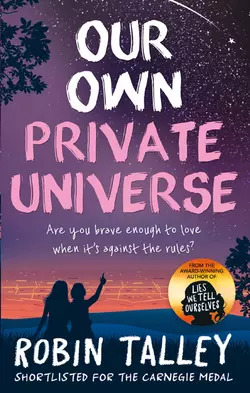

Our Own Private Universe

Robin Talley

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Детская проза

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 458.46 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ’Talley’s newest is sure to satisfy.’ – Kirkus ReviewsFifteen-year-old Aki Simon has a theory.And it’s mostly about sex.No, it isn’t that kind of theory. Aki already knows she’s bisexual–even if, until now, it’s mostly been in the hypothetical sense.Aki’s theory is that she’s only got one shot at living an interesting life–and that means she’s got to stop sitting around and thinking so much. It’s time for her to actually do something. Or at least try.So when Aki and her friend Lori set off on a trip to a small Mexican town for the summer, and Aki meets Christa–slightly-older, far-more-experienced–it seems her theory is prime for the testing.But something tells her its not going to be that easy…