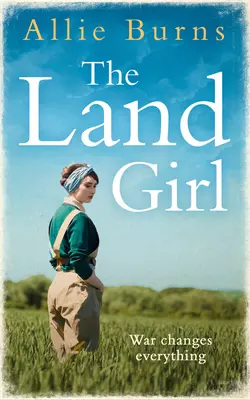

The Land Girl: An unforgettable historical novel of love and hope

Allie Burns

War changes everything…Emily has always lived a life of privilege. That is until the drums of World War One came beating. Her family may be dramatically affected but it also offers her the freedom that she craves. Away from the tight control of her mother she grabs every opportunity that the war is giving to women like her, including love.Working as a land girl Emily finds a new lease of life but when the war is over, and life returns to normal, she has to learn what to give up and what she must fight for.Will life ever be the same again?What readers are saying about THE LAND GIRL:‘A fabulously written historical novel set during the First World War that is absolutely impossible to put down, The Land Girl is another exceptionally told tale by Allie Burns.’‘5 Words: Family, responsibility, love, grief, belief.’‘I can’t recommend this book enough.’‘The Land Girl is an absorbing, compelling and evocative historical novel I simply couldn’t bear to put down.’‘Elegantly written, wonderfully poignant and wholly mesmerizing, The Land Girl is an atmospheric and unforgettable tale of love, war, hope, second chances and healing that will hold readers in thrall from beginning to end.’‘This book was honestly such a delight to read’‘A great story very compelling … definitely recommend’Praise for The Lido Girls:'Is immediately on my "best books of 2017" list’ Rachel Burton, author of The Many Colours of Us‘A beautifully-drawn cast of characters blended with meticulous research, so evocative of the era, pull you into a heartwarming page turner’ Sue Wilsher, author of When My Ship Comes In

The Land Girl

ALISON BURNSIDE

HQ

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2018

Copyright © Allie Burns 2018

Allie Burns asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

E-book Edition © July 2018 ISBN: 9780008262730

Version: 2018-06-27

Table of Contents

Cover (#uce1180bf-288d-509e-9de7-e128585e4360)

Title Page (#uf52c19f0-b258-5130-9d61-42fc32f5ae3a)

Copyright (#u2a0e7320-b72b-5437-a3fe-9fdfca39bc7f)

Dedication (#u7e094936-77d0-50ee-a399-3c10642b575f)

Chapter One (#u0efd93de-ce8d-5220-a8e2-033b51688260)

Chapter Two (#ue34d03f0-0972-5fd4-a6fb-ed6ae408b808)

Chapter Three (#u47becac1-6cc2-56e8-9f3f-fc43e387f421)

Chapter Four (#u63d1dc5c-a964-5c08-ad88-bdb224a70d73)

Chapter Five (#uaf57d00b-58f6-51f2-91a5-b34da5a4e1a7)

Chapter Six (#u183e6351-54db-5d03-8aa9-6f5aa3a98e60)

Chapter Seven (#u506bf356-79a1-5635-9545-60b457f7fb09)

Chapter Eight (#u809d1b88-a823-5739-a027-edc8de922f14)

Chapter Nine (#u8eb77e6f-7494-5964-a69b-04fde203e16e)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Historical Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Allie Burns (#litres_trial_promo)

Read on for a Sneak Peek of The Lido Girls … (#litres_trial_promo)

Dear Reader Letter (#litres_trial_promo)

Dear Reader Letter (#litres_trial_promo)

Endpages (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

For Dylan and Evie

Chapter One (#u0751940b-f65d-518d-9b26-841020ac8204)

March 1915

Emily held her breath as she stood at the top of the stairs. When she was sure it was safe she tiptoed down, which was not that easy in her brother John’s work boots, even with the gap in the toes stuffed with balled-up newspaper.

The muffled chatter from her mother’s knitting party flooded the hallway. She quickened her pace to reach the safety of the door that led through to the kitchen, only to narrowly avoid colliding with Daisy – the housemaid – and a platter of crustless sandwiches. They greeted one another and before Emily could remind her, Daisy nodded and said, ‘Don’t worry, I haven’t seen you.’

Emily opened the back door and the dazzling sunlight caressed her skin. She would have to make it up to Mother later because she couldn’t sit in that stifling sitting room, knitting socks for the soldiers at the Front when the sun shone.

‘By the way,’ Emily called back to Daisy who was straightening out the sandwiches again. ‘Did you leave this on my pillow?’ She waved a newspaper cutting that she’d found on her bed in an envelope addressed to her.

Daisy shook her head. ‘I found it on the doormat, hand delivered.’

Emily shrugged. She would thank whoever the sender was when they made themselves known.

Outside, she leant back against the scullery door, and admired the plump, carefree clouds, shifting their shapes and rushing onwards against the backdrop of the heavenly blue sky.

She held up the notice cut from the Standard, reading it slower this time to take it in. Her heart began to thump.

Women on the Land

Highly trained women of good birth and some country-bred women, hitherto working in service, or in trade, will make themselves useful in any way on a farm to gain experience.

May we make known that we wish to hear from farmers, market gardeners and others wanting the services of women for work on the land.

The notice went on to say that educated girls would act as a shining example to village and city girls – encourage them out in their numbers to do their bit for the war effort.

But whoever posted this through the door must know that she wasn’t ‘highly trained’ in anything other than English literature, and that wasn’t an easy situation to fix. She did spend far more time on the farm and outdoors than was usual for a girl like her, as Mother was always reminding her, but that didn’t mean she could turn her hand to farming so easily; she’d need to be trained and the notice in the Standard said that took six weeks.

She couldn’t in all good conscience leave her Mother to attend a course. Mother hardly slept and was afraid to be left alone since Father had died two years ago, and it was even worse now Emily’s older brother, John, had received his officer commission, turning Mother a ghastly pale whenever the delivery boy came up the path.

At the tool shed, she lifted Mr Flitwick’s hoe and carried it back to the kitchen garden – humming to herself while she worked. She tilled three neat rows width-ways in the fine, crumbly soil of the raised bed. Mr Flitwick, their gardener, had generously given the bed over to her and her experiments, along with access to his stash of seeds. She came out here when Mother thought she was resting, reading or writing letters. It was a secret between her and the few trusted staff, and her little winged friends. She scattered the black dots, buried and then sprinkled them with water from the can.

‘Hello there,’ she said to her usual companion, a robin, who watched her from his favourite spot on the espaliered pear tree that spread its arms out along the wall. ‘I see what you see.’ She lightly pinched the flailing worm that she’d exposed with her hoeing, scooped a hole with the bare fingers of her other hand and tucked the worm inside, blanketing him with the soft soil. ‘I’m afraid you’ll have to find your own afternoon tea,’ she told the robin. ‘My crops need this one.’

The bird whistled back at her, probably an admonishment for not doing as she was bid.

Emily started as Edna, the cook-general, opened the door.

‘The mistress is asking where you are,’ Edna said. ‘She was expecting you to join her and her guests.’

Emily contemplated her boots – John’s boots – her mud-lined fingernails, the hem of her skirts that had been steeped in the soil and were now a sepia brown. She would usually dash upstairs, clean, change her clothes and be back down in the sitting room knitting, awaiting Mother’s approving nod. But the newspaper article had fired her up, given her dreams a shape, and now she simply couldn’t bear to be parked on a sofa cushion while the conversation drifted around like pregnant rain clouds.

‘Could you say I have a headache? It’s a lot to ask, but I’d let her down if I went in there today.’

And if it was anything but knitting … Mother’s stitches were always perfect and uniform; Emily’s always too large and loose. ‘The men will have cold feet wearing those,’ Mother would say. Always pointing to the spot where Emily had dropped a stitch. And as for the yarn, it went on forever; no matter how many hole-filled pairs of socks she made, no matter how many stitches she dropped, or how unevenly they grew, the yarn kept on coming.

As she wiped her brow with her sleeve the sun came out from behind a cloud, rooting her to the spot. She sighed. How on earth would she ever persuade Mother? When Father was alive he’d wanted nothing more than for the HopBine Estate and its four-hundred-acre farm to be the epicentre of village life. He’d dreamt of the family living the rural idyll that he’d moved them out of London to enjoy.

She’d asked once, when Father was alive, if she could take a course at a horticultural college. Lots of educated women were doing it, and Mother hadn’t objected then. She’d even believed it would be good for Emily to follow her dreams. Now, Mother’s frown made her shrink inside. Things had changed. A good marriage and being a dutiful daughter – those were the things Mother wanted from her now.

The gate out of the walled kitchen garden led to the lawns. The sitting room, and Mother, overlooked those very same lawns. So, Emily cut around to the front of the house and then raced across the gravel drive, and through the gap in the hedge before the cedar avenue that took her into the paddock that joined HopBine House to its farm. The paddock usually housed Mother’s stallion Hawk. The other horses had been requisitioned, but Hawk was old and Mother’s dearest companion – though she’d not ridden him since Father had his heart attack.

Today, however, the field had a different guest. She placed her boots carefully now, as if she were sneaking down the hallway again, to keep a safe distance from Lily, a tetchy heifer. Lily had lost her first calf by trampling it, possibly an accident – Mr Tipton the farm’s manager wasn’t sure – so the cow was being given a second chance and being grafted with a spare twin. Mr Tipton was pleased with how it had gone so far. The new calf had nursed from Lily last night, although Lily had been unsettled and hence she and the calf had been separated from the rest of the herd.

Lily snorted at Emily now, warning her to keep her distance. Emily didn’t need to be told twice.

A third of the way down the paddock, she snuck inside the foliage of a low-growing Turkey oak. Its web of trunks close to the ground offered low-hanging, gnarly, twisted arms; the perennial leaves offered a canopy, while the other trees were just warming up for spring. The ground was dotted with scraggy grass tufts like brushes. A crow batted the air as it took off.

She climbed, weaving her way up, until she could peep through the branches to enjoy the view of the HopBine Estate. To think, she might be working by Father’s side now, but it wasn’t to be. Neither Father, nor his dreams, had survived.

With another sigh, she took in the view of the church tower and Perseverance Place in the dip. Father had built the labourers’ cottages there shortly after HopBine House was finished. Beyond them was the crumbling old paper mill down by the orchards next to the stream, and then the villas belonging to the new countrymen, which lit up a previously darkened village enclave, then Hangman’s Wood and fields all the way to the coast. There the submarine-infested channel lay, and on the other side of that, France and Belgium being torn apart by the war.

Right in front of her, at the bottom of the enclosure was the farmyard, where the chickens bustled about, clucking. Behind the yard were orchards full of apple, cherry and cob trees, hop gardens and other meadows for the sheep and cows.

Two women she recognised from the village caught her attention. Olive Hughes the wheelwright’s wife and Ada Little the blacksmith’s wife hurried over a stile to the right of her. Lily’s new calf was on its own at the farmyard boundary, while Lily herself was higher up the paddock. The cow stamped a warning hoof at Olive and Ada who were now a wedge between the mother and her adopted baby.

The two women were in such a rush that they hadn’t even noticed. What on earth were they thinking, getting in between a cow and her calf?

‘Watch out!’ Emily called from the tree, causing Olive to start and let out a yelp. Lily turned her head, looking directly at the village women. ‘Mad cow on the loose!’ The cow snorted. Ada screamed. She tried to smother it with her hand, but it was too late – she had startled Lily.

The cow was slow away, heavy and lolloping, but within a few strides it was clear she was picking up pace. She was running down the hill, her head high as she charged down, homing in on her targets.

Emily dropped from the tree with a thud. ‘Stand your ground,’ she called to the women. Ada took no notice, turned on her heels and ran like the clappers back towards the stile. Olive, meanwhile, remained rooted to the spot, mouth agape, whimpering.

Lily dropped her chin to her chest, took a deep breath and sprinted. Olive would be trampled if Emily didn’t do something. Lily was fast, her size deceptive. Emily’s boots thumped down the paddock. She bent to pick up a stick, didn’t drop her pace, and then she reached Olive and stood between her and Lily, facing the cow down.

‘She’s going to flatten us!’ Olive cried.

‘Run like stink,’ Emily yelled, her breath coming thick and fast. ‘Don’t look back and don’t stop until you’re over the stile.’ Olive hesitated, her eyes darted back and forth, torn between saving her own skin and leaving Emily there. But there wasn’t time to think it through – Emily pushed her away. ‘Go!’ she cried.

As the footsteps and the whimpering receded, it was just the two of them: Emily and Lily. Emily spread her feet wide, waved the stick at the cow, stretching out her other arm to make herself as large as possible.

‘Now, girl,’ she shouted, her heart pounding as violently as Lily’s hooves. The thud, thud grew louder; the ground even shook.

Behind her came a scream that carried through the air. Emily ignored the hysterics, and kept on waving the stick.

‘Look, you daft beast, the calf is safe. It’s just me. You know me. We’ll both die if you don’t stop.’

She stared into Lily’s eyes, willed them to have a better sight than the cow had been born with, that Lily might recognise Emily before it was too late. The beast was a matter of feet away now, thundering closer. She glanced at the stile; she should have run with Olive, she wouldn’t make it in time now. She waved the stick, close enough now to make out her spidery eyelashes. She held her other hand aloft and expelled a deep guttural yell that echoed and reverberated through her whole body, making her shake, waiting, waiting for the impact, and to be biffed by Lily’s head from here to next Thursday.

As Lily’s nuzzle reached Emily’s palm, the cow stopped, dead. Emily relaxed her hand and patted the cow’s nose as Lily panted. So did Emily, her heart boom, booming in her ears. Lily nudged Emily’s hand out of the way, her round gelatinous eyes close to Emily’s, then her fleshy tongue dragged itself across her face. Emily giggled.

‘That tickles, Lily,’ she said, scratching playfully at the sparse fur above the cow’s nose. Lily mooed in appreciation.

‘It’s wonderful to see you look after your new calf, Lily,’ she said, backing away now, but still facing the cow. Still holding the stick aloft, she took careful, steady strides back, and back, until finally she gripped the solid surface of the stile, and hopped to safety.

Emily took a deep breath; her heart was just about settling down now.

‘Well, that was close.’ She leant over the stile to catch her breath. Lily had forgotten all about her charge already, she glanced over at the innocent calf and chewed her cud, watching them with a disinterested gaze. ‘Are you both all right?’ she asked the women.

Both of them had been struck dumb by the whole event.

‘Th-thank you, Miss Cotham,’ Olive Hughes said in the end, and Ada then found her voice too.

‘How did you do that? How could you be sure that the cow would stop?’

‘I couldn’t,’ Emily confessed. ‘Be careful next time. If she can trample her own calf to death, she won’t think twice about flattening you.’

Just as she was about to find out what the women had been running from in the first place, dear old Mr Tipton waddled around the edge of the paddock, waving his finger at the women and shouting something that Emily couldn’t quite make out.

The two women gawped at one another, thanked Emily again and shot off in the opposite direction to Mr Tipton.

Emily waited, trying to hide her amusement from Mr Tipton at his pink-faced exertion. When he caught her up he tipped his brown felt hat. But as Olive Hughes and Ada Little disappeared over the horizon he put his hands on his hips and kicked a clod of soil with his crusty old boots.

‘Whatever is going on, Mr Tipton?’ she asked him.

‘Those two are skiving off again.’

‘Mrs Hughes and Mrs Little?’ she asked, confused as to what they might be skipping.

‘Aye. Those two are what the Board of Trade calls help. I’m supposed to have the same yields from the farm even though my men are all gone, and in their place, they’ve sent me two village women who run off whenever my back’s turned.’

‘You need a supervisor for your new workers, Mr Tipton,’ she said.

‘Women,’ Mr Tipton said with a shake of his head, as if he hadn’t heard her. ‘No disrespect to you, Miss Cotham, but we’re never going to win this war if we have to rely on the likes of those two. The government’s lost leave of its senses if it thinks it’s so.’ He put his hands together in a prayer. ‘Please Lord, don’t send me any more of your women,’ he said, face upturned to the heavens, before he trudged back to the farm.

That was another thing the person who sent her the newspaper notice didn’t realise. She could be as highly trained as any man, but Mr Tipton would never view her as anything other than the owner’s daughter.

Chapter Two (#u0751940b-f65d-518d-9b26-841020ac8204)

April 1915

She marched across the lawn on her way back from the farm. She’d start with Mother, simply show her the newspaper notice from the Standard and explain how she needed to take the training so that she could help Mr Tipton keep the women in order. They owned the farm, and as the family depended on its profits she might just see it as a solution. It was wildly optimistic. Her pace slowed as she pictured Mother frowning as she read the article.

Once she reached the terrace her courage began to fail her. Mother’s knitting-party guests stood at the floor-length sitting room windows. There were two smaller figures – her mother one of them, the other most probably Norah Peters, the village solicitor’s wife. And there was a woman with a stout gait, which must belong to Lady Radford from Finch Hall. Members of the titled upper class like the Radfords and the industrial middle class like the Cothams mingled frequently in the countryside, which was a shame because Lady Radford was at their house far too often and always telling Mother how to think.

At the French door, Emily muttered, oh dear. The stout hips weren’t Lady Radford’s at all. Neither was Norah Peters standing beside Mother. Instead, a clean-shaven, smart young man in a suit, and an older woman, wearing one of the widest brimmed and heavily feathered hats Emily had ever seen, waited with smiles on their faces. Mother glared at her daughter’s muddy and torn skirts and her brother’s large work boots protruding from beneath her soggy hem.

She remembered then: it hadn’t been a knitting party at all. It was afternoon tea with Mother’s friend’s son. It was another of the faceless young men from good families that Mother kept inviting for her to meet – someone who might take care of the both of them. His family were something in construction, middle-class industrialists like them, but he was in banking. Would this one be any more interesting than the others? They were always a little cold, and distant, superior even, and their favourite subject was usually themselves.

‘Goodness me, Emily!’ Mother exclaimed, as she opened the door, blocking Emily’s path. ‘Your head is much better then?’ Behind her, Daisy bit her lip and pretended to focus on replenishing the teacups. Emily pulled an errant leaf from her hair and straightened her skirt.

‘I always said that the expression “being dragged through a hedge backwards” was custom-made for you.’ Mother’s voice was false, raised with an edge to it that kept up appearances whilst telling Emily she’d be in for it later.

‘Use the back entrance, dear,’ Mother said with a steel and tightness in her tone that only Emily could detect. ‘Smarten up and then you may join us.’

Emily tried to smooth some of her hair back into its chignon, but so much had fallen loose it was hopeless; just like her. What had she been thinking, running off to the farm like that? No wonder Mother was never satisfied with her.

In her bedroom, she made an extra effort to smarten up. She put on a hideously frilly dress that Mother liked best, shook her hair loose and tugged the brush through it again and again until it had the sheen of a sweet chestnut. Then she backcombed and pulled her locks over a pad to create a respectable, curved pompadour. For the finishing touch, she lifted a fuchsia-coloured camellia bloom from the vase on her dresser and tucked it behind her ear.

Downstairs, the man, whose name she couldn’t remember despite Mother having talked about him all week, had left the women to talk and was on the terrace admiring the view.

‘Lovely day,’ he said, as she approached him. He was quite handsome, she supposed. It was his nose that spoiled him; it was too big for the rest of his face, though his ears were in proportion with the nose, which was something.

‘Oh, it really is,’ Emily said.

He stood so at ease with his hands in his trouser pockets that HopBine could have been his own home. He seemed quite comfortable with the silence. Then he pointed up to the roof.

‘You’ve some tiles missing, and the guttering is in a bad way.’

‘Thank you,’ she said, sneering at him as he turned away. ‘We’re aware the house needs some repairs. My brother is away at the Front at present, so our priorities have changed. You work in banking, I understand,’ she said. ‘Is that interesting? A challenge?’ She was talking too fast. It happened when Mother was watching her. The pauses between words evaporated making them all slide together into a chaotic jumble. ‘I can’t say I know much about money, or investments.’ Her mouth really was running away from her. She should be quiet, adopt some of his detached, confident demeanour.

She checked over her shoulder. The women were talking, but Mother’s gaze was resolutely on her daughter. She gestured for Emily to remove the bloom from behind her ear.

‘No, I don’t suppose you do,’ he said, not without a hint of superiority. ‘It takes a certain level of skill and education to master the markets.’

Her back straightened at his condescension. She twirled the camellia between her thumb and forefinger, before lifting her head and capturing him in her gaze. ‘I’ve always regarded the world of finance to be a little soulless. And you are helping to confirm my theory that people who enjoy the company of numbers are insentient beings themselves.’

‘Oh, …’ he said, breaking eye contact. ‘Well, let me assure you that isn’t the case at all.’

‘No? Perhaps your remarks don’t represent you well.’

He concentrated on the horizon, but she continued to study him fixedly, let him bathe in the discomfort. He found something of interest on the concrete floor of the terrace. His hair flopped forwards to obscure his oversized nose. She paused a while longer, let the silence hang between them and then checked the window. Mother’s gaze was still trained on her; probably trying to read her daughter’s lips. She shouldn’t be picking arguments.

‘Do you play tennis often?’ She dropped the pink bloom to the ground, slipping into the polite patter expected in these circumstances. But the chap was frowning, he hadn’t liked being told off by a young woman.

He told her he didn’t, no, he was training to fight a war, and then he excused himself and slipped back in to the safety of the older women’s conversation, slamming the French door harder than was necessary, and trampling on the camellia’s petals. She hesitated before following him in. Mother’s expression was granite-edged. There was nothing she could do about it but limit the damage, which for now meant she would keep her newspaper clipping to herself.

*

When she found Mother in the sitting room after the guests had gone later that evening, she caught her reading a letter, a smile on her face. As Emily crossed the threshold, Mother hastily balled the letter up, stuffed it in her pocket and lifted the knitting from her lap.

‘You didn’t mention that you’d had some post,’ she said wondering which brother it might be from. ‘Cecil or John?’

‘What?’ Mother’s cheeks coloured. ‘No, no, neither.’

It should have been cosy in the sitting room. Daisy had cleverly used their scant coal supplies to time the fire to perfection for the early evening, but there was a persistent chill in Emily’s spine.

‘I caught two of Mr Tipton’s volunteers in trouble on the farm earlier on,’ Emily said before Mother could mention the mess she’d made of the house call. Lawrence, as it turned out he was called, had shown no interest in wanting to hear from her again. No one would ever ask her what she thought about him. It didn’t matter. All that mattered was the impression she made, while the men could be as rude as they liked.

‘If I hadn’t been there to rescue them, Mrs Hughes and Mrs Little might have been trampled to death by Lily,’ she continued.

‘I wonder …’ Mother said looking up.

‘Yes?’

‘If Cecil might be able to come home from Oxford when John is next on leave. Wouldn’t it be nice to have the boys back together?’

‘I suppose it would, yes,’ she replied. ‘We could have a Christmas celebration for John – he’d like that, to mark the one he missed.’ It would be wonderful to see John again, he always listened when she told him about her adventures on the farm.

‘Good idea,’ Mother said. Emily paused for a moment to savour the rare praise. She smiled. Mother’s eyes glistened, a sure sign she was thinking up ideas of what they could do for John on his next leave. Perhaps this was her moment. She took a deep breath, rummaged inside her pocket for the newspaper article. Just as she was lifting it out, Mother changed the subject.

‘Despite what happened today, all is not lost. I told Lawrence’s mother that you’d write to him when he gets his first commission.’

‘Would Lawrence like that?’ Emily asked. He’d hardly said another word to her once he’d been back inside the sitting room.

‘Why ever not?’ Mother smiled to herself as she began a new row. Emily’s stomach tightened; Mother mustn’t have false hope. Lawrence had probably already forgotten about her, and she would gladly forget about him.

She may as well get it out of the way. She reached inside her pocket and handed Mother the article, flattening it out for her. Mother reluctantly gave up her knitting, held the piece of paper to the lamplight.

‘I suppose if they train up these educated girls they’ll soon bring the likes of Olive Hughes and Ada Little under control.’

‘Exactly.’ So, Mother had been listening to her after all, but Mother handed her back the piece of paper and resumed her knitting. She hadn’t understood the relevance of Emily handing her the announcement.

‘The thing is, Mother, I wonder, could it be me? I love the outdoors and—’

‘You?’ Mother said. ‘Do you mean go off on a training course? And how much will that cost? We’re already paying for your brother’s officer commission; his mess fees won’t pay themselves.’

‘They would pay me,’ she said.

Mother pinched her nose. ‘I have enough to worry about with your brother away at the Front, and with conscription looming I might end up with both sons fighting.’

The reply would have been the same no matter what she’d said. Many of her old school friends had answered the call for nurses, canteen supervisors, ambulance drivers, tram conductresses, even policewomen. Lady Radford was now the commandant of the hospital she’d set up in her home, Finch Hall, the village’s big manor house. Clara Radford, the same age as Emily, was the assistant for goodness’ sake. Her ambition was humble in comparison; she only wanted to help out on their family’s estate.

‘Even if I were to work here on our own farm?’

‘Even then.’

Mother glanced up from her knitting. ‘Don’t look at me like that. It isn’t right for you, an educated girl with an Oxford Board School Certificate, to be a labourer. On land we own as well. No, no, no. Not when you’re in the market for a decent husband.’

‘Lady Clara is of higher standing than us, and she’s working,’ Emily argued. ‘I would be able to live here, and I could work part-time hours so you aren’t on your own.’

Mother tossed her knitting to her lap and raised a hand to her head. ‘What did I do to deserve such a difficult daughter? I turn a blind eye to you wallowing about in the soil in the kitchen garden. Yes, don’t think I don’t realise. Climbing trees – I see you doing that, a girl of nearly twenty, of marriageable age, up a tree in her best clothes. Tailing Mr and Mrs Tipton around, making a nuisance of yourself on the farm, when I have other, more important, things to worry about and need a daughter as a companion while she finds a husband and supports me through a difficult time.’

‘I only want to do my bit for the war.’

They knitted in silence. The war was choking her, making her life smaller. Emily dropped a stitch and in the act of trying to pick it up a second loop of wool had slid from her needle point.

Emily paused while Mother dug the tip of her needle into a new stitch. ‘Is this what you were daydreaming about when you lost your self-control and made inconsiderate and hurtful remarks to Lawrence?’ Mother said.

Emily groaned, threw the knitting needles clattering to the floor.

‘Emily Cotham,’ Mother exclaimed. ‘He is a very charming chap, who offers a prospective wife a comfortable life, perhaps with your own garden to tend. The sort of chap who takes care of his mother and would do the same for his mother-in-law. But instead you tried to belittle him.’

‘He was rude first,’ she began, but stopped herself before she made things worse. Mother was right: she had been trained to show better character than she had today. The newspaper article had fired her up, but she should have shown restraint and not retaliated. Mother was only trying to help and now she was being ungrateful.

‘I hope when you write to him you show him more interest, and gratitude for what he’s doing for the country.’

‘Of course. But would you at least agree to think about me doing some war work?’

‘We have pressing issues closer to home to tend to.’

What could be more pressing than putting food on the table, and keeping their own farm productive and running? The movement was growing. The newspaper had spoken of a land army for women; the need for girls like her was growing and she wouldn’t give up.

‘Please?’ she asked. Shouldn’t her mother be proud of her?

‘Oh dear, your whining is giving me a migraine. I think you overestimate the extent of what you might do. You’re not very strong – there’s nothing of you and no one will take you seriously if you’re smaller than them. Mr Tipton will laugh you off the land.’ Mother’s withering look and cutting words made her head bow. She couldn’t bring herself to say another thing in response to that.

Emily picked up the heel stitches with her needle, a task that could make her distracted by something as benign as the ticking clock, but worse still, she inspected the whole sock; she’d made a mistake when casting off the toes. She couldn’t go back and correct it now. She toyed with the idea of throwing the knitting onto the fire and letting it burn. She grabbed the newspaper cutting, folded it back in her pocket and clomped up the stairs. Mother didn’t even look up or show that she’d noticed Emily’s display of frustration.

In her room, she stopped herself from slamming the door shut. Mother always reduced her to a child, and each time she reciprocated with childish behaviour. She must learn to not yearn for her Mother’s approval or affections because it was futile of her to hope for them. She couldn’t help herself and slammed the door shut anyway, not caring if she was nearly twenty. If she was going to be treated like a child, why not behave like one?

She slid down the wall and sat with her back to the bedroom door and flicked through the newspaper.

Corporal Williams, fighting for King and country in Flanders, seeks a well-bred country lady for correspondence and conversation and tales from our green and pleasant land.

Well, Corporal Williams. She’d be delighted to write and tell him all about this pleasant land, and it would be jolly nice to correspond with someone who was interested in what she had to say.

Chapter Three (#u0751940b-f65d-518d-9b26-841020ac8204)

Dearest Emily,

I am so pleased that you decided to write to me. You are quite right that we are in need of good cheer from home. I miss Yorkshire, and the dales more than I can put into words.

Thank you for telling me all about HopBine Estate – it is clear that the place is very dear to you.

I can’t say too much because of the censor, but I can tell you that we’re stationed up the line, billeted in a barn at the moment. There are no boards so we sleep on the ground, and with no fire it is terribly cold at night.

I admire your desire to work; don’t give up on it.

Fondest wishes

Theo Williams

She didn’t have to wait long in the evening for Mother to retire to bed. Once the light had disappeared from beneath her bedroom door, Emily crept down the hallway and out through the back door.

There was no moon and a chilly breeze blew across the open fields and straight down her neck. She couldn’t go back for a lantern in case she disturbed Mother.

At the edge of the driveway, she stopped to admire her home; cream coloured, and square, it glowed a little in the shade of darkness. It had three pitched gables. Her late father had designed and built the house when he’d moved the family to the country to set up the cement works. Father had built one gable for each of his children. Those gables sheltered each of their bedrooms and protected them from the rain and wind. But the missing tiles and loose guttering that Lawrence had noticed made their situation now an open secret.

She entered the cedar avenue that lined the long drive down to New Lane and then it was a short walk to the farmhouse. All of the lights were hidden behind curtains and blinds and pulled tight in case of a night-time visit from a Zepp. Even the candles on the makeshift shrine at the edge of the village green had been extinguished.

But it didn’t matter, she could find the way in the deepest of dark nights.

In the low-ceilinged farmhouse kitchen, she found Mr Tipton stroking Tiger, the tomcat, on his lap. The farm manager was halfway through a story to Mrs Tipton.

‘Oh do go on,’ Emily urged him, presenting Mrs Tipton with some bluebells that she’d picked in Hangman’s Wood earlier that morning. ‘You know how I love your stories.’ He had a wonderful imagination and his improvised tales of the forest folk had kept Emily entertained for nearly two decades.

‘I love the scent of these beauties,’ said Mrs Tipton, bending her head into the blooms. Grey tufts escaped from her hair like Old Man’s Beard. ‘I can’t remember the last time the ole man gave me flowers. He was a romantic when we were first courting. Wasn’t you, dear? Always bringing me a posy.’

Mr Tipton shook his head and muttered something to Tiger, while Mrs Tipton shook the rafters with an almighty sneeze.

Mr Tipton found his place in his story as Emily took the armchair closer to the fire. Sally the collie dog joined her, rested her head on Emily’s feet. The warm weight comforted her toes, as the heat of the flames rose and fell against Mr Tipton’s cheeks and stroked the back of her neck.

When he’d finished the story, the conversation moved on to bemoan his dwindling workforce. He’d taken on local schoolboys and a few labourers who’d not yet joined in with the war, but more and more men disappeared every week. Some had volunteered to do their bit, a patriotic answer to the call of duty. John had joined up after the recruitment drive marched through the village. It had encouraged many of the villagers to enlist with him. Then Lady Radford had run a campaign to make their village the bravest in Britain and those who hadn’t answered those calls had gone to help build the seaport at Richborough.

‘The government are setting up a corps of educated women, to act as gang leaders,’ she said, but before she could continue he’d sent Tiger scurrying from his lap. ‘Good God and heaven preserve me. Not over my dead body. If women like Olive Hughes who’s worked the harvest on this farm since she was a girl can’t hack it, how am I supposed to cope with a lady who’s never done a day’s work in her life?’

Emily stiffened. After all these years of following him around, helping and learning from him, how could he not see that she could be useful?

‘What about Mrs Hughes and Mrs Little?’ Emily said. ‘Lily would have injured them if I hadn’t been there.’

‘You took a terrible risk to help that undeserving pair. You got lucky, but don’t ever think just because a cow knows you that she won’t trample you.’

He had a point. Standing her ground like that against Lily had been perilous and she was fortunate Lily had decided to stop, but surely it had shown that she was prepared to put herself forward and be counted.

‘Women don’t belong on the farm, and I shan’t be taking on any more. I’m sorry about that. The Belgians are in need of work, kind souls they are an’ all. I’d rather take on a rotten German prisoner o’ war than any more work-shy, weak-willed women. No offence.’

‘Well I am offended, Mr Tipton.’

He stood, snatched a lantern up from the wall and stomped off into the yard, slamming the door behind him before she could say any more. Emily rose to her feet and watched from the window as he swung his lamp across the farmyard. The shadows stretched and grew to ghoulish heights against the farmhouse and the Kentish ragstone of the stables.

Then as she stoked the fire, she noticed wet newspaper soaking in a bucket, being readied to make into bundles for the fire. Next to that, a pile of old newspapers. The Standard sitting on top. She pulled the newspaper cutting from her pocket just as Mrs Tipton emerged from the scullery, wiping her hands on her pinafore.

‘You got my hand delivery then.’ Mrs Tipton pointed her nose towards the cutting.

It had been Mrs Tipton? She knew more than anyone how much Mr Tipton and Mother would object. What was she thinking of – encouraging Emily to taste ideas and dreams that were out of her reach?

‘You shouldn’t take any notice of the ole man’s bluster. He’s ready for his retirement, that’s the problem. He wants life nice and easy; he doesn’t want the trouble the war is bringing.’

Sally the collie nudged at her with her wet nose.

‘It’s true, those villagers are a let-down to the farm, your family and the country,’ Mrs Tipton said. ‘And no one’s as surprised as me to learn that Olive Hughes is shirking off. But I think the ole man is wrong to say he won’t take on another woman, because a bright, strong girl like you who loves this place and the outdoors and is familiar with the animals is just what he needs. He just doesn’t know it yet.’

Chapter Four (#u0751940b-f65d-518d-9b26-841020ac8204)

June 1915

Dearest Emily,

I expect it is so very quiet with you in Kent. No such luck in Flanders. Fritz called on us twice in the night with his gas shells. I lay in a fitful half-sleep waiting for him to pay us another a visit.

How is your beautiful corner of Blighty? Please fill my head with more tales to take me far away from the goings-on here.

Must dash.

Fondest wishes

Theo

But neither Mr Tipton nor Mother would entertain the idea of Emily working on the farm and even Mrs Tipton’s initial enthusiasm for the idea waned. The authorities would be looking for a different sort of girl to her anyway, one with more experience and fewer family commitments.

The whole notion had set her back in the end. Mr Flitwick had taken over much of her kitchen garden work now that Mother had stopped the pretence of turning a blind eye and watched Emily even more closely so that her opportunities to attend to her herbs and vegetables grew fewer and further between.

Then summer came, and the warmth brought first Cecil, her younger brother, from his studies at Oxford, and then her older brother John, home on leave from the Front.

Cecil took up residence in the library, writing who knew what. He was always writing, or reading, or arguing the case of this and that.

For the first few days John was restless, and never in the house for long before he thought of somewhere he ought to be or something he ought to be doing.

‘Wherever is he?’ Mother asked her again and again. This time though, Emily knew where he was. Mr Tipton had lost even more men from the farm and asked for John’s help to discuss how they might fill the gaps.

‘I’ll go and tell him you want to see him,’ Emily told her mother, desperate for an excuse to leave. She found him mending the broken wain with Alfred, the farm’s oldest member of staff.

John had already cast the word out and that morning he’d recruited a couple of Belgian refugees and arranged to move them into one of the cottages at Perseverance Place.

To encourage him back up to the house, that afternoon Emily asked John to help her dig up the rose garden that sat at the edge of the terrace, so she could turn it into a vegetable garden. Mother perched in the window of the sitting room.

‘We’ve got an audience.’ John gestured as he thrust his spade into the soil beneath the roots of a stubborn rose bush that she’d not been able to dislodge herself.

Emily lifted herself up. Her breathing was heavy with exertion, her booted feet spread wide in the tilled soil to steady herself. Her skirts were tucked up in themselves and her hair had fallen out of its knot. Cecil sat beside Mother, smirking, while Mother’s mouth was gathered in a pinch, her brow furrowed.

‘I’m going to make the most of you being here to do as much outdoors as I can,’ she said. ‘She doesn’t belittle me in front of you.’

Emily joined John now to bend the rose bush into submission.

‘I’m sure she’ll get used to the idea of the Victory Garden.’

Didn’t he realise that it wasn’t the loss of the rose bushes that had upset Mother? She’d retrieved the newspaper article from her drawer to show him. He’d been the first person, beside Mrs Tipton, not to dismiss the idea.

‘Have you asked Mother?’ he’d asked.

‘I have, and Mr Tipton,’ she sighed.

‘Like that, is it?’

‘Yes, and I suppose …’

‘What?’

‘Well, I mean they’re probably right, aren’t they? What do I know about farm work really?’

‘What, you mean apart from following Mr Tipton about since you were this high?’ He held his hand beside his thigh. ‘And growing your own crops and your love of the outdoors, and your natural affinity with the animals?’ He shook his head.

‘All right, all right,’ she said. ‘But none of that means I could supervise a bunch of farm workers, not really. Mother probably is right …’

‘Would Father have built this place or opened the cement works if he’d questioned himself? You can’t give up that easily, Emily. They’ll train you, but I’ll bet you hardly need it.’

She smiled. He made it all sound so easy. It was true; she could do all the things he said, and Edna said she looked forward to her vegetables and herbs because they had the best flavour. Emily always kept quiet about her secret weapons; double digging and the manure she collected from Hawk’s stables to enrich the soil. Even Mr Flitwick said she had green fingers. But none of that meant anything if Mr Tipton and Mother wouldn’t listen, and even John’s golden charm couldn’t make light work of the situation.

*

It was Christmas in July at HopBine House. The last two days of John’s leave were a washout; the rain fell with a constant and unrelenting force, while heavy winds whistled around the house.

John said it was too frivolous to take a goose from the farm, but even without any of the trimmings, they lit the fire and hung stockings on the mantelpiece and she began to believe it really was Christmas. Especially being trapped inside the house with her mother, her grandmother – down for the night from London – and Cecil.

After lunch Emily slumped on the sofa, her hand propping up her chin while the rain lashed against the living-room window turning the view to a blurred grey.

‘Emily dear,’ Grandmother called from the other end of the sitting room. Grandmother had been in mourning since her son, Emily’s father, had passed away in 1913. Her hat was alive with twitching black feathers, and she hid behind a nose-length veil and a flowing black dress. ‘I’m in need of news of romance. Tell me. Do you have any? An attractive young girl like you, even one with that disconcerting hint of wildness, must have some young suitor in pursuit.’

‘Mr Tipton’s bullock is the only male interested in my sister.’ Cecil smirked.

‘Actually,’ Emily cut in, ‘I’m writing to an officer at the Front.’

As Emily took her seat at the piano, she noticed her mother was holding her breath, waiting. But she couldn’t meet her eye; Theo was a lowly corporal, a non-commissioned officer. If she dared to tell Mother the truth she’d say Emily was wasting her time and giving false hope to an unsuitable young man. But lowly or not, he’d been a ray of happiness, and she wouldn’t give him up easily.

‘He’s from Yorkshire, he’s very attentive and interested in me and my life,’ she said. That seemed to satisfy both Mother and Grandmother and so she stretched her fingers out across the keys.

‘Oh,’ Cecil whined. ‘Do you have to make that din?’ Deftly he turned the attention to himself. He hadn’t looked up from his book since he’d sat down. He’d even read it at the dinner table.

‘It’s a piano, Cecil,’ she retorted. ‘Not a brass band.’

‘Emily won’t play if you find it distracting,’ Mother said. ‘Emily dear, can’t you find a less invasive occupation?’ Mother’s gaze remained trained on her lap.

She sighed and slammed the lid shut. She could do no right. As it was, within a few moments Cecil had lost interest in his books and wandered out of the room in search of something new.

‘I would like to hear you play,’ said John. ‘Cecil?’ He called down the hallway. ‘Will you come back shortly for a game of charades?’

Cecil returned momentarily to poke his head around the doorway. ‘Anything for you, dear brother,’ he said.

Emily straightened her back and prepared to play. She hadn’t sat on this stool since before the war, before John had joined up, when they all came together in the evenings for piano music, song and laughter. They hadn’t done any of these things when it was really Christmastime, and John was away. It would have been wrong to carry on as usual without him. They hadn’t sung or played charades, either.

Grandmother and Mother stood beside Emily, while John leant an elbow on the body of the baby grand before them, where Father had done the same when he was alive. He warbled in a silly false tenor, his arms stretched out to accentuate his notes.

John took Mother’s hand. Emily had warmed up now, switched to a show tune, and John and Mother glided together to a foxtrot. Emily glanced up every now and then. Mother wasn’t hamming it up – she really did have style and grace. She gazed into her dance partner’s eyes with unbidden pride. Mother’s slim waist and hips meant she could pass for a woman John’s age, from behind. Her energy too. She was so often in her armchair these days it was a jolt to see her out of it and dancing and to recall how full of verve Mother had been when Father was alive, especially when she entertained.

Emily smiled to herself in the hallway later that evening. Home really was home when John was there. How did he do it? He was the glue that bound them together. It gave them the confidence and freedom to be and please themselves. To prove the point, Cecil was in his room with his books, while Mother, Grandmother and John talked in the library. On her way upstairs, she passed them, the door open a crack to reveal the light inside.

‘I don’t think you should ask him for help,’ she overheard Grandmother say. ‘Too much has passed.’

‘But what choice do we have?’ Mother said. Emily stopped and held her breath. ‘Things can’t go on as they are for much longer.’

‘I know,’ said John. ‘We’re approaching a point where we’ll have to shut HopBine House up.’

‘Or sell …’ Mother said. Emily put a hand to her mouth. Sell their home? No wonder Mother was so keen for her to marry someone from a good family; she must be hoping she’d save them.

Why hadn’t John said anything when they’d been on their own, digging up the rose garden? He’d had plenty of opportunity to tell her they had problems. Where would they go, and what would happen to the farm? Her legs lost their strength beneath her.

‘He’s offered help,’ John said. ‘I suggest we hear what he has to say.’

Emily took a light-footed step back towards the door, straining to hear whether John would reveal who this ‘he’ was.

‘What are you doing lurking about in the hallway?’

She jumped clean into the air and clubbed herself on the chin with the back of her own hand; Cecil had appeared on the stairs out of nowhere. ‘I was just getting a glass of water,’ she said loudly enough for John and Grandmother to hear her in the library, and then strode purposefully towards the kitchen.

She was about to chastise him for creeping around, but to her surprise he’d joined the others, too. She back-tracked. It must have been a family meeting and she’d not realised. As she reached the door, she caught a glimpse of John. He smiled, but just then Mother came into view, and snapped the door shut in her face.

‘Should I come in too?’ she called.

‘Take yourself off to bed, dear,’ Mother said turning the key in the lock. ‘It’s getting late.’

Chapter Five (#u0751940b-f65d-518d-9b26-841020ac8204)

July 1915

Dearest Emily,

I am moving up the queue and it will soon be my turn for leave. I ought to go to Yorkshire to see my mother, but I wonder could you meet me at King’s Cross station when I break my journey and pick up the train for Wakefield? I keep the photograph you sent me in my pocket, and look at you before I sleep – often you’re illuminated by shell light. But I long to see that determined chin for myself, your lively, mischievous eyes alight on me in person, my love.

What do you say?

Fondest wishes

Theo

‘You and John have had a lot of clandestine meetings in the library.’ She probed Cecil two days later under the shade of the monkey puzzle tree on the lawn, the brim of her sun hat low. Cecil lounged out on the other side of the trunk, reading, as usual. The soporific heat pushed her eyelids shut. ‘I waited up for you both last night but in the end I had to go to bed.’

‘We were playing chess.’ Cecil’s tone was falsely flippant. He was no more going to let her in on what was going on than Mother.

‘And who won?’ she asked.

‘I’d like to think I thrashed him, but I think he let me win.’

‘He always lets you win.’ She chuckled. ‘Has he ever beaten you or I at anything?’

Cecil reflected for a moment and then groaned. ‘All that effort to try and outwit him and all for nothing,’ he said banging his book against his thighs.

She hadn’t written back to Theo in the end. It would be difficult for her to travel to London without a chaperone. And after the conversation she’d overheard when Grandmother was visiting, it seemed she might need to a find herself an officer, not a corporal.

Her gardening journal slid from her grasp and her lap, but her hand was too heavy to move and catch the book. The buzzing of the bees and the collared dove in the canopy above all faded away …

She woke much later with a start, heavy still with sleep. A car door had slammed shut, footsteps on the gravel.

No one had mentioned that they were expecting guests.

Cecil had gone. She carried on where she had left off with her journal for the vegetable garden, planning which new crops she would plant and where. She hated afternoon tea and polite conversation with strangers, but it was nearing the end of John’s leave and there was no telling when he might next be back.

Now that the stinging heat of the sun had faded it was safe to emerge from the shade and cross the lawn to the borders she had helped Mr Flitwick to plant. Taking the secateurs from her pocket, she snipped the stems of some cosmos for Mother.

Declining Daisy’s offer of help, she placed the blooms into a vase in the kitchen and made her way through to the sitting room so she could casually drop by and determine whether the guest was someone she wanted to stay for.

‘Hello …’ She stopped on the threshold to assess the scene of John and Cecil flanking Mother, who perched on the edge of the sofa, wringing a lace handkerchief with her fingers.

A man with his back to her in the armchair by the door turned to face her. Her hand froze around the vase as she placed it on the bookcase. The man was the ghost of her father yet greyer, sterner, leaner. In a smarter, tailored suit, with neater hair. Altogether more groomed than her father, Baden.

The man held out his manicured hand to Emily.

‘I’m your Uncle Wilfred,’ he said. ‘Your father’s brother.’

‘How do you do,’ she said. Her mother and brothers’ faces were a mask of blank politeness, betraying no clue as to what she should think of this unexpected visit.

‘I’ve come to see your family to talk business.’

So, this must be what she’d overheard them talking about. Why had they excluded her from that?

‘You didn’t speak to my father for years, did you?’ she asked. John shook his head at her for being so frank. He was clearly intent on making a good impression.

‘No,’ Wilfred said. ‘Twenty-five years to be precise. And …’ he pointed a finger at her ‘… don’t forget – he didn’t speak to me either. I regret the whole business terribly.’

It’s a little late now, she wanted to say, but the anguished smile pinned to Mother’s face stopped her short. ‘We used to come to your house in London,’ she remembered, ‘without Father.’

‘A long time ago now. Cecil was just a baby the last time we visited,’ Mother said.

‘Yes. It was a shame you couldn’t come again. Well, if you wouldn’t mind excusing us …’

‘I’ll come too,’ Mother said, her hands twisting and turning again.

‘It’s fine, Mother. Leave it to us,’ John said.

Cecil ambled out of the room and down the hallway whistling to himself.

‘What have I said to you about wearing those boots indoors!’ Mother snapped once the men were out of earshot.

Mother stared at her hands while the conversation took place on the other side of the wall. After a while, Emily realised Mother’s hands were trembling and that she was trying to still them. Within ten minutes voices rose in the room next door. Mother joined them then, and then Cecil, and the conversation continued for a while longer. Emily hovered outside the door, hoping to overhear something, but the voices were quiet.

She sat in her bedroom, the door open. She would demand to be told what was going on. It was ridiculous to exclude her in this way as if she was nothing more than a child.

Voices, sharper now they were out of the library, travelled up from the hallway. She scampered down the stairs, but before she could join the others on the front step, Wilfred’s car was already approaching the cedar avenue.

Mother marched straight back into the sitting room and poured herself a brandy, which she swallowed down in one.

‘Whatever is going on?’ Emily asked. ‘Is he giving us money?’

Mother set her glass back down on the table as if Emily hadn’t spoken.

‘Mother.’ John appeared in the doorway. ‘We need to talk.’

‘Of course,’ Mother said. She followed John into the library, leaving her once again on the wrong side of the door.

Chapter Six (#ulink_0d4e55d4-10b5-58ed-a729-e37c088f2df3)

July 1915

Dearest Emily,

They have delayed my leave – they can’t spare us. I’ve been promised it should be next week now if I am fortunate enough to escape, or there is a shell with my name on it heading my way first.

I can’t pretend I’m not disappointed that I won’t see you at King’s Cross. Your letters have been the only good thing to come my way since I’ve been here, but I understand the reason why. I’ll linger outside the Telegraph Office just in case you change your mind and can meet me there.

Try not to be too hard on your mother – I’m sure she’s being truthful when she tells you that she thinks it’s for the best if you don’t work, even though you may disagree.

Yours

Theo

The chickens scattered to escape the sizeable boots of Mrs Tipton as she stepped out of the farmhouse door and grabbed John by the shoulders. She pulled him close, thumping the air out of him by patting his back with the palm of her hand, even though she’d only seen him the day before. ‘Ah, what a sight to see the three of you together again at the farmhouse. In you all come now,’ she said as she tugged John over the threshold.

Mrs Tipton poured them each a tea. ‘I’ve been working on him,’ she said.

Emily’s back straightened. It was the first time Mrs Tipton had mentioned the idea of Emily helping on the farm in weeks. ‘The more those women run circles around him, the more his resolve is weakening. Sometimes with men you just have to wear them down – it’s the only way.’

Before their tea had cooled enough to drink, Mr Tipton crashed into the kitchen shouting. Mrs Tipton raised her eyebrows at Emily.

‘Blasted women, blasted women!’

‘Whatever’s happened, dear?’ Mrs Tipton slid a cup of tea in front of him.

‘I thought those cows were temperamental.’ He threw his brown felt hat across the room. ‘Those beasts have nothing on women. I should never ha’ taken them on. They’re either jawing …’ he mimicked a busy mouth snapping up and down with his four fingers against his thumb ‘… or booing …’ he mimed rubbing his eyes with his fists.

‘You upset one o’ them again, have you?’ Mrs Tipton asked, tight-lipped.

‘S’not hard, it really isn’t,’ he said, kicking the table leg with his boot. ‘Another one, Annie, I think she called herself, has just packed her bags. They’re strong enough to lug their cases to the station when it means they can get out of here. You noticed that too, have you?’

Mrs Tipton nodded in reply. ‘What you need is a ganger,’ Mrs Tipton said with a wink to Emily. ‘And look who the wind has blown in for us, eh?’ She gestured with raised eyebrows towards Emily.

Mr Tipton furrowed his brow. ‘No disrespect, but what I need is more men. Cecil, you’re home for the summer. Couldn’t you help us out a bit, lad?’

Cecil’s gaze shifted about in the uncomfortable silence that followed. Cecil? Mr Tipton couldn’t be that desperate for help, surely to goodness. John caught Emily’s eye behind Cecil’s back; despite her disappointment at being overlooked again, it was too much to imagine Cecil milking cows and they both crumbled into laughter.

‘What?’ Cecil straightened his back, and his tie. ‘I think I’d command respect rather well amongst the workers.’

‘A good farmer leads from the front,’ Emily told him, clutching her stomach and grinning. After the drama up at the house, and John’s looming departure for the Front, the laughter warmed her insides.

‘It’s not that ludicrous a prospect, surely?’ Cecil asked.

John and Emily nodded at one another and said in unison: ‘Oh, it is.’

‘I really don’t see what’s so funny.’ Cecil frowned.

‘Oh, come on, Cecil,’ John said. ‘Can you really see yourself muck-spreading, digging, weeding …’ Cecil’s mouth had wrinkled up. ‘My point exactly. You won’t have time to loll around with your book, or write a thesis about the land ownership of the upper classes and the plight of the serfs. Whereas Emily here worked alongside me on the vegetable garden and I was tired and ready for a rest long before her.’

‘Exactly,’ Mrs Tipton agreed.

‘I’d like to try,’ Emily said. ‘Perhaps a trial?’

‘I appreciate you wanting to help,’ Mr Tipton said. ‘And you know I’ve always enjoyed having you around the place and you have a better understanding of the land than most, but I’ve had so much trouble. I don’t want any more. I can’t even risk you, Miss Cotham.’

‘It is her farm,’ Mrs Tipton reminded him. ‘She has every right to take good care of her family’s assets.’

She had been bending her husband’s ear for months now, and he was beginning to cave in.

‘Won’t you give me a chance to prove myself?’ Emily pressed on. ‘If you’d like, I can sign up with the government’s scheme and get some training.’

‘But she won’t need it,’ John added. ‘She knows these fields and this farm well enough. She’s watched you since she was a girl.’

‘And I can supervise the girls – you won’t need to bother yourself with chasing them about.’ It would be wonderful if that was true. Just as John had said, she mustn’t listen to the naysayers. She had to believe in herself; that was half the battle.

‘This war isn’t going to be won any time soon,’ said Mrs Tipton. ‘You’ll have to take on more women. You won’t have any choice in the matter.’

Mr Tipton’s shoulders sagged at the prospect.

‘And Master John is the head of the household,’ Mrs Tipton continued. ‘His wishes have to be respected.’

Emily was impressed at Mr Tipton’s resolve, but he was definitely showing signs of succumbing – all three of them could sense it.

‘I know the land and the animals, Mr Tipton. I love this farm. Who better to be by your side?’

‘Mmm.’ He scratched his chin.

‘If it turns out that I’m not any good at it then I’ll leave,’ she said.

‘You’ll have lost nothing,’ John said. ‘But you’ve everything to gain.’

Mr Tipton narrowed his eyes, suspecting he’d been ambushed. ‘And what does your mother say?’

Emily exhaled. He had them there.

‘She’s coming around to the idea,’ John said. Even without the financial problems, Uncle Wilfred storming out and John returning to the Front, Mother wouldn’t have given a moment’s thought to Emily’s desire to become a land girl since she dismissed the idea months ago. But Mr Tipton didn’t need to know that.

‘If only those new girls had half your stamina, but I can’t go against your mother’s wishes. If she says no, then the answer’s no.’

‘Very well, it’s a deal then.’

Emily searched John’s face for a clue as to what exactly he knew that she didn’t. Had John managed to persuade Mother too?

‘That’s sorted then.’ Mrs Tipton rubbed her hands together.

‘Don’t look so worried,’ John whispered. ‘We’ll win Mother over, you’ll see.’ He cleared his throat and raised his voice.

‘Go on then. Shake the man’s hand.’ She spat on her hands like she’d seen men do in West Malling on market day, clenched his fleshy palm tight and pumped it for all it was worth.

‘She has all the makings of a land girl this one,’ said Mrs Tipton.

They were halfway there. Please, oh please, let John be right about Mother.

*

Dearest Emily,

I have been told I go on leave tomorrow. I know what you said, my dear, but I am ever hopeful of an encounter with you, no matter how brief, to brighten my spirits and warm my heart for my return to Blighty. I will be passing through King’s Cross between one and two o’clock on Thursday, I shall pin a hankie to my lapel, so that you might recognise me.

Fondest wishes

Theo

‘Do you realise what time it is?’

Emily held her breath and froze at the top of the ladder, steadying her brimming basket of cherries. She’d lost track of time. Working did that to her: the whole day flew by and she didn’t notice.

‘Is it just you?’ she called down.

‘Of course,’ John said with amusement in his voice.

‘You aren’t going to tell Mother on me, are you?’

‘Have I ever yet?’ John asked as she steadily clambered down from the canopy of the red-dotted tree and jumped the last few steps, only noticing now that all of the other workers had emptied their baskets and finished up for the day.

‘You’re running out of time to convince her,’ Emily said, lugging her cherries to the large bathtub-shaped bin and tipping them out. ‘I might just borrow your old work clothes, register with the Corps, and let her try and stop me.’

‘Better I think if you have her blessing,’ John said. ‘One war is quite enough.’

Emily propped herself on a rung of her ladder. She’d never volunteer without Mother’s approval and they both knew it. She didn’t have it in her to disappoint or disobey. She might tug and pull at the apron strings and sneak about on the farm when Mother wasn’t looking, but she wouldn’t cause problems when the family already had enough.

John examined a cherry. ‘You do know that Mother needs you more than she lets on. She’s never been good at putting these things into words. But I can’t see a reason you couldn’t work on the farm and go home to her at the end of the day.’

‘She says it won’t look good to the young men she invites over to meet me. Apparently being outspoken counts against me as it is, I need to at least look the part.’ She sighed. ‘I suppose if we need the money I will have to assist the search for a husband.’

John popped a cherry into his mouth. She examined his face, waiting for him to say more, but he was checking his watch again. ‘John, Mother isn’t the only person who can’t put things into words. Are you going to tell me what went on with Uncle Wilfred the other day?’

‘Nothing. A reunion,’ he said. ‘We ought to go.’ For his last night John had invited some guests over for supper at HopBine. ‘You know Lady Radford is always the first to arrive. We can’t have her steering the conversation.’

He didn’t catch her eye. He was too brave to admit it, but it was obvious he would stay on with them if he could.

She put a cherry into her mouth and savoured the burst of sweetness. She contemplated asking him about the conversation she’d overheard, but she didn’t want him to know she’d been sneaking around listening in, and her hurt at being excluded from the discussions might seep through and with so little of his leave left there was no place for recriminations.

They walked back across the paddock towards HopBine in silence, but as they approached the cut-through in the hedge by the cedar avenue, she pulled him back.

‘If there is anything I can do to help, anything at all … I don’t like to think you’re carrying a burden, or that I’m being left out because you think I can’t cope, because I can.’

John ran his hand through his hair and cast a lingering glance towards the gables of the house their father had built. ‘I know. But you mustn’t worry, everything has been taken care of. There’s no urgency to find a rich husband.’ He winked. ‘And besides, you’re looking after Mother for us, which is a huge weight off my mind, I can tell you,’ he said. But there was something else, he was searching her face as if trying to decide whether to say it, and then he blurted out: ‘If anything should happen to me … once I’ve gone …’

‘No!’ she said. ‘Please don’t start with that, John. Nothing will happen to you. Do you hear me?’ He’d never admitted to his own mortality before now. ‘You’re to come home safe and sound.’

‘I’ll do my best. But if I’m injured I need you to promise me that you and Mother will pull together and accept the decisions that have been made. It won’t do to have the family divided, and Mother will count on you. I have said much the same to Cecil, and as much as I love my brother, I recognise that he is too caught up in changing the world to ever put the family first – so it will fall to you. You have a good sense of responsibility and the family will depend on that.’

‘John,’ she said, ‘you’re scaring me. The way you’re talking, it’s so final. Please stop.’

‘Emily, the war is worse than I’d ever imagined. I believed them when they said it would be over by Christmas, that I’d be home by now, but there really is no sign of it ending, or even easing off.’

Emily had read the Bryce Report about German brutality in the papers and the sinking of the Lusitania by a German U-boat, killing more than a thousand people. All the news was so remote though, surely the danger wasn’t so great for her capable brother.

He reached inside his suit jacket and removed a small diary. ‘In these book pages, I’ve recorded the name, number and trade of every man I’ve lost.’ He held the small, dog-eared book aloft. ‘Their faces come to me in my dreams, memories of a joke they once made, their nickname, a habit. I harbour the knowledge that I censored their letters, read their personal messages, tried to check but not intrude. All are dead or lost now. I’m sorry.’ His voice had reduced to a whisper. ‘I’ve shocked you.’ He took hold of her hand. ‘You shouldn’t know any of this, how bad it really is – it’s best that you don’t, but it’s why I have to ask you to promise me to take care of Mother and make the best of the situation that befalls you.’

She levelled her gaze, her own body stiff as if trying to repel the truths John had just shared.

‘We’re in trouble, aren’t we?’ she asked, doing her best to match her tone with his own determined and brave one.

‘We should have sold up, before the war. I’ve made mistakes.’

‘Well, I’m glad we didn’t. This is our home.’

‘That’s as may be, but we have to be practical now.’

‘And is that why Uncle Wilfred came out of the woodwork?’

‘He offered to help, yes.’

At least John had told her the truth, and not excluded her again. He saw her as an adult and an equal, even if Mother didn’t.

‘Was it wise to take from Wilfred, do you think?’ Father had feuded with his brother for a reason; surely they couldn’t overlook that.

He shook his head. She wouldn’t push him. A tear ran down his cheek as he slid his diary back in his pocket, and she was crying too. It was no secret that war was awful. Theo had been more candid in his letters though much of what he wrote was censored. But John had been so cheery, he’d given the impression that he was living the charmed life he so deserved. None of the men should endure what John had just alluded to.

She offered him her handkerchief, swallowed the huge lump of emotion in her throat. ‘You mustn’t lose hope,’ Emily told him. Her voice broke; her bottom lip trembled. ‘You’re terribly brave. And I want to match that by taking care of things here as best I can. You just concentrate on staying safe, and I’ll keep things going until you come home.’

*

The primrose yellow hallway at HopBine was already buzzing with guests when they returned. Emily announced their ‘hero’ and a round of applause broke out. The guests shrunk to the edges to make way for him.

Emily’s mother pinched her arm, and hissed into her ear to get changed. The blood-red cherries had stained the front of her white skirt.

‘And put on stays.’ Mother shook with rage. ‘Do you think nobody can tell?’

When Emily came back down, Lady Radford and her red-haired daughter, Clara, had cornered John. Clara had always been sweet on John, and Mother had always liked the idea of John marrying into a titled family, but John hadn’t felt the same way. He’d said she was too timid and willing to let her Mother speak for her, that a relationship with her would be a marriage with his mother-in-law. Interesting then, that with their financial problems Mother still placed her brother’s wishes above the family’s need, whilst encouraging Emily to marry anyone who came along.

‘Finch Hall is quite transformed. You must visit,’ Lady Radford was telling Mother and John. ‘The billiard room is a store. The smoking and drawing rooms are wards. I have to remind myself that it was once my home and not always a hospital.’

‘It’s wonderful to put the house to such good use,’ John said, though they didn’t need any encouragement and Mother was craning backwards, trying to attract the attention of Norah Peters.

‘Lady Clara is responsible for book-keeping,’ Lady Radford continued. ‘And you’re in charge of dispatching packages, aren’t you?’ she said, addressing Clara.

‘Mother has even conceded that I can push the soldiers around the lawn.’ Lady Clara raised her eyebrows.

‘We’re quite a formidable team aren’t we, dear?’

Emily forced a smile. ‘How wonderful,’ she said. Clara was so much more confident now she was a war girl. Even John was looking at her anew as if he didn’t recognise this new independent woman before him. He’d better not fall in love with her. She didn’t want to spend any more time with Lady Radford.

‘Although much smaller, you could volunteer HopBine House as a convalescent home for the men recovering from their treatment up at Finch Hall.’ Lady Radford surveyed the hallway and the upstairs. ‘You’d be able to offer ten beds here, quite easily.’

‘Oh no. I don’t think so,’ Mother said flatly. ‘I think we’ve done enough for this war – what with John amongst the first to join up. And I’m terribly busy with the knitting and sewing parties and putting together packages.’

John mouthed ‘go on’ to Emily, but anything she might say would only antagonise Mother for putting her on the spot in front of Lady Radford.

‘Mr Tipton is also cultivating more land for crops,’ John reminded Lady Radford. ‘He’s reducing the land given over to hops and setting more by for important crops like potatoes. For which he will need more manpower.’

Womanpower, was on the tip of Emily’s tongue, but Mother was tugging at a brooch that had become enmeshed in her lace trim and the look on her face forced Emily’s mouth shut.

‘And how is he managing without his labourers?’ Lady Radford asked, either oblivious to the tension or because of it. ‘You took many men with you when you joined up, did you not?’

Mother’s face was set while John explained that Mr Tipton wasn’t as young as he was, and they’d not been able to find enough help, how he was struggling to keep up with the demands from the government, and how the village women had proved troublesome, but that the Board of Trade were training up educated women to lead the volunteers and supervise them on the farmer’s behalf.

‘Tremendous idea,’ Lady Radford said. ‘The village women will be an asset, I’m sure, with the right leadership.’

Emily dared to meet her Mother’s gaze. Her lips were tightly pursed. She’d been right – it would never be that easy to convince her.

Lady Radford turned towards Emily, the penny finally falling into place with a clunk they could all hear. ‘Emily! A young, strong girl like you, who isn’t afraid of getting dirty, should be put to work. You shouldn’t be knitting, you must leave the lighter, less taxing work to the older women.’

Mother’s back straightened, her arms folding across her stomach. ‘I couldn’t spare her,’ Mother said.

‘Really?’

‘And she has a sweetheart of course,’ Mother added. ‘A charming young officer, by all accounts, from a good family.’