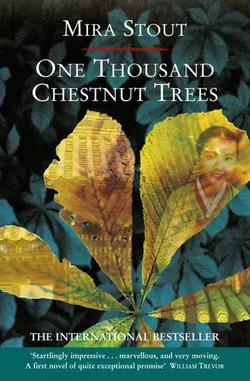

One Thousand Chestnut Trees

Mira Stout

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 853.17 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: An epic tale of an enigmatic land – Korea – and one woman’s search for her past.Uncle Hong-do arrives in Vermont from Korea to see the sister he has never met, a concert violinist long settled in America. His colourful visit turns his teenage niece Anna’s world upside down, disrupting her cosy existence with his eccentric customs, forcing into it a fresh and intriguing tang of Korea. Then, too soon, he returns to Seoul.When Anna leaves for the orient many years later to uncover her family’s elusive history, her departure stirs up vivid, shocking memories for her mother, of her gilded childhood in Korea and the story of her noble clan’s fall from power.Long ago, her grandfather, Lord Min, commanded his own private armies and his vast estates straddled North and South. In defiance of centuries of barbarous invasions – by the Japanese, Manchus, and finally the Communists – he built a temple high in the mountains, and planted one thousand chestnut trees to shield it from view. Now, generations later, his trees call back his great-granddaughter, and Anna sets out with Uncle Hong-do to find the hidden temple.A powerful mixture of memoir and fiction – the Wild Swans of Korea.