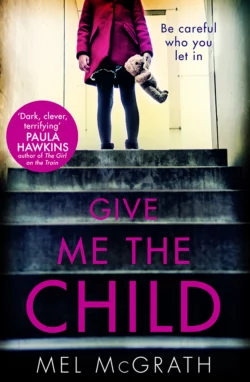

Give Me the Child: the most gripping psychological thriller of the year

Mel McGrath

‘Dark, clever, terrifying’Paula Hawkins, author of The Girl on the Train*The Top Ten Bestseller*‘Gripping and moving’ Erin Kelly‘You won’t want to eat, sleep or blink’ Tammy CohenImagine your doorbell rings in the middle of the night.You open the door to the police.With them is your husband’s eleven-year-old love child. A daughter you never knew he had.Her mother has been found dead in their south London flat.She has nowhere else to go.WOULD YOU TAKE HER IN?Compulsive, dark and devastating, Give Me the Child is a uniquely skilful thriller with an unforgettable twist.

MEL McGRATH is an Essex girl, the author of the critically acclaimed and bestselling family memoir Silvertown. She won the John Llewellyn-Rhys/Mail on Sunday award for Best Writer Under 35 for her first book, Motel Nirvana. She has published three Arctic mysteries featuring the Inuit detective Edie Kiglatuk, under the name MJ McGrath, two of which, White Heat and The Bone Seeker, were longlisted for the CWA Gold Dagger.

She is the co-founder and one of the moving lights of the website Killer Women, which has rapidly established itself as a key forum for crime writing in the UK. This new standalone marks a change in direction.

Copyright (#ulink_ca553c2a-8d2a-5786-a476-cb9faeec2cfd)

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2017

Copyright © Mel McGrath 2017

Mel McGrath asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © July 2017 ISBN: 9780008215613

Version: 2018-07-18

This one’s for my siblings.

Contents

Cover (#u6e6b46b7-4146-560f-9cf5-8629a0b8424b)

About the Author (#uf3fa9365-8c76-5268-af95-d437be2758a0)

Title Page (#u2b36853f-c680-5422-bb8b-50911669d986)

Copyright (#ulink_d10dc095-7249-57e7-96e9-f308d42ed2aa)

Dedication (#uff5d859d-64b7-567b-9f11-c3fa2220c801)

PART ONE: Then

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_3d9920cb-3750-5188-8624-96c327aec1ec)

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_7d6ca58d-b0ec-507b-808a-b0dc696ca8f9)

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_1f8748de-f874-5492-bde0-ee490507bca0)

CHAPTER FOUR (#ulink_9d678cdb-bd60-50b6-86de-4fbe922b7875)

CHAPTER FIVE (#ulink_42e7162f-d884-5a1d-87c0-fe8ba7763550)

CHAPTER SIX (#ulink_853c898c-a4a3-5bd1-b2e4-09e776a98d91)

CHAPTER SEVEN (#ulink_ec69761a-a579-5a59-a1ac-73e932285e13)

CHAPTER EIGHT (#ulink_75c1e5fb-7f69-55a1-a878-6916b8e8a2a7)

CHAPTER NINE (#ulink_7efd4699-f8ec-5e78-a2ca-4074b27aba24)

CHAPTER TEN (#ulink_de83c419-8d26-5e13-bf51-8bb3574ff423)

CHAPTER ELEVEN (#ulink_edf48efe-a202-574c-bd44-541ee0ae79bc)

CHAPTER TWELVE (#ulink_e832a678-f652-54c1-817f-acadb83c64bf)

CHAPTER THIRTEEN (#ulink_a1e2700f-5a3e-5372-ab5a-b928d3bcba42)

CHAPTER FOURTEEN (#ulink_b95f4487-f20b-5c1c-8fbc-e73b00a62529)

CHAPTER FIFTEEN (#ulink_b170a72c-f39d-557e-83df-d91ba93a6467)

CHAPTER SIXTEEN (#ulink_7376f59e-779d-5a84-9eb9-7c8c54baf9e1)

PART TWO: Now

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN (#ulink_866c0467-04c8-5463-809e-dbe5255135ab)

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN (#ulink_5adaad78-9bc2-5c9b-84f3-6bc20e154074)

CHAPTER NINETEEN (#ulink_375b3b18-05d1-538e-a1aa-3efd33545385)

CHAPTER TWENTY (#ulink_55fd3ae7-6f10-5c6b-a6e4-099d1e3690a9)

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE (#ulink_aa7a284f-b5b7-57dd-8042-0b430e87ebc3)

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO (#ulink_961aa4b5-34ba-51eb-b9b8-30c8d5920bf8)

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE (#ulink_22eaee04-f656-58ad-8c73-fa6f3fc3886b)

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR (#ulink_e6d7337f-05b4-54e8-adbe-ed40570491f0)

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE (#ulink_361e4327-ebea-55be-84bf-fbe1326982e6)

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX (#ulink_ccfdc46c-749c-5c80-b8a1-2a4efa53f465)

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN (#ulink_5a2f5ac7-3e0d-59cc-9946-13f135b763a9)

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT (#ulink_d1263dfc-cf88-54a6-b474-33c93a068884)

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE (#ulink_7ef81fda-268f-5d5f-bd54-5c49d7e92a19)

CHAPTER THIRTY (#ulink_206878f4-fc66-5f40-9149-914451c40c3e)

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE (#ulink_ef3f465d-d61b-5a49-9562-d04f5c6e71c8)

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO (#ulink_ebaa579e-3908-58a8-bdff-a924959a7a1b)

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE (#ulink_5832e624-c2a9-5e1b-a2a6-9eeb5ecb8f8a)

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR (#ulink_96571e49-5db8-53b4-98c4-ecad43ac0bc5)

EPILOGUE (#ulink_7b0076b9-17bf-5490-ba23-82e069c28a40)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#ulink_45902d88-fa92-56a6-9d8b-2b2bc4d267cf)

About the Publisher (#ufdff00bf-c192-5eb5-ab49-3614bc72004b)

PART ONE (#ulink_a8a8737b-3e7e-5517-a39b-7f7667066c03)

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_10253a43-a18c-5114-a2bc-12e06f5d0c86)

My first thought when the doorbell woke me was that someone had died. Most likely Michael Walsh. I turned onto my side, pulled at the outer corners of my eyes to rid them of the residue of sleep and blinked myself awake. It was impossible to tell if it was late or early, though the bedroom was as hot and muggy as it had been when Tom and I had gone to bed. Tom was no longer beside me. Now I was alone.

We’d started drinking not long after Freya had gone upstairs. The remains of a bottle of Pinot Grigio for me, a glass or two of red for Tom. (He always said white wine was for women.) Just before nine I called The Mandarin Hut. When the crispy duck arrived I laid out two trays in the living room, opened another bottle and called Tom in from the study. I hadn’t pulled the curtains and through the pink light of the London night sky a cat’s claw of moon appeared. The two of us ate, mostly in silence, in front of the TV. A ballroom dance show came on. Maybe it was just the booze but something about the tight-muscled men and the frou-frou’d women made me feel a little sad. The cosmic dance. The grand romantic gesture. At some point even the tight-muscled men and the frou-frou’d women would find themselves slumped together on a sofa with the remains of a takeaway and wine enough to sink their sorrows, wondering how they’d got there, wouldn’t they?

Not that Tom and I really had anything to complain about except, maybe, a little malaise, a kind of falling away. After all, weren’t we still able to laugh about stuff most of the time or, if we couldn’t laugh, at least have sex and change the mood?

‘Let’s go upstairs and I’ll show you my cha-cha,’ I said, rising and holding out a hand.

Tom chuckled and pretended I was joking, then, wiping his palms along his thighs as if he were ridding them of something unpleasant, he said, ‘It’s just if I don’t crack this bloody coding thing…’

I looked out at the moon for a moment. OK, so I knew how much making a success of Labyrinth meant to Tom, and I’d got used to him shutting himself away in the two or three hours either side of midnight. But this one time, with the men and women still twirling in our minds? Just this one time?

Stupidly, I said, ‘Won’t it wait till tomorrow?’ and in an instant I saw Tom stiffen. He paused for a beat and, slapping his hands on his thighs in a gesture of busyness, he slugged down the last of his wine, rose from the sofa and went to the door. And so we left it there with the question still hanging.

I spent the rest of the evening flipping through the case notes of patients I was due to see that week. When I turned in for the night, the light was still burning in Tom’s study. I murmured ‘goodnight’ and went upstairs to check on Freya. Our daughter was suspended somewhere between dreaming and deep sleep. All children look miraculous when they’re asleep, even the frightening, otherworldly ones I encounter every day. Their bodies soften, their small fists unfurl and dreams play behind their eyelids. But Freya looked miraculous all the time to me. Because she was. A miracle made at the boundary where human desire meets science. I stood and watched her for a while, then, retrieving her beloved Pippi Longstocking book from the floor and straightening her duvet, I crept from the room and went to bed.

Sometime later I felt Tom’s chest pressing against me and his breath on the nape of my neck. He was already aroused and for a minute I wondered what else he’d been doing on screen besides coding, then shrugged off the thought. A drowsy, half-hearted bout of lovemaking followed before we drifted into our respective oblivions. Next thing I knew the doorbell was ringing and I was alone.

Under the bathroom door a beam of light blazed. I threw off the sheet and swung from the bed.

‘Tom?’

No response. My mind was scrambled with sleep and an anxious pulse was rising to the surface. I called out again.

There was a crumpling sound followed by some noisy vomiting but it was identifiably my husband. The knot in my throat loosened. I went over to the bathroom door, knocked and let myself in. Tom was hunched over the toilet and there was a violent smell in the room.

‘Someone’s at the door.’

Tom’s head swung round.

I said, ‘You think it might be about Michael?’

Tom’s father, Michael Walsh, was a coronary waiting to happen, a lifelong bon vivant in the post-sixty-five-year-old death zone, who’d taken the recent demise of his appalling wife pretty badly.

Tom stood up, wiped his hand across his mouth and moved over to the sink. ‘Nah, probably just some pisshead.’ He turned on the tap and sucked at the water in his hand and, in an oddly casual tone, he added, ‘Ignore it.’

As I retreated into the bedroom, the bell rang again. Whoever it was, they weren’t about to go away. I went over to the window and eased open the curtain. The street was still and empty of people, and the first blank glimmer was in the sky. Directly below the house a patrol car was double parked, hazard lights still on but otherwise dark. For a second my mind filled with the terrible possibility that something had happened to Sally. Then I checked myself. More likely someone had reported a burglary or a prowler in the neighbourhood. Worst case it was Michael.

‘It’s the police,’ I said.

Tom appeared and, lifting the sash, craned out of the window.

‘I’ll go, you stay here.’

I watched him throw on his robe over his boxers and noticed his hands were trembling. Was that from having been sick or was he, too, thinking about Michael now? I listened to his footsteps disappearing down the stairs and took my summer cover-up from its hook. A moment later, the front door swung open and there came the low murmur of three voices, Tom’s and those of two women. I froze on the threshold of the landing and held my breath, waiting for Tom to call me down, and when, after a few minutes, he still hadn’t, I felt myself relax a little. My parents were dead. If this was about Sally, Tom would have fetched me by now. It was bound to be Michael. Poor Michael.

I went out onto the landing and tiptoed over to Freya’s room. Tom often said I was overprotective, and maybe I was, but I’d seen enough mayhem and weirdness at work to give me pause. I pushed open the door and peered in. A breeze stirred from the open window. The hamster Freya had brought back from school for the holidays was making the rounds on his wheel but in the aura cast by the Frozen-themed nightlight I could see my tender little girl’s face closed in sleep. Freya had been too young to remember my parents and Michael had always been sweet to her in a way that his wife, who called her ‘my little brown granddaughter’, never was, but it was better this happened now, in the summer holidays, so she’d have time to recover before the pressures of school started up again. We’d tell her in the morning once we’d had time to formulate the right words.

At the top of the landing I paused, leaning over the bannister. A woman in police uniform stood in the glare of the security light. Thirties, with fierce glasses and a military bearing. Beside her was another woman in jeans and a shapeless sweater, her features hidden from me. The policewoman’s face was brisk but unsmiling; the other woman was dishevelled, as though she had been called from her bed. Between them I glimpsed the auburn top of what I presumed was a child’s head – a girl, judging from the amount of hair. I held back, unsure what to do, hoping they’d realise they were at the wrong door and go away. I could see the police officer’s mouth moving without being able to hear what was being said. The conversation went on and after a few moments Tom stood to one side and the two women and the child stepped out of the shadows of the porch and into the light of the hallway.

The girl was about the same age as Freya, taller but small-boned, legs as spindly as a deer’s and with skin so white it gave her the look of some deep sea creature. She was wearing a grey trackie too big for her frame which bagged at the knees from wear and made her seem malnourished and unkempt. From the way she held herself, stiffly and at a distance from the dishevelled woman, it was obvious they didn’t know one another. A few ideas flipped through my mind. Had something happened in the street, a house fire perhaps, or a medical emergency, and a neighbour needed us to look after her for a few hours? Or was she a school friend of Freya’s who had run away and for some reason given our address to the police? Either way, the situation obviously didn’t have anything much to do with us. My heart went out to the kid but I can’t say I wasn’t relieved. Michael was safe, Sally was safe.

I moved down the stairs and into the hallway. The adults remained engrossed in their conversation but the girl looked up and stared. I tried to place the sharp features and the searching, amber eyes from among our neighbours or the children at Freya’s school but nothing came. She showed no sign of recognising me. I could see she was tired – though not so much from too little sleep as from a lifetime of watchfulness. It was an expression familiar to me from the kids I worked with at the clinic. I’d probably had it too, at her age. An angry, cornered look. She was clasping what looked like a white rabbit’s foot in her right hand. The cut end emerged from her fist, bound crudely with electrical wire which was attached to a key. It looked home-made and this lent it – and her – an air that was both outdated and macabre, as if she’d been beamed in from some other time and had found herself stranded here, in south London, in the second decade of the twenty-first century, in the middle of the night, with nothing but a rabbit’s foot and a key to remind her of her origins.

‘What’s up?’ I said, more out of curiosity than alarm. I smiled and waited for an answer.

The two women glanced awkwardly at Tom and from the way he was standing, stiffly with one hand slung on his hip in an attempt at relaxed cool, I understood they were waiting for him to respond and I instinctively knew that everything I’d been thinking was wrong. A dark firework burst inside my chest. The girl in the doorway was neither a neighbour’s kid nor a friend of our daughter.

She was trouble.

I took a step back. ‘Will someone tell me what’s going on?’

When no one spoke I crouched to the girl’s level and, summoning as much friendliness as I could, said, ‘What’s your name? Why are you here?’

The girl’s eyes flickered to Tom, then, giving a tiny, contemptuous shake of the head, as if by her presence all my questions had already been answered and I was being obstructive or just plain dumb, she said, ‘I’m Ruby Winter.’

I felt Tom’s hands on my shoulder. They were no longer trembling so much as hot and spasmic.

‘Cat, please go and make some tea. I’ll come in a second.’

There was turmoil in his eyes. ‘Please,’ he repeated. And so, not knowing what else to do, I turned on my heels and made for the kitchen.

While the kettle wheezed into life, I sat at the table in a kind of stupor; too shocked to gather my thoughts, I stared at the clock as the red second hand stuttered towards the upright. Tock, tock, tock. There were voices in the hallway, then I heard the living room door shut. Time trudged on. I began to feel agitated. What was taking all this time? Why hadn’t Tom come? Part of me felt I had left the room already but here I was still. Eventually, footsteps echoed in the hallway. The door moved and Tom appeared. I stood up and went over to the counter where, what now seemed like an age ago, I had laid out a tray with the teapot and some mugs.

‘Sit down, darling, we need to talk.’ Darling. When was the last time he’d called me that?

I heard myself saying, idiotically, ‘But I made tea!’

‘It’ll wait.’ He pulled up a chair directly opposite me.

When he spoke, his voice came to me like the distant crackle of a broken radio in another room. ‘I’m so sorry, Cat, but however I say this it’s going to come as a terrible shock, so I’m just going to say what needs to be said, then we can talk. There’s no way round this. The girl, Ruby Winter, she’s my daughter.’

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_751f7228-a7ff-5221-ba39-1fc5997b493a)

‘We already have a daughter.’

Tom glanced at me then looked away. It was as though I was viewing him through an early morning fog. He seemed at once both real and spectral. Cold suddenly, I pulled my cover-up more tightly around my body. Words fizzed and flared without my being able to catch hold of them. Stupid thoughts flooded in: This can’t be happening because it’s a Monday and Monday is clinic day.

‘No,’ I said. ‘No, don’t do this to us.’

Tom reached out for my hand and I let him take it. His face was a strange mottled colour, barely recognisable.

‘I’m so, so sorry, Caitlin. I don’t know what to say. I swear I didn’t know anything about her until a few minutes ago. This is as much of a shock to me as it is to you.’

Something rose up in me like a thundercloud, raw and fearsome. I yanked my hand away. This was the worst kind of dream, the one you can’t wake up from, the one that turns out to be real.

‘I doubt that,’ I said.

Tom bit his lip.

I needed the facts, the data. ‘How did this happen? When?’

‘Not long before Freya was born.’

‘When I was in hospital?’ My mind zoomed back to the madness of my pregnancy, how helpless I had been, out of my mind and afraid. ‘Jesus, don’t tell me you had sex with someone in the psych ward?’

Tom shot me a wounded look. ‘Of course not. Please, Cat, just don’t say anything and I’ll try to explain and then you can ask me whatever you want.’

It was quite some explanation. Strung out after one of his visits to the hospital to see me, my husband had gone to a nearby pub with the intention of having a quick drink before getting on the bus home. One turned into two, turned into plenty. A woman appeared, apparently from nowhere – ha ha – and sat next to him at the bar. They’d got chatting and what followed – the whole tired suburban cliché – happened in some shabby B&B around the back of Denmark Hill station. He left for home sometime after dawn and that was that. He’d never seen or heard from the woman again. A moment of madness, the result of overwhelming stress. It hadn’t meant anything then and he begged me to believe how much he regretted it now. I couldn’t know how much, he said. More than anything.

As Tom spoke I couldn’t help thinking just how bloody old and worn and unoriginal the story sounded, a clapped-out tale of a faithless husband led on by some mysterious femme fatale. If you saw it on TV, you’d reach for the remote. This wasn’t us. This wasn’t who we were meant to be. So how was it that it was what we had become? I felt myself reaching for words that had already fled. Odd swoops of energy were tearing up my legs and escaping out into the room through my arms. I made to stand up, got halfway, and then sat down again, defeated by legs that no longer held any weight.

‘What’s her name?’

‘Ruby.’

‘I know that! I mean the woman. Your fuck buddy.’ I twisted my head and glared at him but he averted his gaze.

For a moment there was silence, then Tom said, ‘Her name is Lilly, Lilly Winter.’

I felt as if someone had opened my skull and unloaded a skip of building waste inside. Images of lilies crossed my mind. When had they become junk flowers, the carnations or chrysanthemums of their time, the sweet, cloying gesture you made when you’d run out of more meaningful ones? One thought morphed into another and I remembered what happened with the lilies that time just after Freya was born when we’d thought everything was back to normal and then discovered it wasn’t. Oh God, don’t let this bring the madness back. Please, God, not that. Then my thoughts were broken by the faint murmur of female voices in the living room and I was reminded of the policewoman and the time and the fact that there was still so much to know.

The girl’s name was jammed inside my throat but I couldn’t say it. ‘Why is she here? What’s the policewoman doing?’

Tom folded his arms. ‘There was an accident. Ruby found her mother dead in bed sometime around midnight when she got up to have a pee. The police… I don’t know, Lilly must have told Ruby my name and the police looked me up on some database. In any case, they got my address somehow.’

He went on: ‘They think it was carbon monoxide poisoning – faulty boiler, no batteries in the carbon monoxide detector. The policewoman said you don’t smell it, you don’t hear it, you don’t taste it. If the gas leak is big enough, it only takes thirty seconds to kill you. Ruby’s mother was dead drunk, she wouldn’t have known anything about it.’ He stopped and rubbed a hand across his face as though trying to obliterate something, but I was relieved to see there were no tears. Whatever feelings were going through his heart right now, grief for Lilly Winter wasn’t among them.

‘Oh God, that’s horrible,’ I said.

‘Ruby’s room is in a separate corridor in the flat and she was sleeping with her window wide open, otherwise…’ He frowned and sat with the thought a moment, then, getting up, went over to the kettle and refilled the pot. He brought the tea over then seated himself once more in the chair beside me.

‘Drink this, you’ll feel better.’

I pushed the mug away. I didn’t want to feel better. Not now. Not at five thirty in the morning with my husband’s love child in the room next door. I thought about Freya asleep upstairs, still oblivious to the existence of a half-sister, and wondered what we were about to do to her world.

Tom’s head was in his hands now and he was rubbing at his temples with his thumbs.

‘What were you thinking?’

He swung up so his face was angled towards me and let the air blow out of his lips. ‘Evidently, I wasn’t,’ he said.

I let out a bitter laugh. Even when he wasn’t trying to be funny Tom managed to be amusing. Maybe that’s why we’d lasted as long as we had. The Tom I first met was a glossy, charming man who smelled brightly of the future. I wanted him and he wanted me. We were young and wanting one another seemed if not enough (we weren’t that stupid), then at least the largest part of the deal. Not long after we’d married, life came along. The sex, at first wild, calmed into something more manageable. But it was all OK. We got on well, rarely fought and seemed to want the same things. The years slid by. We had our daughter and moved into a house and enjoyed trips to the seaside on the weekends. We were good parents. We respected one another’s careers. When Tom left Adrenalyze to start his own company, I’d kept the joint account ticking over. He’d supported me as I’d worked long hours at the institute, cheering me from the sidelines when I’d been called as an expert witness in child psychosis. When I’d failed so publically, so devastatingly, and all I’d worked for had come tumbling down, he’d stood by me. Over the years we somehow turned into the couple other couples pretend not to envy. Unflashy, boring, steady. The couple who never got the point of counselling sessions, ‘check-ins’ or ‘date nights’. ‘Never let light in on magic,’ Tom used to say – another of his jokes. We liked it that the outlines of our marriage were blurry and out of focus. Because what is marriage, after all, but a kind of wilful blindness, an agreement to overlook the evidence, a leap of faith for which, in these days of Tinder hook-ups and casual sexting, it pays to be a little myopic?

Tom was going on about something, but I’d stopped listening. The room had begun to feel very claustrophobic. It was as if everything was speeding inwards, converging into a single laser-like beam of almost blinding intensity. Everything has changed. From now on our lives will be different in ways neither of us can predict. Eventually, when I realised he’d fallen silent, I said, simply, ‘I’m so bloody angry I can hardly speak.’

Tom’s chest heaved. ‘I know, I know.’ His voice carried on but the words were lost to me. Instead I began thinking about how things had been after Freya was born, when we’d tried and failed for another child. The doctor’s best guess had been that our bodies were in some undefined way biologically incompatible. Tom hadn’t wanted to go through IVF again or risk another episode of my prenatal psychosis, that wild paranoia which had overwhelmed me in the weeks preceding Freya, and he wouldn’t entertain the idea of adopting. What had followed was a kind of mourning for a child I’d never have, years of hopeless and, for the most part, unspoken longing. Through it all I’d at least been comforted by the notion that neither of us was to blame.

‘Biological incompatibility’ had been my ‘get out of jail free’ card. But now, the arrival of my husband’s other daughter was proof that the ‘incompatibility’ was actually something to do with me. I was the problem. And not just because of my hormones and my predilection for going crazy while pregnant, but because there was something fundamentally wrong with my reproductive system. I was the reason we’d had to resort to IVF. And now here was the proof, in the shape of Ruby Winter. Concrete evidence of the failure of my fertility.

Tom had stopped speaking and was slumped in the chair picking at his fingers. He seemed angry and distracted.

I said, ‘Why isn’t she with a relative or something?’

He looked up and glared. ‘I am a bloody relative,’ then, gathering himself, he said, ‘Sorry. There’s a grandmother, apparently, Lilly Winter’s mother, but they couldn’t get hold of her. In any case, they said Ruby asked to be taken to her dad’s.’ He shot me a pleading look. ‘Look, we’ll sort all of this out and Ruby will go and live with her gran and maybe we’ll see her at the weekends. The most important thing for now is that she’s safe, isn’t it?’

I glanced at the wall clock. It was nearly six in the morning and the little girl in our living room had just lost her mother. I pushed back my hair and forced myself to think straight. In a couple of hours’ time I would be at the institute doing my best to work with a bunch of kids who needed help. How could I possibly live with myself if I didn’t help the kid on my own doorstep?

I stood up and cleared my throat. ‘We’re not done talking about this, not even close. But for now I’m guessing there’ll be paperwork and we’ll need to show the girl to the spare room so she can get some sleep. You go back to the living room. I need a few minutes alone then I’ll follow on with some fresh tea and a glass of juice for’ – the words fell from my mouth like something bitter and unwanted – ‘your daughter.’

While Tom went through the admin with the social worker, Ruby Winter followed me up the stairs in stunned silence, still clutching the rabbit’s foot key, and my heart went out to her, this motherless, pale reed of a girl.

‘You’re safe here,’ I said.

I switched on the bedside lamp and invited her to sit on the bed beside me. Those off-colour eyes scanned my face momentarily, as if she were trying to decide whether I could be trusted. She sat, reluctantly, keeping her distance and with hands jammed between her knees, her skinny frame making only the shallowest of impressions on the mattress. We were three feet from one another now, brought together first by drink and carelessness and then by the terrible fate of her mother. Yet despite all the shock and horror she must have been feeling and my sympathy for her situation, it was as though she possessed some kind of force field which made being close to her unsettling.

I pointed to the rabbit’s foot keyring in her hand.

‘Shall I keep that safe for you? We might need it later, when one of us goes to fetch your things.’ The social worker had brought a bag of basic clothes and toiletries to tide Ruby over while the police did whatever they needed to do in the flat, but the policewoman had told us that they’d been working for several hours already and, given there were no suspicious circumstances, would probably be done by the morning.

Ruby Winter hesitated then handed me the keyring. The combination of fur and metal was warm from her hand.

‘I’m sorry,’ I said. ‘I’m really terribly sorry about your mother. It’s going to take a while to sort everything out, but we will. For now it’s best if you get some sleep.’

I pulled out a toothbrush and wash cloth and a pair of pyjamas from the bag the social worker had brought. ‘Would you like me to come with you to the bathroom?’

Ruby shook her head.

While she was gone, I unpacked the few remaining bits and bobs then sat back on the bed, scooped up the rabbit’s foot keyring and held it in the palm of my hand. It really was an odd thing, the claws dirty and the skin jagged and ratty at the cut end. It had been Lilly Winter’s, I guessed. Who kept animal-part charms these days except maybe Wicca nuts or sinister middle-aged men living with their mothers? I dropped the keyring into my pocket and tried to separate the new arrival from the circumstances of her creation. It wasn’t Ruby’s fault that she’d been conceived in an act of betrayal. But it wasn’t going to be easy to forget it either.

When she returned, dressed in her PJs, I took her wash things and put them on the chest of drawers and sat in the chair at the end of the bed as she slid under the duvet. ‘Did your father tell you we have a daughter about your age? Her name’s Freya. You’ll meet her in the morning.’

I waited for a response that didn’t come. In the dim light thrown by the bedside lamp, with her tiny body and huge hair, the girl appeared otherworldly but also somehow not quite there, as though what I was looking at was a reflection of a girl rather than the girl herself.

‘Your dad told me you have a grandmother.’

Ruby Winter looked up and gave a little smile, oddly empty of feeling, then looked away.

‘She’s a bitch,’ she said flatly. Her voice was soft but with the sharpened edges of a south London accent.

‘I’m sorry you feel that,’ I said. I sensed she was testing me, hoping to catch me out. Perhaps I should have left then and allowed her to sleep but my curiosity overcame me.

‘Did your mother ever tell you anything about your dad?’

Ruby gazed at her fingers and, in the same expressionless tone, she said, ‘Only that he was a real shit.’

This was the kind of behaviour I dealt with on a daily basis at the clinic, but in the here and now, I felt oddly at a loss. ‘I’m sure she didn’t really say that. And, anyway, he isn’t.’

Ruby looked at me then shrugged as if what she had said was of no consequence. ‘I’m tired now.’

‘Of course you are,’ I said, feeling bad for having pushed her into a conversation she didn’t want to have. I went to the door. ‘Sleep now and we’ll talk later.’

Back downstairs I made another pot of tea and some toast and took a tray out to the others. The policewoman was in the middle of saying that there would have to be a post-mortem on Lilly Winter and a report would be filed with the coroner, but it was unlikely that the coroner would call an inquest. The situation at the flat had been straightforward enough. An old boiler, no batteries in the carbon monoxide detector, Lilly passed out from drink.

‘Presumably Ruby will go and live with her grandmother?’ I voiced this as a question but I hoped it was also a statement.

The social worker briefly caught Tom’s eye.

‘That’s the plan,’ Tom said.

The policewoman’s phone went. She answered it, listened briefly, then, turning to Tom, she said, ‘I’m afraid we’ll need to keep you a little longer to go over a few things – but we’re done at the flat if…’ She smiled at me. ‘Perhaps you’d like to go and fetch Ruby’s personal effects?’ She told me the address and began giving me directions.

‘That’s OK, I know the Pemberton Estate.’

‘Oh!’ the policewoman replied, her voice full of amazement, as if neither of us had any business knowing anywhere like the Pemberton.

‘It’s where I grew up,’ I said.

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_3da3851b-9f91-5f21-96a0-db4d0771354b)

According to the police, Lilly Winter had taken over the lease on flat sixty-seven in the Ash Building, one of the red-brick hutches forming part of the original estate, from her mother, Megan Winter, who had moved into the flat from another council property near Streatham. Ruby was born at the flat while her grandmother was still the registered tenant so grandmother, mother and baby must have been living together at that point. The names didn’t mean anything to me and it seemed unlikely that we’d ever coincided. I’d left the place twenty years ago and hadn’t been back since the death of my mother. I didn’t particularly want to go back now, but I was too curious about Lilly Winter to let the opportunity pass. So I left a message on my assistant Claire’s mobile asking her to move my nine o’clock, then Tom and I had a brief discussion about what to tell Freya if she woke up while I was gone and I got in the car and headed south.

When I was growing up, in the nineties, working-class kids of all ethnic varieties lived on the Pemberton, which we called the Ends. The whole district was more than a bit scrappy and shitty. The main road south towards Croydon split the area in two and it was impossible to leave without running into a busy arterial road, as a result of which we rarely ventured far. The surrounding workers’ cottages were occupied by first-generation immigrant Jamaicans who put up cheery curtains and planted their gardens with sunflowers. A handful of elderly whites and some Asian families lived among them and a few middle-class gentrifiers had taken over flats in the villas behind the cottages, though a lot of those were still squatted. But even as kids we could tell that, in some unspecified way, the area was on the move, which made the Ends feel as if it was about to be cut off by the tide. For years there were rumours that the whole estate was to be completely redeveloped and the residents moved elsewhere. At the time, we felt like anarchists, free to run wild without consequences. With hindsight, the instability left us feeling insecure. Those of us who grew up on the Ends did our best to ignore the sense that we had drawn the short straw. We lived for music, sex and a bit of weed. Destiny’s Child, N.W.A., Public Enemy, R ’n’ B, urban, whatever. Friday and Saturday nights you’d meet your homies around the ghetto blaster, roll some joints and have yourselves a party. There were gangs and the odd gang-related ruckus but you could steer your way around them. We felt free but at the cost of knowing we didn’t matter, that kids like us were only of any consequence within the narrow confines of the Ends themselves.

At the traffic lights I made a right, skirting around the southern side of Grissold Park, then up along the wide, leafy road that ran along its western border, and turned again at the filter into a grid of half-gentrified Victorian terraced houses punctuated by shabby corner stores and fried chicken shops.

I slowed and tried to quell the fluttering in my chest. Memories. My manor. Approaching the rack of brutalist tower blocks fronted by older, lower tenements of red brick and what might once have been, but were no longer, cream tiles, I was a teenager again. Furious, mouthy and secretly determined to escape. The parties and the friendships and the ‘what the fuck’ Saturday night feeling had never been quite enough. There had been an itch in me to leave and I knew it would take everything I had to make it happen. Because the trouble with the Pemberton was that if you didn’t get out fast, you didn’t get out at all.

The late July sun was steadily beating down now and, despite the early hour, the estate was already sticky in the heat, the pavements speckled with clumps of dog shit – dark matter in an expanse of Milky Way. Some kids were mooching their way to school, kicking a football along the tea-coloured grass, their elder brothers and sisters hurrying them along, weapon dogs strung in tightly beside them.

I parked up and got out, conscious of being watched – someone is always watching in the Ends. It wouldn’t do to be taken for a social worker or, worse still, a Fed. Two girls were standing at the foot of an external stairway smoking, one in wedge sandals too small for her feet, the other sporting a set of sprayed acrylics which she was tapping on the handrail. Tough kids, showing off their credentials. I headed over; they’d spread the word among whoever needed to know.

‘Hey,’ I said.

‘All right?’ the girl in the wedge sandals replied.

The girl with the acrylics looked me up and down then squinted and tipped her head. ‘You slippin’ here, man.’

‘Nuh uh. This my manor.’

‘I never seen you. Who your people?’

‘Lilly Winter. Me and her got the same baby daddy.’

The girls exchanged glances. Then the girl with the wedge sandals said, ‘You too late, innit. Feds bagged her up. Some accident, I dunno.’

‘Yeah, I heard.’

‘She not my crew.’ The girl turned to her friend. ‘The young’un, though, the gingernut?’

‘Yeah,’ said the friend. ‘Facety bitch.’

‘What I’m sayin’. Nobody give a shit if she gone the same way as her mother, and that’s the truth, innit.’

Sixty-seven Ash Building was the second to last flat on the top floor of one of the older, red-brick blocks overshadowed by the towers, and distinguished only by its tattered, unloved exterior. You didn’t have to step a foot inside to know the place was a dump. Close up, everything about number sixty-seven exuded neglect. It was the only dwelling on that floor which hadn’t been customised with door gates, a window box or some cheerful paint. Where the number had once been attached to the door two rusted screws jutted from their holes. The letter box had fallen out and the hole in the door was duct-taped over. There was grime on the windows and the blue-painted windowsill was feathery with disrepair.

Ruby’s key was an awkward fit and got stuck in the barrel. The door rattled in the jamb but remained firmly shut. I was thinking about giving it a good kick when I became aware of a woman in her early thirties who was peering around the door of number sixty-nine, dressed in a pink onesie.

‘You want something?’ The door opened wider.

‘The little girl who lives here, Ruby Winter? I’m picking up some of her things but the key…’ The woman’s face softened. She said her name was Gloria. Eastern European accent. Something familiar about her that I couldn’t put my finger on.

She came over and, waving me away, pressed her shoulder to the door. ‘You got to push hard. Council said they sort it out, but they don’t. Lilly always waking me up.’ When the door gave, Gloria righted herself and stepped over the threshold. ‘Terrible what happen. And that kid, Ruby, she got no mother.’ When I hesitated, she beckoned me with her hand, saying, ‘Come on then.’

I followed her in. The place was filthy, the smell of stale tobacco overpowering. Damp marks on the walls did a bad job of disguising the thin sheen of grease underneath, and dust and hair had accumulated into dark brown hummocks where the lino had lifted in the corners. Two doors led off the hallway. The first opened into a cramped, dark space which must have been Lilly’s bedroom. Her body had been removed, but something in me resisted entering, afraid of what I might find. A mildewed shower was visible through the other door.

At the end of the hallway was a decent-sized living room, one side of which had been sectioned off and made into a galley kitchen. On the opposite side a door led off into a passageway, presumably to Ruby’s bedroom. The walls were featureless, unless you counted the yellow tar blossoms clambering up the paintwork. A cheap grey pleather sofa sat on the far side, nearest to Ruby’s room. On the other there was a TV stand, though it looked as if someone had been in and removed the TV, leaving the cables splayed over the floor. As I picked my way across old, stained carpet tiles littered with improvised ashtrays, the butts still in them, I found myself wondering whether Tom would have rescued Ruby from all this squalor and neglect if he’d known about her – and realised I wasn’t sure. Strange how you could spend more than a decade of your life with someone, have a child together, and yet discover in the moment it takes for a policewoman to ring a doorbell that you hardly know them at all.

I turned my attention back to the flat. Gloria was standing at the entrance to the kitchen.

‘Is same boiler as in my flat, combi. So is strange.’

‘Strange?’

‘Lilly is leaving window open a little bit. She put nail in the window frame, so no one can get in while she sleeping. But police tell me window was shut this one time.’

‘Is that what’s strange?’

‘No, I mean, is hot at night. So why is boiler on?’

‘The pilot light blew out, the police said.’

‘Oh.’

The death-boiler sat on one side of a long, narrow window in the kitchen. The cover had been removed, presumably by the police, exposing the interior, and it looked like the mechanism had been disabled. Evidently, the carbon monoxide had snaked its way undetected through the living room and down the hallway into Lilly’s room. The policewoman had said that the door leading into a small passageway which separated Ruby’s bedroom from the rest of the flat had probably saved her life. I thought about what Gloria had said and realised there was an undeniable logic to it. I was no expert in boilers but it seemed unlikely to me that a dead pilot light would have led to a massive leakage of carbon monoxide unless the boiler had been firing and the flue had been blocked. If that was the case, the policewoman hadn’t mentioned it. As Gloria said, it was hot, and everyone in the flat was asleep. No reason for the boiler to be on at all.

‘I see what you mean,’ I said. ‘It is odd, isn’t it?’

Gloria was standing at the window with her back to me, looking out across the view of tower blocks and tiled roofs. As she turned I realised where I’d seen her before.

‘You work at St John’s Primary. My daughter’s there.’ I’d seen Gloria after hours polishing the lino tiles.

I pulled Freya’s picture from my wallet.

Gloria’s eyes lit up. She seemed genuinely delighted. ‘Oh yes, I know. Very sweet girl. She want to be Pippi Long Something.’

‘Pippi Longstocking. Yes, she does!’ I smiled. We stood looking at one another for a moment, while the fine thread of female connection wove its spidery web between us.

‘You have any kids?’ I said.

Gloria pressed her lips into a tight line and my instincts told me to change the subject rather than pursue it.

‘Ruby, the girl who lived here? She’s Freya’s half-sister.’

‘They look completely different,’ Gloria said.

‘I’m guessing Ruby looked more like her mother?’ I said and Gloria nodded. ‘I never met Lilly. The police say it’s a miracle Ruby’s alive. It was that door over there and maybe the direction of the draught which saved her.’

‘Miracle,’ Gloria said.

I returned to the kitchen and went back to inspecting the boiler. Gloria followed.

‘Maybe the man make a mistake.’

I asked her what she meant.

‘Repair man, come to look boiler. I don’t know name or nothing. Maybe since two weeks? Lilly knock on my door to borrow twenty pounds to pay him.’

The breath caught in my throat. No one had mentioned a repairman. The policewoman had said only that the police inspection of the boiler revealed the pilot light had gone out – something which could have happened at any time – that there were no batteries in the carbon monoxide detector and that Lilly was dead drunk. According to police, it was a freak accident.

‘Did you report that to the police?’

Gloria let out a raw, indignant yelp. ‘Do I look like a person who talk to police?’ She looked me up and down and raised a finger to her lips. ‘Shh, immigrant like me or brown person like you is same. I don’t say nothing to no one. Pemberton has ears like elephant.’

‘All the same,’ I said, sounding like a judgemental idiot.

Gloria shot me the disapproving look I deserved and began to head for the door. I fumbled around in my pocket for something to write on, found an old receipt and a pen and scribbled down my mobile number.

‘You’re right. I wouldn’t have said anything either when I lived here. But listen, if you see the boiler man again, would you call me? Just as a favour? Or ask him to call me?’ A pause while I thought this through. ‘Best not say anything about Lilly. Just tell him I’ve got some work for him.’

Gloria hesitated for a moment, weighing this – me – up, and after a cursory inspection, folded the paper into her bra. Then she waved a hand in the air and was gone.

I waited until she’d left before going into Ruby’s room. A mattress with no bedframe lay on the floor, beside it a cheap clothes rack almost empty of clothes. There were no drawers. Ruby’s underwear was piled into an Asda bag in the corner. On a tiny plastic bedside table were some old bottles of nail varnish, a few pens, a nail file, a packet of tissues and a few loose batteries. A couple of damp and musty towels on the floor gave out a fusty, faintly fungal smell. I went about the place picking up the clothes and towels and indiscriminately jamming them into the Chinese laundry bags I’d brought from home, my heart full of contradictory feelings, resenting the girl and her mother for intruding into my life, and at the same time feeling desperately sorry for them.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/mel-mcgrath/give-me-the-child-the-most-gripping-psychological-thriller-of/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Mel McGrath

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 25.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ‘Dark, clever, terrifying’Paula Hawkins, author of The Girl on the Train*The Top Ten Bestseller*‘Gripping and moving’ Erin Kelly‘You won’t want to eat, sleep or blink’ Tammy CohenImagine your doorbell rings in the middle of the night.You open the door to the police.With them is your husband’s eleven-year-old love child. A daughter you never knew he had.Her mother has been found dead in their south London flat.She has nowhere else to go.WOULD YOU TAKE HER IN?Compulsive, dark and devastating, Give Me the Child is a uniquely skilful thriller with an unforgettable twist.