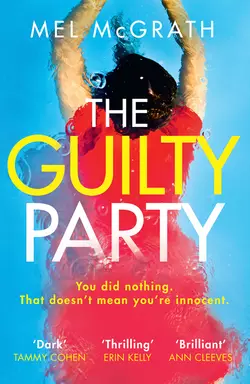

The Guilty Party: A new gripping thriller from the 2018 bestselling author Mel McGrath

The Guilty Party: A new gripping thriller from the 2018 bestselling author Mel McGrath

Mel McGrath

’Dark, thrilling, impossible to predict’ Erin Kelly, author of Sunday Times bestseller He Said She SaidOn a night out, four friends witness a stranger in trouble.They decide to do nothing to help.Later, a body washes up on the banks of the Thames – and the group realises that ignoring the woman has left blood on their hands.But why did each of them refuse to step in? Why did none of them want to be noticed that night? Who is really responsible?And is it possible that the victim was not really a stranger at all?

MEL MCGRATH is an Essex girl, co-founder of Killer Women, and an award-winning writer of fiction and non-fiction.

As MJ McGrath she writes the acclaimed Edie Kiglatuk series of Arctic mysteries, which have been optioned for TV, were twice longlisted for the CWA Gold Dagger, and were Times and Financial Times thrillers of the year. As Melanie McGrath she wrote the critically acclaimed, bestselling memoir Silvertown. As Mel McGrath she is the author of the bestselling psychological thriller Give Me the Child. The Guilty Party is her latest novel.

Copyright (#ulink_47c55b27-9da9-58c1-9329-55a04882e691)

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2019

Copyright © Mel McGrath 2019

Mel McGrath asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © March 2019 ISBN: 9780008217105

This edition 2019/05/07

PRAISE FOR THE GUILTY PARTY (#ulink_e3f5c593-9596-5e96-8ffc-9af180ee40a6)

‘Dark, thrilling, impossible to predict’

ERIN KELLY

‘Brilliant’

ANN CLEEVES

‘Toxic friendship at its worst. Disturbing and dark yet very compelling’

MEL SHERRATT

‘A morally-complex, haunting thriller. The prose is breath-taking. The plot, layered, tense and utterly captivating. If you’re in the market for something sublime, you could not do better than this’

IMRAN MAHMOOD

‘Gripping, haunting, unstoppable. A ruthless and savage page turner’

ROSS ARMSTRONG

‘A dark and immersive journey into the heart of a toxic friendship group and the lies they tell themselves and each other to survive. I loved it’

HARRIET TYCE

‘A psychological tour de force with a superb plot from one of the UK’s most gifted crime writers’

KATE RHODES

‘An intriguing, deftly plotted novel of unravelling friendships and dark secrets’

LIZ NUGENT

‘Honest, dark and searching. I couldn’t put it down’

ALISON JOSEPH

‘Compelling, twisty, thought-provoking, and utterly unputdownable’

ROZ WATKINS

‘Mel McGrath expertly peels back the layers of her characters’ moral self-justification to expose the ugly truth. A scorching, clever thriller’

TAMMY COHEN

For my friends – I promise that none of

these characters are based on you.

There is no greater sorrow than to know another’s secret when you cannot help them.

ANTON CHEKHOV, UNCLE VANYA

Contents

Cover (#uf057936f-4510-5459-a018-3323a038697d)

About the Author (#u1a197780-2910-5a07-9571-c96f987f578f)

Title Page (#uc608c463-f8ed-5472-98b0-4dee5ed6574f)

Copyright (#ulink_fd671519-3c94-5f5c-aa10-24ac2ca1b47d)

PRAISE (#ulink_4e69c4ab-d0f3-5f35-bd8b-9aec28c283d6)

Dedication (#u75652654-ca56-5ab1-83a8-be311f5d632a)

Epigraph (#u487ee467-c428-5b88-bf4f-3fc5ac45f268)

Chapter 1 (#ulink_788c453e-d1d1-54d3-9c30-7b4fc0a4c122)

Chapter 2 (#ulink_317849e5-e066-58ff-94ce-79afe30976b5)

Chapter 3 (#ulink_4a02b9ed-d604-5dea-9f02-38f2e9d7d7ff)

Chapter 4 (#ulink_fe29574d-f5d5-533b-82d0-74623ef7e963)

Chapter 5 (#ulink_6538f95b-4289-5ae2-bda8-90c7131f5060)

Chapter 6 (#ulink_ae56c5a0-ba84-54b4-99de-e493a6a9c412)

Chapter 7 (#ulink_264b9a89-edfb-5ca5-acff-547b3a96fc93)

Chapter 8 (#ulink_57ad266c-ee18-5613-930e-eaacefbcf7f0)

Chapter 9 (#ulink_ac072be9-c431-5dca-bc3c-812ab7154384)

Chapter 10 (#ulink_cdde94a7-86b9-592b-b0b3-5f1d20fe5c26)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 44 (#litres_trial_promo)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1 (#ulink_a29ee68e-4e45-54c7-98b6-0ac7411f94d9)

Cassie

2.30 a.m., Sunday 14 August, Wapping

I’m going to take you back to the summer’s evening near the end of my friendship with Anna, Bo and Dex.

Until that day, the eve of my thirty-second birthday, we had been indivisible; our bond the kind that lasts a lifetime. Afterwards, when everything began to fall apart, I came to understand that the ties between us had always carried the seeds of rottenness and destruction, and that the life we shared was anything but normal. Somewhere in the deep recesses of my mind I think I had probably known this for years, but it took what happened late that night in August for me to begin to be able to put the pieces together. Why had I failed to acknowledge the truth for so long? Was it loneliness, or was I in love with an idea of friendship that I could not bear to let go? Perhaps I was simply a coward? One day, it might become clearer to me. Perhaps it will become clear to you, once I have taken you back there, to that time and that place. And when I am done with the story, when everything has been explained and the secrets are finally out, I will ask you what you would have done. Because that’s what I really want to know.

What would you have done?

Picture this scene: a Sunday morning in the early hours at a music festival in Wapping, East London. Most of the ticket holders have already left, and the organisers are clearing up now – stewards checking the mobile toilets, litter pickers working their grab hooks in the floodlights. Anna, Bo, Dex and I are lying side-by-side on the grass near the main stage, our limbs stiffening from all the dancing, staring at the marble eye of a supermoon and drinking in this late hour of our youth. None of us speaks but we don’t have to. We are wondering how many more hazy early mornings we will spend alone together. How much more dancing will there be? And how soon will it be before nights like these are gone forever?

At last, Bo says, ‘Maybe we should go on to a club or back to yours, Dex. You’re nearest.’

Dex says this won’t work; Gav is back tonight and he’ll kick off about the noise.

We’re all sitting up now, dusting the night from our clothes. In the distance I spot a security guard heading our way. ‘I vote we go to Bo’s. What is it, ten minutes in an Uber?’

Anna has spotted the guard too and jumps onto her feet, rubbing the goosebumps from her arms.

‘I’ve got literally zero booze,’ Bo says. ‘Plus the cleaner didn’t come this week so there’s, like, a bazillion pizza boxes everywhere.’

With one eye on the guard, Anna says, ‘How’s about we all just go home then?’

And that’s exactly what we should have done.

Home. A long night-tube ride to Tottenham and the shitty flat I share with four semi-strangers. The place with the peeling veneer flooring, the mouldy fridge cheese and the toothbrushes lined up on a bathroom shelf rimmed with limescale.

‘Will you guys see out my birthday with one last beer?’

Because it is my birthday, and it’s almost warm, and the supermoon is casting its weird, otherworldly light, and if we walk a few metres to the south the Thames will open up to us and there, overlooking the wonder that is London, there will be a chance for me to forget the bad thing I have done, at least until tomorrow.

At that moment the security guard approaches and asks us to leave the festival grounds.

‘Won’t the pubs be closed?’ asks Anna, as we begin to make our way towards the exit. She wants to go home to her lovely husband and her beautiful baby, and to her perfect house and her dazzling life.

But it’s my birthday, and it’s almost warm, and if Anna calls it a day, there’s a good chance Bo and Dex will too and I will be alone.

‘There’s a corner shop just down the road. I’m buying.’

Anna hesitates for a moment, then relenting, says, ‘Maybe one quick beer, then.’

In my mind I’ve played this moment over and over, sensing, as if I were now looking down on the scene as an observer, the note of desperation in my offer, the urgent desire to block out the drab thump of my guilty conscience. These are things I failed to understand back then. There is so much I didn’t see. And now that I do, it’s too late.

Anna accompanies me and we agree to meet the boys by Wapping Old Stairs, where the alleyway gives onto the river walk, so we can drink our beers against the backdrop of the water. At the shop, I’m careful not to show the cashier or Anna the contents of my bag.

Moments later, we’re back out on the street, and I’m carrying a four pack but, when Anna and I reach the appointed spot, Bo and Dex aren’t there. Thinking they must have walked some short distance along the river path we call and, when there’s no answer, head off after them.

On the walkway, the black chop of the river slaps against the brickwork, but there’s no sign of Bo or Dex.

‘Where did the boys go?’ asks Anna, turning her head and peering along the walkway.

‘They’ll turn up,’ I say, watching the supermoon sliding slowly through a yellow cloud.

‘It’s a bit creepy here,’ Anna says.

‘This is where we said we’d meet, so. . .’

We send texts, we call. When there’s no response we sit on the steps beside the water, drink our beers and swap stories of the evening, doing our best to seem unconcerned, neither wanting to be the first to sound the alarm. After all, we’ve been losing each other on and off all night. Patchy signals, batteries run down, battery packs mislaid, meeting points misunderstood. I tell Anna the boys have probably gone for a piss somewhere. Maybe they’ve bumped into someone we know. Bo is always so casual about these things and Dex takes his cues from Bo. All the same, in some dark corner of my mind a tick-tick of disquiet is beginning to build.

It’s growing cold now and the red hairs on Anna’s arms are tiny soldiers standing to attention.

‘Shall we call it a day?’ she says, giving me one of her fragile smiles.

I sling an arm over her shoulder. ‘Do you want to?’

‘Not really, but you know, we’ve lost the boys and . . . husbands, babies.’

And so we stand up and brushing ourselves down, turn back down the alley towards Wapping High Street, and that’s when it happens. A yelp followed by a shout and the sound of racing feet. Anna’s body tenses. A few feet ahead of us a dozen men burst round the corner into Wapping High Street and come hurtling towards us, some facing front, others sliding crabwise, one eye on whatever’s behind them, clutching bottles, sticks, a piece of drainpipe and bristling with hostility. A blade catches the light of a street lamp. We’re surrounded now by a press of drunk and angry men and women. From somewhere close blue lights begin to flash.

‘We need to get out of here,’ hisses Anna, her skinny hand gripping my arm.

They say a person’s destiny is all just a matter of timing. A single second can change the course of a life. It can make your wildest dreams come true or leave you with questions for which there will never be any answers. What if I had not done what I did earlier that night? And what if, instead of using the excuse of another beer to test the loyalty of my friends and reassure myself that, in spite of what had happened earlier that night, I couldn’t be all bad, I had been less selfish and done what the others wanted and gone home? Would this have changed anything?

‘Come on,’ I say, taking Anna’s hand and with that we jostle our way across the human tide, heading for the north side of the high street but we’re hardly half way across the road when we find ourselves separated by a press of people surging towards the tube. Anna reaches out an arm but is swept forwards away from me. I do my best to follow, ducking and pushing through the throng but it’s no good. The momentum of the crowd pushes me outwards towards the far side of the road. The last I see of Anna she is making a phone sign with her hand, then I am alone, hemmed in on one side by a group of staggering drunks and on the other by a blank wall far too high to attempt to scale.

Moments later, the crowd gives a great heave, a space opens up ahead and I dive into it, ducking under arms and sliding between backs and bellies and a few moments later find myself out of the crush and at the gates of St John’s churchyard, light-headed, bruised and with my right hand aching from where I’ve clutched at my bag, but otherwise unhurt. I feel for my phone and, checking to make sure no one’s looking, use the phone torch to check inside the bag. In my head I am making a bargain with God. Let me get out of here and I will try harder to believe in you. Also, I will find a way to make right what I have done. Not now, not right away, but soon. Now I just want to get home.

The light falters and in its place a low battery message glows. God’s not listening and there’s nothing from the others. I tap out a group text, where r u?, and set myself to the task of getting out.

Taking the path through the churchyard, feeling my way past gravestones long since orphaned from their plots, I head along a thin, uneven stone path snaking between outbuildings at the back of the church. From the street are coming the sounds of disorder. Somewhere out of view a mischief moon is shining, but here the ground is beyond the reach of all but an echo of its borrowed light and it’s as quiet as the grave.

The instant my heart begins to slow there’s a quickening in the air behind me and in that nanosecond rises a sickening sense that I’m not alone. I dare not turn but I cannot run. My belly spasms with an empty heave then I am frozen. Does someone know what I’ve got? Have they come to claim it? What should I do, fight for it or let it go?

A voice cuts through the dark.

‘Cassie, darling, is that you?’

There’s a sudden, intense flare of relief. Spinning on my heels, I wait for Anna to catch me up. ‘Oh I’m so glad.’ She flings an arm around my shoulders and for a moment we hug until the buckle of my bag digs into my belly and I pull away. What a shitty birthday this has turned out to be. If they knew what I’d done some people would say it’s kismet or karma and if this is the extent of it I’ve got off lightly. They’d be right.

‘Have you seen the others?’ I ask Anna.

‘Bo was with me for a bit. He and Dex got caught up in the crowd which was why they didn’t make it to the Old Stairs, then they got separated. No idea where Dex is now. He might have texted me back, but my phone’s croaked.’

‘I got nothing from him either.’

‘You think we can get out that way?’ She points into the murk. ‘Hope so.’

We pick our way down the pathway into the thick black air beside the outbuildings, me in front and Anna following on. As we’re approaching the alleyway between the buildings my eye is drawn to something moving in the shadows. A fox or a cat maybe? No, no, too big for that. Way, way too big.

I’ve stopped walking now and Anna is standing right behind me, breathing down my neck. Has she sensed it too? I turn to see her pointing not to the alley but to the railings on the far side of the outbuildings.

‘Anna?’

‘Thank God!’ She begins waving. ‘The boys have found us – look, over there.’ In the dim light two figures, their forms indistinct, are breaking from the crowd and appear to be making their way towards us.

‘Are you sure it’s them?’

‘Yes, I can tell by way they’re moving. That’s Dex in front and Bo’s just behind him.’

I watch them for a moment until a group of revellers passes by and the two men are lost from view. From the alley there comes a sudden cry. Spinning round I can now see, silhouetted against the dim light of a distant street lamp, a man and a woman. The man is standing and the woman is bent over with her hands pressed up against the wall, her head bowed, as if she’s struggling to stay upright. I glance at Anna but she’s still looking the other way. Has she seen this? I pull on her arm and she wheels towards me.

‘Over there, in that alley.’ It takes a moment for Anna to register, a few seconds when there is just a crumpled kind of bemusement on her face and then alarm. The man has one arm around the woman’s waist and he’s holding her hair. The woman is upright now but barely, her head bowed as if she’s about to throw up.

Anna and I exchange anxious looks.

Every act of violence creates an orbit of chaotic energy around itself, a force beyond language or the ordinary realm of the senses. A gathering of dark matter. The animal self can detect it before anything is seen or heard or smelled or touched. This is what Anna and I are sensing now. There is something wayward happening in that alley and its dark presence is heading out to meet us.

With one hand the man is pressing the woman’s face into the wall while, with the other, he is scrabbling at her clothes. She is as floppy as a rag doll. He has her skirt lifted now, the fabric bunched up around her waist at the back. Her left arm comes out and windmills briefly in the air in protest. Her hand catches the scarf around her neck and there’s a flash of yellow and blue pom-poms before the man makes a grab for her elbow and forces the arm behind her back. The woman stumbles but as she goes down he hauls her up by her hair. Her cry is like the sound of an old record played at half speed.

Something is screaming in my head. But I’m pushing it away. Another voice inside me is saying, this is not what I think it is, this is not what I don’t want it to be, this is not real.

The man has let go of the woman’s hair. He’s pressing her face into the wall with his left hand while his right hand fumbles at his trousers. His knee is in the small of the woman’s back pinning her to the wall. The woman is reaching around with her arm trying and failing to push him away but her movements are like a crash test dummy at the moment of impact.

‘Oh God,’ Anna says, grabbing my arm and squeezing hard, her voice high-pitched and tremulous.

In my mind a furious wave is rising, flecked with swirling white foam, and in the alley the man’s pelvis is grinding, grinding, slamming the woman into the wall. The world has shrunk into a single terrible moment, an even horizon of infinite gravity and weight, from which there is no running away. Anna and I are no longer casual observers. We have just become witnesses.

I feel myself take a step forward. My legs know what I should be doing. My body is acting as my conscience. The step becomes a spring and Anna too is lunging forward and for a moment I think she’s on the same mission as me until her hand lands on my shoulder and I feel a yanking on the strap of my bag and in that instant, Anna comes to an abrupt stop, sending the bag flying into the air. It lands a foot or two away and breaks open, its contents scattering. The shock soon gives way to a rising panic about what might have spilled and I’m down on my knees, rooting around in the murk, scraping tissues and lip balm, my travel card and phone, cash and everything else back inside the bag, checking over my shoulder to make sure Anna hasn’t looked too closely at the spilled contents.

As I rise she’s grabbing my wrist and squeezing the spot where my new tattoo sits. I try to shake her off but she’s hissing at me now, her body poised to pull me back again. ‘Don’t be so bloody stupid! You don’t know what you’re getting into.’

‘He’s hurting her! Someone needs to intervene. At least let’s call the police.’

My hand makes contact with my bag, peels open the zip and fumbles around in the mess. And in that moment in my mind a wave crests and rushes to the shore and the foam pulls back exposing a small bright pebble of clarity. What would the police say if they found what I am carrying? What would Anna say?

In my mind an ugly calm descends. My hand withdraws and pulls the zip tight. They say that it’s in moments of crisis that we reveal most about ourselves.

‘My battery’s dead. You’ll have to call from yours.’

I’d like to say I’d forgotten that Anna’s phone was out of juice but I hadn’t. In any case, Anna isn’t listening. Something else has caught her attention. On the far side a phone torch shines, a light at the end of a dark tunnel, and in its beam is Dex, as frozen as a waxwork. Behind him, in the gloom, lurks a shadowy figure that can only be Bo. If anyone is going to put a stop to what is going on in the alley it’ll be Bo.

Won’t it?

‘Please,’ murmurs Anna. ‘Please, boys, no heroics.’

Dex continues to stand on the other side of the alley, immobile, his gaze fixed on me and Anna. It’s at that moment that I become conscious of Anna shaking her head and Dex acknowledging her with a single nod. For a fraction of a second everything seems frozen. Even the man, ramming himself into the woman in the alley. And in that moment of stillness, an instant when nothing moves.

We all know what we are seeing here but in those few seconds and without exchanging a word, we make the fateful, collective decision to close our eyes and turn our backs to it. No one will intervene and no one will tell. The police will not be called. The woman will be left to her fate. From now on, we will do our best to pretend that something else was happening at this time on this night in this alley behind this church in Wapping. We’ll make excuses. We’ll tell each other that the woman brought it on herself. Privately, we’ll convince ourselves that this can’t be a betrayal because you can’t betray a person you don’t know. We will twist the truth to our own ends and if all else fails, we will deny it.

We’ll do nothing. But doing nothing doesn’t make you innocent.

The light at the end of the tunnel snaps off and in a blink Dex and the shadowy figure of Bo have disappeared into the darkness. I look at Anna. She looks back at me, gives a tiny nod, then turns and begins to hurry away up the path towards the church. And all of a sudden I find myself running, past the alley where only the woman remains, slumped against the wall, past the wheelie bins, along the side of the church, between tombstones decked in yellow moonlight and out, finally, into the street.

2 (#ulink_77708a85-3b3e-59d8-85a8-e76296aa19b9)

Cassie

6 p.m., Thursday 29 September, Dorset

As the train is pulling into Weymouth a text comes through. So soz, darling, held up, take cab, followed by the address and postcode of the holiday cottage. Not the best of welcomes, but never mind. We’re at the start of a lovely extended weekend, just the four of us, and that’s such a rare event these days, life and careers being what they are, and husbands and babies being what they are. Four whole days in the company of your best friends. Your only real friends.

At the station, a fellow passenger helps me lift my case from the carriage onto the platform. It was cold and drizzly when I left London and it’s more or less the same now, only colder, and naturally, me being me, I’m wearing the wrong jumper for it, but never mind. I’ll find something warmer in the case when I reach the cottage. The bag is heavy with new clothes, new shoes, the results of a rare online spending spree. This weekend I’m intending to dress to impress. If anyone asks where I got the money (and they will) I’ll say I got promoted at the school, something more of a hope than a reality.

The driver slings my bag into the boot of the taxi while I let myself inside. A taxi is fine.

‘You been to the island before?’ the taxi driver says, when I show him the text containing the address.

‘No. Is it nice?’

‘If prisons and quarries are nice,’ he responds, drily.

‘We’re celebrating my friend Bo’s birthday. He used to come here with his dad to collect fossils. It’s his shout.’ Jonathan Bowman was a City lawyer with a passion for palaeontology and a rocky heart that gave out at fifty-six. None of us thought the fact that Bo went on to study the subject at uni was anything but the prince looking for the king’s approval. I have wondered more than once whether this trip is an act of reconciliation, a reckoning of the past as well as a means of reinventing it. Not that Bo, who has never been one for introspection, would ever put it that way.

‘If you ask me, you’d be better off in Weymouth. We got a TGI Fridays,’ the taxi driver says, pulling from the station drop-off into the traffic.

As the taxi makes its way through the scrappy splendour of central Weymouth into nondescript suburbs I’m caught up in the anticipation of it all. Four days. No partners or babies or distractions. It’ll be just like old times. After all that happened at the Wapping Festival, this is what we need.

The road narrows onto Chesil Spit. To our right stretches the long, thin finger of Chesil Beach, empty now save for a few gulls, to the left is a huddle of industrial-looking buildings set on an expanse of what looks like wasteland. The driver explains this was the old naval base where the 2012 Olympic water sports were staged. Then, all of a sudden, we are on the Isle of Portland.

‘Why do they call it an island?’

The taxi driver’s eyes flit to the rear-view mirror. ‘I’ve never asked.’

We sail past an old boozer, an ad outside reading, ‘Wanted: New Customers’, over a mini-roundabout and left up a steep hill on the top of which perches what looks like an ancient fort.

‘The Citadel,’ volunteers the driver, observing my gaze. ‘It was originally a prison for convicts waiting to be transported to Australia. It’s a detention centre for refugees now. Nothing’s changed.’ He lets out a grim laugh. ‘There’s another prison in the middle of the island. Young offenders mostly, that one. I get a lot of business from that prison. Mums visiting, that kind of thing. There’s a bus from the mainland but it doesn’t drop off or pick up at visiting hours. Crazy, innit, but that’s Portland. Nothing here makes much sense.’

Above the roof line, beside a ragged buff, a fistful of raptors swoops and hovers in a beautiful, sinister choreography. The taxi driver says he has no idea what they are. Hawks? Kestrels?

‘They do that when they’re hunting.’

He turns off the main road onto a tiny unpaved lane. We climb steeply through low, wind-burned shrubs in silence, wrapped in our own worlds. Halfway up the hill the driver makes a sharp right into a driveway surrounded by wind-breaking hedges and suddenly, as if rising from the murk, a large cottage of ancient brick with a mossy slate roof appears and a voice on the GPS announces that we have reached our destination.

The driver pulls up behind a silver BMW and a midnight blue Audi coupé and I use the time it takes for him to go round to the boot to fetch my bag to take in the scene. The air is clean and carries a tang of seaweed and moss and even now, before sunset, it’s cold and raw in the way London never is. The cottage itself is Georgian or maybe early Victorian, built for a time long gone when keeping out the elements was more important than bringing in the light. A creeper whose leaves are already turning curls around tiny, squinting windows untroubled by the sun and gives the place a forlorn and slightly malevolent air. It’s beautiful in the way that dying and melancholy things are beautiful.

‘Right then,’ says the driver, depositing my bag on the gravel drive. He mentions the fare, a sum that only a month or so ago would have sent me into a spin but now feels perfectly manageable. I reach for my bag and pull out my purse. How lovely to be able to be so casual about money. This must be how the others feel all the time.

At that moment the front door swings open and Anna appears and comes towards me, arms outstretched. ‘Darling. Look at you!’ she says, flashing her wide, breezy, Julia Roberts smile and wrapping me in a hug before pulling away to pluck at the collar of my cherry-red blouse. ‘Such a good colour on you. But then you’ve always been so brilliant at picking out the charity shop bargains.’

Anna herself looks radiant. Anna is always radiant. And thin. And secretly unhappy. She checks my bag. ‘Such a practical bag. I’ve brought all the wrong things. Of course. I’m so sorry we couldn’t pick you up. Bo’s new car.’ She waves in the direction of the Audi. ‘Some enginey widget went wrong and we had to sit in the garage until the mechanic had fixed it. Bo’s being a bit boring about it, tbh, but it’s his birthday weekend so we all have to find something nice to say.’

Beside us, the taxi driver hovers for his money. A mariner’s lamp flickers on in the porch and Bo appears, dressed in smart casuals draped expensively over a treadmill-lean body.

As I open my purse Anna reaches out a staying hand.

‘Oh, don’t worry about that. Bo will sort it out.’ Anna turns her head and flashes Bo a smile. ‘You’ll bring in Cassie’s bag and deal with the fare, won’t you, darling?’

‘Of course.’ Bo slings an arm around my shoulder and drops a kiss on my head. ‘Welcome to Fossil Cottage, Casspot.’

‘Top wheels.’

Bo eye-rolls. ‘I know you couldn’t care less, but sweet of you to play along. I’m trying not to go on about her but first flush of love and all that. Once we’ve had a few bevs, and I’m wanking on about the multi-collision brake assist function, which I guarantee you I will be, please feel free to tell me to shut the fuck up.’

‘You never bore us, Bo darling, does he, Cassie?’ Anna says, looking to me for confirmation.

‘There’s always a first time.’

Bo laughs and tips me a wink. Anna and I move across the mossy gravel drive towards the front porch leaving Bo to sort out the taxi driver and my bag.

‘Isn’t this heavenly?’ Anna says, meaning the cottage. ‘As soon as I saw it on the website I thought: yes. It’s got a kind of Rebecca meets Wuthering Heights with a Paranormal Activity vibe, don’t you think? Wait till you see inside. You’re going to love it. We’ve given you the bedroom at the top of the house.’

‘The mad woman in the attic spot.’

Anna’s left eye flickers and for a moment she searches my face. ‘Oh I see, yes. Funny you!’ We’re almost at the front porch now. ‘So listen, Dex is in the kitchen sorting out supper. We’re having roast chicken.’

‘My favourite.’

Later, Anna will push whatever Dex cooks around on a plate before hiding it under her cutlery. But for now, she steps jauntily around a large stone carving of what appears to be a cockerel with the tail of a fish.

‘Some Portland thing called a Mer-chicken, Bo says. But maybe he was joking. It’s not always obvious with Bo, is it? Don’t worry, it won’t bite.’ Her voice softens to a whisper. ‘Gav’s here, though, and he might. He gave Dex a lift and they must have had a row on the way because he’s in a terrible grump. Thank heaven he’s not staying, but he wanted to say hello to you before driving on to Exeter to have dinner with his sister.’ She holds the door and waves me through a hallway lined with worn stone flags smelling of new paint in a Farrow and Ball drab.

‘Seems ages since we last did something like this,’ Anna says, directing me to a row of Shaker style coat pegs.

‘Wapping Festival was only a month ago.’ From the corner of my eye I see Anna stiffen.

‘I meant the last time we were together for a whole weekend. Bestival, wasn’t it? Do you remember that Bo threw a strop because that glamping yurt cost him a fortune and it was bloody freezing.’

As I recall it was Anna who threw the strop, but Anna has a habit of reinventing things.

‘I remember the rain and that amazing fluorescent candy floss.’

‘Oh yes, yum,’ says Anna.

We enter the hallway and move into a large kitchen done out boho country style, where Gav is sitting in a bentwood chair at an enormous old pine kitchen table, dressed in the full upper middle class fifty-something Londoner’s idea of country garb, cords and an Aran with a jaunty silk neckerchief tucked beneath to signal both his class and sexual preference, and fiddling with his phone. An expensive-looking wax jacket hangs over the chair. Behind him Dex is smearing butter over a large prepared chicken. A whisky bottle sits on the table and the room smells warm and peaty but there’s a palpable tension in the air.

‘No bloody signal!’ Gav looks up, sees me and manages a smile. ‘Oh, hello there, dear Cassie. Give this old man a hug and he’ll be on his way.’

Gav has always been a huge, beary barrel of a man but the weight loss in the six months since I last saw him is shocking and not altogether flattering. It makes him seem much older and a bit clapped out.

Dex turns and holding two buttery hands in the air, whoops a greeting, then Bo appears carrying a rolled-up newspaper.

‘I’ve put your bag in the hallway, Casspot. The driver said you left this?’ He slaps a copy of the Evening Standard on the table.

‘Not mine, but never mind.’

‘Why don’t I show you to your room?’ Dex says. The chicken has gone in the oven and he’s now washing his hands in the kitchen sink.

We clamber up a steep flight of stone steps with a grab rope on one side onto the first-floor landing off which come three bedrooms and a bathroom. Above each room hangs a fossil, or, more likely, a reproduction of a fossil.

‘Anna allocated the rooms. She thought it would be funny to give everyone the room with the fossil that was most like them, so that one’s Bo’s.’ Dex points to a panelled door at the end of the corridor above which sits what looks like a large elongated snail. ‘Guess.’

‘I don’t know. Leaves a trail of slime behind him?’

Dex’s eyes crease with mirth. ‘That’s what I said too. Wrong though. Apparently it’s called a Portland Screw.’

‘Boom tish.’

‘You have to admit it’s good though. Bo once told me that sex was the only contact sport where he’d played all the known positions.’

‘Funny man. What’s yours?’

‘Oh, my room is named after some kind of fossil oyster called a Devil’s Toenail,’ Dex says, gesturing at a closed door beside the bathroom. ‘Anna thought that was hilaire. Her room is the one at the end. That thing with all the arms is called a Brittle Star.’ He turns and smiles. ‘No one can accuse Anna of not being able to take the piss out of herself.’

And with that we proceed up another, even narrower and more steeply inclined staircase, onto a small landing.

‘Yours is the Urchin room. Tiny, but so are you. You’re the only one with a direct view over Chesil Beach and you’ve got a shower to yourself so we thought you wouldn’t mind.’ Dex opens the door with a flourish. ‘Ta da.’

The room is just large enough to hold a double mattress and a few stylish cushions. A stool doubles up as a bedside table. Through a small window comes the thick smell of brine and the sound of the waves on the shingle. The lights of Fortuneswell wink.

‘It’s brilliant.’

‘Oh good, well, I’ll let you settle in.’ Dex turns to walk away but hesitates by the door, waiting for me to address the elephant in the room. Though there are two, really: Gav’s weight loss and what happened a month ago at the festival.

‘Is Gav OK?’

‘He’s in a sulk, is all. He’s got it into his head that someone took some money from the house. It’s bullshit. He’s just forgotten where he left it.’

‘I meant his weight.’

Dex is hovering with one foot outside the door. He doesn’t like talking about difficult stuff. Never has. When we split up, all those years ago, he took me out for a drink in a very noisy bar, waited until Michael Jackson was working his way through the first chorus of ‘Billie Jean’ on the PA system, and, evidently imagining his moment had come, blurted, ‘I seem to have fallen in love with a man,’ and that was that. Four years as a couple. Game over.

Back then he screwed his eyes tight so as not to witness my distress and he’s doing the same now. He says, ‘Gav’s got pancreatic cancer. It’s pretty advanced. We got confirmation a couple of weeks ago and a couple of days later he was having his first chemo. That’s why he’s going to see his sister, break the news. He’s bloody angry about it.’

‘Is it . . .’

‘Terminal?’

‘I wasn’t going to say that.’

‘But you were thinking it, weren’t you?’ There’s an accusatory note in his voice. ‘Yes, probably.’

When I make a move towards him he backs off a little, unable to be comforted.

‘I’m sorry.’ I really am. Even though he stole Dex from me, I don’t wish anything nearly as final as death on Gav. A little bad luck, maybe, but this, no. Way too much.

‘To be honest, I just want to be able to forget about real life for a couple of days and try to enjoy the break. Have you seen much of the island yet? Not the most obvious spot for a birthday weekend, but at least it’s not dull.’ He softens the corners of his mouth. ‘I should go down and see Gav off, get back to the cooking.’

I wait for him to disappear before drawing the curtains and taking a quick shower, then sit for a moment trying to absorb the news about Gav. If there was a time to bring up what happened in Wapping, this isn’t it. Then putting on my game face, I make my way to the ground floor.

At some point, the owners of the cottage have knocked down a few walls to create a semi open-plan living room cum kitchen. Anna has the oven door open and is peering at the chicken, Bo is setting a fire in the grate in the living room. A bottle of red stands aerating on the kitchen table beside Dex who is sitting at the table with his chin in his one hand, looking pensive. Gav appears to have left.

‘Oh, darling, did you like your room?’ Anna says, swivelling to look at me.

‘Is Gav gone?’

‘Only just. You’ll catch him if you’re quick,’ she adds, with a tilt of the head and a press of the lips to let me know that she too has heard the news.

I run outside, crunching across the gravel and waving madly. Gav is sitting in the BMW adjusting the heating and looking very old and very, very alone. The driver’s side window whines open and before I’ve opened my mouth he cuts me off with, ‘No outpourings, please. It is what it is.’

‘Can I at least say I’m sorry?’ He pauses, as if considering this. To my surprise, because Gav is nothing if not old school, his eyes go filmy. ‘What you can do is be good to Dex. I’m scared I won’t be around for him.’

‘Done.’

‘Another thing. That festival business, with the woman?’ His rheumy eyes fix on mine. ‘I think I should tell you that he is in a lot of trouble about what happened. He thinks he isn’t, but he is.’

I feel myself slump back. What trouble could he possibly be in?

‘I see he hasn’t spoken to you,’ Gav says, drily, registering the shock on my face. ‘Well, since you’re probably closer to Dex than anyone other than me I should probably tell you: the police came round.’

I nod calmly, but my mind is racing. There was that scrap Dex got into at the festival . . . Anna said it started over some drunk accusing him of looking at his girlfriend, but it didn’t amount to anything. Surely the police wouldn’t come round for that?

‘Don’t tell him I let the cat out of the bag, please, or mention it to the others. He’d kill me. Solemn promise?’

‘Yup.’

‘In the scheme of things, really . . .’

‘I understand.’

Gav blinks a thank you and the car window begins to whir to the vertical. He waves and turns the steering wheel and the BMW crunches across the gravel and disappears from view.

3 (#ulink_845d2184-cec2-58b9-8e37-80fed830f39e)

Anna

7 a.m., Sunday 14 August, Royal London Hospital

When Dex finally emerges from the cubicle in Minors, Anna has been calming herself with some mindful belly breathing exercises for over half an hour and is able to greet him with what she hopes is her normal face.

Since the events of earlier – she’ll say events because it makes what they saw seem less real – she’s been a bit of a mess. Can’t get her mind to engage. Something inside her head is making a sound like a slipped gearbox. The whole evening feels like an odd dream, although she is wide awake and as sober as a judge now. She’ll wake up tomorrow hung-over and wonder if any of it really happened.

Dex is still drunk. She can tell by the way he’s walking towards her. That’s good too. The more everyone’s mind is scrambled the easier it will be for all of them to get through this. Dex is unlikely to remember many of the details. Bo might but he’s less easily shaken than the others. Cassie will do whatever Dex does. Anyway, the worst has been averted. She rises from the plastic chair in the waiting area and spots on the seat beside her a small still wet nugget of gum. Shaking off her disgust, she sets her mouth into a smile and waits, arms outstretched, for Dex to approach.

‘Dex, darling, ouch, oh poor you.’ A bandage is wound over the right fist, a plaster on the right cheek, right eye as burst as a stewed plum. She leans up and plants a kiss on his lips. He gives her his forlorn look. A bit little boy lost.

‘You should see the other guy,’ he says, playing hanging tough. He means the guy at the festival, of course. Some arsehole over by the beer tent, apparently. You looking at my girlfriend? As if. Anna had noticed his war wounds as soon as Dex had got back to the main stage earlier but, honestly, it hadn’t looked particularly bad. Now it’s been a few hours and the injury has had time to swell and fester.

‘Is Bo still in there?’ she asks.

‘I guess so. He got called just before me, but maybe he’s had to have an x-ray or something.’

‘He’s not badly hurt, is he?’ Not long after what happened in the alley Anna had received a message from Dex to say that Bo, too, had got into a skirmish – this time with a couple of guys, something to do with a spilt beer, and they were going to A&E to get him sorted.

‘He’ll live. Where’s Cass? I thought she’d be with you.’ Dex checks his phone and runs a hand over bedraggled hair.

‘We got separated in the churchyard. My phone’s croaked. She’s probably back home by now though. What a horrid birthday celebration it’s turned out to be, poor darling.’

Dex cocks his head, presses his lips together and nods at the truth of this. He’s so easily placated, so much less demanding than Bo. She watches him frown then peer at her neck.

‘That looks like a nasty bruise.’

Anna taps the dark spot then dismisses it with a wave of her left hand. ‘Oh, it’s nothing, darling, I got shoved in that scrum. To be honest I’m more pissed off about my jumpsuit.’ She points to the tears in the fabric, pre-empting any awkward questions. ‘Speaking of, what happened in the churchyard?’

Dex closes his eyes, trying to summon a memory, opens them again and blinks. ‘Oh, you mean that couple?’

‘Is that what they were?’

‘What I saw, a couple of randos having a quickie.’ He seems anxious to change the subject. Good, thinks Anna. In that case, he’ll be cooperative. ‘I thought that arsehole was about to come at me so I decided to take off.’

This is not how Anna remembers it. What Anna recalls is that Dex switched off his phone light and ran away into the night, leaving the woman in the alleyway to her fate. Lowering her voice, Anna says, ‘I honestly don’t think we should talk about it any more, darling. Why get involved? God, it’s a madhouse in here. Let’s find somewhere else to sit.’ She picks up the Diet Coke she left as a placeholder and holds it out to Dex. There’s nothing she wants more than to put this whole awful night to bed. ‘You want some?’

‘Thanks.’

While Dex drains the can, Anna scouts for a more genial spot to wait, not easy in a London A&E during the early hours of a Sunday morning. The place is a heaving mosh pit of drunks and wasters, most, by the looks of them, walking wounded from the fight that kicked off after the festival. A name is called and one of the anxious parents stands up and offers a hand to his son, leaving a couple of plastic chairs empty near the triage station. Anna points and lets Dex lead.

A nurse glides by, smiling, followed by two policemen. All three disappear through swing doors into another part of the hospital. Anna jams her hands in her lap and watches them go with mounting relief. They’ll have other things on their minds. ‘Want another Coke, darling?’

‘Not really.’

The guy opposite is doing his best to remove an Egg McMuffin from its paper bag with one hand. A sickening, sulphurous smell drifts over. Anna flaps her hand and wrinkles her nose. The Egg McMuffin guy gets up and obligingly moves off. A moment later the swing doors part and the two coppers reappear. Anna sits on her hands while they go past. A nurse walks by. A man’s name is called. The Egg McMuffin guy sinks into a more distant chair.

‘When did you get here?’ Anna says. She needs to be careful about the timeline. Doesn’t want to get caught out.

Dex checks his watch. ‘Ages ago. Not sure, to be honest. They kept me waiting in the cubicle for what seemed like forever. Man, I’m wrecked.’

At that moment a figure emerges from behind the swing doors, eyes unfocused, a bit staggery, evidently still high, a couple of nasty-looking abrasions on his face and a puffy nose. Anna feels herself stiffen then soften then stiffen and then, putting her feelings aside, rises up and goes towards him, with Dex following on behind.

‘That looks sore.’ In the circumstances, it hurts her to have to take him in her arms and give him a hug but it’s necessary. Men have to be managed. His body is electric and uncoordinated, like a cheap firework display. He doesn’t notice the bruise on her neck.

‘I’m fine,’ he says, shrugging her off. His pupils are a single grain of lumpfish roe floating on a tissue of blood. What the hell has he taken this time? Whatever it is, the nurse has discharged him so it’s clearly not life-threatening, thank God. ‘Nurse said some bastard must have gone at me with their house keys. I don’t know about you lot, but I need a fry-up.’

‘You need to go home, like now,’ Anna says. She throws him a steady look which he returns, very briefly, the only focus he can manage right now. He’s understood her, though. He’s picked up something serious in the tone. ‘Make sure he gets to bed, Dex, won’t you? I have to get back for Ralphie,’ Anna says.

Slowly, they lead Bo through the corridor towards the exit. As they pass the lifts, the doors open and the two coppers appear from within, solemn-faced, as if they’ve just come from dealing with some hard business. Anna looks away. Thank God they’re about to be rid of the stale air, the smell of vomit and egg and antiseptic, the tang of fear and adrenaline. What an unspeakably difficult night. She’s within whispering distance of being able to put it all behind her. This night, at least. There might be repercussions, though, God knows. But she’ll think about that later. She’s exhausted, at breaking point. If only she could just run home to her parents. If only she had the kind of parents you could run home to. Hers would only make everything worse. Mummy would find a way to make it all about her and Daddy would dump her off on her stepmother.

‘Ordering the Uber right now,’ Dex says, pulling his phone from his pocket.

Anna leans against the retaining wall of the municipal flower bed beside the entrance and waits with them, overwhelmed by the effort of seeming so normal when she’s feeling as if she might at any moment crack open and the separate pieces of her heart fly out into what remains of the night.

‘Anna, gorgeous girl, you’re shaking!’

She brushes this off with a smile. Why does it always have to be Dex who notices these things? ‘Just tired.’

The cab arrives and takes the problem back to the flat with the river view from where he came. And oh, the relief! The instant the vehicle is out of sight her legs go from under her and she has to sit back against the flower bed and recompose herself.

She takes a deep breath and holds it until her face feels as if it might explode then lets it out in one, in the hope that it might take all the guilt and the trauma of the night with it. Adjusting her jumpsuit and smoothing her hair she goes back through the hospital swing doors and picks up the taxi phone.

A voice asks, ‘Where to?’

Home, she thinks. Back to Ralphie.

4 (#ulink_4c107780-e395-58f7-aff2-04ff58c189b6)

Cassie

6.05 p.m., Thursday 29 September, Dorset

Within minutes of my arrival at the cottage, we have settled back into our habitual routines. Dex, the entertainer, is telling one of his bad jokes; Anna, the doer, is rifling through cupboards looking for box games and, even though there’s no signal, Bo, the bystander, is scrolling idly through his phone. And I am sitting at the kitchen table observing all this, beside me a bottle of wine, more than half empty now, and the discarded copy of the Standard, reminding me of all those years, before I gave up on myself, when I would grab a copy at the tube on my way home from teaching and look forward to sitting down with a glass of wine and unwinding with the crossword. And now? Why not?

‘Anyone got a pen?’

‘There’s one in that pot there, by the sink,’ Anna says, as if it’s something she has always known. Of the four of us, Anna has always been the most observant and the tidiest, the pickiest eater, the most careful driver, the girl in control, the subject of male admiration and female envy. It was Anna who introduced me to Dex. She was in my seminar group but it was months before I plucked up the courage so much as to smile at her. Anna was both posh and cool, which was rare at Oxford, where the cool set and the posh set didn’t often intersect. She had a smartphone then, in 2006, which was the hippest thing I’d ever seen. I would overhear her talking about people she knew who had parts in Harry Potter films, people who went snowboarding in Aspen and went to Glastonbury on ‘access all area’ passes. She wore tiny shorts and minis with Uggs and she had all this hair which she wore long with a fringe half obscuring her eyes. In Oxford, where it rains all the time, I never once saw her look anything but perfectly groomed. And of course she lived out of college, in a house in Jericho, which was where all the cool students had rooms and her housemates were all DJs and part-time games designers.

To a girl like me, who’d grown up on an estate in a dreary commuter belt town at the end of the Metropolitan Line, with a mother who drank and served family sized packs of Wotsits for tea and a father who pretended to go to his job at the council every day for six months after he’d been sacked, Anna seemed to have come from another planet. From the moment I first saw her in my seminar group I was half in love with her. I still am.

As for what Anna saw in me? A certain kind of naïve intelligence perhaps. A willingness to please. Early on I had given up on understanding people, who were beyond me. Instead I had made myself a quick study of the material business of the world. By the time I was ten I knew the names of thirty-seven species of migratory birds and could name all the capitals of the world. Facts were the barricades behind which I retreated from Mum’s alcoholism and Dad’s weirdness. People-pleasing was the Technicolor coat I wore to disguise the drabness of my surroundings. Soon I became good at being able to absorb, even to take on, the self-serving lies of others, and pretend they were true. I knew my dad wasn’t really going to work every morning and I knew my mother was keeping vodka miniatures buried in the cat’s kibble long after she swore she’d given up. I never confronted them because I knew it wouldn’t change anything and would probably make all of us even unhappier. Perhaps it’s this that Anna sensed in me. She knew I would never challenge her. So long as she and I were friends, Anna would always be the Group’s number one girl.

‘You’re not going to do crosswords all weekend, are you, darling?’ she asks me now, one eyebrow raised.

‘Nope.’ I flip the paper over to the front page to find the relevant page number on the printed ticker and I’m flicking through when my eye is drawn to a headline in the Metro pages.

The body has its own visceral intelligence. It reacts before the mind has time to catch up. Daffy Duck has run off a cliff and is paddling in the air. His mind can’t compute, which explains the expression of stupid bewilderment on his face, but his body knows exactly what’s about to happen.

It happened to me when two policewomen appeared at my door with news that my mum had been found dead beside an empty two-litre vodka bottle. It happened when I watched the man in the alley grab the woman’s hair. It’s happening now.

Police appeal for witnesses in festival woman’s death

As I read on it’s as if tiny particles of dark matter begin to collect in the air like soot rising from a coal fire. How could we have missed this? How could we not have known?

Police are launching an appeal for witnesses in the death of 27-year-old Marika Lapska, a Lithuanian national, resident in London. Lapska worked as a food delivery bicycle courier. Her body was discovered in the Thames hours after a music festival in Wapping. She was wearing a festival band around her wrist. Police are anxious to speak to anyone who may have known Lapska or seen her on the night of Saturday 13 August.

There’s the usual Crimestoppers number and below it, almost impossible to look at, is a grainy, heart-stopping CCTV still of a round-faced woman with sharp features and bold, enquiring eyes. Is this her, the woman we all saw in the alley? I scan the cheekbones, the eyes, the full, soft lips, check the shape of the hairline, the placement of the ears, but nothing rings any bells – and there is no particular arrangement of human features, after all, which says, I have been raped. Is this the face? So difficult to tell. There’s no clear picture in my mind, hardly surprising since whoever was attacking her was pushing her face against the wall. But what if I did see her face and have somehow blanked it from my memory? Aren’t eye witnesses supposed to be notoriously unreliable? What if the figure in the alley wasn’t her? What if the woman we saw walked away from that obscene event and brushed herself down and is living her life somewhere in the capital?

Stealing another glance at the picture now, focusing on the woman’s clothes, is there anything there I remember? I take my time and do a bit of peering. It’s then it happens. A sudden illumination, like a camera going off in a dark room. A mind flash in canary yellow and sky blue, the colours of the scarf the woman in the picture is wearing.

I remember that scarf. Every detail remains as clear to me as it was on the night itself, illuminated briefly in Dex’s camera phone. A jaunty canary yellow with sky blue pom-poms. I remember the incongruity of it. The holiday colours, those perky pom-poms which seemed somehow innocent. There’s no question that this was the same woman. How desperately I’d like to shut the pages of the paper and pretend not to have seen her. But it’s too late. Marika Lapska has spoken to me. She’s calling out and it would be inhuman to ignore her now.

‘Guys . . .’ The tremble in my voice startles them. Three pairs of eyes shoot up and settle on me. Dex stops whatever he’s in the midst of saying, his mouth still open. Bo frowns. Anna spins on her toes to face me. There’s a moment’s silence during which an army of thoughts marches through my mind. How did she end up in the river? Did her attacker take her there? Did he push her – or did she launch herself into the water? Did she try to swim or give herself up to death? Aside from the man who raped her were we the last people to see her alive? Isn’t it a crime to leave the scene of a crime? That makes us criminals, doesn’t it?

Is this why Dex is in trouble?

‘Let’s see that picture.’ Dex lurches over and sweeps up the paper.

‘I don’t know,’ he says. ‘I got a good look at her face when I switched on my phone light. That definitely wasn’t her.’

‘I promise you, the woman in the alley was wearing that scarf, I mean, the exact same one.’

Dex takes another look. ‘It’s a scarf, Cass. There’s probably a zillion of them in, like, Accessorize.’

‘Don’t you think we should go to the police, anyway, just in case?’

‘I didn’t see a damn thing,’ Bo says. Dex, who still has the paper, drops it on the table and takes a seat.

‘Mate, were you even there?’ asks Dex.

‘Of course he was,’ Anna says, pulling out a chair and sitting beside Dex. ‘He was standing right behind you.’

‘Oh,’ Dex says, sounding mildly surprised.

‘I might as well not have been, though, because I didn’t see shit,’ Bo says from his perch on the sofa.

‘Dex, Anna and I did see, though, and we really should tell the cops,’ I say.

‘But, darling, what did we see exactly? Because what I saw could easily just have been a pissed knee-trembler. And she was definitely alive last time I saw.’ Anna’s face is a smooth white mask.

‘I really don’t think this was the same woman, Cassie,’ repeats Dex.

Could I really be the only one who saw Marika Lapska raped in that alley on the night of 13 August? What if no one is lying? What if I didn’t see what I think I saw? What if my eyes are deceiving me? But no. I remember so clearly the scarf illuminated in the light of Dex’s phone. The colour of the pattern, as yellow as the moon that night. The bright, sunny blueness of the pom-poms. And what if Dex is right and there are a zillion of those scarves, what are the chances that the woman in the alley and the drowned woman are one and the same? Very high, I’d say. A virtual certainty.

‘I know I saw this woman being attacked. It could have been the same guy who killed her. People, she died.’

‘Casspot, do we even need to do this now? It’s my birthday weekend,’ says Bo.

‘Why don’t you just call the cops yourself if you’re that convinced?’ Dex says. ‘No one’s stopping you.’

‘Cassie, I forbid you to do that. We’d inevitably get dragged in,’ Anna says, giving Dex an urgent, accusatory look.

‘God, no. I’ve got enough on my plate,’ says Bo. Anna is staring intently at Dex.

‘Really?’

‘Yes, really.’

‘Casspot, you’re being tiresome,’ Bo adds more harshly than he probably intends. ‘And I can tell you now, I have absolutely no intention of going to the police. Because I didn’t see shit. As I keep saying.’

‘And I didn’t see anything that could be remotely helpful either,’ says Anna, settling herself into the sofa. ‘We were all rather pissed. Including you, Cassie.’

Dex has moved over to the French windows leading out to the garden now and he’s holding up the wine glasses. ‘Come into the garden with me, Cass, while Anna works her miracles with the veg.’

It’s cold outside. A blanket of midnight blue from which the odd star shines.

‘Isn’t this amazing? We should make the most of it.’ He stands and surveys the scene with the lights of Fortuneswell below us and beyond them, Chesil Beach and the wide midnight blue selvedge of the sea. ‘There was a doc on the TV the other day about kids with alcoholic parents. It was just on, you know? It was talking about, you know, how the kids often . . . about how they develop these saviour complexes because they couldn’t save their parents. The doc said they often grow up unsure about what’s real.’

‘Fuck’s sake, Dex. I know it was her . . . and it’s sort of low to bring my mum into it, don’t you think?’

‘You really don’t know it was her. I had the best view and I hardly saw anything.’

‘You saw a woman being raped. We all did.’ Dex removes a rollie from his pocket, lights it and takes a deep inhale. The thick scent of grass drifts over and out towards the sea.

‘You know it’s an offence to leave the scene of a crime, right?’

‘I could just go to the police on my own?’

‘C’mon, Cass, you know as well as I do that Anna’s right. They’d want to know who you were with. Or there’d be CCTV or something. One way or another we’d get dragged into it. That woman’s just some rando. We live in a city of eight million randos. We can’t fix everyone.’

‘She probably came to London looking for a better life. Don’t we owe her at least a bit of concern?’

‘Look, either she made a really bad choice or she just got really unlucky. It could have happened to anyone.’

‘I could call Crimestoppers and leave an anonymous tip-off.’

This is where you tell me that you’re already dragged into it, Dex. Into something, anyway. This is where you come clean.

Dex sucks on his rollie. ‘Cass, I love you but you’re missing the point. I’m begging you, stay under the radar. Think about that promotion you’re after. What if they decide to prosecute you for leaving the scene of a crime? You think you’re going to get promoted if you end up with a criminal record? You’re not going to be able to work in a school at all. That’s it. End of career. Finito.’

He smiles and, reaching out, grasps my chin between the index finger of his right hand and the thumb, a gesture from the old days, whenever I got tearful or scared.

‘There’s nothing to be gained here, except some misplaced conscience salving. You want to do something virtuous give fifty quid to your favourite charity. You won’t get arrested and you’ll probably be doing more good.’

‘I’m not trying to be a do-gooder. I’m trying to do the right thing.’

‘Well, don’t.’

It’s cold now though the rain has stopped at least. A moth flaps around Dex’s head and, as he bats it away, flutters against the light.

‘Why did the police come and see you?’

He turns, the light now illuminating his left cheek, leaving half his face in the shadows. ‘Did Gav tell you that?’

‘He seemed to think you were in a lot of trouble.’

Dex shakes his head. ‘Gav’s all over the place at the moment. He’s got the wrong end of the stick. You remember that scrap I got into with the numpty at the festival about whether or not I was looking at his girlfriend? The cops were just trying to find out what started the rioting, you know, covering all bases. It was nothing.’

He takes my wine glass and puts it down on the concrete and with one arm around my shoulder he presses me to him. ‘I’m sorry, Cass, but think about what me and Gav have got ahead of us. We really, really don’t need this. For the next four days I just want to pretend I’m young and free again. Is that so much to ask? Tell you what, if you’re still upset about that woman at the end of our trip, we’ll revisit it, OK?’

‘OK.’

‘Good.’ He plants an unexpected kiss on my lips.

And so it’s done. The decision made. There will be no more mention of Marika Lapska or the events at the Wapping Festival. For the next four days the official Group version will be that nothing ever happened.

5 (#ulink_fc2486ab-3dd2-531b-9a4c-3d2f3fce9215)

Bo

A little after 3 a.m., Sunday 14 August, Wapping

The arm around his neck pulling him back smells familiar. He twists his head round and meets Dex’s face.

‘Mate, drop it.’

‘What?’ His body is peeling. He feels weird and wired. He spins back to look at the bloke who, just a few seconds ago, was about to slug him. He hears Dex say, ‘Sorry, mate. My friend’s a bit, you know . . . he’s not trying to disrespect you.’

What the fuck? thinks Bo. He bloody does mean disrespect, he means a fistful of it. He watches the bloke’s body language soften. Stupid bastard wants out of the scrap, looking for any excuse. He’s so tight now, though, everything he’s seen tonight, the adrenalin. Bloody great neither of them has a knife or a gun. He could easily have slipped a blade between that guy’s ribs, thought no more about it, the way he is now. How wired his body feels. His legs slacken, cease their forward momentum, the muscles melting into one another. He’s rooted to the spot. He’ll be fucked if he’s going to give way but it looks like he might not have to come forward. It’s all those hours in the gym, Bo’s thinking. Not the job title or the river view apartment or the strings of women. That fucker knows nothing about any of that.

‘Get out of here, mate, just go,’ he says.

The bloke hesitates. Bo knows exactly what the fucker’s thinking. He’s totting up the square meterage of muscle. Bo plus Dex equals . . . what? The stupid, stupid shit. The bloke’s eyes sweep the small gathered crowd. Ha! Ask the audience, phone a friend, thinks Bo. I fucking dare you.

For an instant it could go either way, then Shitface fills his lungs and blinks and it’s all over. Bo watches him turn and walk away with a bit of a swagger, wait till he’s out of the fist zone, then spit onto the paving. Yeah, whatever.

‘What the fuck?’ Dex’s voice is in his ear. He’s let go of Bo now. Funny, Bo thinks, first time I’ve knowingly been hugged by a gay. He doesn’t mind it. Doesn’t care who or what or how people want to fuck. He laughs to himself. Ha, he’s hardly got a leg to stand on in the sex department, given what . . . given everything, but he’s not a fucking hypocrite. Not like Dex was for all those years.

The small crowd has dissipated now. Nothing to see here. Bo and Dex are alone in the little turning. Dex loves all this, Bo thinks, the rookeries, the remains of cobbled mews that neither the Luftwaffe nor the town planners managed to destroy, all those tiny pathways stinking of urine that snake between the thoroughfares of the old East End and the City. He’s always been drawn to old stuff, whereas old stuff doesn’t interest Bo at all. Ancient stuff, like fossils, fine, otherwise new. Why he loves his apartment so much. A brand-new tower standing between what were once crumbling warehouses and are now bits of retro-fakery. Like someone punched through the river bank straight into the twenty-first century.

‘We should go to A&E, get you looked at,’ Dex says.

‘I’m all right.’ The bits and pieces of his torso are beginning to fuse back together. He feels suddenly tired, exhausted in fact. ‘Think I’ll just go home.’

‘Mate, you’re coming with me.’ Dex is at his side now and sounding insistent. He wonders if Dex knows his secret. Thinks not. Dex is the sort to have said something. It’s actually rather wonderful to be looked after, especially by a man. So long as Dex doesn’t try to interlink arms or pat him or anything gay. He feels protected. Loved, even.

As they walk down the street together, Bo is remembering that time when a stranger decked him outside the house. It must have been when they were living in Chelsea. Had he taken the dog out for a walk around the square? Anyway, the stranger – looking back he thinks maybe a wino or a guy with some mental health issue who had maybe climbed the railings – he recalls running into the house and his father being there, so it must have been a weekend, and his father bundling him back out of the front door ranting about no son of his and saying, ‘Get out there and don’t come back till you’ve showed him a fucking lesson,’ and Bo going back into the square and seeing the guy who’d punched him, collapsed on the bench with piss running down his trousers and his father clapping him on the back when he returned to the house, saying, ‘A man who comes running home without seeing to his business is a bloody coward.’

The adrenaline is beginning to wear off and be replaced by a horrible throbbing on his right side. Is that where the punch landed? Must be.

They are walking north now away from the river and towards the Mile End Road. Dex is saying something about losing each other earlier in the churchyard and seeing some random woman getting beaten up, but to be honest, Bo can’t really focus on anything except the pain in his right side and the reoccurrence of the much deeper emotional pain of his childhood. The first he doesn’t really care about. The second he wants done with.

‘Hey,’ he says, ‘you look like all kinds of shit yourself, mate. What’s with the eye?’ Dex has clearly been in some minor war himself and he’s hoping to deflect the discussion back to safer ground.

‘That massive a-hole wanting to know why I was looking at his girlfriend. Remember, at the festival? I told you.’

They’re walking past a bakery now and the waft of scorching dough reaches Bo’s nostrils and makes him think, briefly, of the pizza delivery girl from earlier.

‘Some women are just trouble,’ he says.

‘Whoa. Where did that come from?’ There’s a pause, which is what Bo has been dreading. He imagines the cops, going to court, all that shit, but to his surprise, Dex says, ‘I’m going to text the girls and let them know where we’re going, though if they’ve got any sense they will have gone home.’

‘Good man,’ Bo says, holding up his right palm for a high five, forgetting the state of Dex’s hand.

They’ve passed Watney Market and are heading up the side of the Holiday Inn now. It’s quiet here. The mess down in Wapping hasn’t reached this far north.

Dex’s phone pings. ‘Cass is home. She and Anna got separated but she says Anna’s phone was running out of battery and she hasn’t heard from her.’

‘Oh?’ Bo says, not liking the sound of that.

Another ping. ‘Hang on,’ Dex says, manoeuvring the phone into his unbruised left hand. ‘That’s Anna now. Says she’ll meet us at the hospital.’

‘Tell her not to bother if she’s already on her way home.’ On balance, Bo would rather just sort this out with Dex. He doesn’t want it to become a whole performance and he absolutely does not wish to be questioned about what happened in the churchyard. It’s a massive relief that Dex hasn’t yet mentioned it and he hopes he won’t. They’ve all been through enough this evening. They are at the entrance to the Royal London’s A&E department when Dex’s phone next pings.

‘Anna says she’s in Ali’s getting a fry-up.’

‘Really? Anna? A fry-up?’

Bo doesn’t remember Anna having any food issues when they were first dating all those years ago, though he probably wouldn’t have noticed in any case. On the contrary, she was curvy back then. All that borderline anorexia stuff must have started after they split up. He recalls that she managed to conquer it for a while, just before her accident, then it came back with a vengeance. Bo presumed she’d got to grips with it again when that thing happened between them – she wasn’t looking particularly skinny that night – and during her pregnancy with Ralphie, but in the last year or so even Bo had noticed that she’d lost weight again. He didn’t really get women. He figured, being gay, Dex probably understood them better. Anything too deep about the female psyche pretty much freaked him out. He just wasn’t all that interested in what was going on in their minds. He was fundamentally an algorithm bloke. Code, formulae, all that stuff. There is an honesty to numbers. They’re clean. An internal laugh bubbles up, despite the pain, which he does his best to suppress and he realises he’s been thinking how ironic that is, for a guy who’d made his money reinventing the dating app. The laugh, though silent, causes the pain in his ribs to surge.

‘She’ll be along in a bit. She says don’t leave A&E without her.’

They’ve just walked through the swing doors into a heave of mostly blokes with what look like minor injuries; casualties of the fighting, Bo supposes. He wonders if there’s a private A&E he can go to, avoid the queues, but if there is, the likelihood of its being here in the East End is pretty low. He thinks about packing it in and just going home, then thinks it might be useful to have himself on camera in the A&E.

They join the line at the triage desk.

‘Fancy a coffee?’ says Dex. In one corner of the waiting room is a bank of vending machines. Bo looks over and spots a camera on the ceiling above the machines. Could be useful. Certainly won’t hurt.

‘You stay in line,’ he says. ‘I’ll go.’

6 (#ulink_5bc9804c-1d68-5e8b-854a-8472de917548)

Cassie

Evening, Thursday 29 September, Isle of Portland

Bo is uncorking an expensive-looking bottle of wine.

‘A Chevalier-Montrachet. Before you say anything, I already know you think I’m a tosser and this weekend I mean to make you all beneficiaries of my tosserdom.’ This is how Group evenings usually start, and end for that matter. With wine and Bo and Bo’s money. Anna, who is popping potatoes in the oven, slaps her hands together, and comes over to receive her glass.

‘Here’s to tossers,’ Dex says. The wine is creamy and complicated and gone in an instant.

‘God, that’s dee-lish,’ Anna says, accepting Bo’s top-up. ‘I can’t tell you how nice it is to be here. You know how much I adore Ralphie . . .’

Making a show of not listening, Bo sticks his fingers in his ears and begins loudly singing, la la la. ‘No babies, diseases or unfortunate events.’

Anna, who has already polished off her second glass, fakes a smile.

‘Let’s eat,’ says Bo.

At the table is Anna’s home-made pâté which is, of course, delicious, because, though Anna herself rarely eats, she makes it her business to be an amazing cook. Even when we were students and all we cooked was beans on toast, Anna would always come up with some delectable little variation on the theme, a grating of cheese, a splash of Lea and Perrins, a sprinkle of mustard powder, a spoonful of treacle and a splash of lemon and then sit and watch us eat it.

‘So, mate, what’s the plan?’ Dex asks, tucking into his third slice of pâté. ‘There’s a farmer’s market at the weekend, apparently.’

‘Fossils. Wine. Walks. A small addition to the Big Black Book. Otherwise, there is no plan,’ Bo says.

Anna spreads a cracker and lays it delicately on her plate. ‘You’re going on a date?’

‘Already arranged,’ Bo says, knocking back his second glass. He’s swiped right on a woman living in one of the villages in the south of the island. ‘Because why not? Let’s just say I’m field testing my app’s performance in rural areas.’

Anna leans in, her eyes bright, and momentarily rests her head on Dex’s shoulder. ‘What about you, darling?’

‘I haven’t really thought about it,’ says Dex.

Bo has helped himself to seconds, and with his mouth full says, ‘Between getting trashed and bouts of casual sex, I’m intending to go on some lovely walks with my friends. Only if you want, though. It’s all really chill. Tomorrow morning we could go over to the Weares. There are feral goats everywhere and the fossiling is good if you get the right day. There’s a climbing outfit down that way too, if anyone fancies it. You climb up this rock face and onto the top by the prison. It’s kind of cool.’

‘Oh God, all that lycra,’ says Dex, camply.

The pâté finished, Anna brings over the chicken. Neither Bo nor I have much talent in the kitchen, Bo because he always eats out and me because there’s always someone else’s washing up in the sink at the flat in Tottenham and because, until a month ago, I was always broke. The supposedly legendary entrepreneurial millennial spirit somehow passed me by. Ambition too. Hence temporary teaching assistant. Great work when there is any but, like any line of work these days that doesn’t involve tech, finance or roasting artisan coffee, terrible pay.

Bo has now opened a third bottle.

‘By the way, Casspot, you’re looking very hot. Is that a new outfit or have you done something to your hair?’

‘Both.’

‘Oh?’ Anna’s eyebrows rise.

Dex leans over from the other side of the table and plants a kiss on my hair. ‘You got that promotion! Why didn’t you say?’ ‘Let’s drink to promotions,’ Bo says, raising his glass.

The glasses clink prettily and for a moment silence falls and is then broken by the strangled screech of some nocturnal creature.

Anna puts down her glass. ‘What the hell was that?’

‘The cry of the Mer-Chicken,’ jokes Bo.

‘We’re about to eat its mate and it’s very, very angry,’ says Dex.

‘Whoever heard of a Mer-Chicken anyway?’ Anna says.

‘Everyone on Portland?’ says Bo.

‘It sounded like a vixen to me,’ I say.

‘Mate, if you’re talking about that thing in the porch it’s a crap stone mermaid with eighties hair someone bought on sale in the local garden centre,’ says Dex. ‘Wooo, I’m scared.’

‘Obviously that’s not the real one,’ Bo says.

‘Oh, and could that be because there is no real one?’ Dex eye-rolls.

‘Portlanders say it’s a harbinger of death,’ Bo goes on.