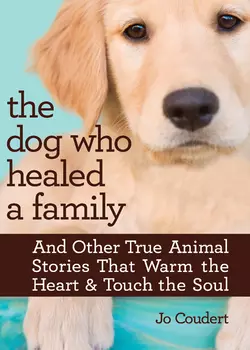

The Dog Who Healed A Family

The Dog Who Healed A Family

Jo Coudert

In this charming collection of nineteen stories, you can't help but fall in love with the unlucky fawn who is saved by a nursing home, the troublesome rabbit who warms her way into a new family and the good (German) shepherd who comforts the sick.These are stories of hope, humor, triumph, loyalty, compassion, life and even death—but most of all, these are stories of love and the extraordinary animals who make our lives the richer for it.

the

dog who

healed

a family

And Other True Animal

Stories That Warm the

Heart & Touch the Soul

Jo Coudert

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

Preface

All the stories in this book are about animals, and all are true. What the stories have in common is the love and caring that can exist between animals and people. Nancy Topp struggled for weeks to get a seventeen-year-old dog home across fifteen hundred miles. Gene Fleming fashioned shoes for a goose born without feet and supported the goose in a harness until he learned to walk. Months after their javelina disappeared, Patsy and Buddy Thorne were still roaming ranch lands in Texas, Bubba’s favorite chocolate in their pockets, searching for their wild pig.

The Thornes recently sent a clipping from their local newspaper describing how a group of men out hunting with bows and arrows came upon a javelina. The animal stood still, gazing at the men, while they shot at it three times. When all three arrows failed to strike home, one of the men ventured close enough to pet the animal and found it was tame and welcomed the attention.

What is amazing about the report is not that the animal was Bubba—it was not—but that the hunters shot three times at a creature that was not big enough or wild enough to be a threat to them and that did not provide sport by running. And because the meat of a javelina is too strong-tasting to be palatable, they were not interested in it for food.

The hunters shot at the javelina because it was there, which is the same reason a neighbor who lives downriver from me catches all the trout within hours of the time the state fish and wildlife service stocks the stream. An amiable man who loves his grandchildren, the neighbor has built the children a tree platform where they can sit silently and shoot at the deer who come to the river to drink at twilight. He also sets muskrat traps in the river and runs over woodchucks and possums on the road.

The family doesn’t eat the deer; the frozen body of a doe has been lying all winter in the field in back of my woods. Nor does anyone eat the trout the man catches; he tosses them into a little pond on his property where they stay until they become too numerous and die from lack of oxygen. When I once asked this ordinary, pleasant fellow why he’d gone out of his way to run over a raccoon crossing the road, he looked at me in surprise. “It’s an animal!” he said as though that quite explained it.

To many people it is sufficient explanation. After all, did not Jehovah tell Noah and his sons that all the beasts of the earth and fish of the sea were delivered into the hands of man? Surely this is a license to destroy them even if we have no better reason at the time than the fact that they exist and we wish to.

Or is it? Belatedly we are beginning to realize that the duality of people and animals, us and them, is false, just as we have discovered that there is no split between us and the world. The world is us and we are the world. We cannot simply exploit and destroy, either the world or the animals in it, if we are not at the same time to do ourselves irreparable harm.

Consider what a Native American, Chief Seattle, said in 1854: “What is man without the beasts? If all the beasts were gone, man would die from a great loneliness of spirit. For whatever happens to the beasts, soon happens to man. All things are connected. This we know: The Earth does not belong to man; man belongs to the Earth. This we know: All things are connected like the blood which unites one family. All things are connected. Whatever befalls the Earth befalls the sons of the Earth. Man did not weave the web of life. He is merely a strand in it. Whatever he does to the web, he does to himself.”

The world belongs to the animals just as much as to us. Let us be unselfish enough to share it with them openly and generously. Which is to say, when you come upon a lost dog or an orphaned fawn or a goose born without feet, give it nothing to fear from you, grant it safety, offer to help if you can, be kind. In return, as the stories here show, you will sometimes find a welcome companionship, and surprisingly often love.

Jo Coudert

Califon, New Jersey

The Puppy Express

Curled nose to tail, the little dog was drowsing in Nancy Topp’s lap as the truck rolled along the interstate. Suddenly Nancy felt her stiffen into alertness. “What’s the matter, old girl?” Nancy asked. At seventeen, Snoopy had a bit of a heart condition and some kidney problems, and the family was concerned about her.

Struggling to her feet, the dog stared straight ahead. She was a small dog, with a dachshund body but a beagle head, and she almost seemed to be pointing. Nancy followed the dog’s intent gaze, and then she saw it, too. A wisp of smoke was curling out of a crack in the dashboard. “Joe!” she shouted at her husband at the wheel. “Joe, the engine’s on fire!”

Within seconds the cab of the ancient truck was seething with smoke. Nancy and Joe and their two children—Jodi, twelve, and Matthew, fifteen—leaped to the shoulder of the road and ran. When they were well clear, they turned and waited for the explosion that would blow everything they owned sky-high. Instead, the engine coughed its way into silence, gave a last convulsive shudder and died.

Joe was the first to speak. “Snoopy,” he said to the little brown and white dog, “you may not hear or see so good, but there’s nothing wrong with your nose.”

“Now if you could just tell us how we’re going to get home,” Matthew joked. Except it wasn’t much of a joke. Here they were, fifteen hundred miles from home, stranded on a highway in Wyoming, with the truck clearly beyond even Joe’s gift for repairs. The little dog, peering with cataract-dimmed eyes around the circle of faces, seemed to reflect their anxiety.

The Topps were on the road because five months earlier a nephew had told Joe there was work to be had in the Napa Valley and Joe and Nancy decided to take a gamble on moving out there. Breaking up their home in Fort Wayne, Indiana, they packed up the kids and Snoopy and set out for California. But once there, the warehousing job Joe hoped for did not materialize, Nancy and the kids were sharply homesick and their funds melted away. Now it was January and, the gamble lost, they were on their way back home to Fort Wayne.

The truck had gotten them as far as Rock Springs, Wyoming, but now there was nothing to do but sell it to a junk dealer for $25 and hitch a ride to the bus station. Two pieces of bad news greeted them there. Four tickets to Fort Wayne came to more money than they had, much more, and dogs were not allowed on the bus.

“But we’ve got to take Snoopy with us,” Nancy pleaded with the ticket seller, tears welling in her eyes. It had been a disastrous day, but this was the worst news of all.

Joe drew her away from the window. It was no use getting upset about Snoopy, he told her, until they figured out how to get themselves on the bus. With no choice but to ask for help, they called Travelers Aid, and with kind efficiency the local representative arranged for a motel room for them for the night. There, with their boxes and bags piled in a corner, they put in a call to relatives back home, who promised to get together money for the fare and wire it the next day.

“But what about Snoopy?” Matthew said as soon as his father hung up the phone.

“We can’t go without Snoopy,” Jodi stated flatly.

Joe picked up the little dog. “Snoopy,” he said, tugging her floppy ears in the way she liked, “I think you’re going to have to hitchhike.”

“Don’t tease, Joe,” Nancy said curtly.

“I’m not teasing, honey,” he assured her, and tucked Snoopy into the crook of his arm. “I’m going to try to find an eastbound truck to take the old girl back for us.”

At the local truck stop, Joe sat Snoopy on a stool beside him while he fell into conversation with drivers who stopped to pet her. “Gee, I’d like to help you out,” one after another said. “She’s awful cute and I wouldn’t mind the company, but I’m not going through Fort Wayne this trip.” The only driver who might have taken her picked Snoopy up and looked at her closely. “Naw,” the man growled, “with an old dog like her, there’d be too many pit stops. I got to make time.” Still hopeful, Joe tacked up a sign asking for a ride for Snoopy and giving the motel’s phone number.

“Somebody’ll call before bus time tomorrow,” he predicted to the kids when he and Snoopy got back to the motel.

“But suppose nobody does?” Jodi said.

“Sweetie, we’ve got to be on that bus. The Travelers Aid can only pay for us to stay here one night.”

The next day Joe went off to collect the wired funds while Nancy and the kids sorted through their possessions, trying to decide what could be crammed into the six pieces of luggage they were allowed on the bus and what had to be left behind. Ordinarily Snoopy would have napped while they worked, but now her eyes followed every move Nancy and the children made. If one of them paused to think, even for a minute, Snoopy nosed at the idle hand, asking to be touched, to be held.

“She knows,” Jodi said, cradling her. “She knows something awful is going to happen.”

The Travelers Aid representative arrived to take the belongings they could not pack, for donation to the local thrift shop. A nice man, he was caught between being sympathetic and being practical when he looked at Snoopy. “Seventeen is really old for a dog,” he said gently. “Maybe you just have to figure she’s had a long life and a good one.” When nobody spoke, he took a deep breath. “If you want, you can leave her with me and I’ll have her put to sleep after you’ve gone.”

The children looked at Nancy but said nothing; they understood there wasn’t any choice, and they didn’t want to make it harder on their mother by protesting. Nancy bowed her head. She thought of all the walks, all the romps, all the picnics, all the times she’d gone in to kiss the children good-night and Snoopy had lifted her head to be kissed, too.

“Thank you,” she told the man. “It’s kind of you to offer. But no. No,” she repeated firmly. “Snoopy’s part of the family, and families don’t give up on each other.” She reached for the telephone book, looked up kennels in the yellow pages and began dialing. Scrupulously she started each call with the explanation that the family was down on their luck. “But,” she begged, “if you’ll just keep our little dog until we can find a way to get her to Fort Wayne, I give you my word we’ll pay. Please trust me. Please.”

A veterinarian with boarding facilities agreed finally to take her, and the Travelers Aid representative drove them to her office. Nancy was the last to say goodbye. She knelt to take Snoopy’s frosted muzzle in her hands. “You know we’d never leave you if we could help it,” she whispered, “so don’t give up. Don’t you dare give up. We’ll get you back somehow, I promise.”

Once back in Fort Wayne, the Topps found a mobile home to rent, one of Joe’s brothers gave them his old car, sisters-in-law provided pots and pans and bed linens, the children returned to their old schools and Nancy and Joe found jobs. Bit by bit the family got itself together. But the circle had a painful gap in it. Snoopy was missing. Every day Nancy telephoned a different moving company, a different trucking company, begging for a ride for Snoopy. Every day Jodi and Matthew came through the door asking if she’d had any luck and she had to say no.

By March they’d been back in Fort Wayne six weeks and Nancy was in despair. She dreaded hearing from Wyoming that Snoopy had died out there, never knowing how hard they’d tried to get her back. One day a friend suggested she call the Humane Society. “What good would that do?” Nancy said. “Aren’t they only concerned about abandoned animals?” But she had tried everything else, so she telephoned Rod Hale, the director of the Fort Wayne Department of Animal Control, and told him the story.

“I don’t know what I can do to help,” Rod Hale said when she finished. “But I’ll tell you this. I’m sure going to try.” A week later, he had exhausted the obvious approaches. Snoopy was too frail to be shipped in the unheated baggage compartment of a plane. A professional animal transporting company wanted $655 to bring her east. Shipping companies refused to be responsible for her. Rod hung up from his latest call and shook his head. “I wish the old-time Pony Express was still in existence,” he remarked to his assistant, Skip Cochrane. “They’d have passed the dog along from one driver to another and delivered her back home.”

“It’d have been a Puppy Express,” Skip joked.

Rod thought for a minute. “By golly, that may be the answer.” He got out a map and a list of animal shelters in Wyoming, Nebraska, Iowa, Illinois and Indiana, and picked up the phone. Could he enlist enough volunteers to put together a Puppy Express to transport Snoopy by stages across five states? Would people believe it mattered enough for a seventeen-year-old dog to be reunited with her family that they’d drive a hundred or so miles west to pick her up and another hundred or so miles east to deliver her to the next driver?

In a week he had his answer, and on Sunday, March 11, he called the Topps. “How are you?” he asked Nancy.

“I’d feel a lot better if you had some news for me.”

“Then you can begin feeling better right now,” Rod told her jubilantly. “The Puppy Express starts tomorrow. Snoopy’s coming home!”

Monday morning, in Rock Springs, Dr. Pam McLaughlin checked Snoopy worriedly. The dog had been sneezing the day before. “Look here, old girl,” the vet lectured as she took her temperature, “you’ve kept your courage up until now. This is no time to get sick just when a lot of people are about to go to a lot of trouble to get you back to your family.”

Jim Storey, the animal control officer in Rock Springs, had volunteered to be Snoopy’s first driver. When he pulled up outside the clinic, Dr. McLaughlin bundled Snoopy in a sweater and carried her to the car. “She’s got a cold, Jim,” the vet said, “so keep her warm. Medicine and instructions and the special food for her kidney condition are in the shopping bag.”

“She’s got a long way to go,” Jim said. “Is she going to make it?”

“I wish I could be sure of it,” the doctor admitted. She put the little dog on the seat beside Jim and held out her hand. Snoopy placed her paw in it. “You’re welcome, old girl,” the vet said, squeezing it. “It’s been a pleasure taking care of you. The best of luck. Get home safely.”

Jim and Snoopy drove 108 miles to Rawlings, Wyoming. There they rendezvoused with Cathy English, who had come 118 miles from Casper to meet them. Cathy laughed when she saw Snoopy. “What a funny-looking, serious little creature you are to be traveling in such style,” she teased. “Imagine, private chauffeurs across five states.” But that evening, when she phoned Rod Hale to report that Snoopy had arrived safely in Casper, she called her “a dear old girl” and admitted that “If she were mine, I’d go to a lot of trouble to get her back, too.”

Snoopy went to bed at Cathy’s house—a nondescript little brown and white animal very long in the tooth—and woke the next morning a celebrity. Word of the seventeen-year-old dog with a bad cold who was being shuttled across mid-America to rejoin her family had gotten to the news media. After breakfast, dazed by the camera and lights but, as always, polite, Snoopy sat on a desk at the Casper Humane Society and obligingly cocked her head to show off the new leash that was a gift from Cathy. And that night, in Fort Wayne, the Topps were caught between laughter and tears as they saw their old girl peer out at them from the television set.

With the interview behind her, Snoopy set out for North Platte, 350 miles away, in the company of Myrtie Bain, a Humane Society official in Casper who had volunteered for the longest single hop on Snoopy’s journey. The two of them stopped overnight in Alliance, and Snoopy, taking a stroll before turning in, got a thorn in her paw. Having come to rely on the kindness of strangers, she held quite still while Myrtie removed it, and then continued to limp until Myrtie accused her of doing it just to get sympathy. Her sneezes, however, were genuine, and Myrtie put her to bed early, covering her with towels to keep off drafts.

In North Platte at noon the next day, more reporters and cameramen awaited them, but as soon as she’d been interviewed, Snoopy was back on the road for a 138-mile trip to Grand Island. Twice more that day she was passed along, arriving in Lincoln, Nebraska, after dark and so tired that she curled up in the first doggie bed she spotted despite the growls of its rightful owner.

In the morning her sneezing was worse and she refused to drink any water. Word of this was sent along with her, and as soon as she arrived in Omaha on the next leg, she was checked over by the Humane Society vet, who found her fever had dropped but she was dehydrated. A messenger was dispatched to the nearest store for Gatorade, to the fascination of reporters, who from then on headlined her as “Snoopy, the Gatorade Dog.”

With a gift of a new wicker sleeping basket and a note in the log being kept of her journey—“Happy to be part of the chain reuniting Snoopy with her family”—Nebraska passed the little dog on to Iowa. After a change of car and driver in Des Moines, Snoopy sped on and by nightfall was in Cedar Rapids. Pat Hubbard, in whose home she spent the night, was sufficiently concerned about her to set an alarm and get up three times in the night to force-feed her Gatorade. Snoopy seemed stronger in the morning, and the Puppy Express rolled on.

As happens to travelers, Snoopy’s outfit grew baggy and wrinkled, her sweater stretching so much that she tripped on it with almost every step. This did not go unnoticed, and by the time she reached Davenport, she was sporting a new sweater, as well as a collection of toys, food and water dishes and her own traveling bag to carry them in. The log, in addition to noting when she had been fed and walked, began to fill with comments in the margin: “Fantastic little dog!” “What a luv!” “Insists on sitting in the front seat, preferably in a lap.” “Likes the radio on.” “Hate to give her up! Great companion!”

At nightfall of her fifth and last full day on the road, Snoopy was in Chicago, her next-to-last stop. Whether it was that she was getting close to home or just because her cold had run its course, she was clearly feeling better. Indeed, the vet who examined her told the reporters, “For an old lady who’s been traveling all week and has come more than thirteen hundred miles, she’s in grand shape. She’s going to make it home tomorrow just fine.” The Topps, watching the nightly update of Snoopy’s journey on the Fort Wayne TV stations, broke into cheers.

The next day was Saturday, March 17. In honor of St. Patrick’s Day, the little dog sported a new green coat with a green derby pinned to the collar. The Chicago press did one last interview with her, and then Snoopy had nothing to do but nap until Skip Cochrane arrived from Fort Wayne to drive her the 160 miles home.

Hours before Snoopy and Skip were expected in Fort Wayne, the Topps were waiting excitedly at the Humane Society. Jodi and Matthew worked on a room-sized banner that read “Welcome Home, Snoopy! From Rock Springs, Wyoming, to Fort Wayne, Indiana, via the Puppy Express,” with her route outlined across the bottom and their signatures in the corner. Reporters from the Fort Wayne TV stations and newspapers, on hand to report the happy ending to Snoopy’s story, interviewed the Topps and the shelter’s staff, in particular Rod Hale, whose idea the Puppy Express had been. One interviewer asked him why the volunteers had done it. Why had thirteen staff members of ten Humane Societies and animal shelters gone to so much trouble for one little dog?

Rod told him what one volunteer had said to him on the phone. “It would have been so easy to tell Nancy Topp that nothing could be done. Instead, you gave all of us a chance to make a loving, caring gesture. Thank you for that.”

Somewhere amid the fuss and confusion, Rod found time to draw Nancy aside and give her word that Snoopy would be arriving home with her boarding bill marked “Paid.” An anonymous friend of the Humane Society in Casper had taken care of it.

“I thought I was through with crying,” Nancy said as the warm tears bathed her eyes. “Maybe it was worth our little dog and us going through all this just so we’d find out how kind people can be.”

The CB radio crackled and Skip Cochrane’s voice filled the crowded room. “Coming in! The Puppy Express is coming in!”

Nancy and Joe and the children rushed out in the subfreezing air, the reporters on their heels. Around the corner came the pickup truck, lights flashing, siren sounding. “Snoopy’s here!” shouted the children. “Snoopy’s home!”

And there the little dog was, sitting up on the front seat in her St. Patrick’s Day outfit, peering nearsightedly out of the window at all the commotion. After two months of separation from her family, after a week on the road, after traveling across five states for fifteen hundred miles in the company of strangers, Snoopy had reached the end of her odyssey.

Nancy got to the truck first. In the instant before she snatched the door open, Snoopy recognized her. Barking wildly, she scrambled into Nancy’s arms. Then Joe was there, and the children. Laughing, crying, they hugged Snoopy and each other. The family that didn’t give up on even its smallest member was back together again.

Sweet Elizabeth

Jane Bartlett first saw the white rabbit in a pet shop window at Easter time. The other rabbits were jostling for places at a bowl of chow, but this one was sitting up on her haunches, gazing solemnly back at the faces pressed against the glass staring at her. One ear stood up stiff and straight, as a proper rabbit’s ear should, but the other flopped forward over one eye, making her look as raffish as a little old lady who has taken a drop too much and knocked her hat askew.

An executive of the company in which Jane was a trainee came by, stopped to say hello and chuckled at the sight of the rabbit. Mr. Corwin was a friendly, fatherly man, and as they stood there smiling at the funny-looking creature, Jane found herself telling him stories about Dumb Bunny, the white rabbit she’d had as a small child who drank coffee from her father’s breakfast cup and once leaped after a crumb in the toaster, singeing his whiskers into tight little black corkscrews. Some of the homesickness Jane was feeling at being new in New York City must have been in her voice, for on Easter morning her doorbell rang and a deliveryman handed her a box.

She set it on the floor while she read the card, and Robert, her tomcat, always curious about packages, strolled over to sniff it. Suddenly he crouched, tail twitching, ready to spring. Jane cautiously raised the lid of the box and up popped the rabbit with the tipsy ear. The cat hissed fiercely. Peering nearsightedly at him, the rabbit shook her head, giving herself a resounding thwack in the nose with her floppy ear, hopped out of the box and made straight for the cat. He retreated. She pressed pleasantly forward. He turned and fled. She pursued. He jumped up on a table. She looked dazedly around, baffled by the disappearance of her newfound friend.

Jane picked her up to console her, and the rabbit began nuzzling her arm affectionately. “Don’t try to butter me up,” Jane told her sternly. “A city apartment is no place for a rabbit. You’re going straight back to the pet shop tomorrow.” The rabbit was a tiny creature, her bones fragile under her skin, her fur as white as a snowfield and soft as eiderdown. Gently Jane tugged the floppy ear upright, then let it slip like velvet through her fingers. How endearing the white rabbit was. Could she possibly … Jane shifted her arm and discovered a hole as big as a half-dollar chewed in the sleeve of her sweater. “That does it,” Jane said, hastily putting the rabbit down. “You’ve spoiled your chances.” With a mournful shake of her head, the rabbit hopped off in search of the cat.

Jane had a careful speech planned when she arrived at her office the next morning, but the kind executive looked so pleased with himself that the words went out of her head. “What have you named her?” he asked, beaming. She said the first thing that came to mind: “Elizabeth.”

“Sweet Elizabeth,” he said. “Wonderful!”

Sweet Elizabeth, indeed. Jane was tempted to tell him that Sweet Elizabeth had dined on her best sweater and spent the night in the bathroom, where she had pulled the towels off the racks and unraveled the toilet paper to make a nest for herself. Instead, she began to describe the rabbit’s crush on Robert the cat, and soon half the office had gathered around, listening and laughing. It was the first time anyone had paid the least bit of attention to her, and Jane began to wonder whether she wasn’t being too hasty about getting rid of Elizabeth. She did go to the pet shop on her lunch hour, however, just to sound them out. Their no-return policy was firm. The best they would do was sell Jane a wooden cage painted to look like a country cottage to keep the rabbit in.

“Don’t get the wrong idea,” she told Elizabeth that evening as she settled her into it. “It’s just temporary until I find a home for you.”

In the night it wasn’t the sound of the rabbit butting off the roof of the cottage that awakened Jane. She slept through that. It was the crash of the ficus tree going over when Sweet Elizabeth, having nibbled away the tasty lower leaves, went after the higher ones. The next day Jane bought a latch for the cottage. That night Elizabeth worked it loose and ate the begonias on the windowsill. The following day Jane bought a lock. That night Elizabeth gnawed a new front door in her cottage.

It was not hunger or boredom that fueled Elizabeth’s determination to get loose; it was her passion for Robert. The minute Jane let her out, she hopped to him and flung herself down between his paws. He, of course, boxed her soundly for her impertinence, but her adoration wore him down, and one day he pretended to be asleep when she lay down near enough to touch him with one tiny white paw. Soon, as though absentmindedly, he was including her in his washups, with particular attention paid to the floppy ear where it had dusted along the floor.

All of this made marvelous stories for Jane to tell in the office, and she discovered it wasn’t so hard to make friends after all. She even began to gain something of a reputation for wit when she described how Robert, finding that Elizabeth did not understand games involving catnip mice, invented a new one for the two of them.

Since Elizabeth followed him about as tenaciously as a pesky kid sister, he could easily lure her out onto Jane’s tiny terrace. Then he dashed back inside and hid behind a wastebasket. Slowly Elizabeth would hop to the doorway and peer cautiously about. Not seeing the cat anywhere, she’d jump down the single step, whereupon Robert would pounce, rolling them both over and over across the living room rug until Elizabeth kicked free with her strong hind legs. Punch-drunk from the tumbling about, she’d stagger to her feet, shake herself so that her tipsy ear whirled about her head, then scramble off and happily follow the cat outside again.

This game was not all that Elizabeth learned from Robert. He taught her something far more important, at least from Jane’s point of view. Out on the terrace were flower boxes that were much more to Robert’s liking than his indoor litter box. Time after time, while Robert scratched in the dirt, Elizabeth watched, her head cocked, her ear swinging gently. She was not a swift thinker, but one day light dawned. Robert stepped out of the flower box and she climbed in, which is how Elizabeth, with a little help from her friend, came to be housebroken.

With that problematic matter taken care of and all the plants eaten to nubbins anyway, Jane gave up trying to confine Elizabeth to her cottage and let her stay free. She met Jane at the door in the evening, just as Robert did, and sat up to have her head patted. She learned her name; she learned what “no” meant if said loudly and accompanied by a finger shaken under her nose; she learned what time meals were served and that food arrived at the apartment in paper bags. When Jane came home with groceries and set a bag even momentarily on the floor, Elizabeth’s strong teeth quickly ripped a hole in it. That is, unless she smelled carrots, in which case she tugged the bag onto its side and scrambled into it. If Jane got to the carrots before Elizabeth did and put them away on the bottom shelf of the refrigerator, the rabbit bided her time until Jane opened the door again, then she stood up on her hind legs and yanked the carrots back out. It got so that Jane never dared slam the refrigerator door without first making sure Elizabeth’s head was not inside it.

But then dinner would be over, the food put away, and Jane settled down to read in her easy chair. First Robert would come, big and purring and kneading with his paws to make a satisfactory spot for himself in her lap. Then Elizabeth would amble over, sit up on her haunches, her little paws folded primly on her chest, and study the situation to decide where there was room for her. With a flying leap, she’d land on top of Robert, throw herself over and push with her hind legs until she’d managed to wedge herself in between the cat and Jane. Soon the twitching of her nose would slow, then cease, and she would be asleep.

At such times, it was easy for Jane to let her hand stray over the soft fur, to call her Sweet Elizabeth, to forgive her all her many transgressions—the sock chewed into fragments, the gnawed handle on a pocketbook, the magazine torn into scraps. But one day Elizabeth went too far; she chewed the heels off Jane’s best pair of shoes. Jane decided she had to go. And she had a prospective family to adopt her: a young couple with three small children. She invited the parents, along with two other couples, to dinner.

All that rolling around on the rug with Robert had turned the white rabbit rather gray, and, wanting Elizabeth to look her most beguiling, Jane decided to give her a bath. She filled a dishpan with warm water and plopped Elizabeth into it. The rabbit sprang out. Jane hustled her back in and this time got a firm grip on her ears. Elizabeth kicked and Jane let go. On the third try, Jane got her thoroughly soaped on the back but Elizabeth’s powerful hind legs would not let her near her stomach. Persuading herself that no one would look at the rabbit’s underside, Jane rinsed her off as best she could and tried to dry her with a towel. Wet, the rabbit’s silky fur matted into intricate knots. Jane brushed; Elizabeth licked. Jane combed; Elizabeth licked. Hours later, Elizabeth’s fur was still sticking out in every direction and it was obvious that a soggy mass on her stomach was never going to dry. Afraid Elizabeth would get pneumonia, Jane decided to cut out the worst of the knots. With manicure scissors, she began carefully to snip. To her horror, a hole suddenly appeared. Elizabeth’s skin was as thin as tissue paper and the scissors had cut right through it. Jane rushed to get Mercurochrome and dab it on the spot. In the rabbit’s wet fur, the Mercurochrome spread like ink on blotting paper. Now Jane had a damp rabbit with a dirty-gray stomach dyed red.

The sight of her sitting up at the door to greet each new arrival sent Jane’s guests into gales of laughter, which Elizabeth seemed to enjoy. She hopped busily about to have her ears scratched. Jane was keeping a wary eye on her, of course, and saw the moment Elizabeth spotted the stuffed celery on the hors d’oeuvres tray. But Jane wasn’t quite quick enough. Elizabeth leaped and landed in the middle of the tray. Even that simply occasioned more laughter, and there were cries of protest when Jane banished Elizabeth to her cottage.

After dinner, Jane yielded and released her. Quite as though Elizabeth had used the time in her cottage to think up what she might do to entertain the party, she hopped into the exact center of the living room floor and gazed seriously around the circle of faces. When silence had fallen and she had everyone’s full attention, she leaped straight into the air, whirled like a dervish and crash-landed in a sprawl of legs and flying ears. The applause was prolonged. Peeping shyly from behind her ear, Elizabeth accepted it, looking quite pleased with herself.

The children’s father adored her, and when in the course of the evening he saw that Elizabeth went to the terrace door and scratched to be let out, he couldn’t wait to take her home. “She’s housebroken,” he reminded his wife, who was hesitating, “and the kids’ll love her.” Elizabeth, returning, climbed into his lap, and it was settled: Elizabeth was to go to her new family. Until the end of the evening. “What have you spilled on yourself?” the man’s wife asked. The edge of his suit jacket, from lapel to bottom button, was white. Elizabeth had nibbled it down to the backing.

“You rat,” Jane scolded her when the guests had gone. “I found a good home for you, and you blew it.” Elizabeth shook her head remorsefully, beating herself with her floppy ear, and wandered away. After Jane had cleaned up the kitchen and was ready for bed, she went looking for Elizabeth to put her in her cottage. She hunted high, low and in between. Where was she? Beginning to be frantic, she went through the apartment a second time. She even looked over the terrace railing, wondering for one wild moment if Elizabeth had been so contrite she’d thrown herself off. Only because there was nowhere else to search did Jane open the refrigerator door. There Elizabeth was, on the bottom shelf, having a late-night snack of carrot sticks and parsley.

For quite a while after that, nothing untoward happened, and Elizabeth, Robert and Jane settled into a peaceful and loving coexistence. When Jane watched Elizabeth sunbathing on the terrace beside Robert or sitting on her haunches to wash her face with her dainty paws or jumping into her lap to be petted, she found herself wondering how she could have imagined giving Elizabeth up. Until the day she did a thorough housecleaning and moved the couch. The rug had been grazed down to the backing.

“She’s eating me out of house and home. Literally,” Jane wailed to a college friend over lunch. “I’m going to have to turn her in to the ASPCA.”

“Don’t do that. I’ll take her,” Jane’s friend replied, surprising her because Jane knew she did not approve of pets in the house. “She can live in our garage. Evan’s ten now. It’ll be good for him to have the responsibility of caring for an animal.”

Jane’s bluff had been called. Could she really envision life without Sweet Elizabeth? She was silent. Her friend said, “Come on. We’ll go get her right now.”

Elizabeth met them at the door, sitting up as usual to have her ears scratched. “Oh, she’s cute,” said the friend, but so perfunctorily that Jane knew she had missed the point of Elizabeth. “Never mind,” Jane whispered into Elizabeth’s soft fur, “it’ll be all right. She’ll come to love you, just as I did, and you’ll be happy in the country.” Elizabeth shook her head slowly. Was there reproach in her eyes? Jane gave one last kiss to that foolish ear.

Robert was restless that evening, going often out on the terrace. “Oh, Robbie,” Jane told him, “I’m so sorry. She was your friend, too, and I didn’t think of that.” As Jane hugged him, the old emptiness returned, the emptiness of the time before Sweet Elizabeth when Jane used to imagine that everyone else’s phone was ringing, that everyone else had friends to be with and places to go. A little white rabbit who gave Jane the courage to reach out had made a surprising difference in her life.

It was weeks before she slammed the refrigerator door without a second thought, stopped expecting an innocent white face to come peeking around the terrace door, gave up listening for the thump of those heavy back feet. For a long time she didn’t trust herself even to inquire about Elizabeth. Then one day she was driving to Boston and, on impulse, decided to stop off in Connecticut to see her. No one was home, but the garage door was open. It was some time before Jane’s eyes got accustomed to the dark and she could distinguish the white blur that was Elizabeth. The little rabbit was huddled in a corner of her cottage, shaking with cold. The straw on the floor was soaking wet. The draft from the open door was bitter. Her food and water bowls were empty. Jane spoke her name and Elizabeth crept into her arms. Wrapping her in a sweater, Jane canceled her trip to Boston and headed back home.

She called her college friend the next day and told her she’d missed Elizabeth so much that she’d kidnapped her. That was all right, her friend said; what with the basketball season and all, her son hadn’t had much time for the rabbit. That left Jane with just one other phone call to make—the one canceling the order for a new rug. Then she settled back to watch Elizabeth and Robert rolling across the floor together.

Frankie Buck

On a narrow road twisting along beside a mountain stream lay a deer, struck and killed by a car.

A motorist happening along the infrequently traveled road swerved to avoid the deer’s body. As the driver swung out, he noticed a slight movement and stopped. There, huddled beside the dead doe, was a fawn, a baby who must have been born as its mother died, for the umbilical cord was still attached. “I don’t suppose you have a chance,” the motorist told the tiny creature as he tied off the cord, “but at least I can take you where it’s warm.”

The nearest place was the power plant of a state geriatric institution on a wooded mountaintop overlooking the town of Glen Gardner, New Jersey. Maintenance men there quickly gathered rags to make a bed for the fawn behind the boiler. When the fawn tried to suck the fingers reaching out to pet it, the men realized it was hungry and took a rubber glove, pricked pinholes in one finger, diluted some of the evaporated milk they used for their coffee and offered it to the fawn, who drank eagerly.

The talk soon turned to what to name the deer. Jean Gares, a small, spare man who was the electrician at the institution, had a suggestion. “If it’s a female, we can call her Jane Doe,” he proposed. “If it’s a male, Frank Buck.” The others laughed and agreed.

With the maintenance men taking turns feeding it around the clock, the little deer’s wobbly legs—and its curiosity—soon grew strong enough to bring it out from behind the boiler. The men on their coffee breaks petted and played with the creature, and as soon as they were certain that Frank Buck was the name that fit, they shortened it to Frankie and taught him to answer to it. The only one who didn’t call him Frankie, oddly enough, was Jean Gares. He, his voice rough with affection, addressed him as “you little dumb donkey,” as in “Come on and eat this oatmeal, you little dumb donkey. I cooked it specially for you.”

When Jean came to work at six each morning, always in his right-hand pocket was a special treat, an apple or a carrot, even sometimes a bit of chocolate, which Frankie quickly learned to nuzzle for. On nice days the two of them stepped outside, and Jean rested his hand on Frankie’s head and stroked his fur as they enjoyed the morning air together.

At the far end of the field in front of the power plant, deer often came out of the woods to graze in the meadow. When Frankie caught their scent, his head came up and his nose twitched. “We’d better tie him up or we’re going to lose him,” one of the men commented. Jean shook his head. “He’ll know when it’s time to go,” he said. “And when it is time, that’s the right thing for him to do.”

The first morning Frankie ventured away from the power plant, it wasn’t to join the deer in the meadow but to follow Jean. The two-story white stucco buildings at Glen Gardner were originally built at the turn of the century as a tuberculosis sanitarium and are scattered at various levels about the mountaintop. Cement walks and flights of steps connect them, and Jean was crossing on his rounds from one building to another one morning when he heard the tapping of small hooves behind him. “Go on home, you dumb donkey,” he told Frankie sternly. “You’ll fall and hurt yourself.” But Frankie quickly got the hang of the steps, and from then on the slight, white-haired man in a plaid flannel shirt followed by a delicate golden fawn was a familiar early morning sight.

One day, one of the residents, noticing Frankie waiting by the door of a building for Jean to reappear, opened the door and invited him in. Glen Gardner houses vulnerable old people who have been in state mental hospitals and need special care. When Frankie was discovered inside, the staff rushed to banish him. But then they saw how eagerly one resident after another reached out to touch him.

“They were contact-hungry,” says staff member Ruby Durant. “We were supplying marvelous care, but people need to touch and be touched as well.” When the deer came by, heads lifted, smiles spread and old people who seldom spoke asked the deer’s name. “The whole wing lit up,” remembers Ruby. “When we saw that and realized how gentle Frankie was, we welcomed him.”

His coming each day was something for the residents to look forward to. When they heard the quick tap-tap of Frankie’s hooves in the corridor, they reached for the crust, the bit of lettuce or the piece of apple they had saved from their own meals to give him. “He bowed to you when you gave him something,” says one of the residents. “That would be,” she qualifies solemnly, “if he was in the mood.” She goes on to describe how she offered Frankie a banana one day, and after she had peeled it for him, “I expected him to swallow the whole thing, but he started at the top and took little nibbles of it to the bottom, just like you or me.”

As accustomed as the staff became to Frankie’s presence, nevertheless, when a nurse ran for the elevator one day and found it already occupied by Frankie and a bent, very old lady whom she knew to have a severe heart condition, she was startled. “Pauline,” she said nervously, “aren’t you afraid Frankie will be frightened and jump around when the elevator moves?”

“He wants to go to the first floor,” Pauline said firmly.

“How do you know?”

“I know. Push the button.”

The nurse pushed the button. The elevator started down. Frankie turned and faced front. When the doors opened, he strolled out.

“See?” said Pauline triumphantly.

Discovering a line of employees in front of the bursar’s window one day, Frankie companionably joined the people waiting to be paid. When his turn at the window came, the clerk peered out at him. “Well, Frankie,” she said, “I wouldn’t mind giving you a paycheck. You’re our best social worker. But who’s going to take you to the bank to cash it?”

Frankie had the run of Glen Gardner until late fall, when superintendent Irene Salayi noticed that antlers were sprouting on his head. Fearful he might accidentally injure a resident, she decreed banishment. Frankie continued to frequent the grounds, but as the months passed he began exploring farther afield. An evening came when he did not return to the power plant. He was a year old and on his own.

Every morning, though, he was on hand to greet Jean and explore his pocket for the treat he knew would be there. In the afternoon he would reappear, and residents would join him on the broad front lawn and pet him while he munched a hard roll or an apple. A longtime resident named George, a solitary man with a speech defect who didn’t seem to care whether people understood what he said or not, taught Frankie to respond to his voice, and the two of them often went for walks together.

When Frankie was two years old—a sleek creature with six-point antlers and a shiny coat shading from tawny to deepest mahogany—there was an April snowstorm. About ten inches covered the ground when Jean Gares came to work on the Friday before Easter, but that didn’t seem enough to account for the fact that for the first time Frankie wasn’t waiting for him. Jean sought out George after he’d made his rounds and George led the way to a pair of Norway spruces where Frankie usually sheltered when the weather was bad. But Frankie wasn’t there or in any other of his usual haunts, nor did he answer to George’s whistle. Jean worried desperately about Frankie during the hunting season, as did everyone at Glen Gardner, but the hunting season was long over. What could have happened to him?

Jean tried to persuade himself that the deep snow had kept Frankie away, but he didn’t sleep well that night, and by Saturday afternoon he decided to go back to Glen Gardner and search for him. He got George, and the two of them set out through the woods. It was late in the day before they found the deer. Frankie was lying on a patch of ground where a steam pipe running underneath had thawed the snow. His right front leg was shattered. Jagged splinters of bone jutted through the skin. Dried blood was black around the wound. Jean dropped to his knees beside him. “Oh, you dumb donkey,” he whispered, “what happened? Were dogs chasing you? Did you step in a woodchuck hole?” Frankie’s eyes were dim with pain, but he knew Jean’s voice and tried to lick his hand.

Word that Frankie was hurt flicked like lightning through the center, and residents and staff waited anxiously while Jean made call after call in search of a veterinarian who would come to the mountain on a holiday weekend. Finally one agreed to come, but not until the next day, and by then Frankie was gone from the thawed spot. George tracked him through the snow, and when the vet arrived, he guided Jean and the grumbling young man to a thicket in the woods.

For the vet it was enough just to glimpse Frankie’s splintered leg. He reached in his bag for a hypodermic needle to put the deer out of his misery. “No,” said Jean, catching his arm. “No. We’ve got to try to save him.”

“There’s no way to set a break like that without an operation,” the vet said, “and this is a big animal, a wild animal. I don’t have the facilities for something like this.”

He knew of only one place that might. Exacting a promise from the vet to wait, Jean rushed to the main building to telephone. Soon he was back with an improvised sled; the Round Valley Veterinary Hospital fifteen miles away had agreed at least to examine Frankie if the deer was brought there. Cradling Frankie’s head in his lap, Jean spoke to him quietly until the tranquilizing injection the vet gave him took hold. When the deer drifted into unconsciousness, the three men lifted him onto the sled, hauled him out of the woods and loaded him into Jean’s pickup truck.

X-rays at the hospital showed a break so severe that a stainless-steel plate would be needed to repair it. “You’ll have to stand by while I operate,” Dr. Gregory Zolton told Jean. “I’ll need help to move him.” Jean’s stomach did a flip-flop, but he swallowed hard and nodded.

Jean forgot his fear that he might faint as he watched Dr. Zolton work through the three hours of the operation. “It was beautiful,” he remembers, his sweetly lined face lighting up. “So skillful the way he cleaned away the pieces of bone and ripped flesh and skin, then opened Frankie’s shoulder and took bone from there to make a bridge between the broken ends and screwed the steel plate in place. I couldn’t believe the care he took, but he said a leg that wasn’t strong enough to run and jump on wasn’t any use to a deer.”

After stitching up the incision, Dr. Zolton had orders for Jean. “I want you to stay with him until he’s completely out of the anesthetic to make sure he doesn’t hurt himself. Also, you’ve got to give him an antibiotic injection twice a day for the next seven days. I’ll show you how.”

There was an unused stable on the Glen Gardner grounds. Jean took Frankie there and settled him in a stall, and all night long Jean sat in the straw beside him. “Oh, you dumb donkey,” he murmured whenever Frankie stirred, “you got yourself in such a lot of trouble, but it’s going to be all right. Lie still. Lie still.” And he stroked Frankie’s head and held him in his arms when Frankie tried to struggle to his feet. With the soothing, known voice in his ear, Frankie each time fell back asleep, until finally, as the sun was coming up, he came fully awake. Jean gave him water and a little food, and only when he was sure Frankie was not frightened did he take his own stiff bones home to bed.

When word came that Frankie had survived the operation, a meeting of the residents’ council at Glen Gardner was called. Ordinarily it met to consider recommendations and complaints it wished to make to the staff, but on this day Mary, who was its elected president, had something different on her mind. “You know as well as I do that there’s no operation without a big bill. Now, Frankie’s our deer, right?” The residents all nodded. “So it stands to reason we’ve got to pay his bill, right?” The nods came more slowly.

“How are we going to do that?” Kenneth, who had been a businessman, asked.

After considerable discussion, it was decided to hold a sale of cookies that they would bake in the residents’ kitchen. Also, they would take up a collection, with people contributing what they could from their meager earnings in the sheltered workshop or the small general store the patients ran on the premises. “But first, before we do any of that,” a resident named Marguerite said firmly, “we have to send Frankie a get-well basket.”

The residents’ council worked the rest of the day finding a basket, decorating it and making a card. The next day a sack of apples was purchased at the general store and each apple was polished until it shone. Mary, Marguerite and George were deputized to deliver the basket. Putting it in a plastic garbage bag so the apples wouldn’t roll down the hill if they slipped in the snow, the three of them set out. They arrived without mishap and quietly let themselves into the stable. Frankie was sleeping in the straw, but he roused when they knelt beside him. Mary read him the card, Marguerite gave him an apple to eat, George settled the basket where he could see it but not nibble it and the three of them returned to the main building to report that Frankie was doing fine and was well pleased with his present.

By the seventh day after the operation, Jean called Dr. Zolton to say it was impossible to catch Frankie and hold him still for the antibiotic injections. Dr. Zolton chuckled. “If he’s that lively,” he told Jean, “he doesn’t need antibiotics.” But he warned it was imperative that Frankie be kept inside for eight weeks, for if he ran on the leg before it knit, it would shatter again.

Concerned about what to feed him for that length of time, Jean watched from the windows of his own house in the woods and on the grounds of Glen Gardner to see what the deer were eating. As soon as the deer moved away from a spot, Jean rushed to the place and gathered the clover, alfalfa, honeysuckle vines, young apple leaves—whatever it was the deer had been feeding on. Often George helped him, and each day they filled a twenty-five-pound sack. Frankie polished off whatever they brought, plus whatever residents coming to visit him at the stable had scavenged from their own meals in the way of rolls, carrots, potatoes and fruit.

“We’d go to see him, and oh, he wanted to get out so bad,” remembers Marguerite, a roly-poly woman with white hair springing out in an aura around her head. “Always he’d be standing with his nose pressed against a crack in the door. He smelled spring coming, and he just pulled in that fresh air like it was something wonderful to drink.”

When the collection, mostly in pennies and nickels, had grown to $135, the council instructed Jean to call Dr. Zolton and ask for his bill so they could determine if they had enough money to pay it. The day the bill arrived, Mary called a council meeting. The others were silent, eyes upon her, as she opened it. Her glance went immediately to the total at the bottom of the page. Her face fell. “Oh, dear,” she murmured bleakly, “we owe three hundred and ninety-two dollars.” Not until she shifted her bifocals did she see the handwritten notation: “Paid in Full—Gregory Zolton, DVM.”

When the eight weeks of Frankie’s confinement were up, Mary, Marguerite, George, Jean and Dr. Zolton gathered by the stable door. It was mid-June, and the grass was knee-deep in the meadow. Jean opened the barn door. Frankie had his nose against the crack as usual. He peered out from the interior darkness. “Come on, Frankie,” Jean said softly. “You can go now.” But Frankie was so used to someone slipping in and quickly closing the door that he didn’t move. “It’s all right,” Jean urged quietly. “You’re free.” Frankie took a tentative step and looked at Jean. Jean stroked his head. “Go on, Frankie,” he said, and gave him a little push.

Suddenly Frankie understood. He exploded into a run, flying over the field as fleetly as a greyhound, his hooves barely touching the ground.

“Slow down, slow down,” muttered Dr. Zolton worriedly.

“He’s so glad to be out,” Mary said wistfully. “I don’t think we’ll ever see him again.”

At the edge of the woods, Frankie swerved. He was coming back! Still as swift as a bird, he flew toward them. Near the stable he wheeled again. Six times he crossed the meadow. Then, flanks heaving, tongue lolling, he pulled up beside them. Frankie had tested his leg to its limits. It was perfect. “Good!” said George distinctly. Everyone cheered.

Soon Frankie was back in his accustomed routine of waiting for Jean by the power plant at six in the morning and searching his pockets for a treat, then accompanying him on at least part of his rounds. At noontime he canvassed the terraces when the weather was fine, for the staff often lunched outdoors. A nurse one day, leaning forward to make an impassioned point, turned back to her salad, only to see the last of it, liberally laced with Italian dressing, vanishing into Frankie’s mouth. Whenever a picnic was planned, provision had to be made for Frankie, for he was sure to turn up, and strollers in the woods were likely to hear a light, quick step behind them and find themselves joined for the rest of their walk by a companionable deer. One visitor whom nobody thought to warn became hysterical at what she took to be molestation by a large antlered creature until someone turned her pockets out and gave Frankie the after-dinner mints he had smelled there and of which he was particularly fond.

In the fall, Jean, anticipating the hunting season, put a red braided collar around Frankie’s neck. Within a day or two it was gone, scraped off against a tree in the woods. Jean put another on, and it, too, disappeared. “He doesn’t like red,” Pauline said. “He likes yellow.”

“How do you know?”

“I know.”

Jean tried yellow. Frankie kept the collar on. Jean was glad of this when Frankie stopped showing up in the mornings. He knew that it was rutting season and it was natural for Frankie to be off in the woods staking out his territory. The mountain was a nature preserve and no hunting was allowed, but still he worried about Frankie because poachers frequently sneaked into the woods; Frankie might wander off the mountain following a doe he fancied.

One day a staff member on her way to work spotted a group of hunters at the base of the mountain. Strolling down the road toward them was Frankie. She got out of her car, turned Frankie around so that he was headed up the mountain, then drove along behind him at five miles an hour. Frankie kept turning to look at her reproachfully, but she herded him with her car until she got him back to safety. On another memorable day, a pickup truck filled with hunters drove up to the power plant. When the tailgate was lowered, Frankie jumped from their midst. The hunters had read about Frankie in the local paper, and when they spotted a tame deer wearing a yellow collar, they figured it must be Frankie and brought him home.

After the rutting season, Frankie reappeared, but this time when he came out of the woods, three does were with him. And that has been true in the years since. The does wait for him at the edge of the lawn, and when he has visited with Jean and made his tour of the terraces and paused awhile under the crab apple tree waiting for George to shake down some fruit for him, Frankie rejoins the does and the little group goes back into the woods.

Because the hunting season is a time of anxiety for the whole of Glen Gardner until they know Frankie has made it through safely, George and the other people at Glen Gardner debate each fall whether to lock Frankie in the stable for his own safety. The vote always goes against it. The feeling is that Frankie symbolizes the philosophy of Glen Gardner, which is to provide care but not to undermine independence. “A deer and a person, they each have their dignity,” Jean says. “It’s okay to help them when they need help, but you mustn’t take their choices away from them.”

So, Frankie Buck, the wonderful deer of Glen Gardner, remains free. He runs risks, of course, but life itself is risky, and if Frankie should happen to get into trouble, he knows where there are friends he can count on.

I Love You, Pat Myers

Pat Myers was returning home after four days in the hospital for tests. “Hi, Casey. I’m back,” she called as she unlocked the door of her apartment. Casey, her African gray parrot, sprang to the side of his cage, chattering with excitement. “Hey, you’re really glad to see me, aren’t you?” Pat teased as Casey bounced along his perch. “Tell me about it.”

The parrot drew himself up like a small boy bursting to speak but at a loss for words. He jigged. He pranced. He peered at Pat with one sharp eye, then the other. Finally he hit upon a phrase that pleased him. “Shall we do the dishes?” he exploded happily.

“What a greeting.” Pat laughed, opening the cage so Casey could hop onto her hand and be carried to the living room. As she settled in an easy chair, Casey sidled up her arm; Pat crooked her elbow and the bird settled down with his head nestled on her shoulder. Affectionately Pat dusted the tips of her fingers over his velvety gray feathers and scarlet tail. “I love you,” she said. “Can you say ‘I love you, Pat Myers’?”

Casey cocked an eye at her. “I live on Mallard View.”

“I know where you live, funny bird. Tell me you love me.”

“Funny bird.”

A widow with two married children, Pat had lived alone for some years and devoted her energy to running a chain of dress shops. It was a happy and successful life. Then one evening she was watching television when, without warning, her eyes went out of focus. Innumerable tests later, a diagnosis of arteritis was established. Treatment of the inflammation of an artery in her temple lasted for more than a year and led to an awkward weight gain, swollen legs and such difficulty in breathing that Pat had to give up her business and for months was scarcely able to leave her apartment, which more and more grew to feel oppressively silent and empty. Always an outgoing, gregarious woman, Pat was reluctant to admit, even to her daughter, just how lonely she was, but finally she broke down and confessed, “Annie, I’m going nuts here by myself. What do you think—should I advertise for someone to live with me?”

“That’s such a lottery,” her daughter said. “How about a pet?”

“I’ve thought of that, but I haven’t the strength to walk a dog, I’m allergic to cats and fish don’t have a whole lot to say.”

“Birds do,” said her daughter. “Why not a parrot?”

That struck Pat as possibly a good idea, and she telephoned an ornithologist to ask his advice. After ruling out a macaw as being too big and a cockatoo or cockatiel as possibly triggering Pat’s allergies, he recommended an African gray, which he described as the most accomplished talker among parrots. Pat and Annie visited a breeder and were shown two little featherless creatures huddled together for warmth. The breeder explained that the eggs were hatched in an incubator and the babies kept separate from their parents so that they would become imprinted on humans and make excellent pets. “After your bird’s been with you for a while,” the breeder assured Pat, “he’ll think you’re his mother.”

“I’m not sure I want to be the mother of something that looks like a plucked chicken,” Pat said doubtfully. But Annie persuaded her to put a deposit down on the bird with the brightest eyes, and when he was three months old, feathered out and able to eat solid food, she went with Pat to fetch Casey home.

It was only a matter of days before Pat was saying to Annie, “I didn’t realize I talked so much. Casey’s picking up all kinds of words.”

“I could have told you,” her daughter said with a smile. “Just be sure you watch your language.”

“Who, me? I’m a perfect lady.”

The sentence Casey learned first was “Where’s my glasses?” and coming fast on its heels was “Where’s my purse?” Every time Pat began circling the apartment, scanning tabletops, opening drawers and feeling behind pillows, Casey set up a litany: “Where’s my glasses? Where’s my glasses?”

“You probably know where they are, smarty-pants.”

“Where’s my purse?”

“I’m looking for my glasses.”

“Smarty-pants.”

When Pat found her glasses and her purse and went to get her coat out of the closet, Casey switched to “So long. See you later.” And when she came home again, after going to the supermarket in the Minnesota weather, she called out, “Hi, Casey!” and Casey greeted her from the den with “Holy smokes, it’s cold out there!” She joked, “You took the words right out of my mouth.”

“What fun it is to have him,” Pat told Annie. “It makes the whole place feel better.”

“You know what?” Annie said. “You’re beginning to feel better, too.”

“So I am. They say laughter’s good for you, and Casey gives me four or five great laughs a day.”

Like the day a plumber came to repair a leak under the kitchen sink. In his cage in the den, Casey cracked seeds and occasionally eyed the plumber through the open door. Suddenly the parrot broke the silence by reciting, “One potato, two potato, three potato, four …”

“What?” demanded the plumber from under the sink.

Casey mimicked Pat’s inflections perfectly. “Don’t poo on the rug,” he ordered.

The plumber pushed himself out from under the sink and marched into the living room. “If you’re going to play games, lady, you can just get yourself another plumber.” Pat looked at him blankly. The plumber hesitated. “That was you saying those things, wasn’t it?”

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/jo-coudert/the-dog-who-healed-a-family/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Jo Coudert

In this charming collection of nineteen stories, you can't help but fall in love with the unlucky fawn who is saved by a nursing home, the troublesome rabbit who warms her way into a new family and the good (German) shepherd who comforts the sick.These are stories of hope, humor, triumph, loyalty, compassion, life and even death—but most of all, these are stories of love and the extraordinary animals who make our lives the richer for it.

the

dog who

healed

a family

And Other True Animal

Stories That Warm the

Heart & Touch the Soul

Jo Coudert

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

Preface

All the stories in this book are about animals, and all are true. What the stories have in common is the love and caring that can exist between animals and people. Nancy Topp struggled for weeks to get a seventeen-year-old dog home across fifteen hundred miles. Gene Fleming fashioned shoes for a goose born without feet and supported the goose in a harness until he learned to walk. Months after their javelina disappeared, Patsy and Buddy Thorne were still roaming ranch lands in Texas, Bubba’s favorite chocolate in their pockets, searching for their wild pig.

The Thornes recently sent a clipping from their local newspaper describing how a group of men out hunting with bows and arrows came upon a javelina. The animal stood still, gazing at the men, while they shot at it three times. When all three arrows failed to strike home, one of the men ventured close enough to pet the animal and found it was tame and welcomed the attention.

What is amazing about the report is not that the animal was Bubba—it was not—but that the hunters shot three times at a creature that was not big enough or wild enough to be a threat to them and that did not provide sport by running. And because the meat of a javelina is too strong-tasting to be palatable, they were not interested in it for food.

The hunters shot at the javelina because it was there, which is the same reason a neighbor who lives downriver from me catches all the trout within hours of the time the state fish and wildlife service stocks the stream. An amiable man who loves his grandchildren, the neighbor has built the children a tree platform where they can sit silently and shoot at the deer who come to the river to drink at twilight. He also sets muskrat traps in the river and runs over woodchucks and possums on the road.

The family doesn’t eat the deer; the frozen body of a doe has been lying all winter in the field in back of my woods. Nor does anyone eat the trout the man catches; he tosses them into a little pond on his property where they stay until they become too numerous and die from lack of oxygen. When I once asked this ordinary, pleasant fellow why he’d gone out of his way to run over a raccoon crossing the road, he looked at me in surprise. “It’s an animal!” he said as though that quite explained it.

To many people it is sufficient explanation. After all, did not Jehovah tell Noah and his sons that all the beasts of the earth and fish of the sea were delivered into the hands of man? Surely this is a license to destroy them even if we have no better reason at the time than the fact that they exist and we wish to.

Or is it? Belatedly we are beginning to realize that the duality of people and animals, us and them, is false, just as we have discovered that there is no split between us and the world. The world is us and we are the world. We cannot simply exploit and destroy, either the world or the animals in it, if we are not at the same time to do ourselves irreparable harm.

Consider what a Native American, Chief Seattle, said in 1854: “What is man without the beasts? If all the beasts were gone, man would die from a great loneliness of spirit. For whatever happens to the beasts, soon happens to man. All things are connected. This we know: The Earth does not belong to man; man belongs to the Earth. This we know: All things are connected like the blood which unites one family. All things are connected. Whatever befalls the Earth befalls the sons of the Earth. Man did not weave the web of life. He is merely a strand in it. Whatever he does to the web, he does to himself.”

The world belongs to the animals just as much as to us. Let us be unselfish enough to share it with them openly and generously. Which is to say, when you come upon a lost dog or an orphaned fawn or a goose born without feet, give it nothing to fear from you, grant it safety, offer to help if you can, be kind. In return, as the stories here show, you will sometimes find a welcome companionship, and surprisingly often love.

Jo Coudert

Califon, New Jersey

The Puppy Express

Curled nose to tail, the little dog was drowsing in Nancy Topp’s lap as the truck rolled along the interstate. Suddenly Nancy felt her stiffen into alertness. “What’s the matter, old girl?” Nancy asked. At seventeen, Snoopy had a bit of a heart condition and some kidney problems, and the family was concerned about her.

Struggling to her feet, the dog stared straight ahead. She was a small dog, with a dachshund body but a beagle head, and she almost seemed to be pointing. Nancy followed the dog’s intent gaze, and then she saw it, too. A wisp of smoke was curling out of a crack in the dashboard. “Joe!” she shouted at her husband at the wheel. “Joe, the engine’s on fire!”

Within seconds the cab of the ancient truck was seething with smoke. Nancy and Joe and their two children—Jodi, twelve, and Matthew, fifteen—leaped to the shoulder of the road and ran. When they were well clear, they turned and waited for the explosion that would blow everything they owned sky-high. Instead, the engine coughed its way into silence, gave a last convulsive shudder and died.

Joe was the first to speak. “Snoopy,” he said to the little brown and white dog, “you may not hear or see so good, but there’s nothing wrong with your nose.”

“Now if you could just tell us how we’re going to get home,” Matthew joked. Except it wasn’t much of a joke. Here they were, fifteen hundred miles from home, stranded on a highway in Wyoming, with the truck clearly beyond even Joe’s gift for repairs. The little dog, peering with cataract-dimmed eyes around the circle of faces, seemed to reflect their anxiety.

The Topps were on the road because five months earlier a nephew had told Joe there was work to be had in the Napa Valley and Joe and Nancy decided to take a gamble on moving out there. Breaking up their home in Fort Wayne, Indiana, they packed up the kids and Snoopy and set out for California. But once there, the warehousing job Joe hoped for did not materialize, Nancy and the kids were sharply homesick and their funds melted away. Now it was January and, the gamble lost, they were on their way back home to Fort Wayne.

The truck had gotten them as far as Rock Springs, Wyoming, but now there was nothing to do but sell it to a junk dealer for $25 and hitch a ride to the bus station. Two pieces of bad news greeted them there. Four tickets to Fort Wayne came to more money than they had, much more, and dogs were not allowed on the bus.

“But we’ve got to take Snoopy with us,” Nancy pleaded with the ticket seller, tears welling in her eyes. It had been a disastrous day, but this was the worst news of all.

Joe drew her away from the window. It was no use getting upset about Snoopy, he told her, until they figured out how to get themselves on the bus. With no choice but to ask for help, they called Travelers Aid, and with kind efficiency the local representative arranged for a motel room for them for the night. There, with their boxes and bags piled in a corner, they put in a call to relatives back home, who promised to get together money for the fare and wire it the next day.

“But what about Snoopy?” Matthew said as soon as his father hung up the phone.

“We can’t go without Snoopy,” Jodi stated flatly.

Joe picked up the little dog. “Snoopy,” he said, tugging her floppy ears in the way she liked, “I think you’re going to have to hitchhike.”

“Don’t tease, Joe,” Nancy said curtly.

“I’m not teasing, honey,” he assured her, and tucked Snoopy into the crook of his arm. “I’m going to try to find an eastbound truck to take the old girl back for us.”

At the local truck stop, Joe sat Snoopy on a stool beside him while he fell into conversation with drivers who stopped to pet her. “Gee, I’d like to help you out,” one after another said. “She’s awful cute and I wouldn’t mind the company, but I’m not going through Fort Wayne this trip.” The only driver who might have taken her picked Snoopy up and looked at her closely. “Naw,” the man growled, “with an old dog like her, there’d be too many pit stops. I got to make time.” Still hopeful, Joe tacked up a sign asking for a ride for Snoopy and giving the motel’s phone number.

“Somebody’ll call before bus time tomorrow,” he predicted to the kids when he and Snoopy got back to the motel.

“But suppose nobody does?” Jodi said.

“Sweetie, we’ve got to be on that bus. The Travelers Aid can only pay for us to stay here one night.”

The next day Joe went off to collect the wired funds while Nancy and the kids sorted through their possessions, trying to decide what could be crammed into the six pieces of luggage they were allowed on the bus and what had to be left behind. Ordinarily Snoopy would have napped while they worked, but now her eyes followed every move Nancy and the children made. If one of them paused to think, even for a minute, Snoopy nosed at the idle hand, asking to be touched, to be held.

“She knows,” Jodi said, cradling her. “She knows something awful is going to happen.”

The Travelers Aid representative arrived to take the belongings they could not pack, for donation to the local thrift shop. A nice man, he was caught between being sympathetic and being practical when he looked at Snoopy. “Seventeen is really old for a dog,” he said gently. “Maybe you just have to figure she’s had a long life and a good one.” When nobody spoke, he took a deep breath. “If you want, you can leave her with me and I’ll have her put to sleep after you’ve gone.”

The children looked at Nancy but said nothing; they understood there wasn’t any choice, and they didn’t want to make it harder on their mother by protesting. Nancy bowed her head. She thought of all the walks, all the romps, all the picnics, all the times she’d gone in to kiss the children good-night and Snoopy had lifted her head to be kissed, too.

“Thank you,” she told the man. “It’s kind of you to offer. But no. No,” she repeated firmly. “Snoopy’s part of the family, and families don’t give up on each other.” She reached for the telephone book, looked up kennels in the yellow pages and began dialing. Scrupulously she started each call with the explanation that the family was down on their luck. “But,” she begged, “if you’ll just keep our little dog until we can find a way to get her to Fort Wayne, I give you my word we’ll pay. Please trust me. Please.”

A veterinarian with boarding facilities agreed finally to take her, and the Travelers Aid representative drove them to her office. Nancy was the last to say goodbye. She knelt to take Snoopy’s frosted muzzle in her hands. “You know we’d never leave you if we could help it,” she whispered, “so don’t give up. Don’t you dare give up. We’ll get you back somehow, I promise.”

Once back in Fort Wayne, the Topps found a mobile home to rent, one of Joe’s brothers gave them his old car, sisters-in-law provided pots and pans and bed linens, the children returned to their old schools and Nancy and Joe found jobs. Bit by bit the family got itself together. But the circle had a painful gap in it. Snoopy was missing. Every day Nancy telephoned a different moving company, a different trucking company, begging for a ride for Snoopy. Every day Jodi and Matthew came through the door asking if she’d had any luck and she had to say no.

By March they’d been back in Fort Wayne six weeks and Nancy was in despair. She dreaded hearing from Wyoming that Snoopy had died out there, never knowing how hard they’d tried to get her back. One day a friend suggested she call the Humane Society. “What good would that do?” Nancy said. “Aren’t they only concerned about abandoned animals?” But she had tried everything else, so she telephoned Rod Hale, the director of the Fort Wayne Department of Animal Control, and told him the story.

“I don’t know what I can do to help,” Rod Hale said when she finished. “But I’ll tell you this. I’m sure going to try.” A week later, he had exhausted the obvious approaches. Snoopy was too frail to be shipped in the unheated baggage compartment of a plane. A professional animal transporting company wanted $655 to bring her east. Shipping companies refused to be responsible for her. Rod hung up from his latest call and shook his head. “I wish the old-time Pony Express was still in existence,” he remarked to his assistant, Skip Cochrane. “They’d have passed the dog along from one driver to another and delivered her back home.”

“It’d have been a Puppy Express,” Skip joked.

Rod thought for a minute. “By golly, that may be the answer.” He got out a map and a list of animal shelters in Wyoming, Nebraska, Iowa, Illinois and Indiana, and picked up the phone. Could he enlist enough volunteers to put together a Puppy Express to transport Snoopy by stages across five states? Would people believe it mattered enough for a seventeen-year-old dog to be reunited with her family that they’d drive a hundred or so miles west to pick her up and another hundred or so miles east to deliver her to the next driver?

In a week he had his answer, and on Sunday, March 11, he called the Topps. “How are you?” he asked Nancy.

“I’d feel a lot better if you had some news for me.”

“Then you can begin feeling better right now,” Rod told her jubilantly. “The Puppy Express starts tomorrow. Snoopy’s coming home!”

Monday morning, in Rock Springs, Dr. Pam McLaughlin checked Snoopy worriedly. The dog had been sneezing the day before. “Look here, old girl,” the vet lectured as she took her temperature, “you’ve kept your courage up until now. This is no time to get sick just when a lot of people are about to go to a lot of trouble to get you back to your family.”

Jim Storey, the animal control officer in Rock Springs, had volunteered to be Snoopy’s first driver. When he pulled up outside the clinic, Dr. McLaughlin bundled Snoopy in a sweater and carried her to the car. “She’s got a cold, Jim,” the vet said, “so keep her warm. Medicine and instructions and the special food for her kidney condition are in the shopping bag.”

“She’s got a long way to go,” Jim said. “Is she going to make it?”