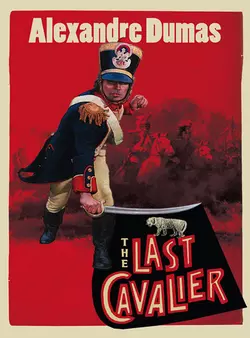

The Last Cavalier: Being the Adventures of Count Sainte-Hermine in the Age of Napoleon

Alexandre Dumas

The lost final novel by the master of the epic swashbuckling adventure stories: The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers.The last cavalier is Count de Sainte-Hermine, Hector, whose elder brothers and father have fought and died for the Royalist cause during the French Revolution. For three years Hector has been languishing in prison when, in 1804, on the eve of Napoleon's coronation as emperor of France he learns what is to be his due. Stripped of his title, denied the honour of his family name as well as the hand of the woman he loves, he is freed by Napoleon on the condition that he serves in the imperial forces. So it is in profound despair that Hector embarks on a succession of daring escapades as he courts death fearlessly. Yet again and again he wins glory - against brigands, bandits, the British, boa constrictors, sharks, tigers and crocodiles. At the Battle of Trafalgar it is his bullet that fells Nelson. But however far his adventures take him - from Burma's jungles to the wilds of Ireland - his destiny lies always with his father's enemy, Napoleon.

ALEXANDRE DUMAS

The Last Cavalier

Being the Adventures of COUNT SAINTE-HERMINE in the Age of Napoleon

Translated by LAUREN YODER

CONTENTS

Cover (#u46c2d404-c4a8-56a9-bb3f-227ae9ad0d1f)

Title Page (#u4b3d209a-e830-51b1-821e-e0ab3b5b2270)

PART I - BONAPARTE

I - Josephine’s Debts

II - How the Free City of Hamburg Paid Josephine’s Debts

III - The Companions of Jehu

IV - The Son of the Miller of La Guerche

V - The Mousetrap

VI - The Combat of the One Hundred

VII - Blues and Whites

VIII - The Meeting

IX - Two Companions at Arms

X - Two Young Women Put Their Heads Together

XI - Madame de Permon’s Ball

XII - The Queen’s Minuet

XIII - The Three Sainte-Hermines

XIV - Léon de Sainte-Hermine

XV - Charles de Sainte-Hermine [I]

XVI - Mademoiselle de Fargas

XVII - The Ceyzériat Caves

XVIII - Charles de Sainte-Hermine [2]

XIX - The End of Hector’s Story

XX - Fouché

XXI - In Which Fouché Works to Return to the Ministry of Police, Which He Has Not Yet Left

XXII - In Which Mademoiselle de Beauharnais Becomes the Wife of a King without a Throne and Mademoiselle de Sourdis the Widow of a Living Husband

XXIII - The Burning Brigades

XXIV - Counterorders

XXV - The Duc d’Enghien [I]

XXVI - In the Vernon Forest

XXVII - The Bomb

XXVIII - The Real Perpetrators

XXIX - King Louis of Parma

XXX - Jupiter on Mount Olympus

XXXI - War

XXXII - Citizen Régnier’s Police and Citizen Fouché’s Police

XXXIII - Empty-Handed

XXXIV - The Revelations of a Man Who Hanged Himself

XXXV - The Arrests

XXXVI - George

XXXVII - The Duc d’Enghien [2]

XXXVIII - Chateaubriand

XXXIX - The Embassy in Rome

XL - Resolve

XLI - Via Dolorosa

XLII - Suicide

XLIII - The Trial

XLIV - In the Temple

XLV - In the Courtroom

XLVI - The Sentencing

XLVII - The Execution

PART II - NAPOLEON

XLVIII - After Three Years in Prison

XLIX - Saint-Malo

L - Madame Leroux’s Inn

LI - The Fake English Ship

LII - Surcouf

LIII - The Officers on the Revenant

LIV - Getting Under Way

LV - Tenerife

LVI - Crossing the Line

LVII - The Slave Ship

LVIII - How the American Captain Got Forty-Five Thousand Francs instead of the Five Thousand He Was Asking For

LIX - Île de France

LX - On Land

LXI - The Return [I]

LXII - The New York Racer

LXIII - The Guardian

LXIV - Malay Pirates

LXV - Arrival

LXVI - Pegu

LXVII - The Trip

LXVIII - The Emperor Snake

LXIX - Brigands

LXX - The Steward’s Family

LXXI - The Garden of Eden

LXXII - The Colony

LXXIII - The Vicomte de Sainte-Hermine Is Buried

LXXIV - Tigers and Elephants

LXXV - Jane’s Illness

LXXVI - Delayed Departure

LXXVII - Indian Nights

LXXVIII - Preparations for a Wedding

LXXIX - The Wedding

LXXX - Eurydice

LXXXI - Return to Pegu

LXXXII - Two Captures

LXXXIII - Return to Chien-de-Plomb

LXXXIV - A Visit to the Governor

LXXXV - A Collection for the Poor

LXXXVI - Departure

LXXXVII - What Was Happening in Europe

LXXXVIII - Emma Lyonna

LXXXIX - In Which Napoleon Sees That Sometimes It Is More Difficult to Control Men Than Fortune

XC - The Port of Cadiz

XCI - The Little Bird

XCII - Trafalgar

XCIII - Disaster

XCIV - The Storm

XCV - Escape

XCVI - At Sea

XCVII - Monsieur Fouché’s Advice

XCVIII - A Relay Station in Rome

XCIX - The Appian Way

C - What Was Happening on the Appian Way Fifty Years before Christ

CI - An Archeological Conversation between a Navy Lieutenant and a Captain of Hussars

CII - In Which the Reader Will Guess the Name of One of the Two Travelers and Learn the Name of the Other

CIII - The Pontine Marshes

CIV - Fra Diavolo

CV - Pursuit

CVI - Major Hugo

CVII - At Bay

CVIII - The Gallows

CIX - Christophe Saliceti, Minister of Police and Minister of War

CX - King Joseph

CXI - Il Bizzarro

CXII - In Which the Two Young Men Part Ways, One to Return to Service under Murat, and the Other to Request Service under Reynier

CXIII - General Reynier

CXIV - In Which René Sees that Saliceti Was Not Mistaken

CXV - The Village of Parenti

CXVI - The Iron Cage

CXVII - In Which René Comes Upon Il Bizzarro’s Trail When He Least Expects It

CXVIII - In Pursuit of Bandits

CXIX - The Duchess’s Hand

APPENDIX

I His Imperial Highness, Viceroy Eugene-Napoleon (#litres_trial_promo)

II At Lunch (#litres_trial_promo)

III Preparations (#litres_trial_promo)

A NOTE TO THE READER

A NOTE ABOUT PREPARING THE TEXT

About the Author

By the same author

Copyright

About the Publisher

PART I BONAPARTE (#u3e8154c2-e160-5506-b2f3-078402a93490)

I Josephine’s Debts (#u3e8154c2-e160-5506-b2f3-078402a93490)

“NOW THAT WE ARE in the Tuileries,” Bonaparte, the First Consul, said to Bourrienne, his secretary, as they entered the palace where Louis XVI had made his next-to-last stop between Versailles and the scaffold, “we must try to stay.”

Those fateful words were spoken at about four in the afternoon on the 30th Pluviose in the Revolutionary year VIII (February 19, 1800).

This narration begins exactly one year to the day after the First Consul’s installation. It follows our book The Whites and the Blues, which ended, as we recall, with Pichegru fleeing from Sinnamary, and our novel The Companions of Jehu, which ended with the execution of Ribier, Jahiat, Valensolles, and Sainte-Hermine.

As for General Bonaparte, who was not yet general at that time, we left him just after he had returned from Egypt and landed back on French soil. Since the 24th Vendémiaire in the year VII he had accomplished a great deal.

First of all, he had managed and won the 18th Brumaire, though the case is still being appealed before posterity.

Then, like Hannibal and Charlemagne, he crossed the Alps.

Later, with the help of Desaix and Kellermann, he won the battle of Marengo, after first losing it.

Then, in Lunéville, he arranged peace.

Finally, on the same day that he had David’s bust of Brutus placed in the Tuileries, he re-established the use of “madame” as a form of address. Stubborn people were still free to use the word “citizen” if they wanted, but only yokels and louts still said “citizeness.”

And of course only the proper sort of people came to the Tuileries.

Now it’s the 30th Pluviose in the year IX (February 19, 1801), and we are in the First Consul Bonaparte’s palace in the Tuileries.

We shall now give the present generation, two thirds of a century later, some idea of his study where so many events were planned. With our pen we shall draw as best we can the portrait of that legendary figure who was considering not only how to change France but also how to turn the entire world upside down.

His study, a large room painted white with golden moldings, contains two tables. One, quite beautiful, is reserved for the First Consul; when seated at the table, he has his back to the fireplace and the window to his right. Also on the right is a small office where Duroc, his trusty aide-de-camp of four years, works. From that room they can communicate with Landoire, the dependable valet who enjoys the First Consul’s total confidence, and with the large apartments that open up onto the courtyard.

The First Consul’s chair is decorated with a lion’s head, and the right armrest is damaged because he has often dug into it with his penknife. When he is sitting at his table, he can see in front of him a huge library packed with boxes from ceiling to floor.

Slightly to the right, beside the library, is the room’s second large door. It opens up directly to the ceremonial bedroom, from which one can move into the grand reception room. There, on the ceiling, Le Brun painted Louis XIV in full regalia, and there a second painter, certainly not as gifted as Le Brun, had the audacity to add a Revolutionary cockade to the great king’s wig. Bonaparte is in no rush to remove it because it allows him to say, when he points out the anomaly to visitors: “Those men from the Convention years were certainly idiots!”

Opposite the study’s only window, which allows light into this quite sizable room and looks out over the garden, stands a large wardrobe that’s attached to the consular office. It is none other than Marie de Médicis’s oratory, and it leads to a small stairway that descends to Madame Bonaparte’s bedroom below.

Just like Marie-Antoinette, whom she resembles in more ways than one, Josephine hates the state apartments. Consequently, she has arranged her own little safe haven in the Tuileries, as had Marie-Antoinette at Versailles.

Almost always, at least at the time we are speaking of, the First Consul would enter his office in the morning through that wardrobe. We say “almost always,” because after they moved to the Tuileries the First Consul also had a bedroom separate from Josephine’s. He slept there if he came home too late at night, so as not to disturb his wife, or if some subject of discord—and such moments, though not yet frequent, were beginning to occur from time to time—had precipitated an argument that left them for a time not on speaking terms.

The second table is nondescript. Placed near the window, it affords the secretary a view of thick chestnut tree foliage, but in order to see whoever may be walking in the garden he has to stand up. When he is seated, his back is turned just slightly to the First Consul, so the secretary has to turn his head only a bit to see him. As Duroc is rarely in his office, that is where the secretary often receives visitors.

Bourrienne is that secretary.

The most skillful artists competed with each other to paint or sculpt Bonaparte’s, and later Napoleon’s, features. But the men who lived most closely with him, although they could recognize in such statues or portraits the extraordinary man’s essence, say that no single image of the First Consul or the Emperor exists that is a perfect likeness.

When he was First Consul, they managed to paint or sculpt his prominent cranium, his magnificent brow, the hair that he plastered down over his temples and let fall to his shoulders, his tanned face, long and thin, with its meditative physiognomy.

As Emperor, in their depictions, his head resembles an antique medallion and his pale, unhealthy skin marks a man who will die young. They could draw his hair as black as ebony, to show off his dark complexion to full effect, but neither the chisel nor the brush could render the dancing flames in his eyes or capture the somber cast of his features when he was in deep thought.

With the speed of lightning the expression in his eyes obeyed his will. In anger, nobody looked more fearsome; in kindness, no one’s gaze was more caressing. Indeed, for each thought that traversed his soul he had a different expression.

He was short of stature, scarcely five feet three inches tall, and yet Kléber, who stood a head taller than he, once said to him as he placed his hand on his shoulder, “General, you are as big as the world!” And at that moment he did seem truly a head taller than Kléber.

He had lovely hands. He was proud of his hands and cared for them as a woman might have done. In conversation, he would frequently glance at them with admiration. Only on his left hand would he wear a glove; he kept his right hand bare, ostensibly so it would be ready should he want to reach out to someone he might choose to so honor, but in reality it was so he could admire his hand and shine his nails with a cambric handkerchief. Monsieur de Turenne, part of whose job it was to help the Emperor dress, came to the point where he would order gloves only for his left hand, thus saving six thousand francs a year.

He could not stand inactivity. Even in his private apartments he would constantly pace up and down, all the while leaning slightly forward, as if the weight of every thought in his head was forcing his neck to bend, and holding his hands clasped behind his back. His right shoulder would frequently jerk, and at the same time the muscles in his mouth would tighten. These ticks, these habits of mind and body, some people mistook for convulsive movements from which they deduced that Bonaparte must be subject to epileptic attacks.

He was passionate about bathing. Sometimes he would stay in his bath for two or three hours while the secretary or an aide read him the newspapers or a pamphlet the police had brought to his notice. Once he was in his bath, he would leave the hot faucet open, with no concern if the bath overflowed. Often, when Bourrienne, soaked with steam, could bear it no longer, he would ask if he could open the window or leave the room. In general, his request was granted.

Bonaparte truly loved to sleep. When his secretary woke him at seven, he would frequently complain, saying: “Oh, just let me sleep a little longer.” “Don’t come into my bedroom at night,” he would say. “Never wake me up for good news, for there’s no hurry to hear good news. But if ever there is bad news, wake me up immediately, for then there’s not a moment to be lost.”

As soon as Bonaparte was arisen, his valet Constant would shave him and brush his hair. Bourrienne, meanwhile, would read him the newspapers, first Le Moniteur and then the English or German papers. Bourrienne would barely have read the headlines from one of the dozen French newspapers being published at that time before Bonaparte would say: “That’s enough; they say only what I let them say.”

Once he was dressed and ready for the day, he would go up to his study along with Bourrienne. There he would find the letters he would need to read that day and the reports from the day before that he would need to sign.

At exactly ten o’clock the door would open and the butler would announce: “The general is served.”

Breakfast was simple, only three dishes plus dessert. One of the dishes was almost always the chicken prepared with oil and onions that he had been served as well on the morning of the Battle of Marengo, and since that day the dish has been called chicken Marengo.

Bonaparte drank only a little wine, a Bordeaux or Burgundy, and then, after breakfast or dinner, he would have a cup of coffee. If he worked unusually late at night, at midnight he would have a cup of chocolate.

Early on, he began to use tobacco, but only three or four times a day, in very small amounts, and he always carried it in very elegant gold or enamel boxes.

On this particular day early in our Revolutionary year IX, as usual, Bourrienne had come down to the study at six thirty, opened the letters, and placed them on the large table, the most important ones on the bottom, so that Bonaparte would read them last and they would be fresh in his mind.

When the clock struck seven, he went to wake the general. Bourrienne had a key to Bonaparte’s bedroom, so he could enter whenever necessary, at any time of day or night.

To his great surprise, he found Madame Bonaparte alone in bed. She was weeping.

Bourriene’s first instinct was to turn and leave. But Madame Bonaparte, who admired Bourrienne and knew that she could count on him, stopped him. She asked him to sit down on the bed beside her.

Bourrienne was worried. “Oh, madame,” he asked. “Has anything happened to the First Consul?”

“No, Bourrienne, no,” Josephine had answered. “Something has happened to me.”

“What, madame?”

“Oh, my dear Bourrienne. How unfortunate I am!”

Bourrienne began to laugh. “I bet I can guess what’s wrong,” he said.

“My suppliers,” stammered Josephine.

“Are they refusing to supply you?”

“Oh, if that’s all it was!”

“Could they be so impertinent as to ask to be paid?” asked Bourrienne with a laugh.

“They are threatening to sue me! Imagine how embarrassing it would be for me, my dear Bourrienne, if an official order landed in Bonaparte’s hands!”

“Do you think they would dare?”

“There is no doubt in my mind.”

“Impossible!”

“Look here.”

And out from under her pillow Josephine pulled a sheet of paper imprinted with a symbol of the Republic. It was an official summons demanding of the First Consul the sum of forty thousand francs in payment for gloves delivered to Madame Bonaparte his wife. As chance would have it, the order had fallen into Madame Bonaparte’s hands rather than her husband’s. The proceedings were being carried out on behalf of Madame Giraud.

“Damn!” said Bourrienne. “This is serious! Did you authorize your entire household to buy gloves from that woman?”

“No, my dear Bourrienne; those forty thousand francs worth of gloves were for me alone.”

“For you alone?”

“Yes.”

“You must not have paid anything for ten years!”

“I settled accounts with all my suppliers and paid them last year on the first of January. I paid three hundred thousand francs. I remember how angry Bonaparte was then, which is why I’m quaking now.”

“And you have worn forty thousand francs worth of gloves since the first of January last year?”

“Apparently so, Bourrienne, since that’s what they’re asking.”

“Well, then, what you expect me to do about it?”

“If Bonaparte is in good humor this morning, perhaps you could bring up the subject with him.”

“First of all, why is he not here with you? Have you quarreled?” Bourrienne asked.

“No, not at all. He was feeling fine last night when he left with Duroc to check out, as he says, what Parisians are thinking about. He probably came home late and, not wishing to disturb me, went to sleep in his bachelor’s quarters.”

“And if he is in good humor and I do speak to him of your debts, when he asks me how much you owe, how shall I answer?”

“Ah, Bourrienne!” Josephine hid her face behind her sheet.

“So, the figure is frightening?”

“Enormous.”

“How much?”

“I don’t dare tell you.”

“Three hundred thousand francs?”

Josephine gave a sigh.

“Six hundred thousand?”

Another sigh, even heavier than the first.

“I must say that you are indeed beginning to frighten me,” said Bourrienne.

“I spent the whole night adding sums up with my dear friend Madame Hulot, who is very good at such things. As you know, Bourrienne, I don’t have a head for figures.”

“So how much do you owe?”

“More than twelve hundred thousand francs.”

Bourrienne gave a start. “You’re right,” he said, and he was no longer laughing. “The First Consul will indeed be furious.”

“Let’s just tell him it’s half that amount.”

“Not a good strategy,” said Bourrienne shaking his head. “While you’re at it, I advise you to admit everything.”

“No, Bourrienne. Never!”

“But what will you do about the other six hundred thousand francs?”

“First of all, I shall contract no more debts, because they make me too unhappy.”

“But how about the other six hundred thousand?” Bourrienne asked again.

“I shall pay them out of what I can save.”

“That won’t work. Since the First Consul is not expecting the figure of six hundred thousand francs, he will make no more of a fuss for twelve hundred thousand than for six. On the contrary, since the blow is more violent, he will be in even greater shock. He will give you the twelve hundred thousand francs, and you will be over and done with it.”

“No, no,” cried Josephine. “Don’t make me do that, Bourrienne. I know him too well. He’ll fly into one of his rages, and I can’t stand seeing him get so violent.”

At that moment Bonaparte’s bell rang for his office boy, probably to find out where Bourrienne was.

“That’s him,” said Josephine. “He’s already in his study. Hurry, and if he’s in a good mood, you know.…”

“Twelve hundred thousand francs, right?”

“Heavens, no! Six hundred thousand, and not a penny more!”

“That’s what you wish?”

“Please.”

“Very well.”

And Bourrienne hurried up the little staircase to the First Consul’s study.

II How the Free City of Hamburg Paid Josephine’s Debts (#u3e8154c2-e160-5506-b2f3-078402a93490)

WHEN BOURRIENNE RETURNED to the study, the First Consul was reading the morning mail that the secretary had laid out for him on his desk. He was wearing the uniform of a Republican division general, a frock coat without epaulettes with a simple gold laurel branch, buckskin pants, a red vest with wide lapels, and boots with their tops turned down. At the sound of his secretary’s footsteps, Bonaparte turned his head.

“Oh, it’s you, Bourrienne,” he said. “I was just ringing Landoire to have him call you.”

“I had gone down to Madame Bonaparte’s room, thinking I would find you there, General.”

“No, I slept in the large bedroom.”

“Ah,” said Bourrienne. “In the bed that belonged to the Bourbons!”

“Well, yes.”

“And how did you sleep?”

“Poorly. And the proof is that I’m already here and you did not have to awaken me. It’s all too comfortable for me.”

“Have you read the three letters I set aside for you, General?”

“Yes, the wife of a sergeant-major in the consular guard who was killed at Marengo is asking me to be the godfather of her child.”

“How should I answer her?”

“Tell her I accept. Duroc can stand in for me. The child’s name will be Napoleon. The mother will receive an annuity of five hundred francs that will revert to her son. Answer her in those terms.”

“And how about the woman who, believing in your good luck, asks you for three lottery numbers?”

“She’s crazy. But since the woman believes in my star and is sure she’ll win if I send her three numbers, though she has never won before, tell her that you can only win the lottery on those days you don’t bet anything. As proof tell her that she has never won anything when she has bought tickets, but on the day that she has not bought a ticket she has won three hundred francs.”

“So, I am to send her three hundred francs?”

“Yes.”

“And the last letter, General?”

“I was just beginning to read it when you came in.”

“Keep reading; you will find it interesting.”

“Read it to me. The writing is scribbly and difficult to read.”

With a smile, Bourrienne picked up the letter. “I know why you’re smiling,” said Bonaparte.

“Ah, I don’t think you do, General,” replied Bourrienne.

“You’re no doubt thinking that someone with handwriting like mine should be able to read anyone’s, even the scribbling of cats and public prosecutors.”

“Well, you’re right.”

Bourrienne began to read:

“‘Jersey, February 26, 1801

“‘I believe, General, that since you are back from your extensive voyages, I can now, without being indiscreet, interrupt your daily occupations by reminding you who I am. However, you may be surprised that such a feeble excuse is the subject of the letter I have the honor of addressing you. You will remember, General, that when your father was forced to take your brothers out of the school in Autun and came to see you in Brienne, he found himself penniless. He asked me to lend him twenty-five louis, which I was pleased to do. Since his return, he has not had the opportunity to pay me back, and when I left Ajaccio, your good mother offered to give up some of her silver to reimburse me. I rejected her offer and told her that I would leave the promissory note signed by your father with Monsieur Souires and that she should pay it when she was able and it convenient. I judge that she had not yet found the appropriate time to do so when the Revolution took place.

“‘You may find it strange, General, that for such a modest sum I am willing to trouble your occupations. But my situation is very difficult just now, and even such a small amount seems large to me. Exiled from my country, forced to find refuge on this island I abhor, where everything is so expensive that one has to be rich to live even simply, I would deem it a great kindness on your part if you would enable me to have that tiny sum which in earlier days would have been meaningless to me.’”

Bonaparte nodded. Bourrienne noticed his reaction.

“Do you remember this good man, General?” he asked.

“Perfectly well,” said Bonaparte. “As if it were yesterday. The sum was counted out in Brienne before my very eyes. His name must be Durosel.”

Bourrienne looked down at the signature. “That’s right,” he said. “But there’s another name, one more illustrious than the first.”

“What is his full name, then?”

“Durosel Beaumanoir.”

“We must find out if he’s from the Beaumanoir family in Brittany. That’s a good name to have.”

“Shall I keep reading?”

“Go ahead.”

Bourrienne continued:

“‘You will understand, General, that when a man is eighty-six years old and has served his country for more than sixty years without the slightest interruption, it is difficult to be sent away and forced to find refuge on Jersey, where I try to subsist on the government’s feeble attempts to help French émigrés.

“‘I use the word “émigrés” because that is what I was forced to become. Leaving France had never been in my plans, and I had committed no crime except for being the most senior general in the canton and being decorated with the great cross of Saint-Louis.

“‘One evening they came to kill me. They broke down my door. I was alerted by my neighbors’ shouts and barely had the time to escape with nothing but the clothes I had on my back. Seeing that I risked death in France, I abandoned all that I owned, real estate and furniture, and since I had no place to put my feet in my own country, I joined one of my older brothers here. He had been deported and was senile, and now I wouldn’t leave him for anything in the world. My mother-in-law is eighty years old, and they have refused to give her a portion of my estate, on the pretext that everything I owned had been confiscated. Thus, if things don’t change, I shall die bankrupt, and that saddens me greatly.

“‘I admit, General, that I have not adapted to the new style, but according to former customs,

“‘I am your humble servant.

“‘Durosel Beaumanoir’”

“Well, General, what do you say?”

“I say,” the First Consul replied with a slight catch in his voice, “that I am profoundly moved to hear such things. This is a sacred debt, Bourrienne. Write to General Durosel, and I shall sign the letter. Send him ten thousand francs and say that he can expect more, for I would like to do more for this man who helped my father. I shall take care of him. But, speaking of debts, Bourrienne, I have some serious business to talk about with you.” Bonaparte sat down with a frown.

Bourrienne remained standing near his chair. Bonaparte said, “I want to talk to you about Josephine’s debts.”

Bourrienne gave a start. “Very well,” he said. “And where do you get your information?”

“From what I hear in public.”

Like a man who has not fully understood but who dares ask no questions, Bourrienne leaned forward.

“Just imagine, my friend”—Bonaparte sometimes forgot himself and dropped formal address—“that I went out with Duroc to find out for myself what people are saying.”

“And are they saying many negative things about the First Consul?”

“Well,” Bonaparte answered with a laugh, “I nearly got myself killed when I said something bad about him. Without Duroc, who used his club, I believe we might have been arrested and taken to the Château-d’Eau guardhouse.”

“Still, that fails to explain how, in the midst of all the praise for the First Consul, the question of Madame Bonaparte’s debts came up.”

“In fact, in the midst of all that praise for the First Consul, people were saying horrible things about his wife. They’re saying that Madame Bonaparte is ruining her husband with all the clothes she’s buying; they’re saying she has debts everywhere, that her cheapest dress cost one hundred louis and her least expensive hat two hundred francs. I don’t believe a word of that, Bourrienne, you understand. But where there’s smoke, there’s fire. Last year I paid debts of three hundred thousand francs; she reminded me that I had not sent her any money from Egypt. All well and good. But now things are different; I’m giving Josephine six thousand francs a month for clothes. That should be enough. People used the same kinds of words against Marie-Antoinette. You must check with Josephine, Bourrienne, and set things straight.”

“You’ll never know,” Bourrienne answered, “how happy I am that you yourself have brought up this subject. This morning, as you were impatiently waiting for me to appear, Madame Bonaparte asked me to talk to you about the difficult position in which she finds herself.”

“Difficult position, Bourrienne! What do you mean by that, monsieur?” Bonaparte asked, suddenly reverting back to more formal speech.

“I mean that she is being harassed.”

“By whom?”

“By her creditors.”

“Her creditors! I thought I had got rid of her creditors.”

“A year ago, yes.”

“Well?”

“Well, in the past year, things have totally changed. One year ago she was the wife of General Bonaparte. Today she is the wife of the First Consul.”

“Bourrienne, that’s enough. My ears have heard enough of prattle.”

“That’s my opinion, General.”

“It is up to you to take care of paying everything.”

“I would be happy to. Give me the necessary sum, and I shall quickly take care of it, I guarantee.”

“How much do you need?”

“How much do I need? Well, yes.…”

“Well?”

“Well, Madame Bonaparte doesn’t dare tell you.”

“What? She doesn’t dare tell me? And how about you?”

“Nor do I, General.”

“Nor do you! Then it must be a colossal amount!”

Bourrienne sighed.

“Let’s see now,” Bonaparte continued. “If I pay for this year like last year, and give you three hundred thousand francs.…”

Bourrienne didn’t say a word. Bonaparte looked at him worriedly. “Say something, you imbecile!”

“Well, if you give me three hundred thousand francs, General, you would be giving me only half of the debt.”

“Half!” shouted Bonaparte, getting to his feet. “Six hundred thousand francs! … She owes … six hundred thousand francs?”

Bourrienne nodded.

“She admitted she owed that amount?”

“Yes, General.”

“And where does she expect me to get the money to pay these six hundred thousand francs? From my five-hundred-thousand-franc salary as consul?”

“Oh, she assumes you have several thousand franc bills hid somewhere in reserve.”

“Six hundred thousand francs!” Bonaparte repeated. “And at the same time my wife is spending six hundred thousand francs on clothing, I’m giving one hundred francs as pension to the widow and children of brave soldiers killed at the Pyramids or Marengo! And I can’t even give money to all of them! And they have to live the whole year on those one hundred francs, while Madame Bonaparte wears dresses worth one hundred louis and hats worth twenty-five. You must have heard incorrectly, Bourrienne, it surely cannot be six hundred thousand francs.”

“I heard perfectly well, General, and Madame Bonaparte realized what her situation was only yesterday when she saw a bill for gloves that came to forty thousand francs.”

“What are you saying?” shouted Bonaparte.

“I’m saying forty thousand francs for gloves, General. What do you expect? That is how things are. Yesterday she went over her accounts with Madame Hulot. She spent the night in tears, and she was still weeping this morning when I saw her.”

“Well, let her cry! Let her cry with shame, or even out of remorse! Forty thousand francs for gloves! Over how many months?”

“Over one year,” Bourrienne answered.

“One year! That’s enough food for forty families! Bourrienne, I want to see all those bills.”

“When?”

“Immediately. It’s eight o’clock, and I don’t see Cadoudal until nine, so I have the time. Immediately, Bourrienne. Immediately!”

“You’re quite right, General. Now that we have started, let’s get to the end of this business.”

“Go get all the bills, all of them, you understand. We shall go through them together.”

“I’m on my way, General.” And Bourrienne ran down the stairway leading to Madame Bonaparte’s apartment.

Left alone, the First Consul began to pace up and down, his hands clasped behind his back, his shoulder and mouth twitching. He started mumbling to himself: “I ought to have remembered what Junot told me at the fountains in Messoudia. I ought to have listened to my brothers Joseph and Lucien who told me not to see her when I got back. But how could I have resisted seeing my dear children Hortense and Eugene? The children brought me back to her! Divorce! I shall keep divorce legal in France, if only so I can leave that woman. That woman who gives me no children, and she’s ruining me!”

“Well,” said Bourrienne as he reentered the study, “six hundred thousand francs won’t ruin you, and Madame Bonaparte is still young enough to give you a son who in another forty years will succeed you as consul for life!”

“You have always taken her side, Bourrienne!” said Bonaparte, pinching his ear so hard the secretary cried out.

“What do you expect, General? I’m for everything that is beautiful, good, and feeble.”

In a rage, Bonaparte grabbed up the handful of papers from Bourrienne and twisted them back and forth in his hands. Then, randomly, he picked up a bill and read: “‘Thirty-eight hats’ … in one month! What’s she doing, wearing two hats a day? And eighteen hundred francs worth of feathers! And eight hundred more for ribbons!” Angrily, he threw down the bill and picked up another. “Mademoiselle Martin’s perfume shop. Three thousand three hundred and six francs for rouge. One thousand seven hundred forty-nine francs during the month of June alone. Rouge at one hundred francs a jar! Remember that name, Bourrienne. She’s a hussy who should be sent to prison in Saint-Lazare. Mademoiselle Martin, do you hear?”

“Yes, General.”

“Oh, now we come to the dresses. Monsieur Leroy. Back in the old days there were seamstresses, now we have tailors for women—it’s more moral. One hundred fifty dresses in one year. Four hundred thousand francs worth of dresses! If things keep going like this, it won’t be six hundred thousand francs, it’ll be a million. Twelve hundred thousand francs at the least that we’ll have to deal with.”

“Oh, General,” Bourrienne hastily said, “there have been some down payments made.”

“Three dresses at five thousand francs apiece!”

“Yes,” said Bourrienne. “But there are six at only five hundred each.”

“Are you making fun of me?” said Bonaparte with a frown.

“No, General, I’m not making fun of you. All I’m saying is that it’s beneath you to get so upset for nothing.”

“How about Louis XVI? He was a king, and he got upset. And he had a guaranteed income of twenty-five million francs.”

“You are—or at least when you want to be, you will be—more of a king than Louis XVI ever was, General. Furthermore, Louis XVI was an unfortunate man, you’ll have to admit.”

“A good man, monsieur.”

“I wonder what the First Consul would say if people said he was a good man.”

“For five thousand francs at least they could give us one of those beautiful gowns from Louis XVI’s days, with hoops and swirls and panniers, gowns that needed fifty meters of cloth. That I could understand. But with these new, simple frocks—women look like umbrellas in a case.”

“They have to follow the styles, General.”

“Exactly, and that is what makes me so angry. We’re not paying for cloth. At least if we were paying for the cloth, it would mean business for our factories. But no, it’s the way Leroy cuts the dress. Five hundred francs for cloth and four thousand five hundred francs for Leroy. Style! … So now we have to find six hundred thousand francs to pay for style.”

“Do we not have four million?”

“Four million? Where?”

“The money the Hamburg senate has just paid us for allowing the extradition of those two Irishmen whose lives you saved.”

“Oh, yes. Napper – Tandy and Blackwell.”

“I believe there may in fact be four and half million francs, not just four million, that the senate sent to you directly through Monsieur Chapeau-Rouge.”

“Well,” said Bonaparte with a laugh, delighted by the trick he had played on the free city of Hamburg, “I don’t know if I really had the right to do what I did, but I had just come back from Egypt, and that was one of the little tricks I’d taught the pashas.”

Just then the clock struck nine. The door opened, and Rapp, who was on duty, announced that Cadoudal and his two aides-de-camp were waiting in the official meeting room.

“Well, then, that’s what we’ll do,” said Bonaparte to Bourrienne. “That’s where you can get your six hundred thousand francs, and I don’t want to hear another word about it.” And Bonaparte went out to receive the Breton general.

Scarcely had the door closed than Bourrienne rang the bell. Landoire rushed in. “Go tell Madame Bonaparte that I have some good news for her, but since I don’t dare leave my office, where I am alone—you understand, Landoire; where I am alone—I would like to ask her to come see me here.”

When he realized it was good news, Landoire hurried to the staircase.

Everyone, from Bonaparte on down, adored Josephine.

III The Companions of Jehu (#ulink_ed629a3f-b279-58d1-b096-7dc320829525)

IT WAS NOT THE FIRST TIME that Bonaparte tried to bring Cadoudal back to the side of the Republic in order to gain that formidable partisan’s support.

An incident that had occurred on Bonaparte’s return from Egypt was imprinted deeply in his memory.

On the 17th Vendémiaire of the year VIII (October 9, 1799), Bonaparte had, as everyone knows, disembarked in Fréjus without going through quarantine, although he was coming from Alexandria.

He had immediately gotten into a coach with his trusted aide-de-camp, Roland de Montrevel, and left for Paris.

The same day, around four in the afternoon, he reached Avignon. He stopped about fifty yards from the Oulle gate, in front of the Hôtel du Palais-Egalité, which was just beginning again to use the name Hôtel du Palais-Royal, a name it had held since the beginning of the eighteenth century and that it still holds today. Urged by the need all mortals experience between four and six in the afternoon to find a meal, any meal, whatever the quality, he got down from the coach.

Bonaparte was in no particular way distinguishable from his companion, save for his firm step and his few words, yet it was he who was asked by the hotel keeper if he wished to be served privately or if he would be willing to eat at the common table.

Bonaparte thought for a moment. News of his arrival had not yet spread through France, as everyone thought he was still in Egypt. His great desire to see his countrymen with his own eyes and hear them with his own ears won out over his fear of being recognized; besides, he and his companion were both wearing clothing typical for the time. Since the common table was already being served and he would be able to dine without delay, he answered that he would eat at the common table.

He turned to the postilion who had brought him. “Have the horses harnessed in one hour,” he said.

The hotelier showed the newcomers the way to the common table. Bonaparte entered the dining room first, with Roland behind him. The two young men—Bonaparte was then about twenty-nine or thirty years old, and Roland twenty-six—sat down at the end of the table, where they were separated from the other diners by three or four place settings.

Whoever has traveled knows the effect created by newcomers at a common table. Everyone looks at them, and they immediately become the center of attention.

At the table were some regular customers, a few travelers en route by stagecoach from Marseille to Lyon, and a wine merchant from Bordeaux who was staying temporarily in Avignon.

The great show the newcomers had made of sitting off by themselves increased the curiosity of which they were the object. Although the man who’d entered second was dressed much the same as his companion—short leather pants and turned-down boots, a coat with long tails, a traveler’s overcoat and a wide-brimmed hat—and although they appeared to be equals, he seemed to show a noticeable deference to his companion. The deference was obviously not due to any age difference, so no doubt it was owed by a difference in social position. Furthermore, he addressed the first man as “citizen,” while his companion called him simply Roland.

What usually happens in such situations happened here. After a moment of interaction with the newcomers, everyone soon looked away, and the conversation, interrupted for a moment, resumed as before.

The subject of the conversation greatly interested the newly arrived travelers, as their fellow guests were talking about the Thermidorian Reaction and the hopes that lay in now reawakened Royalist feelings. They spoke openly of a coming restoration of the House of Bourbon, which surely, with Bonaparte being tied up as he was in Egypt, would take place within six months.

Lyon, one of the cities that had suffered hardest during the Revolution, naturally stood at the center of the conspiracy. There a veritable provisional government—with its royal committee and royal administration, a military headquarters and a royal army—had been set up.

But, in order to pay these armies and support the permanent war effort in the Vendée and Morbihan, they needed money; and lots of it. England had provided a little but was not overly generous, so the Republic was the only source of money available to its Royalist enemies. Instead of trying to open difficult negotiations with the Republic, which would have refused assistance in any case, the royal committee had organized roving bands of brigands who were charged with stealing tax revenues and with attacking the vehicles used for transporting public funds. The morality of civil wars, very loose in regard to money, did not consider stealing from Treasury stagecoaches as real theft, but rather as a military operation.

One of these bands had chosen the route between Lyon and Marseille, and as the two travelers were taking their place at the common table, the subject of conversation was the hold-up of a stagecoach carrying sixty thousand francs of government funds. The hold-up had taken place the day before on the road from Marseille to Avignon, between Lambesc and Port-Royal.

The thieves, if we can use that word for such nobly employed stagecoach robbers, had even given the coachman a receipt for what they took. They had made no attempt, either, to hide the fact that the money would be crossing France by more secure means than his stagecoach and that it would buy supplies for Cadoudal’s army in Brittany.

Such actions were new, extraordinary, and almost impossible for Bonaparte and Roland to believe, for they had been absent from France for two years. They did not suspect what deep immorality had found its way into all classes of society under the Directory’s bland government.

This particular incident had taken place on the very same road Bonaparte and his companion had just traveled, and the person telling the story was one of the principal actors in that highway drama: the wine merchant from Bordeaux.

Those who seemed to be most interested in all the details, aside from Bonaparte and his companion, who were happy simply to listen, were the people traveling in the stagecoach that had just arrived and was soon to leave. As for the other guests, the people who lived nearby, they had become so accustomed to these episodes that they could have been giving the details instead of listening to them.

Everyone was looking at the wine merchant, and, we must say, he was up to the task as he courteously answered all the questions put to him.

“So, Citizen,” asked a heavyset man whose tall, skinny, shriveled-up wife was pressing up against him, pale and trembling in fear, so much so that you could almost hear her bones knocking together. “You say that the robbery took place on the road we’ve just taken?”

“Yes, Citizen. Between Lambesc and Pont-Royal, did you notice a place where the road climbs between two hills, a place where there are many rocks?”

“Oh, yes, my friend,” the woman said, holding tight to her husband’s arm. “I did see it, and I even said, as you must remember, ‘This is a bad place. I’m glad we’re coming through during the day and not at night.’”

“Oh, madame,” said a young man whose voice exaggerated the guttural pronunciation of the time and who seemed to exercise a royal influence on the conversation of the common table, “you surely know that for the gentlemen called the Companions of Jehu there is no difference between day and night.”

“Indeed,” said the wine merchant, “it was in full daylight, at ten in the morning, that we were stopped.”

“How many of them were there?” the heavyset man asked.

“Four of them, Citizen.”

“Standing in the road?”

“No, they appeared on horseback, armed to the teeth and wearing masks.”

“That is their custom, that is their custom,” said the young man with the guttural voice. “And then they must have said, did they not?, ‘Don’t try to defend yourselves, and no harm will come to you. All we are after is the government’s money.’”

“Word for word, Citizen.”

“Yes,” continued the man who seemed to have all the information. “Two of them got down, handed their bridles to their companions, and asked the coachman to give them the money.”

“Citizen,” the large man said in amazement, “you’re telling the story as if you had witnessed it yourself!”

“Perhaps the gentleman was there,” said Roland.

The young man turned sharply toward the officer. “I don’t know, Citizen, if you intend to be impolite with me. We can speak about that after dinner. But, in any case, I am pleased to say that my political opinions are such that, unless you were intending to insult me, I would not consider your suspicion as an offense. However, yesterday morning at ten o’clock, when those gentlemen were stopping the stagecoach four leagues away, these gentlemen here can attest to the fact that I was having lunch at this very table, between the same two citizens who at this moment are doing me the honor of sitting at my right and my left.”

“And,” Roland continued, speaking this time to the wine merchant, “how many of you were in the stagecoach?”

“There were seven men and three women.”

“Seven men, not counting the coachman?” Roland repeated.

“Of course,” the man from Bordeaux answered.

“And with eight men you let yourself be robbed by four bandits? I congratulate you, monsieur.”

“We knew whom we were dealing with,” the wine merchant answered, “and we were not about to try to defend ourselves.”

“What?” Roland replied. “But you were dealing with brigands, with bandits, with highway robbers.”

“Not at all, since they had introduced themselves.”

“They had introduced themselves?”

“They said, ‘We are not brigands; we are the Companions of Jehu. It is useless to try to defend yourselves, gentlemen; ladies, don’t be afraid.’”

“That’s right,” said the young man at the common table. “It is their custom to let people know, so there can be no mistake.”

“Well,” Roland continued, while Bonaparte kept silent, “who is this citizen Jehu who has such polite companions? Is he their captain?”

“Sir,” said a man whose clothing looked very much like that of a secular priest, and who seemed to be a resident of the city as well as a regular at the common table, “if you were more acquainted than you seem to be in reading Holy Scripture, you would know that this citizen Jehu died some two thousand six hundred years ago, so that consequently, at the present time, he is unable to stop stagecoaches on the highway.”

“Sir priest,” Roland said, “since, in spite of the sour tone you are currently using with me, you seem to be well educated, allow a poor ignorant man to ask for some details about this Jehu who died twenty-six hundred years ago but is nevertheless honored by having companions who carry his name.”

“Sir,” the man of the church answered in the same clipped tone, “Jehu was a king of Israel, consecrated by Elisha on the condition that he punish the crimes of the house of Ahab and Jezebel and that he put to death all the priests of Baal.”

“Sir priest,” the young officer laughed, “thank you for the explanation. I have no doubt that it is accurate and certainly very scholarly. Except I have to admit that it has taught me very little.”

“What do you mean, Citizen?” said the regular customer at the table. “Don’t you understand that Jehu is His Majesty Louis XVIII, may God preserve him, consecrated on the condition that he punish the crimes of the Republic and that he put to death all the priests of Baal—that is, all the Girondins, the Cordeliers, the Jacobins, the Thermidorians; all those people who have played any part over the last seven years in this abominable state of affairs that we call the Revolution!”

“Well, sure enough!” said Roland. “Indeed, I am beginning to understand. But among those people the Companions of Jehu are supposed to be fighting, do you include the brave soldiers who pushed the foreigners back out of France and the illustrious generals who led the armies in the Tyrol, the Sambre-et-Meuse, and Italy?”

“Yes. Those men, and especially those men.”

Roland’s eyes grew hard, his nostrils dilated, he pinched his lips and started to stand up. But his companion grabbed his coat and pulled him back down, and the word “fool,” which he was about to throw in the face of his interlocutor, stayed between his teeth.

Then, with a calm voice, the man who had just demonstrated his power over his companion spoke for the first time. “Citizen,” he said, “please excuse two travelers who have just come from the ends of the earth, as far away as America or India, who have been out of France for two years, who don’t know what’s happening here, and who are eager to learn.”

“Tell us what you would like to know,” the young man asked, apparently having paid only the slightest attention to the insult Roland had been about to spit at him.

“I thought,” Bonaparte continued, “that the Bourbons were completely reconciled to exile. I thought the police were sufficiently well organized to keep bandits and robbers off the highways. And finally, I thought that General Hoche had completely pacified the Vendée.”

“But where have you been? Where have you been?” said the young man with a loud laugh.

“As I told you, Citizen, at the ends of the earth.”

“Well, then. Let me help you understand. The Bourbons are not rich; the émigrés, whose property has been sold, are ruined. It is impossible to pay two armies in the West and to organize one in the Auvergne mountains without any money. So the Companions of Jehu, by stopping stagecoaches and pillaging the coffers of our tax officers, have set themselves up as tax collectors for the Royalist generals. Just ask Charette, Cadoudal, and Teyssonnet.”

“But,” ventured the Bordeaux wine merchant, “if the gentlemen calling themselves the Companions of Jehu are only after the government’s money.…”

“Only the government’s money, not anyone else’s. Never have they robbed an ordinary citizen.”

“So yesterday,” the man from Bordeaux continued, “how did it happen, then, that along with the government’s money they also carried off a bag containing two hundred louis that belonged to me?”

“My dear sir,” the young man answered, “I’ve already told you that there must have been some mistake, and as sure as my name is Alfred de Barjols, that money will be returned to you some day.”

The wine merchant sighed deeply and shook his head like a man who, in spite of the reassurances people are giving him, still is not totally convinced.

But at that moment, as if the guarantee given by the young man who had revealed his own name and social rank had awakened the sensibilities of those for whom he was giving his guarantee, a horse galloped up to the front door. They could hear footsteps in the corridor; the dining room door was flung open, and a masked man, armed to the teeth, appeared in the doorway.

All eyes turned to him.

“Gentlemen,” he said, his voice breaking the deep silence that greeted his unexpected appearance, “is there among you a traveler named Jean Picot who was in the stagecoach that was stopped between Lambesc and Port-Royal by the Companions of Jehu?”

“Yes,” said the wine merchant in astonishment.

“Might you be that man, monsieur?” the masked man asked.

“That’s me.”

“Was nothing taken from you?”

“Yes, there was. I had entrusted a sack of two hundred louis to the coachman, and it was taken.”

“And I must say,” added Alfred de Barjols, “that just now this gentleman was telling us about his misfortune, considering his money lost.”

“The gentleman was mistaken,” said the masked stranger. “We are at war with the government, not with ordinary citizens. We are partisans, not thieves. Here are your two hundred louis, monsieur, and if ever a similar error should take place in the future, just remember the name Morgan.”

And with those words the masked man set down a bag of gold to the right of the wine merchant, politely said good-bye to those seated around the table, and walked out, leaving some of them in terror and the others in stupefaction at his daring.

At that moment word came to Bonaparte that the horses were harnessed and ready.

He stood and asked Roland to pay.

Roland dealt with the hotel keeper while Bonaparte got into the coach. Just as Roland was about to join his companion, he found Alfred de Barjols in his path.

“Excuse me, monsieur,” the young man said to him. “You were beginning to say something to me, but the word never left your lips. Might I know what kept you from pronouncing it?”

“Oh, monsieur,” said Roland, “the reason I held it back was simply that my companion pulled me back down by my coat pocket, and so as not to be disagreeable to him, I decided not to call you a fool.”

“If you intended to insult me in that way, monsieur, might I therefore consider that you have now done so?”

“If that should please you, monsieur.…”

“That does please me, because it offers me the opportunity to demand satisfaction.”

“Monsieur,” said Roland, “we are in a great hurry, my companion and I, as you can see. But I will be happy to delay my departure for an hour if you think one hour will be enough to settle this question.”

“One hour will be sufficient, monsieur.”

Roland bowed and hurried to the coach.

“Well,” said Bonaparte, “are you going to fight?”

“I could not do otherwise, General,” Roland answered. “But my adversary appears to be very accommodating. It should not take more than an hour. I shall hire a horse as soon as this business is over and shall surely catch up with you before you reach Lyon.”

Bonaparte shrugged.

“Hothead,” he said. And then, reaching out his hand, he added, “Try at least not to get yourself killed. I need you in Paris.”

“Oh, relax, General. Somewhere between Valence and Vienne I shall come tell you what happened.”

Bonaparte left.

About one league beyond Valence he heard a horse galloping behind him and ordered the coachman to stop.

“Oh, it’s you, Roland,” he said. “Apparently everything went well?”

“Perfectly well,” said Roland as he paid for his horse.

“Did you fight?”

“Yes, I did, General.”

“How?”

“With pistols.”

“And?”

“And I killed him, General.”

Roland took his place beside Bonaparte and the coach set off again at a gallop.

IV The Son of the Miller of La Guerche (#ulink_afea8b3d-2f96-5d87-8477-ecbc1d2a46f6)

BONAPARTE NEEDED ROLAND in Paris to help him organize the 18th Brumaire. Once the 18th Brumaire was over, what Bonaparte had heard and seen with his own eyes at the common table in Avignon came back to him. He resolved to do all he could to track down the Companions of Jehu and try to bring Cadoudal around to support the Republic.

It was Roland to whom Bonaparte entrusted that mission.

Roland left Paris, gathered some information in Nantes, and took the road toward La Roche-Bernard. There, he was able to get information that sent him to the village of Muzillac. For that is where Cadoudal could be found.

Let us enter the village with Roland. Let us walk up to the fourth thatched-roof house on the right and look in through an opening in one of the shutters. There we see a man dressed like a rich Morbihan peasant. His collar, his lapels, and the edges of his hat are trimmed with one gold stripe the width of a finger. His clothing is made of gray wool, with a green collar. His outfit is complete with Breton suspenders and leather gaiters coming up nearly to his knees. His saber is lying on a chair, and on the table a pair of pistols are within reach. The blaze in the fireplace reflects off two or three gun barrels.

The man is seated at the table. Light from a lamp shines on his face and on some papers he is attentively reading. His expression is open and joyous. Curly blond hair frames his face, his bright blue eyes give it life, and when he smiles, he displays two rows of white teeth that clearly have never needed to be touched by a dentist’s brush or tools. He is nearly thirty years old.

Like his fellow countryman Du Guesclin, he has a large, round head. Consequently, he is as well known by the name General Tête-Ronde as he is by the name George Cadoudal.

George was the son of a farmer in the parish of Kerléano. He had just finished an excellent education in the secondary school in Vannes when the Royalist insurrection’s first appeals were made. Cadoudal responded, gathered together his hunting and partying companions, led them across the Loire, and offered his services to Stofflet.

But Monsieur de Maulevrier’s former game warden had his prejudices. He did not like nobility and liked the bourgeoisie even less. Before agreeing to take Cadoudal, he wanted first to see him at work, and Cadoudal asked for nothing more.

Already the next day there was combat. When Stofflet saw Cadoudal charge the Blues without concern for their bayonets or guns, he could only say to Monsieur de Bonchamps, who was standing beside him, “If some cannonball doesn’t carry off that tête ronde, he will make a name for himself.” The name stuck with him.

George fought in the Vendée until Savenay was routed, when half of the Vendée army died on the battlefield and the other half faded away like smoke.

After three years of prodigious feats of strength, skill, and courage, he crossed back over the Loire and returned to the Morbihan.

Once back on his native soil, Cadoudal fought on his own account. As general-in-chief, he was adored by his soldiers, who obeyed him at a simple signal. Thus Stofflet’s prophecy came true. Replacing La Roche-Jacquelein, d’Elbee, Bonchamps, Lescure, Charette, and even Stofflet himself, Cadoudal became their chief rival in glory and their superior in force. He alone continues to fight against the government of Bonaparte, who has been consul for two months and is now about to leave for Marengo.

Three days ago, Cadoudal learned that General Brune, victor at Alkmaar and Castricum, savior of Holland, has been named general-in-chief of the Western armies. Now in Nantes, he is at all costs supposed to wipe out Cadoudal and his Chouans.

So, that being the case, Cadoudal has no choice but to take it upon himself to prove to the general-in-chief that he is not afraid and that intimidation is the last weapon that Brune should use against him.

At this particular moment he is dreaming up some brilliant maneuver with which to dazzle the Republicans. Suddenly he raises his head. He has heard a horse galloping. The horseman must surely be one of his own for to enter Muzillac without difficulty, he’d have had to pass through the Chouans spread out along the road from La Roche-Bernard.

The horseman stops at the front door of the thatched hut and comes face to face with George Cadoudal.

“Oh, it’s you, Branche-d’Or,” Cadoudal says. “Where have you come from?”

“From Nantes, General.”

“Any news?”

“Bonaparte’s aide-de-camp has come with General Brune on a special mission for you.”

“For me?”

“Yes.”

“Do you know his name?”

“Roland de Montrevel.”

“Have you seen him?”

“As I see you now.”

“What kind of man is he?”

“A handsome young man about twenty-six or twenty-eight years old.”

“And when is he getting here?”

“An hour or two after me, probably.”

“Have you alerted our men along the highway?”

“Yes. He will be able to pass freely.”

“Where is the Republican vanguard?”

“In La Roche-Bernard.”

“How many men are there?”

“Approximately one thousand.”

At that moment they heard a second horse galloping up. “Oh!” said Branche-d’Or, “can that be him already? That’s impossible!”

“No, because the man arriving now is coming from Vannes.”

The second horseman stopped by the door and entered as had the first. Although he was wrapped in a large coat, Cadoudal recognized him immediately. “Is that you, Coeur-de-Roi?” he asked.

“Yes, General.”

“Where are you coming from?”

“From Vannes, where you sent me to keep an eye on the Blues.”

“Well, what are they doing?”

“They are starving, and to get some food, General Harty is planning to steal our stores in Grand-Champ. The general himself will lead the expedition, and so they can move rapidly, the column will be made up of only one hundred men.”

“Are you tired, Coeur-de-Roi?”

“Never, General.”

“And how about your horse?”

“He has run hard but can surely cover three or four leagues more without collapsing. With two hours of rest.…”

“Two hours of rest and a double ration of oats, and then your horse will need to cover six leagues!”

“He can do it, General.”

“In two hours you will leave, and you must give the order in my name to evacuate the village of Grand-Champ at daybreak.”

Cadoudal paused for a moment and turned to listen. “Ah,” he said. “This time it must be him. I hear a horse galloping up on the La Roche-Bernard road.”

“It’s him,” said Branche-d’Or.

“Who?” asked Coeur-de-Roi.

“Someone the general is expecting.”

“Now, my friends, please leave me alone,” said Cadoudal. “You, Coeur-de-Roi, get to Grand-Champ as quickly as possible. You, Branche-d’Or, wait in the courtyard with thirty men ready to carry a message to all parts of the country. I trust you can arrange to have the best possible supper for two brought here to me.”

“Are you going out, General?”

“No, I’m simply going to meet the person who’s arriving. Quickly, go to the courtyard and stay out of sight!”

Cadoudal appeared on the threshold of the front door just as a horseman, bringing his mount to a stop, was looking around uncertainly.

“He’s right here, monsieur,” said George.

“Who is right here?” the horseman asked.

“The man you are looking for.”

“How did you guess that I’m looking for someone?”

“That is not difficult to see.”

“And the man I’m looking for.…”

“Is George Cadoudal. That is not hard to guess.”

“Huh,” responded the young man in surprise.

He jumped down from his horse and began to tether it.

“Oh, just throw the bridle over his neck,” said Cadoudal, “and don’t worry about him. You will find him here when you need him. Nothing ever gets lost in Brittany. You are on loyal ground.” And then, showing him the door, he said, “Please do me the honor of entering this humble hut, Monsieur Roland de Montrevel. I can offer you no other palace for tonight.”

However much Roland was master of himself, he was unable to hide his astonishment from George. More from the light of the fire that some invisible hand had just stirred up than from the light of the lamp, George could study the young man who was trying in vain to figure out how the person he was looking for, and at, had been notified of his arrival ahead of time. Judging that it would be inappropriate to display his curiosity, Roland sat down on the chair Cadoudal offered and stretched his boots out toward the fire in the fireplace.

“Are these your headquarters?” he asked.

“Yes, Colonel.”

“They are guarded in a strange way, it seems to me,” said Roland, looking around.

“Do you say that,” asked George, “because you didn’t meet a soul on the highway between La Roche-Bernard and here?”

“Not a soul, I must say.”

“That does not prove the highway was unguarded,” said George with a laugh.

“Well, then it was guarded by owls, for they seemed to be accompanying me from tree to tree. And if that is the case, General, I withdraw my comment.”

“Exactly,” Cadoudal replied. “Those owls are my sentinels. They have good eyes, and they have the advantage over men of being able to see in the dark.”

“Nonetheless, if I hadn’t taken care to get directions in La Roche-Bernard, I never would have found a soul to show me the road.”

“If at any place along the road you had called out, ‘Where might I find George Cadoudal?’ a voice would have answered, ‘In the town of Muzillac, the fourth house on the right.’ You saw no one, Colonel. However, there are now approximately fifteen hundred men who know that Monsieur Roland de Montrevel, the First Consul’s aide-de-camp, is meeting with the miller of Kerléano.”

“But if they know I’m the First Consul’s aide-de-camp, why did your fifteen hundred men allow me to pass?”

“Because they had received orders not only to allow you free passage but also to help you if you should need them.”

“So you knew I was coming?”

“I knew not only that you were coming but also why you were coming.”

“Well, then, there’s no reason for me to tell you.”

“Yes, there is. For hearing what you have to say will be a pleasure.”

“The First Consul wishes peace, but a general peace, not a partial one. He has signed a peace treaty with the Abbé Bernier, d’Autichamp, Châtillon, and Suzannet. He considers you a brave and loyal adversary and is saddened to see you alone continuing to stand up to him. So he has sent me here to talk to you directly. What are your conditions for peace?”

“Oh, my conditions are quite simple,” said Cadoudal, laughing. “If the First Consul gives the throne back to His Majesty Louis XVIII, and if he in turn becomes the king’s constable, his lieutenant-general, and head of his army and navy, at that very instant I shall convert our truce into a treaty of peace and, further, shall become the first soldier in his ranks.”

Roland shrugged. “But you surely know that’s impossible; the First Consul has already positively refused that request.”

“Well, that is why I am inclined to continue hostilities.”

“When?”

“Tonight. And you have arrived just in time to witness the spectacle.”

“But you do know that the generals d’Autichamp, Châtillon, and Suzannet as well as the Abbé Bernier have laid down their arms?”

“They are from the Vendée, and as Vendeans, they can do as they wish. I am Breton and a Chouan, and in the name of Bretons and Chouans I can do as I wish.”

“So you are condemning this unfortunate country to a war of extermination, General?”

“It is martyrdom, to which I convoke all Christians and Royalists.”

“General Brune is in Nantes with the eight thousand French prisoners the English have just turned over to us.”

“That is good fortune they would not enjoy with the Chouans, Colonel. The Blues have taught us not to take prisoners. As for the number of our enemies, it is not our custom to worry about that. Numbers are only a matter of details.”

“But you know that if General Brune and his eight thousand prisoners, together with the twenty thousand soldiers he is inheriting from General Hédouville, are insufficient, the First Consul is determined to march against you himself, with one hundred thousand men if necessary.”

“We shall be grateful for the honor he bestows upon us,” said Cadoudal, “and we shall try to prove to him that we are worthy adversaries.”

“He will burn down your cities.”

“We shall then withdraw to our thatched-roof huts.”

“He will burn down your huts.”

“We shall live in the woods.”

“You will give it some thought, General.”

“Please do me the honor of staying with me for twenty-four hours and you will see that I have already thought about it.”

“And if I agreed?”

“You would gratify me, Colonel. Only don’t ask more than I can give you: a bed under a thatched roof, one of my horses so you can accompany me, and a safe-conduct for when you leave.”

“I accept.”

“Your word, monsieur, never to act counter to the orders I give you, never to try to thwart any surprises I might attempt.”

“I am too curious about what you’ll be doing for that. You have my word, General.”

“Even when things happen before your very eyes?” asked Cadoudal insistently.

“Even if things take place before my very eyes, I renounce my role as an actor and will remain a spectator. I want to be able to say to the First Consul, ‘I saw.’”

Cadoudal smiled. “Well, you will see,” he said.

At that moment the door opened, and two peasants carried in a table already completely set. Steam was rising up from a crock of cabbage soup and a slab of bacon. An enormous jug of cider, newly drawn, foaming up and overflowing, stood between two glasses. There were two place settings: obviously an invitation to the colonel to sup with Cadoudal.

“You see, Monsieur de Montrevel,” said Cadoudal, “my men hope you will do me the honor of supping with me.”

“And it’s good they do,” answered Roland, “for I am starving, and if you didn’t invite me, I would try to take what I could by force.” The young colonel sat across from the Chouan general.

“Please excuse me for the meal I’m serving you,” said Cadoudal. “I do not receive hardship bonuses like your generals, and you have somewhat cut off my food supply by sending my poor bankers to the scaffold. I could pick a quarrel with you on that score, but I know that you used neither trickery nor lies and that everything happened loyally among soldiers. So I have nothing to complain about. And what’s more, I need to thank you for the money you managed to send to me.”

“One of the conditions Mademoiselle de Fargas set when she identified her brother’s murderers was that the sum she received was to be sent to you. We—that is, the First Consul and myself—have kept our promise, that is all.”

Cadoudal bowed slightly; with his own insistence upon loyalty, he found all that perfectly natural. Then, speaking to one of the Bretons who had borne the table, he said, “What can you give us along with this, Brise-Bleu?”

“A chicken fricassee, General.”

“That’s the menu for your meal, Monsieur de Montrevel.”

“It’s a real feast. There’s only one thing I fear.”

“What is that?”

“As long as we’re eating, things will be fine. But when we need to drink.…”

“Ah, you don’t like cider,” said Cadoudal. “Damn! This is embarrassing. Cider and water. I have to admit that my wine cellar has nothing else.”

“That is not the problem. To whose health will we be drinking?”

“So that’s what troubling you, Monsieur de Montrevel,” said Cadoudal in a dignified tone. “We shall drink to the health of our common mother, to the health of France! We serve France with different minds, but, I hope, with the same love.

“To France, good sir!” said Cadoudal, filling his glass.

“To France, General!” replied Roland, clinking his glass against the general’s.

Their consciences clear, they both sat down gaily, and with good appetites they dug into the cabbage soup. The elder of the two was not yet thirty years old.

V The Mousetrap (#ulink_2f265fb8-703c-59b7-8443-229f3a12f1a3)

A BELL WAS RINGING vibrantly, playing “Ave Maria.” Cadoudal pulled out his watch. “Eleven o’clock,” he announced.

“You know that I am at your orders,” Roland answered.

“We have an expedition to complete six leagues away. Do you need some rest?”

“Me?”

“Yes. If so, you may sleep for an hour.”

“Thanks, but that is unnecessary.”

“In that case,” said Cadoudal, “we shall leave when you are ready.”

“And your men?”

“Oh, my men! My men are ready.”

“Where?”

“Everywhere.”

“I’ll be damned. I’d like to see them!”

“You’ll see them.”

“But when?”

“Whenever you want. My men are quite discreet. They show themselves only when I give the signal.”

“So that if I wanted to see them.…”

“You have only to tell me; I shall give the signal and they will appear.”

Roland began to laugh. “Do you doubt it?” asked Cadoudal.

“Not in the slightest. Only… Let’s go, General.”

“Let’s go.”

The two young men wrapped themselves in their coats and stepped outside.

“Let’s get on our horses,” said Cadoudal.

“Which horse shall I take?” asked Roland.

“I thought you would be pleased to find your own horse well rested, so I chose two of my horses for our expedition. Take your pick. They are both equally good, and each has in its saddle holsters a pair of English-made pistols.”

“Already loaded?” Roland asked.

“And loaded with great care, Colonel. That’s a job I never entrust to anyone else.”

“Well, then, let’s mount,” said Roland.

Cadoudal and his companion climbed up onto their saddles and started down the road toward Vannes. Cadoudal rode beside Roland, while Branche-d’Or, the major general of Cadoudal’s army, rode twenty paces behind them.

As for the army itself, it remained invisible. The road, so straight it seemed to have been drawn by a tight rope, appeared to be totally deserted.

When they had ridden approximately a half league, Roland grew impatient: “Where in the devil are your men?”

“My men? … On our right, on our left, in front of us, behind us; everywhere.”

“That’s a good one,” said Roland.

“I’m not joking, Colonel. Do you think me so imprudent as to venture out without scouts in the midst of men so experienced and vigilant as your Republicans?”

Roland kept silent for a moment; and then, with a doubtful gesture, he said, “You told me, General, that if I wished to see your men, all I needed to do was say so. Well, I’d like to see them now.”

“All of them or just a part?”

“How many did you say would be with you?”

“Three hundred.”

“Well, then, I’d like to see one hundred and fifty.”

“Halt!” Cadoudal ordered.

Bringing his hands to his mouth, he imitated the call first of a screech owl, then of a barn owl. For the first call, he turned to the right, and for the second, to the left. The last plaintive notes had barely died away when suddenly on both sides of the road shadowy human shapes appeared. Crossing the ditch that separated them from the road, they began lining up on both sides of the horsemen.

“Who is in command on the right?” asked Cadoudal.

“I am, General,” answered a peasant, stepping forward.

“Who are you?”

“Moustache.”

“Who is in command on the left?” Cadoudal inquired.

“I am, Chante-en-Hiver,” answered a second peasant as he stepped forward.

“How many men do you have with you, Moustache?”

“One hundred, General.”

“How many men are with you, Chante-en-Hiver?”

“Fifty, General.”

“So, are there one hundred fifty in all?” asked Cadoudal.

“Yes,” the two Breton leaders answered together.

“Does that match your figure, Colonel?” asked George with a laugh.

“You are a magician, General.”

“No, I am only a poor Chouan, just another unfortunate Breton. I command a troop in which each brain knows what it’s doing and in which each heart beats for the two great principles of this world: religion and royalty.” Then, turning toward his men: “Who is commanding the vanguard?” he asked.

“Fend-l’Air,” the two Chouans answered.

“And the rear guard?”

“La Giberne.”

“So we can safely continue on?” Cadoudal asked the two Chouans.

“As if you were going to mass in your village church,” Fend-l’Air answered.

“Let’s continue on, then,” Cadoudal said to Roland. And turning back to his troops, he said: “Now scatter, my good men!”

In an instant, every man had leaped across the ditch and disappeared. For a few seconds, the horsemen could hear branches rustling and a trace of footsteps in the underbrush. Then nothing at all.

“Well,” said Cadoudal. “Do you believe that with such men I have anything to fear from your Blues, however brave and skillful they might be?”

Roland sighed. He agreed totally with Cadoudal.

They continued riding.

About one league from La Trinité, they saw on the road a dark mass that kept getting larger. Suddenly it stopped.

“What’s that?” asked Roland.

“A man,” said Cadoudal.

“I can see that,” Roland answered. “But who is it?”