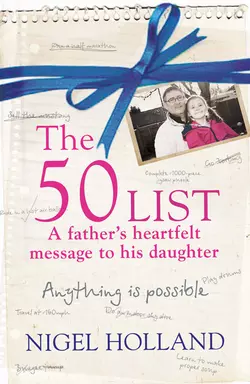

The 50 List – A Father’s Heartfelt Message to his Daughter: Anything Is Possible

Nigel Holland

Nigel has a disability – an inherited disease that means his nerves don’t tell his muscles what to do – but he does not consider himself disabled. His youngest daughter Ellie has been diagnosed with the same condition. To inspire Ellie, and show her anything is possible, Nigel set himself a list of fifty challenges. This is the story of that list.Nigel and his wife Lisa have three children and, like all parents, they have always wanted the best for their kids. For Nigel, this meant helping them to understand that life is to be challenged: to be explored and enjoyed, no matter what obstacles you might have to face.Even during the darkest times, Nigel has never let anything stop him from realising his dreams. To inspire his youngest daughter, and let her see firsthand that anything is possible, Nigel set himself a list of 50 challenges to complete before he turned 50. Some are crazy, wild physical challenges, others are seemingly simple tasks people often take for granted. Some are activities Nigel has done before, others are skills he has learnt to cope with his condition that he wants to share with other people. All of them hold huge emotional significance to Nigel and his family.This is the heart-warming account of the year Nigel completed The 50 List. Inspiring and surprising, it will move you to tears and laughter, and leave you believing that you really can accomplish anything.

(#ub2757e0e-e927-5461-a178-28c8a816e26e)

(#ub2757e0e-e927-5461-a178-28c8a816e26e)

For my darling wife, Lisa, and my wonderful children, Mattie, Amy and Ellie: with you beside me, I know anything is possible

Thanks also to my brothers, Mark and Gary, and my sister, Nicola: your love and support means everything to me

Finally, dear Mum and Dad: thanks for everything

(#ub2757e0e-e927-5461-a178-28c8a816e26e)

‘All men dream, but not equally. Those who dream by night in the dusty recesses of their minds, wake in the day to find that it was vanity: but the dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act on their dreams with open eyes, to make them possible.’

T. E. LAWRENCE

CONTENTS

Cover (#u05ee0456-54ec-521a-86a0-dca2d19f1d2e)

Title Page (#ulink_8c60ed08-c335-5378-8ec6-29689657bdd9)

Dedication (#ulink_0558adaa-ae2c-51e7-9a37-5bd125fb0a06)

Epigraph (#ulink_60d56ea4-ebfc-57db-9618-7c8fa417b9f5)

Introduction (#ulink_144168cd-61f7-5654-afe7-ed01eeac1211)

SEPTEMBER (#ulink_a91a8bb7-7943-5727-bcd9-44393eb0030d)

NOVEMBER (#ulink_929f1a0f-70a0-5f3f-816f-86f77b692457)

DECEMBER (#ulink_68594121-ca52-55c4-9449-93506610804e)

FEBRUARY (#ulink_e9acade2-d14e-545d-8bd2-c8886ddf6f4c)

MARCH (#litres_trial_promo)

APRIL (#litres_trial_promo)

MAY (#litres_trial_promo)

JUNE (#litres_trial_promo)

JULY (#litres_trial_promo)

AUGUST (#litres_trial_promo)

SEPTEMBER (#litres_trial_promo)

OCTOBER (#litres_trial_promo)

NOVEMBER (#litres_trial_promo)

DECEMBER (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

The 50 List (#litres_trial_promo)

My Comedy Sketch (#litres_trial_promo)

Picture Section (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#ub2757e0e-e927-5461-a178-28c8a816e26e)

Just like any parent, I want the best for my children. I want them to feel safe, to be confident and to grow up with the understanding that life is to be challenged: to be explored and enjoyed, no matter what obstacles you might have to face. My wife and I have three great children and I am very proud of them. The two eldest, Matthew (15) and Amy (13), have grown up with responsibilities that most of their peers have never experienced. I am in a wheelchair, and being a wheelchair-using dad limits me from doing some of the things that other dads do, like football and cycling – activities that other parents take for granted. But their understanding of the issues I face makes the relationship I have with my children what it is: close, loving and, most of all, fun. They are growing up to be caring and thoughtful individuals with an empathy that belies their ages.

Ten years ago my wife, Lisa, gave birth to our youngest daughter, Eleanor. She has been diagnosed with the same condition that I have: Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT) or peroneal muscular atrophy, also known as hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy. What this means in practical terms is that there is wastage of the muscles in the lower part of the limbs. I can no longer walk and my hand strength is very weak, limiting my dexterity. Ellie is walking still but her gait – the way she walks – is affected. In 2010 she had to undergo surgery on her legs to try to straighten her ankles, as her tendons were pulling her feet inwards. The disability can affect people in many different ways.

Both my wife and I want to see Ellie enjoy life just as much as her older siblings and we are aware that she will face problems as she grows up, but what we want her to understand is that those problems can be overcome. In my life I have done many crazy and wonderful things that many people thought were beyond my capabilities: water-skiing, off-road 4x4, go-karting, gliding, diving – the list goes on. I even played drums in a band in the 1980s, reaching the dizzy heights of playing the Hippodrome at Leicester Square. Up until 2010 I was competing in the National Drag Racing Championships in a powerful Ford Mustang race car. I’ve never let anything stop me from realizing my dreams, so I want Ellie to know that her capabilities are to be explored. And it’s not just that there’s nothing wrong with ‘having a go’, either. It’s that you’ll never know what you can do till you try.

Then, one day, not so long ago, something else struck me: that there’s a saying – or, more correctly, an idiom – that we all know, which goes ‘actions speak louder than words’. And as soon as it occurred to me, that was it; I was away. I wouldn’t just tell her. I would show her.

Nigel Holland, December 2012

SEPTEMBER (#ub2757e0e-e927-5461-a178-28c8a816e26e)

‘Dad,’ Ellie says to me, ‘you’re mad.’

‘Well, you knew that already,’ I say, grinning at the look of incomprehension on her face as she works her way down the piece of paper in her hand. It is a list. A list of all the crazy things I plan to do over the coming months. I can tell they’re crazy just by looking at the expression on her face.

‘Yeah, I know, Dad,’ she says, ‘but this is a big list. How are you going to do everything on it in one year?’

‘I’m going to be doing even more than that,’ I correct her. ‘Because it’s not finished yet. I was hoping you could suggest some things to put on it too.’

She looks again, her slender index finger tracing a line down the page. It’s actually two lists, one marked ‘extreme’ and one marked ‘other’. Ellie points to an item marked ‘extreme’.

‘What’s this?’ she asks.

‘Zorbing?’ I say, reading it. ‘Oh, it’s great fun. It’s rolling down a hill inside a very large bouncy ball.’

She takes this in, and her look of incomprehension doesn’t change. Though I’ve tried to explain to Ellie the main reason why I’m doing this – to inspire her – Ellie has a learning difficulty, which means she doesn’t always get the bigger picture. But perhaps she doesn’t need to. Not now, at least. All I really want is that she gets caught up in the excitement and thinks ‘can’ rather than ‘can’t’. That’ll be good enough for me. Though, hmm, ‘zorbing’ – she’s probably right: I am mad.

It’s late in the afternoon, the watery late-September sun is almost gone now, and we’re contemplating what seemed like a brilliant idea when I first thought of it, but which now seems to mark me out as bonkers: a list of 50 challenges, of all kinds, to be completed within the year, to prove that a) you really can do almost anything that you put your mind to and b) turning 50 doesn’t spell the end of any sort of life other than the pipe-and-slippers kind.

Because that’s what had struck me a couple of weeks earlier when a work colleague had mentioned my upcoming 50th birthday, saying that 50 – the big 50 – was a particularly depressing milestone. One that marked the end of youth and the beginning of ‘being old’, which was something I was not prepared to be. ‘And your point?’ I’d retorted, rising swiftly to the bait. ‘I don’t mind getting old, but I refuse to grow up.’ It was a thought – and a mindset – that had stayed with me all day.

And here we were, the idea having not only taken root but also sprouted. And what had started as a whimsical, unfocused kind of wish list had somehow become a full-blown plan. A plan to prove something to both myself and my children – particularly my youngest, ‘disabled’ daughter.

‘OK,’ I say to Ellie. ‘You think of some challenges.’

She considers it for a few seconds, chewing thoughtfully on her lower lip. ‘Erm, maybe jump over a tall building?’ she offers finally. And I’m pretty sure she’s only half joking.

Which is nice – it’s always good to be your children’s superhero – but her idea is not do-able. Even for me. I say so.

‘What about flying, then?’ she says.

‘What, you mean as in a plane?’

‘No,’ she retorts, in all seriousness. ‘Like Superman!’

Silly me. I should have known. Of course she means like Superman. I am her hero, just the same way my dad was my hero. It’s almost 30 years now since I lost him – over half a lifetime. And I still can’t believe he’s never coming back.

‘Ah,’ I tell Ellie, ‘there’s a problem with that one. I don’t have any red underpants that will fit over my trousers.’

She knows she’s being teased and pulls her ‘Dad, I’m being teased’ face. ‘Well,’ I say, ‘you started it. What do you expect? But I can sort of fly,’ I say, pointing to another item I’ve already added. ‘Indoor skydiving. That’s pretty much like flying.’

‘What, you can fly?’ She looks impressed now. ‘What, with no strings or anything?’

‘With no strings or anything. The air holds you up.’ I try to explain how it works, but I’m not sure she quite gets it. ‘Come on,’ I say. ‘What else? Think – what would you like to do, if you could do a challenge yourself?’

‘Fly a kite,’ she says, decisively. ‘I’d like to fly a kite – a big pink one. Hey, but Dad?’

‘What?’

‘I’ve got a brilliant one for you. Dye your hair pink!’

She is bright eyed with excitement at this unexpected brainwave. Perhaps a little too bright eyed for my liking.

‘Okaaayyy,’ I say slowly. ‘That can go under “maybe”.’

Ellie shakes her head. ‘You can’t do maybes. You have to definitely promise.’

I try to regroup. How on earth am I going to get out of this one? The plan is to do all this stuff to inspire others, her included; not to look like a complete idiot, for a bet.

‘I can’t promise definitely,’ I say. ‘I might not have time to fit them all in, might I?’

‘But if you do …’

‘Then how about I put it on my “reserve list”?’ I suggest. I have my clients to think about, after all. I write ‘reserve list’ on the bottom, followed by ‘Dye hair pink’. Which her expression seems to suggest might have mollified her. ‘Anything else?’ I ask, trying to redirect her thoughts a bit. Which is probably tempting fate, but never mind.

‘What about a puzzle?’ she suggests.

‘A jigsaw puzzle?’

‘Yes. A jigsaw puzzle.’

‘You know what, Ellie?’ I say, already picking up my pencil. ‘That is an excellent idea. Assuming you’ll help me, of course.’ I wiggle my fingers, which are probably cursing me already for the torture I am about to inflict on them.

‘Course I’ll help you,’ she says. ‘I’m brilliant at puzzles.’

‘OK,’ I say, adding it. ‘How many pieces should we go for?’

‘Five thousand,’ she says, without a flicker of hesitation. ‘That won’t be too hard for your fingers, will it, Dad?’

‘Piece of cake,’ I tell my daughter. And at that point I believe it.

Mad. Just as Ellie has already said.

NOVEMBER (#ub2757e0e-e927-5461-a178-28c8a816e26e)

11 November 2011

Number of challenges still to be completed: 50.

Number of times I have wondered what I’ve let myself in for: Already too numerous to count.

Now I’m up and running with this thing, there’s no backing out. No, I know I’m not exactly running yet – my plan is so far little more than a sketched-out idea – but having come up with it, I realize that committing to all these challenges is beginning to feel more and more like a challenge in itself. It’s one thing telling yourself you’re going to be able to achieve all of them, but quite another when you tell everyone else you are as well. Another still when the person you most want to do it for is one of the people dearest to you in the world.

As it turns out, I have been somewhat beaten off the blocks anyway, in terms of challenges, because only two weeks after formulating the plan, and my subsequent optimistic conversation with Ellie, I had another one lobbed into my lap. And it was a big one. A particularly big one for a man of my age. After 13 happy years working as a web developer, I was made redundant from my job.

Sitting in the room that was once my study but has now been re-christened my ‘office’, in recognition of this new and exciting life stage, I think of Tommy Cooper and I smile. ‘Just like that’ – wasn’t that his tag line? I was made redundant, just like that. At least that’s the way it feels to me, though perhaps I should have seen it coming. Yet at the same time, I can’t stop thinking about the timing of everything. Perhaps fate’s played a part in all this happening when it has, because now nothing stands in the way of my doing what I’ve set out to do. I am all out of excuses. I have time on my hands. I also have a new item to add to my list of challenges: ‘Make my business work.’ Which is handy, because the zero gravity flight that it has now taken the place of was way too expensive to even begin to contemplate, and even more so for a guy with a family and a mortgage, but – crucially, and suddenly – without a job.

But it was definitely a job I’m going to miss. Though in recent years, after my firm was taken over by an American company, morale was low, stress was high and business was a bit shaky, the timing of the redundancy, in one sense, couldn’t have been worse. During the last few months I was working for a really great manager, and though mostly from home – which was isolating, as I felt cut off from the office gossip – I felt energized about work in a way I hadn’t in a long time, and I’m sad that it’s all come to an end.

There was also the big question to face: how on earth would I pay the mortgage? But, though the simple option would be to take my skills and go and find another job with them, I had, and still have, a nagging sense that I should be taking the plunge and going it alone. Now or never. And I’m definitely less keen on never.

Which leaves me with now – do or die. Which is exciting yet scary.

So sending off my entry form for the Silverstone half marathon seems a little less daunting as a consequence. Though on the one hand it feels like one of the most difficult of all the challenges – 13 miles, and in a wheelchair: I am going to need to train and then some – when I compare it to the career cliff face I’ve just been forced to jump from (hoping to fly, obviously, rather than fall flat on my face) it feels suddenly more in the realms of the ‘actually achievable’: a solid thing, something I have control over.

As I sit at my desk filling in the online application form, I get a picture in my head of my beloved parents. Sadly, I don’t have many pictures of them together. I have old, individual ones, taken with primitive cameras, black, white and sepia, and fluffy-edged with age. But nothing recent. Not many that show how much they loved one another. If I could change one thing in my life it would be that they could be here to see me do this. You never lose that feeling, I think, whatever your age.

* * *

According to family folklore, which is generally the most dubious kind, I always liked making an entrance. There must be some truth in it, though, because the story goes that when I first looked like arriving, on 8 December 1962, my mother was busy serving dinner to no fewer than 12 guests.

To my perhaps unimaginative male eye, this seems quite a daring thing to be doing at any time, but particularly when you are 40 weeks pregnant. What became of the dinner guests and their dinners I don’t know. All I do know is that I appeared several hours later, making landfall at Shrub Hill Hospital in Worcester, which was where my father had hastily relocated us. It’s also said – more family folklore, this time probably 100 per cent reliable – that I was encouraged on my way by the irresistible smell of roast beef.

I was the third of three boys (which perhaps explains my mother’s cool head in the face of a dozen hungry dinner guests), my brothers Mark and Gary then being six and four respectively. But I didn’t keep my privileged position for very long. No sooner had I turned two than my world was disrupted – by the arrival of my baby sister, Nicola.

Nikki’s arrival caused disruption in other ways as well. Unplanned, she came under the banner of ‘unexpected gifts from heaven’, but for me and my brothers she was anything but. We had wanted a dog. We had been promised a dog. Well, if not exactly promised, certainly given to believe that having a dog was not entirely out of the question. So for the duration of the pregnancy, we were miffed (though in my case, possibly still hopeful she might turn out to be a dog) and according to my mother, we spent the first six months of her life demanding that she be called Rover.

‘Just as well you were a girl,’ I recall my mother telling her later, ‘or that might actually have turned out to be your name.’

The house the family lived in when I was born was in Britannia Square in Worcester. I have only a few memories of my time there. The house stood very tall, with three storeys, and was painted bright white. In my mind’s eye, it was very grand looking, our family residence, though as a small child I naturally had a small child’s perspective, so perhaps it wasn’t quite as grand as it seemed.

Either way, it was home, and it was a happy home as well. Though my memories of it are no more than snapshots, I recall a wind-up mouse, which I wound and launched accidentally into my potty – the potty into which I’d just peed. I also have a clear early memory of my dad stepping out onto the roof of the house to sort out some tiling that had come loose. He was a jack of all trades, Dad – a builder, decorator and, at that time, a bus driver, and I can still recall how incredible it felt to look up and see him, high above my head, fixing the roof.

But then everything my dad did seemed incredible to me. I remember walking down the road with my mum, brothers and baby sister, and how we watched as a double-decker bus drove past us into the depot. Minutes later we had followed it – Mum had to deliver Dad’s packed lunch to him – and I recall how thrilling it was to see my father climbing down from the cab of that very bus.

We didn’t stay in Worcester for long. According to another piece of family folklore, my dad could drive anything – cars and buses, coaches and trucks, huge articulated lorries. If it had wheels and an engine, he was fine with it. As a result, within a couple of years of my sister’s birth, Dad had found a new job. A better-paid one – which was key, given that he had a young and growing family – as a driver for BEA at Heathrow Airport.

We moved into a big sprawling semi in Hayes and Harlington, which was obviously convenient for Dad’s work at the nearby airport, but was also elderly and in need of tarting up. Which Dad of course did. Once again I have an enormous sense of pride in my father; he really did seem able to turn his hand to anything. Replacing windows, making furniture, painting walls, creosoting fences: there never seemed to be a day when he wasn’t busy doing something. In the meantime, we kids played in the garden. This had an Anderson shelter, a relic of the Second World War, which, though it had long since been filled in with earth, provided us with our very own adventure playground: a grassy hummock to scramble over, a launch pad for our bikes, a backdrop for whatever games our young imaginations could conjure up.

* * *

Having sent in the entry form for the Silverstone half marathon, there is no turning back, and even if there were, I decide to seal the deal by announcing that I am taking part in it on Facebook, for good measure. As with telling all your mates you plan to give up smoking, putting it out there means there is NO WAY I can back out of it now.

For all my efficiency in telling the world what I’m up to, though, it’s still going to be quite a leap of imagination to actually see myself completing a half marathon. And if my plan is to have any sort of credibility – not least with me – it’s a leap I’d better start getting fit for.

Which means training. And training means several things must happen: hours of training itself, yes, but I must also cultivate a mindset of self-discipline and a big stock of dedication. Though in reality, I don’t have a clue what I need to do to prepare. Note to self: so hurry up and find out!

DECEMBER (#ub2757e0e-e927-5461-a178-28c8a816e26e)

6 December 2011

Number of shopping days till Christmas: 19.

Number of days till my 49th birthday: 3.

Ergo, number of days till my 50th birthday: 368.

Number of challenges that need to be completed per day, therefore, on average: 0.137741.

Number of challenges that have actually been completed per day, on average: 0.000000.

Well, I’ve been busy training, haven’t I? I have just, in fact, returned from a 5-mile training lap around the town. And I have decided upon a new motivational slogan: if I can make it around Wellingborough, I can make it anywhere. (Which will obviously, of necessity, include Silverstone.) No, it doesn’t have quite the same ring as the lyric from ‘New York, New York’, but it is what I believe to be true.

It’s all about motivation, obviously. The way the weather is looking right now, I might not get another chance to get out and train till after Christmas, so it feels good to have got the laps I have done in the bag. Admittedly, a half marathon is 13 miles, not 5, but in terms of conditions there’s no contest. What with the state of the roads and pavements, pot holes, broken kerbs – not to mention countless badly parked cars – just negotiating the route of my training lap is a major challenge. It’s also pretty hilly, which, in a wheelchair, is hard on the arms, so all things considered (and wheeling round, I’ve had plenty of time to consider) 13 miles on a perfectly smooth, level racetrack doesn’t daunt me quite so much now.

I Skype my brother Gary, who lives just outside Frankfurt in Germany. He studied performance sports at school and still plays squash at a high level, so is the ideal person to give me training tips and encouragement. He tells me to eat carbs, drink plenty of water, practise having a positive mental attitude and generally live a life of such wholesome sobriety till March that as soon as we’re done I feel a compulsion to crack open a large beer.

10 December 2011

Number of years on the planet now: 49. And I don’t feel a day older than 77 (post-training complications – i.e. I hurt).

Number of challenges completed: Erm … still have not quite done any yet.

However, bottles of good Merlot consumed: 1.

I was 49 yesterday, and the thing that most sticks in my mind is that I now have just 364 days to complete all 50 challenges, or else I am going to look something of an idiot. It was a nice birthday – though we dubbed it something different. As Lisa and I dined from the Christmas lunchtime menu at the Beckworth Garden Emporium (and why not? They have a cracking restaurant) we decided we’d call it the Mantisweb staff Christmas party, Mantisweb being the name I’ve given my new business. Which of course gave us licence to misbehave generally, though neither of us actually photocopied our bottoms.

My birthday over – Christmas isn’t allowed to begin until it is – the festivities are coming around super-fast now, and Lisa and I still don’t know what to get the kids. With all my redundancy pay already allocated to pay the mortgage, money’s tight, so it’s not going to be an extravagant affair this year. I find I don’t see that as a bad thing, particularly. Perhaps it’s good to keep things a little simpler – more like the Christmases of my own youth, when there were only three TV channels, there was no 24/7 scheduling, and a snowball wasn’t just something you lobbed at your mates but some foul, yellow, frothy thing your mum drank. Well, my mum did, anyway, and whichever way you look at it, I can’t help but look back at Christmases past and wish Christmases present were just a little more like them.

* * *

Despite us having very little materially then, compared to today’s festive excesses, it really did feel like a time of plenty. It was a time when not only did the dustmen get a crate of brown ale from Dad, as an annual thank you, but also the entire contents of the drinks cabinet (actually the sideboard) were brought out on top, dusted off and arranged, like a help-yourself bar at a wedding reception. It was a time of corner-to-corner paper streamers in the living room and glittering skeins of tinsel for the tree. Which was, of course, a real one.

It’s a cliché now, but we did all really get tangerines in our stockings, plus chocolate (festive chocolate, obviously: golden coins, or Lindt kittens) and a pack of playing cards or some little toy. I remember one year getting a yoyo and not having a clue what to do with it, so I just swung it round and round my head, nearly taking out the light fittings.

The presents done – a military exercise, involving four piles, four anxious children and then one unholy scramble – we children would accompany Dad, playing family postman, delivering gifts to all our relatives while Mum got on with lunch. And what a lunch it was, because Mum was a fantastic cook, and made the best onion bread sauce on the planet, bar none.

The drink of choice on Christmas Day chez the Hollands was Pomagne. A poor man’s champagne, made from cider, it felt like the height of sophistication – or would have, had Dad been more adept at handling it. It was always a tense moment when he attempted to get the cork out, ever since the year when it flew out, headed for the ceiling at great velocity, came back down and landed in the gravy boat, propelling most of its contents all over my brother Mark.

Lunch over – and perhaps as a result of the Pomagne – Mum would always tell her annual Christmas joke. Which was a pretty ropey one, but, in keeping with the spirit of the occasion, we didn’t care: we’d roll about at every telling.

Mum: ‘What did the elephant say when the mouse ran up its trunk?’

Us: ‘We don’t know. What did the elephant say when the mouse ran up its trunk?’

Mum (pinching her nose hard together with her thumb and forefinger and speaking in a squeaky voice): ‘Hmm! I suppose you think that’s funny!’

You’re right. You probably had to be there.

But for all the joy of my childhood, it wasn’t without its worries. Though I was unaware of it, my parents were becoming anxious about me. I must have been around three or four when they first started noticing problems with my toes. They would curl up every time I tried to put my feet into my wellington boots. I was OK with shoes and sandals, but there was something about the angle your foot is at when you feed it into a wellington boot that gave me problems. Once my toes were inside, I couldn’t seem to straighten them out by myself. My parents also noticed that my gait wasn’t quite natural; I would walk in a way that perhaps I would today describe as ‘hopeful’, flicking my lower legs forward, rather than placing them as you would normally, in the hope that the heel would hit the ground before the toes did. If the latter happened (and as I grew, this became more and more evident), the result – flat on my face – sure wasn’t pretty.

I had no idea how much this concerned them, obviously. My toes did what they did, and my gait was what it was. I felt no frustration about any of this; I just worked around it. I was only little, after all. I knew no different.

I had other things on my mind, in any case. While Mum and Dad tried to rationalize their concerns by saying my problems were just part of me ‘growing up’, I was much more concerned with that other big growing-up thing: not being a baby any more, I couldn’t wait to start school. With two big brothers already there, I was aching to join the party. I didn’t want to be stuck at home with only my little sister for company; I wanted to be where the big boys were.

When my brother Gary announced one morning that today was the day, my excitement at going knew no bounds. But I was destined for disappointment. The first disappointment was the news, once we arrived there, that I wouldn’t be joining my big brothers in the junior school as I’d expected. I would have to go elsewhere – well, a whole playground away, anyway – as I was only old enough, apparently, to join the infants. The second disappointment was that as soon as Mum left, all my confidence went scuttling away with her. Within the space of a few hours I’d had all the stuffing knocked out of me; I felt anxious, alone and very lost.

Thankfully, the feeling didn’t last. In fact, another revelation was that the business of making friends there was unexpectedly straightforward, and seemed to consist of the simplest of exchanges.

‘This your first day?’ a boy said.

‘Yes,’ came my mumble.

‘OK. Wanna play football?’

Job done.

Best of all was that it seemed to work with almost everyone (bar the girls, of course). You played football with someone and you had a friend for the rest of your natural life. Or at least for the immediate future, till the bell went, which, as with any four-year-old, was as far ahead as I generally thought.

But the problems with my curling toes weren’t going away and had now started to impact on my getting dressed for school. It had begun to take me so long that Mum even began stressing that I’d become phobic about going for some reason.

Nothing could have been further from the truth. I loved school. But certain aspects of it were becoming more challenging for me, clearly. And though, once again, I wasn’t really aware of this myself, my parents became increasingly concerned. Their concern mostly centred on my gait. I didn’t walk like my siblings and no one knew why – and my gait definitely wasn’t getting better. After a couple of months of this, my mother made her mind up: she would take me to the local clinic to see a doctor.

I still remember my incomprehension about this visit. I wasn’t feeling sick, and nor did I have a sore throat or a rash, but even so, I was being taken out of lessons. Why was that? I was no less confused when we got there and the doctor immediately took off my shoes and socks and began tapping my ankles with a little rubber hammer.

But it was my mum who was most confused when, the foot inspection over, the doctor turned his attention to my arms and hands. She was just about to ask him what my hands had to do with anything when he let out a loud and alarming ‘Hmmmm …’

‘What?’ asked Mum anxiously.

‘Hmmm …’ said the doc again. ‘I think young Nigel here needs to go and see a specialist.’

He then began talking over my head, to my mum, while she helped me put my shoes and socks back on. I didn’t understand much of what he was saying – though I soon would – but the gist of it seemed clear: ‘I don’t actually have a clue what’s wrong with your son, Mrs Holland, so I’ll pack him off to someone who might.’

On the way home, feeling as you do after a visit to the doctor (a little bit relieved, a lot brave, a tad martyred), I hoped – even expected – that there might be something in it for me. A small toy perhaps, a bag of sweets, a penny lollipop. But I got nothing. Mum was never one for over-indulging her kids. I got deposited straight back at school.

FEBRUARY (#ub2757e0e-e927-5461-a178-28c8a816e26e)

8 February 2012

Number of inches of snow dumped on Wellingborough in January: Easy – more than enough to prevent me from getting out.

Ergo, number of challenges so far completed: Still 0.

However, number of challenges attempted today (finally): 1 – ‘Donate blood.’

But number of challenges actually completed today: Another big fat 0. Oh, and I also got wet.

Well, that was a great start, I don’t think. You might have noticed that, despite a flurry of early enthusiasm and activity, there is nothing recorded here for January. Which is because nothing actually happened in January. Yup, that’s correct. Nothing whatsoever. Yes, we ate, slept and did all the day-to-day things that needed doing, but in terms of My Big Important Project, not a thing.

I know I shouldn’t beat myself up too much. The bottom line is that wheelchairs and snow do not mix – unless you count regularly landing on your own bottom line among your list of favourite pastimes. And it’s not as if I haven’t been getting things under way, making phone calls, sending emails and doing research.

But I’m frustrated because apart from signing up for the half marathon (which does not mean actually doing it, of course, however many training laps I put in before Christmas), becoming a blood donor was to have been pretty much my first completed challenge, and the one I was most keen to get over with.

Except I haven’t got it over with. Which is infuriating, as the day began so positively. Well, I say positively, but there wasn’t really anything positive about it. Just naked fear. Because actually I was terrified.

‘So why are you doing it, then, Dad?’ Ellie wanted to know. It was a reasonable enough question. Though I was pretty sure that by now she understood the concept of the list and why I was doing it, I wasn’t so sure she’d embraced the idea that it might include doing things I didn’t want to do.

We were all finishing breakfast, before the kids left for school. Though I say ‘we’, I couldn’t eat a thing, because I was off to become a blood donor in less than an hour, the thought of which had completely robbed me of my appetite.

‘Because I’m confronting my fears,’ I said, probably rather grandly, in an attempt, as much as anything, to psyche myself up for it. ‘That’s what you do,’ I went on. ‘That’s what makes it a challenge. That it’s difficult is really the whole point. If it was easy for me, it wouldn’t be challenging, would it? If it was Mum doing it, say,’ (Lisa’s a long-term blood donor) ‘it would be easy. But because I have a phobia –’

Ellie looked confused now. ‘What’s a phobia?’

‘An irrational fear,’ Matt supplied. ‘Like when you’re really scared of snakes or spiders –’

‘There is nothing irrational about being scared of snakes and spiders,’ Amy chipped in. ‘Not if they’re cobras or rattlesnakes or black widows or something …’

‘And yours is needles?’ Ellie asked. ‘Needles being poked in your arm?’ She demonstrated on herself for me. ‘And then sucking all your blood out …’ she added, warming to the idea now. ‘A bit like they’re vampires?’

Which wasn’t the best image to be starting the day with, frankly. Twilight has an awful lot to answer for.

‘Not like vampires,’ said Lisa, presumably seeing I was turning green now. ‘Nothing at all like vampires, in fact. No, it’s done by nurses, and they’re very, very gentle. Dad will hardly feel a thing, because they’re also very good at it …’

But still a lot like vampires, even so.

* * *

It’s not surprising that I have a phobia of needles. From the age of five, and throughout my childhood, they were coming at me from all angles.

My first foray into a world that would become painfully familiar happened just a few weeks after my visit to the GP, when a letter arrived requesting my presence at an appointment that had been made for me at Guy’s Hospital in London.

Being so small still, I didn’t have much idea what was happening. Though I’m sure Mum and Dad told me, I have no memory of making a connection between my bendy toes and the trip to the big city. Going to London was, and would continue to be, synonymous with only one thing for me: a trip to go and visit my Auntie Betty.

My aunt and uncle lived in a sprawling housing estate just off Abbey Road, and I’d go and stay with them at least once every summer. I loved going to visit Auntie Betty and Uncle Gerry. Together they ran a successful stock car racing team, which made them terribly exciting to be with. They would travel all around the country, to race their car in the national championships, and we’d set off to whichever venue we were headed for in an enormous coach that they’d converted from the standard passenger variety into something that, in its day, would not have seemed out of place in a Formula 1 paddock. It carried the stock car on the back and the inside had been adapted so that we could not only sit in it but also sleep in it.

Trips to Auntie Betty’s were the genesis of what would become a lifelong passion for motorsport, and from a very early age, one of the highlights of travelling to London was the point when we’d go through a long tunnel on the A4, and I got that tingle of anticipation, knowing we’d soon be there.

This was different, though. And the big difference that sticks in my mind was that rather than end up at Auntie Betty’s, as usual, we arrived at a scary place, full of incredibly high buildings. In reality not so enormous – hardly the Manhattan skyline – but to little me, they seemed so tall that they blocked out the sun. There was noise, too – so much noise. So many car engines, and bus engines – so many horns blaring all at once, as if all the traffic on the roads was really angry.

And barking. I clearly recall the noise of dogs barking. Strange, looking back – we were nowhere near Battersea – but that’s always stuck in my mind.

I also have a vivid mental picture of the inside of the hospital. And an equally clear one of the great men I was about to meet. I had been summoned to see two eminent physicians of the day: a brace of consultants called the McArdle brothers, who were leaders in the field of neuroscience.

My main impression, not surprisingly for those days, was of brown. Unlike the clinically white environments you find in most modern hospitals, the office of the McArdle brothers was a symphony of dark wood: heavy wooden filing cabinets – the contents of each drawer identified with its own white, handwritten label; dark-wood chairs – one for each of them, plus a further three ordinary, dark, school chairs for me, Mum and Dad; and a hefty dark-wood desk with an inlaid leather top. Looking back, the only thing missing from the tableau was a couple of those globe-shaped glass bottles full of brightly coloured water whose function was, and still is, a mystery.

Also in keeping with the fashion of the time, the McArdle brothers – looking rather frightening in their matching white coats – puffed merrily on cigarettes before mounting their attack. I had come to be investigated and they went at it with gusto, putting me through a series of increasingly scary tests. I was prodded and poked, inspected and injected, and at the end of it, the brothers reached their professional conclusion. Mum and Dad had been right: there was definitely something wrong with me. I had some sort of hereditary muscle-wasting condition, apparently, and to be sure they would need to do some tests.

Everything changed for my parents that day. And, looking back, I’m not surprised; it must have come as such a shock. Though the condition was apparently hereditary, there was no history of it in either family, meaning that it must be the result of some random mutant gene.

We returned home, and while I carried on doing all the things little boys did, largely oblivious to my ‘condition’, they could only look on as my muscles became progressively weaker and – having no experience or medical knowledge of what was wrong with me – worry about what the future might hold for me.

Not that my childhood, from that day, was really normal. Though Mum and Dad never allowed me to dwell on whatever it was that was causing my problems (if I became tired after playing, then I rested, but they never stopped me doing anything), it increasingly impacted on my life. This was mostly because life began to be punctuated by interruptions: an endless round of hospital visits, while they tried to better understand what was causing my symptoms. There was obviously no choice but to put up with it all, but hospitals – and everything that seemed to happen within them – soon became the bane of my life. I disliked all of it – in fact, ‘dread’ probably isn’t too strong a word here. What child wants to be in and out of hospital, dragged away from his friends and whatever fun things they might be up to? I particularly hated the seemingly endless in-patient visits to the Hillingdon Hospital and the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in Queen Square. Both places soon filled me with anxiety and fear. And much of the reason for that was that I soon learned I couldn’t trust them. They would say one thing – normally a nice, reassuring thing – and then the exact opposite would happen.

A particularly grim time was at the hospital in Queen Square, where, aged seven, I had to have some nerve induction tests. These tests, which I had to have a number of times, involved an electrode being attached to my ankle, and a needle, with a wire attached, put into my thigh. They would then pass a small electric current through the electrode, so that they could assess the strength of the signal in my peripheral nerves by picking up the signal in the wire.

I think I sort of understood why they needed to do it, but what I never got my head around was what they said every time.

‘Now, Nigel, this won’t hurt,’ they’d confidently assure me. ‘All that will happen is that your leg muscle will sort of “jump”.’

Which it duly did. But what I never seemed to be able to get across to them (and how nice it is to be able to make this point here) was that it was my leg, and actually it did hurt!

As I was so young, and an ‘inmate’, which was sort of how it worked back then, the doctors would gather around my bed and talk over me and about me, and, without my parents around to explain what was happening, my only source of information about what horrors might be inflicted next came by way of updates from the nurses after the ward rounds.

‘They’re going to take you to occupational therapy,’ I remember one telling me during one stay, ‘to be assessed,’ she finished mysteriously. It meant absolutely nothing. What on earth was ‘occupational therapy?’ I could hardly pronounce it, and like all the other unpronounceable words they bandied about, I didn’t like the sound of it one bit.

‘What are they going to do to me?’ I wanted to know. ‘Does it involve “tests”?’

‘Tests’ was a word I could pronounce, but I was anxious about them too. Because experience had taught me that tests almost always seemed to involve needles in some way. ‘No, not at all,’ she replied. ‘Really. It’s nothing to worry about, Nigel.’

But her reassurance, helpful though it was, was short-lived. ‘And after that,’ she added quickly (presumably thinking that if she slipped it in I might not notice), ‘they’re going to take you off to have a lumbar punch.’

This was a new one. And one that I definitely didn’t like the sound of. As soon as the nurse elaborated, I was terrified. OK, so it turned out that it didn’t involve being punched by a tree trunk, but what it did involve – in essence, being punctured by an extremely large needle – sounded even more terrifying. A lumbar puncture is when a needle is inserted into your spinal cord and a small amount of spinal fluid drawn off. And as I lay on the bed, curled into a tight ball – knees to chest, as instructed – I was as petrified of that needle as I could be.

‘All over soon,’ the nurse kept saying, patting my head.

‘And you won’t feel a thing,’ the doctor helpfully reassured me, ‘because I’m going to anaesthetize the area first.’ And, to give him his due, on this occasion he was right. Apart from the initial prick – which obviously I did feel – I felt absolutely nothing, and the only bad bit was afterwards when I had to lie on my back for 24 hours, while enduring the worst headache of my young life.

Much worse, in terms of my increasing phobia, was the endless round of blood tests I seemed to have at Hillingdon Hospital, which was staffed by a rogue gang of vampire medics – it must have been, because harvesting my blood seemed to be a favourite pastime. Looking back, I suppose their fascination with looking at it was for a valid reason: I had an extremely rare disease, which they were researching all the time, and I made an excellent guinea pig and pin cushion.

When I was growing up, little was known about CMT. It affects some 23,000 people in the UK and research into it was a vital step in the process of learning how to manage its manifestations. These are many: foot drop, chronic tiredness, bone abnormalities, muscle atrophy, balance issues, loss of dexterity, fatigue and chronic pain. Though I didn’t know all this as a little boy, obviously, I still felt I had to agree to being a guinea pig. Saying no wasn’t an option – not if I wanted to better deal with my disease. The doctors and scientists needed to know about it and, more importantly, so did Mum and Dad.

My poor parents. While as a child I had to deal with its many inconveniences, they had the unenviable task of steering me through a childhood and adolescence knowing that my nerve function would gradually deteriorate and that I’d more than likely end up with a major disability. They had to cope with the knowledge of what might be ahead for me.

But it was hard to be that guinea pig, however much I knew I had to. The medics took blood from me at any opportunity they got, and with every needle they stuck into my arms, my fear grew – so much so that one day it took three nurses and a doctor to hold me down, so that they could get their standard inch of glistening fluid. ‘Well done!’ they’d say. ‘There we are! That didn’t hurt at all, did it?’

Erm, yes. Yes it did hurt. A lot.

And it didn’t just hurt: it became a source of constant anxiety. Like any other child, I loved my parents and wanted to please them. They were trying to make sense of something no one understood, and naturally – and quite rightly – put their trust in the doctors and scientists who were just starting to get to grips with what CMT was. And having me as a real-life case study (either willing or unwilling) was a central part of amassing the vital information that would, everyone hoped, make my life less challenging. So I would never dream of criticizing my parents for the years of investigations I had to go through. They were doing their best for me. They never did anything less than their best for me. Just as Lisa and I want to do our very best for Ellie. Though thank goodness she’s been born into another time.

* * *

The kids duly dispatched to their various places of learning, Lisa and I cleared the kitchen and then headed into Welling-borough, to the church hall where I had my date with destiny.

Apart from the constant nausea, the sweating palms and the gnawing terror, I was actually feeling quite well prepared. I had done my research. I’d often read about the whole ‘confront your fears’ approach to dealing with a phobia, and had been impressed by the case studies of chronic arachnophobics who, after doing just that, had been completely transformed and would let tarantulas skip merrily along their arms. Encouraged, I’d been for a browse on the NHS website, and, having chatted on the phone to a very helpful lady about the process, and having also covered the potential complications of my disability, I had already registered as a first-time donor.

Today, then, was the culmination of a serious purpose. After all, this wasn’t just about ticking an item off a list. It was about doing it for that warm glow of pride in an achievement – to enjoy the thought that my blood would be going to help someone somewhere; I’d confront my fear and I’d do good. What better example could there be for Ellie?

Even so, as we pulled up outside the church where the mobile service was, all I could think of was how fervently I wanted to just get in, give the blood and then get the hell out of there.

‘You’ll be fine,’ Lisa said reassuringly, as I parked the car in the church car park. She’d been saying it at regular intervals since we’d got up that morning, and though I was grateful – Lisa’s always such a big support when I’m feeling anxious – her reassurance was falling on deaf ears. I probably would be fine, I knew that, but that’s the thing with phobias: you think one thing, but your body does another.

The weather wasn’t helping much, either. There was heavy snow forecast over the coming days, and, perhaps as a taster, or perhaps as a personal portent, heavy rain had fallen overnight. And because a car had parked close to the ramped kerb I needed, my only way into the church was via a deep muddy puddle. Not something that would normally faze me – I’m quite an expert in my wheelchair – but, given the circumstances and my growing sense of impending doom, wheeling wetly through it (while busy cursing inconsiderate parkers everywhere) only added to my sense of foreboding.

Inside the church hall, where the temporary blood-letting – sorry, blood donor – service had been set up, there was little to cling onto that would reassure the average phobic. Seven gurneys, I counted, once I’d given my name and we’d transferred to the waiting area, and on each was a compliant donor, to whom was attached a needle, which was attached to a tube, which fed the donor’s blood, in regular deep-red drips, into a plastic bottle. If there was ever a point to turn tail, this was definitely it; but strangely, though it looked like a scene from Doctor Who, there was something about the vampires – sorry, nurses – who were running this particular show that made the whole scene look unexpectedly calm and peaceful. And as a bonus, there was no one actually screaming. To my surprise, I felt a sense of relative calm begin to descend.

‘You’ll be fine,’ Lisa whispered again, seeing my gaze and misreading the effect it was all having on me.

‘You know what?’ I whispered back (it was that kind of place – hush felt obligatory). ‘I am actually looking forward to doing this, now we’re in here.’

‘You are?’ She didn’t look convinced.

But there was no time to wax lyrical about my new-found inner calm, because my name was called then, and we went off to a small temporary cubicle, where a nurse bearing a biro wanted to know all about my condition. This was a surprise, as it had been discussed at some length on the phone, as well as being detailed on the registration form.

Risking a quip, I explained that my ‘condition’ was ‘sitting down’, which she obviously found so unfunny that she went to great lengths to explain that since she personally didn’t know anything about my real condition, she couldn’t take blood from me without a letter from my doctor.

‘But I’m absolutely fine to do that,’ I explained. ‘I’m not ill.’ I explained again that this had already been covered over the phone.

But she was having none of it. As they didn’t know that, even if I did, I would need to get the letter before they could risk taking blood from me. And that was the end of it. I would have to go away and then come back again the next time the blood donor service was in town.

‘Isn’t there any way around this?’ I asked her. ‘Coming here’s been a really big thing for me today. It’s one of my challenges, you see.’ I told her about my 50 List, half hoping she might have seen it in the local paper; I explained how it worked, and what I was doing it for. ‘And this one’s particularly dear to me,’ I finished, ‘because of my phobia of needles. I’ve had it since I was a child, and I was determined to beat it. Meet it head on –’

But I could tell from her expression that there was no way I’d be meeting it today. ‘You have a phobia?’ she said. ‘Oh, well, in that case, we wouldn’t take your blood anyway.’

Apparently they felt it wasn’t a very good way of ridding someone of a phobia. So that was that. They all apologized, and I wheeled myself out again, my needle phobia still there to fight another day.

‘Never mind,’ said Lisa as we drove home, mission not accomplished. ‘You’ll just have to think of a new challenge to replace it. There’ll be something …’

We lapsed into what we hoped would be a productive, thoughtful silence.

And it was. An idea suddenly came to me. ‘I’ll try wood turning.’

‘Wood turning?’ Lisa asked. ‘Where on earth did that come from?’

‘Erm … it’s dexterous? It involves using my fingers? It’s probably tricky?’

Definitely tricky, if my childhood exploits in woodwork class are anything to go by.

‘And there’s a thought,’ I said testily. ‘Let’s hope I don’t rip my finger off on the lathe and require pints and pints of blood to save me, eh?’

Lisa smiled. ‘You’ll be fine,’ she said firmly.

14 February 2012

Number of challenges still to be completed: Er … still 50.

But number of challenges that are almost definitely going to be happening less than 10 days from now, all at once, and ON THE BBC no less: A big fat 3! Hurrah! Now we’re talking.

Just put down the phone to a man called Matt Ralph. He is a BBC television producer. Am amazed. What a difference a day can make, eh?

Everyone makes New Year resolutions, don’t they? Give up drink. Lose a stone. Read War and Peace. Be a Better Person. But having already made 50 of them before Christmas – way more than most people – come the New Year, I didn’t need to do much resolving. No, what I needed to do was get on and actually do them, and suddenly here we were, edging into spring, and barely anything had yet been done, bar a failed attempt to get someone to take some blood. I was beginning to feel that my deadline, 9 December 2012, my 50th birthday, was breathing down my neck.

I hadn’t even been able to get out and do much training for the half marathon, my initial burst of enthusiasm having been rained on from a great height. Frozen rain, in fact: the much forecasted, much anticipated and now interminable snow. And there are only so many times you can make a circuit of the coffee table before losing the will to live and/or becoming so dizzy you pass out.

‘You need publicity,’ my friend Simon Cox said to me firmly. It was a Tuesday, the kids were in school, and he was over to discuss business. He was a client now, as well as a close pal of mine, and once we were done discussing e-commerce solutions for his company, I’d showed him the new 50 List website I’d created – my pet project once the kids had gone back to school.

I’d also by now set up a JustGiving account. My mentioning the list on Facebook had brought a flurry of enquiries from friends wanting to know where and how they could make donations – and, more importantly, who I wanted to have them. So it made sense to make things official by putting that information on the website too, explaining that anyone who felt inspired to could donate direct to CMT United Kingdom, the charity that was the first port of call for people with CMT, myself obviously very much included. The money would then be split equally between ongoing research and supporting youngsters, like Ellie, with the condition.

I’d set myself a pretty ambitious target as well – to raise £5,000.

‘I know,’ I said to Simon. ‘It’s a lot to aim for, isn’t it?’

‘Which is why you need to get it out there,’ he said. ‘Fire people’s imaginations about it. Give them a chance to get involved. Local businesses even, maybe. It’s the sort of thing the local papers will jump on too, believe me. That might lead to sponsorship – financial help and so on.’ He pointed to some of the more outlandish challenges I’d set myself. ‘Which, by the look of this, you’re really going to need.’

Perhaps because I’d always thought I’d fund the list myself, it had never occurred to me to involve the local papers in what I was doing. I said so.

‘Are you mad?’ Simon laughed. ‘It’s January, remember – nothing doing. They’ll be all over this, trust me. Take a look out of the window. I reckon they’ll leap on any story they can lay their hands on right now that doesn’t need to include the word “snow”.’

I did as instructed and agreed he was probably right. I’d leap on anything that didn’t involve snow at the moment. Much as I didn’t want to be a grump and a killjoy, snow and wheelchairs were incompatible: that was a fact of life.

‘Seriously,’ he went on, ‘they’ll be all over this anytime. Tell you what. I have a friend who knows a journalist down at the Herald and Post. Let me have a word with her. See if she can get him to do a piece on it. Spread the word a bit for you. How about that?’

‘You think?’ I said. ‘You really think he’ll be that interested in all this?’

Simon grinned. ‘Nige, mate, you really don’t know what you’ve got here, do you? Just you wait and see, mate. Just you wait.’

And it wasn’t a very long wait. It was around 24 hours, give or take – no more than that – before a journalist from the Herald and Post was indeed on the phone wanting to talk to me and, having asked me a few questions about what I was up to, wanting to know when he could send their photographer round and get some pictures of both me and, he hoped, Ellie.

She was typically bemused at the prospect of being in the paper.

‘But why?’ she kept asking on the morning of the shoot. ‘Shoot’ – in itself a heck of a concept to get my head around.

‘So that everyone can hear about what I’m doing and why I’m doing it,’ I explained to her. ‘To spread the word, and I hope raise money for CMT.’

‘Yes,’ she said, ‘but why do they want a picture of me?’

‘Because you’re one of the main reasons Dad wants to do it,’ explained Lisa. She was brandishing a duster with an expression of mild fanaticism. She had been all morning. Where dust was concerned, she’d be taking no prisoners. There was no way her living room would be featured in the local paper looking anything less than squeaky clean and perfect. I wouldn’t have been surprised to be given a quick buff and polish myself. She’d already given the dog the once-over.

‘But you don’t have to if you don’t want to,’ I added quickly. Although I was doing this to inspire my youngest daughter, there was no way I was going to make her do something she didn’t want to do. So if she didn’t want to do it, then so be it. Ellie is feisty and self-possessed, but she is also quite shy. And the last thing I wanted was for any of this to make her stressed, or for her to feel that she was being pushed into the limelight.

But she surprised me. ‘OK,’ she said. ‘I don’t mind. It might be cool.’ Then she hurried off upstairs to get changed into her favourite Minnie Mouse T-shirt.

Then, as they probably became sick and tired of saying in the papers that particular winter, the whole thing, to our amazement, snowballed. The piece appeared in the paper the next day – it even had its own front-page intro – and the phone, as a consequence, began ringing.

First it was a news agency, SWNS, who expressed great enthusiasm for handling my ‘story’, which was something I’d never even thought of it as. It was a project, my project, that was all. But they disagreed. It was very much a story, they told me, and one they were keen to put out to the nationals, to see what they might make of it, too.

So they did, and they came back to me the following morning to tell me that it had also now been published in Metro, the Sun, the Daily Mirror and the Daily Telegraph. Not huge pieces – only a few column inches in most cases – but I was flabbergasted, as was Lisa, and all the kids.

The days that followed were no less surreal. In fact, they rank among the craziest and most overwhelming I’ve ever experienced.

Next came the calls from various radio stations. Would I be prepared to talk about The 50 List on air? Absolutely.

Then magazines. Would I be prepared to do interviews with them? Naturally. Then TV – 5 News, to be precise. Would I be prepared to travel down to London to be on their programme and tell the world how the idea of The 50 List had come about?

By now the phone was ringing almost constantly. No sooner had I hung up on yet another enthused researcher, and gone into the kitchen to give Lisa the latest update, than – brinngg brinnggg! – straight away it rang again.

‘Can you believe this?’ I asked Lisa every time it started up again. ‘So this is what 15 minutes of fame feels like, is it?’ I’d never dealt with anything quite so manic in my life.

Happily, the news agency stepped in to help us out, and became the contact to whom I could direct all the callers. This left me and Lisa free to think about what we could and couldn’t do.

The reality was that going down to London, to Channel 5, would be something of a mission. It would mean an incredibly early start and a complex journey via public transport; and both the prospect and the expense were a bit daunting. But it would potentially be a brilliant way to help my cause – and, I hoped, help me reach my fundraising target. Should I go?

I was still dithering when the email came in this morning – the email that topped them all. The big one.

Hi Nigel,

I’m a director working for The One Show at the BBC. I read an article about you and your daughter Eleanor in today’s Metro. I was sorry to read about your daughter’s diagnosis but it sounds like you are doing something really amazing to inspire her.

I wondered if I might be able to find out more about your challenges with the view of possibly helping you set up and complete some of them and film a piece about it for The One Show? If this sounds like something you might be interested in please feel free to get in touch. I’ll be happy to answer any questions and we can discuss what is possible and what is not.

Thanks for your time and hope to hear from you soon.

Best,

Karolina

I got straight on the phone, which was how I got to talk to Matt Ralph. And though I still can’t quite believe it, it’s all fixed. On 23 February I get to complete not one but three of my challenges: I’m going to do an indoor skydive, take a 4x4 off road and go powerboating as well. Now we’re not only talking the talk, as they say, we’re walking the walk, too. Well, sort of.

* * *

Not every test I had during my childhood involved needles and pain. Sometimes the tests were just very odd. One time, when I was around 14, I was summoned back to the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in Queen Square, London, where they wanted to glue a load of electrodes to my head, which would then be connected to a large machine. Naturally, by now, I was wary of anything that anyone in a white coat did, so it took the doctor some time to convince me not only that he wasn’t going to kill me but also that there wouldn’t be any pain involved.

‘You won’t feel a thing,’ he kept telling me. ‘You can’t. Because brains can’t feel pain – did you know that? All that’s going to happen is that the machine is going to read all the messages that your optic nerve sends to it.’

Which sounded worrying in itself, but I had no choice other than to go along with it, and sat patiently while he prepared me for his investigations. First he used a chinagraph pencil and a tape measure to make marks on my scalp where the electrodes needed to go. He followed this up with globs of glue, to which he stuck small white discs, to which he then connected a load of wires. These wires, around a dozen of them (one for every disc), were connected to a large (and I do mean large) metal cabinet, the front of which was a sea of lights, dials, switches and oscilloscopes, none of which, he hastened to add – once I was finally connected to it, and frankly terrified – were out to do me any harm.

The only harm done that day was to my sanity. I had to stare at a moving dot in the middle of a chequered board, and that was it. Nothing else. For an hour. I’ve never sat and watched paint dry, but I imagine the two are similar. Certainly my dad, who was supposed to be there for moral support, soon closed his eyes and had a sneaky 40 winks.

But as with any kid, there was a feeling that was much worse than boredom, and I was about to have my first taste of it: acute embarrassment. With the first test done and my cables detached from the machine, we were instructed to go off and get some lunch, before returning for some more tests in the afternoon. It was summer, I recall, and with no facilities on the premises, Dad decided the best thing would be to go and get something to eat at the pub on the nearby square and, as the sun was shining, to sit outside. Which was all well and good, except that with my bunch of cables – temporarily bound and now neatly taped to my shoulder – I still looked like something from a science fiction movie. And a scary one, if the stares I attracted were anything to go by, which seems a bit harsh, in hindsight, considering they were probably all nurses and doctors and must have been used to such sights. My humiliation only subsided when I saw another boy walk by and noticed that he had the same bunch of cables glued to his head. Had we been older, perhaps we would have shared a sympathetic exchange of nods. As it was, I could only count myself the lucky one, because he had it worse: he was in a dressing gown as well.

But not all my experiences of hospital were negative. While most of them involved pain, stress or ritual humiliation, sometimes they were actually very joyful. By the time I was 16 my brother Mark was into motorbikes, as were his mates, and when I was an inmate in the hospital for some more tedious tests a while later, a bunch of them decided to come and visit me. I was up on the second floor, but even so, you could hear them arriving before you could see them and the sound of them parking was fantastic, just like a fusillade. I looked out and there they all were, leather clad and looking impossibly cool. I couldn’t have been more thrilled to see them.

Even nicer was the reaction of the nurses and other patients, when they saw the six young men in biker gear striding down the ward. No one could say anything, of course, but their faces were a picture. When they all left – having been perfectly polite, and not outstaying their welcome – I rushed to the window again, to see them roar off as one. I felt so proud, and so subversive, that I thought I’d burst.

16 February 2012

Breaking news: The jigsaw has landed!

Though, to be honest, it’s not the one we’d originally planned on doing. The original, as per my list, was a whopping 5,000-piece job, which we’d borrowed from our friend June Pereira. It was a fine art image, which came with the rather grand title of The Archduke Leopold Wilhelm in his Picture Gallery in Brussels. It looked complicated – which, in jigsaw-land, actually made it easier: the more complex the picture in terms of shapes and tones and colour, the less likely it is to drive you to insanity. It’s the seascapes and landscapes that really vex the committed jigsaw fanatic, which I am not. So it was a no-brainer in that sense.

But I could tell right away that it was going to be impossible: not because it was too hard, even if Ellie found it a little fusty, but because I hadn’t factored in the sheer size of it. It was enormous! Not only would it not fit on the designated coffee table; it wouldn’t fit on the dining table, either, and that was assuming that we’d be happy – which Lisa obviously wasn’t – to have the table out of commission till the thing was finished.

In the end, Ellie and I opted for a 1,000-piece puzzle: a montage of famous steam engines (the Flying Scotsman and the Mallard, among others) which we think Lisa might have bought me years ago and which, as yet unopened, was gathering dust and cobwebs in the loft. And though it was no closer than poor old Leopold to her favoured subject areas of One Direction, One Direction and … let me see now … One Direction, Ellie pronounced it an acceptable replacement.

Doing the jigsaw is one of my more specifically CMT-targeted challenges; and not just for me but for Ellie, too. With CMT it’s not just the lower limb muscle groups that are affected. It attacks the muscles of the arms and hands as well. This obviously has enormous implications for dexterity, and for both Ellie and me muscle wastage, and the accompanying loss of strength, mean our fingers can’t do the things most people take for granted, such as unscrewing bottle tops or lifting heavy items like saucepans, or even something as simple as picking up something off the floor after losing grip on it. For me, with decades of practice at trying to find solutions, it’s all about maintaining independence. Not being able to tie my own laces or put socks on or do up my top shirt button are all things that I have grown to accept are going to be beyond me on some days, because the weakness varies enormously day to day. But I’ve found solutions – electric can opener, electric jar opener, button doer-upper. Sometimes I just work out different ways to do things without any adaptations or devices. It definitely helps focus the mind on what I can do.

For Ellie, though, just starting out on the same journey, the challenges are still exactly that: challenging. We are incredibly lucky in that her school makes every effort to include her in all activities, but she still has to find ways of doing what others can and she can’t. Her dexterity, though better than mine, is already causing her problems, and she’s on the road, just as I was, of having to come to terms with the inevitable: that it’ll be a process of continual deterioration. She is already having to learn to do all her writing on a keyboard – something that’s perhaps not such a problem as it was back in my day, as kids these days, after all, are so competent with computers – but, as with so many things that she can’t do but the rest of her peer group take for granted, it obviously marks her out, and that frustrates her.

As will this jigsaw, I don’t doubt! It’ll frustrate us both. And it’s meant to, since it relies on the ability to pick up really tiny pieces and then slot them into very precise places. Daunting, but, as I hope to prove to Ellie, still achievable. It will just take time and commitment and lots of patience, and at the end of it, boy, will we both feel proud.

But even if we don’t – even if, in the end, it defeats us – Ellie will still have learned a very valuable lesson: that it’s all about giving things a go, having a stab at them. That’s the key to having an exciting and experience-filled life.

Tonight being a Sunday night we decide to get stuck into it, while Lisa is in the kitchen ironing school clothes for Monday morning and Matt and Amy are occupying themselves upstairs.

‘Let’s see who can find the most edges the quickest, shall we?’ I challenge Ellie, as we sit down together on the floor by the coffee table.

I say ‘sit’ but that probably gives the wrong impression. What I actually have to do if I want to be anywhere lower than my wheelchair is ‘transfer’ from it – which all sounds very measured and controlled. Which, of course it is. What I like to call ‘controlled falling’. So I whump down, and immediately see a tactical error: I’m going to have to do this every single time we work on it, since the coffee table is too low for me to do anything from my chair.

But so be it. It’s either that or relocate back to the dining table, and now we’ve started … And, hey, it won’t be for long.

It’s already dark outside, the remaining snow a silvery carpet in the back garden, and sitting here with Ellie, the two of us working at a shared endeavour, feels exactly the right sort of thing to be doing. Something to keep us occupied for the few remaining weeks till spring comes along. And I don’t doubt, looking at the box, that it will take us all of that.

‘Dad, I will, of course,’ Ellie says with conviction.

And, since she’s probably right, I’m not about to argue. Together we carefully pour the pieces into a heap in the centre, taking care not to let any spill onto the carpet, our dog, Berry (named by Ellie – being the youngest, she got her way there), not being fussy when it comes to unexpected potential food gifts. And yes, cardboard does fall into that category. I don’t get much in the way of further conversation after that as Ellie, being Ellie, is too busy trying to beat me. In only minutes she’s amassed an impressive pile in front of her – a pile that I notice is bigger than my own.

‘There,’ she says, as she pushes across a row of four she’s already slotted together, niftily outranking the first corner piece I’ve just unearthed. ‘Can we finish it tonight?’ she adds, lining her handiwork up along her edge of the table. ‘I bet we can, Dad. This is going to be so easy. Easy peasy.’

‘That would be great,’ I agree. ‘But I think it might take a little bit longer.’

Around three weeks, I decide. Three weeks, tops.

* * *

As my condition progressed, so did the wastage of the muscles that had prevented my toes from straightening out as a little boy. So much so that by the time I was eight or nine, I was constantly falling over.

There’s nothing positive about falling over, ever. Though it often made for unexpected entertainment for my classmates, for me it soon became the bane of my existence, as there was never any warning about when I’d next keel over. One minute I’d be walking along happily and the next I’d be flat on my face – literally. There was hardly a day that went by without my sustaining some sort of injury – usually a fat lip or a bloody knee.

I hit the dirt so many times in my formative years that it’s a miracle, looking back, that I’m not a criss-cross of ageing scars, with a nose like that of a battle-hardened prize-fighter. As it is, I got lucky, because my nose is still intact – or perhaps it was the copious application of Germolene and ice packs and plasters that saved me. I only have to get a whiff of that pungent pink ointment to be transported straight back to my primary school playground; to the feel of grit embedded in my palm, the tears welling in my eyes and the suppressed giggles of my mates, who couldn’t stop themselves. The girls, on the other hand, being more sympathetic creatures, would gasp in shock at what had happened, and disapproval, while some teacher or other ran to the rescue.

The reason for this sudden increase in falls was a condition I’d now developed called bilateral foot drop. If you can imagine losing all the muscles that surround your feet and ankles, the resultant floppy appendages – which they’d be, should you try to flap them around a little – will give you an idea of just how infuriating my feet had become. And once a foot doesn’t do what it’s supposed to – i.e. adopt the angle you tell it to – falling over becomes the easiest thing in the world.

But if my pride was wounded by having become someone who could no longer walk properly, that was nothing compared to the alternative I was given: a set of orthotic boots and calipers.

Most kids who grew up in the 1960s will remember calipers, mostly because at that time polio was still a significant problem in the UK. By the beginning of the decade, of course, vaccination had become widespread, but almost everyone knew one kid who clanked around in calipers as a result of having contracted the disease. (I always recall the first time I saw Ian Dury, perhaps the most famous musician of the modern era to be afflicted by polio. I remember thinking two things: what a brilliant bunch of pop songs he’d written, and how did he stop his calipers from squeaking?)

Calipers are designed to support the lower leg, and back then they consisted of a heavy, orthotic ankle boot (which looked very much like the kind of footwear Frankenstein’s monster favoured, on account of its thick sole and bulbous, rounded toe cap), which contained a pin in the heel that connected to a pair of twin steel posts that ran up either side of the leg. These were attached at the top to a leather strap that sat just beneath the knee and could be adjusted to sit snugly around the calf. At the base of the steel bars there was a spring mechanism. This was what would allow my feet to extend, while at the same time, when I lifted my foot from the floor, pulling it back up to prevent foot drop and, therefore, all my falls.

Despite being made to measure, the orthotic boots – which came in black and brown (which was at least one more colour than Henry Ford offered, I suppose) – were extremely uncomfortable. And once fitted up with the calipers (they weren’t the easiest thing to get on and off, either) even more so. Yes, they did their job – they kept my feet at right angles and prevented them from doing the dirty on me – but they also made me walk with a curious, Woodentops-style, stiff-legged gait; so while my older brothers were buying all sorts of trendy footwear in town, I had to endure the indignity of spending my time – in school and out of it – looking like Frankenstein’s monster. At least from the knees down; from the knees up I tried to compensate madly, by adopting a winning smile. Though, given the discomfort, this was probably more of a grimace.

From the day that I donned those boots and calipers I felt different. I was suddenly, and irreversibly, conspicuous. Yes, I could walk around now without fear of falling flat on my face, but with the ugly footwear, the creaky calipers, and the steel bars that fitted attractively to the back of the boots, I now realized that I wasn’t like any other child I knew. While the falls were just a part of me – and, let’s face it, all kids fall over sometimes, some of them often – there was nothing else about me that made me seem any different to any other kid. But now there was. The boots singled me out.