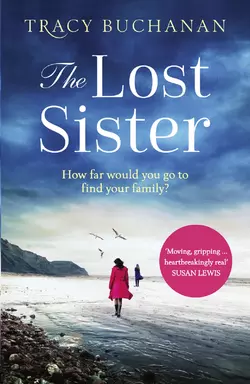

The Lost Sister: A gripping emotional page turner with a breathtaking twist

Tracy Buchanan

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 463.26 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ‘Refreshing and intriguing … I loved it!’ Tracy Rees, Richard and Judy bestselling author of The Hourglass‘Tracy Buchanan writes moving, gripping, heartbreakingly real family drama.’ Susan Lewis‘Twisty, emotional and far too hard to put down.’ Katie MarshFrom the #1 bestselling author of My Sister’s Secret and No Turning BackFor the first time in your life, she is going to tell you the truth…Then: A trip to the beach tore Becky’s world apart. It was the day her mother Selma met the mysterious man she went on to fall in love with, and leave her husband and child for.Now: It’s been a decade since they last spoke, but Selma has just weeks to live. And she has something important to tell Becky – a secret she been hiding for many years. She had another daughter.With the loss of her mother, Becky aches to find her sister. She knows she cannot move forward in her life without answers, but who can she really trust?An emotionally powerful novel full of twists and family secrets. Perfect for fans of Josephine Cox and Susan Lewis.