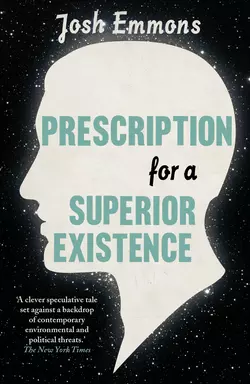

Prescription for a Superior Existence

Josh Emmons

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современные любовные романы

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 155.72 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ‘A major-league prose writer who has fun in every sentence’ Jonathan Franzen‘A clever speculative tale set against a backdrop of contemporary environmental and political threats’ The New York TimesJack Smith’s life revolves around work, alcohol, painkillers, and pornography, and he sees no reason to change. But when he falls in love with the daughter of the leader of a new Californian religion known as Prescription for a Superior Existence, his humdrum life is changed forever.Abducted and enrolled at one of PASE’s spiritual training centres near San Francisco, Jack’s scepticism is challenged by a sense of community and purpose previously unknown to him. He discovers that he might not be average. He might be extraordinary. But nothing is as it seems, and the question of whether he and those around him are headed toward transcendence or annihilation soon takes on global significance.