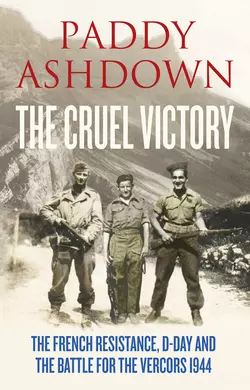

The Cruel Victory: The French Resistance, D-Day and the Battle for the Vercors 1944

Paddy Ashdown

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Книги о войне

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 536.55 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: From the bestselling and prize-winning author of ‘A Brilliant Little Operation’ comes the long neglected D-Day story of the largest action by the French Resistance during WWII, published to coincide with the 70th anniversary of the Normandy landings.In early 1941, three separate groups of plotters – one military, one political, one intellectual – began to organise and plan on and around the forbidding mountainous plateau near Grenoble – the Vercors. The aims of the groups were the same: to hasten the departure of the German occupiers; to restore the pride of France after its fall and the humiliations of the puppet Vichy government which followed; and to build a new France. The overwhelming desire to get rid of the Germans would unite them. Their different views of the France they hoped for in the future would divide them.Over the next three years these sparks of resistance would grow to challenge the might of the hated German occupiers. As the Allied troops stormed the D-Day beaches, the Vercors rose up to fight the Nazis in a planned rearguard action. It was to prove not only the largest Resistance action of the entire war but also, in the severity of the German response, the most brutal crushing of resistance forces in Western Europe.For the men and women of Vercors, aided and abetted by the Free French forces of General de Gaulle and SOE operatives from London, the events on the Vercors took them on a journey from early idealism through hope, misjudgement, folly, despair, sacrifice and slaughter to a kind of cruel victory. The tragedy drew the attention of those at the highest level of the Allied war effort and placed the Vercors deep into the heart of the history of modern France in a way which resonates still in the country’s daily life and politics.Long overlooked by English language histories, this magnificent book sets the story in the context of D-Day, the muddle of politics and many misjudgements of D-Day planners in both London and Algiers, and – most importantly – it gives voice to the many Maquisards fighters who fought to gain a voice in their country’s future.