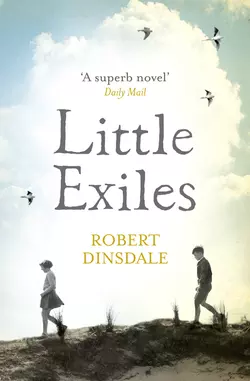

Little Exiles

Robert Dinsdale

A stunning novel set in the wake of the Second World War, Little Exiles tells the extraordinary story of the forced child migration between Britain and Australia that took place after World War II and how this flight from home shaped the identity of a generation of children.Jon Heather, proud to be nearly nine, knows that Christmas is a time for family. But one evening in December 1948, no longer able to cope, his mother leaves him by a door, above which the legend reads Chapeltown Boys’ Home of the Children’s Crusade. Several weeks later, still certain his mother will come back, Jon finds himself on a boat set for Australia. Promised paradise, Jon soon realizes the reality of the vast Australian outback is very different; its burnished desert becoming the backdrop for a strict regime of hard work and discipline.So begins an odyssey that will last a lifetime, as Jon Heather and his group of unlikely friends battle to make their way back home.

LITTLE EXILES

ROBERT DINSDALE

It is proposed that the Commonwealth seek out in Britain, by whatever means necessary, at least 17,000 children a year suitable and available for immediate migration to Australia.

Arthur Calwell, Australian Minister for Immigration, 1949

Table of Contents

Title Page (#u9db28473-240e-58ab-9adc-00e8551f35d2)

Epigraph (#uf6d1db36-44c0-52a0-9230-db6867f267c3)

Book One: The Children’s Crusade (#u6d8b8147-a6ea-5c20-8a25-00017e90bba7)

Chapter I (#uaab8dfbb-2b17-5680-9cfa-01ed9977da54)

Chapter II (#u7a188d86-389f-5bcc-97b8-5fba48096236)

Chapter III (#u03e07b02-9631-5149-a164-84735bb9c23b)

Chapter IV (#u053ae107-a46a-5b31-80e8-a4caa76263a0)

Chapter V (#u293395f3-46b1-5a87-b66d-1faaed8002a7)

Chapter VI (#u26199d64-a843-59b4-af5d-b2596a04975b)

Chapter VII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter VIII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter IX (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter X (#litres_trial_promo)

Book Two: The Stolen Generation (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XI (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIV (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XV (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XVI (#litres_trial_promo)

Book Three: The Three Childsnatchers (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XVII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XVIII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIX (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

BOOK ONE

I

The boy standing vigil at the end of the lane, a Christmas lantern in his hand, still believes his father is coming home. Christmas, he has been taught, is a time of family, when errant sisters might come back to the fold, when black-sheep brothers might go carolling with the mothers they say they despise. He is eight years old, proud to be nearly nine, and he still recalls last Christmas, how he stood at the end of the lane, tracking every approaching motor car until the snow drifts climbed above his boots. It had taken his mother to prise him away. She had hoisted him up and hauled him back to the terrace, where his sisters were ready to welcome him with hot mulled wine – which was terrible to taste, but at least made him feel warm and fuzzy inside. He had gone to bed that night in squalls of tears, but risen the next morning to presents under the tree – a book he had pined for, The Secret of Grey Walls, a cap gun he had been told, time and again, not to expect – and it was not until the evening that he realized he had not thought of his vigil all through the day. This year, he has resolved, he will not be so cowardly. He has his cap gun tucked into his belt, he has brought mulled wine in a flask, and he has wrapped up warm. Christmas is a time of family and a time of miracles. The logic will not be denied.

It is 1948 and, though he has never once seen his father, he knows that he is coming home.

He was born in the middle month of winter in the year of 1940. He has twin sisters older than him by eleven years, and they are the ones who attended his birth, straining with his mother in the backroom of the terrace where they live. Of his earliest years, he remembers little. His mother kneads dough in a bakery before dawn and cleans houses in the afternoon, and it is his sisters he remembers making him breakfast and dressing him every morning. He grows up, quickly, between one end of the street and another. A shop mistress smiles when he enters her shop, secretly palming barley sugars into his hands. A neighbour invites him to play with her daughter in a backyard on the other side of the road. So lost is he in this world of women that it is not until he sees two brothers tumbling over one another further down the terrace that he discovers it is cowboys and Indians he longs to be playing, not with dolls’ houses and ponies chipped out of wood.

At night, there are sirens. If the sirens sing before dusk, they hurry together to a shelter buried in the grounds of a house at the end of the terrace. Outside, the world quakes. Through a speak-hole sliding back and forth, the boy can see cascading oranges and reds, great reefs of smoke. He hears whispers of factories on fire and great barrage balloons strung through the skies.

If the sirens do not sing until after dark, they remain in their house, crammed into a cubbyhole beneath the stairs. Sometimes the building shakes. At first, the boy does not understand the fear – but, in the tomb under the stairs, terror is a disease that spreads quickly. One night, crammed into that cubbyhole, his mother begins to sob. The boy believes he can hear his own name in the tears: Jon, Jon, Jon, the word swallowed by the song of the siren.

He is five years old when he begins to ask about his father. It is 1946 and there are suddenly strange men in the streets, great companies of them descending on the taprooms and alehouses. Jon watches them from his window at the top of the terrace. He notices, for the first time, that his mother stands alone at the end of their lane each evening, watching these strange intruders march back from the ruins of warehouses and factories they are rebuilding. He wonders if she too is bewildered at the invasion of their city, but his sisters smile oddly when he dares to ask the question. They tell him she is waiting. Nothing more, and nothing less. She is waiting for their father to return.

They bring out photographs. A man with wild black hair glowering into the camera. A man with two young girls, one sitting on either knee. His name, they tell him, is Jonah, though he too is always known as Jon. It thrills the little boy to think that he, one day, might be like the man in the pictures.

At the back end of summer, a man in uniform arrives at the house next door, and the little girl with whom Jon is sometimes invited to play is introduced, for the first time, to her father. Jon watches as the man pauses, the little girl framed in the doorway, and crouches to urge her forward. At first she freezes, her mother looming behind. Then the man vaults the brick wall, scooping up the child and embracing her mother in one swift movement. In some of the other doorways along the redbrick row, other women have appeared to witness the reunion. One of them, Jon notes, begins to applaud.

There are stories to be learned. His father was a hero fighting a crusade on the other side of the world. His father was in the jungle teaching the natives to fly Spitfires. There are other stories as well – his father once worked at a lathe; his father was arrested in a backroom brawl – but these are not the tales with which the boy obsesses. Though the boy has never once met the man, he wants to grow up and be just like him, out in the world on grand adventures, with friends and family at home thrilling for news of his exploits.

He begs his mother every evening to tell some other tale of his father’s derring-do. Sometimes he is swooped away by his sisters – but, sometimes, he is wily enough to trap his mother in the question. One night, after his sisters have put him to bed, his mother returns from an evening sweeping some factory floor. He waits for her to climb, wearily, to her bed – and then he pounces. He tells her he has had a nightmare, that he dreamed of his father lost, somewhere at sea, fending off sharks with the butt of a broken oar.

It is nonsense, she tells him. His father cannot swim; he would never have got himself into such trouble in the first place.

The boy does not notice, at first, when the stories stop being told. He supposes it may have been earlier than he first thought, for he was surely telling himself the stories as well, lining up his lead soldiers and imagining them his father’s company, or building matchstick planes and putting his father in the cockpit. In his games, his father makes his way home from the jungles on the other side of the world, but is forever sidetracked by helpless villagers, or orphaned children searching for someone to protect them. Each time he goes to sleep he constructs a new fantasy, some other adventure his father cannot resist as, kingdom by kingdom, he picks his way back to English shores.

In a journal he writes stories about his father. At first, they are only short passages, idle thoughts: his father parachuting from a plane; his father in a coracle, tumbling helplessly over a wild waterfall. He is beginning to compose a longer story – his father crossing Siberia by sled with Nazis on his trail – when his mother discovers him at work, hidden under the bedcovers. He does not understand why she starts crying. She takes the journal away and forbids him from writing such stories ever again.

He is not permitted, any longer, to mention his father.

The winter of 1949 lingers long into the following year, but lasts longer still for Jon’s mother. She is at home more and more often, lying in bed until hours after dawn, so that soon it is Jon’s sisters who cook breakfast and scrub his laundry and take the ration books out to gather the week’s groceries. On Christmas Day, she does not get out of bed at all. They open presents gathered around her bed, and bring a small tree into the room that Jon has decorated with stray strands of tinsel. Early in the New Year, he finds one of his sisters sobbing quietly to the other in the scullery. He listens at the door, but they are well versed in his ways and shoo him away.

Three nights later, Jon piles his few belongings – clothes and bedspread and a bundle of treasured books – into a suitcase and follows his sisters to a neighbour’s house. He spends the night on the floor of the living room, where the deep rug before the fire is a more comfortable bed than he has ever known. He wonders, absently, why their mother has not joined them in the adventure, but is promised he will see her again soon.

Three nights later, his mother arrives on the doorstep and takes dinner with them: a broth made of onions, thickened with potato. She has brought hard bread from her bakery, but its appearance on the table causes deep and troubled sighs. His mother has stolen it, Jon understands – but a little theft does not damage its taste.

She comes intermittently after that. One Sunday, she strolls with him along the canal. Another time, she and his sisters go for a long walk – and only his sisters return. Easter comes, and she brings him a new book, wrapped in brown paper and tied up with string. He has been waiting for Mystery at Witchend longer than he remembers, and is so eager to sink into its pages that he does not realize, until it is already dark, that his mother stayed only a few minutes that day.

By the break of December in the year of 1950, he has not seen his mother in four long months. Christmas approaches quickly, and he is determined it will not be like the last. He makes plans to go to the old spot, to keep his customary vigil – but, just as he is preparing to leave, a familiar voice rises in the hallway below. Thundering down the stairs, he sees his mother standing in the door.

He does not run to her, though he knows it is what she expects. At the command of his sister, an adult now, he approaches gingerly.

His mother crouches and tells him that she loves him. He accepts the words, because he has always accepted them, has never for a second doubted she does not think of him as often as he thinks of her. She tells him to put his best coat on, to polish up his boots and gather together the books she knows he loves. At last, the boy understands: Christmas is a time of family and a time of miracles.

They are going back home.

Through the redbricks, piled high in frost and ice, he trails after his mother. They wander the old street, but they do not go back to the old house. They march on, instead, into thoroughfares Jon has never known, strange, foreign streets where black men stand out in the snow. They come to a broad thoroughfare from where he can see the lands beyond the edge of the city. There has been snow on the dales for many days now, and they loom luminescent in the night. A silvery moon hangs above, shipwrecked in banks of white cloud.

Between two houses, their windows boarded up, a lane drops onto a street below. Thorn trees grow wild along the verge and, to Jon, it appears like the entrance to some fairytale forest.

His mother stops and crouches down so that his face is only inches from hers. Her eyes are shimmering. She produces an envelope and presses it into his hands. Do not read it, she implores. A smile flourishes and dies on her face. She knows how Jon loves to read – but the letter is not for him. He is only to pass it on.

She turns him to the alley flanked with trees. At its end, lights are burning in the windows of a sprawling redbrick pile. It will not be forever, she tells him. But there is no place for Jon with his sisters any longer. They have carried him where she alone could not, and they can take him no further. Yet, his mother will be well soon. She will have money, she will have a home, she may even have a man of her own. She brushes the hair out of his eyes, and turns him on the spot to usher him on his way. She will come for him before the new year is two months old – but, for now, he must float on alone.

Jon stands alone as his mother returns to the terrace. At moments his feet compel him to follow, but he is strong enough – defiant as he knows his father must have been – to remain rooted to the spot. Only when she is gone from sight, wreathed in a sudden flurry of snowflakes, does he fail. He fumbles after her for one step, and then another – and then he stops. It is not what she wants. It is not what his father would have wanted.

He turns to the trail, tucking the letter into his coat. He can see, now, that the redbrick pile is not one building but three, two houses hunching on the shoulders of a hall with a spire like a church. He walks, slowly, between two pillars of red brick. Then, down the ledges he goes, head held high so that none of the midnight creatures watching him from the trees might see that he is afraid.

In front of the tall spire there lies an open yard, where a motor car sits on blocks of stone and a single bicycle is propped against the wall. Washing lines criss-cross above him, beaded with snow. He advances slowly. The building looms, a fairytale castle made out of bricks and mortar.

Above the door, the legend reads, in cursive script, Chapeltown Boys’ Home of the Children’s Crusade. Beneath that, a shield is mounted on a tall cross, and emblazoned with words Jon has to squint to make out.

We fight for the paupers and not for the princes. We fight for the orphaned, the lost and the lonely, the forgotten children of famine and war, the desperate ones who deserve a new world.

Jon barely has time to finish the final words when the doors on the other side of the yard open. Beyond them, he sees children – short and tall, young and younger still, more children than he has seen in his life – and, above them, wrapped in long robes, a man in black.

The man gestures to him. ‘Jon Heather,’ he intones, his voice old and feathery. ‘We are so very glad that you have found us.’

II

‘That little one’s still in bed,’ a voice, full of mirth, whispers.

‘Might be he froze in the night.’

The first voice pauses, as if weighing the idea up. ‘He’d have a better chance of not freezing if you gave him back his blanket.’

Once the voices have faded, Jon Heather opens his eyes. In truth, he has been awake since long before the morning bell, just the same as every last one of the mornings he has been here. At night, long after lights out, he forces himself to stay awake for as long as he is able, just so that they might not take his sheets, but even so, he wakes every morning to discover that his sleepiness has betrayed him, that he’s been sucked under, that now he’s shivering on a bare mattress with only the ceiling tiles to shelter him.

Once he is certain the dormitory is empty, he squirms back into yesterday’s clothes – they are two sizes too big, hand-me-downs he was given once he had worn out the clothes in which his mother sent him – and ventures out of the room. If you are careful, you can walk the length of the landing without your head once peeping above the banister rail. It is a long passage, and overlooks a broad hall below. Along the row, there are other dormitories and, at the end, the cell where the returned soldier who leads them in games sleeps. Jon Heather steals past each doorway, mindful of other stragglers, like him, trying to avoid the stampede.

At the top of the stair, he stops. Here, the stairs cut a switchback to the entrance hall below. Standing at the top, he gets a strange sense of things out of proportion, of the downstairs world drawing him in. He pauses, fingering the banister for balance. Through a gap between the rails, he can see the big double doors through which he first came, holding up his mother’s letter like a petition. He has stood here every morning, waiting for her face to appear at the glass, or else for his sisters to come, raining their fists at the door and demanding his return. So far: stillness and silence, more terrifying than any of the dreams that have started to taunt him.

The hall below is stark, with a counter at the front like an old hotel. At the doors stand two of the men in black, conversing in low whispers. The elder is the man who first welcomed Jon to the Home. Wizened like some fairytale grandfather, he wears little hair upon his head. Beside him, another man listens attentively. Somehow, his skin is tanned by the sun, a stark contrast to the pallid men who shuffle around this place.

Jon wants to wait until they have passed before descending the stairs, but presently the elder man turns, sunken eyes falling on him.

‘The bell,’ he says, ‘was more than fifteen minutes ago.’

Jon, wordless, shrinks back, even though he is a whole staircase away from the man.

‘Breakfast. No exceptions.’

The men in black leave the hall along one of the passages leading deeper into the building. These are hallways along which the boys are forbidden to go, and all the more mysterious for that. At the bottom of the stair, Jon listens to their footfalls fade, and wonders how far the sprawling building goes.

Now, however, he is alone.

He can hear the dull chatter of boys in the breakfasting hall, which joins the entrance hall behind the counter, but something pulls him away, draws him towards the big double doors. The glass windows on either side are opaque, barnacled in ice, so that the world beyond is obscured. He stands, tracing the pattern of an icy crystal with his index finger, before his eyes fall upon the door handle. Then, suddenly, his hands are around it. At first, that is enough – just to hold on to the promise of going back out. Yet, when he finds the courage to turn the handle, he finds it jammed, locked, wood and steel and glass all conspiring against him.

Jon Heather pads into the middle of the entrance hall and turns a pointless pirouette.

Breakfast is the same every morning: milk and oats. Sometimes there is sugar, but today is not one of those days; there will be no more sugar until the boy who wet his bed and secretly changed his sheets is discovered and punished. By the time Jon Heather arrives, most of the boys are already done eating – and, because they are not allowed to leave the hall until the second bell sounds, they are now contriving games out of bowls and spoons. They sit at long tables, skidding bowls up and down, crying out the names of famous battles of which they have heard. One boy, who has not been quick enough in wolfing down his oats, has found his bowl upended and perched on top of his head like a military cap. The oats look like brain matter seeping down his cheeks.

‘Just get it off your head, George, before one of them old bastards sees.’

‘It’s hot …’ the fat boy trembles.

‘More than mine was,’ says the lanky, red-haired boy beside him, shoving his bowl away. ‘Look,’ he whispers, out of the corner of his mouth, ‘you can eat up what’s left of mine if you like. Just don’t make me have to take that thing off your head for you.’

‘I wish you would, Peter. It’s getting in my hair.’

The lanky redhead groans. His head drops to the table for only an instant, before he sits bolt upright, swivels and helps the younger boy lift off his new helmet. ‘I’m never going to hear the end of this from the other boys …’

‘It’s in my ears, isn’t it?’

The older boy digs a finger in and produces a big clot of porridge. ‘You want me to wipe your arse as well, Georgie boy?’

Jon Heather must walk the length of the breakfasting hall to get his porridge from the table at the front. When he gets there, all that is left are the congealed hunks at the bottom of the pan – but this is good enough; it’s a tradition for each boy to hawk up phlegm into the pot as he takes his portion, and most likely it didn’t sink this far. Besides, Jon isn’t hungry. He carries a metal bowl back to a spot at the end of the table and pretends to eat.

Two months. He is only staying a short two months. His father has surely endured much worse, locked up in some jungle camp for years on end.

‘You’re new,’ a boy, tall with close hair and sad, sloping eyes, begins, flinging himself onto a stool opposite Jon.

Jon does not know how to reply. ‘I am,’ he says – but then the second bell tolls, and he is spared the onset of another inquisition.

During the day, there are sometimes lessons. The men in black sit them down in the chantry, which squats on the furthest side of the entrance hall, and give them instructions in morals. Mostly, this means how to be good, but sometimes how to do bad so that good might prosper. This, the men in black explain, is a difficult decision, and to shy away from it would be the Devil’s work. When there are not lessons, the boys are left to their own devices. Often, the men in black disappear into the recesses of the Home, those strange uncharted corridors in which they study and live, leaving only a single man to prowl among them, making certain that the boys have made the best of their lessons and are growing into straight, moral young men. Today it is the sun-tanned man in black. Periodically, he appears in the doorway to summon a boy and take him through long lists of questions – What is your age? How long have you been here? Are you an adventurous sort, or a studious sort? – before propelling him back to his games.

Jon is hunched up in the corner of the assembly hall, listening to bigger boys batter a ball back and forth, when the sun-tanned man appears. He seems to be counting, with little nods of his head, eyes lingering on each boy in turn. Every so often, his face scrunches and he has to start again, as the gangs the boys have formed come apart, scatter, and then reform. In the middle of the shifting mass, Jon Heather sits with his knees tucked into his chin. Come night-time, at least there will be order; at least there will be a place allotted for each boy; at least the day will be over. Even if he has to sleep in the biting cold without his blanket again, listening to the whispers of the boys around him, watching the shadow of footfalls outside the dormitory door, it won’t matter. Every nightmare is another night gone, and every night gone is another few hours closer to the morning when his mother will return.

The man in black’s eyes seem to have fallen on another boy, the lanky redhead from breakfast, but something compels Jon to stand up. Dodging a rampaging bigger boy, he scurries to the doorway. At first, the sun-tanned man does not even notice the boy standing at his feet. Jon reaches up to tug on a sleeve. His fingers are just dancing at the hem of the cloth when the man looks down: violent blue eyes set in a leathery mask.

‘I have a question,’ Jon pronounces.

‘A question?’ The accent is strange, English put through a mangling press and ejected the other side.

‘I want to call my father. He’s coming to fetch me.’

The man in black nods, as if he has known it all along.

‘I didn’t know who to ask,’ Jon ventures.

‘I see,’ the man says, placing an odd stress on the final word. ‘And when was the last time you saw your father? Was it, perhaps, the night he brought you here?’

‘My mother brought me here,’ says Jon, exasperated at the man’s stupidity.

‘And your father?’

Jon Heather says, ‘Well, I haven’t once seen my father.’

The man gives a slow, thoughtful nod. He crouches, a hand on Jon’s shoulder, but even now he is some inches taller and has to look down, along the line of a broad, crooked nose. ‘Then it seems to me, you hardly have a father at all.’

At once, the man climbs back to his feet, barks out for the red-haired boy and turns to lead him along the corridor.

Alone in the doorway, Jon Heather watches.

‘If you keep letting them take it, they’ll carry on taking it,’ the boy with red hair snipes. Tearing Jon’s blanket from the hands of a bigger boy, he marches across the dormitory and flings it back onto Jon’s crib. ‘What, were you raised as a little girl or something? Just tell them no.’

‘Thank you.’

‘Yeah, merry Christmas,’ the redhead replies.

Christmas Day has been and gone. This year, no card from his mother, no parcels wrapped in string with his sisters’ names on them. All of this he can bear – but he cannot stand the thought that, this Christmas, he kept no vigil for his father’s return.

It is the small of the afternoon and outside fresh snow is falling. Ice is keeping them imprisoned. Jon tried to hole up in the dormitory today, but with the grounds of the Home closed, clots of bigger boys lounge around their beds, working on ever more inventive ways to stave off their boredom – and Jon knows, already, what this might mean. If you tell tales to the men in black, they give you a lecture on the spirit. If you tell tales to the soldier at the end of the hall, he bustles you to a different room and, by the time you look back, he is gone. It is better, Jon decides, to stay away. A man, he tells himself, can endure anything at all, just so long as he has his mother and father and sisters to go back to.

He bundles up his blanket and tucks it under one arm. Then, with furtive looks over each shoulder, he bends down and produces a clothbound book that has been jammed beneath his mattress. He could read We Didn’t Mean to Go to Sea a hundred times – he’ll read it a hundred more, if it makes these two months pass more quickly.

‘Where’re you creeping off to?’

It is only the red-haired boy again, suddenly rearing from a bottom bunk where he has been tossing the rook from a game of chess back and forth. On his elbows, he heaves himself forward.

‘I’m going to find a corner,’ Jon says.

‘Down in the chantry?’

Jon shrugs. The Home is still a labyrinth of tunnels and dead chambers, and he has not given a thought to where he might retreat. There are passages along which the boys know not to go, but mostly these lead only to barren rooms, boarded-up or piled high with the things past generations of boys have left behind. A brave expedition once found a box of tin soldiers here which they brought heroically back and refused to share – but not even those brave boys have dared to sneak in and spend the night in that deep otherworld. Bravery is one thing, they countenance, but foolishness is something else. At night, those rooms are stalked by the ghosts of children who died there.

‘Maybe I’ll go to the dead rooms,’ Jon says, for want of something better to say.

‘Well,’ the red-haired boy goes on, allowing himself a smirk at this new boy’s ridiculous pluck, ‘you see George, you tell him I’m looking for him. I said I’d come looking, but I aren’t ready yet. You tell him that.’

‘Which one is George?’

‘The chubby one. Got no right carrying fat like that in a place like this.’

The one who wore a cap of milk and oats at breakfast, Jon remembers. He sleeps in the bunk beside the red-haired boy and wakes early every morning to hang out his sheets to dry. On his first morning in the Home, Jon saw the red-haired boy shepherding him out of the dormitory and returning with crisp sheets stolen from the laundry downstairs.

‘I’ll tell him,’ says Jon.

In the end, Jon does not dare follow the long passage from the entrance hall and venture into the boarded-up rooms. Instead, head down so that he does not catch the eye of a man in black scolding two boys for playing with a wooden bat, he slopes across and finds a small hollow behind the chantry, where old furniture is piled up and blankets gather dust. It is cold in here, but Jon huddles up to leaf through the pages of his storybook. So engrossed is he that he does not, at first, register the portly figure who uncurls from a nest of dustsheets.

Suddenly, eyes are upon him. When he looks up, the chubby boy is standing in front of him, holding out a crumpled blanket as if it is both sword and shield. He is shorter than Jon remembers, with hair shorn to the scalp but now growing back in unruly clumps. His lips are red and full, and the bottom one trembles.

‘I just want to …’

Jon scrambles up. ‘I’m sorry,’ he begins. ‘I didn’t know anybody came here.’

The fat boy shrugs.

‘You’re George.’

The boy squints. He seems to be testing the name out, turning it over and again on his tongue. Then, head cocked to one side, he nods.

‘There’s a boy up there, said he was looking for you …’

At that, the boy seems to brighten. ‘That’s Peter,’ he says. ‘He said he’d come soon.’

Jon shuffles against the stack of chairs, as if to let the boy past.

‘You don’t mind if I stay? Just a little while?’

Jon shrugs, sinks back into his blanket.

‘I come here before stories sometimes.’

Jon falls into his book, but he has barely turned a page before he hears the boy strangle a bleat. When he looks up, torn out of some countryside adventure – Jon has never seen the countryside, and marvels that people might live in villages on hills, climbing trees and boating on lakes – the boy is too slow to hide his tears. There is a lingering silence, and Jon returns to his tale: two boys are scrambling to moor a boat as fog wreathes over the Fens.

Again, the boy chokes back a sob. This time, Jon looks up quickly. Their eyes meet. The boy strangles another sob, and then rushes to mask the fact that he has been crying. For a second, his eyes are downcast; then, by increments, he edges a look closer at Jon.

At last, Jon understands. The boy wants his crying to be heard. ‘What’s the matter?’

The boy shrugs oddly, his round shoulders lifting almost to his ears. ‘What’s your name?’

Perhaps he only wants to talk – but, if that is so, Jon cannot understand why he is cowering in this cranny at all. ‘I’m Jon.’

George gives a little nod. ‘There was a Jon when old Mister Matthews brought me here. He was one of the bigger boys. He wasn’t here for long.’

‘He went home?’

George shakes his head fiercely. ‘I think the men sent him somewhere else.’

Jon considers this silently. There might be no more than six or seven men in black roaming these halls, but somehow it feels as if they are everywhere all at once. They are quiet men who speak only rarely, unless it is to lead the boys in prayers or summon them to chores – yet when a boy has done something wrong, been tardy in making his bed or been caught whispering after lights out, they have a way about them, a gentle nod that they give. Then, a boy must go to a corner and wait to be dealt with. He might find himself running laps of the building, or locked in the laundry. The other boys say that he might find himself in one of the dead rooms with his trousers around his ankles and red welts blooming on his bare backside. One night, a boy was caught chattering after dark and taken from the dormitory, only to come back an hour later with the most terrible punishment of all. ‘They’re writing to my mother,’ he said, ‘to tell her I’m happy and don’t want to go home …’

Surely, Jon decides, it is these men in black who are keeping him here. They have cast an enchantment on his mother, another on his sisters, and have raised up walls of ice around him.

‘What’s in your book?’

Jon inches across the floor, thick with dust, and holds the cover up so that George might see.

‘Peter used to read stories to me when they put me here …’

‘How long have you been here?’

‘It was before the summer. There was snow in May!’

Jon is about to start spinning the familiar story so that this fat boy might hear it as well, when somewhere a bell begins to toll.

There comes a sudden flurry of feet. Jon crams the book under a stack of chairs. At his side, George is infected by the panic and, knees tucked into his chin, rolls up into a ball.

The footsteps grow louder. Then, a short sharp burst: somebody calling George’s name.

‘George,’ the red-haired boy says, loping into the hollow with the air of an exasperated schoolteacher, ‘there you are …’

George unfurls from his bundle, throwing a sheepish glance at Jon. ‘I’m always here, Peter.’

The red-haired boy follows George’s eyes. ‘This one been pestering you, has he?’

Jon shakes his head.

‘He’s bound to pester someone, aren’t you, George?’ says Peter.

George eagerly agrees.

‘How are you doing, kid?’

The fat boy shuffles his head from side to side.

‘They told him about his mother last night. He told you about his mother?’ asked Peter.

‘My mother’s coming back for me,’ Jon begins. He does not know why, but he proclaims it proudly, as if it is an award he has striven for and finally earned.

‘Yeah,’ Peter says, slapping George’s shoulder so that the little boy stumbles. ‘That’s what George here thought as well. But they called him into the office last night and told him she wasn’t ever coming back. She’s dead, George. Isn’t that right?’

George nods glumly. It occurs to Jon that, though tears shimmer in his eyes, he is thrilled to hear it announced so plainly by Peter.

‘Me,’ says Peter, ‘I been here longer than George, longer than lots of these boys. My mother’s been cold in the ground for almost forever. My sister’s with the Crusade too, but they shipped her off to a girls’ home in Stockport, so it’s not like I’m ever seeing that one again.’ He exhales, as if none of it matters. ‘So the one thing you got to understand, kid, is that whatever’s coming up for you, it isn’t Sunday roasts and trips to the seaside.’

In the hallways outside, the bells toll again.

‘Come on,’ says Peter, ‘you don’t want to know what happens to boys who skip their stupid vespers …’ Peter scrambles past, out into the hall.

Momentarily, Jon and George remain, sharing shy glances. Then, Jon moves to follow.

George reaches forward and tugs at Jon’s sleeve.

‘She’s really coming back, is she? Your mother?’

Jon does not mean to say it so, but suddenly he is full of spite. He whips his arm free. ‘I’m not an orphan,’ he says. ‘I have a mother and a father, and they’re both coming back. I don’t care what Peter thinks – two months and I’ll be gone …’

They push across the hall. The straggling boys are hurrying now, down the stairs from the dormitories above.

‘That’s how it was for Peter,’ George begins, drying his eyes so vigorously that they become more swollen and red. ‘But it’s just like he always says. The childsnatcher doesn’t come in the dead of night. He doesn’t creep up those stairs and stash you in his bag.’ They follow a passage and go together through the chantry doors, where the other boys are gathering. ‘He’s just a normal man, in a smart black suit – but once he calls you by your name, you never see your family again.’

In the doorway, Jon hesitates. The boys are gathered around, sitting in cross-legged rows, little ones and bigger boys both – and there, standing in the wings, are the men who run this Home: normal men, in smart black robes; childsnatchers, every last one.

December is cold, but January is colder still. It snows only rarely, but when it does the city is draped in white and the frosts keep it that way, as if under a magic spell of sleep.

It is only in those deep lulls between snowfalls that the boys are permitted into the grounds of the Home. It is Peter who is most eager to venture out. Jon himself is plagued by a relentless daydream in which the Home has been severed from the terraces beyond. In the dream, the enchanted whiteness goes on and on, and he begins to wonder how his mother – not nearly so brave as his father – might ever find the courage to cross the tundra and find him. George, too, takes some coaxing. He has not been beyond the doors of the Home in long months and stands on the threshold, squinting at the sky. Peter assures him it is not going to cave in, but it does not sway George. It is only when Peter admits defeat and bounds outside, leaving him alone, that George finds the courage to follow. Watching Peter disappear into that whiteness, it seems, is the more terrifying prospect.

Some of the boys build forts; others attempt an igloo that promptly caves in and entombs a little one so that his fellows have to dig him out. The returned soldier leads a game of wars, in which each gang of boys must defend a corner of the grounds – but the game is deemed too invigorating by the elderly man in black, and must be stopped. Even so, the boys continue in secret. George, swaddled up so that he looks like a big ball of yarn, sits in a deep fox-hole dug into the snow, dutifully rolling balls for Peter to hurl, while Jon – a sergeant-at-arms – sneaks a little pebble into each one, to make sure it has an extra kick. In this way, they are able to hold their corner of the grounds, up near the gates by the fairytale forest, against the onslaught of a much bigger army. Peter declares it the most glorious last stand since Rorke’s Drift – but when Jon looks up to declare it better than Dunkirk, he sees that Peter is gone.

George is too busy rolling an extra big snowball, one they can spike with a dozen stones – Peter calls it the atom bomb – to see what Jon has seen, so Jon leaves him to his task and follows the trail of Peter’s prints. He has not gone far. He stands at the gates of the Home, with the stone inscription, now a glistening tablet of ice, arcing above. Icicles dangle from the ornate metalwork of the gate, and in places a perfect pane of ice has grown up.

Peter is simply standing there, squinting through the gate at the long track beyond.

‘Peter?’

Peter is still – but only for a moment. Then, he whips a look around and the expression on his face has changed. No longer does he look lost in thought; now he has a face ready for a challenge.

‘Do you dare me to do it?’

Jon’s eyes widen. ‘Dare you to do what?’

Peter tips his chin at the metalwork. Where the two gates meet there is a great latch, around which scales of ice have built up, like the hide of a winter dragon.

‘Go on, Jon Heather. Just tell me you dare it …’

Suddenly, the idea has taken hold of Jon as well. ‘OK,’ he says. ‘I dare you!’

Peter finds a stone under the trees and, taking it in his fist, hammers over and over at the ice. When the first shards splinter off, neither Peter nor Jon can stop themselves from beaming. A big chunk crashes to the ground, spraying them both full in the face, and they laugh, long and loud. Now, at last, the lock is free.

Peter stands back to admire his handiwork. He shakes his hand, trying to work some feeling back into his fingers.

‘Well,’ Jon says, ‘go on! That wasn’t the dare …’

With aplomb, Peter drops the rock, flexes his fingers, and takes hold of the latch. He moves to lift it, but the latch is still stuck. Still, not to be dissuaded, he tries again, each time straining harder, each time falling back.

‘You try,’ says Peter. ‘I can’t get a grip …’

But Jon Heather simply stands still and stares – and when Peter, nursing a frozen hand, asks him why, Jon just raises a finger and points. Unseen until now, above and below the latch there stand black panels with big keyholes set in each. Though they too are coated in ice, it is not the winter, Jon sees, that is keeping the boys entombed.

Something draws him to look over his shoulder. From a window high in the Home, surely in one of the barren rooms, the ghostly image of a man in black peers out. He has, Jon understands, been watching them all along, safe in the knowledge that they cannot escape. ‘Peter,’ he says, ‘we’d better get in.’

Before Peter can reply, a sudden cry goes up. When they look back, the little fox-hole around which they had been camping has been overrun. In the middle of a platoon of six- and seven-year olds, George sits dusted with the prints of a hundred snowballs, their atom bomb lying in pieces on his lap.

Jon sticks with them in those first weeks. When Peter is with them, the bigger boys in the dormitories leave them alone, and he and George are free to sit and push draughts across a chequered board, or make up epic games with the flaking lead soldiers that they find.

On the final day in January, they have ranged lead soldiers up in two confronting armies, when George asks about Jon’s mother once again. Jon does not want to hear it today. He has been counting down the days, and knows now that he is beyond halfway in this curious banishment.

‘Did she have short hair?’ George asks. ‘Or was it long?’

A ball arcs across the assembly hall, skittering through their tin soldiers to decimate Jon’s army and leave George victorious. From the other side of the hall, the hue and cry of the bigger boys goes up. Jon reaches out to pass back their ball, George scrutinizing it like it is some fallen meteorite, but he is too late. Out of nowhere, Peter lopes between them and scoops it up.

‘He asking you about your mother again, is he?’ Peter drops the ball and kicks it high. One of the other boys snatches it from the air and a ruckus begins. ‘George, I told you before. Don’t you make it any worse for him than it already is.’

‘I just want to know what she’s like.’

‘He shouldn’t be thinking about his mother. You remember how much time you spent thinking, and look where that got you.’

One of the other boys launches himself at the ball and sends it looping towards Peter – but Jon scrambles from the floor and punches it out of the air. ‘My mother’s nearly here,’ he begins. ‘Less than four weeks.’

‘Jon,’ Peter says, waving the other boys away, ‘I’m not saying it to be cruel.’ He turns, chases the ball, and disappears through the hall doors.

Sinking back to the ground, Jon gathers together the tin soldiers and begins to prop them back into their ranks. He is determinedly lining them up when George reaches out to pluck up a fallen comrade and stand him next to Jon’s captain. ‘If she does come back,’ he whispers, ‘I’d like to see her, just for a second.’

The snows subside as February trudges by, and the boys are released into the grounds on more and more occasions, so that soon it is simple for Jon to find some cranny where he can curl up and while the day away. Now, there is an eerie stillness in the Home, only the guardian men in black ghosting wordlessly around, sometimes hovering to watch their boys at play. The sun-tanned man in black is the worst, forever appearing in a doorway to prey on a boy with his eyes and then nodding sagely if a boy returns his gaze, as if, somehow, a secret pact has been arranged.

George has pestered Jon this morning for more games of lead soldiers, but Jon has concocted a plan. Peter may think he knows everything; he may think that, because he has lived for years among the men in black, he can never be wrong – but Jon knows his mother is returning. What’s more, he can prove it. He remembers the letter she pressed into his palm, that night she left him behind. In that letter, there is surely the proof that his rescue is imminent. He will find it and he will make Peter read every word – and, in only one week’s time, he will wave goodbye to Peter and George and never think of this Home ever again.

He waits at the head of the stairs as the men in black hustle a group of boys out into the pale winter sun. When all is still, he creeps down the stairs. The entrance hall is the centre of the Home, the chantry on one side, the dormitories circling above – with all of the other offices where the men in black live and work snaking off behind. It is along these forbidden passages, in that labyrinth of boarded and dead rooms, that he knows he will find the irrefutable truth that will be his sword and shield, words scribbled onto paper with a signature underneath.

He is about to set off when one of the men in black appears from the chantry. It is the man with leather skin, tanned by a sun that has barely shone since Jon was left here. His hair is piled high, his eyes deep and blue, and for a second they fix on Jon. Then, a voice hellos him from deep inside the chantry, and he turns. Jon seizes the opportunity and scuttles away.

He has never walked along this corridor before. It drops down unevenly and, on each side, there are chambers. He peers into the first and sees a stark room, as austere as the dormitories above. In the next, a black cowl hangs against a bare brick wall, bulging out so that, for a second, Jon believes a man might be hanging inside.

At the end of the corridor, a tall door looms, its panels carved with branches and vines. The door is heavy, but not locked. Inside, the chamber broadens from a narrow opening and winter light streams in. There are no beds here, only ornate chairs around a varnished table, and a thick burgundy rug covering the floor. Jon dares to step forward, his bare feet sinking into the shag.

He looks up. He marvels. Two of the walls are lined in books, but on the third wall, facing the windows so that its picture might be seen from the grounds outside, there hangs a great tapestry.

It is unlike anything he has seen. On the left, there stands the broadside of a ship, moored at a jetty with sailors hanging from the rigging, gangplanks thrown out – and there, on the deck, a single man in black with his arms open wide. Beneath him, the jetty is crowded with children, a cacophony of arms and legs all groping out to reach the ship. Among them, more men in black stand. They are not shepherding the children on, but each has his head thrown back, as if to send up a howl like a lonely, vagrant wolf.

As Jon looks right, the tapestry changes, its scale lurching from big to small. The children gathered on the jetty become a thin procession standing in the narrow streets of some cobbled city. Maidens in long white robes lounge over the rails of balconies above, their eyes streaming as they rain shredded flowers onto the heads below.

Further along, the tapestry reaches a strange apex, a trick of perspectives that makes Jon think he is looking at some terrible picture of hell. The procession of children seems to have changed direction, so that now they walk not towards the pier but away, along a steep mountain road. Through crags they come, descending the ledges to a wilderness of sand and stone. Men with dark skin and cloths wrapped around their heads peer at the procession. One, with a sword in each hand, lifts his weapons as if to shield himself from their glow.

Voices rise on the other side of the door.

Jon turns, but it is already too late. The door handle twitches, and the great oak panels shudder forward. Quickly, he tumbles towards the far side of the room. Nestled in the towering bookshelves there sits a hearth, but no flames flicker behind the grate. He forces himself into the fireplace. It is thick with soot, but he tucks his knees into his chin and braces himself against the chimneybreast. Then, as the door finally opens, he claws out to pull a fireguard in place. It is made of thin mesh, and he squints through so that he might see the men in black appear. At first, they are obscured by the table and chairs – but, finally, they move into the great bay window.

The older man moves forward with a cane in one hand, the other walking behind. Jon cannot be certain, but then the face appears in profile: it is the sun-tanned man. He reaches out to bring the old man a seat, passing the fireguard as he does so. Jon stifles a splutter; he has dislodged soot, and it billows around him.

‘It will be the last season you see me,’ the old man begins.

‘Father …’

The old man raises a hand only halfway. ‘I will not last another winter. An old man knows when his time has come.’ He pauses. ‘I am proud,’ he whispers, ‘to have seen it this far.’

They talk of all manner of things: the wars that have risen and fallen; the desperate families who have slipped through the cracks between the new world and the old. The old man remembers how it was the last time there was war, the great plagues that came afterwards like some punishment from on high. And now, he says, that hour has come again. A war might have ended, but the world has to limp lamely on. Across the country, the Homes of the Children’s Crusade swell – and throughout Britain’s once great Empire, the fields cry out for new hands.

‘Father,’ the sun-tanned man begins, glaring through the window at the endless white. ‘What will happen once you are gone?’

‘Why, the world will carry on turning.’

Something howls in the chimney, and instinctively Jon squirms. As he shifts, soot billows out of some depression and blots out everything else. His body convulses. He kicks out to brace himself against cold stone, but he cannot quite conquer the cough in his chest. When he splutters, his whole body pitches. The fireguard rattles in the hearth.

The voices stop. Jon gulps for air and slowly calms down – but there is no other nook in which to hide. He listens for the footfalls, sees the legs as they approach the fine mesh. He shrinks as the guard is lifted. The sun-tanned man crouches – and suddenly they are face to face.

‘Come out here, little thing.’

The man reaches out his hand. For a second, he holds the pose. Then, as if unable to refuse, Jon folds his own hand inside the massive palm.

In the shadow of the great tapestry, the sun-tanned man hauls Jon to his feet.

‘Is he one of them?’ he asks, dangling Jon by the arm so that the older man might see.

The elderly man nods.

‘Very well,’ says the sun-tanned man, and barrels Jon out of the room.

Behind Jon, a door slams. He reels against the wall and turns back just in time to hear a key turning in the lock. It is one of the cells he passed on his way to the library hall. There is little here but a bedstead with blankets folded underneath – and, high above, a single window glaring down. The branches of a skeletal willow tap at the glass.

He tries to sit, but he cannot stay still. He feels the urge to bury himself beneath one of the blankets, but he dares not unfold it. Instead, he parades the walls like a dog in its kennel.

There is scratching in the lock again, and the door judders open. The sun-tanned man does not say a word until the door is firmly closed behind him.

‘Jon,’ he begins. ‘You are fortunate it is me. Some of my brothers take less kindly to little boys busying themselves in places they should not go.’

In response, there is only Jon’s silence.

‘This,’ the man in black begins, reaching into his robe and producing a piece of folded paper. ‘Is this what you came for?’

Jon totters forward and takes hold of the letter. Once it is in his hands, he snatches it close to his chest and holds it there.

‘You may read it, Jon,’ the man says softly. ‘She told you not to – but what she says hardly means a thing anymore.’

Jon does not move. He knows what the man wants, knows that he desperately wants it too – but he will not tear open the letter while he is being watched. He holds the man’s glare until he can bear it no more.

Once he is alone, he crawls onto the naked bed. He turns the letter in his hands. It is almost time to read it – but he will savour it first.

Hours pass. He dreams of what he might find within: his mother’s sorrow at having to leave him behind, the dreams she has of the day he and his sisters will be reunited and the old house restored.

Darkness comes. It will be lights out in the dormitories above, but tonight there is moon enough to illuminate the cell.

He sits down and unfolds the paper.

It is not a letter, as he had thought. Instead, it is a form, typewritten with only two words inked in, and two more scrawled at its bottom: his name and his mother’s, the last time he will ever see her hand.

I, being the father, mother, guardian, person having the actual custody of the child named JON HEATHER hereby declare that I authorize the Society known as the Children’s Crusade and its Officers to exercise all the functions of guardians, including the power to house, home, command and castigate, and have carried out such medical and surgical treatment as may be considered necessary for the child’s welfare; including, thereafter, the right to license guardianship of the child to a third party proven in its dedication to the moral upbringing of young women and men.

There are words here that Jon does not understand, but he reads them over and over, as if by doing so he might drum their meaning into his head. He dwells even longer over her name scribbled below. It seems that by declaring her name she has performed some magic of her own; she is no longer his mother. He puts the paper down, retreats to the opposite corner of the room, goes back to it an hour later – but it always means the same thing.

His mother is never coming back; he is a son of the Children’s Crusade now.

The sun-tanned man’s name is Judah Reed. He brings Jon milk and bread for supper, and they sit in the silence of the chantry as Jon eats. On the side of the plate is a single apple, waxy and old but still sweet.

‘You have been selected,’ Judah Reed begins, ‘for a great adventure.’ He sets down a book and turns to the first page: black and white photographs inked in with bright colours, a group of young boys beaming out from the veranda of some wooden structure.

‘These boys,’ he begins, turning the book so that Jon can see the happy faces, ‘are the boys who once slept in the very same beds as you and your friends. Like you, they had no mothers, no fathers, no place to call their own.’

Jon bristles at the assertion, but his mother’s signature is scored onto the backs of his eyes.

‘They came to the Children’s Crusade desperate and destitute, but they left it with hope in their hearts.’

Judah Reed turns the page. There, two boys sit in the back of a wagon drawn by horses, grinning wildly as they careen through fields tall with grain. Behind them, herds of strange creatures gather on the prairie.

‘Where are they?’ Jon breathes.

‘They’re safe,’ Judah Reed continues, ‘and together, and loved. They work hard, but they have full plates every night – and, one day, every last one of these boys will own his own farm and have a family all of his own.’

Jon fixes him with wide, open eyes.

‘Have you heard of a land called Australia?’

In all the books Jon has seen, Australia is endless desert and kangaroos, convicts and cavemen. Of all the four corners of the world, it is the only place he has never imagined his father.

‘Those boys are in Australia …’

Jon reaches out and turns the page. A postcard of some sprawling red continent, surrounded by azure waters, is clipped into place. Judah Reed offers it to Jon. In the corner of the picture, a small grey bear holds up a placard that cries out a welcome. A little Union Jack ripples in the corner.

‘That’s where you’ve come from, isn’t it?’ Jon says, eyes darting. ‘You came to take us away …’

The man’s fingers dance on Jon’s shoulder. ‘You must understand, Jon, that this is what your mother wanted for you. Little boys grow up into wild, troubled men on these streets – men who lurk in the factories by day and torment the taprooms at night. There could be no other future for a boy like yourself, if you were to remain.’ For a fleeting second, Jon thinks he looks sad. ‘It does not have to be that way, Jon. There is a better life waiting for you. Your mother gifted you to the Children’s Crusade so that you might have just such a chance.’

The other boys, he goes on, have already been instructed. While Jon was locked away, they gathered in the chantry and heard the tale told. England groans with its dead – but its Empire is desperate for good souls to come and till its land, fish its lakes, conquer its wastelands. Australia is the Eden to which the orphaned boys of war are being summoned. It is not always that little boys, so full of malice and sin, are permitted back into the Garden. This is a chance, he explains, for Jon to begin again.

‘You don’t understand,’ Jon trembles. ‘I’m not supposed to be here.’

Judah Reed stands. ‘If you had not been locked away, Jon Heather, for trespassing against the very same men whose only purpose is to rescue you, you might have learnt about the noble traditions of the Children’s Crusade. How, many centuries ago, it was children who were called to do the Lord’s work in the Holy Lands. And how their time has come again – how children, brave and unsullied, are to crusade to the other end of the earth, where the Empire will surely die without us …’

Jon does not care about the British Empire; he cares only about his empire – his mother, his sisters, red bricks and grey slates and the terrace rolling on and on. ‘But I want to stay,’ he ventures.

‘You will find that the new world welcomes you,’ says Judah Reed, striding to the chantry doors and stepping beyond. ‘I’m afraid, Jon Heather, that the old world doesn’t want you anymore.’

‘Jon!’ George tumbles out of bed as Jon steals back into the dormitory. ‘Jon, where have you been?’

It is dark in the dormitory, but moonlight glides across the room as, somewhere above, snow clouds shift and come apart.

‘Get back into bed, George.’ Peter swings out of his bunk, biting back at some snipe from one of the bigger boys lounging above. He goes to George’s side and, an arm around his shoulder, ushers him back to his cot.

‘But I just want to …’

‘Jon doesn’t want to hear it,’ Peter whispers. ‘Not now.’

As Peter is tucking the sheets in around George, batting back his every question, Jon trudges the length of the dormitory and finds his own crib. It is just as he had expected: the blankets are gone and only the pillow remains.

‘Jon, what did they say?’

Peter lopes out of the shadows, rests his foot on the base of Jon’s bed. Sitting at its head, Jon realizes he is still kneading the postcard. It is creased now, and the ink has smeared his fingers.

He offers it up. When Peter takes it, he cannot make it out – but, nevertheless, he seems to know.

‘They took us in the chantry and sat us down. They say it’s a paradise, waiting for boys like us, fresh fruit for breakfast and crystal lakes full of fish – that we’ll all grow up to have big ranches and families and everything boys could ever want.’ He pauses. ‘Jon, there’s something else, isn’t there? What did Judah Reed say?’

From down the row, someone barks at them to shut up. Peter lets loose with a volley of his own, and the silence resumes.

‘He said we were being rescued,’ Jon begins. ‘But – but I don’t need to be rescued, Peter.’

Peter relaxes, sits beside Jon.

‘I know what you’re going to say, Peter. But I saw her letter. He made me read it. And …’ He takes the pillow into his lap and beats it. ‘There’s still my father. It will all be OK when my father finally comes home. But if I’m not here, he’ll never find me. I’m not like you, Peter. I’m not like George. I’ve got …’ He trembles before saying it, but he says it all the same. ‘… people who love me.’

Peter stands. ‘There’s every one of us in here just like you,’ he says. ‘Every one of us had a mother and a father who didn’t come back.’ He turns, kicks along the row to find his bunk. ‘We’re the same in this hole,’ he mutters, ‘and we’ll be the same on the other side of the world.’

Peter slopes back into the shadows, but Jon is not ready to let him go. Leaping up, he screws up the postcard and hurls it after the retreating silhouette. ‘You want to go!’ he thunders. ‘You’re happy to be going!’

The silhouette hunches its shoulders and turns around.

‘Peter?’ comes a voice.

‘You go to sleep, George,’ Peter whispers. He stalks back up to Jon, lands a heavy hand on his shoulder. ‘You upset him over this, and I’ll throw you overboard the first chance I get. I’m not happy, Jon, and I’m not sad. This place or some other place – it just doesn’t matter to me anymore.’ There is fight left in Jon, but suddenly he softens; his shoulders sink and he tries to squirm back. ‘There isn’t any escaping from it. We were marked for it the second we came through those doors.’

Jon curls up on his bare mattress and reaches into the slats for his beloved book. It is too dark to make out any of the words, but it doesn’t matter – he knows it by heart. In the story, a gang of friends drift out to sea aboard the old Goblin and land, at last, on some foreign shore. There, among the alien faces, is the one they clamour for: their errant father, who takes them safely back home. Jon flicks quickly to those pages – as if, even in this darkness, he might breathe it in.

Something shudders at the end of his bed, and he reaches out to see a blanket suddenly lying there. On the other side of the dormitory, Peter slumps onto his bed and pulls an overcoat around him with a grunt.

‘Thank you,’ Jon whispers – but there is no reply.

Jon does not sleep that night. He lies awake, listening to the fitful snores of the other boys. In the small hours, he suddenly remembers the great brick arch through which he first entered the home, the stone inscription that was hanging overhead. At last, he understands what it means.

It is as the boys of the Home have always understood: the childsnatcher does not come in the dead of the night. He does not creep upon the stairs. He does not lurk beneath the bed, clutching a sack in which to stash all the little boys he carries away. He comes, instead, in a smart black suit, with a briefcase at his side and papers in his pocket. He crouches down and calls you by your name – and, once you take his hand in your own, you will never see England again.

III

They set out from a dock in Liverpool. It is as far from home as Jon has ever been, but now even this foreign city dwindles on the horizon, lost in mist from the sea.

They call it the HMS Othello. It has ploughed through countless wars, but now it is bound to a different journey. Below deck, the boys sleep three to a cabin. After the dormitory, it is a luxury to which none of the boys are accustomed.

After lights out on the first night, there comes a gentle rat-a-tat at the cabin door. Peter swings out of bed and whips the portal open. Still clinging to the cardboard suitcase they have each been issued with, there stands George.

‘Can I sleep in here, Peter?’

There are three bunks in the cabin, Jon curled up in one, no doubt pretending to sleep; some other boy in the other. Peter shakes him until he stirs. ‘Hop it, Harry,’ he says. ‘We need the bed.’

Muttering some incomprehensible complaint, the boy trudges out of the room.

As he goes, George creeps through the door and finds the bunk warm and inviting. ‘Thanks Peter.’

‘Don’t thank me,’ Peter says. ‘Just go to sleep.’

There is only a moment’s silence. Between them, Jon hears George begin to speak. Then, thinking better of it, he holds his tongue. Two more times he tries to be still, but it will not last long.

‘What is it, George?’

‘I didn’t like the way the ship was moving. It feels like we could tip right over.’

Jon hears Peter’s sharp intake of breath, decides Peter is about to admonish George, and scrambles upright in bed. ‘I don’t like it either …’

‘You can hardly walk,’ George goes on. ‘One minute you’re in the middle of the hall, the next you’re up against the wall. Nothing looks right.’

Peter rolls over, drawing the bedsheets over his head.

‘It’s only Judah Reed can walk without stumbling,’ George says. ‘Why can Judah Reed walk like that, Peter?’

There comes another rat-a-tat at the door. George instinctively shrinks into his covers, while Jon dives back into bed. Only when he hears Peter pulling the door back does he open an eye to watch.

There are two boys standing in the doorway. The smaller, Harry, is still trailing his blanket; a taller boy looms above.

‘We don’t want this one in our bunk, Peter. Some of us want to sleep. There’s enough little ones down the way, without throwing this one in with us.’

Peter throws a look back at George, now nothing but a bundle beneath the bedclothes.

‘If we let you sleep in here, you’ll sleep on the floor?’

Harry nods, eager as a dog waiting for its bone.

‘You can take a pillow,’ Peter adds. ‘But it’ll take Judah Reed to stop me pounding on you if you piss everywhere tonight.’

Peter slumps back into his bunk, rucking up his blankets to make up for his missing pillow, and snuffs the light. Moments later, George bleats out. At first, Peter thinks he is being a scaredy-cat yet again – but, when he tugs at the cord, he sees George sitting up in bed with wide, apologetic eyes.

‘It’s no good, Peter,’ he says. ‘Just the mention of it makes me want to …’

‘What the hell,’ Peter mutters. ‘I wasn’t going to sleep tonight anyway …’

Jon follows them out of the cabin, leaving the fourth boy to crawl, eagerly, into one of their beds. The corridor outside is narrow, lit by buzzing electric lanterns. The ship is a labyrinth, but Peter seems to know his way better than most. Jon and George trail after him like rats behind some piper.

They are not the only boys on board. There are others, boys in prim school uniforms – and, so the whisperers would have it, girls in smart pinafore dresses too. Nor are Judah Reed and the other men in black the only adults travelling south. Jon has already seen a group of swarthy men, speaking in some guttural language of their own.

Peter leads George up a small flight of wooden stairs, and fumbles with a clasp to kick open the portal above. When the doors fly open, sea spray whips at George’s face.

‘Isn’t there another way, Peter?’

‘I don’t know, George …’

‘I don’t think I can go overboard, Peter.’

They venture up. There are still adults milling about the deck, keeping windward of the great hall that sits there.

Jon closes the trapdoor and, hand in hand, they scuttle towards the great hall. Creeping downwind of it, they search for the way in. The boys have never seen luxury like this: waiters are pushing trolleys, men with skin as dark as those who came to live in Leeds, while a chandelier dangles above. At last, they find an unlocked door and push inside. From here, Peter remembers the route. He leaves George at the toilet doors, and tells him to hurry.

‘He’ll only be at pissing again by the time we get back,’ Peter whispers. ‘That boy could not drink a drop for three days and still find water to piss.’

When George reappears, he is shaking. As they go back on the deck, the ship rises up on a deep wave and then rolls. Hanging lanterns throw light onto George’s face, and Jon sees that he has been sick.

‘Wipe it off,’ says Peter, slapping him on the back. ‘You’ll get used to it.’

‘I’m feeling it too,’ says Jon.

‘Yeah, well, don’t you two go turning it into a competition …’

Peter pauses. He has been denying it to himself, but even he can feel a sickly stirring in the pit of his stomach. He looks up. The half-moon, beached there in white cloud, is the only thing that doesn’t seem to be trembling in the whole wide world. ‘You see that?’ he says, putting an arm around George’s shoulder. ‘Even the moon’s closer than Leeds is now. At least we can still see the moon.’

‘It’s the same moon, though, isn’t it, Peter?’ George marvels, as if he has uncovered some unfathomable secret. ‘And the stars – they’re the same stars?’

Peter turns and strides towards the edge of the ship. The starlight sparkles in the water, so that it seems there are silvery orbs bobbing just beneath the surface.

‘I wouldn’t swear on it,’ he says.

The seas are rough that night. In his bunk, Jon cannot sleep. When he scrunches up his eyes, he can almost pretend that the cabin is not rolling with the waves – but then the lump starts forming in the back of his throat, and then he has to curl up like a baby to stop himself from throwing up. In the bed beside him, George has retched himself into uneasy unconsciousness while, beyond that, Peter gives a fitful snore.

Some time in the smallest hours, there comes a lull, as if the sea has flattened out to allow him some rest – but, cruelly, Jon is no longer tired. Careful not to tread on the younger boy Harry, he stands up and creeps to the door. As he steps out, the corridor pitches and lanterns throw long, dancing shadows on the wall.

The belly of the boat moans, long and mournful, but when the sound dies down, he can hear something else: another whimpering, not of the boat, but of a boy. Steadying himself with a palm against each wall, he shuffles along the corridor, until he finds a cabin door left ajar. With each wave, the door opens inches and then closes again, allowing Jon to peep within. In one bed, a bigger boy has his head buried under a pillow while, on another, a much younger boy, perhaps only four years old, has his sheets pulled up around him.

Jon curls his fingers around the edge of the door, stopping it from swinging, and suddenly the boy’s eyes shoot at him.

‘What happened?’ Jon whispers.

The little one will not answer, but suddenly the bigger boy rears from his pillow and lets loose an exasperated groan. ‘Get it to shut up, would you? It’s keeping me up with its wailing …’

‘Is he hurt?’

‘Judah Reed came round,’ the bigger boy says. ‘Told him his mother’s kicked it.’

Jon opens his mouth but does not have any words.

‘Don’t know why he’s making such a fuss. He got a piece of cooking chocolate out of it. More than I got when they broke it to me. I got a pat on the head.’

The little boy lets out another cry but, when Jon goes to him, he only buries himself in his sheets.

Sitting on the end of his bed, Jon hears footsteps outside, and looks up to see Judah Reed himself standing in the open door.

‘I believe this is not your cabin,’ he says. The ship suddenly lifts, but in the passageway Judah Reed does not even stagger. ‘Well?’

Jon nods, swings down, and makes to leave. In the doorway, he has to squeeze past Judah Reed himself. He smells of honey and charcoal soap.

‘What happened to his mother?’ Jon asks, remembering his own, the way she held his hands as she passed him the letter and took off up the road.

Judah Reed’s blue eyes look immeasurably sad. ‘I believe she was … consumptive,’ he says, and steers Jon on his way.

In the morning, the waters have changed, reflecting the pale blue vaults overhead. Around them, the ocean glitters. There are landmasses on the horizon, hulks of earth gliding in and out of view. As Peter leads George and Jon onto the highest deck, they dare not look out at the vast oceans that stretch into the west, gathering instead at the port side of the ship and pointing out proud headlands and outcrops of rock.

Jon tells them about the boy from last night. He was not, it seems, the only one. Last night, Judah Reed stalked the passageways below deck, leading boys off to some office deep in the belly of the boat, palming a hunk of chocolate or toffee into their hands and telling them: your mother is dead; your father is gone; you’re our little one now, and we won’t do you wrong. It was, one of Peter’s friends tells them, like a nursery rhyme, one they then had to repeat: my mother is dead; my father is gone; I’m your little one now, and you won’t do me wrong.

In a launch at the stern of the ship, they find lifeboats, each stacked on top of the other. Finding a way into the first is simple enough – all they have to do is crawl under a lip of wood and work their way beneath a stretch of tarpaulin – but it does not feel the same as Jon thought it would. Sitting in the prow of the boat, with an oar latched either side, it does not feel like escape. He hears George approaching, crawling on hands and knees, and Peter following after, straining to contort his bigger body through the gap. He only has to look at George’s face, breaking into a beam, to understand: like everything else that they share, this is just make-believe. He could spin a story of stealing this lifeboat and rowing back to England to find his sisters and wait again for his father, but that is all it would be – a fairy story to delight the fat boy.

‘What is it, Jon?’

George is trying to pluck one of the oars from its clasps.

‘Do you think Judah Reed’s finished telling boys their mothers have died?’ he asks, looking over George’s head to where Peter crouches.

‘I don’t know …’

‘Only, why did he tell them when they got on board? Why not back in the Home, like he did for George?’

Suddenly, George remembers. His hands stop prying at the oar, and he shoves them in his pockets. ‘I didn’t even get a hunk of chocolate.’

‘He’d have come for me last night, wouldn’t he, Peter?’ Jon’s voice rises helplessly. ‘If she really was …’

He does not have to finish the words. Peter nods, but it does not convince.

‘What happened to your mother, Peter?’

Now even Peter has his hands shoved in his pockets. ‘You don’t want to hear that silly old story,’ he says, shuffling from foot to foot. ‘Does he, George? He doesn’t want to hear that dreary old thing.’

‘I like your stories, Peter.’

Now they look expectantly at Peter, as if waiting for a bedtime tale.

‘My sister, Rebekkah, she reckoned it was a broken heart. On account of the fact my father didn’t come back. Dead in India, they said, but he wasn’t even fighting. He was on a motorbike and it flipped. He used to ride one even before the war, and my mother always hated it. She said I went on it once, but I don’t remember. Then there’s a letter in the post and it says he was killed in action, but it wasn’t really action and it wasn’t really killed. It was just an accident, and my mother wasn’t the same after that.’

‘So she kicked the bucket!’ chirps George.

Peter doesn’t mind; he simply nods. ‘Sometimes that’s all it is, I suppose. There one day, gone the next. So Rebekkah and me, we tried to muddle through, but there was a neighbour who kept coming round with bits from her rations, and eventually she cottoned on. Rebekkah begged and begged, but it didn’t work. They sent a man with a briefcase, and then we had to put some things in a bag. I thought we were going to be together, but they sent Rebekkah to a place for girls, somewhere called Stockport.’ Peter pauses. He is hanging his head, so that Jon can barely make out his face. ‘So then that’s it. Children’s Crusade and …’

‘How long?’ whispers Jon.

Peter shrugs, but it is a pretend shrug, as if there is something he wants to hide. ‘I can’t remember. Four years, I suppose … five months. A few days.’ He hesitates. ‘Nine days. You want the minutes and hours as well?’

There is a gentle pattering on the tarpaulin, rain beginning to fall across the ocean. Soon, outside, Jon hears the scampering of feet as people head for shelter.

‘Peter,’ says George. ‘I feel sick again.’

‘The ship’s hardly moving, George.’

‘It’s not the ship. It’s my insides. They’re turning somersaults.’

When they emerge, the decks are almost empty, every man, boy and girl heading for their cabins. The rain now comes in sporadic bursts. Jon looks up. He wonders: was it a storm like this that waylaid my father? Is that why they really put me to sea? Or is it something worse?

‘What if my mother didn’t come for me because …’ His voice trails off – for, along the length of the ship, towards the prow, he has seen the spindly black figure of Judah Reed, crouching above a collection of little ones.

Jon reaches out, as if to take Peter’s hand. He does not know he is doing it until it is too late. Peter shakes him off, gives him a furrowed look.

‘Come on,’ says Jon.

If Judah Reed cannot catch him, he cannot tell him his mother has died. If it is true, Jon does not want to know. Quickly, he takes off, lifting the door back into the bowels of the boat.

Peter and George hurry after.

‘Where are we going?’ George puffs.

Jon Heather thinks: somewhere they can’t find me.

Soon, in the depths of the ship, they are hopelessly lost. Peter demands that they stop as he paces a passageway, trying to get his bearings. Jon swears that he could find the way back to deck simply by listening to the creaking of the ship, but the doubt in his voice is all too plain, and suddenly George starts to blubber. A sharp slap on the back quells him, but after that he waddles nervously in Peter’s wake, complaining of being hungry and thirsty and afraid of the dark.

‘Can you be shipwrecked if the ship isn’t wrecked, Peter? What if we get shipwrecked down here?’