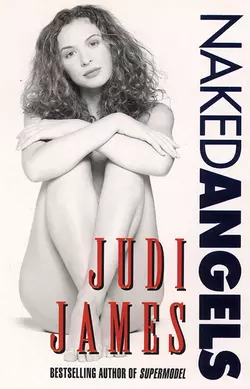

Naked Angels

Judi James

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 544.32 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Evangeline is at the pinnacle of her career as a famous fashion photographer when she meets Mik, a moody Hungarian war-photographer driven by ruthless ambition. Though they are drawn to one another as lovers, their professional rivalry spells doom.THEIR LOVE IS SWEET POISON…Evangeline, ugly-lovely daughter of famous American artists, is a top fashion photographer. Mik, moody, Hungarian, would like to be. When they meet on a London shoot, they are immediately drawn together as lovers, but, both driven by ruthless ambition, their clash spells doom…Each is haunted by secret tragedy. Both have sacrificed private happiness for public success. Both are victims who inflict their pain on others.′Naked Angles′ is their story, of greed and glamour, of suffering, destructive passion and, finally, of hope and unexpected happiness…