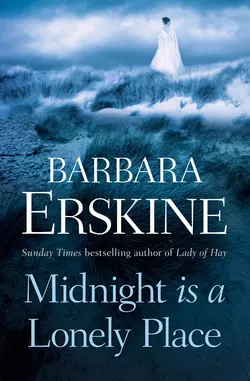

Midnight is a Lonely Place

Barbara Erskine

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 699.98 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Beautifully repacked edition of this stunning novel of contemporary and historical betrayal and revenge, from the author of LADY OF HAYAfter a broken love affair, biographer Kate Kennedy retires to a remote cottage on the wild Essex coast to work on her new book, until her landlord′s daughter uncovers a Roman site nearby and long-buried passions are unleashed…In her lonely cottage, Kate is terrorized by mysterious forces. What do these ghosts want? Should the truth about the violent events of long ago be exposed or remain concealed? Kate must struggle for her life against earthbound spirits and ancient curses as hate, jealousy, revenge and passion do battle across the centuries…