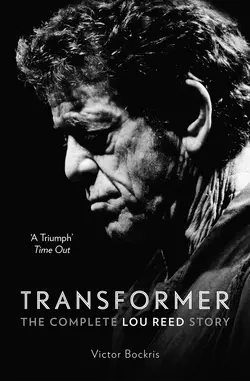

Transformer: The Complete Lou Reed Story

Victor Bockris

‘A triumph’ - Time OutTransformer is the only complete and comprehensive telling of the Lou Reed story.Legendary songwriter and guitarist Lou Reed passed away on the 27th October 2013, but his musical influence is assured. Now discover the true story of the Velvet Underground pioneer in this update of Bockris’s classic biography.Transformer: The Complete Lou Reed Story follows the great songwriter and singer through the series of transformations that define each period of his fifty year career. It opens with the teenage electroshock treatments that dominated his memories of childhood and never stops revealing layer after layer of this complex and often anguished artist and man. Transformer is based on Lou’s collaborations with the hardest and most romantic artists of his times, from John Cale, Andy Warhol, and Nico, through David Bowie, Robert Wilson, Laurie Anderson and the ghost of Edgar Alan Poe. Rippling underneath everything he did are Lou’s relationships with his various muses, from his college sweetheart to his three wives (and one drag queen).Leading Lou Reed biographer, Victor Bockris - who knew Lou throughout the Rachel Years, from Rock ‘n’ Roll Animal to the Bells - updates his original biography in the wake of Lou’s death. Through new interviews and photos, he reveals the many transformations of this larger-than-life character, including his final shift from Rock Monster to the Prince Charming he had always wanted to be in the twenty years he spent with the love of his life, Laurie Anderson . Except with Lou, you could never really know what might happen next…Including previously unseen photographs and contributions from Lou’s innermost circle and collaborators that include similarly esteemed artists such as Andy Warhol and David Bowie, Transformer is as captivating and vivid a read as befits an American master.

(#u38abb036-9b1c-55df-a553-8dc550b33194)

Copyright (#u38abb036-9b1c-55df-a553-8dc550b33194)

Harper

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

77–85 Fulham Palace Road

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Hutchinson 1994

This edition Harper 2014

© Victor Bockris 1994, 2014

A catalogue record of this book is

available from the British Library

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2014

Cover photograph © Simone Cecchetti/Corbis

While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material reproduced herein and secure permissions, the publishers would like to apologise for any omissions and will be pleased to incorporate missing acknowledgements in any future edition of this book.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/green)

Source ISBN: 9780007581894

Ebook Edition © October 2014 ISBN: 9780007581900

Version: 2014-10-05

Praise (#u38abb036-9b1c-55df-a553-8dc550b33194)

“Bockris’s new work is instantly recognizable as the heavyweight psychological powerplay Lou Reed’s legend deserves … Reed is effectively pinned like a butterfly”—Q

“Transformer depicts the singer’s life as a series of death-defying second acts”—New York Times Book Review

“A very readable portrait … Blending informed biographical narrative with abundant quotes and a dishy, conversational style, Bockris captures the many moods—and mood swings—of a true rock and roll chameleon”—Entertainment Weekly

“Transformer is an even more staggering brief than Wired (about John Belushi)”—Spin

“Bockris provides insight into the private life that led Reed to create many of rock’s memorable songs, including “Heroin” and “Walk on the Wild Side”—Publishers Weekly

“One of the funniest and most memorable time-lined rock documents around”—Philadelphia City Paper

Also by Victor Bockris (#u38abb036-9b1c-55df-a553-8dc550b33194)

Muhammad Ali in Fighter’s Heaven

Keith Richards: The Biography

Making Tracks: The Rise of Blondie (with Debbie Harry and Chris Stein)

Uptight: The Velvet Underground Story (with Gerard Malanga)

Warhol: The Biography

With William Burroughs: A Report from the Bunker

Patti Smith: A Biography

What’s Welsh for Zen: The Autobiography of John Cale (with John Cale)

Beat Punks

Rebel Heart: An American Rock ’n’ Roll Journey (with Bebe Buell)

The Burroughs–Warhol Affair

Burroughs Reloaded (photographs)

Dedication (#u38abb036-9b1c-55df-a553-8dc550b33194)

This book is dedcated to Barney Hoskyns, Gerard Malanga, Bob Gruen, and Legs McNeil

Contents

Cover (#u2215fd26-5ca5-55f4-84f1-4e4bc673fcb1)

Title Page (#u529431ee-4ddf-5c07-a9c7-dba3f76220da)

Copyright (#ulink_5ccb2ac4-c46e-5c9f-b4ea-6ff5fe8f63e6)

Praise (#ulink_ffbc3075-8b84-5269-981b-5f3af96f9409)

Also by Victor Bockris (#ulink_6da678b6-0536-5336-a5fd-f28399b9dadc)

Dedication (#ulink_e2b2f15e-4d31-5b10-832e-5945c226cc8a)

Acknowledgments (#ulink_b40e80f8-54be-56a6-9bd1-77dd6f97dc48)

Epigraph (#ulink_15ed0903-1d0e-5e16-83b7-5a10a59343c9)

One: Kill Your Son, 1959–60 (#ulink_5606e22e-d3eb-5006-a9b4-6c1f0b07b15a)

Two: Pushing the Edge, 1960–62 (#ulink_7cbf017d-51f2-5aaa-b64f-748082cbbb56)

Three: Shelley, If You Just Come Back, 1962–64 (#ulink_3a510f9a-d942-5492-adff-3d964ecf30d7)

Four: The Pickwick Period, 1964–65 (#ulink_80dc41f7-8888-5d87-874b-625bc9c52398)

Five: The Formation of the Velvet Underground, 1965 (#ulink_44fb207e-60e2-5752-baf2-d96a27ba397a)

Six: Fun at the Factory, 1966 (#ulink_762d8bbc-fcbd-5efa-bfa9-d89b5713df66)

Seven: Exit Warhol, 1966–67 (#litres_trial_promo)

Eight: Exit Cale, 1967–68 (#litres_trial_promo)

Nine: The Deformation of the Velvet Underground, 1968–70 (#litres_trial_promo)

Ten: Fallen Knight, 1970–71 (#litres_trial_promo)

Eleven: The Transformation from Freeport Lou to Frankenstein, 1971–73 (#litres_trial_promo)

Twelve: No Surface, No Depth, 1973–74 (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirteen: The Nervous Years, 1974–76 (#litres_trial_promo)

Fourteen: The Master of Psychopathic Insolence, 1977–78 (#litres_trial_promo)

Fifteen: Mister Reed, 1978–79 (#litres_trial_promo)

Sixteen: Ladybug, 1978–83 (#litres_trial_promo)

Seventeen: The New, Positive Lou (The Blue Lou), 1984–86 (#litres_trial_promo)

Eighteen: The Commercial, Political Lou, 1984–86 (#litres_trial_promo)

Nineteen: Imitation of Andy, 1987–89 (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty: Death Makes Three, 1990–93 (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-One: In Which Lou Reed Cannot Put On the Velvet Underwear, 1990–96 (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Two: The Transformation of Lou and Laurie, 1994–2000 (#litres_trial_promo)

Fast Forward: Val Kilmer’s Ranch, The Pecos, New Mexico, 2005 (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Three: Ecstasy, 1999–2001 (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Four: Lou Reed Rewrites Edgar Allan Poe, 2001–04 (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Five: Lou Reed Classics, 2006 (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Six: Lou Is Lulu, 2011–12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Seven: The Death of Lou Reed, 2013 (#litres_trial_promo)

Appendix A: Lou Reed and Laurie Anderson’s Inventories of Work (#litres_trial_promo)

Appendix B: Interviews with Lou Reed (#litres_trial_promo)

Source Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

List of Searchable Terms (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#u38abb036-9b1c-55df-a553-8dc550b33194)

Thanks for input and enlightenment to Andy Warhol, Lisa Krug, Andrew Wylie, Albert Goldman, Robert Dowling, Gerard Malanga, Syracuse University Rare Book Room, the staff of Creedmore Mental Hospital, Paul Sidey, lngrid von Essen, Dawn Fozard, Stellan Holm, Marianne Erdos, Barbara Wilkintson, Jessica Berens, Chantal Rosset, Elvira Peake, Anita Pallenberg, Marianne Faithfull, Allen Ginsberg, David Dalton, Miles, Jeff Goldberg, Ira Cohen, Rosemary Bailey, Phillip Booth, Allen Hymari, Andy Hyman, Richard Mishkin, Bob Quine, Raymond Foye, Diego Cortez, Clinton Heylin, Jan van Willegen, John Holmstrom, Legs McNeil, Bobbie Bristol, Ann Patty, Carol Wood, John Shebar, Charles Shaar Murray, Mick Farren, Michael Watts, Emie Thormahlen, Gisella Freisinger, William Burroughs, John Giomo, Stewart Meyer, Terrence Sellers, Chris Stein, Bob Gruen, David Bourdon, Jonathan Cott, Ed and Laura DeGrazia, Bobby Grossman, Art and Kym Garfunkel, Patti Giordano, Stephen Gaines, Lee Hill, Marcia Resnick, Michelle Loud, Terry Noel, Glenn O’Brien, Robert Palmer, Rosebud, Geraldine Smith, Walter Stedding, David Schmidlapp, Lynn Tillman, Hope Ruff, James Carpenter, Tei Carpenter, Toshiko Mori, Gus Van Sant, Mary Woronov, Matt Snow, Roger Ely, Paul Katz, Gayle Sherman, Cassie Jones, Dominick Anfuso, J. P. Jones, James Grauerholz, Terry and Gail Southern, Heiner Bastian, Danny Fields, Dr. J. Gross, Steve Bloom, Bridget Love, Mary Harron, Jeff Butler, Solveig Wilder, Rick Blume, Lenny Kaye, Tony Zanetta, Doug Yule, Tony Conrad, Richard Meltzer, Nick Kent, Richard Witts, Nick Tosches, Kurt Loder, Julie Burchill, and John Wilcock.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS TO THE 2014 EDITION

I am particularly grateful to the writers Barney Hoskyns, Nick Johnstone, and David Fricke, whose profiles of Lou Reed were always spectacular and insightful; Allan Jones for Uncut’s ultimate guide to Lou’s music and all his Lou Reed articles; Jann Wenner for Rolling Stone’s Lou Reed issue; Phil Alexander at Mojo, and all the rock writers who work so passionately to keep us in touch with the music; Roderick Romero, the creative force in his legendary trance rock band Sky Cries Mary and a giant in the tree-house world, who shared some visionary memories of his friendship with Lou; thanks also to Bob Gruen for his eyes and his sense of humor; David Schmidlapp, Barry Miles, and the staff of the beautiful Jane West Hotel.

One of the great ironies of Lou Reed’s life is that he would hardly have had a career if it weren’t for the outstanding writers who wrote glowingly about him in the face of his scorn. I have never understood why people in the rock world look upon biographies as attacks when they are the best free advertising a rock star could possibly get. All those people should thank the writers for taking the time to address their audiences intelligently, just as I am thanking every writer for everything I learned about Lou in his last truly great period. There is something deeply engaging in the Lou and Laurie story. Somebody should write a book about it.

Epigraph (#u38abb036-9b1c-55df-a553-8dc550b33194)

When I think of Lou, I remember what a romantic he was. And fun. And then when he had you hooked with that sweetness, he had to destroy you in order to survive. He couldn’t help himself, like any predator. He always warned his prey, partly as a challenge and partly to cover his ass for any later moral responsibility. What made the process interesting was the fact that it was an ongoing intellectual and artistic work—a performance piece.

An acquaintance

Chapter One

Kill Your Son (#u38abb036-9b1c-55df-a553-8dc550b33194)

ELECTROSHOCK: 1959–60

I don’t have a personality.

Lou Reed

Nineteen fifty-nine was a bad year for Lou, seventeen, who had been studying his bad-boy role ever since he’d worn a black armband to school when the No. 1 R&B singer Johnny Ace shot himself back in 1954. Now, five years later, the bad Lou grabbed the chance to drive everyone in his family crazy. Tyrannically presiding over their middle-class home, he slashed screeching chords on his electric guitar, practiced an effeminate way of walking, drew his sister aside in conspiratorial conferences, and threatened to throw the mother of all moodies if everyone didn’t pay complete attention to him.

That spring, Lou’s conservative parents, Sidney and Toby Reed, sent their son to a psychiatrist, requesting that he cure Lou of homosexual feelings and alarming mood swings. The doctor prescribed a then popular course of treatment recently undergone by, among many others, the British writer Malcolm Lowry and the famous American poet Delmore Schwartz. He explained that Lou would benefit from a series of visits to Creedmore State Psychiatric Hospital. There, he would be given an electroshock treatment three times a week for eight weeks. After that, he would need intensive postshock therapy for some time.

In 1959 you did not question your doctor. “His parents didn’t want to make him suffer,” explained a family friend. “They wanted him to be healthy. They were just trying to be parents, so they wanted him to behave.” The Reeds nervously accepted the diagnosis.

Creedmore State Psychiatric Hospital was located in a hideous stretch of Long Island wasteland. The large state-run facility was equipped to handle some six thousand patients. Its Building 60, a majestically spooky edifice that stood eighteen stories high and spanned some five hundred feet, loomed over the landscape like a monstrous pterodactyl. Hundreds of corridors led to padlocked wards, offices, and operating theaters, all painted a bland, spaced-out cream. Bars and wire mesh covered the windows inside and out. Among the creepiest of these cells was the Electra Shock Treatment Center.

Creedmore State Mental Hospital. (Victor Bockris)

Into this unit one early summer day walked the cocky, troubled Lou. He was escorted through a labyrinth of corridors, unaware, he later claimed, that his first psychiatric treatment session at the hospital would consist of volts of electricity pulsing through his brain. Each door he passed through would be unlocked by a guard, then locked again behind him. Finally he was locked into the electroshock unit and made to change into a scanty hospital robe. As he sat uncomfortably in the waiting room with a group of people who looked to him like vegetables, Lou caught his first glimpse of the operating room. A thick, milky white metal door studded with rivets swung open revealing an unconscious victim who looked dead. The body was wheeled out on a stretcher and into a recovery room by a stone-faced nurse. Lou suddenly found himself next in line for shock treatment.

He was wheeled into the small, bare operating room, furnished with a table next to a hunk of metal from which two thick wires dangled. He was strapped onto the table. Lou stared at the overhead fluorescent light bars as the sedative started to take effect. The nurse applied a salve to his temples and stuck a clamp into his mouth so that he would not swallow his tongue. Seconds later, conductors at the end of the thick wires were attached to his head. The last thing that filled his vision before he lapsed into unconsciousness was a blinding white light.

In the 1950s, the voltage administered to each patient was not adjusted, as it is today, for size or mental condition. Everybody got the same dose. Thus, the vulnerable seventeen-year-old received the same degree of electricity as would have been given to a heavyweight axe murderer. The current searing through Lou’s body altered the firing pattern of his central nervous system, producing a minor seizure, which, although horrid to watch, in fact caused no pain since he was unconscious. When Lou revived several minutes later, however, a deathly pallor clung to his mouth, he was spitting, and his eyes were tearing and red. Like a character in a story by one of his favorite writers, Edgar Allan Poe, the alarmed patient now found himself prostrate in a dim waiting room under the gaze of a stern nurse.

“Relax, please!” she instructed the terrified boy. “We’re only trying to help you. Will someone get another pillow and prop him up. One, two, three, four. Relax.” As his body stopped twitching, the clamp was removed, and Lou regained full consciousness. Over the next half hour, as he struggled to return, he was panicked to discover his memory had gone. According to experts, memory loss was an unfortunate side effect of shock therapy, although whatever brain changes occurred were considered reversible, and persisting brain damage was rare. As Reed left the hospital, he recalled, he thought that he had “become a vegetable.”

“You can’t read a book because you get to page seventeen and you have to go right back to page one again. Or if you put the book down for an hour and went back to pick up where you started, you didn’t remember the pages you read. You had to start all over. If you walked around the block, you forgot where you were.” For a man with plans to become, among other things, a writer, this was a terrible threat.

The aftereffects of shock therapy put Lou, as Ken Kesey wrote in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, “in that foggy, jumbled blur which is a whole lot like the ragged edge of sleep, the gray zone between light and dark, or between sleeping and waking or living and dying.” Lou’s nightmares were dominated by the sad, off-white color of hospitals. As he put it in a poem, “How does one fall asleep / When movies of the night await, / And me eternally done in.” Now he was afraid to go to sleep. Insomnia would become a lifelong habit.

Lou suffered through the eight weeks of shock treatments haunted by the fear that in an attempt to obliterate the abnormal from his personality, his parents had destroyed him. The death of the great jazz vocalist Billie Holiday in July, and the haunting refrain of Paul Anka’s No. 1 teen-angst ballad, “Lonely Boy,” heightened his sense of distance and loss.

According to Lou, the shock treatments helped eradicate any feeling of compassion he might have had and handed him a fragmented approach. “I think everybody has a number of personalities,” he told a friend, to whom he showed a small notebook in which he had written, “‘From Lou #3 to Lou #8—Hi!” You wake up in the morning and say, ‘Wonder which of them is around today?’ You find out which one and send him out. Fifteen minutes later, someone else shows up. That’s why if there’s no one left to talk to, I can always listen to a couple of them talking in my head. I can talk to myself.”

At the end of the eight-week treatment, Lou was put on strong tranquilizing medication. “I HATE PSYCHIATRISTS. I HATE PSYCHIATRISTS. I HATE PSYCHIATRISTS,” he would later write in one of his best poems, “People Must Have to Die for the Music.” But in his heart he felt betrayed. If his parents had really loved him, they would never have allowed the shock treatments.

***

Lewis Alan Reed was born on March 2, 1942, at Beth El Hospital in Brooklyn, New York. His father, Sidney George Reed, a diminutive, black-haired man who had changed his name from Rabinowitz, was a tax accountant. His mother, Toby Futterman Reed, seven years younger than her husband, a former beauty queen, was a housewife. Both parents were native New Yorkers who in a decade would move to the upper-middle class of Freeport, Long Island. Lewis developed into a small, thin child with kinky black hair, buck teeth, and a sensitive, nervous disposition. By that time, his mother, the model of a Jewish mother, had shaped her beauty-queen personality into an extremely nice, polite, formal persona that Lou later criticized in “Standing On Ceremony” (“a song I wrote for my mother”). She wanted her son to have the best opportunities in life and dreamed that one day he would become a doctor or a lawyer.

The house in Brooklyn where Lou was born. (Victor Bockris)

The emotional milieu that dominated Lewis’s life throughout his childhood was a kind of suffocating love. “Gentiles don’t understand about Jewish love,” wrote Albert Goldman in his biography of one of Lewis’s role models, Lenny Bruce. “They can’t grasp a positive, affectionate emotion that is so crossed with negative impulses, so qualified with antagonistic feelings that it teeters at every second on a fulcrum of ambivalence. Jewish love is love, all right, but it’s mingled with such a big slug of pity, cut with so much condescension, embittered with so much tacit disapproval, disapprobation, even disgust, that when you are the object of this love, you might as well be an object of hate. Jewish love made Kafka feel like a cockroach …”

In the opinion of one family friend, “Lou’s mother had the Jewish-mother syndrome with her first child. They overwatch their first child. The kid says watch me, watch me, watch me. You can’t watch them enough, and they’re never happy, because they’ve spent so much time being watched that’s what they expect. His mother was not off to work every morning, the mothers of this era were full-time mothers. Full-time watchers. They set up a scenario that could never be equaled in later life.”

When Lewis was five, the Reeds had a second child, Elizabeth, affectionately known as Bunny. While Lou doted on his little sister, her arrival was also cause for alarm. His mother’s love had become a trap built around emotional blackmail: first, since the mother’s happiness depends upon the son’s happiness, it becomes a responsibility for the son to be happy. Second, since the mother’s love is all-powerful, it is impossible for the son to return an equal amount of love, therefore he is perennially guilty. Then, with the arrival of the sister, the mother’s love can no longer be total. All three elements combine to put the son in an impossible-to-fulfill situation, making him feel impotent, confused, and angry. The trap is sealed by an inability to talk about such matters so that all the bitter hostility boiling below the surface is carefully contained until the son marries a woman who replaces his mother. Then it explodes in her face.

Goldman could have been describing Reed as much as Bruce when he concluded, “The sons develop into twisted personalities, loving where they should hate and hating where they should love. They attach themselves to women who hurt them and treat with contempt the women who offer them simple love. They often display great talents in their work, but as men they have curiously ineffective characters.”

The Reeds moved from an apartment in Brooklyn to their house in Freeport back in 1953—the year before rock began. Freeport, a town of just under thirty thousand inhabitants at the time, lay on the Atlantic coast, on the Freeport and Middle Bays—protected from the ocean by the thin expanse of Long Beach. The town, one of a thousand spanning the length of Long Island, was designed and operated around the requirements of middle-class families. Though just forty-five minutes from Manhattan by car or train, it could have been a lifetime away from Brooklyn, the city the family had just deserted. In fact, with well-funded parks, beaches, social centres, and schools, Freeport was suburban utopia. Thirty-five Oakfield Avenue, on the corner of Oakfield and Maxon, was a modern single-story house in a middle-class subsection of Freeport called the Village. Most of the houses in the neighborhood were built in colonial or ranch style, but Lewis’s parents owned a house that, in the 1950s, friends referred to as “the chicken coop” because of its modern, angular, single-floor design. Though squat and odd from the outside, it was beautifully laid out and comfortable, furnished in a 1950s modern style. It also had a two-car garage and surrounding lawn perfect for children to play on. In fact, the wide, quiet streets doubled as baseball diamonds and football fields when the local kids got together for a pickup game. Their neighborhood was for the most part upper-middle class and Jewish. The idea of urban Jewish ghettos had become as abhorrent to an increasingly powerful American Jewish population as it was to the continuing wave of European Jewish immigrants. Many Jewish families who had prospered in postwar New York had moved out of the city to similar suburban towns to get away from the last vestiges of the ghetto, and to create for themselves a middle-class life that would Americanize and integrate them. The resulting migration from New York to Long Island created a suburban middle class in which money was equated with stability, and wealth with status and power.

After graduating from Carolyn G. Atkinson Elementary and Freeport Junior High, in the fall of 1956, Lewis and his friends began attending Freeport High School (now replaced by a bunkerlike junior high). A large, stone structure, on the corner of Pine and South Grove, with a carved facade and expanse of lawn, the school resembled a medieval English boarding school like Eton or Rugby. It was a ten-minute walk from Oakfield and Maxon through the tree-lined neighborhood of Freeport Village and just over the busy Sunrise Highway. “I started out in the Brooklyn Public School System,” Lou said, “and have hated all forms of school and authority ever since.”

Lewis was surrounded by children who came from the same social and economic background. His closest friend, Allen Hyman, who used to eat at the Reeds’ all the time and lived only a block and a half away, remembered, “The inside of their house was fifties modern, living room and den. At least from sixth grade on my view of his upbringing was very, very suburban middle class.”

The area has a history of fostering comedians and a particular type of humor. Freeport in the twenties was a clam-digging town with an active Ku Klux Klan and German-American bund in nearby Lindenhurst. In the thirties and forties, it attracted a segment of the East Coast entertainment world, including many vaudeville talents. The vaudevillians brought with them not only their eccentric lifestyles and corny attitudes, but the town’s first blacks, who initially worked as their servants. By the time the Reeds got there, the show people were adding their own artistic bent to the town’s musical heritage. Their immediate neighbours included Leo Carrillo, who played Pancho on the popular TV show The Cisco Kid, as well as Xavier Cugat’s head marimba player and Lassie’s television mother, June Lockhart. Guylanders (Long Islanders) refuse to be impressed by celebrities, dignitaries, and the airs so dear to Manhattanites. “My main memory of Lou was that he had a tremendous sense of satire,” recalled high-school friend John Shebar. “He had a certain irreverence that was a little out of the ordinary. Mostly he would be making fun of the teacher or doing an impersonation of some ridiculous situation in school.”

Much Jewish humor took on a playfully cutting edge, intending to humble a victim in the eyes of God. Despite his modest temperament, Sidney Reed possessed a potent vein of Jewish humor, which he passed on to his son. As a child Lewis mastered the nuances of Yiddish humor, in which one is never allowed to laugh at a joke without being aware of the underlying sadness deriving from the evil inherent in human life. A family friend, recalling a visit to the Reed household, commented, “Lou’s father is a wonderful wit, very dry. He’s a match for Lou’s wit. That’s a Yiddish sense of humor, it’s very much a put-down humor. A Yiddish compliment is a smack, a backhand. It’s always got a little touch of mean. Like, you should never be too smart in front of God. Only God is perfect, and you should remember as pretty as you are that your head shouldn’t grow like an onion if you put it in the ground. You can either take it personally, like I think Lou unfortunately did, or not.”

During Lou’s childhood, Sidney Reed’s sense of humor had curious repercussions in the household. His well-aimed barbs often made his son feel put-down and his wife look stupid. Far from being resentful, Toby admired her husband for his obvious wit. Lou, however, was not so generous. “Lou’s mother thought she was dumb,” recalled a family friend. “I don’t think she was dumb. Lou thought she was dumb for thinking that his father was so clever. I think it was just jealousy. I think it was the boy who wanted all of his mother’s attention.” According to another friend, not only was Sidney Reed a wit, but he maintained a great rapport with Toby, who loved him dearly—much to the chagrin of the possessive, selfish, and often jealous Lewis. “I remember his mother was always amused by his father. His mother admires his father and thinks it’s too bad that Lou doesn’t see his father the way he is.”

One friend who accompanied Lou to school daily recalled that Toby Reed smothered her son with attention and concern. “I think his mother was fairly overbearing. Just in the way he talked about her. She was like a protective Jewish mother. She wanted him to get better grades and be a doctor.” Such attentions, of course, were fairly typical of full-time mothers in the family-oriented fifties. Allen Hyman never found her unusual. “I always thought Lewis’s mother was a very nice person,” he said. “She was very nice to me. I never viewed her as overbearing, but maybe he did. My experience of his parents was that they were very nice people. He might have perceived them as being different than they were. My mother and father knew his parents and my mother knew his mother. They were very involved parents. His mother was never anything but really nice. Whenever we went there, she was anxious to make sure we had food. His father was an accountant and seemed to be a particularly nice guy. But Lewis was always on the rebellious side, and I guess that the middle-class aspect of his life was something that he found disturbing. My experience of his relationship with his parents when we were growing up was that he was really close to them.

“His mother and father put up with a lot from him over the years, and they were always totally supportive. I got the impression that Mr. Reed was a shy man. He was certainly not Mr. Personality. When you went out with certain parents, it was fun and they were the life of the dinner and they bought you a nice meal, but when you went out with Sidney Reed, you paid. When you’re a kid, that’s unusual. The check would come and he’d say, ‘Now your share is …’ Which was weird. But that was his thing, he was an accountant.”

Lou’s father was very quiet; his mother had a lot more energy and a lot more personality. She was an attractive woman, always wore her hair short, had a lovely figure and dressed immaculately. “He’d always found the idea of copulation distasteful, especially when applied to his own origins,” Lou wrote in the first sentence of the first short story he ever published. The untitled one-page piece, signed Luis Reed, was featured in a magazine, Lonely Woman Quarterly, that Lou edited at Syracuse University in 1962. It hit on all the dysfunctional-family themes that would run through his life and work.

His quixotic/demonic relationship to sex was clearly intense. Lou either sat at the feet of his lovers or devised ingenious ways to crush their souls. The psychology of gender was everything. No one understood Lou’s ability to make those close to him feel terrible better than the special targets of his inner rage, his parents, Sidney and Toby. Lou dramatized what was in 1950s suburban America his father’s benevolent dominance into Machiavellian tyranny, and viewed his mother as the victim when this was not the case at all. Friends and family were shocked by Lou’s stories and songs about intra-family violence and incest, claiming that nothing could have been further from the truth. In the story, Lou had his mother say, “Daddy hurt Mommy last night,” and climaxed with a scene in which she seduced “Mommy’s little man.” Lou would later write in “How Do You Speak to an Angel” of the curse of a “harridan mother, a weak simpering father, filial love and incest.” The fact is that Sidney and Toby Reed adored and enjoyed each other. After twenty years of marriage, they were still crazy about each other. As for violence, the only thing that could possibly have angered Sidney Reed was his son’s meanness to his wife. However, these oedipal fantasies revealed a turbulent interior life and profound reaction to the love/hate workings of the family.

In his late thirties, Lou wrote a series of songs about his family. In one he said that he originally wanted to grow up like his “old man,” but got sick of his bullying and claimed that when his father beat his mother, it made him so angry he almost choked. The song climaxed with a scene in which his father told him to act like a man. He did not, he concluded in another song, want to grow up like his “old man.”

Reed’s moodiness was but one indication that he was developing a vivid interior world. “By junior year in high school, he was always experimenting with his writing,” Hyman reported. “He had notebooks filled with poems and short stories, and they were always on the dark side.” Reed and his friends were also drawn to athletics. Freeport High was a football school. Under the superlative coaching of Bill Ashley, the Freeport High Red Devils were the pride of the town. Lou would claim in Coney Island Baby that he wanted to play football for the coach, “the straightest dude I ever knew.” But he had neither the size nor the athletic ability and never even tried out. Instead, during his junior year Lou joined the varsity track team. He was a good runner and was strong enough to become a pole-vaulter. (He would later comment on Take No Prisoners that he could only vault six feet eight inches—“a pathetic show.”) Although he preferred individual events to team sports, he was known around Freeport as a very good basketball player. “Lou Reed was not only funny but he was a good athlete,” recalled Hyman. “He was always kind of thin and lanky. There was a park right near our house and we used to go down and play basketball. He was very competitive and driven in most things he did. He would like to do something that didn’t involve a team or require anybody else. And he was exceptionally moody all the time.”

Allen’s brother Andy recalled that it was typical of Lou to maintain a number of mutually exclusive friendships, which served different purposes. Allen was Lewis’s conservative friend, while his friend and neighbor Eddie allowed him to exercise quite a different aspect of his personality. “Eddie was a real wacko,” commented another high-school friend, Carol Wood, “and he only lived about four houses away from Lou. He had all these weird ideas about outer-space Martians landing and this and that. During that time there was also a group in town that was robbing houses. They were called the Malefactors. It turned out that Eddie was one of them.”

“Eddie was friendly with Lou and with me, but Eddie was a lunatic,” agreed Allen Hyman. “He was the first certifiable person I have ever known. He was one of those kids who your mother would never want or allow you to hang out with because he was always getting into trouble. He had a BB gun and he would sit up in his attic and shoot people walking down the street. Lou loved him because he was as outrageous as he was, maybe more. He used to get arrested, he was insane.”

“There was a desire on Lewis’s part—of course I didn’t know this at the time—to be accepted by the regular kinds of guys, and on the other hand he was very attracted to the degenerates,” Andy recalled. “Eddie was kind of a crazy guy who was into petty theft, smoking dope at a very early age, and into all kinds of strange stuff with girls. And Lewis was into all that kind of stuff with Eddie while he was involved with my brother in another scene.” Having managed to convince his parents to buy him a motorcycle, Lou would ride around the streets of Freeport in imitation of Marlon Brando.

Where Lou spent his troubled teen years in Freeport. (Victor Bockris)

According to his own testimony, what made Lewis different from the all-American boys in Freeport was the fact, discovered at the age of thirteen, that he was homosexual. As he explained in a 1979 interview, the recognition of his attraction to his own sex came early, as did attempts at subterfuge: “I resent it. It was a very big drag. From age thirteen on I could have been having a ball and not even thought about this shit. What a waste of time. If the forbidden thing is love, then you spend most of your time playing with hate. Who needs that? I feel I was gypped.”

“There was no indication of homosexuality except in his writing,” said Hyman. “Towards our senior year some of his stories and poems were starting to focus on the gay world. Sort of a fascination with the gay world, there was a lot of that imagery in his poems. And I just thought of it as his bizarre side. I would say to him, ‘What is this about, why are you writing about this?’ He would say, ‘It’s interesting. I find it interesting.’”

“I always thought that the one way kids had of getting back at their parents was to do this gender business,” recalled Lou. “It was only kids trying to be outrageous. That’s a lot of what rock and roll is about to some people: listening to something your parents don’t like, dressing the way your parents won’t like.”

Throughout his adolescence, Lou was saved by his real passion, rock and roll. Lou had fallen for the new R&B sounds in 1954, when he was twelve. Almost instantly, he had started composing songs of his own. Like his fellow teenager Paul Simon, who grew up in nearby Queens, Lou formed a band and put out a single of his own composition at the age of fifteen, appropriately called “So Blue.” To Lou’s parents, these early signposts of a musical career were ominous. Their dreams of having their only son become a doctor or, like his father, an accountant were vanishing in the haze of pounding music and tempestuous moods. Since puberty Lou had honed a sharp edge, wounding his parents with both public and private insults. In his teens, Lou led Mr. and Mrs. Reed to believe he would become both a rock-and-roll musician and a homosexual—the stuff of nightmares for suburban parents of the 1950s. Actively dating girls at the time, and giving his friends every impression of being heterosexual, Lou enjoyed the shock and worry that gripped his parents at the thought of having a homosexual son. “His mother was very upset,” recalled a friend. “She couldn’t understand why he hated them so much, where that anger came from. At first, they had no malice, they tried to understand. But they got fed up with him.”

Reed playing in one of his highschool bands, the C.H.D. or, backwards, Dry Hump Club.

Throughout his teens, Lou would try anything to break the tedium of life in Freeport, especially if it was considered outside conventional norms. Lou found other characters who were also desperate to elude boredom. One such moment came about indirectly through his interest in music. Every evening, the better part of the high-school population of Freeport and its neighboring towns would tune into WGBB radio to hear the latest sounds, make requests, and dedicate songs. Often the volume of telephone calls to the station would be so great that the wires would get crossed, creating a teenage party-line over which friendships developed. On one occasion, Lou became friendly with a caller. “There was this girl who lived in Merrick,” explained Allen Hyman. “She was fairly advanced for her time, and Lou ended up going out on a date with her. He came back from the date, and he called me up and he said, ‘I’ve just had the most amazing experience. I took this girl to the Valley Stream drive-in and she took out a reefer.’ And I said, ‘Is she addicted to marijuana?’ Because in those days we thought if you smoked marijuana, you were an addict. He said, ‘No, it was cool. I smoked this reefer, it was really great.’”

The decades in which Lewis grew up, the fifties and early sixties, were characterized by middle-class unconsciousness and safety. Much like in the TV series Happy Days, most teenagers were more interested in having a good time than experiencing a wider worldview. “There was not a tremendous amount of consciousness about what was happening on the planet,” commented Allen Hyman. “But Lou was always interested in questioning authority, being a little outrageous, and he was certainly a person who would be characterized as mildly eccentric.”

Lou’s eccentric rebellious side found a lot to gripe about within the conservative, white confines of his neighborhood. Hyman remembered that, though outwardly polite, Lou harbored a hatred of his environment that was manifested in an ill will for Allen’s right-wing father. “The reason he disliked my father so much was because he always viewed him as the consummate Republican lawyer. He was very aware early on of political differences in people. We lived in an area that was Republican and conservative, and he always rebelled against that. I couldn’t understand why that upset him so much. But he was always very respectful to my parents.”

Mr. Reed, along with Mr. Hyman, discouraged musical careers for their sons. “He thought there were bad people involved, which there were,” recalled Lou. However, as Richard Aquila wrote in That Old Time Rock and Roll, “adult fear of rock and roll probably says more about the paranoia and insecurity of American society in the 1950s and early 1960s than it does about rock and roll. The same adults who feared foreigners because of the expanding Cold War, and who saw the Rosenbergs and Alger Hiss as evidence of internal subversion, often viewed rock and roll as a foreign music with its own sinister potential for corrupting American society.”

Lewis enjoyed the comforts of his middle-class upbringing, but acted as if he were estranged from the dominant values of suburban American life. Lou would rewrite his childhood repeatedly in an attempt to define himself. Some of his most famous songs, written in reaction to his parents’ values, have a stark, despairing tone that spoke for millions of children who grew up in the stunned and silent fifties of America’s postwar affluence. One friend put her finger on the pulse of the problem when she pointed out that Lou had an extreme case of shpilkes—a Yiddish term that perfectly sums up his contradictory nature: “A person with shpilkes has to scratch not only his own itch, he can’t leave any situation alone or any scab unpicked. If the teenage Lewis had come into your home, you would have said, ‘My God, he’s got shpilkes!’ Because he’s cute and he’s warm and he’s lovable, but get him out of here because he’s knocking the shit out of everything and I don’t dare turn my back on him. He’s causing trouble, he’s aggravating me, he’s a pain in the ass!” According to Lou, he never felt good about his parents. “I went to great lengths to escape the whole thing,” he said when he was forty years old. “I couldn’t relate to it then and I can’t now.” As he saw himself in one of his favorite poems by Delmore Schwartz: “… he sat there / Upon the windowseat in his tenth year / Sad separate and desperate all afternoon, / Alone, with loaded eyes …”

Another charge Lou would lob at his unprotected parents was that they were filthy rich. This was, however, purely an invention Lou used to dramatize his situation. During Lou’s childhood his father made a modest salary by American standards. The kitchen-table family possessed a single automobile and lived in a simply though tastefully furnished house with no vestiges of luxury or loosely spent funds. Indeed, by the end of the 1950s, what with the shock treatments, Lou’s college tuition, and their daughter Elizabeth’s coming into her teens, the Reeds were stretched about as far as they could reach.

***

The year of his electroshock treatments, 1959, through the summer of 1960 was a lost time for Lou. From then on, the central theme of his life became a struggle to express himself and get what he wanted. The first step was to remove himself from the control of his family, which he now saw as an agent of punishment and confinement. “I came from this small town out on Long Island,” he stated. “Nowhere. I mean nowhere. The most boring place on earth. The only good thing about it was you knew you were going to get out of there.” In August he registered and published a song called “You’ll Never, Never Love Me.” A gut resentment of his parents was blatantly expressed in another song, “Kill Your Sons.” The music, he later said, gave him back his heartbeat so he could dream again. “The music is all,” he wrote in a wonderful piece of prose called “From the Bandstand.” “People should die for it. People are dying for everything else, so why not for the music. It saves more lives.”

Chapter Two

Pushing the Edge (#u38abb036-9b1c-55df-a553-8dc550b33194)

SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY: 1960–62

Lou liked to play with people, tease them and push them to an edge. But if you crossed a certain line with Lou, he’d cut you right out of his life.

Allen Hyman

In order to continue their friendship, Lou and Allen Hyman had conspired to attend the same university. “In my senior year in high school Lou and I and his father drove up to Syracuse for an interview,” recalled Allen. “We didn’t speak to his father much, he was quiet. Quiet in the sense of being formal—Mr. Reed. We stayed at the Hotel Syracuse, which was then a real old hotel. There were also a bunch of other kids who were up for that with their parents. Would-be applicants to Syracuse. Lou’s father took one room and Lou and I took another. We met a bunch of kids in the hall that were going to Syracuse and we had this all-night party with these girls we met. We thought this was going to be a gas, this is terrific. The following day we both knew people who were going to Syracuse at the time who were in fraternities, and the campus was so nice, I think it was the summer, it was warm at the time, it looked so nice.”

The two boys made an agreement that if they were both accepted, they would matriculate at Syracuse. “We both got in,” said Hyman. “And the minute I got my acceptance I let them know I was going to go and I called Lou very excited and said, “I got my acceptance to Syracuse, did you?” And he said, ‘Yes.’ So I said, ‘Are you going?’ and he said, ‘No.’ And I said, ‘What do you mean, no? I thought we were going, we had an agreement.’ He said, ‘I got accepted to NYU and that’s where I’m going.’ I said, ‘Why would you want to do that, we had such a good time up there, we liked the place, I told them I was going, I thought you were going.’ He said, ‘No, I got accepted at NYU uptown and I’m going.’”

Lewis Reed, 17, 1959. ‘I don’t have a personality.’

In the fall of 1959, Lou headed off to college. Located in New York City, New York University seemed like a smart choice for a man who loved nothing more than listening to jazz at the Five Spot, the Vanguard, and other Greenwich Village clubs. But the Village was not the NYU campus Lou chose. Almost incomprehensibly, he signed up for the school’s branch located way uptown in the Bronx. NYU uptown provided Reed with neither the opportunities nor the support that he needed. Instead, Lou was left floundering in a strange and hostile environment. One of his few pleasures came from visiting the mecca of modern jazz, the Five Spot, regularly, but he didn’t always have the money to get in and often stood outside listening to Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane, and Ornette Coleman as the music drifted out to the street.

However, Lou’s main concern was not college. The Bronx campus was convenient to the Payne Whitney psychiatric clinic on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, where he was undergoing an intensive course of postshock treatments. According to Hyman, who talked to him on the phone at least once a week through the semester, Lou was having a very, very bad time. “He was in therapy three or four times a week,” Hyman recalled. “He hated NYU. He really hated it. He was going through a very difficult time and he was taking medication. He was having a lot of difficulty dealing with college and day-to-day business. He was a mess. He was going through a lot of very, very bad emotional stuff at the time and he probably had something very close to a minor breakdown.”

After two semesters, in the spring of 1960, having completed the Payne Whitney sessions although still on tranquilizers, Lou couldn’t take the NYU scene anymore.

One of the few people who encouraged Lou during his yearlong depression was his stalwart childhood friend, Allen Hyman, who now urged him to get away from his parents. Allen encouraged Lou to join him at Syracuse—a large, prestigious, private university, hundreds of miles from Freeport. In the fall of 1960, shaking off the shadows of Creedmore and the medication of Payne Whitney, Reed took Hyman’s advice and enrolled at Syracuse.

***

The coeducational university, attended by some nineteen thousand sciences and humanities students, had been established in 1870. It was located on a 640-acre campus atop a hill, in the middle of the city. Its $800 per term tuition was relatively high for a private university. Most of the students lived in sororities and fraternities and were enjoying one last four-year party before putting aside childish notions for the economic responsibilities of adulthood. There was, among the student population, a large and wealthy Jewish contingent, generally straight-arrow fraternity men and sorority women bound for careers in medicine and law. There was a small margin of artists, writers, and musicians with whom Lou would throw in his lot, enjoying, for the first time in his life, a niche in which he could find a degree of comfort. Among many other talented and successful people, the artist Jim Dine, the fashion designer Betsey Johnson, and the film producer Peter Guber all graduated in Reed’s class of 1964.

The Syracuse campus looked like the perfect set for a horror movie about college life in the early 1960s. Its buildings resembled Gothic mansions from a screenwriter’s imagination. Indeed, the scriptwriter of The Addams Family TV show of the 1960s, who attended the university at the same time as Lou, used the classically Gothic Hall of Languages as the basis for the Addams Family mansion. The surrounding four-block-square area of wooden Victorian houses, Depression-era restaurants, stores, and bars completed the college landscape. A pervasive ocher-gray paint lent a somber air to the seedy wooden houses tucked away in side streets covered, most of the time, with snow, wet leaves, or rain. The atmosphere was likely to elicit either poetic contemplation or depressive madness. It provided a perfect backdrop for the beatnik lifestyle.

The surrounding city of Syracuse presented no less smashed a landscape. The manufacturing town got dumped with snow seven months of the year, and heavy bouts of rain the rest of the time. Only during the summer, when most of the students had scattered to their homes on Long Island or New Jersey, did the city receive warmth and sunshine. A thriving industrial metropolis popularly known as the Salt City, also specializing in metals and electrical machinery, it was two hundred miles northwest of Freeport, forty miles south of Lake Ontario on the Canadian border, and five miles southwest of Oneida Lake. Syracuse was aggressively conservative and religious, but at the time of Reed’s arrival it was fast turning into the academic hub of the Empire State. The city proudly supported its prestigious university, whose popular football team, the Orangemen, was undefeated during Lou’s four years, and its residents turned out in great numbers for athletic events. Despite high academic standards, Syracuse was still primarily seen as a football school. “Where the vale of Onondaga / Meets the eastern sky / Proudly stands our Alma Mater / On her hilltop high” ran the opening verse of the school song, a ditty Lewis, as many of his friends called him, would not forget.

As a freshman, Lou was assigned to the far southwestern corner of the North Campus in Sadler Hall, a plain, boxlike dormitory resembling a prison. However, much of his time was spent in the splendid, gray-stone Hall of Languages, which overlooked University Avenue and University Place at the north end of campus and housed the English, history, and philosophy departments.

Syracuse University had excellent faculty and academic courses. Though Lou may have sleepwalked through much of the curriculum, he threw himself into the music, philosophy, and literature studies in which he excelled. In music appreciation, theory, and composition classes, Lou soaked up everything, even opera. First, Lou tried his hand at journalism, but he dropped that after a week when the teacher told him his opinions were irrelevant. However, Lou quickly immersed himself in philosophy. He devoured the existentialists, obsessed over the tortuous dialectics of Hegel, and embraced the Fear and Trembling of Kierkegaard. “I was very into Hegel, Sartre, Kierkegaard,” Reed recalled. “After you finish reading Kierkegaard, you feel like something horrible has happened to you—fear and nothing. That’s where I was coming from.” He also loved Krafft-Ebing and the writing of the beat generation, particularly Kerouac, Burroughs, and Ginsberg. To complete his freshman image, he took imagistic inspiration from the brash, tortured figures of James Dean, Marlon Brando, and, most of all, Lenny Bruce.

To his advantage, Reed already had the perfect agent to introduce him to the university, the smooth operator and prince of good times Allen Hyman, now entering his sophomore year. Another pampered suburban kid who drove both a Cadillac and Jaguar, Allen was generous, full of good humor, and sharp-witted. Furthermore, he genuinely appreciated Lou and was willing to put up with a lot of flak to remain his friend. Hyman was well connected with the straight fraternity set and eager to introduce Lewis to his world.

However, a highly uncomfortable introduction came about when Allen tried to get Lou to rush his fraternity, Sigma Alpha Mu (aka the Sammies). “Hazing was a really horrendous experience and most people were very intimidated by it,” recalled Hyman. Inductees were forced to drink themselves into oblivion and were often humiliated physically, sexually, and mentally by the fraternity brothers. When Allen told Lou stories about what he went through to join a fraternity, Lou shot him a hard look, snapping, “What are you into—masochism?”

“He had said that he didn’t want anything to do with it and that it was fascistic and disgusting,” Hyman recalled, “and he couldn’t believe anybody would be willing to go through hazing without killing the person who was hazing them.” However, typically perversely, Reed agreed to attend a rush session.

From the outset it was clear that he intended to make a strong impression. Reed came to the socializer in a suit three sizes too small and covered in dirt. It was a radical departure from the blue blazer, smart tie, and neatly combed hair of the other rushees. Allen immediately realized how much Lou was getting off on being outrageous. When one of the brothers criticized Lou’s appearance, Reed riposted, “Fuck you!” and his fraternity career came to an abrupt end. Hyman was asked to escort his friend out immediately. Walking Lou back to his dorm, a chagrined Allen hung his head regretfully, but Lou, far from being despondent, appeared exhilarated by the event. “I guess this isn’t for you,” Allen said.

“Yeah, that’s right,” Lou replied. “I told you I wouldn’t get along with those assholes. How can you live there?”

Another freshman trial that Lou failed was with the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps. As part of his freshman course requirements, he had to choose between physical education and ROTC. (In those days it was common to join ROTC in order to be able to go into the army as an officer and a gentleman.) Claiming that he would surely break his neck in phys ed or else kill somebody in ROTC, Lou attempted to evade either requirement, but in the end grudgingly signed up for the latter. ROTC consisted of two classes a week about how to be a soldier and possibly a leader. However, Lou’s military experience was almost a short-lived as his fraternity stint. Just weeks into the semester, when he flatly refused a direct order from his officer, he was unceremoniously booted out.

But Reed managed to make an impact on his freshman year with his very own radio show. Employing a considerable boyish charm to overcome the severe doubts of program director Katharine Griffin, during his first semester Lou hustled his way onto the Syracuse University radio station, WAER FM, with a jazz program called Excursions on a Wobbly Rail (named for a wicked Cecil Taylor piece that was used as his introductory theme). The classical, conservative station, Radio House, was situated in a World War II Quonset hut tucked away behind Carnegie Library. Freezing his balls off through many icy Syracuse evenings, hunched over his ancient machinery like some WWII underground resistance fighter for two hours, three nights a week, Lou blasted a mélange of his favorite sounds by the avant-garde leaders of the Free Jazz movement Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry, the doo-wopping Dion, and the sexually charged Hank Ballard, James Brown and the Marvelettes. The mixture presented the essence of Lou Reed. “I was a very big fan of Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, Archie Shepp,” he recalled. “Then James Brown, the doo-wop groups, and rockabilly. Put it all together and you end up with me.”

Unfortunately, the Reedian canon was not appreciated by the station’s staff, and numerous faculty members, including the dean of men, lodged complaints about the—to them—hideous, unintelligible cacophony that was Reed’s program. And the authorities’ reaction was not Lou’s only problem. Disguising his voice, Allen Hyman would often call Lou at the station and harass him with ridiculous requests. On one occasion, “I asked him to play something he hated and I knew he would never play,” Allen recalled. “He said, ‘No, I’m not going to play that, forget it.’ So I said, ‘Listen, if you don’t play this, I’m gonna fucking have you killed. I’ll wait for you myself and I’m gonna kill you!’ And, thinking it was some lunatic, Lou got scared. Then I called him back and told him it was me and he screamed at me, saying that if I ever did that again he’d never speak to me.”

As it turned out, Allen’s pranks didn’t last long enough to lose him Lou’s friendship because before long Griffin, ever vigilant in her duties as WAER’s program director, concluded that “Excursions on a Wobbly Rail was a really weird jazz show that sounded like some new kind of noise. It was just too weird and cutting edge.” Before the end of the semester, she unceremoniously dumped it from the air, causing Lou considerable anguish.

In retrospect, Griffin and her contemporaries realized that Reed was simply ahead of his time. “Most of us who were in power on campus were children of the fifties,” she explained. “Kids in those days wore chinos and madras shirts, a clean-cut Kingston Trio kind of thing. Lou looked more like what a rock person from later in the sixties would look like. Lou was presaging the sixties and seventies and we just weren’t ready for it. He was right on the cusp of two generations. A little too far ahead to be admired in the fifties.”

During his first year at Syracuse, the scholarly Griffin concluded, “It was just Lou versus everybody else.”

Lou quickly defined himself as an oddball loner. Eschewing all organizations, he was creating an image that would in time become widely acknowledged as the essence of the hip New York underground man. Lou was a year older than most freshmen and fully grown. Measuring five feet eight inches (although he claimed to be five feet ten) he was a little chubby and some way yet from the Lou Reed of “Heroin.” He wore loafers, jeans, and T-shirts, tending, if anything, to be a little sloppier than the majority of men at school, who wore the fraternity uniform of jacket and tie. His hair was a trifle longer than theirs. Otherwise, he would not have been noticed in a crowd. His looks tended toward the cute, boyish, curly haired, shy, gum-chewing. He had a small scar under his right eye. His most unusual feature was his fingers. Short and strong, they broadened into stubby, almost blocklike fingertips, making them perfect tools for the guitar.

Lou had already formed his ambition to be a rock-and-roller and a writer. The university’s rich music scene consisted of an eclectic mix of talents like Garland Jeffreys, a future singer-songwriter and Reed acolyte two years younger than Lou; Nelson Slater, for whom Lou would later produce an album; Felix Cavaliere, the future leader of the Young Rascals; Mike Esposito, who would form the Blues Magoos and the Blues Project; and Peter Stampfel, an early member of the Holy Modal Rounders, who would become a pioneer of folk rock. While colleges in New York and Boston produced folksingers in the style of Bob Dylan, Syracuse created a bunch of proto-punk rockers.

Most importantly for Lou musically, it was at Syracuse he met fellow guitarist Sterling Morrison, a resident of Bayport, Long Island, who had a similar background. Just after Lou got kicked out of ROTC, Sterling, who was never actually enrolled at Syracuse but spent a lot of time there hanging out and sitting in on some classes, was visiting another student, Jim Tucker, who occupied the room below Lou’s. Gazing out Tucker’s window at the ROTC cadets marching up and down the quad one afternoon, Morrison suddenly heard “earsplitting bagpipe music” wail from someone’s hi-fi. After that, the same person “cranked up his guitar and gave a few shrieking blasts on that.” Excited, Morrison realized, “Oh, there’s a guitar player upstairs,” and prevailed on Tucker for an introduction.

When they met at 3 a.m. the following morning, Lou and Sterling discovered they shared a love for black music and rock and roll. They also loved Ike and Tina Turner. “Nobody even knew who they were then,” Morrison recalled. “Syracuse was very, very straight. There was a one percent lunatic fringe.”

Luckily, the drama, poetry, art, and literary scenes were just as alive as the music scene for that one percent fringe. Soon Lou was spending the majority of his time playing guitar, reading and writing, or engaging in long rap sessions with like-minded students. Many of Lou’s conversations about philosophy and literature took place in the bars and coffee shops he and his friends began to call their own. Each restaurant had its social affiliations. Lou’s crowd set up camp at the Savoy Coffee shop run by a lovable old character, Gus Joseph, who could have walked right out of a Happy Days TV episode. At night, they drank at the Orange Bar, frequented predominantly by intellectual students. According to Lou, he took two steps out of school and there was the bar. “It was the world of Kant and Kierkegaard and metaphysical polemics that lasted well into the night,” he remembered. “I often went to drink alone to that week’s lost everything.” He had become accustomed to taking prescription drugs and smoking pot, but Lou was not yet a heavy user of illegal substances. At the most he might have a Scotch and a beer.

At Syracuse, Lou presented himself as a tortured, introspective, romantic poet. Following the dictate that the first step to becoming a poet is to look and act like one, Lou liked, for example, to give the impression that he was unwashed, but that wasn’t true. According to one friend, “He wasn’t about to go out unless he took a shower first.” As far as his costume was concerned, he was still stuck somewhere between the suburban teenager in loafers and button-down shirts and the rumpled dungarees and work shirts of the Kerouac rebel. Observers remembered him as more chubby and cherubic than thin and ascetic. In fact, he didn’t dress unusually at all. If anything, he dressed poorly, wearing the same pair of dirty jeans for months. As for his demeanor, Lou copped the uptight approach of the young Rimbaud. He was just beginning to swing with the legend of his electroshock treatments, turtleneck sweaters, and the whole James Dean inspired “I’ve suffered so much everything looks upside down” routine.

According to one student who occasionally jammed with him, “Part of his aura was that he was a psychologically troubled person who in his youth had had electroshock treatments which clearly had an effect on him. He used that as part of his persona. Where the reality and the fantasy of what he was crossed, who knew.” For a sarcastic kid who had grown up with buck teeth, braces, and a nerd’s wardrobe, Lou wasn’t doing badly turning himself into the image of a totally perverse psycho. However, whatever he did with his wardrobe and his attitude to make himself hip, there was one nightmarish detail about his looks that seemed always to overwhelm him—his hair. His frizzy helmet had plagued him since he’d started looking into the mirror with intense interest in his twelfth year. What stared back at him throughout his adolescence was a Jewish version of Alfred E. Neumann.

Since America had been a largely anti-Semitic nation, the Jewish “Afro” was seen as geekishly ethnic. In the early sixties, Bob Dylan would single-handedly change the image of what a hip young boy could look like. Though the film industry and media characters like Allen Ginsberg had begun to turn the whole Jewish male persona into something ultra-chic, nobody came close to having the pervasive influence of Bob Dylan. As Ginsberg explained to his biographer Barry Miles, when Dylan appeared, particularly in his 1965 Bringing It All Back Home incarnation, he made the hooked nose and frizzy hair the very emblem of the hip, intellectual avant-garde. By the time Lou got to college, however, and started to resculpt himself into the Lou Reed who would emerge in 1966 as the closest competition to Dylan for the hippest rock star in the world, he was ready to do something about his hair. At Syracuse he discovered a hair-treatment place in the black neighborhood and on several occasions had his hair straightened.

Just like his British counterparts Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones or John Lennon of the Beatles, Lou rejected the lifestyle that came before the bomb and was remaking himself out of a combination of his favorite stars. Such self-creation was not difficult for Lou, who often claimed he had as many as eight personalities. He now clothed these personalities in the costumes and attitudes of a cast of media characters who were as important to his image as the first creative friends he would hook up with at Syracuse.

First among them was Lenny Bruce. Though damned by his legal problems to a horrible fate, Bruce was at the apogee of his career. In the eyes of the public he was the hippest, fastest-talking American poet and philosopher around. Bruce spiked his act—a kind of Will Rogers on fast-forward—by injections of pure methamphetamine hydrochloride, which would in time become Lou’s own drug of choice. Many of Reed’s mannerisms, his hand gestures, the way he answered the phone as if he was asleep, the rhythm of his speech, came directly from Bruce.

As for the rest of Lou’s media idols, you only have to look at a panel of head shots of the stars of the era to see what Lou would take in time from Frank Sinatra, Jerry Lewis in The Bellboy, Montgomery Clift, and William Burroughs, to name but a few of the more obvious ones. In fact, one of Lou’s most attractive characteristics was the way he appreciated and celebrated his heroes. He was always trying to get Hyman, for example, a straight law student whose path would lead in a direction diametrically opposite to Lou’s, to read Kerouac and then rap with him about it. Lou loved turning people on to the new sounds, the new scenes, and the new people.

A lot of the artistic kids who went to Syracuse look back upon it with disdain as a football school dominated by the “fucking” Orangemen. In fact, in that watershed period between the end of McCarthyism and the death of Kennedy, a new permissiveness swept through colleges across the country. Syracuse contained and nurtured a lot of different environments. Certainly the fraternity environment still dominated the American campus, and the majority of male and female students still aligned themselves with a fraternity or sorority in sheeplike fashion. There was, however, a vital cultural split between the Jewish and the non-Jewish fraternities. The Jewish fraternities were for the most part hipper, more receptive to the new culture and more open to alternative ways of living. Despite completely rejecting Sigma Alpha Mu and attaching himself primarily to the arty intellectual crowd, some of whom had apartments off campus, Lou maintained a loyal friendship with Hyman and was, in fact, adopted as something of a mascot by the Sammies as their resident oddball. They weren’t about to miss out completely on a character who had already, in the first half of his freshman year, carved out an image for himself as tempestuous and evil. In fact, Jewish fraternities in colleges across America would provide some of the most receptive of Lou Reed’s audiences throughout his career.

The rules that governed a freshman’s life at Syracuse were greatly to the advantage of the male students. Whereas the girls in the dorm atop Mount Olympus were locked in at 9 p.m., and any girl who dared break curfew was subject to expulsion, the boys, who had no curfew, were able to use the night to live a whole other life, exploring the town, drinking in the Orange or in frat houses and getting up to all sorts of mischief. Naturally Lou, who had developed the habit of staying up most of the night reading, writing, and playing music, lost no time exploring his new home. He quickly discovered the neighboring black ghetto where at least one club, the 800, presented funky jazz and R&B as well as a whole culture, centered around drugs, music, and danger, that appealed to the explorer of the dark side in Reed.

Lou’s first college girlfriend was Judy Abdullah, and he called her The Arab. It may be that she was of more interest to him as an exotic object than as a person. Judy revealed an interesting quirk in Lou’s sexuality. He was turned on by big women. Judy Abdullah was twice his size. She was a sensual woman and they apparently had a good time in bed, but at least one acquaintance added a shade to Reed’s personality profile when she pointed out that his attraction to big women offered both a challenge and an escape route. Lou could take the attitude that he had no responsibility to be serious about her or even try to satisfy her.

The relationship petered out before the end of the year. Lou, who persisted in not wasting time with dates and always coming on obnoxiously, was mean to Judy, and when they broke up, she was pissed off at him for good reason. Still, they remained acquaintances and Lou saw her occasionally throughout his college years.

By the end of his first year at Syracuse, according to one of the Sammies, “Lou’s uniqueness and stubbornness made him different from anyone I had ever known. He marched to his own drum. He was for doing things for people, but his way. He would never dress or act in a way so that people would accept him. Lou had an unbelievably wry, caustic sense of humor and loved funny things. He played off people. He would often act in a confrontational manner. He wanted to be different. Lou was a funny guy in an extremely dry, witty sense. Certainly not the type of comedian that would make you laugh at him. He wasn’t making fun of things but seeing the humor in things—the banal and the normal. There was an undercurrent of saneness in everything he did. He was screwed up, but that was schizophrenia too.”

***

What Lou Reed needed most was to find a coconspirator, an equal off whom he could bounce his ideas and behavior and receive inspiration in return. Almost miraculously, he found such a person in what would become the second golden period of his life (the first being his discovery of rock and roll). Lou’s first great soul mate, mirror, and collaborator, whom he roomed with in his sophomore year, was the brilliant, eccentric, talented, but tortured and doomed Lincoln Swados. Swados came from an upwardly mobile, middle-class, and, by all accounts, outstandingly empathetic Jewish family from upstate New York. Like Reed, he had a little sister called Elizabeth, upon whom he doted (and to some extent, like Lou, identified with). The two students fell into each other’s arms like lost inmates of some Siberian prison of the soul who finally discover after years of isolated exile a fellow voyager. To make matters perfect from Lou’s point of view, Lincoln was an aspiring writer (working on an endless Dostoyevskian novel); his favorite singer was Frank Sinatra; Lincoln’s side of the room was covered in more crap than Lou’s; and—this was the clincher—Swados was agoraphobic. He spent most of his time holed up in their basement room either hunkered over a battered desk or playing Frank Sinatra records and rapping with Lou. Whenever Lou needed a receiver for one of his new songs, poems, or stories, Lincoln was always there. Their relationship was the first of many constructive collaborations in Lou’s life.

One of Lou’s strongest personalities was the controlling figure who always needed to be the center of attention and the most outstanding person in the room. Here again Lincoln was his perfect match, for if Lou ever worried that he might not yet possess the hippest look in the world, Lincoln presented no threat. He was usually togged out in a pair of pants that ended somewhere above his ankles and were belted in the middle of his chest. His customary short-sleeve shirt invariably clashed with the pants. A pair of bugged-out eyes that made Caryl Chessman in the electric chair look like a junkie on the nod stared out of a cadaverous face capped by a head of dirty, disheveled blondish hair. Lincoln’s body was as much of a mess as was his mind. He rarely bathed or brushed his teeth and at times emanated an odor that obviated any close physical relationships. The whole ensemble was tied together by a disembodied smile that clearly indicated, at least to somebody of Lou’s perceptiveness, just how far out in space Lincoln really was most of the time.

Their basement room was furnished like some barren writer’s cell out of Franz Kafka’s imagination. The two black iron bedsteads, identical desks, and battered chairs ensconced upon a green concrete floor and lit by a harsh bare lightbulb could not have better symbolized both the despair and ambition at the heart of their twin souls. They both despised the world of their parents from which they had at least temporarily escaped. Both were intent upon destroying it and all of its values with some of the most vitriolic, driven pages since Burroughs spat Naked Lunch out of his battered typewriter in Tangier. The room became their arsenal, their headquarters, their cave of knowledge and learning, and the engine of their voyage into the unknown. In time, Lou would rip off Lincoln’s entire repertoire of attitudes, gestures, and habits. Lou later confessed, “I’m always studying people that I know, and then when I think I’ve got them worked, I go away and write a song about them. When I sing the song, I become them. It’s for that reason that I’m kind of empty when I’m not doing anything. I don’t have a personality of my own, I just pick up other people’s.”

Having met his male counterpart, Lou now needed, in order to pull out the male and female sides warring within him, a female companion. Within a week of settling in with Swados, Lou saw her riding down the university’s main drag, Marshall Street, in the front seat of a car driven by a blond football player who belonged to the other Jewish fraternity on campus and recognized Reed as their local holy fool. Thinking to amuse his date, a scintillatingly beautiful freshman from the Midwest named Shelley Albin, he pulled over, laughing, and said, “Here’s Lou! He’s very shocking and evil!” making, as it turned out for him, the dreadful mistake of offering “the lunatic” a ride.

Although in no way as twisted and bent as Lincoln Swados, Shelley was as perfect a match for Lou as his roommate was. Born in Wisconsin, where she had lived the frustrated life of a beatnik tomboy, Shelley had elected Syracuse because it was the only university her parents would let her attend. In preparation for the big move away from home, Shelley, along with a childhood girlfriend, had come to Syracuse fully intending to mend her ways and acquiesce to the college and culture’s coed requirements. Discarding the jeans and work shirts she wore at home, she donned instead the below-the-knee skirt, tasteful blouse, and string of pearls seen on girls in every yearbook photo of the period. When Lou hopped into the backseat eager to make her acquaintance, Shelley was squirming with the discomfort of the demure uniform as well as her dorky date’s running commentary.

She vividly recalled Lou’s skinny hips, baby face, give-away eyes, and knew “we were going to go out as soon as he got into the car.” She also knew she was making a momentous decision and that Lou was going to be trouble, but that it certainly wasn’t going to be boring. “It was such a relief to see Lou, who was to me a normal person. And I was intrigued by the evil shit.”

The feeling was clearly mutual. As soon as the couple let Lou off in front of his dorm, Reed sprinted into their room and breathlessly told Swados about the most beautiful girl in the world he had just met, and his plans to call her immediately.

Lincoln had a strangely paternal side that would often appear at inappropriate moments. Seeing his role as steering Lou through his emotional mood swings, Swados immediately put the kibosh on Reed’s notion of seducing Shelley by informing him that this would be out of the question since he, Lincoln, had already spotted the pretty coed and, despite not yet having met her, was claiming her as his own.

Lou, for his part, saw his role in the relationship as primarily to calm the highly strung, hyperactive Swados. Reasoning that the nerdy Lincoln, who had been unable to get a single date during the freshman year, would only be wounded by the rejection he was certain to get from Shelley, Lou wasted no time in cutting his friend off at the pass by calling Shelley at her dorm within the hour and arranging an immediate date. That way, Lou told himself, he would soon be able to give Swados the pleasure of her company.