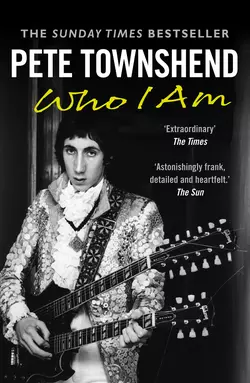

Pete Townshend: Who I Am

Pete Townshend

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1151.20 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: He is one of the greatest musical talents Britain has ever produced. But even as the principle songwriter and lead guitarist for The Who, it would be unjust to define Pete Townshend’s life simply through his achievements with bandmates Daltrey, Moon and Entwistle.Noting that he has sold over 100 million records over a fifty-year period goes some way to quantifying his accomplishments, but numbers only scratch the surface of his contribution to popular culture.An avid student of his profession, during his career he has been credited with the creation of the concept album, worked as a literary editor, developed scripts for television and the stage, and written songs that have defined a generation. The thinking man’s rock star with a dedication to his craft unlike any other in the business, he continues to inspire new generations of performers and writers with a continuing commitment to his art.Now, in one of the most eagerly awaited autobiographies of recent times, this icon tells about his incredible life and elaborates on the turbulences of time spent as one of the world’s most respected musicians – being in one of rock’s greatest ever bands, and wanting to give it all up.Incredibly, as a man who has achieved so much, this truly unique story of ambition, relentless perfectionism and rock and roll excess will be regarded as one of his greatest achievements.