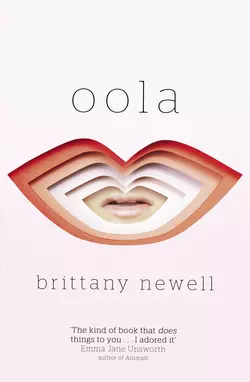

Oola

Brittany Newell

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 883.81 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ‘It′s the kind of book you want to linger in and never leave; the kind of book that DOES things to you . . . I adored it’ Emma Jane Unsworth, author of AnimalsOOLA is a very different kind of love story.Oola and Leif meet at a party in East London, two Americans at a loose end. The insouciant music school dropout and aimless young writer fix on one another, grab hands and fall head-first down love’s rabbit hole.Leif’s summer plans soon become Oola’s too and the pair find themselves mansion-sitting their way across the States, drinking the liquor cabinets dry and emptying the walk-in wardrobes to play dress-up. But when they decide to play house in a Big Sur cabin, where the clapboards quiver in the heat, boredom breeds an idea that could extinguish their love and even destroy them both.This is a love story like no other. A savagely brilliant exploration of what it is to adore, own and inhabit your beloved. OOLA takes you to the line and shows you how to cross it.From an electrifying new voice, this astonishing debut is as juicy and provocative as it is beautiful.