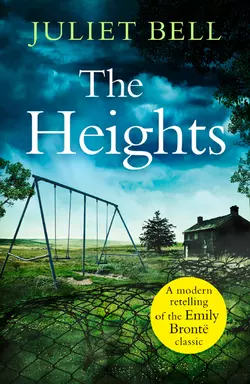

The Heights: A dark story of obsession and revenge

Juliet Bell

#2 in Yorkshire Post’s ‘Pick of the Best Books’The searchers took several hours to find the body, even though they knew roughly where to look. The whole hillside had collapsed, and there was water running off the moors and over the slick black rubble. The boy, they knew, was beyond their help.This was a recovery, not a rescue.A grim discovery brings DCI Lockwood to Gimmerton’s Heights Estate – a bleak patch of Yorkshire he thought he’d left behind for good. There, he must do the unthinkable, and ask questions about the notorious Earnshaw family.Decades may have passed since Maggie closed the pits and the Earnshaws ran riot – but old wounds remain raw. And, against his better judgement, DCI Lockwood is soon drawn into a story.A story of an untameable boy, terrible rage, and two families ripped apart. A story of passion, obsession, and dark acts of revenge. And of beautiful Cathy Earnshaw – who now lies buried under cold white marble in the shadow of the moors.Two hundred years since Emily Brontë’s birth comes The Heights: a modern re-telling of Wuthering Heights set in 1980s Yorkshire.Readers love Juliet Bell:“A genuinely gripping book, cleverly re-telling the story of Wuthering Heights in a convincing modern context… A brilliant achievement. Highly recommended.”“Excellent modern re-telling of Emily Bronte's classic.”“The Heights is an edgy and compelling read”“A fantastically absorbing read”“gripping and dark and an absolute triumph!!”“Excellent read.”

Two hundred years since Emily Brontë’s birth comes The Heights: a modern re-telling of Wuthering Heights set in 1980s Yorkshire.

The searchers took several hours to find the body, even though they knew roughly where to look. The whole hillside had collapsed, and there was water running off the moors and over the slick black rubble. The boy, they knew, was beyond their help. This was a recovery, not a rescue.

A grim discovery brings DCI Lockwood to Gimmerton’s Heights Estate – a bleak patch of Yorkshire he thought he’d left behind for good. There, he must do the unthinkable, and ask questions about the notorious Earnshaw family.

Decades may have passed since Maggie closed the pits and the Earnshaws ran riot – but old wounds remain raw. And, against his better judgement, DCI Lockwood is soon drawn into a story.

A story of an untameable boy, terrible rage, and two families ripped apart. A story of passion, obsession, and dark acts of revenge. And of beautiful Cathy Earnshaw – who now lies buried under cold white marble in the shadow of the moors.

The Heights

Juliet Bell

ONE PLACE. MANY STORIES

Contents

Cover (#u87940c29-859a-5643-b118-557029ef8b5b)

Blurb (#u064eef9a-76bb-5304-b0bb-7aeb3a8af8e6)

Title Page (#u32c40b7b-6428-52b4-9892-0d8ca6a9fddd)

Author Bio (#ua630aed7-9e77-57ff-b0f1-d26141956f2d)

Acknowledgements (#u3824f59e-bfad-5346-a99a-3710ec6a0509)

Dedication (#ud68555f2-f665-59c9-8711-e9a69e3324f3)

Prologue (#ulink_3b5d985a-341a-5d7a-a698-45d196e81270)

Chapter One (#ulink_34158a01-4629-5b5f-af65-140c35beff5b)

Chapter Two (#ulink_52167501-0c9b-5bff-be3c-b9f2a58acbd1)

Chapter Three (#ulink_77b5f76e-4a47-532b-88ea-d3e0901b1abb)

Chapter Four (#ulink_99d67704-92fd-5f40-a3f1-37aa2d6ab725)

Chapter Five (#ulink_d855fdc8-6760-54ec-aa5c-72b2f377a4a4)

Chapter Six (#ulink_7b8acd92-40b4-5010-9691-94cc88e8da13)

Chapter Seven (#ulink_02b14ead-5295-53ec-8073-41ac38b1d179)

Chapter Eight (#ulink_7eb5dc54-a5a6-5a9e-8f7f-9ca642814f75)

Chapter Nine (#ulink_3b6af27d-eb04-5997-a4ce-e89da47a0703)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

JULIET BELL is the collaborative pen name of respected authors Janet Gover and Alison May.

Juliet was born at a writers’ conference, with a chance remark about heroes who are far from heroic. She was raised on pizza and wine during many long working lunches, and finished her first novel over cloud storage and Skype in 2017.

Juliet shares Janet and Alison’s preoccupation with misunderstood classic fiction, and stories that explore the darker side of relationships.

Alison also writes commercial women’s fiction and romantic comedies and can be found at www.alison-may.co.uk (http://www.alison-may.co.uk).

Janet writes contemporary romantic adventures mostly set in outback Australia and can be found at www.janetgover.com (http://www.janetgover.com).

Acknowledgements (#u45ecfadd-ffc2-50be-9f56-d94f66a5f50f)

This book was written with the help and support of many people.

First we must thank Emily Brontë for Wuthering Heights. Adapting her timeless story to our modern world was a huge challenge. We hope we’ve done her justice.

Many thanks to Jon Sawyer, for sharing his memories of troubled times and the picket lines and inspiring some of the key moments of the story.

Our thanks also go to our agent Julia Silk for believing in us and in this book, and to our editor, Clio Cornish, for her enthusiasm and love for the story we were trying to tell.

Writing a novel is a curiously solitary task, even when there’s two of you, so we must also thank all our friends and family for supporting us during the process. Special thanks to all our friends in the RNA, especially the wonderful women of the naughty kitchen. And extra special thanks to John and Paul for, well, for everything really.

And finally – thank you, dear reader, for picking up this book. We hope you enjoy it.

Dedicated to Emily Brontë, for creating a world with the enduring power to inspire readers and writers to this day.

Prologue (#ulink_6d482e6a-43f3-5717-a849-f8947a526109)

Gimmerton, West Yorkshire. 2007

The searchers took several hours to find the body, even though they knew roughly where to look. The whole hillside had collapsed and, although the rain had cleared, there was water running off the moors and over the slick black rubble. The searchers were concerned about their own safety on the unstable slope. The boy, they knew, was beyond their help. This was a recovery, not a rescue.

Twice during the search, the hillside started to move again, and the searchers held their breath. The blue hills were nothing but mine waste. There was no substance to them. They were as fragile as the lives of the people who lived below them on the estate that clung to the land around the abandoned pithead.

Some of the searchers had worked in that mine. Years ago. The boy they were searching for was one of their own. Almost. He had the right name, even if most of them had never laid eyes on him. They knew his family. His grandfather had worked beside them at the coalface. His uncle too had been one of them. Not the father, mind. But still, they weren’t going to leave the lad buried beneath the landslip.

The family weren’t out there on the slope. Maybe the police had told them to stay behind. But maybe not. Maybe they just hadn’t come.

They’d been looking for a couple of hours when the photographer from the local newspaper arrived. He was told to wait safely beyond the edge of the slip. But he was carrying an array of big and expensive lenses. His camera would go to the places he couldn’t.

The sun was sinking when they found him.

One of the searchers had started yet another small slip, and as the rock slid away, almost like liquid, part of the body was exposed. Carefully they had pulled him free.

The boy hadn’t died easily. Father Joseph, down at St Mary’s, was an old-fashioned priest, but there was no way this lad was going to have an open casket. His body had been pummelled by the sliding rock. The rain had washed most of the blood away, but it was still enough to make one of the men turn away and heave into the scrubby grass.

Surprisingly, the boy’s face was hardly damaged at all. Just a couple of small scrapes and a cut on his temple.

The team leader removed his rucksack and dug inside to find a body bag. Carefully, they lifted the boy and put him inside. There was a sense of relief when the bag was closed.

They carried him down from the hills. The photographer followed. He took a few pictures, but then seemed to lose interest. As soon as they reached the road, the photographer broke away and walked quickly to the warmth of his car.

The searchers carried the body to the ambulance and waited while he was gently placed inside. Then they too dispersed.

The ambulance and the police were the last to leave. The ambulance was destined for the morgue. The police car turned into the estate and parked outside one of the few houses that wasn’t boarded up and deserted.

The young constable got out, and carefully placed his hat on his head and straightened his uniform jacket. That’s what you did when you brought bad news to a family, even one that hadn’t bothered to come and join the search.

He walked up to number 37 Moor Lane and knocked on the door.

Chapter One (#ulink_0efacecf-1013-5958-811b-6a5b6ae063c4)

Gimmerton. 2008

This was the place he had almost died. Lockwood shivered. In front of him, the chain-link fence was rusted and sagging. The sign hung at an angle, the words NO TRESPASSING all but covered with dirt and grime. Beyond the fence, in the grey light of the overcast afternoon, the buildings looked dark and decayed. Odd bits of iron, stripped from the disused mining machines, lay scattered about the ground and weeds were reclaiming their place in the filthy wasteland of the deserted pit. One building was open to the elements, the remains of its roof lying in a twisted heap between the crumbling brick walls. Not a single pane of glass remained intact. The men of this town had good throwing arms. Stones hadn’t been their only weapons. Nor had windows been their only targets.

Lockwood reached into his pocket and retrieved the piece of metal he’d carried with him every day for more than two decades. The nail was twisted and bent, distorted almost beyond recognition when it was fired through the side of the police van. The newspaper reports at the time had declared it a miracle no one was injured as the nail ricocheted around the interior. Lockwood knew better. A tiny white scar on the left side of his neck showed how close death had come. After everything he’d seen in this job, that was the place his brain took him whenever he let his guard drop. To this day he still woke, sweating at night, hearing the sound of the nail gun beside his ear, and the screech of metal as the nail tore through the body of the van. He could still feel the sharp stab of pain in his flesh.

Lockwood told himself he was no coward. Even then, working with the riot squad, he’d expected danger. The miners were tough, and they were angry. Desperation had seeped into the bones of their community. They were about to lose their jobs. More than that, they were about to lose a way of life that had been with them for generations, the only way of life they knew. They were looking for a fight. He’d been green and keen, and could handle himself. He’d been trained to deal with anger, and there’d been so many moments in his career when something could have gone wrong. There’d been moments when things had gone wrong, but those weren’t the moments he carried with him. Instead he kept hold of this one, as clear and solid in his memory as the nail in his hand. Maybe because that was the first time things had gone wrong. Maybe because they’d never caught anyone. Maybe because of the randomness of the attack. But stay with him it had.

They might not have caught the person who did it, but Lockwood knew who it was. The squad had been out of the vehicle seconds after the incident, breaking up the crowd pounding on the sides of the van. As he struggled in the melee, his neck damp with his own blood, Lockwood had looked towards the nearby houses and seen him. A dark youth, with hatred on his face. He’d been no more than fifteen then and already familiar to the police. He was carrying something in his hands. Lockwood couldn’t see it clearly, but he knew in his heart it was the nail gun, and somewhere in amid the shouting he’d heard the words: ‘That Earnshaw kid.’

By the time Lockwood had fought his way through the crowd the youth was gone. He’d looked at the maze of narrow streets and identical houses in the Heights estate, and known he wouldn’t find him. They had investigated for a few days, but found nothing they could take to court. There were more pressing matters than one split second amid weeks of violence. Nobody was charged, and the incident was forgotten by everyone except Nelson Lockwood.

Darkness was falling as he turned away from the mine and got back into his car. He pulled away from the gates and began to retrace the route he’d followed that morning. The estate was even shabbier than before. Most of the people had left when the mine closed. Rotting boards covered the windows of the deserted pub. Graffiti scarred the walls of the empty shops and houses. Here and there, curtains or a light in a window showed that a house was occupied. For some people, Lockwood guessed, there was simply nowhere else to go.

His goal was the very last row of houses. A couple of the foremen had lived up here. They were the best paid and most trusted of the mine’s employees. They had also been the leaders of the strike. And they always protected their own. The hotheads who had thrown the bricks and started the fights. And a kid with the nail gun he’d stolen from the mine.

Lockwood knew what he would find at the far end of this street, where the town ended and the wild hills began. Since his last visit, someone had turned two small houses into one. It was larger than the houses around it, but not better than them. The aura of neglect and decay was almost palpable. It would take more than a coat of paint or some new guttering to erase the memories that lingered in those walls.

Lockwood didn’t need to see the light in the windows to know that the house was still inhabited. He’d checked that before leaving London on this final trip to Gimmerton. He drove past without stopping. There was plenty of time.

It took only a few minutes to drive from the past back to the present. The new estate had been built on a gentle slope below the moors. The houses were all detached with well-tended gardens. They were big and new and looked away from the mine, across the valley towards the lights of the town. The people who lived in the new estate weren’t part of the old world. They sent their kids to the right schools and drove their big four-wheel drives to Leeds and Sheffield to work in offices, rather than toiling beneath the ground they lived on. Their wives ate lunch, rather than dinner, and went shopping for pleasure not for provisions. The history of this place didn’t touch the Grange Estate.

Except for one small corner.

The house that had given the estate its name sat slightly removed from the new buildings, surrounded by a large garden. Thrushcross Grange was Victorian – the big house built for the mine owners back in the day, then used by a succession of managers after the pit was nationalised. It remained aloof from the newer buildings that surrounded it; with them but not a part of the town’s new story. Thrushcross was the old Gimmerton.

After parking his car, Lockwood removed his bag from the boot and slowly approached the house. Despite the need for a new coat of paint, it had survived the new reality far better than the Heights. But still the memories lingered. He stepped through the door and made his way to the reception desk where a young woman with an Eastern European accent waited to check him in.

‘Welcome to Thrushcross, sir. Do you have a reservation?’

He nodded. ‘Under Lockwood.’

She stared at the screen. ‘That is for a week?’

‘I’m not sure. It might be longer.’

‘It is quiet time, sir. There will be no problem to extend the booking if you want to.’

It felt strange to be walking the same hallways as the people who had intrigued – no, obsessed – him for so many years. As he entered his room, with its high, embossed ceiling and big bay window, he wondered which of them had slept here. He looked around the room trying to picture them, but suddenly shivered. It must be the cold wind off the moors, and he was tired after the long drive from London. The guesthouse had a restaurant. He’d go down and get something to eat and maybe a whisky before he tried to sleep.

Emerging into daylight the next morning, Lockwood was surprised to find a bright, still day. His restless sleep had been punctuated by the deep moaning of strong winds blowing off the moors, and the tapping of heavy rain against his window. Perhaps he’d been dreaming, his mind disturbed by reconnecting with the past.

Not even dazzling sunshine could make the town centre look appealing. It had changed in twenty-four years. It had never been smart, but now the decay was overwhelming. The few remaining shops were at the bottom end of the market – charity shops, pawnbrokers, pound stores. The two small pubs didn’t look at all inviting. Nor did the only food outlets; a grease-stained chippie and an Indian. A tired looking Co-op also served as post office. Lockwood had seen a nice pub and restaurant just outside the town, on a hill with a glorious view of the moors. That must be where the people from the new estate went. Their road skirted the town centre to take them away from here without even passing through the old town and risking getting the dust of poverty and hopelessness on their shiny new cars.

In a tiny town square, a group of youths sitting at the base of a statue watched through hooded eyes as Lockwood drove past. He remembered that statue. It was of the town hero, a footballer who had made it good in the first division, back when the first division really was first. It said a lot about Gimmerton that Lockwood had never heard of the town’s most famous son. There were more people standing near the pub. Men leaning against the walls, smoking as they waited for the doors to open. There was nothing else for them to do.

It hadn’t always been like this.

Lockwood parked his car outside the church. It had beautiful arches over ornate, stained-glass windows and a wide staircase leading to dark wooden doors. It was newly painted, perhaps to prove that God hadn’t entirely forsaken Gimmerton. Across the road from the church was a magnificent gothic edifice, no doubt built when the mine was flourishing. The stone was stained with soot. Three storeys above the ground, ornate Victorian gables towered over windows that were dark and empty. Above the door, a carving announced that this was the Workingman’s Institute.

Or rather it had been, when there was work.

Much of the strike had been planned and run from this building. Until the union had been kicked out. And ten years later, when the pit finally closed, so too had the Institute. It was open again, but served a very different role. The men and women who walked up those steps now were going to the job centre to sign on, hoping to avoid the interest of the social workers who occupied the floor above. But this morning, that was exactly where Lockwood was heading.

The cavernous hallway echoed slightly as he made his way to the stairwell. At the top of the steps, a young mother and two small children sat on orange plastic chairs in the waiting area. Their clothes looked as if they had come from one of the charity shops on the high street. The reception desk was at the back of the large, unloved room. Behind it stood a woman about Lockwood’s own age. She had the look of a someone who’d left her better days behind some years ago and her grey hair was cut in a short, severe fashion that did nothing to flatter her lined face. She glanced up as he entered and frowned.

‘Yes?’

‘I’m looking for Ellen Dean.’

The shifting of her eyes told him he had found the woman he was looking for.

‘And you are?’

‘DCI Lockwood. I have an appointment.’ He pulled his warrant card from his pocket and held it up for her to see.

‘This way.’

She led him to a small office. She took a seat behind the cheap wooden desk while Lockwood helped himself to another orange plastic chair. Miss Dean sat primly, her mouth firmly shut, waiting for Lockwood to begin.

‘As I mentioned in my email,’ he said, ‘I’m following up on a couple of incidents recently that may shed light on an unsolved case dating back some time.’

‘What case?’ Her eyes narrowed.

Lockwood sensed she was going on the defensive.

‘It goes back to the strike,’ he said, hoping to reassure her she wasn’t his target. Not now, at least.

‘That’s long gone. People don’t talk about those times much around here.’

‘I’m not so much interested in the strike, as in some of the people who were here back then. The Earnshaws and the Lintons.’

He waited for her to say something, but she simply sat there, her eyes narrowing and her mouth fixed in that firm, defensive line.

‘I believe you had dealings with both families in your role back then with social services.’

‘In this place, most people had dealings with social services.’

Lockwood nodded. ‘I’d like to start with the Earnshaws. In particular the youngest boy. Heathcliff.’

A shadow crossed her face. He could almost feel her defences rising. Was it guilt, he wondered. He’d been in plenty of meetings with plenty of social workers over the years. He’d sat through child protection conferences, and even gone out as muscle when they took the kids away. He’d seen the good ones, the ones that cared too much, the ones that didn’t care at all, and the ones that got worn down by the job. Now, here was Ellen Dean. He wasn’t sure which type she was. He reminded himself that he was here to do a job. However personal this investigation was, he was a professional. He would do what the job demanded. He arranged his face into a more sympathetic expression.

‘I’ve read the file,’ he said. ‘There’s not much detail there. The child apparently just turned up.’

‘Old Mr Earnshaw brought him back from a trip. Liverpool.’

‘And you never thought too much about it? You didn’t question where the boy came from or how Earnshaw got hold of him?’

The woman across the table bristled. ‘It was a private fostering arrangement.’

‘Really?’ Lockwood’s eyebrow inched upwards.

She nodded. ‘Perfectly legal. There was a note from the mother.’

‘That’s not in the file.’

She shrugged. ‘It was a long time ago. Things were different then. He were never reported missing. And besides…’ Her voice trailed off.

Lockwood felt a glimmer of hope. He was beginning to understand Ellen Dean now. He knew how to get what he wanted from her. ‘Please, Miss Dean…’ He leaned forward, hoping to suggest to her that they were co-conspirators in some secret endeavour. ‘Anything you could tell me about the family will help.’

The woman pursed her lips. ‘I’m a professional. I don’t engage in gossip.’

There it was. Lockwood forced himself to resist the smile that was dragging at his lips. She knew something. And in his experience, anyone who professed not to be a gossip usually was. He nodded seriously. ‘Of course not. But if there were things you think I ought to know.’ He paused for a second as she leaned slightly towards him. ‘In your professional opinion, of course. And to help with the old case. It would be good to get rid of the paperwork on it.’

‘Well…’ The woman glanced around as if checking no one could overhear. ‘There was them that said the boy was his.’

That was interesting. ‘Was he?’

‘Don’t know. He looked like a gypsy. All dark eyes and wild hair. Talked Irish an’ all.’

‘And the mother?’

‘She never came looking for him. Back then, I had my hands full. It was desperate round here. The winter of discontent and all that. There were families what needed my help.’ She straightened her back. ‘I had important things to do. More important than wondering about one brat. He was fed and housed. He was safe. There were plenty who weren’t.’

‘Of course.’ He smiled at her.

A sudden crash outside the room was followed by the sound of a woman yelling at her child. A few seconds later, the child started screaming. That was his cue.

‘I can hear you’re busy, Miss Dean,’ he said getting to his feet. ‘Thank you for talking to me. I may need your help again.’

She nodded brusquely as she got to her feet. The closed, hard look on her face didn’t bode well for the family who dared to create a disturbance in her office.

Lockwood spent the afternoon at the town’s small library, also housed in the Workingman’s Institute. The seats were empty, and a lone librarian showed him the way to their old newspaper files. The library had not yet entered the twenty-first century. Back issues of the local newspaper were on microfiche, not computer, and by the end of the day his eyes felt dry from staring at the viewer. He hadn’t learnt much. He’d found a lot of stories about the miners’ strike and the pit closure and the deaths that had brought him back. But nothing he hadn’t already read. He had even seen his younger self in one of the photos. His face was obscured by his helmet and shield, but he knew himself. Even after all these years, he felt a twinge of pride that he had followed orders and done the job that was required of him.

The current job, however, was looking pretty hopeless. Heathcliff had been and remained a mystery. There was nothing to tie him to any crime.

Lockwood was an old-style copper. He believed in old-fashioned investigation. People were the answer. Someone always knew the truth. The trick was to get these people to talk to him. They didn’t like strangers, and most of all they didn’t like a copper from the south. Old enmities died hard around here. He had a lot of legwork in front of him. And he didn’t have much time. He was retiring soon. This investigation was, on paper at least, official, but Lockwood knew he’d been given the case review as a favour. No one thought he would find anything new. This case was so cold there were icicles on it. Dusk saw him back on the Heights estate, sitting in his car at the end of a street made gloomy by the lowering clouds. A small beam of light was visible from the window of the shabby house at the top of the rise.

When it was fully dark, Lockwood got out of the car and walked slowly up the hill to stop in the deep shadows beside an old and boarded-up terrace across the road from that single light. He watched for a while, but saw nothing through the grimy curtains. He crossed the road and made his way down a path between two houses into the yards at the back of the terrace row. There was a gap in the fence wide enough to let him through. From the back of the deserted neighbouring home, he could see more lights. These windows had no curtains, and for a moment he thought he could see a dark shape moving inside. He stepped onto a pile of mossy timber and grabbed the top of the fence to pull himself up for a better look.

The girl’s hand came from nowhere. It grabbed his wrist, the bare fingers pale in the dim light and icy cold.

Lockwood gave a startled cry and smashed his free hand down into the girl’s flesh, driven by a desperate urge to stop her touching him. His foot slipped and he fell backwards. He crashed to the ground, grimacing in pain as his shoulder hit something hard hidden in the long grass. A moment later, the door of the house next door crashed open.

‘Cathy? Cathy?’

Lockwood bit back a moan of pain and sat up, to peer through a gap in the rotting fence.

The boy was now a middle-aged man, but Lockwood knew him in an instant.

‘Heathcliff,’ he breathed.

Time had not been good to him. His dark hair was still worn long and untidy, but now it was heavily threaded with grey. Where once he’d been muscular and lean, he was now painfully thin. His face was gaunt and lined and his eyes were sunken dark holes. He looked wildly around.

‘Cathy? Are you there?’ Heathcliff called in a voice shaking with emotion.

No answer came from the silent night.

Lockwood didn’t dare move. Heathcliff waited, staring out into the blackness and muttering something Lockwood couldn’t hear.

Something moved in the corner of Lockwood’s vision. He turned his head, but there was nothing or no one there. A heartbeat later, a soft white flake drifted to the ground. Followed by another. And another. Within a minute, heavy snowflakes obscured his vision and he began to shiver and the temperature dropped even further. Still, Heathcliff didn’t move. Just as the cold was about to drive Lockwood to revealing himself, a shout from inside the house caused Heathcliff to stir. Muttering loudly, he turned away and retreated inside the house, slamming the door behind him.

Lockwood waited no more than a few seconds before slowly getting to his feet. He risked another look over the fence, but there was no sign of the girl with the icy hands.

Cathy?

His mind conjured up a picture of a dark-haired girl with wild hair. She hadn’t been beautiful. Not really. But something about her had been strangely compelling. She had been Heathcliff’s constant companion, matching his every wildness. But then, something had happened to drive them apart. He knew that much.

Hers was one of the deaths that had brought him back.

Catherine Linton. Catherine Earnshaw.

Heathcliff’s beloved Cathy.

Chapter Two (#ulink_3ce85121-3fa9-5e76-956e-b45927e00781)

March, 1978

‘Is he for me?’ Cathy peered at the scratchy-haired, dark-eyed boy standing behind her daddy in the hallway. ‘You said you’d bring me back a present. Is he my present?’

‘No, dear.’ Her father set his bags down next to the front door. He didn’t hug her the way he normally did after being away. But Cathy didn’t mind too much. She was far too interested in the boy, with his tatty clothes and hunched shoulders. ‘This is your new brother. His name is Heathcliff and he’s going to stay with us for a while.’

Cathy’s mother bustled out from the kitchen, wiping her hands on a dishcloth. She stopped in mid-stride and looked down at the boy. Her eyes narrowed and her lips almost vanished as she frowned. Cathy knew that look too well.

‘What is that?’ Her voice was hard, the words clipped.

Her daddy shifted from foot to foot. ‘Cathy, why don’t you take Heathcliff upstairs?’

That always happened. Every time there was anything interesting, Cathy got sent upstairs. It wasn’t fair. Mick didn’t get sent upstairs. Mick got to go out round the village with his mates. Mick had even had a ride in a police car. He’d come into her bedroom and shown her the bright-red mark across his cheek where he reckoned a policeman had clipped him round the head. Mick got to have all the adventures.

But not this time. Mick wasn’t here. Getting a new brother was almost as exciting as riding with the police. Maybe more exciting, especially if Mummy and Daddy were going to row about it. And for now it was all hers. Being sent upstairs was not fair at all, but she knew how to deal with that.

‘Come on,’ she said.

The boy followed.

She stopped on the tiny landing. ‘So my room’s down there. That’s Mick’s. Mummy and Daddy sleep in there. Bathroom’s downstairs through the kitchen.’ She looked around. ‘Where are you going to sleep?’

‘Dunno.’

‘Is your name really Heathcliff?’

The boy shrugged. ‘Yeah.’

Cathy wrinkled her nose. ‘That’s not a name. Names are things like Gary or David. Have you got a last name?’

Heathcliff shrugged again.

Cathy sat down on the top step.

Heathcliff hesitated for a few seconds then sat down next to her, squashing himself against the wall, as far away from her as he could get. She sniffed. Did he think she had something catching?

‘What are we doing?’

‘Listening.’ This was Cathy’s secret listening spot. From here you could hear people perfectly if they left the door at the bottom of the stairs open. This time they hadn’t. She had to strain to make out bits. It sounded like her mummy was doing most of the talking. And when she yelled, it was easy to hear her.

‘What were you thinking?’

‘What about his mother?’ Mummy got louder.

‘Did you really think you could just bring him here? That I would cook for him and wash his filthy clothes and treat him like my own children?”

‘Well, I put up with Mick…’ That was Daddy. He was getting angry now too.

‘That’s different. It were for ever ago.’

‘Was it?’

Cathy blew the air out of her mouth so that her lips tingled. Everyone had to put up with Mick. She didn’t want to listen to her parents talking about Mick.

Cathy heard the kitchen door slam. That was it then. Her mother would hide in the kitchen and sulk while her daddy sat in the back room and read the newspaper. There was nothing more to hear.

She turned her attention back to the new boy. ‘Do you play with Sindys?’

He shook his head.

‘Well, what do you do?’

He shrugged.

‘You don’t say much, do you?’

‘Dunno what to say.’

Cathy didn’t know either. ‘You talk funny.’

‘I talk like me mam. You’re the one who talks funny.’

She didn’t. She talked normal. ‘Come on. I’ll show you how to play Sindys.’

Mick Earnshaw strode up the hill towards home. This winter was turning into a pain in the arse. His dad reckoned they were going to bring back the three-day week. That was the last thing he needed – his dad hanging round the house the whole time, winding his mum up even more than she already was. His dad had been away this week, some union thing in Liverpool. He always came back from union meetings ranting and raving about what a waste of space Callaghan was. Mick didn’t care. He probably would when he finished school and got a job. Until then, he had his mates. And as long as the lasses kept looking at him the way they did, he was happy.

He reached into his pocket and pulled out a packet of fags. He lit one and took a deep drag, then stretched out his hand. The scabs across his knuckles had gone now, but he liked to picture the blood, and the bruising, and the looks on his mates’ faces when he’d rammed his hand into the police car. The buggers had all run away after that. They hadn’t seen the copper clip him over the head. Shame, but he’d told them all about it. He’d seen the respect in their faces. That was the important thing.

Mick grinned as he got to the top of the Heights estate. Theirs was the last house in the row. The end of the terrace. Mum reckoned that meant you could call it a semi-detached. Mum needed her head looking at.

He flicked his fag end away, stuck his key in the Yale and opened the door. They didn’t used to lock it during the day, but now you heard stories about neighbours stealing from one another and his mum said you couldn’t be too careful. Mick wasn’t worried about that. Anyone who tried to take anything from him would be sorry.

‘Who is it?’

‘S’Mick.’

His mother came into the hallway. She looked angry, but then, she looked angry most of the time these days. ‘Your father has something to tell you. I’m going to my Ladies’ Group.’

Mick shrugged. His mother was for ever going to her groups at the church. There was a cookery group, and a group for wives, and another group where some old women taught the young women how to do darning and rubbish stuff like that. Half the time, when she said she was going to the church, Mick saw her nip off in the opposite direction anyway.

His dad was sitting in the back room. They never sat in the front room. Mum said that was for Best. Best wasn’t something that happened very often. Dad was wearing his weekday suit. He had one suit for Sunday and one for during the week and a scrappy old one for working round the house. Mick would see the other miners walking along the road in jeans and tracksuit bottoms. They didn’t know how to present themselves. That’s what his dad reckoned anyway. His dad was a cut above.

‘I need you to make some space in your room.’

‘What? Why?’

‘We’ve got someone staying with us.’

‘Not in my room.’

‘Well, he’s a young boy so he can’t really go in with Cathy.’

‘How long for?’

His dad stood up. ‘For as long as needs be. I’ll bring the foldout bed down from the loft. Go clear some space.’

Mick’s chest tightened and his fingers closed into a fist. It was crap – there was no way he was going to share his room with some kid. ‘Why’s he here anyway?’

‘He needed somewhere to stay.’

Mick shook his head. ‘You can’t just bring a kid home. There’s social services and that. Like when Keely Baldwin’s mum went off and it was just her and them babies in the house. Social services took them all away in the end.’

His dad’s face grew dark. ‘This is different. The boy’s staying here. Now go and clear some space.’ He didn’t raise his voice. He didn’t make a fist, but Mick’s legs turned and carried him towards the stairs as surely as if he’d been whacked on the arse.

There were two faces watching him from the landing. Cathy, sitting at the top of the stairs, like always, and this new kid sitting next to her. ‘What the hell?’

The boy had a thatch of thick black hair, above dark skin, and dark eyes, but that wasn’t what Mick first noticed. The first thing he saw was the bright-red shine on his lips and the glittery blue rings around his eyes.

Cathy shrugged. ‘We were practising doing make-up.’

‘He looks like a freak.’

Cathy stuck out her chin. ‘Well, I like it.’

He looked at the boy, but the boy was staring at Cathy, eyes wide. The look on the brat’s face said it all. Cathy had him wrapped around her little finger. Like the old man. In their father’s eyes, Cathy was his little princess. She could do no wrong, while Mick couldn’t do anything right. And now his dad had brought this brat home. Not that Mick cared.

He stalked past them up the stairs, jabbing the boy in the ribs with the toe of his boot as he did. The kid started, but didn’t make a sound. Mick wondered if the brat would cry if he knocked him down the stairs. Maybe one day he’d find out.

Chapter Three (#ulink_1b6541ff-ddfd-51f5-81eb-338a10148596)

March, 1978

Ellen Dean didn’t have time for this. She still had a pile of case notes to write up from yesterday as well as all today’s home visits. She could do without an extra trip to the Heights estate being dropped on her as well. Her boss, Elizabeth – always Elizabeth, never Liz or Lizzie – had handed her a scrap of paper with the address on with some glee. Ellen had no idea why she had to do this today. The kid had only arrived yesterday. Cases like this usually waited a week or two before anyone got around to doing something about them. What did it matter? But oh no! Queen Elizabeth said today, so today it had to be.

Every social worker in the county knew about Collier’s Heights. It was a rite of passage for the new starters and a source of many a well-told war story for the old hands. A lot of their work was up there. The name said it all. The estate had been built for the miners when the pit was new. Back in the day, it might have been a close-knit and happy community, but things had changed. Now it was the roughest end of a rough town. Ellen had only been in this job three weeks, and she’d already been to the Heights twice, tagging along behind Elizabeth, who had taken great delight in sending her junior up there today – all alone for the first time. What Elizabeth didn’t know – what nobody knew – was that Ellen had grown up on an estate not all that different to the Heights. Hard work and a bursary to pay her rent at university had been her escape route. Social work hadn’t been her choice, but it was the only scholarship available, and now it had led her back to the same sort of place she had left behind. This time, however, she was on the other side of the fence, and determined to help other kids the way she had been helped.

She turned her car into Moor Lane, right at the top of the hill to which the Heights clung, and drove slowly along the street, peering for numbers on the rows of identical, weatherworn, redbrick terraces. She was very aware of the groups of lads at the corners, eyeing the car. Here and there she caught a twitch of a curtain or a slam of a door that had stood ajar in welcome a second before. She hadn’t expected any different. She’d grown up doing the same thing.

She pulled up outside number 37 Moor Lane, and picked up the buff-coloured folder from the passenger seat. The Earnshaws. Ray, Shirley and two kids. A boy and a girl. She mouthed the names to herself as she waited for someone to come to the door. She’d learnt that on her first day, when she’d completely forgotten the name of the mother she was coming to see, and the woman had called her a stuck-up bitch and accused her of not giving a shit about anyone. The Earnshaws. Ray and Shirley and… She flipped the folder open. Mick and Cathy. Mick’s entry in the file was longer. Truancy, shoplifting and the odd run-in with the police. Nothing unusual there for a fourteen-year-old kid from an estate like the Heights. The door swung open.

The man was older than she expected. Half the parents she’d met so far were about her own age, if not younger. This man was more her parents’ generation. Smartly dressed, or as smartly dressed as money allowed around here, with a shirt and tie under his faded pullover and hair combed over a slight bald patch. She held out her hand. ‘I’m Ellen Dean.’

The man didn’t respond.

‘From social services?’ She heard the hint of a question in her tone, and hated it. ‘About…’ She stopped. What was the boy’s name? ‘About the young boy.’

‘Heathcliff.’

‘Yes.’

‘You’d best come in.’

His wife was waiting in the back room and offered tea, which Ellen didn’t accept. Mrs Earnshaw tutted at that as she tucked her cotton skirt tightly around her legs and sat down, back straight and stiff, at the wooden table.

‘Shall we go into the front room?’ Mr Earnshaw shuffled slightly from foot to foot. ‘It’s nicer in there.’

Mrs Earnshaw shook her head. ‘I’ve not aired it. This’ll do.’

‘This is fine.’ Ellen took a hard wooden seat at one side of the table and waited for Mr Earnshaw to sit opposite her. She arranged her face into what she hoped was a friendly smile rather than a grimace, and wondered if the Earnshaws could hear her heart pounding.

‘So it’s about Heathcliff?’ Her voice was louder than she intended.

‘What about him?’ Mr Earnshaw’s expression was closed.

‘Well, I understand he’s living here now.’

Earnshaw nodded.

‘Okay.’ Ellen swallowed again. ‘I need to check that everything’s in order…’

‘In order how?’

She took a deep breath, afraid her inexperience was showing. ‘Sort of… well, legally. I need to establish why he’s moved in here and make sure everything’s above board. He’s what… six?’

‘Seven.’ Earnshaw pulled his chair back. ‘There’s papers.’

‘Right. Good. Papers are good.’

Mrs Earnshaw hadn’t spoken or even moved. Ellen gave her a tentative smile as Ray left the table. The woman’s face was stone.

Ray carefully opened a drawer in the dark wooden chest that dominated one wall of the tiny room.

‘A letter from his mother.’

Ellen unfolded the crumpled sheet, apparently torn from a notebook. The writing was wobbly and uneven, as if the writer wasn’t confident forming the letters, but the three short sentences were clear. Heathcliff’s mum couldn’t manage. She wanted him to live with Ray Earnshaw and his family. She didn’t want anyone else sticking their nose in. Ellen was doing just that, but if she didn’t she’d get no end of grief from her supervisor. Besides, it was the right thing to do. Someone had to make sure the kid was safe.

‘Right. Do you have a birth certificate or anything? To confirm that this is his mother. And whether there’s a father around.’

Mrs Earnshaw folded her arms.

Mr Earnshaw was quiet for a moment before he spoke. ‘I don’t. But you can get that, can’t you? Ring up the records place or what have you.’

Ellen nodded. She could. She made a note in her folder. ‘And he’s been registered with the school? As Heathcliff Earnshaw?’

‘That’s right’

Ellen heard the sharp intake of breath from the wife.

‘Could I see him?’ She glanced at the clock. ‘If he’s not in school.’

Mrs Earnshaw stood up, moving towards the door in a way that gave the distinct impression that Ellen’s visit was over. ‘He’s poorly.’

‘Right. It only needs to be for a second.’

Mr Earnshaw shook his head. ‘Shirley’s right. He were sick in the night. He’ll be asleep.’ He shrugged. ‘Can you come back another day?’

‘Right.’ Ellen hesitated. She was supposed to see the boy if she could. Another glance at the clock. He would normally be in school anyway, so she hadn’t really expected to see him. And her next case was across town. She already had another job from the Earnshaws to find the blessed birth certificate, so she had to come back. She shook her head. ‘That’ll be fine for now, I’m sure.’

She heaved a sigh of relief when Earnshaw closed the front door behind her. That poor kid wasn’t coming into a very welcoming household. She couldn’t imagine Shirley Earnshaw pulling some bastard kid to her warm embrace. Still, he had a roof over his head, and there’d be a meal on the table every night. The sound of voices drew her eyes to her parked car. Three teenagers were leaning against it – a boy and two girls. All three had cigarettes hanging from their mouths. It was hard to see past the make-up, but Ellen guessed the girls were not more than thirteen. Fourteen at most.

‘You all should be in school,’ she said as she approached, trying at the same time to appear firm and friendly.

‘What’s that got to do with you?’ the boy asked insolently. He slowly lifted himself away from the car. Taking a last drag on his cigarette, he stubbed it out on the faded red paint on her bonnet.

‘Sod off! You little shits.’ Her carefully cultivated demeanour vanished and the words were out before she could stop them.

The group ‘oooohed’ like an overexcited audience on TV, taking the mick out of her even as they strolled away.

Cathy sat on her step and watched Daddy walk into the back room and shut the door. She didn’t know what the straggly-haired woman wanted, but it was something to do with Heathcliff. Mick was at school. Or at least he was supposed to be at school. He was probably off with his mates somewhere getting into trouble. Cathy should have been at school too, but she’d said she had tummy ache. Her mum wasn’t paying much attention – she didn’t seem to pay attention to much any more – and had grunted that she could stay home. That was all Cathy needed to hear. School was boring. Heathcliff was staying at home today and he wasn’t boring at all.

Cathy ducked up the last couple of stairs and opened the door to Mick’s room. She wasn’t allowed in Mick’s room, but Mick wasn’t here. Heathcliff was sitting on the floor in the corner of the room, his arms wrapped around his knees and his forehead resting on them. The foldout bed he was supposed to be sleeping on was covered with Mick’s stuff.

‘Did you sleep on the floor?’ she asked.

‘What do you care?’ Heathcliff raised his head. There was a bruise on his face.

‘Did Mick do that?’

Heathcliff shrugged.

‘I hate Mick,’ she declared.

‘I do too.’ The scowl on Heathcliff’s face softened a bit. ‘Let’s get out of here.’

Cathy shook her head. ‘We’d get in trouble.’

Heathcliff stood up. ‘I don’t like being stuck inside. Everything’s too small.’

Cathy looked around. That wasn’t true. Everything was normal-sized.

Heathcliff got up and walked to the bedroom window. He looked out and down, then shook his head. ‘This is no good,’ he muttered. ‘There’s no way out here.’

‘My room has a window too,’ Cathy offered.

Cathy’s room looked towards the exposed hillsides and moors behind the estate. There were no houses to be seen, only a couple of old warehouses from the mine, and the blue hills.

‘That’s where I want to go,’ Heathcliff told her.

‘Why?’

‘Cos it’s better than in here. It’ll be just us out there.’

She looked around. It was just them already. Well, apart from her parents downstairs. Maybe Heathcliff was right. It might be good to get away from them.

‘Come on.’ Heathcliff slid the window up as far as it would go. ‘We can jump.’

Cathy leaned past Heathcliff to look out of the window. There was a coal bunker underneath her window, built up against the kitchen wall. But it still looked like a pretty big drop. ‘It’s too far.’

Heathcliff laughed. ‘Well, I’m going.’

She watched him pull his scrawny body up onto the windowsill and stare down at the bunker and the ground beneath them. He was very still for a very long time. Cathy stamped her foot. ‘Get out of the way.’

‘What?’

She pulled him backwards onto the bed and climbed onto the sill. She swung her legs out through the window and screwed her eyes tight shut, before pushing off with her hands to lift her bottom over the frame. And then she was dropping. She landed on her feet on the coal bunker and tipped forward to her knees. She crawled forward. If Mummy or Daddy heard her and came out now she would be in so much trouble. At the edge of the coal bunker she stopped. The roof she was sitting on was about the height of a grown-up but there was a dustbin against the wall. She dropped onto that, and then onto the ground. She’d done it. She spun round. Heathcliff was still watching from the upstairs window. ‘Come on,’ she said in a loud whisper.

He hesitated.

‘Scaredy.’

‘What?’

‘You’re a scaredy.’

‘I’m not.’

‘I did it.’ She grinned. ‘You have to follow me.’

In the window, Heathcliff frowned, and then swung his legs over the ledge and jumped.

They ran past the old warehouses. There were people moving around inside, but nobody cared about a couple of kids bunking off. They stopped running when they reached the blue hills. Heathcliff looked around at the mounds of loose black rock, sparsely covered with grass.

‘What’s this?’

‘It’s from the mine. Everyone knows that,’ Cathy said.

Heathcliff grunted and walked off ahead of her. He was moving so fast, she almost had to run to catch up.

‘Come with me,’ she said and led him towards the tallest of the mounds.

They scrambled up the side, feeling the damp, loose rock sliding beneath their feet. When they got to the top, Cathy sat down on a patch of grass. It was wet, but better than sitting on rocks. Heathcliff didn’t seem to mind either way. He sat down next to her. They sat for a minute. From this angle, she couldn’t see the mine. And the town, in the distance, was almost pretty. After a while, Cathy looked across at Heathcliff. His eyes were wet.

‘You’re crying!’

‘Am not.’ He rubbed the back of his hand across his face.

‘Were too. S’all right. I cry sometimes. When Mummy and Daddy fight.’

‘My mam sent me away.’

He sounded so sad, sadder than anyone Cathy had ever known. She squeezed his hand. ‘I’m glad you’re here,’ she said. ‘I want you to stay for ever. I’ll never send you away.’

He turned towards her. ‘Promise?’

Cathy nodded seriously. ‘I promise.’

Chapter Four (#ulink_68455b01-537c-5ba8-9860-898550f2e885)

January, 1983

Shirley Earnshaw paused on the steps of the Methodist Hall and undid her headscarf, patting her hair into place before she pushed open the door. She took a deep breath and steeled herself for what she knew was coming. It was five years since Ray had brought that boy back from Liverpool. Surely these women had gossiped enough by now. But as soon as she walked in the door, the looks would start, and they’d be whispering behind her back.

She wasn’t that keen on coming here anyway, but the old priest, Father Brian, was very big on the churches working together. At least that’s what he said. Shirley fancied he was actually keen on getting as much work as possible shifted onto someone else. He was retiring soon. The new priest, Father Joseph, had already arrived. He was a different kettle of fish. He’d preached the sermon last Sunday. All about the devil and the wages of sin. Shirley had a feeling that when Father Joseph took over the parish, there’d be no more mixing with the Protestants. Anyway, today the Young Wives were meeting up with the Methodist Ladies Fellowship for a talk from the new Methodist chap about missions.

The hall was more modern than the room the Young Wives met in, and bigger, with half-peeling lines stuck on the floor for badminton. There was a table laid for morning tea at the far end of the room, and a queue forming by the urn. As Shirley approached, she saw a few swift glances sent her way. She ignored them, and accepted a cup of tea, in a green cup. It was weak. Shirley usually did the teas at St Mary’s. She would never have served up pale brown water, not if they had visitors coming. She found a seat next to Gloria. Gloria had been coming to Young Wives since the fifties. Her daughter-in-law sometimes came now as well. That was fine. So long as Gloria was there, Shirley still counted one of the young ones.

The two groups of women took seats on opposite sides of the hall, eyeing each other cautiously, if not actually with hostility. At the front a tall man in a black shirt and tie was fiddling with a slide projector. Shirley sipped her tea.

One of the women from behind the tea counter came through, wiping her hands on her apron, and whispered something to the man at the front before clearing her throat. ‘Right then. Shall we start with a prayer? Erm… Reverend Price, would you like to lead us?’

There was a pause as the ladies popped their cups down on the floor and bent their heads. Shirley screwed her eyes tight closed. She always did when it was time to pray. Her mother’s voice warning her that the devil came for little girls who looked around still rang in her head. It was nonsense, of course, but the little bubble of darkness made her feel different somehow from the rest of the time, not so much closer to God as simply more distant from the drudgery of normal life.

The priest… no, not priest, vicar maybe? Shirley wasn’t sure. Anyway, whoever he was, he intoned deeply, ‘Let us pray…’

Shirley’s whole body tensed. That voice. It sounded familiar. It dragged her to a time and place a long time ago. 1963. A young girl had taken one stolen moment of excitement in a drab and boring existence. A lad with a teddy-boy quiff when everyone else was growing a mop top had shown her more about life than a single girl ought to know. Then run off and left her no choice but to marry a local lad before she started to show. Shirley screwed her eyes even tighter closed as she remembered her mother’s voice and her father’s fist. Her mother had said Shirley was lucky the Earnshaws hadn’t got wind of her associating with that wrong-un. Lucky Ray Earnshaw didn’t discover the truth until well after the wedding, when it was too late for him to do anything about it. Lucky that Ray valued his reputation enough to say nothing. And lucky he loved the daughter who was his enough to stay.

The voice, that voice that couldn’t possibly be him, was reaching the end of the prayer. ‘Through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.’

All around her the women muttered their amens. Shirley didn’t join in. She had to open her eyes, though. She had to break the little bubble that she’d created when she screwed them closed. It wouldn’t be him. It hadn’t been him when she thought she’d caught a glimpse of him that time they’d gone to Southport when Cathy was a baby. It hadn’t been him when she’d thought she’d seen him in the crowd on Match of the Day. She opened her eyes.

It wasn’t him.

Shirley sat through the whole talk with her handbag perched on her knee, twisting the strap round and round her fingers, trying to listen to what Reverend Price was saying. He was on about sending help to some place she’d never heard of in Africa. A corrupt government was leaving people to starve, the Reverend was saying, when Gloria suddenly shot to her feet.

‘What about our government leaving us to starve>’ Gloria declared. ‘Her. That Margaret Bloody Thatcher. She’ll have the pits closed and us all on the poor house the way she’s going.’

She was surrounded by murmurs of assent. Shirley didn’t bother listening to the churchman’s answer. She was with Gloria. Night after night she’d sit there while Ray went on and on about the state of things. About the unions and the strikes to come. About the need for brotherhood among the workers. Comrades, he called them. Like some bloody commie. And when he wasn’t on about that at home, he was off at some union meeting, leaving her to cope with three kids – one of which wasn’t even hers.

This wasn’t the life she had dreamt about as a girl. She’d been the pretty one. The one they said was going to make a fine match. To live the sort of life others only dreamt about, with a nice home and pretty clothes. And look at her now…

It was suddenly all too much. Shirley got to her feet and walked out of the hall, oblivious to the hubbub behind her. Those woman had been gossiping about her one way or another for most of her life. What did one more day matter?

Shirley didn’t use the shortcut across the stream. She was wearing her Sunday shoes so she walked all the way to the bridge, then turned back along the road to the Heights. She walked past the row of identical terraced houses. There were other women behind those doors, but none of them was her friend. They were, for the most part, tied down with hard work, a baby each year and trying to make ends meet on a miner’s pay.

And the hardest part to accept was that she wasn’t that much different to them.

She turned into Moor Lane and looked up at the house at the end of the terrace. Her steps faltered. There was nothing there calling her home.

She should have loved her firstborn son. Mick was the one thing linking her to those moments of stolen pleasure. But, truth be told, she didn’t love him. In a way, she hated him. If he hadn’t been growing inside her, she never would have married Ray Earnshaw. She certainly didn’t love Ray. Or the daughter she’d given birth to back in the days when she had accepted Ray pawing at her on a Friday night after he’d been down the pub with his mates. And as for that bastard boy – she could barely stand the sight of him.

It occurred to Shirley that maybe she didn’t really know what love was. But one thing she did know was that she had no love for this town, or that house, or any of the people who lived in it.

It made her wonder why she was wasting her life here. She paused. She told herself she could go down to St Mary’s and sit for a while, let the coolness and the quiet of the church calm her. But it wouldn’t work. Eighteen years since she’d had the baby that had tied her to this place and this husband for so long. Five years since Ray had brought that bastard home. She’d put up with more than anyone could expect. She wasn’t going to sit and think and pray and hope to feel better. She wasn’t going to clean and cook and do everything for everyone else.

Something inside her had been pulled taut for too long. And now it had snapped. The girl she’d been all those years ago was awakening inside her and screaming that it wasn’t too late. What Shirley Earnshaw was going to do, was walk back into that cold little house, put her things in a suitcase, get the post-office book Ray knew nothing about from her knicker drawer, and walk away.

Mick pushed his giro cheque over the counter. This was the life – getting paid for doing nothing. It wasn’t much money, but it was more than he’d had before. And it beat working. He was free to do as he pleased. He stuffed the book and money into his pocket and sauntered out into the street. Davo and Spud were leaning on the railings outside the post office. The trio fell into step.

Spud dropped his fag butt to the ground. ‘We getting some beers now then?’

Davo laughed. ‘He’ll have to hand it all over to his dad, won’t he?’

Mick shook his head. ‘No way. I do what I like with what’s mine.’

That was a lie, but he wasn’t letting on. His dad had this idea that now Mick had left school he ought to be paying rent, but that was crap. He couldn’t pay rent because he hadn’t got a job. His dad had plenty to say about that too, but would he help him get one? Not bloody likely. His dad was a supervisor down the pit now. He was a big man. He could’ve got Mick a job if he’d wanted. But no. He said it was up to Mick to make his own way. What was he supposed to do? There weren’t any jobs going outside the pit. At least not for the likes of Mick.

He led the way to the Spar across the road, and picked up a pack of cans. A few years ago, they might have gone to the youth club. But that was closed now. And besides, they weren’t kids any more. They could go to the pub. Spud was still a couple of months short of his eighteenth, but nobody would say anything. Not at the Red Lion. Trouble was, the Lion would be full of his dad’s mates. They’d all be talking about Maggie Thatcher and Arthur Scargill, and the mine and the union and the government. That was all anyone ever talked about. The pit was all that mattered. Some had already closed, and there was talk that they were going to close even more. But the Gimmerton Colliery would never close. It was too big and making too much money.

Mick and his mates made themselves at home on the steps around the statue in the middle of the village and opened the cans.

‘Saw your sister yesterday,’ Spud said. ‘She was up the blue hills with that gyppo kid. What’s his name?’

‘Heathcliff.’ Mick spat out the word as if it was leaving a foul taste on his mouth.

‘Yeah. Him. What sort of a name is that anyway? It doesn’t sound gyppo.’

‘Don’t know. Don’t care,’ Mick said, lighting another fag from the butt end of the first.

Two girls emerged from the Spar. They looked up the hill towards the statue. Mick watched as they exchanged whispers. The blonde one cast a glance his way

‘She’s a bit of all right,’ said Spud, jabbing an elbow in his ribs. ‘You might be in with a chance.’

‘Nah. She’s just a kid.’

‘I dunno,’ laughed Davo. ‘Hey, do you think that gyppo kid and your sister are…’

Mick swung his arm and slapped him up the back of the head.

‘Shut your mouth. That gyppo will never lay a finger on my sister.’

‘Yeah. Sure,’ Davo said quickly. ‘Just saying, they spend a lot of time alone out in them blue hills. Well, we all been up there with girls, haven’t we? You know what goes on.’

Mick crushed his empty can against the statue. Spud kicked his across the square. ‘I’ve gotta get back.’

Mick frowned. Spud never had anywhere to be. ‘Where you going?’

His mate shrugged. ‘Tracy’s mam said I could do a few hours for her on service washes.’

‘Fucking laundry?’

‘Tracy says we have to start saving for baby coming.’

‘Well, bugger off then.’ Mick’s expression closed as his mate strolled away. Spud was trapped. He wasn’t old enough to order a pint in the pub, but he’d got Tracy up the duff and now he had to marry her. He’d have a kid to support. They had no money and were living with her parents. No way Mick was going to end up like that.

Davo chucked his own can against the statue and stood up.

‘You off too?’

‘Well, there’s nowt doing here, is there?’ The clock on the building opposite hit twelve o’clock. ‘Mam’ll have lunch on.’

That was a thought. Mick’s mum would be at one of her church groups, but when she got back she’d do sandwiches with the leftovers from the roast. Mick shrugged. ‘Suit yourself. I’ve got stuff to do too.’

Davo nodded. ‘See you then.’

Mick made his way through town and onto the Heights. It was pretty quiet this time of day. Two of his mates from school had already moved to Manchester to work. One had gone all the way down to London. Some were already working at the pit. A couple of others had gone to college. He saw them every afternoon trudging up from the bus stop at the bottom of the estate at the end of the day. If he ever got away from Gimmerton, he’d never come back. He wasn’t going to end up like his dad, working in the same place every day for forty years, just to pay the mortgage on a terraced house in the Heights. Mick opened the front door and shouted for his mother. There was no answer. He stood at the bottom of the stairs and shouted again. ‘Mum. I want a sandwich.’

No answer. She mustn’t be back yet. He’d have to make his own sandwich. Then he might go up the blue hills. Cathy was a pain but she was his sister. He weren’t going to have people saying his sister was at it with some pikey bastard.

Chapter Five (#ulink_ecc5032e-eee8-5e51-a2c2-54e9cf085622)

April, 1983

Cathy watched the other kids shuffle forward in front of her. She could feel the itching starting at the back of her neck. Her head always itched in the queue. She couldn’t help but imagine the nits crawling through her curls, drinking her blood and laying their eggs in her hair. She thought about it. Had it been itching before she got in the queue? Had it been itching at playtime? Or last night in bed?

She was second from the front now.

‘Hands out of pockets.’ Mrs Bell’s cold voice made her look around. Heathcliff, standing behind her, was the object of the teacher’s glare. She was always telling Heathcliff off. He shrugged his hands down by his side and stared at Cathy.

The queue moved forward. At the front of the line Joanne Warren was having her ginger curls pulled one way and the other by a fat, grumpy-looking woman in a dark-blue dress. Cathy felt her hand rising to scratch the crown of her skull. She stopped herself. Joanne was released by the nurse and the queue moved forward again. Cathy watched Suki Karim unplait her long black hair as she stepped forward. Cathy would be next.

Something jabbed into the small of her back. She spun round. Heathcliff’s grubby finger was still digging into her torso. ‘What?’ she whispered.

He stuck his tongue out at her, rolling it into a tube. She did the same in response. He grinned. It was their secret sign. Mick couldn’t do it and he hated it when they did. Cathy could still see the shadow of the bruises on Heathcliff’s arms where Mick had thumped him yesterday, for doing exactly what he was doing now. Heathcliff never let Mick get him down. Or anyone for that matter. If he could stand up to Mick’s bullying, there was no way a few nits were going to get to Cathy.

‘Catherine Earnshaw!’ Mrs Bell pointed towards the nurse, who had finished her inspection of Suki and was waiting for the next victim.

Cathy stepped into position and turned around, bending her head slightly forward. The nurse smelt of disinfectant and cigarette smoke. She tugged Cathy’s hair apart in sections, and Cathy could feel the woman’s breath on her scalp as she leaned close to make her inspection. ‘All right then.’

Cathy started to walk away.

‘Wait over there for me, pet.’

Cathy stopped. The nurse was pointing towards the corner of shame. Kevin Harrison was already standing there. Kevin Harrison had a black ring around the collar of his school shirt and everyone knew his clothes came out of the charity box at church. Cathy felt tears welling up behind her eyes. She heard a couple of sniggers in the queue. It wasn’t even just her class any more. They’d started to bring the next class in. The whole school would be laughing at her now. They’d be calling her the same names she used to call Kevin Harrison and his sister.

Heathcliff was with the nurse now. He had his head bent forward away from Cathy, but she could see his fist balling up at his side. After a few seconds the nurse released him. ‘Okay. Back to class.’

Heathcliff didn’t move.

‘You’re done, pet. Back to your classroom.’

`Don’t you want me to stand in the corner?’

The kids in the line were interested now. Nobody volunteered to stand in the corner. That wasn’t how the corner worked. The corner was somewhere you got sent. The corner was for the dirty kids, the nitty, infected, outcast kids.

The nurse shook her head. ‘No. You’re fine.’

Heathcliff unclenched his fist, but only for a second before it balled back up again.

‘Heath!’ Cathy hissed his name.

The fist unfurled, and found itself stuffed into his pocket. ‘I’m gonna stand in the corner, miss.’

The nurse shot a look towards Mrs Bell, who shrugged.

‘Fine. Next!’

Heathcliff stood himself next to Cathy and pulled his hand out of his pocket, wrapping his fingers around hers.

‘What are you doing?’ she whispered.

He stared straight into her eyes. ‘Making sure we’re together.’

She didn’t say anything. She didn’t need to. He was right, of course. They were always meant to be together, wherever they were.

Mick lit a cigarette, drawing deeply to make the red flame glow brightly. That should catch their attention. He leaned back against the graffiti-covered wall, doing his best to look cool. He started to hum the new Madness single, and tugged at his jacket the way Suggs did when he sang. Mick took another draw on his cigarette in the way he’d practised in the mirror and ran his hands through his hair. He wouldn’t mind a skinhead cut. But he knew his old man would hit the roof if he did.

The two girls were whispering together, then they looked over at him and saw him watching. They giggled and turned away, arms linked as they scurried home. One of them cast a quick glance over her shoulder. She had curly blonde hair and a really short skirt. She wasn’t as good-looking as that Aussie bird on TV, but Mick thought she was all right. He wouldn’t mind seeing her in a pair of tight black leather pants.

He watched her until she turned the corner, then he pushed himself off the wall. This town sucked. There was nothing to do. It was starting to get dark and a bit cold as he sauntered slowly down the hill towards the creek. He walked along the old fallen tree that spanned the stream without a second thought. Like all the kids from the Heights, he’d been crossing from the town to the estate that way for as long as he had been walking.

On the mine side of the stream, he turned left, towards the pit gates. He could see a gaggle of men standing talking outside the gates – talking strikes, no doubt. The union had just balloted them again, and still not got the result they wanted. His dad was dead against striking, but Mick didn’t agree. If he was ever stupid enough to work there, he’d definitely vote for the chance to take time off.

His dad reckoned it’d get nasty, though, police all over the place and no money coming in. Mick grinned at the idea of coppers trying to keep a bunch of angry miners in check. It’d take more than a truncheon and a stupid helmet to win a fight with the lads from the Heights.

‘Mick!’ His father was one of the men clustered around an oil drum. The miners liked his dad. He was their shift leader. Not a boss – he was one of them. He worked beside them on the coalface. They respected him too, and he was a union rep. He must be a better man down the mines than he was at home. At home, he didn’t say much except to row with Mick’s mum. He always had time for Cathy, of course, and for Heathcliff, but he barely even looked at Mick these days. Maybe here, in front of his friends, his old man would treat him better.

He sauntered over, lighting another cigarette as he did. In his mind he could see his father put an arm around his shoulders and introduce him to the other men as his son, with a tinge of pride in his voice.

‘Where did you get those fags?’ His father’s voice was accompanied by a clip round the back of his head. ‘You been stealing again?’

‘No,’ Mick mumbled as he ducked away.

‘If you’ve been wasting your dole money on beer and fags, I’ll have something to say about it. When you get a job, you can buy fags. In the meantime, you get home and give over that money to your mother. Time you paid for your keep ‘an all.’

Mick mumbled something incoherent, feeling his face redden with embarrassment. How could his father treat him like this in front of the other men? ‘Now you get on home,’ his father said. ‘And tell your mother I might be late. We’ve got union things to sort out.’

There was a murmur of agreement from the nearby men. Sure, they thought his dad was great. They didn’t have to live with him.

As Mick turned away, he heard his father’s voice. ‘He’s always in trouble that one. Time he got a job. There’s nowt for him here.’

‘Me brother works in Manchester. Building trade,’ Mick heard someone say. ‘I can get him to ask around.’

Now that would be the thing, Mick thought as he trudged home. Get out of this bloody dead-end town. There was no way he was ever going down that pit. He wasn’t going to spend the rest of his life covered in sweat and black filth. He was going to make something of himself.

He let the front door bang shut behind him. He thought about going up to his room and forgetting to tell his mother about the food. Serve his dad right to go hungry. But Mick was hungry too, so he sauntered through into the kitchen.

It was empty.

‘Mum!’ he called loudly. Maybe she was in the loo.

He shrugged and opened the bread bin. It was empty. Damn it. His stomach rumbled loudly. The fridge was pretty much empty too. Maybe that’s where his mother was – out getting food. There was one of his dad’s precious cans of Stella in the fridge. Despite what he said in front of the men, his dad always seemed to be able to afford beer. Mick grabbed it and ripped the top off. He took a deep swig, and them almost coughed it all back up again. Rubbing his sleeve across his mouth, he sipped it a bit more slowly as he headed upstairs.

The door to his parents’ room was open. He could see the room was a mess. That was strange. His mum wasn’t the world’s greatest housekeeper, but she was better than that.

‘Mum?’ he called. ‘You there?’

When there was still no answer, he walked into the room and looked around. It was empty. The door of the tatty wooden wardrobe was open, and it was empty. It wasn’t just that his mother wasn’t there; none of her stuff was either. A few wire hangers hung from the rail. Most of the drawers were open too, with nothing inside. Mick swallowed hard. Had they been robbed? Even as he thought it, he knew it didn’t make sense. Burglars didn’t carefully select women’s clothes and leave everything else behind.

He saw something he recognised in an otherwise empty drawer. He pulled it out. It was a scarf – the one he had given his mother for Christmas a couple of years ago. He had saved for weeks to get it for her, and she’d said she loved it. It was bright-red and she’d smiled when she opened the gift, saying it made the place more cheerful.

She was gone. Mick knew it. She’d left him. And she had left his scarf behind.

Clutching the scarf, he left the room and headed into his own bedroom. He wasn’t going to cry. He started to shove the scarf into his bottom drawer, the place where he hid his fags and the dirty magazines Davo stole off his dad. As he did, he happened to glance at the small bundle of belongings on the truckle bed. In the corner of the room. Bloody Heathcliff. Everything had gone to shit since that brat arrived. His mum and dad had barely spoken to each other, and now she was gone. And she’d left Mick behind… Biting back the lump in his throat, he grabbed the sorry bundle of clothes and opened the door. There was no way that little shit was going to sleep here any more. Not after driving his mother away.

He flung Heathcliff’s belongings into the small recessed corner at the top of the stairs. The bed followed. Then Mick walked back into his room and slammed the door. Hard.

‘We’re going to be in trouble,’ Heathcliff declared as they walked back down the path from the blue hills.

‘Nah,’ Cathy said. ‘There’s more trouble down the pit. Always is. Dad spends more time there than at home. And Mum doesn’t care any more. She won’t say anything. She’ll just make us do what the nurse said.’

‘Were they always like that?’

Cathy bit her lips as she tried to remember. There must have been some better times. Maybe before things went bad at the mine. And in the house. She seemed to remember hearing her parents laugh. But not recently.

‘I guess…’ she said hesitantly. ‘What about yours?’

‘There was only ever me and me mam,’ Heathcliff said. ‘And she never laughed much.’