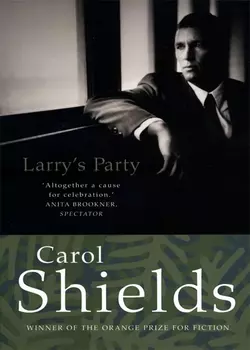

Larry’s Party

Carol Shields

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 232.65 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The Orange Prize-winning novel of Larry Weller, a man who discovers the passion of his life in the ordered riotousness of Hampton Court’s Maze.Larry and his naive young wife, Dorrie, spend their honeymoon in England. At Hampton Court Larry discovers a new passion. Perhaps his ever-growing obsession with mazes may help him find a way through the bewilderment deepening about him as – through twenty years and two failed marriages – he endeavours to understand his own needs. And those of friends, parents, lovers, a growing son.