie’s cellar. He was far from the only dock worker helping himself to any extras that were available, but Alfie took it to a new height. When he wasn’t doing this he was usually skiving. Admittedly he had performed one heroic deed, saving Tommy Callaghan from a burning warehouse, but that had been months ago. Vera couldn’t resist mentioning this again.

‘And him pulling that young rascal from the flames, when he had no call to be there! Putting his own life at risk like that! That’s something we won’t find your husband doing, I’ll be bound.’

Rita smiled tightly, knowing that to say anything would be to give Vera even more ammunition. Somehow she had to ride out these snide remarks and hold her head high. She cursed Charlie for his cowardice. His reputation threatened to ruin her own, but she couldn’t let that show.

Vera drew closer. ‘Maybe you could let me know when Winnie will be back at work?’

Aha, thought Rita, that’s what she’s after – her usual parcel of ill-gotten luxuries. Before she could say anything, the shop door opened again and a gust of wind blew sharply down the narrow aisle.

‘Morning, Rita!’ Violet’s lanky frame appeared silhouetted against a rare burst of sunlight. ‘Hello, Mrs Delaney. Cold out, isn’t it? Brass monkeys, as my brothers would say.’ She threw her head back and gave her braying laugh – which took some getting used to – and her bright scarf slipped sideways on her poker-straight hair.

Vera shot her an infuriated glance. ‘Well, if you’d tell Winnie that I asked after her …’ She beat a hasty retreat. Violet beamed at her cheerfully.

‘Bye, Mrs D, sorry you couldn’t stop!’ she called as the door slammed shut. She turned back to Rita. ‘Horrible old bag, what did she want?’

Rita shook her head. ‘Her sugar ration. Or that’s what she said, anyway. Really she wanted to carp about Charlie and to find out when Winnie’s back in charge so she can get bits and bobs on the QT.’

‘Still no word from him then?’ asked Violet sympathetically. She had never met the man, but had heard all about him from the rest of the family. Nobody had a good word to say about him.

‘Not a dickie bird. He’s as good as vanished,’ Rita confirmed. She couldn’t bring herself to mention the shame of hearing about the visit from the police. ‘I can’t pretend I’m sorry, and the children never even ask about him. We’re better off without him. I just wish people wouldn’t tar me with the same brush.’

‘No, you mustn’t think like that,’ Violet said, immediately reassuring. ‘Everyone knows how hard you work. How are Michael and Megan? Have you heard from them recently?’

Rita’s expression changed at the thought of her beloved children. ‘Yes, they write all the time – well, Michael writes, and Megan mostly sends drawings. They love it down on the farm. Joan and Seth, that’s the couple who run the place, spoil them rotten. Now they’ve got Tommy as well, they’re made up. He’s big enough to help out with the animals. They’ll never want to come home.’ She shook her head. ‘I miss them of course. It’s like going around without one of my limbs. But knowing they’re safe and happy helps.’

‘Can’t you go and see them?’ Violet wanted to know. ‘You can’t be at that hospital every day, week in, week out.’

Rita bit her lip. ‘It’s just that bit too far to do on my own. You can’t rely on trains or buses and they’re rather out in the sticks. Also, I get called in for extra shifts all the time – you know what it’s like. Every time there’s a direct hit on the docks or anywhere around here I could be needed and I hate to say no.’

‘Of course,’ Violet nodded. But she could sense her friend wanted to say more.

Rita glanced behind her, as if to check the inner door was firmly closed. ‘Besides, I’m needed here,’ she said quietly. ‘Winnie’s not been herself ever since I got the children back. She used to run this place like clockwork, but now she doesn’t seem to bother about anything – not the orders, or the cashing up, or filling the shelves. I have to try to keep on top of that as well as everything else.’ Her expression gave away just how tiring she was finding it.

‘Oh, I’m sorry to hear that, I hadn’t quite realised,’ Violet said. ‘You can’t do everything, you know. Maybe I could help? I’m not very organised but I can talk to the customers all right.’

Rita smiled in gratitude. ‘I know you could; you’d charm them and they’d love it. But you’re so busy already, what with helping with little George and the WVS, and aren’t you helping Mam with the new victory garden too? You’ve got your hands full.’

Violet shrugged. ‘That’s as may be, but you think about it. If I can be of any use I will – as long as you don’t expect me to do any sums. I never was any good at maths, just you ask my Eddy.’

‘Oh, I will, next time we see him.’ Rita cheered up at the mention of her brother, who everyone thought of as the quiet one in the family, but who had a wicked sense of humour. ‘Don’t let me keep you. Did you want anything?’

‘Some strong string,’ said Violet, reaching for her purse. ‘I’m going to mark out seed drills in the new plot. One of the old fellows from the Home Guard showed me how. We’ll all have fresh carrots and be able to see in the dark.’ She waved brightly and was on her way.

Rita grew solemn again as soon as she’d gone. Violet was a breath of fresh air, all right, but she’d feel bad asking her to help out any more than she already did. Besides, it was the sums that most needed attention. Rita had only just realised that the shop wasn’t making anything like the income it had before Christmas, and she had no idea what to do about it. They needed the money – now Charlie had given up any pretence of providing for them. But there was no time to think about it now. She checked her watch, knowing that she’d have to set off for the hospital any minute.

‘Winnie!’ she called through the inner door. ‘Are you ready to take over? I’ve got to get going.’

There was a shuffling and then Winnie slumped reluctantly along the corridor. ‘When are you going to give up that ridiculous nursing job?’ she demanded. ‘Your place is here, looking after the shop and me. Now you’ve driven Charles away, it’s the least you can do.’

Rita closed her eyes for a moment and prayed for strength. She would not rise to the vicious old woman’s bait. ‘I’ll see you later,’ she said instead, picking up her bag and jacket and making her way through the meagre stock to the outside door. She wrinkled her nose. It was still morning – but was that sherry she’d smelt on her mother-in-law’s breath?

CHAPTER SIX (#ulink_0158ae02-0b4c-5db1-918e-e5e50f47cb7d)

‘Blast!’ Laura sat back on her heels and groaned. ‘You must think I’m a waste of space, Kitty, but this is much harder work than I’d ever have imagined.’ She wrung the grey water out from her damp cloth over the galvanised bucket. The sleeves of her overall were dripping from where they’d come unrolled.