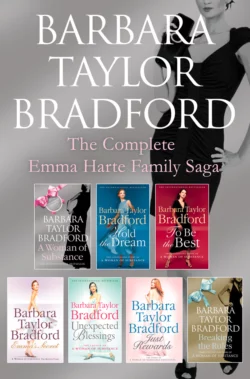

The Emma Harte 7-Book Collection: A Woman of Substance, Hold the Dream, To Be the Best, Emma’s Secret, Unexpected Blessings, Just Rewards, Breaking the Rules

The Emma Harte 7-Book Collection: A Woman of Substance, Hold the Dream, To Be the Best, Emma’s Secret, Unexpected Blessings, Just Rewards, Breaking the Rules

Barbara Taylor Bradford

The unputdownable multi-million copy bestseller charting the rags to riches story of Emma Harte.This exclusive ebundle includes all 7 titles in the epic Harte family saga, featuring the legendary woman of substance Emma Harte and her descendants through the generations:A Woman of Substance; Hold the Dream; To Be the Best; Emma’s Secret; Unexpected Blessings; Just Rewards and Breaking the Rules

THE EMMA HARTE 7-BOOK COLLECTION

A Woman of Substance Hold the Dream To Be the Best Emma’s Secret Unexpected Blessings Just Rewards Breaking the Rules

BY BARBARA TAYLOR BRADFORD

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_75b79413-7504-5b6c-950e-f315b508dff7)

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

A Woman of Substance First published in Great Britain by Grafton Books 1981

Hold the Dream First published in Great Britain by Granada Publishing 1985

To Be the Best First published in Great Britain by Granada Publishing 1988

Emma’s Secret First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2003

Unexpected Blessings First published in Great Britain by by HarperCollinsPublishers 2005

Just Rewards First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2005

Breaking the Rules First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2009

Copyright © Barbara Taylor Bradford 1981, 1985, 1988, 2003, 2005, 2009

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2014 Cover images © Shutterstock.com

A Woman of Substance: Cover image © Richard Wright/Corbis

Hold the Dream: Cover photography © Jean-François Talivez

To Be the Best: Cover photography © Jean-François Talivez

Emma’s Secret: Cover photography © Jean-François Talivez

Unexpected Blessings: Cover photography © Jean-François Talivez

Just Rewards: Cover photography © Jean-François Talivez

Breaking the Rules: Jacket image © Vincent Besnault/Getty images

Barbara Taylor Bradford asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBNs:

A Woman of Substance: 9780007321421 Hold the Dream: 9780586058497 To Be the Best: 9780586070345 Emma’s Secret: 9780006514411 Unexpected Blessings: 9780006514428 Just Rewards: 9780007197583 Breaking the Rules: 9780007304073

Ebook Edition © DECEMBER 2014 ISBN: 9780008115333

Version: 2017-10-27

CONTENTS

COVER (#ueec83c20-5bca-56de-b523-df939bd9d610)

TITLE PAGE (#u85a541c7-5729-52bf-b603-aed7f5e6824c)

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_13d204d0-1a0b-5b9e-9ee7-c182a4663f4b)

A WOMAN OF SUBSTANCE (#uc349ac54-73bb-531f-bfca-5a949c19efa3)

HOLD THE DREAM (#uf61051dc-c152-5929-ab6b-9b57b9c0c7e5)

TO BE THE BEST (#u31dff0a6-bff8-505f-ab8e-121c44991c86)

EMMA'S SECRET (#u75275d03-4224-5075-be64-1c8e67afbb78)

UNEXPECTED BLESSINGS (#u8047681c-07d8-503d-87b1-8a0744fe4628)

JUST REWARDS (#ud183cc2c-d620-51a7-a0fd-69be14bacdf1)

BREAKING THE RULES (#ud183cc2c-d620-51a7-a0fd-69be14bacdf1)

KEEP READING (#u0e003334-0ae5-5a6e-9383-9df081d8d0b3)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (#ulink_dfd8cd77-e643-5355-a73d-52e7e2656f4e)

ALSO BY BARBARA TAYLOR BRADFORD (#ulink_73ce3dff-882d-55a9-ad2d-ad22fa8e7bbd)

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER (#ulink_88180f04-37af-5578-a4a5-3af299a15269)

BARBARA TAYLOR BRADFORD

A Woman of Substance

DEDICATION (#ulink_35e2013e-98c6-526c-85ff-4fff6460d88e)

For Bob and my parents – who know the reason why

EPIGRAPH (#ulink_4146f676-d0d5-5128-ae68-7255e16dbf1c)

The value of life lies not in the length of days, but in the use we make of them; a man may live long, yet get little from life.

Whether you find satisfaction in life depends not on your tale of years, but on your will.

– MONTAIGNE, Essays

I have the heart of a man, not of a woman, and I am not afraid of anything …

– ELIZABETH I, Queen of England

CONTENTS

COVER (#uc349ac54-73bb-531f-bfca-5a949c19efa3)

TITLE PAGE (#u6d702c01-7c58-59ef-a828-13e427f8ce96)

DEDICATION (#ulink_d1491aa9-c30e-5c47-993c-6ae947137d66)

EPIGRAPH (#ulink_83a50ded-3c91-580c-a761-7fee1c8e8919)

FOREWORD (#ulink_e4ef0123-ebb1-508d-80e9-549ef801ff26)

PART ONE: The Valley 1968 (#ulink_cd3fa583-109d-5fb7-9f8a-11223a8e75d3)

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_97e474ac-5fe2-5c0e-90c1-9d97cafffc48)

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_a498c797-428b-5b4a-a24f-d49e4396cfeb)

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_2fd5713a-09a6-55b9-b50f-999efe8492ed)

CHAPTER FOUR (#ulink_b193dc20-f28b-54e4-8114-de486710a302)

PART TWO: The Abyss 1904–5 (#ulink_b522cca2-1fcf-52bc-9668-cdb26392ac90)

CHAPTER FIVE (#ulink_9289918c-ba0d-5633-836c-dd5b7ee70b80)

CHAPTER SIX (#ulink_bd05c46f-81ed-5fcd-9fd0-c854d0aab6ca)

CHAPTER SEVEN (#ulink_647c5b11-6f63-50f6-bf69-278fd5986c03)

CHAPTER EIGHT (#ulink_ecac37de-c649-5e83-b884-2054fbc2f688)

CHAPTER NINE (#ulink_cc37c914-4a35-5586-8052-39a2d82b8cd0)

CHAPTER TEN (#ulink_7694385d-5705-56a3-b9a5-0c95cd1c7420)

CHAPTER ELEVEN (#ulink_9e0705c5-3401-54c6-bb6b-c03ecaebef5b)

CHAPTER TWELVE (#ulink_84ae07ee-aed1-5d3d-8644-d66b0467bbd4)

CHAPTER THIRTEEN (#ulink_82f8a08d-0118-5941-b2e0-9f53c8720d91)

CHAPTER FOURTEEN (#ulink_ea7f3f4f-a5bb-5f79-91d6-c619c8c22faa)

CHAPTER FIFTEEN (#ulink_1f955b8e-77f8-5e1e-95e8-9b7dd8824ca4)

CHAPTER SIXTEEN (#ulink_6cf68b9a-316c-5fa6-a2e2-7a7ae583ba65)

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN (#ulink_f1c450b2-6aa0-5b35-9768-c113654a6bf2)

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN (#ulink_97dc23e5-fcf3-5f1d-9198-3dfd89e5c912)

CHAPTER NINETEEN (#ulink_bea98ad9-8201-5fcb-bf1f-ac14cea6ccda)

CHAPTER TWENTY (#ulink_62f51c20-6b02-5dfc-b214-46ee8b051ced)

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE (#ulink_38411f9f-061e-5bc1-8681-08d9fc17905e)

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO (#ulink_4a7403c6-662f-58f9-bbfb-1cdbe7ab08b8)

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE (#ulink_a222e1f6-cce2-596e-8a4b-289238f14e82)

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR (#ulink_edf3a6d4-9104-5066-ac3e-06614616ac55)

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE (#ulink_5637721a-264f-5265-80b4-5cc6d8ccff49)

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX (#ulink_668e0aa8-6f9b-56ab-ac83-4c466620ee47)

PART THREE: The Slope 1905–10 (#ulink_a0cda7f9-1047-5009-a6b5-7a3e9147b32e)

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN (#ulink_899c2f09-f7c5-5ef6-9248-472fd6da1e36)

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT (#ulink_014ebfde-a169-5a9b-a67b-81b00d3e7f8d)

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE (#ulink_c9155fc4-a74d-57f5-8717-91dcfe1144da)

CHAPTER THIRTY (#ulink_e417b488-20de-5a56-89d6-b258a673b56e)

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE (#ulink_a6f6d92e-3294-571f-b828-93d425705a41)

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO (#ulink_0f8b61e8-b9d0-52ab-be9f-012fb0d25e0d)

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE (#ulink_b1822fae-02cc-5be0-972b-f94d8f5ae735)

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR (#ulink_3a70a97d-dcc1-5528-8539-736ea8ad326e)

CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE (#ulink_fd9c2cca-ba8e-55a5-a9a4-9627d2493f96)

PART FOUR: The Plateau 1914–17 (#ulink_7963cef3-4206-5bcb-bc29-eab7d65c9c62)

CHAPTER THIRTY-SIX (#ulink_30a604ff-39b8-5f7d-9cdb-a70941924be1)

CHAPTER THIRTY-SEVEN (#ulink_40de3bf7-1668-50f0-8baf-5d27e6415c56)

CHAPTER THIRTY-EIGHT (#ulink_a68f5f6c-6698-52e7-8ec2-ae7e8dddd73c)

CHAPTER THIRTY-NINE (#ulink_9d0fffb6-02cd-59af-a359-dd5d58541e98)

CHAPTER FORTY (#ulink_e1a2c14a-ca59-5746-b9bb-2781b2180d99)

CHAPTER FORTY-ONE (#ulink_32d6a2ae-25bd-5a4b-b2d0-748b272fe6d1)

CHAPTER FORTY-TWO (#ulink_b7adbc49-aa6c-59d4-80de-0243c82dae49)

CHAPTER FORTY-THREE (#ulink_8cea162f-3f67-5d66-9685-77499f42887f)

PART FIVE: The Pinnacle 1918–50 (#ulink_1a4a1f8b-6153-5e71-a889-c60f0dbb493b)

CHAPTER FORTY-FOUR (#ulink_99a2919a-18c4-5d41-9fe9-2c8894015344)

CHAPTER FORTY-FIVE (#ulink_998f9a3a-536a-575f-b7d1-8c83b2ea7166)

CHAPTER FORTY-SIX (#ulink_34de68c7-5680-59b2-bb73-cbe442b7d8c8)

CHAPTER FORTY-SEVEN (#ulink_1ba93645-266f-583a-b0b5-652b32720f62)

CHAPTER FORTY-EIGHT (#ulink_845c84c1-1985-5349-82d2-347065609ea5)

CHAPTER FORTY-NINE (#ulink_a1126079-809b-516f-97d2-a56e9180b6ef)

CHAPTER FIFTY (#ulink_71428108-f510-53b5-9ae3-2a0ec3144376)

CHAPTER FIFTY-ONE (#ulink_21871fca-2863-5143-a17f-4cb82cee928f)

CHAPTER FIFTY-TWO (#ulink_0368c9e0-73cd-5ddd-be24-86db99c0c309)

CHAPTER FIFTY-THREE (#ulink_a4a0bbc2-89bd-59ba-ac41-97d2c7d5bae9)

CHAPTER FIFTY-FOUR (#ulink_e89537df-9870-5a09-906f-9f9a02717681)

CHAPTER FIFTY-FIVE (#ulink_daf45039-6e32-5268-93c6-0f0f03c0d9d3)

CHAPTER FIFTY-SIX (#ulink_0337c501-cad8-57b8-bc77-250a5d69eb74)

CHAPTER FIFTY-SEVEN (#ulink_83db1061-3810-5089-beb7-e7855c918a9c)

CHAPTER FIFTY-EIGHT (#ulink_568c14b4-5c4d-53e1-aa4a-7bc6afaa16fb)

CHAPTER FIFTY-NINE (#ulink_de843fb8-3f18-5c62-8f97-f3ce7c7a9dc3)

PART SIX: The Valley 1968 (#ulink_163f5933-6c47-5876-9afa-45fdc3e072fa)

CHAPTER SIXTY (#ulink_101994f0-8e22-5f76-a367-da30e649340f)

CHAPTER SIXTY-ONE (#ulink_a6c35b1e-b255-517b-bc40-dd23ee6b14cb)

CHAPTER SIXTY-TWO (#ulink_72fa8dc0-7dad-5d7f-a5ac-caa64f358d6f)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#ulink_8f4cd341-4deb-55ca-9218-6d0af5d098d9)

FOREWORD (#ulink_9f8d6576-d804-5f2a-b5ae-f39851259aa9)

When A Woman of Substance was published thirty years ago I was thrilled and also very surprised when the book, my first novel, became such a runaway bestseller. What amazed me even more was that it reached the top of the bestseller charts in so many other countries, and was available in a variety of foreign languages. You see, when I had finished writing the book it occurred to me that perhaps it was a little too parochial, since so much of it was set in my native Yorkshire. My French publisher soon set me straight about that, ‘Nobody cares that much about location,’ he explained. ‘It’s Emma that intrigues and captivates. We all become enmeshed in her story and want to keep reading about her, to see how she ends up.’

Well, she ended up being a role model for women all around the world. I soon discovered that Emma both inspired and empowered women of all ages. She was strong and brave, bold and fearless, and she broke the glass ceiling long before that phrase was even invented. In many ways she redefined a new generation of women, and she still does today … in ninety countries and forty languages. And all I wanted to do was tell a good tale about an enterprising woman who makes it in a man’s world when women weren’t doing that.

I suppose I succeeded more than I realized at the time. Emma and her life story captured everybody’s imagination, and still does. Tough and often ruthless, brilliant when it came to dissimulations, she was an amazing businesswoman, and could be a powerful and fearsome adversary when she thought this was necessary. Yet conversely, she was kind and loving, had an understanding heart, was generous to a fault, especially to her family, and the most loyal of women.

Aside from its publishing success, A Woman of Substance was brilliantly brought to life on our television screens. Deborah Kerr played Emma as the older woman, and Jenny Seagrove was Emma from her early youth to her mid-forties.

I will never forget seeing the film for the first time in our home, long before it had been aired. I started to cry and was filled with emotion when I saw Jenny in the role of Emma, trampling across the implacable Yorkshire moors, where she bumped into a young man called Blackie O’Neill, a character who flew so easily and swiftly from my pen, and was played by Liam Neeson in the film. They were both astounding in these roles, as was Deborah Kerr and Barry Bostwick as Paul McGill, the great love of Emma’s life. I will never forget the marvelous performances given by Sir John Mills, Gayle Hunnicutt, Barry Morse, Nicola Pagett and Miranda Richardson, to name just a few other members of this extraordinary cast. And the most wonderful thing was that each actor looked exactly right, almost as I had imagined them in my mind’s eye.

I was very proud when the six hour mini-series was nominated for an Emmy, and although it didn’t win, it nevertheless had the word winner written all over it. It is still playing somewhere in the world as I write this, and the book is still selling in every country where I am published. Everyone tells me it’s as fresh and beguiling as ever and that Emma Harte is as much a woman of today, in 2009, as she was in 1979.

No author who sits at a desk for hours at a time wants to write a book that nobody reads, and I am proud that my first novel has sold over thirty-one million copies worldwide. It is also on the list of the ten best-selling books of all time, up there with Gone With the Wind, and other famous classics. In fact, A Woman of Substance has become a classic itself, and I smile every time I see the phrase ‘a woman of substance’ used to describe other successful or unique women. My title has seeped into everyday language and is used all the time, in newspapers, magazines and on the airwaves.

I started writing when I was seven years old, encouraged by my mother who was a voracious reader. When I was ten she found one of my stories and sent it to a children’s magazine. Imagine my surprise and joy when they accepted it, and even paid me seven shillings and sixpence for it. But it was the by-line ‘Barbara Taylor’ that impressed me and I announced to my mother that I was going to be a writer when I grew up. Many years later when I gave my mother a copy of the book she looked at me and said quietly, ‘This is the fulfillment of your childhood dream.’ It was.

Of all the things that have happened to my first novel over the years, the one that has truly astonished me has been the desire on the part of my readers to have more books about Emma Harte and her family. To date A Woman of Substance has spawned five other novels, and a sixth, entitled Breaking The Rules, is published alongside this anniversary edition.

My husband Robert Bradford was the first person to hear the title Breaking the Rules, and he loved it immediately. Then he reminded me that this was what Emma had always done throughout her life … she had flaunted the rules and done it her way. And I can only say bravo to that.

Barbara Taylor Bradford

PART ONE (#ulink_5b45d57d-b3a2-521a-8aac-f70b4084017f)

The Valley 1968 (#ulink_5b45d57d-b3a2-521a-8aac-f70b4084017f)

He paweth in the valley and rejoiceth in his strength: he goeth on to meet the armed men.

– JOB

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_3b9867bc-6d07-556d-af3c-d8e451e8d23b)

Emma Harte leaned forward and looked out of the window. The private Lear jet, property of the Sitex Oil Corporation of America, had been climbing steadily up through a vaporous haze of cumulus clouds and was now streaking through a sky so penetratingly blue its shimmering clarity hurt the eyes. Momentarily dazzled by this early-morning brightness, Emma turned away from the window, rested her head against the seat, and closed her eyes. For a brief instant the vivid blueness was trapped beneath her lids and, in that instant, such a strong and unexpected feeling of nostalgia was evoked within her that she caught her breath in surprise. It’s the sky from the Turner painting above the upstairs parlour fireplace at Pennistone Royal, she thought, a Yorkshire sky on a spring day when the wind has driven the fog from the moors.

A faint smile played around her mouth, curving the line of the lips with unfamiliar softness, as she thought with some pleasure of Pennistone Royal. That great house that grew up out of the stark and harsh landscape of the moors and which always appeared to her to be a force of nature engineered by some Almighty architect rather than a mere edifice erected by mortal man. The one place on this violent planet where she had found peace, limitless peace that soothed and refreshed her. Her home. She had been away far too long this time, almost six weeks, which was a prolonged absence indeed for her. But within the coming week she would be returning to London, and by the end of the month she would travel north to Pennistone. To peace, tranquillity, her gardens, and her grand-children.

This thought cheered her immeasurably and she relaxed in her seat, the tension that had built up over the last few days diminishing until it had evaporated. She was bone tired from the raging battles that had punctuated these last few days of board meetings at the Sitex corporate headquarters in Odessa; she was supremely relieved to be leaving Texas and returning to the relative calmness of her own corporate offices in New York. It was not that she did not like Texas; in point of fact, she had always had a penchant for that great state, seeing in its rough sprawling power something akin to her native Yorkshire. But this last trip had exhausted her. I’m getting too old for gallivanting around on planes, she thought ruefully, and then dismissed that thought as unworthy. It was dishonest and she was never dishonest with herself. It saved so much time in the long run. And, in all truthfulness, she did not feel old. Only a trifle tired on occasion and especially when she became exasperated with fools; and Harry Marriott, president of Sitex, was a fool and inherently dangerous, like all fools.

Emma opened her eyes and sat up impatiently, her mind turning again to business, for she was tireless, sleepless, obsessive when it came to her vast business enterprises, which rarely left her thoughts. She straightened her back and crossed her legs, adopting her usual posture, a posture that was contained and regal. There was an imperiousness in the way she held her head and in her general demeanour, and her green eyes were full of enormous power. She lifted one of her small, strong hands and automatically smoothed her silver hair, which did not need it, since it was as impeccable as always. As indeed she was herself, in her simple yet elegant dark grey worsted dress, its severeness softened by the milky whiteness of the matchless pearls around her neck and the fine emerald pin on her shoulder.

She glanced at her granddaughter sitting opposite, diligently making notes for the coming week’s business in New York. She looks drawn this morning, Emma thought, I push her too hard. She felt an unaccustomed twinge of guilt but impatiently shrugged it off. She’s young, she can take it, and it’s the best training she could ever have, Emma reassured herself and said, ‘Would you ask that nice young steward – John, isn’t it? – to make some coffee please, Paula. I’m badly in need of it this morning.’

The girl looked up. Although she was not beautiful in the accepted sense of that word, she was so vital she gave the impression of beauty. Her vividness of colouring contributed to this effect. Her glossy hair was an ink-black coif around her head, coming to a striking widow’s peak above a face so clear and luminous it might have been carved from pale polished marble. The rather elongated face, with its prominent cheek-bones and wide brow, was alert and expressive and there was a hint of Emma’s resoluteness in her chin, but her eyes were her most spectacular feature, large and intelligent and of a cornflower blue so deep they were almost violet.

She smiled at her grandmother and said, ‘Of course, Grandy. I’d like some myself.’ She left her seat, her tall slender body moving with grace. She’s so thin, Emma commented to herself, too thin for my liking. But she always has been. I suppose it’s the way she’s made. A leggy colt as a child, a racehorse now. A mixture of love and pride illuminated Emma’s stern face and her eyes were full of sudden warmth as she gazed after the girl, who was her favourite, the daughter of Emma’s favourite daughter, Daisy.

Many of Emma’s dreams and hopes were centred in Paula. Even when she had been only a little girl she had gravitated to her grandmother and had also been curiously attracted to the family business. Her biggest thrill had been to go with Emma to the office and sit with her as she worked. While she was still in her teens she had shown such an uncanny understanding of complex machinations that Emma had been truly amazed, for none of her own children had ever displayed quite the same aptitude for her business affairs. Emma had secretly been delighted, but she had watched and waited with a degree of trepidation, fearful that the youthful enthusiasm would be dissipated. But it had not waned, rather it had grown. At sixteen Paula scorned the suggestion of a finishing school in Switzerland and had gone immediately to work for her grandmother. Over the years Emma drove Paula relentlessly, more harsh and exacting with her than with any of her other employees, as she assiduously educated her in all aspects of Harte Enterprises. Paula was now twenty-three years old and she was so clever, so capable, and so much more mature than most girls of her age that Emma had recently moved her into a position of significance in the Harte organization. She had made Paula her personal assistant, much to the stupefaction and irritation of Emma’s oldest son, Kit, who worked for the Harte organization. As Emma’s right hand, Paula was privy to most of her corporate and private business and, when Emma deemed fit, she was her confidante in matters pertaining to the family, a situation Kit found intolerable.

The girl returned from the galley kitchen laughing. As she slid into her seat she said, ‘He was already making tea for you, Grandy. I suppose, like everyone else, he thinks that’s all the English drink. But I said we preferred coffee. You do, don’t you?’

Emma nodded absently, preoccupied with her affairs. ‘I certainly do, darling.’ She turned to her briefcase on the seat next to her and took out her glasses and a sheaf of folders. She handed one to Paula and said, ‘Please look at these figures for the New York store. I would be interested in what you think. I believe we are about to take a major step forward. Into the black.’

Paula looked at her alertly. ‘That’s sooner than you thought, isn’t it? But then your reorganization has been very drastic. It should be paying off by now.’ Paula opened the folder with interest, her concentration focused on the figures. She had Emma’s talent for reading a balance sheet with rapidity and detecting, almost at a glance, its strengths and its weaknesses and, like her grandmother’s, her business acumen was formidable.

Emma slipped on her horn-rimmed glasses and took up the large blue folder that pertained to Sitex Oil. As she quickly ran through the papers there was a gleam of satisfaction in her eyes. She had won. At last, after three years of the most despicable and manipulative fighting she had ever witnessed, Harry Marriott had been removed as president of Sitex and kicked upstairs to become chairman of the board.

Emma had recognized Marriott’s shortcomings years ago. She knew that if he was not entirely venal he was undoubtedly exigent and specious, and dissimulation had become second nature to him. Over the years, success and the accumulation of great wealth had only served to reinforce these traits, so that now it was impossible to deal with him on any level of reason. As far as Emma was concerned, his judgement was crippled, he had lost the little foresight he had once had, and he certainly had no comprehension of the rapidly shifting inner worlds of international business.

As she made notations on the documents for future reference, she hoped there would be no more vicious confrontations at Sitex. Yesterday she had been mesmerized by the foolhardiness of Harry’s actions, had watched in horrified fascination as he had so skilfully manoeuvred himself into a corner from which Emma knew there was no conceivable retreat. He had appealed to her friendship of some forty-odd years only once, floundering, helpless, lost; a babbling idiot in the face of his adversaries, of whom she was the most formidable. Emma had answered his pleas with total silence, an inexorable look in her pitiless eyes. And she had won. With the full support of the board. Harry was out. The new man, her man, was in and Sitex Oil was safe. But there was no joy in her victory, for to Emma there was nothing joyful in a man’s downfall.

Satisfied that the papers were in order, Emma put the folder and her glasses in her briefcase, settled back in her seat, and sipped the cup of coffee. After a few seconds she addressed Paula. ‘Now that you have been to several Sitex meetings, do you think you can cope alone soon?’

Paula glanced up from the balance sheets, a look of astonishment crossing her face. ‘You wouldn’t send me in there alone!’ she exclaimed. ‘It would be like sending a lamb to the slaughter. You wouldn’t do that to me yet.’ As she regarded her grandmother she recognized that familiar inscrutable expression for what it truly was, a mask to hide Emma’s ruthless determination. My God, she does mean it, Paula thought with a sinking feeling. ‘You’re not really serious, are you, Grandmother?’

‘Of course I’m serious!’ A flicker of annoyance crossed Emma’s face. She was surprised at the girl’s unexpected but unequivocal nervousness, for Paula was accustomed to high-powered negotiations and had always displayed nerve and shrewdness. ‘Do I ever say anything I don’t mean? You know better than that, Paula,’ she said sternly.

Paula was silent and, in that split second of silence, Emma became conscious of her tenseness, the startled expression that lingered on her face. Is she afraid? Emma wondered. Surely not. She had never displayed fear before. She was not going to turn out like the others, was she? This chilling possibility penetrated Emma’s brilliant mind like a blade and was so unacceptable she refused to contemplate it. She decided then that Paula had simply been disturbed by the meeting, perhaps more so than she had shown. It had not disturbed Emma; rather it had irritated her, since she had found the bloodletting unnecessary and a waste of precious time, and therefore all the more reprehensible. But she had seen it all before, had witnessed the rapacious pursuit of power all of her life, and she could take it in her stride. With her strength she was equipped to deal with it dispassionately. As Paula will have to learn to do, she told herself.

The severity of her expression did not change, but her voice softened as she said, ‘However, I won’t send you alone to Sitex until you know, as I already know, that you can handle it successfully.’

Paula was still holding the folder in her hands, delicate hands with tapering fingers. She put the folder down and sat back in her seat. She was regaining her composure and, gazing steadily at her grandmother, she said quietly, ‘What makes you think they would listen to me the way they listen to you? I know what the board think of me. They regard me as the spoiled, pampered granddaughter of a rich and powerful woman. They dismiss me as empty-headed and silly, a brainless pretty face. They wouldn’t treat me with the same deference they treat you, and why should they? I’m not you.’

Emma pursed her lips to hide a small amused smile, sensing injured pride rather than fear. ‘Yes, I know what they think of you,’ she said in a much milder tone, ‘and we both know how wrong they are. And I do realize their attitude riles you, darling. I also know how easy it would be for you to disabuse them of their opinions of you. But I wonder, Paula, would you want to do that?’

She looked at her granddaughter quizzically, a shrewd glint in her eyes, and when the girl did not answer, she continued: ‘Being underestimated by men is one of the biggest crosses I’ve had to bear all of my life, and it was particularly irritating to me when I was your age. However, it was also an advantage and one I learned to make great use of, I can assure you of that. You know, Paula, when men believe they are dealing with a foolish or stupid woman they lower their guard, become negligent and sometimes even downright reckless. Unwittingly they often hand you the advantage on a plate.’

‘Yes, but …’

‘No buts, Paula, please. And don’t you underestimate me. Do you honestly think I would expose you to a dangerous situation?’ She shook her head and smiled. ‘I know what your capabilities are, my dear. I have always been sure of you. More sure of you than any of my own children, apart from your mother, of course, and you’ve never let me down.’

‘I appreciate your confidence, Grandmother,’ Paula replied steadily, ‘but I do find it hard to deal effectively with people who don’t take me seriously and the Sitex board do not.’ A stubborn look dulled the light in her eyes and her mouth became a thin tight line, an unconscious replica of her grandmother’s.

‘You know, you really surprise me. You have enormous self-assurance and have dealt with all manner of people, on all levels, since you were quite a young girl. It has never seemed to disturb you before.’ Emma sighed heavily. ‘And haven’t I told you countless times that what people think about you in business is unimportant. The important thing is for you to know who you are and what you are. And frankly I always thought you did.’

‘I do!’ Paula cried, ‘but I am not sure that I have your capacity for hard work, or your experience.’

Emma’s face darkened. ‘Yes, you do. Furthermore, you have all the advantages of education I never had, so don’t let me hear you speak so negatively of yourself again! I’ll concede experience to you, but only to a degree. And you are gaining more of that every day. I’ll tell you in all honesty, Paula, I would have no compunction in sending you back to Sitex tomorrow – and without me. Because I know you would handle yourself brilliantly. After all, I raised you, I trained you. Don’t you think I know what I created?’

A carbon copy of yourself and a copy is never quite as good as the original, Paula thought dryly, but said, ‘Please don’t be angry, Grandmother.’ Her voice was gentle. ‘You did a wonderful job. But I am not you. And the board are very aware of that. It’s bound to affect their attitude!’

‘Now listen to me!’ Emma leaned forward and her narrowed eyes were like green glass slits underneath the old wrinkled lids. She spoke more slowly than was her custom, to give weight to her words.

‘You seem to have forgotten one thing! When you walk into Sitex in my place, you walk in there with something they have to take seriously. Power! Whatever they think of your ability, that power is the one thing they cannot ignore. The day you take over from me, after my death, you will be representing your mother, who will have become the single largest stock-holder of Sitex. With her power of attorney you will be controlling twenty-five per cent of the preferred stock and fifteen per cent of the common stock of a multi-million-dollar corporation.’ She paused and stared intently at Paula, and then continued: ‘That’s not ordinary power, Paula. That’s immense power, and especially so in one person’s hands. And don’t you ever forget that. Believe me, they won’t when it comes to the crunch. They didn’t yesterday. But in spite of their unparalleled behaviour – and I am beginning to realize just how much it did upset you – they were unable to ignore me and what I represent!’ Emma sat back in her seat, but she kept her eyes focused on Paula, and her face was implacable.

The girl had been listening attentively to her grandmother, as she always did, and her nervousness was ebbing away. For she did have courage and spirit, and not a little of Emma’s resoluteness. But the virulence of the fighting at Sitex had indeed appalled her, as Emma suspected. As she gazed at her grandmother, reflecting on her words, she marvelled at her again, as she had yesterday. Emma was seventy-eight years old. An old woman. Yet she had none of the infirmities of the aged, nor their loss of grace. She was vital and totally in command of her faculties. Paula had watched her grandmother’s performance at Sitex with awe, had been amazed at her invincible strength, but most of all she had admired her integrity in the face of incredible pressure and opposition. Now Paula wondered, with a cold and calculating objectivity, whether she would ever have that sense of purpose, that icy tenacity to manipulate those men as astutely as her grandmother had. She was not sure. But then some of the nagging doubts were dispelled as she recognized the truth of her grandmother’s words. Finally it was her own driving ambition that ultimately overcame the remnants of nervousness.

She spoke with renewed confidence. ‘You’re right, of course. Power is the most potent of weapons, probably more so than money. And I’m sure it is the only thing the Sitex board do understand.’ She paused and looked at her grandmother directly. ‘I’m not afraid of them! Don’t think that, Grandy. Although I must admit they did disgust me. I suppose if I was afraid, I was afraid of failing you.’ The smile she gave Emma was full of sureness and the troubled look had left her face.

Emma leaned forward and patted her hand reassuringly. ‘Don’t ever be afraid of failing, Paula. It’s stopped more people achieving their goals than I care to think about. When I was your age I didn’t have time to worry about failing. I had to succeed to survive. And always remember what you just said to me about power. It is the ultimate weapon. Power, not money, talks. Money is only important when you’re truly poor, when you need it for a roof over your head, for food and clothes. Once you have these essentials taken care of and go beyond them, money is simply a unit, a tool to work with. And don’t ever let anyone persuade you that power corrupts. It doesn’t always, only when those with power will do anything to hold on to that power. Sometimes it can even be ennobling.’ She smiled briefly and added with great positiveness, ‘And you won’t fail me, my dear.’

‘I hope not, Grandy,’ Paula said, and when she saw the challenging look that swept over Emma’s face, she added quickly, ‘I know I won’t! But what about Harry Marriott? He’s the chairman and he appears to hate me.’

‘I don’t think he hates you, Paula. Fears you perhaps.’ Emma’s voice was suddenly flat, but there was a dark gleam in her eyes. She had many memories of Harry Marriott, none of them very pleasant, for she had crossed swords with him innumerable times in the past.

‘Fears me! Why?’ Surprise made the girl’s voice rise noticeably, and she leaned forward towards her grandmother.

A flicker of contempt touched Emma’s face as she thought of Marriott. ‘Because you remind him too much of your grandfather and that unnerves him. Harry was afraid of your grandfather from the very beginning, when they formed the original Sydney – Texas Oil Company and started drilling. Your grandfather always knew what Harry was and Harry instinctively knew that he knew. Hence his fear. When your grandfather left the Sitex stock to me it was with the understanding that I would never sell it as long as I lived. I was to hold it in trust for your mother and any children she might have. You see, your grandfather had great vision, Paula. He recognized years ago that Sitex would become the major company it is today and he wanted us to benefit from it. And he wanted Harry controlled. He wanted my rein on him always.’

‘I don’t think he can do any more damage at Sitex. He’s been rendered virtually powerless, thanks to you. Grandfather would be proud of you, darling,’ Paula said, and then asked with some curiosity, ‘Do I really resemble him? Grandfather, I mean?’

Emma looked at Paula quickly. They were flying into the sun and a passage of light, very intense and golden, came in through the window. It centred on Paula as she was speaking. To Emma, her hair seemed shinier and blacker in this golden light, hanging in folds like switches of velvet around the pale still face, and her eyes were bluer and more alive than ever. His eyes. His hair. She smiled gently, her eyes lighting up. ‘Sometimes you do, like right now. But mostly I think it’s something in your manner that flusters Harry Marriott. And you have no cause to worry about him, Paula. He won’t be there for long.’ She turned to the briefcase on the seat and began sorting her papers. After a few minutes she looked up and said, ‘If you’ve finished with the balance sheets of the New York store I’ll have them back. By the way, do you agree with me?’

‘Yes, I do, Grandy. They’ve made a marvellous turnaround.’

‘Let’s hope we can keep them on the straight and narrow,’ Emma said as she took the folder from Paula. She put on her glasses and began studying the figures from the Paris store, already calculating the changes that would have to be made there: Emma knew the store was running into trouble and her mouth tightened in aggravation as she concentrated on the damning figures, and considered the moves she would make on their return to England.

Paula poured herself another cup of coffee and, as she sipped it, regarded her grandmother carefully. This is the face I’ve seen all my life and loved all my life, she reflected, a wave of tenderness sweeping through her. And she doesn’t look her age at all, in spite of what she thinks. She could easily pass for a woman in her early sixties. Paula knew that her grandmother’s life had been hard and frequently painful, yet, surprisingly, her face was incredibly well preserved. Paula realized, as she looked at Emma, that this was due in no small measure to the excellence of her bone structure. She noted the webs of wrinkles etching lacy patterns around her grandmother’s eyes and mouth, as well as the two deep lines scoring down from her nostrils to her chin. But she also saw that the cheeks above these lines were still firm, and the green eyes that turned flinty in anger were not the rheumy wavering eyes of an old woman. They were alert and knowing. And yet some of her troubled life is reflected in her face, she thought, observing the indomitable set of Emma’s mouth and the pugnacious tilt of her chin. Paula acknowledged to herself that her grandmother was austere and somewhat stern of eye, to many the basilisk. Yet she was also aware that this autocratic bearing was often softened by a beguiling charm, a sense of humour, and an easy naturalness. And, now that her guard was down, it was a vulnerable face, open and fine and full of wisdom.

Paula had never been afraid of her grandmother, but she recognized that most of the family were, her Uncle Kit in particular. Paula remembered now how delighted she had been when her Uncle Kit had once likened her to Emma. ‘You’re as bad as your grandmother,’ he had said when she was about six or seven years old. She had not fully understood what he had meant, or why he had said it, but she had guessed that it was a reprimand from the look on his face. She had been thrilled to be called ‘as bad as your grandmother’, because surely this meant that she, too, must be special like Grandy and everyone would be afraid of her, as they were afraid of her grandmother.

Emma looked up from the papers. ‘Paula, how would you like to go to the Paris store when we leave New York? I really think I have to make some changes in the administration, from what I see in these balance sheets.’

‘I’ll go to Paris if you want, but to tell you the truth, I had thought of spending some time in Yorkshire, Grandy. I was going to suggest to you that I do a tour of the northern stores,’ Paula remarked, keeping her voice casual and light.

Emma was thunderstruck and she did not attempt to disguise this. She took off her glasses slowly and regarded her granddaughter with a quickening interest. The girl flushed under this fixed scrutiny and her face turned pink. She looked away, dropped her eyes, and murmured, ‘Well, you know I’ll go where you think I’m most needed. Obviously it’s Paris.’ She sat very still, sensing her grandmother’s surprised reaction.

‘Why this sudden interest in Yorkshire?’ Emma demanded. ‘It strikes me there is some fatal fascination up there! Jim Fairley, I presume,’ she added.

Paula shifted in her seat, avoiding her grandmother’s unflickering stare. She smiled falteringly and the flush deepened as she said defensively, ‘Don’t be ridiculous! I just thought I ought to take inventory at the northern stores.’

‘Inventory my eye and Peggy Martin!’ Emma exclaimed, and she thought to herself: I can read Paula like a book. Of course it’s Fairley. Aloud she said, ‘I do know that you are seeing him, Paula.’

‘Not any more!’ Paula cried, her eyes flashing. ‘I stopped seeing him months ago!’ As she spoke she instantly recognized her mistake. Her grandmother had so easily trapped her into admitting the one thing she had vowed she would never admit to her.

Emma laughed softly, but her gaze was steely. ‘Don’t be so upset. I’m not angry. Actually I never was. I only wondered why you never told me. You usually tell me everything.’

‘At first I didn’t tell you because I know how you feel about the Fairleys. That vendetta of yours! And I didn’t want to upset you. God knows, you’ve had enough trouble in you life, without me causing you any more. When I stopped seeing him there seemed to be no point in bringing up something that was finished. I didn’t want to disturb you unnecessarily, that’s all.’

‘The Fairleys don’t upset me,’ Emma snapped. ‘And in case you’ve forgotten, I employ Jim Fairley, my dear. I would hardly have him running the Yorkshire Consolidated Newspaper Company if I didn’t trust him.’ Emma gave Paula a searching glance and asked quickly, curiously, ‘Why did you stop seeing him?’

‘Because I … we … he … because,’ Paula began, and hesitated, wondering whether she dare go on. She did not want to hurt her grandmother. But in her crafty way she’s known about our relationship all the time, Paula thought. The girl drew in her breath and, knowing herself to be trapped, said, ‘I stopped seeing Jim because I found myself getting involved. I knew if I continued to see him it would only mean eventual heartache for me, and for him, and pain for you, too.’ She paused and looked away and then continued with the utmost quiet: ‘You know you wouldn’t accept a Fairley in the family, Grandmother.’

‘I’m not so sure about that,’ Emma said in a voice that was hardly audible. So it went that far, she thought. She felt unutterably weary. Her cheekbones ached and her eyes were scratchy from fatigue. She longed to close her eyes, to be done with this silly and useless discussion. Emma tried to smile at Paula, but her mouth was parched and her lips would not move. Her heart constricted and she was filled with an aching sadness, a sadness she thought had been expunged years ago. The memory of him was there then, so clearly evoked that it bit like acid into her brain. And Emma saw Edwin Fairley as vividly as if he was standing before her. And in his shadow there was Jim Fairley, his spitting image. Edwin Fairley, usually so elusive in her memory, was caught and held and all the pain he had caused her was there, a living thing. A feeling of such oppression overcame her she could not speak.

Paula was watching her grandmother intently and she was afraid for her when she saw the sad expression on that severe face. There was an empty look in Emma’s eyes and, as she stared into space, her mouth tightened into a harsh and bitter line. Damn the Fairleys, all of them, Paula cursed. She leaned forward and took hold of her grandmother’s hand anxiously. ‘It’s over, Grandy. It wasn’t important. Honestly. I’m not upset about it. And I will go to Paris, Grandy! Oh, Grandy darling, don’t look like that, please. I can’t bear it.’ Paula smiled shakily, concerned, afraid, conciliatory. These mingled emotions ran together and underlying them all was a sickening fury with herself for permitting her grandmother to goad her into this ridiculous conversation, one she had been avoiding for months.

After a short time the haunted expression faded from Emma’s face. She swallowed hard and took control of herself, exercising that formidable iron will that was the root of her power and her strength. ‘Jim Fairley’s a good man. Different from the others …’ she began. She stopped and sucked in her breath. She wanted to proceed, to tell Paula she could resume the friendship with Jim Fairley. But she could not. Yesterday was now. The past was immutable.

‘Don’t let’s talk about the Fairleys. I said I would go to Paris,’ Paula cried, clinging to her grandmother’s hand. ‘You know best and perhaps I should look the store over anyway.’

‘I think you must go over there, Paula, to see what’s going on.’

‘I’ll go as soon as we get back to London,’ Paula said swiftly.

‘Yes, that’s a good idea,’ Emma agreed rather brusquely, as glad as Paula to change the subject, but also instinctively pressed for time, as she had been all of her life. Time was a precious commodity to Emma. Time had always been evaluated as money and she did not want to waste it now, dwelling on the past, resurrecting painful events that had taken place some sixty years ago.

Emma said, ‘I think I must go directly to the office when we arrive in New York. Charles can take the luggage to the apartment, after he’s dropped us off. I’m worried about Gaye, you see. Have you noticed anything peculiar when you’ve spoken to her on the phone?’

Paula was sitting back in her seat, relaxed and calm again, relieved that the subject of Jim Fairley had been dropped. ‘No, I haven’t. What do you mean?’

‘I can’t pin it down to anything specific,’ Emma continued thoughtfully, ‘but instinctively I know something is dreadfully wrong. She has sounded edgy during all of our conversations. I noticed it the day she arrived from London and called me at Sitex. Haven’t you detected anything in her voice?’

‘No. But then she has been speaking mostly to you, Grandmother. You don’t think there is some trouble with the business in London, do you?’ Paula asked, alarmed.

‘I sincerely hope not,’ Emma said, ‘that’s all I need after the Sitex situation.’ She drummed her fingers on the table for a few moments and then looked out of the window, her mind awash with thoughts of her business and her secretary, Gaye Sloane. In her sharp and calculating way she enumerated all of the things that could have gone wrong in London and then gave up. Anything might have happened and it was futile to speculate and hazard wild guesses. That, too, was a waste of time.

She turned to Paula and gave her a wry little smile. ‘We’ll know soon enough, my dear. We should be landing shortly.’

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_d51c9800-fe45-5f1c-b911-696d744d3a2c)

The American corporate offices of Harte Enterprises took up six floors in a modern office block on Park Avenue in the Fifties. If the English department-store chain Emma Harte had founded years ago was the visible symbol of her success, then Harte Enterprises was the living heart and sinew. An enormous octopus of an organization, with tentacles that stretched half around the world, it controlled clothing factories, woollen mills, real estate, a retail merchandise company, and newspapers in England, plus large blocks of shares in other major English companies.

As the original founder of this privately held corporation, Emma still owned 100 per cent of the shares of Harte Enterprises, and it operated solely under her aegis, as did the chain of department stores that bore her name, with branches in the North of England, London, Paris, and New York. Harte Stores was a public company, trading on the London Stock Exchange, although Emma was the majority shareholder and chairman of the board. The diversified holdings of Harte Enterprises in America included real estate, a Seventh Avenue dress-manufacturing company, and other stock investments in American industries.

Whilst Harte Stores and Harte Enterprises were worth millions of pounds, they represented only a portion of her fortune. Apart from owning 40 per cent of the stock in the Sitex Oil Corporation of America, she had vast holdings in Australia, including real estate, mining, coal fields, and one of the largest fully operating sheep stations in New South Wales. In London, a small but rich company called E.H. Incorporated controlled her personal investments and real estate.

It had been Emma’s custom to travel to New York several times a year. She was actively involved in all areas of her business empire and although she was not particularly distrustful of those to whom she had given extraordinary executive powers, confident of her own shrewd judgement in these choices, there was a canny Yorkshire wariness about her. She was impelled to leave nothing to chance and she also believed that it was vital for her presence to be felt in New York from time to time.

Now, as the Cadillac that had brought them from Kennedy Airport pulled up in front of the skyscraper that housed her corporate offices, Emma’s thoughts reverted to Gaye Sloane. Emma had instantly detected Gaye’s nervousness during their first telephone conversation when she had arrived from London. Originally Emma had thought this was due to tiredness after the long transatlantic flight, but the nervousness had accelerated rather than diminished over the last few days. Emma had noted the tremulous quality in Gaye’s voice, her clipped manner, her obvious desire to terminate their talks as quickly as possible. This not only baffled Emma but disturbed her, for Gaye was behaving totally out of character. Emma contemplated the possibility that personal problems might be upsetting Gaye, but her inclination was to dismiss this idea, knowing Gaye as well as she did. Intuitively Emma knew that Gaye was troubled by a business problem, one which was of some import and one which ultimately affected her. She resolved to make her talk with Gaye the priority of the day’s business.

Emma shivered as they alighted from the car. It was a raw January day, and although the sun was bright in a clear sky, the wind was sharp with frost and Atlantic rain. She could barely remember a time when she had not felt ice cold all over and sometimes it seemed to her that her bones were frozen into solid blocks of ice, as if frostbite had crept into her entire being and petrified her very blood. That numbing excruciating coldness that had first invaded her body in childhood had rarely left her since, not under the heat of tropical sun nor in front of blazing fires nor in the central heating of New York, which she usually found suffocating. She coughed as she and Paula hurried towards the building. She had caught a cold before they had left for Texas and it had settled on her chest, leaving her with this hacking cough that flared up constantly. As they swung through the doors into the building, Emma was for once thankful for that furnace-like heating in her offices.

They took the elevator up to the thirtieth floor, where their own offices were located. ‘I think I had better see Gaye at once, and alone,’ Emma said as they stepped out. ‘Why don’t you go over the balance sheets of the New York store with Johnston and I’ll see you later,’ she suggested.

Paula nodded. ‘Fine. Call me if you need me. Grandmother. And I do hope everything is all right.’ Paula veered to the left as Emma continued on to her own office, moving through the reception area quickly and with agility. Emma smiled at the receptionist, and exchanged cordial greetings with her as she swept through the double doors that led to her private domain. She closed the doors firmly behind her, for she did not subscribe to this American custom of open doors in executive offices. She thought it peculiar and distracting, addicted as she was to total privacy. She threw her tweed coat and her handbag carelessly on to one of the sofas and, still holding the briefcase, she crossed the room to the desk. This was a gargantuan slab of heavy glass on a simple base of polished steel, a dramatic focal point in the highly dramatic office. It was angled across a corner, looking out into the vast and lovely room, facing towards a plate-glass window. This covered the whole of one wall and rose to the ceiling in a glittering sweep that presented a panoramic view of the city skyline, which Emma always thought of as a living painting of enormous power and wealth and the heartbeat of American industry.

She enjoyed her New York office, different as it was from her executive suite in the London store, which was filled with the mellow Georgian antiques she preferred. Here the ambiance was modern and sleek, for Emma had a great sense of style and she had decided that as much as she loved period furniture, it would be unfitting when juxtaposed against the slick architecture of this great steel-and-glass structure that pushed its way up into the sky. And so she had assembled the best in modern furniture design. Mies van der Rohe chairs were mingled with long, slender Italian sofas, all of them upholstered in dark leather as soft and as supple as silk. There were tall steel-and-glass étagères filled with books, cabinets of rich polished rosewood, and small tables made of slabs of Italian marble balanced on polished chrome bases. Yet for all of its modern overtones there was nothing austere or cold about the office, which had a classical elegance and was the epitome of superior taste. It had, in fact, a tranquil beauty, a softness, filled as it was with a misty mélange of intermingled blues and greys, these subdued tones washing over the walls and the floor, enlivened here and there by rafts of more vivid colours in the cushions on the sofas and in the priceless French Impressionist paintings which graced the walls. Emma’s love of art was also evidenced in the Henry Moore and Brancusi sculptures and the temple heads from Angkor Wat, which were displayed on black marble pedestals around the room. The great soaring window was sheathed in sheer bluish-grey curtains which fell like a heavy mist from the ceiling, and when they were open, as they were now, the room seemed to be part of the sky, as if it was suspended in space above the towering concrete monoliths of Manhattan.

Emma smiled as she sat down at the desk, for Gaye’s handiwork was apparent. The long sweep of glass was neat and uncluttered, just the way she liked it, bare except for the telephones, the silver mug of pens, the yellow legal pad she favoured for notes, and the practical metal extension lamp that flooded the desk with light. Her correspondence, interoffice memos, and a large number of telexes were arranged in respective files, while a number of telephone messages were clipped together next to the telephones. She took out her glasses and read the telephone messages and the telexes, making various notations on these, and then she buzzed for Gaye. The minute she entered the room Emma knew that her fears had not been unfounded. Gaye was haggard and she had dark smudges under her eyes and seemed to vibrate with tension. Gaye Sloane was a woman of about thirty-eight and she had been Emma’s executive secretary for six years although she had been in her actual employ for twelve years. She was a model of diligence and efficiency and was devoted to Emma, whom she not only admired but held in considerable affection. A tall well-built woman with an attractive appearance, she was always self-contained, usually in command of herself.

But as she walked across the room Emma detected raw nerves barely controlled. They exchanged pleasantries and Gaye sat down in the chair opposite Emma’s desk, her pad in her hand.

Emma sat back in her chair, consciously adopting a relaxed attitude in an effort to make Gaye feel as much at ease as possible. She glanced at her secretary kindly and asked quietly, ‘What’s wrong, Gaye?’

Gaye hesitated momentarily and then said rather hurriedly, feigning surprise, ‘Why, nothing, Mrs Harte. Truly, I’m just tired. Jet lag, I think.’

‘Let’s forget about jet lag, Gaye. I believe you are extremely upset and have been since you arrived in New York. Now come along, my dear, tell me what’s bothering you. Is it something here or is there a problem with business in London?’

‘No. Of course not!’ Gaye exclaimed, but she paled slightly and looked away, avoiding Emma’s steady gaze.

Emma leaned forward, her arms on the desk, her eyes glittering behind her glasses. She became increasingly conscious of the woman’s suppressed emotions and sensed that Gaye was troubled by something of the most extreme seriousness. As she continued to study her she thought Gaye seemed close to total collapse.

‘Are you ill, Gaye?’

‘No, Mrs Harte. I’m perfectly well, thank you.’

‘Is something in your personal life disturbing you?’ Emma now asked as patiently as she could, determined to get to the root of the problem.

‘No, Mrs Harte.’ Her voice was a whisper.

Emma took off her glasses and gave Gaye a long, piercing look and said briskly, ‘Come, come, my dear! I know you too well. There is something weighing on your mind and I can’t understand why you won’t tell me about it. Have you made some sort of mistake and are afraid to explain? Surely not after all these years. Nobody is infallible and I’m not the ogre I’m supposed to be. You, of all people, should know that by now.’

‘Oh, I do, Mrs Harte …’ The girl broke off. Her voice was shaking and she was close to tears.

The woman sitting opposite Gaye was composed and in absolute control of herself. She was no weakling, Gaye knew that only too well. She was tough and resilient, an indomitable woman who had achieved her phenomenal success because of her formidable character and her strength of will, plus her resourcefulness and brilliance in business. To Gaye, Emma Harte was as indestructible as the coldest steel that could not be twisted or broken. But I am about to break her now, she thought, panic taking hold of her again.

Emma had seen, with gathering disquiet, the twitching muscles and the fear in her eyes. She stood up decisively and crossed the room to the rosewood bar, shaking her head in perplexity. She opened the bar, poured a measure of cognac into a small glass, and brought it back to Gaye.

‘Drink this, my dear. It will make you feel better,’ she said, patting the woman’s arm affectionately.

Tears sprang into Gaye’s eyes and her throat ached. The brandy was harsh and it stung her throat but she was suddenly glad of its rough taste. She sipped it slowly and remembered Emma’s kindnesses to her over the years. At that precise moment she wished, with great fervency, that she was not the one who had to impart this news. Gaye realized that there were those, who had dealt with Emma as a formidable adversary, who considered her to be cynical, rapacious, cunning, and ruthless. On the other hand, Gaye knew that she was generous of her time and money and understanding of heart. As she was being understanding now. Perhaps Emma was wilful and imperious and even power-ridden. But surely life had made her so. Gaye had always said to Emma’s critics, and with the utmost veracity, that above all the other tycoons of her calibre and stature, Emma Harte had compassion, and was just and charitable and infinitely kind.

Gaye eventually became aware of this prolonged silence between them, of Emma’s fixed stare. She put the glass down on the edge of the desk and smiled weakly at Emma. ‘Thank you, Mrs Harte. I do feel better.’

‘Good. Now Gaye, why don’t you confide in me? It can’t be all that terrible.’

Gaye was paralysed, unable to speak.

Emma shifted in her seat and leaned forward urgently. ‘Look here, is this something to do with me, Gaye?’ Her voice was calm and strong.

It seemed to give Gaye a degree of confidence. She nodded her head and was about to speak, but when she saw the look of concern enter Emma’s eyes, her courage deserted her again. She put her hands up to her face and cried involuntarily, ‘Oh God! How can I tell you!’

‘Let’s get it out in the open, Gaye. If you don’t know where to begin, then begin in the middle. Just blurt it out. It’s often the best way to talk about something unpleasant, which I presume this is.’

Gaye nodded and began hesitatingly, choking back her tears, her hands twitching nervously, her eyes staring and wide. She spoke rapidly in bursts, wanting to tell it all now, and get it over as quickly as possible. It would be a relief, for it had preyed on her mind for days.

‘It was the door … I remembered … I went back … I heard them talking … No, shouting … they were angry … arguing … they were saying …’

‘Just a minute, Gaye.’ Emma held up her hand to stop the incoherent flow of words. ‘I don’t want to interrupt you, but can you try to be a little more explicit. I know you’re upset, but slow down and take it calmly. What door?’

‘Sorry.’ Gaye drew a deep breath. ‘The door of the filing room that opens on to the boardroom in London. I’d forgotten to lock it last Friday night. I was leaving the office and I remembered I had forgotten to turn off the tape machine, and that reminded me of the door. I went back to my office, because I was leaving on Saturday night for New York. I unlocked the door at my side and walked through the filing room to lock the door at the other end.’

As Gaye had been speaking Emma had a mental image of the filing room in the executive suite of offices in the London store. It was a long narrow room with filing cabinets banked on either side and rising to the ceiling. A year ago, Emma had broken through the back wall of the filing room into the adjoining boardroom and added a door. This measure had been to facilitate easy access to documents that might be needed at board meetings, but it had also turned out to be a useful little artery that linked the boardroom and the executive offices and so saved a great deal of time.

Innumerable questions ran through Emma’s mind, but she reserved them for later. She nodded for her secretary to continue.

‘I know how particular you are about that door being locked, Mrs Harte. As I walked through the filing room from my office I noticed that the door was not simply unlocked but actually open … ajar. That’s when I heard them … through the crack in the door. I didn’t know what to do. I was afraid they would hear me closing and locking the door. I didn’t want anyone to think I was eavesdropping. So I stopped for a moment, and then I turned off the light, so they wouldn’t know I was in the filing room. Mrs Harte, I …’ Gaye paused and swallowed, momentarily unable to continue.

‘Go on, Gaye, it’s all right.’

‘I wasn’t eavesdropping, I really wasn’t, Mrs Harte. You know I’m not like that. It was purely accidental … that I heard them, I mean. I heard them say … say …’

Gaye stopped again, shaking all over. She looked at Emma, who was sitting perfectly rigid in her chair, her face an unreadable mask.

‘I heard them say, no, one of them said that you were getting too old to run the business. That it would be hard to prove that you were senile or incompetent, but that you would agree to step down to avoid a scandal, to prevent a catastrophe with the Harte shares on the Stock Exchange. They argued about this. And then he, that is, the one who had been doing most of the talking, said that the stores had to be sold to a conglomerate and that this would be easy as several companies would be interested in a take-over. He then said that Harte Enterprises could be sold off in pieces …’ Gaye hesitated, and looked closely at Emma in an attempt to discern her reactions. But Emma’s face was still inscrutable.

The sun came out from behind a bank of grey clouds and streamed into the room, a great cataract of brilliant light that was harsh and unrelenting, flooding that vast space with a white brilliance that made the room look alien, unreal, and frightful to Emma. She blinked and shielded her eyes against it.

‘Could you close the curtains please, Gaye,’ she murmured, her voice a hoarse whisper.

Gaye flew across the room and pushed the automatic button that operated the curtains. They swept across the soaring window with a faint swishing sound and the penetrating radiance in the room was softly diffused. She returned to her chair in front of the desk and, gazing at Emma, she asked with some concern, ‘Are you all right, Mrs Harte?’

Emma had been staring at the papers on her desk. She lifted her head slowly and looked across at Gaye with blank eyes. ‘Yes. Please go on. I want to know all of it. And I am perfectly sure there is more.’

‘Yes, there is. The other one said it was futile to battle with you now, either personally or legally, that you couldn’t live much longer, that you were getting old, very old, almost eighty. And the other one said you were so tough they would have to shoot you in the end.’ Gaye covered her mouth with her hand to stifle a sob and tears pricked her eyes. ‘Oh, Mrs Harte, I’m so sorry.’

Emma was so still she might have turned to stone. Her eyes were suddenly cold and calculating. ‘Are you going to tell me who these two gentlemen were, Gaye? Mind you, I use that term loosely,’ she said with biting sarcasm. Before Gaye had a chance to reply Emma knew deep within herself, deep down in the very marrow of her bones, exactly whom Gaye would condemn when she opened her mouth. And yet part of her was still disbelieving, still hopeful, and she must hear it from Gaye’s own mouth to truly believe it. To accept her own damning suspicions as fact.

‘Oh God, Mrs Harte! I wish I didn’t have to tell you this!’ She took a deep breath. ‘It was Mr Ainsley and Mr Lowther. They started to quarrel again, and Mr Lowther said that they needed the girls with them. Mr Ainsley said the girls were with them, that he already talked to them. But that he had not talked to Mrs Amory, since she would never agree. He said she must not be told anything, under any circumstances, because she would immediately run and tell you. Mr Lowther then said again that there was nothing they could do about taking over the business whilst you were still alive. He told Mr Ainsley that they would never get away with it, because they did not have the power, or enough shares between them, to gain control. He said they would just have to wait until you were dead. He was adamant about this. He also told Mr Ainsley that he himself was entitled to the controlling shares of the Harte chain and that he was certain you would leave them these shares. He then informed Mr Ainsley that he intended to run the Harte chain and that he would never agree to sell the stores to a conglomerate. Mr Ainsley was furious, almost hysterical, and started to scream the most terrible things at Mr Lowther. But Mr Lowther eventually calmed him down, and he said he would agree to the sale of Harte Enterprises, and that would bring Mr Ainsley all the millions he wanted. Mr Ainsley then asked if Mr Lowther knew what was in your will. Mr Lowther told him he didn’t know, but that he thought you would be fair with them all. He did express some concern about Miss Paula, because she was so close to you. He said he didn’t know what she had been able to wheedle out of you. This upset Mr Ainsley, and he grew very excited again and said that they must formulate a plan of action now, one which they could put into operation after your death, in the event that your will did not favour them.’

Gaye paused breathlessly, poised on the edge of her chair.

Emma could not speak or move or think, so stunned and shaken was she now. As she reflected on Gaye’s words the blood rushed to her head and a faintness settled over her. Every bone in her body felt weighted down by the most dreadful fatigue, a fatigue that was leaden and stupefying.

Her heart shifted within her, and it seemed to Emma that in that instant it withered and turned into a cold, hard little pebble. An immense pain flooded her entire being. It was the pain of despair. The pain of betrayal. Her two sons were plotting against her. Robin and Kit. Half brothers who had never been close were now hand in glove, partners in treachery. She was incredulous as she thought: God Almighty! It’s not possible. It can’t be possible. Not Kit. Not Robin. They could never be so venal. Never. Not my boys! Yet somewhere in the recesses of her mind, in her innermost soul, she knew that it was true. And that anguish of heart and soul and body was displaced by an anger of such icy ferocity that it cleared her brain and propelled her to her feet. Dimly, distantly, she heard Gaye’s voice coming to her as if from a cavernous depth.

‘Mrs Harte! Mrs Harte! Are you ill?’

Emma leaned forward across the desk, which she gripped tightly to steady herself, and her face was drawn and pinched. Her voice was low as she said, ‘Are you sure of all this, Gaye? I don’t doubt you, but are you certain you heard everything correctly? You realize the seriousness of what you have recounted, I’m sure, so think very carefully.’

‘Mrs Harte, I am absolutely sure of everything I’ve said,’ Gaye answered quietly. ‘Furthermore, I have not added or subtracted anything, and I haven’t exaggerated either.’

‘Is that all?’

‘No, there’s more.’ Gaye bent down and picked up her handbag. She opened it and took out a tape, which she placed on the desk in front of Emma.

Emma regarded the tape, her eyes narrowing. ‘What is this?’

‘It’s a tape of everything that was said, Mrs Harte. Except for whatever occurred before I went into the filing room. And the first few sentences I heard. They are missing.’

Emma looked at her uncomprehendingly, her eyebrows lifting, questions on the tip of her tongue. But before she could ask them, Gaye proceeded to explain more fully.

‘Mrs Harte, the tape machine was on. That’s why I went back to the office in the first place. When I went into the filing room, and heard them shouting, I was distracted for a minute. I turned off the filing-room light so they wouldn’t come in and see me. It was then that I saw the red light on the machine flickering and I went to turn this off, too. But it suddenly occured to me to record their conversation, since I was getting the general drift of it, and realized its importance. So I pressed the record button. Everything they said after that moment is here, even the things which were said after I closed the door and couldn’t hear clearly.’

Emma had the irresistible desire to laugh out loud, a bitter, hollow laugh. She resisted the impulse, lest Gaye think her raving mad and out of her senses, or hysterical at the most. The fools, the utter fools! she thought. And the irony of it! They had chosen her own boardroom in which to plot against her. That was their first and most crucial mistake. An irrevocable mistake. Kit and Robin were directors of Harte Enterprises, but they were not on the board of the department-store chain. They did not come to board meetings at the store, and so they did not know that she had recently installed sophisticated equipment to record the minutes, another time-saving device. It liberated Gaye for other duties and she simply typed up the minutes from the tapes when it was convenient. The microphones were hooked up under the boardroom table, hidden for aesthetics rather than for any reasons of secrecy in the elegant Georgian room with its fine antiques and paintings of great worth. Emma looked down at the tape on the glass desk, and to her it was an evil thing, lying there like a coiled and venomous snake.

‘I assume you have listened to this, Gaye?’

‘Yes, Mrs Harte. I waited until they left and then I played it back, I took it home with me on Friday and it hasn’t been out of my sight since then.’

‘Is there much more on it? More than you have already told me?’

‘About another ten minutes or so. They were discussing …’

Emma held up her hand, utterly exhausted, unable to hear any more. ‘Never mind, Gaye. I’ll play it later. I know quite enough already!’

She stood up and walked across the room to the window, erect and composed, though her steps were slow and dragged wearily across the thick carpet. She moved the curtains slightly. It had started to snow. The crystal flakes fell in glittering white flurries, swirling and eddying in the wind, brushing up against the window and coating it with a light film as delicate and as fine as white lace. But the flakes were rapidly melting under the bright sun, running in rivulets down the glass and turning into drizzle before they reached the ground. Emma looked down. Far below her the traffic moved in slow unending lines up and down Park Avenue and the scene was strangely remote. And everything was hushed in the room, as if the entire world had stopped and was silent, stilled for ever.

She pressed her aching head against the window and closed her eyes and thought of her two sons, of all her children, but mostly of her adored Robin, her favourite son. Robin, who had become her antagonist after they had clashed a few years before about a take-over bid for the chain of stores. A bid which came from out of the blue and which she did not want to even discuss, never mind consider. When she had refused to talk to the conglomerate involved, he had been vociferous in his condemnation of her, exclaiming angrily that she did not want to sell because she did not want to relinquish her power. She had met resentment from him in such virulent proportions that she was at first incredulous and then truly infuriated. What nerve, what gall, she had thought at the time, that he would dare to dictate to her about her business. One in which he did not have the slightest interest, except for the money it brought him. Robin the handsome, the dashing, the brilliant Member of Parliament. Robin with his long-suffering wife, his mistresses, his rather questionable male friends, and his taste for high living. Yes, Robin was the instigator of this deadly little plot, of that she was quite sure.

Kit, her eldest son, did not have the imagination or the nerve to promulgate so nefarious a scheme. But what he lacked in imagination he made up for in plodding diligence and stubbornness and he was uncommonly patient. Kit could wait years for anything he truly wanted, and she had always known he wanted the stores. But he had never had any aptitude for retailing, and long ago, when he was still young, she had manoeuvred him into Harte Enterprises, steered him towards the woollen mills in Yorkshire, which he ran with a degree of efficiency. Yes, Kit could always be manoeuvred, and no doubt Robin is doing just that, she thought contemptuously.

She contemplated her three daughters and her mouth twisted into a grim smile as she considered Edwina, the eldest, the first born of all her children. She had worked like a drudge and fought like a tigress for Edwina when she was still only a girl herself, for she had loved Edwina with all her heart. And yet she had always known that Edwina had never truly felt the same way about her, oddly distant as a little girl, remote in her youth, and that remoteness had turned into real coldness in later years. Edwina had allied herself with Robin at the time of the take-over bid, backing him to the hilt. Undoubtedly she was now his chief ally in this perfidious scheme. She found it hard to believe that Elizabeth, Robin’s twin, would go along with them, and yet perhaps she would. Beautiful, wild, untameable Elizabeth, with her exquisite features and beguiling charm and her penchant for expensive husbands, expensive clothes, and expensive travel. No amount of money was ever enough to satisfy her and she needed it as constantly and as desperately as Robin.

Daisy was the only one of whom she was sure, because she knew that of all her children Daisy truly loved her. Daisy was not involved in this scheme of things, because she would never be a party to a conspiracy engineered by her brothers and sisters to slice up the Harte holdings. Apart from her love and her loyalty, Daisy had the utmost respect for her and faith in her judgement. Daisy never questioned her motives or decisions, because she recognized that they were generated by a sense of fair play, and were based entirely on judicious planning.

Daisy was her youngest child, and as different in looks and character from Emma as the others were, but she was closely bound to her mother and they cared for each other with a deep and powerful love that bordered on adoration. Daisy was all sweetness and gentleness, fine and honourable and good. At times, in the past, Emma had mused on Daisy’s intrinsic purity and honesty and worried about it, believing her to be too open and soft for her own safety. Emma had reasoned that her goodness could only make her dangerously vulnerable. But, eventually, she had begun to comprehend that there was a deep and strong inner core in Daisy that was tenacious. In her own way she could be as implacable as Emma, and she was unshakeable in her beliefs, brave and courageous in her actions, and steadfast in her loyalties. Emma had finally recognized that it was Daisy’s very goodness that protected her. It enfolded her like a shining and impenetrable sheath of chain mail and so made her incorruptible and inviolate against all.