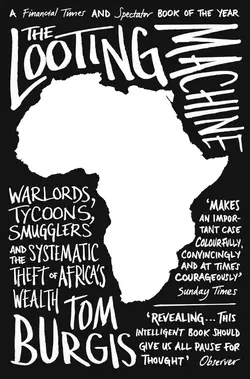

The Looting Machine: Warlords, Tycoons, Smugglers and the Systematic Theft of Africa’s Wealth

Tom Burgis

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 933.92 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Overseas Press Club Award Winner 2016A shocking investigative journey into the way the resource trade wreaks havoc on Africa, ‘The Looting Machine’ explores the dark underbelly of the global economy.Africa: the world’s poorest continent and, arguably, its richest. While accounting for just 2 percent of global GDP, it is home to 15 per cent of the planet’s crude oil, 40 per cent of its gold and 80 per cent of its platinum. A third of the earth’s mineral deposits lie beneath its soil. But far from being a salvation, this buried treasure has been a curse.‘The Looting Machine’ takes you on a gripping and shocking journey through anonymous boardrooms and glittering headquarters to expose a new form of financialized colonialism. Africa’s booming growth is driven by the voracious hunger for natural resources from rapidly emerging economics such as China. But in the shadows a network of traders, bankers and corporate raiders has sprung up to grease the palms of venal local political elites. What is happening in Africa’s resource states is systematic looting. In country after country across the continent, the resource industry is tearing at the very fabric of society. But, like its victims, the beneficiaries of this looting machine have names.For six years Tom Burgis has been on a mission to expose corruption and give voice to the millions of Africans who suffer the consequences of living under this curse. Combining deep reporting with an action-packed narrative, he travels to the heart of Africa’s resource states, meeting a warlord in Nigeria’s oil-soaked Niger Delta and crossing a warzone to reach a remote mineral mine in eastern Congo. The result is a blistering investigation that throws a completely fresh light on the workings of the global economy and will make you think twice about what goes into the mobile phone in your pocket and the tank of your car.