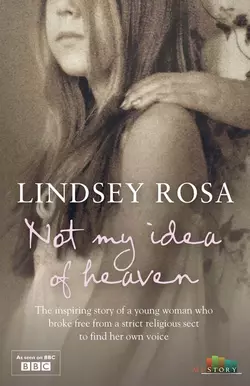

Not My Idea of Heaven

Lindsey Rosa

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Социология

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 191.96 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 28.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Those who had not discovered our truth had Satan in their hearts. We lived amongst them, but not with them, ′in the world, but not of the world′. We were special.We were the disciples of the Fellowship.When she was a child, Lindsey Rosa′s every waking moment was governed by the rules of an extreme separatist sect. It controlled what she wore and what she ate; it forbade her to listen to music, to cut her hair, to watch television, to use a computer. The Fellowship said her family was special. Why would she believe otherwise?Then, when Lindsey was seven, her elder brother was caught listening to music and the family were expelled from the sect. But Lindsey′s parents knew nothing but the ways of the Fellowship, so they remained in hope that they would be accepted and continued to make the family live by the sect′s strict rules – cutting themselves off from their local community.But as Lindsey grew, so too did her awareness of a world outside. And, feeling increasingly isolated, she struggled with her own identity. Until finally she was faced with a devastating choice: to continue to live by the rules of the religious sect or to be brutally cast out and leave the family she loved behind forever.