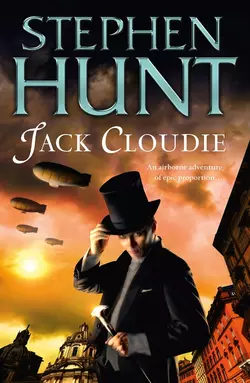

Jack Cloudie

Stephen Hunt

A tale of high adventure and derring-do set in the same Victorian-style world as the acclaimed The Court of the Air and The Secrets of the Fire Sea.Thanks to his father's gambling debts, young Jack Keats finds himself on the streets and trying to survive as a pickpocket, desperate to graft enough coins to keep him and his two younger brothers fed.Following a daring bank robbery gone badly awry, Jack narrowly escapes the scaffold, only to be pressed into Royal Aerostatical Navy. Assigned to the most useless airship in the fleet, serving under a captain who is most probably mad, Jack seems to be bound for almost certain death in the far-away deserts of Cassarabia.Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, Omar ibn Barir, the slave of a rich merchant lord finds his life turned upside down when his master's religious sect is banned. Unexpectedly freed, he survives the destruction of his home to enter into the service of the Caliph's military forces – just as war is brewing.Two very similar young men prepare to face each other across a senseless field of war. But is Omar the enemy, or is Jack's true nemesis the sickness at the heart of the Caliph's court? A cult that hides the deadly secret to the origins of the gas being used to float Cassarabia's new aerial navy.If Jack and his shipmates can discover what Cassarabia's aggressive new regime is trying to conceal, he might survive the most horrific of wars and clear his family's name. If not…

Stephen Hunt

Jack Cloudie

Contents

Epigraph

Chapter One

Jack Keats was pushed aside by the others in the…

Chapter Two

There was only one upside to being a slave, Omar…

Chapter Three

Jack stumbled to the rail at the front of the…

Chapter Four

Jack didn’t know the name of the airship field the…

Chapter Five

Omar ran through the great house’s central garden. Everywhere there…

Chapter Six

‘Help me,’ begged the six-year-old stuck down the claustrophobically tight…

Chapter Seven

‘Where is your mind today?’ demanded the cadet master, cutting…

Chapter Eight

Jack watched First Lieutenant Westwick walk across to where he…

Chapter Nine

Omar returned to the palace. There was a chiming noise…

Chapter Ten

Standing in the corridor that led to the great library…

Chapter Eleven

Jack rubbed his brow, half covered by a turban and…

Chapter Twelve

The grand vizier angrily sent a goblet spinning across the…

Chapter Thirteen

Captain Jericho leafed through the ship’s dispositions in his cabin…

Chapter Fourteen

Omar dodged aside as a miniature beyrog-like monster slashed at…

Chapter Fifteen

Jack was helped to his feet by Lieutenant McGillivray, the…

Chapter Sixteen

‘Heaven’s teeth, can’t you do this any quicker?’ asked the…

Chapter Seventeen

There were shouts verging on panic from the spotters on…

Chapter Eighteen

Omar was running through the Citadel of Flowers’ oppressive halls…

Chapter Nineteen

Omar winced as the gaggle of the citadel’s surgeons and…

Epilogue

‘Now then, laddies,’ said the gruff lieutenant on the desk…

About the Author

Other Books by Stephen Hunt

Copyright

About the Publisher

If you can smell the scent of death on the air and you do not know where the smell is coming from, then the smell is coming from you.

Ancient Cassarabian proverb

CHAPTER ONE

Middlesteel, the Kingdom of Jackals’ capital city

Jack Keats was pushed aside by the others in the gang as the shout echoed out from the shaft in the wall. They were deep in the bowels of Lords Bank, having broken in through the sewers. But even so, if the boy kept yelling like that, one of the bank’s night watchmen would hear the racket and then every member of the young gang would be done for.

‘I told you it was a mistake bringing the boy,’ said Jack. ‘He’s too young.’

‘Shut your cake-hole,’ snarled Boyd. It was hard to tell whether the gang’s leader was snapping at Jack for questioning his authority, or venting his aggression towards the boy crawling deep into the shaft running alongside Lords Bank’s main vault. Boyd leant into the dark shaft, looking in vain for any sign of the small boy’s flickering gas lantern.

‘He’s scared down there,’ said Jack. And of course, my fingers aren’t trembling from fear. That’s just the cold.

‘He should be more scared of me,’ spat Boyd, bunching his fist in anger before turning on Jack. ‘Yeah, and you’ve got two brothers his age locked up in the sponging house. And that’s where they’ll stay unless we get inside this vault. So you think of your kin, not ’im down there.’

‘The workhouse,’ said Jack. You ignorant fathead. ‘They’re in the workhouse now, not the debtors’ prison.’

The five others standing behind the gang chief sniggered at the distinction and Jack’s superior tone of voice, all of them grimy and dust-covered from breaking through the brick foundations of the sewer to get this far. Maggie was with them and she gave him a despairing look – the kind that said this was not a good time to be wearing his education on his sleeve. She had shown him the ropes of street life in more ways than one. Eating stone-hard bread in a debtors’ prison and broken by the family debts, or washing down the same rations with the gravy water that passed for soup in the workhouse. Any difference between the two was paper-thin, and Maggie knew it.

‘Well, pardon me,’ laughed Boyd. ‘You’re not the son of a gentleman farmer down ’ere. You’re shit, just like us. On the job, on the make.’ Boyd pointed down the shaft towards the young boy. ‘He’s small, useful shit. You’re clever shit, and I need your fingers, so don’t give me no excuse to break some of ’em for you.’

Jack guessed this wasn’t the time to point out the meaning of a double negative to the hulking thug. ‘And what about you, Boyd?’

‘I’m the biggest shit of ’em all, Cracker Jack. I dream up the juicy jobs; I saw how your clever fingers might drag us all out of the gutter. After we pull off this job we’ll dress like swells and eat like lords from the best the city’s got to offer.’

Jack stared into the dark shaft where the boy was coughing. But only if their little shaft rat found the vault’s timing mechanism and managed to jam it, only if he held his nerve and kept the special tool Jack had forged wedged into the machinery for long enough. And only if Jack was every bit as good as he believed himself to be.

‘Talk to the runt,’ Boyd ordered Maggie. ‘Steady his nerves.’

Maggie moved to the hole and started whispering and cajoling. She was as much a mother as most of the young street children and pickpockets in the slums behind Sungate had known, although she was barely an adult herself. Her pleas and support must have had the desired effect, though, because Jack heard the cogs of the transaction-engine lock they had just exposed snap into place. It had shifted from its nighttime lockdown mode to its daytime setting, and that meant the vault could now be opened. Provided you bore the two golden punch cards of the chief cashier and chief clerk of Lords Bank, inserted in unison. Or, failing that, if you possessed a talent for opening such things.

The others in the group watched in quiet reverence as Jack dipped inside the toolbox he had lugged through the dark, stinking sewers, and began picking away at the exposed mechanism of the vault’s steam-driven thinking machine, taking readings from the symbols along the bank of slowly rotating drums. It took twenty anxious minutes to re-jig the punch-card reader to accept his input, but the physical work was in many ways the simplest part of this crime – pure mechanics, that any engineman skilled enough could undertake. But the next part of the job was one only the most talented cardsharp would be able to carry off. Jack would have to match his brain against the thick layers of cipher and code that lay between him and a series of steel bolts as large as his legs, persuading them to withdraw and admit the gang into the vault … into a whole new existence. Let me be good enough. Sweet Circle, let me get this one thing right. Just for today, let me be good enough.

‘That’s it, boy,’ muttered Boyd behind Jack, in what the ruffian probably mistook for encouragement rather than distraction. ‘You do this and you’ll be able to buy your two runts out of the poorhouse. You’ll be able to complete your training with the Brotherhood of Enginemen – hell, you could buy a seat on the guild’s council.’

Jack grimaced at the delinquent’s meagre conception of his life before his father’s debts had seen his family incarcerated. What comfort, to be appreciated by you, you simple-minded thug, but nobody else. This is what I’ve sunk to. Jack didn’t need to finish his guild training; he had already moved far beyond that. What he needed now was to buy his way into sitting the examinations and pay for his apprenticeship papers. Without that, no mill owner or dusty office of clerks was going to allow him within a thousand yards of any engineman’s position. A closed shop, like so many of the skilled trades.

‘Quiet,’ hissed Jack.

‘I’ve seen you do this a dozen times.’

‘Not like this.’ He brushed his dark hair out of his eyes. ‘This isn’t a lock on a jeweller’s shop or some merchant’s townhouse. This is a strong cipher, written by people who knew what they were doing. Proper cardsharps.’

Yes, the sort who were only too glad to turn him away from every job he had begged for, a ragamuffin without guild papers. Unwanted competition.

‘Please, Jack.’ Maggie’s voice sounded from next to the shaft. ‘Quickly. I can hear little Tozer down there. He’s crying.’

‘Button it up, runt,’ Boyd hissed down the shaft. ‘You keep your hand stuck in the timer as long as we need it there.’

Boyd could smell the money now, he could taste it. And the Circle knew, Jack had seen Boyd like this before. His shoulders started rolling from side to side, as if he was balancing the weight of all the mouths that needed feeding among his little mob. Boyd was always dangerous during such times. Pity the maid-of-all-works who stumbled across him rifling through her mistress’s cabinet when he had a necklace in one hand and a blade in the other.

Jack turned his attention back to the transaction engine, his clever fingers going about their work. Whatever puppy fat there had been on those fingers had disappeared years ago. He was bony now. Thin and desperate. There wasn’t a mirror in the derelict rookery apartment that Jack and the others called home, but he knew what he would see if he looked in one now. Street eyes. The trusting innocence of youth replaced by the narrow, darting glance of the slums. Old man’s eyes in a face too young for them. They were the same eyes he looked into when he saw his two brothers during the weekly visiting hour at the workhouse. Poor little Alan and Saul. Half his age, but they already had those eyes. Unless Jack could steal a different life for them. Buy time enough to forget the images of their father coughing his last breath away inside the damp confines of the sponging house. Am I any better than father was? I thought that after his death saw our family discharged from the debtors’ prison, I would be able to get a job – begin a new life, a new start. How little did I know. It was my failure that saw my brothers end up in the workhouse, my mistakes, not father’s. Trading the sponging house for the poorhouse, one low class of prison for another.

Jack had the measure of the cipher now: he held it in his mind, still twisting and turning on the engine’s drums, as he removed the little portable punch-card writer from his sack. He began to stitch a series of holes in the first of the blank punch cards that had been stolen to order for him. No one else could keep their decryption routines so short, not an ounce of wasted code. Jack’s key was done within five cards. Feeding them into the exposed injection reader, he heard ten seconds of clanking and clunking in answer from the depths of the engine, and then the massive vault door slowly began to inch upwards, revealing the first glimpse of what lay within. A chamber as big as a Circlist church hall, steel walls marked with thousands of deposit-box drawers and a metal floor crisscrossed by waist-high bins filled with notes and coin of the realm. Lords Bank was the richest counting house in the country, patronized by the wealthiest industrialists, merchants and landowners in the Kingdom, and here their wealth stood revealed, inch by slow inch; until the door stopped opening, squealing rollers matched by a scream from the shaft.

Jack’s eyes darted to the drum’s new configuration, the icons of symbolic logic lining up in a fierce new pattern. ‘The vault’s shifted back to nighttime mode.’

‘You little runt!’ Boyd yelled down the shaft.

‘I dropped the tool out of the timer,’ the boy’s trembling voice came back, ‘just for a second, that’s all.’

There was the distant sound of alarms on the many floors above them, the guards and watchmen no doubt rousing as the late-night peace of their marble temple to money was rudely shattered.

Boyd smashed his fist in fury against the stalled vault door, a thin strip of the paradise snatched away from him still teasingly visible. ‘My fortune. My bleeding fortune.’

One of the young thugs dragged the gang’s leader back, pointing up at iron tubes pushing out of the ceiling. ‘Dirt gas. Got to go!’

‘Tozer,’ Maggie yelled into the black square of the shaft entrance. ‘We have to pull him out.’

Boyd shook his head, roughly shoving the rest of the gang back in the direction of the bank’s breeched wall and the sewer tunnels.

‘He’ll suffocate down there before he climbs out,’ said Jack.

Boyd seized Maggie’s arm and pulled her away from the shaft. ‘You stay then, Cracker Jack. See if you’re clever enough to breathe dirt gas.’

Jack’s head turned, hearing both the whimper of the six-year-old thief and the distant gurgle of liquid gas passing down the pipes above him, already reacting with the air and turning into sweet, deadly, choking smoke.

No time. He’s as good as dead down there. I’ve failed him too, just like I always do my family.

‘Never was any good lifting wallets either,’ said Boyd, nodding in satisfaction as he saw that Jack had decided to cut and run like the rest of them. Clever hands like Jack’s were hard to find in the slums.

Jack tried to ignore the echoing screams that followed him out into the sewers. Coward, I’m a useless coward.

The agonizing sound finally died as the gang turned into the light from the constabulary’s bull’s-eye lanterns. Then the shouts of uniformed brutes wielding police cutlasses and heavy pistols charging down the sewer tunnel were all that the hungry young thief could hear.

CHAPTER TWO

The Empire of Cassarabia – Haffa Township

There was only one upside to being a slave, Omar considered, from his vantage point on top of the desalination tank. Why, if he had been born a freeman like Alim, he too might be wearing a perpetual frown of worry across his face all the time. Freemen in Cassarabia always had something to worry about, it seemed. Politics. Religion. Trade. The weather. Alim was probably worrying why the salt-fish in the tank below Omar weren’t being released into the next tank down the line, ready to go about their profitable business of separating the salt out of the sea water, leaving pure clean drinking water behind them, before disgorging pellets of table salt onto the beds of the third tank lined up under the shade of the water farm.

But nobody expected initiative from a slave. Indeed, it was very carefully beaten out of them. Omar had been ordered to scrape the salt residue out of one of the drained tanks, readying it for a new batch of salt-fish. Omar hadn’t been instructed to then open the lock gates and set the desalination process in motion again. A freeman would care about having fresh drinking water to sell at market. A freeman could have their wages docked. But a slave? Slaves weren’t encouraged to show their initiative, for such an attitude led to escape attempts across the desert.

‘Omar Ibn Barir,’ shouted Alim, spotting the young man lazing on top of the water tanks. ‘Do you expect the water farm to run itself?’

Well, miracles do happen, master. But failing that, how about you just shout at me until I do it for you?

Omar pushed himself up and off the water tank. He could always tell when Alim was annoyed with him, because he used his full name. The ibn to indicate he was property, and the house-line of Barir to indicate where all his devotion should rightly be directed. ‘I was resting, Master Alim. Saving my strength for my next duty.’ He indicated the parallel run of desalination tanks in front of them. ‘Have you ever seen the bottom of a filter tank scrubbed so clean of salt? There are chefs in the souks of Bladetenbul who will say twenty prayers of thanks to the one true god that there was a boy called Omar so diligent that the sacks of salt they buy from us are as plump as a caravan master’s belly.’

‘It is you who should say twenty prayers,’ said Alim, ‘for being so fortunate as to be born a slave into the house of Marid Barir, for no other master would spare you the floggings you so richly deserve.’

Omar did not risk the old man’s ire by noting that few other civilized masters would have employed a grizzled freeman like Alim, either, his rough nomad manners barely softened by the decade he had spent inside the town of Haffa. Bred a slave, Omar counted the russet-faced Alim as much a father as he had known in his young life. The only male company he was familiar with, the only man he had worked alongside for years. Such as it could be divined, the good opinion of Alim mattered to Omar. Often he was gruff, but when the old nomad could be roused to humour, his laugh would explode like a thunderstorm, his body shaking and jolting almost uncontrollably under the shade of the water farm. Omar had noticed the old tribesman seemed to find less to laugh about these days.

Alim looked up at the tank where Omar had been lounging. ‘A fine view of the caravan road.’

‘There is no sign of the water traders yet,’ said Omar.

‘It is not water traders, I think, that you were looking for.’

Omar tried not to blush, affecting an air of nonchalance, as if he had no idea what Alim was inferring.

‘Shadisa will not come by today,’ said the old nomad. ‘She has gone down to the docks to inspect the fishermen’s afternoon catch for the great master’s table.’

Omar shrugged, as though the news made no difference to him.

‘Ah, Omar,’ sighed Alim. ‘If you were a comely female and she the son of a freeman, rather than a daughter, you might have a chance. But what fortune or alliance does a male slave bring to an honourable family? The stench of salt-fish and the fifty altun it would cost to purchase your papers of ownership from Marid Barir?’

‘My smell is not so bad.’ And I am born for more than this, you grumpy old goat. I can feel my greatness like the burning fingers of the sun, trembling and ablaze within me. A pity you do not see it.

‘You have worked here so long that you have lost your sense of it,’ said Alim.

‘Whatever my smell, Alim, you cannot fail to admit that I am handsome. When I catch my reflection sometimes, I believe that the one true god must have sent an angel from heaven to bless my cradle.’

‘He sent something, boy. A lazy joker to swell my workload here.’

In one matter the old nomad was correct, Shadisa would not come by today. Omar knew. There had always been a connection between the two of them. He could sense when she was coming or when she was near. Sometimes when he was in the great house of their master, he would imagine she was in a certain part of the house and if he ventured close to there, he would find that his sixth sense was proved correct. Old Alim had laughed when Omar told him about this ability. There were men whose bodies had been twisted by womb mages who had such abilities, the nomad had explained, scouts in the elite regiments of the caliph’s army – units such as the imperial guardsmen – the cutting edge of the caliph’s scimitar. They hunted by smell, or perhaps the unseen magnetic patterns of the mind’s thoughts. A mere slave boy had no such illustrious heritage, Alim had laughed. Just the unrequited longings of what he would never have.

But Omar knew better. He only had to meet someone once, take note of them, and then he could then feel their presence if they were near enough. It was as if an invisible thread connected him to them, a tingling warmth he could feel in the depth of his being. Alim was the only one he trusted enough to tell of his gift. It really was not a wise thing for slaves to reveal such abilities, less they be judged a threat and culled. Wild blood, the same as the nomads who haunted the dunes. Too many changes by womb mages and the witches of the desert, percolating through undocumented bloodlines. Who knew what changes had been wrought in the past, what gifts were hiding in his flesh? He hadn’t even spoken to Shadisa about this matter.

Ah, Shadisa. Omar still recalled the first time he had noticed Shadisa. She had been a young helper in the kitchens of the great house, her bare elbow balanced on one of the tables as she challenged the other children on the staff to arm-wrestle her. Barely nine himself, he had taken up the challenge and asked Shadisa what she would give him if she lost. ‘A kiss,’ she had brazenly answered. One Omar had sadly never claimed, for her long perfect arms had proved disconcertingly muscular, and he had lost to her in seconds.

He was a lot stronger now, of course, a titan among men as he imagined it. It had been so much easier when they were younger. While it was true that the life of a freeman’s daughter in the town was little better than that of a slave – always subject to the arbitrary whims of her father – when they had been children so much less had been expected from either of them. There had been time enough for Omar and Shadisa to sneak off to the beaches along the south. Empty golden sands, the two of them climbing palm trees and casting dates down into the sand drifting like mist along the surface where the ocean winds stirred it. Building fires from driftwood and making palaces and castles from sand mounds. Their favourite tree was an old betel palm that had embedded itself along the back of the shoreline, its feathered leaves perfect for hiding them as they waited to ambush other children. In its mottled shade they would sway and discuss who were the bigger tyrants among the great house’s staff and the water farm’s workers, quickest with the switch and harshest with the load of duties. Spending time larking about the sands with Shadisa seemed the most natural thing in the world – the one thing he had to look forward to, the one thing he could count on.

That time seemed so distant now, like remembering a lost age of magic. As they had grown older, he had vowed to let nothing separate them. Certainly not the growing differences in their bodies, swelling in increasingly interesting fashions. The way his heart would jump when she held his hand. The way he would find himself looking for excuses to seek her out, or invent chores to bring her out to the water farm. But as they grew older, so did Omar’s awareness of the relative differences in their position. He was a slave; she was the daughter of a freeman. When they had both scurried around under the threat of the switch as children, that difference had seemed academic, simply a word. Nothing in it. But as adulthood beckoned, with each new season their relationship threatened to widen into an unbridgeable canyon. With the passing of every year, they got closer to the point where Shadisa would be expected to meet no man socially save with the company of a chaperone, and a mere slave, never! Omar knew of Shadisa’s father, a very hard man who never smiled, with a reputation for greed and cheating in his dealings. Eyes as cold as ice, and a dry pockmarked face that seemed as seared as the cruelty of the desert. He had once ordered his wife flogged on the flat roof of his house when she miscarried with a son inside her belly. A punishment for whatever she had done to offend the prophets and cause the loss. He had killed a slave too, in a drunken fit, beating the boy’s head in with a piece of firewood one night. Why? Who knew: just because he could, maybe. And what would he do to me if I dared to present myself as a potential suitor, a lowly slave come calling, and without a dowry to boot?

There had been a brief interlude in the inevitable after a disastrous plague had swept the region, carrying away both Omar and Shadisa’s mothers in the same sickening outbreak: a freeman’s wife and female house slave equalized at last by death’s cold touch. So many had died that the old ways and social codes had briefly tottered. There hadn’t been enough hands to do half the work of the town, let alone bother with the strictures of society. The prices of slaves had tripled, along with the wages of freemen; food had become ever more scarce, with insufficient hands to work the fishing boats or keep the irrigation channels clear of sand. Commercial concerns had gone bankrupt all across the province. With one solitary consolation. The grieving over the loss of their mothers had briefly brought Omar and Shadisa even closer. By then, they were of an age where their presence together would be remarked upon, and the beach had become unsafe as a rendezvous; too much danger of being spied upon by a passing townsperson looking to supplement a barren larder by collecting the last tide’s seaweed.

Reluctantly, Omar had abandoned the familiar fan of their palm tree’s leaves, trading it for an ancient ruin in the desert. There was a place ten minutes’ walk from the town, a failed oasis and its collapsed wellspring. There had been a construction there once, as old as time, now with only seven pillars left to make its presence in the world. Shadisa had called them the ‘Pillars of Nuh’ after an old children’s tale, a little bowl of sand offering the shade of its cracked marble columns to rest in. You couldn’t always find it, as the drifting sands sometimes covered it over, before reversing its passage a few weeks later and revealing the dried up watercourse again. When you were inside it, nobody could find you, not unless they stumbled over the top of the basin by accident.

Omar had missed the sound of the sea lapping against the beach and the cry of the gulls, but along with his advancing years, there were other consolations to capture his attention. Like the way Shadisa would flick and curl her golden hair across her soft smooth skin as she gazed up at the clouds, or bump him playfully when he made her laugh with some boast or sly observation. His mimicry of the cooks, gardeners and water engineers working at the great house had been particularly useful in that regard. She would roll about laughing, her teeth flashing as white as the mysterious arched bones they occasionally found jutting out of the dunes, allowing him to pull her close and taste her lips with his. He hadn’t even needed to arm-wrestle Shadisa to claim his prize.

But in all lives there comes a time when the laughter must end, and for him that had been one evening after they’d been staring up at a sunset together, the hot ancient peace of the desert interrupted by a woman’s wails. He and Shadisa had crawled to the top of the dried-out wellspring to see someone fleeing across the sands, a young woman wearing an ivory scooped-neck abaya, her body weighted down with dozens of leather water bottles. Shadisa recognized her first, whispering her name to Omar. One of the staff at the great house, a raven-haired beauty called Gamila. She had been promised in marriage to a water trader, a man of such exceptional ugliness that it was said none of his other three wives could bear him children. Despite his advanced age, or perhaps because of it, Gamila had been promised to the merchant as a cure for his other wives’ infertility – hardly an attractive fate for one so young and vivacious. And here she was, sprinting across the dunes in the cool of the evening, enough water sloshing about her person to follow the caravan road all the way to the next coastal town.

He had hardly needed to hear the distant shouts of a pursuit to know that she wasn’t travelling with her family’s blessing. Shadisa had made to jump up and signal to Gamila to hide with them under the watercourse’s crags, but Omar has pulled her back. If they were discovered out together, Shadisa wouldn’t have needed Gamila’s presence to condemn her in sharing the errant daughter’s fate. Shadisa had struggled and kicked, but the days when she’d been a physical match for Omar were long gone. With his fingers clamped over Shadisa’s mouth, Gamila sprinted past, following the crescent-shaped mound of a sand dune without spotting the dried-up oasis. Then she was gone, the shouts of the chase growing louder, men’s voices hooting and calling to each other, before passing and fading under the darkening sky.

How Shadisa had cursed and damned him for stopping them going to the girl’s aid. He was a fool and a coward and a timid fraud. She couldn’t believe he could be so selfish. Shadisa simply didn’t see how he’d been protecting her all along, saving her from her own thoughtless, reckless actions. Shadisa’s father’s temper would have been volcanic if she had been discovered out in the dunes with a male slave, aiding a girl in dishonouring her family’s name. Gamila had called her own fate down upon her; every slave knew there was only one crime worse than running from your master, and that was getting caught in the attempt. Shadisa didn’t deserve to join the careless house girl in her punishment, and frankly, although he had never voiced it, neither did Omar.

And a wantonly cruel punishment it proved to be. After Gamila had been dragged back to town, the old merchant quickly decided to break off their betrothal in favour of one of Gamila’s younger sisters. Her family then paid for a master womb mage – an expert in the honour-sanctions demanded by wealthy families – to travel to the town from the distant capital. The spurned suitor rejected the lighter punishment of giving Gamila two extra arms and sentencing her to a life of hard labour as a baggage carrier. Instead, the womb mage had buried her in the sand up to her waist on the outskirts of town and inflicted a changeling virus on Gamila, twisting and mutating her form into a cactus-like taproot. What had been her arms and head warped into fleshy green pads, the outline of her face barely visible as lumpy veins of spines. No eyes to see, no mouth to scream; Omar had often prayed there wasn’t enough sentience inside her barrel-like trunk to feel the cuts of travellers’ knives as they sliced wedges out of her body and sucked on the rubbery green flesh for her water. The desert wastes nothing, the travellers would mouth, before discarding the sucked-out flesh in the dust and continuing on their way.

But more than Gamila’s body had changed that day. Ever since then, Shadisa’s attitude towards Omar had cooled. No more walks. No more time together in the old oasis or on the beach. She barely smiled when he approached, and made every excuse to be out of his presence as quickly as possible. Perhaps she was frightened of receiving a similar punishment from her father; perhaps she had seen the price of flouting society’s rules and judged the potential cost of continuing to see Omar too high? Surely she still can’t blame me for what happened to Gamila? It was hardly my fault. You would think that given the time we’ve spent apart, on reflection, she could now see that it is only my quick thinking that saved her. Show me a little gratitude at least. The town’s hunters wouldn’t have just given up looking for Gamila. They would have kept on searching until they found her alongside us, and there wouldn’t now be one body twisted to serve as a taproot outside the town, but three. No, Shadisa’s scared, that has to be it. She’s seen what happens to those who defy their family and she’s fearful. Shadisa just had to be brought to see the greatness burning within her suitor, the infinite potential, then she’d realize that he wouldn’t always be fetching and carrying on a water farm.

‘Hey there,’ ordered Alim, flicking a pebble of limestone rock at Omar, ‘stop mooning over girls too fine for you and open the locks to the next tank. If the fish don’t purge soon, you’ll have a tank of spoiled water and a school of sick salt-fish.’

Omar nodded and made his way to the lock wheels. The last slave who’d killed a batch of salt-fish had been made to eat the sickening black things for a week and almost died of salt poisoning. Yes, the arbitrary punishments, just another perk of being a slave in Cassarabia. Alim helped the young slave in his task, walking down the line of water tanks, twisting the rusting wheels that opened the lock doors, the sloshing water sweeping the fish away to the next stage of the filtering process. The fish were biologicks, of course: the product of womb mage sorcery. Only the House of Barir and the other houses that worshipped the Sect of Ackron, all members of the guild of water farmers, understood exactly how to create and nurture the salt-fish. Adding special vials of hormones to the water supply through their complex life cycle to keep them thrashing and thriving.

Ackron was the fifty-third sect of the Holy Cent, informally known as the trader’s face, and those who embraced the sect often prospered as traders and merchants. That was the theory, at least. The rusting wheels on the water farm’s tanks spoke of a different reality, though. When the plague had spread through the northern provinces of Cassarabia, it had killed over two-thirds of the House of Barir’s people, leaving their coastal water farms undermanned and in the care of the house’s slaves and vagabonds-for-hire like Alim. The bones of the house’s faded glory were laid out in the sand dunes alongside the farm, a handful of metal arches that had been constructed to hold a water pipeline which had never been completed; pipes for fresh drinking water that should have reached all the way to Cassarabia’s capital, bypassing the water traders and the caravans.

It was through the broken arches of the house’s half-finished pipeline that Omar noticed the first visitor rising out of the baking sands, the dark silhouette of a scout atop a saddle raising a long spindly rifle in friendly greeting as the chattering of the sandpedes’ bony legs grew louder in the distance. The insect-like creatures that made up most of the caravan came slithering out of the desert with the dazzling white enamel of thousands of water butts tied to their segmented bodies, flashing towards the water farm.

‘Not good,’ murmured Alim.

‘They are early, old master,’ said Omar, watching the line of water traders coming down the dunes towards them, ‘but so are we. We have enough tanks to fill all their butts. The salt is counted and bagged.’

‘It was I that bagged most of the salt, Omar Ibn Barir,’ spat the old nomad. ‘It is not the traders I talk of. Look …’

Omar shielded his eyes from the sun and turned his gaze to where Alim was pointing. By the silver gates of heaven, the old nomad still had the keen sight from his desert days. There was a keeper on the dune line – one of the respected priests of the hundred sects – riding a camel, breaking away from the main caravan and threading his way through the pump heads that brought sea water up from the harbour. He was bearing straight for the great fortified house overlooking Haffa’s harbour – Master Barir’s residence, as well as that of the beautiful Shadisa, of course. Her olive skin, golden hair and wide green eyes be blessed.

‘It’s just a keeper,’ said Omar. The priests of the Sect of Ackron are always coming and going. The tithes from the House of Barir were important to the sect, and the holy men that received them no doubt said many prayers for the soul of Marid Barir and his profitable water farms.

Alim rubbed the stubble on his old chin. ‘Just a keeper? Have you no eyes to see with, young pup? Look at the green edging around the number fifty-three on his headdress. It is the high keeper of the Sect of Ackron himself.’

An emir of the church, one of the hundred keepers of the Holy Cent of the one true god! What business could he have so far beyond the capital’s comforts? There were no politics here, no court, no temples of note. Just the margins of the desert, a sea breeze, a distant fishing town and the house’s many water farms.

Omar ran a hand through his dark, slightly curly hair. ‘Clearly, my eyes are as perfect as the rest of me. Are you sure it is the high keeper?’

‘Yes,’ sighed the old nomad. ‘I am sure.’

‘He probably wants more money.’

‘Keepers are sent to demand extra tithes from their flock,’ said Alim. ‘Not the high keeper himself. This is bad. In a strong wind, an innocent man’s tiles are blown off a roof the same as the wicked’s.’

‘Is that one of the sayings of the witch that used to travel with your clan?’

‘It is but common sense,’ snapped Alim. ‘Even a town-born slave may drink from that well.’

Omar shrugged and went back to opening the rest of the salt-fish locks, leaving the old nomad to mull over his concerns. Yes, that was the only good thing about being a slave. When you had nothing to lose or hope for, you had little to fear. Worries only came, it seemed, when you had property and status to lose; as a slave, there would be a worker-sized dish of food on his table this evening – because when you owned a beast of burden, it made good sense to feed it and keep it working. And if I am lucky, tomorrow morning might even bring a glimpse of Shadisa’s heart-stopping face. Yes, something will come along for me. Fate will surely accommodate the wittiest and most handsome slave in the empire.

Omar began to hum one of the wild nomad ballads that Alim had taught him.

If he had known what the evening was to bring, he might have changed his tune.

CHAPTER THREE

Jack stumbled to the rail at the front of the stand, his feet constrained by heavy irons and manacles. This was his first time in the middle-court of the Jackelian legal system – his first time in any court for that matter. But even given his lack of experience with such matters, the crowd of illustrators and journalists sitting scribbling away in the public gallery seemed unusually large to his eye. Perhaps if Jack’s father had still been alive, he might have been able to offer some advice – he must have stood in a courtroom like this when the terms of the family’s bankruptcy had been read out. Although perhaps not one so crowded. What was debtors’ prison – the everyday ruin of a common family – compared to the greatest robbery that the capital had nearly seen? And one attempted by the forgotten scrapings of its gutters.

‘The undeserving poor …’ pontificated the judge from his high wooden plinth. A light mist of dust fell from his elaborate wig to be sucked into the pneumatic tubes below where the clerks were sending and receiving reports in between tapping away on the keys of their punch-card writers.

There was a chorus of clanking chains behind Jack as the other members of the gang were pushed to the rail, the public and the newssheet illustrators getting their first look at the felons on trial. The newspapers had no doubt paid a good few pennies to the court officials to ensure that Boyd’s crew would stand there long enough for them to make the drawings that would adorn the late editions of the day’s newssheets.

‘Moral degeneracy …’ the judge growled.

Jack glanced around for their lawyer, who strode forward towards the advocates’ bench. It didn’t look as if things had gone well for the gang in the main hearing. The one Jack hadn’t been allowed to attend while the learned silks argued back and forth, in case the felons’ pauper-like appearance prejudiced the jury. Too many women whose delicate sympathies might have been aroused if they’d been allowed to see the fresh cheeks of the young pickpockets and street thieves who were hauled up in front of the capital’s courts.

‘All results of the failure of the undeserving poor to accept their duties as citizens of the Kingdom, results which are evident all around us,’ sounded the judge. ‘In those so feckless that they have wrongly concluded that the poorhouse rather than paid work should be their employer. And for those too worthless to accept even the generous regime of the workhouse, there are always the pockets of their fellow citizens to pick, the windows of good people’s houses to lever open!’ The judge banged his gavel and pointed it angrily towards the gang. ‘The statutes issued by parliament prevent me sending a message to the slums that would be properly understood. Otherwise, have no doubt that, despite your age, I would have all of you standing on the gallows rather than facing transportation to the colonies.’

Jack breathed a sigh of relief. Thank the stars that the liberal-leaning party of the Levellers was still in government in the House of Guardians.

‘But!’ boomed the judge, his hawk-like nose sniffing in disdain, ‘for the ringleader of this foul crime, I thankfully still have available the option of exercising the middle-court’s full discretion.’

Jack glanced over to where Boyd was standing defiantly, his large frame bearing his chains as though they had been tailored for him. Unlucky for Boyd. Well, at least the publicity concerning the trial would mean there would be a couple of well-wishers in the hanging-day crowd who would bribe the executioner’s attendants to jump up and pull on Boyd’s boots if the rope didn’t break his neck clean after he dropped through the trapdoor. Goodbye Boyd, I would say it’s been nice knowing you, but I’m not that good a liar.

The judge lifted up the small square black cap that those condemned to death were forced to wear while waiting in Bonegate jail. ‘Bring the ringleader forward to receive his cap.’

There was a murmur of sympathy from among those watching on the public seats, a few women tossing their handkerchiefs through the line of constables keeping order. Jack stared at them with contempt. This was real life, not a romantic tragedy put on for the mob’s benefit. Jack’s look of contempt turned to astonishment and then to panic as the guards behind him seized his arms and dragged him out beyond the prisoner’s stall. Pushing him in front of the judge. Me? It’s not me, you idiots!

‘Jack Keats,’ said the judge, glaring down, ‘you have corrupted the benefits of your early training at a guild school to foul ends, leading the ill-educated criminal poor of the Sungate slums on a wicked attempt to undermine, nay, to plunder the hard-earned wealth of those who have chosen to prosper through work rather than squandering their gifts.’

‘I didn’t!’ shouted Jack, pointing back at Boyd still on the prisoner’s stand. ‘I wasn’t the leader. It was him.’

‘Your cowardly lies will not save your neck,’ warned the judge, his eyes narrowing. ‘The members of your gang have all named you as the leader of this wicked enterprise.’

Jack stared back shocked at the ranks of the gang he had followed into the basement vaults of Lords Bank. The young criminals who had been incarcerated together with the threatening bulk of Boyd, while Jack had been locked in solitary confinement inside a security cell designed for those who might be able to work mischief on its transaction-engine lock. Boyd was gazing back coolly at Jack, while Maggie and the others couldn’t even meet his startled eyes.

‘Maggie!’ Jack pleaded. ‘Please, tell them—’

‘Silence!’ thundered the judge. ‘It would be clear to a simpleton which among you had the education, knowledge and skills necessary to break into the vault of Lords Bank. The rest of these gutter-scrapings standing before me do not possess such ingenuity. Dear Circle, man, you’re the only one of them that even has his letters.’

‘It is clear. To a simpleton,’ muttered Jack.

He had been betrayed by all of them, even Maggie. Royally rogered. Jack would have been beaten to death if he hadn’t gone along with Boyd on the robbery, but it seemed now as though he was going to meet his maker anyway. Family, you could only ever trust family. Who were his little two brothers in the poorhouse going to rely on when he was gone? The thought gnawed at Jack’s heart as painfully as his sudden death sentence. People like Boyd, that was who they would fall in with on the streets. Repeating my errors and ending up in a courtroom like this in a few years’ time. Failed them, I’ve failed them.

The guards pushed Jack down to his knees, ready to receive the black cap. The whole courtroom appeared to freeze with the unreality of the occasion. What a dramatic scene this would make for the front of the Middlesteel Illustrated News. A lone figure, bent down to receive the swift mark of Jackelian justice, the judge in his dark robes like a figure from mythology on his high perch. The judge who was about to pass down the black cap to a clerk’s outstretched hand when a court reader stood up to discreetly interrupt him. The clerk was whispering in the judge’s ear and pointing to the corner of the public benches where a man was sitting alone. Jack’s eyes widened. He knew the man sitting on the bench. He had seen those piercing eyes before. The ginger hair. But not the clothes, a large military-style cloak that hid almost all of the man’s body. Where have I seen your face before?

‘It appears,’ announced the judge, ‘that in this case the state has elected to exercise its rights under the articles of impressment.’ Reluctantly storing the black cap back under his perch, the judge looked over the contents of the scroll that had exited the clerk’s transparent vacuum message pipe. ‘However,’ the judge fixed the ginger-haired man on the bench with a steely glare. ‘This impressment order merely suggests the service of the Royal Aerostatical Navy as a suitable sentence, rather than expressly dictating it.’

The ginger-haired man stood bolt upright in anger as if he had been well defied, his cloak a second shadow behind him.

Returning his gaze to Jack, the judge glared down at the young thief. ‘There was a time when the RAN used to be a fit service for gentlemen, and you sir, will never be a gentleman. It pains me to see how in this matter, like so many others, times have changed for the worse. It is therefore the express wish of this court that your life impressment is to be served with a punishment battalion of the New Pattern Army. They may be able to flog some of the criminal tendencies out of your hide before you are required to shed your worthless blood in the service of your nation. Now, officers of the court, kindly remove this lowly piece of gutter-scum from our sight.’

Drawn up from their seats, the mob in the court were in a state of near riot at the unexpected turn of events, and Jack was pulled away to the shouts of frantic questions being hurled down at him by newssheet writers, the repeated banging of the judge’s gavel, the yells of sentences of transportation being passed on the remaining members of the gang. Jack was almost overwhelmed by the stench of the jostling crowd, some laughing at him, some spitting and shouting obscenities, others calling out encouragement and trying to press small gifts of waxpaper-wrapped food into his hands. He got a brief glimpse of the dark cloak of the mysterious figure who had brought news of this bizarrely unexpected intervention in the trajectory of his decline, and then he was on his confused way down the cold damp tunnel and back to the holding pens.

It wasn’t the hangman who would be coming to collect Jack now; it was the army and a death almost as certain, if not quite as immediate.

Jack sat with his back against the cold stone wall of the cell. Before he had seen one, he had always expected a cell to be small, cramped and damp. Well, one out of three isn’t bad. All the damp you could wish for. But the cell was closer to one of the poorhouse’s large chambers where make-work was shipped in – sacks to weave, granite slabs to chip into shape; the whole thing built on an industrial scale to house hundreds of the court’s poor and dispossessed ‘patrons’ while they awaited dispatch to their fate. More permanent cells, transportation to the colonies or for an unlucky few, the hangman’s noose. Jack gazed around at the dirty huddled clumps of humanity. The lucky ones still had family or friends outside with enough coins to pay the authorities for a few comforts for their kin – straw to bed down on and coarse hemp blankets, parcels of food to replace the rancid gruel that was slopped out.

There was a time, a few years ago, when I would have looked down on them, blamed them for their own condition. Now I am them. A time when his father still owned land, collected rents rather than debtors’ bills and gambling losses. The sad truth of the matter was that there wasn’t much that a man wouldn’t do to feed himself. When that person had a family with mouths to feed, there was even less. Jack winced as he tried not to think of his two young brothers sleeping in a place little better than this; different only in name and just as trapped. Poorhouse. Jail. Workhouse. Prison. Interchangeable.

A middle-aged man shuffled over, scratching a long silver beard, wispy and yellowed at the edges from smoking a mumbleweed pipe. ‘You’re the boy who went to guild school?’

‘Brotherhood of Enginemen,’ said Jack. ‘I didn’t sit the exams.’ No, our money had run out long before then.

‘But you’ve got your letters?’ He indicated a couple of families crouched around one of the brick pillars holding up the chamber’s arched roof. They had a newssheet spread open in front of them. Jack nodded. Wearily picking himself up, he walked over to where they were waiting. How his bones creaked and his muscles ached. A day in this rotten hole and already he was moving like he should be drawing a pension. Picking up the paper he looked at the date on the front. ‘It’s two weeks old.’

The man thumped at his chest and hacked out a sawing cough out before croaking. ‘You think the world’s changed much since then?’

‘No.’ Although I had so hoped my world would have. My biggest problem should have been explaining where the sudden shower of gold guineas had appeared from to buy back our estate.

‘Have a look for news of the match workers’ strike,’ said a woman who looked like she might be the mother of one of the families. ‘Are they still bringing in blacklegs to break the strike?’

Jack leafed through the sheaf of large sheets, dark ink staining his fingers, imprinting them from the damp. ‘No mention of the unions here, lady. It’s all talk of a possible war brewing with the Cassarabians.’ They looked up at him, disappointed. There were dozens of families in the cell who had been accused of tearing up cobblestones and throwing them at a factory owner. The recent confrontation between the match workers’ union and the guards who’d been paid to keep the mill open had filled the holding cells.

Jack pointed to the cartoon on the front of the newssheet. A pregnant woman was stretched across a doctor’s table being attended to by a gaggle of surgeons with the faces of famous politicians. A plump young Jackelian boy wearing the uniform of the Royal Aerostatical Navy was jumping up and down in a jealous fit at the sight of a grotesque baby – clearly a Cassarabian – being delivered; the babe also dressed in an opulent airship officer’s uniform. ‘You have a rival, Jack,’ noted the voice balloon hanging over the leering surgeon’s head. ‘Confound you,’ the plump boy was yelling. ‘You promised me nary a sibling.’

‘A bad business,’ said the man.

Jack had to agree. His namesake in the illustration was a Jack Cloudie, an airshipman, and for centuries the monopoly the Kingdom had exercised over the celgas that floated the RAN’s four fleets of airships had kept the nation safe from foreign invasion. Now their belligerent neighbours to the south had secured a supply somehow, and a rival aerial fleet had been spotted patrolling the Jackelian–Cassarabian borders along the uplands. A bad business, indeed. And devilish worse when you’d been sentenced to service in the regiments. First in line when it came to being marched into a fusillade of Cassarabian cannon fire. How much could the world change in two weeks? Always for the worse, that was Jack’s experience. Always for the worse.

The man looked at Jack. ‘What did you get, the boat or the regiments?’

‘The army.’

‘Me too.’ There was a wave of weeping from the woman and her children at that. Of course, it would be transportation to the colonies for them. Without their father. Without her husband. ‘All my life I’ve laboured morning, day and evening. We were just standing on the picket line when management’s men cleared us out with whips and canes. That’s all, just standing there. All my life I’ve done the right thing.’

His voice trailed off.

At least someone here knows what that is.

‘On your feet,’ called the court constable, dragging his cosh along the iron bars of the cell. Jack woke coughing, blinking at the fierce light of the lamp in the policeman’s hand. There were a couple of hulking red-coated soldiers behind the constable, a sergeant and a corporal, the yellow light of the lamp reflected ominously on the death’s heads of their oiled shako hats. The two men fairly strutted along with their left hands balanced on their sheathed sabres to stop them bumping along the damp stone floor. The pair of soldiers might have been Boyd’s older brothers judging by the arrogance of their gait and the unvoiced capacity for violence they left hanging in the air around them.

‘Is this all you have for us?’ said the sergeant, disdainfully.

Jack rubbed the sleep out of his eyes. What were you expecting? A cell full of smartly dressed officers, expert duellists and marksmen for you to press gang into your suicide squad?

‘Not much to look at,’ said the court constable, waving dismissively at the prisoners. ‘But we don’t feed them a fighting man’s rations in here. Give them a plate of gruel and a bayonet and they’ll stick someone for you right enough. Most of them already have.’

‘On your feet, my raggedy boys,’ yelled the sergeant. ‘Move as if you had a purpose – and that was to be chosen by the hand of parliament to serve in its glorious army.’

‘Come on, come on!’ yelled the corporal. ‘Jump to it.’

Jack listened to the creaking of his reluctant bones, a product of the damp, as he joined the others in the cell shuffling through the door that had been opened for them, their leg chains still attached to their ankles. Where were his chains to be removed, Jack wondered? Behind the safe, high stockade of some New Pattern Army barracks, no doubt. Jack felt a sting on the back of his neck as the sergeant encouraged him along with a flick of a swagger stick. ‘Step lively, now. I’ve seen more bleeding life in a fella flogged for sleeping on duty.’

Jack’s wound smarted like a bee sting and he wasn’t the only one to receive some lumps at the hands of the two soldiers sent to collect the convicts. There was an army carriage waiting for them at the other end of the holding cell’s passage, a segmented iron-hulled thing with large spoked wheels. Two soldiers stood in front of it, a man and a female officer, both in brown oiled greatcoats. The appearance of the officer seemed to disconcert the pair of brutes dragging Jack into military service and no wonder. The woman had an angelic face, but frozen with a cold superiority that sat ill at ease with her smooth skin and elegant features; wide eyes that should have radiated softness, glimmered with a piercing intensity instead. She was beautiful the same way an assassin’s dagger was. You might admire it, but only a fool would want to take a closer look.

The male soldier, a broad-shouldered bear of a man with a forked beard salted white with age, came to attention and stamped his boot on the street’s cobbles. ‘The prisoners, lieutenant.’

‘Very good, Oldcastle,’ said the woman.

Both brutes shepherding the convicts into the light halted and saluted back – in what seemed to Jack a rather cursory way – towards the female lieutenant. ‘Prisoners of the Twenty-Second Rifles, sir. The Third Penal Battalion.’

‘Only so long as they don’t escape,’ said the lieutenant.

‘Ah, you’re lucky indeed we caught you two boys in time,’ said the soldier the female officer had named as Oldcastle. He banged the side of the armoured carriage. ‘This old clunker is fine to hold run-of-the-mill ruffians from Bonegate jail, but not this imp!’ His fat fingers jabbed towards Jack. ‘Why, the slippery rascal is the same fellow whose clever fingers nearly teased open the vault of Lords Bank. The locks on the back of your carriage are like bread and butter to a wicked clever thief like this one.’

‘We have sole custody, sir.’

‘House Guards sent us,’ announced the female lieutenant. ‘The general staff want Jack Keats in a secure stockade cell by the end of the day while they consider what to do with him.’

They do?

‘Of course, lads,’ winked Oldcastle. ‘If you want to keep hold of his sly bones, just write us a little note saying that you wouldn’t discharge him across to us. Two strapping fellows like you to look after the pup, he probably won’t escape, will he? The general staff will understand. Look at the thin rascal; why, I reckon the smoke rising from a good hot beef broth might blow the scrawny, thieving mischief-maker right over.’

The corporal pulled open an armoured door on the carriage for the convicts to board, but the sergeant reached out to stop him. ‘If the boy escapes, we’ll both lose our stripes.’ A key was produced, slipped into Jack’s ankle restraints and the corporal pushed him roughly towards the lieutenant. ‘Your prisoner, sir.’

Jack rubbed the life back into his chaffed shins while the corporal looked knowingly at the old soldier. ‘Keep your eyes on him. Some of these street rats got a turn of speed on them like you wouldn’t expect.’

If you think I can run for it, you’ve never spent a night in those cells.

‘Not a problem, corporal.’ Oldcastle unslung a rifle, a cheap-milled brown bess, the army’s weapon of choice. ‘Why, John Oldcastle could shoot a moustache off this lad’s lips at a thousand yards, were he qualified for growing a man’s set of whiskers.’

The corporal nodded in satisfaction at the answer and the two brutes pushed the rest of their shackled prisoners into the armoured wagon.

Jack was marched around the corner to where a shining civilian horseless carriage was waiting, the hum of high-tension clockwork making the air shiver and spooking a horse pulling a coal cart along on the other side of the road. It was the sort of vehicle Jack imagined a general might be chauffeured around in, but the old soldier John Oldcastle pulled himself into the driving pit in the front of the vehicle’s sloped hull while the woman indicated Jack should climb up into the leather passenger seats mounted in the rear. As the lieutenant mounted the steps, her greatcoat fell open, revealing the white facings on her red uniform. Jack’s eyes narrowed in surprise.

‘Do you know what the colour means?’ asked the lieutenant.

‘When you’re in an alehouse,’ said Jack, ‘an army redcoat will drink until he can’t fight. Marines always stay sober enough to dish out some mean lumps.’

John Oldcastle laughed from in front of the carriage. ‘I told you he would be a quick one, Maya. The lad who nearly broke into Lords Bank.’

The woman’s green eyes widened in an appraising stare. ‘Marines stay sober by habit, because they operate under the discipline of a crowded airship, where any jostle that sparks a brawl could lead to fatal damage to a vessel.’ She looked at her sergeant. ‘And Oldcastle, you will address me as First Lieutenant Westwick when others are present.’

‘Yes, sir.’

This odd pair and his situation perplexed Jack. Their uniforms don’t even fit them. First Lieutenant Westwick’s was clearly tailored for a man. This stinks, I can feel it in my bones. ‘Why do you want me …?’

‘Don’t think that I do,’ said the first lieutenant. ‘You wouldn’t be my hundredth choice, let alone my first.’

‘Why does the Royal Aerostatical Navy want me, then?’

The first lieutenant laughed, even as her eyes stayed icy and forbidding. ‘Admiralty House would have gladly let you hang on the gallows, boy. Maybe that’s why we ended up with you. Now, keep your questions to yourself until you’ve learnt how to salute.’

‘I’ll take the lad under my wing,’ Oldcastle called back from the front of the horseless carriage. ‘Keep him on the straight and narrow until he finds his air legs.’

‘Yes, you bloody well will. Could we make this any harder for ourselves?’

‘Beggars can’t be choosers,’ said the soldier, throwing the steering wheel about as he directed the horseless carriage across the capital’s crowded streets.

‘Nothing good will come of this,’ muttered the first lieutenant.

Jack said nothing, although his curiosity was still burning. In truth, he couldn’t agree with the attractive but flinty-looking woman more. Nothing good has happened to me for a long time.

Omar stood on the balcony outside the pavilion that housed his master’s office. He could see over the great house’s fortified walls, look down on the town of Haffa’s white flat-roofed buildings, at the sea glinting like an endless expanse of beaten bronze beyond, and the fishing dhows that stayed close to the coast and still landed generous catches. Other slaves might have stood fretting, wondering if the summons to meet the great Marid Barir might auger a beating for some infraction of the house’s many rules. But what was the point of that when there was a fine view of the harbour to gaze at? Why, he might even be able to watch one of their large paddle steamers come in to dock. The ships needed fresh water for their boilers to drink as much as the Cassarabian people did – using sea water in a ship’s boiler caused rust and eventually explosions when the pressure proved too much.

The guard standing by the master’s door opened it, allowing a tall figure in green-coloured robes to exit; the number fifty-three repeated in ornate script hundreds of times across the shot silk of a priestly dress. It was the high keeper of their house’s sect, and Omar dropped to one knee to give the necessary bow to the great figure. ‘Ben Issman be blessed.’

‘Ben Issman’s blessings upon you too.’ The prince of the church stopped to nod at Omar. Omar snuck a glance upwards. This isn’t usual. Slaves should be invisible to such a great patronage.

‘May I help you, high keeper? I am exceedingly clever and talented for my age and would be happy to put my soul to your service.’

The priest was staring out across the sea that had been Omar’s distraction a second before. ‘I do not think so, my child. I will just stand here a while. There are fish in the sea, and there are men to catch them, all set in place by heaven’s will. How long has the town of Haffa been nestled down there?’

‘For as long as people remember, high keeper.’

‘And perhaps a little longer than that too, eh?’

‘So it may be,’ Omar grinned.

The high keeper patted Omar’s shoulder and walked away as if he was lost in thought. Quite extraordinary. The emir of the church had clearly seen the greatness within Omar where so many others had dismally failed. Omar’s reverie was broken by the cough of the master’s shaven-headed house manager, who was pointing towards the door, left open for him by the guard.

Marid Barir was waiting for Omar behind the wide sparkling surface of his marble-topped desk, the master’s main office silent except for the twisting cooling fan in the ceiling and the cry of the gulls from beyond his massive open window.

Standing up from behind his desk as Omar entered, the short, portly figure brushed his oiled goatee beard while he slowly paced by the window. ‘Good evening to you, Omar Ibn Barir.’

‘Master,’ said Omar. ‘We have filled the traders’ water tanks and loaded all the salt. They will be leaving shortly.’

‘Of course,’ said Marid Barir. ‘But that is not why I have brought you here this night. You have been weighing on my mind, boy.’

‘I am ever your loyal servant, master,’ said Omar bowing and smiling ingratiatingly.

‘You make a very poor one.’

‘I understand everything about water farming, master,’ said Omar, trying to sound hurt.

Marid Barir scowled. ‘At least well enough to keep your desalination line ticking along while you find ever-more inventive ways to skive off. We have tried everything with you. But we never did beat you enough. Would you work harder if I had you flogged every morning?’

‘I would labour mightily even with the weals on my back, master,’ said Omar, trying to keep the smile on his face. ‘With the strength of three normal men.’

‘You are a poor liar,’ said Marid Barir. ‘I think I am done with you, boy.’ He picked up a rubber tube from his desk, opened it and took out a roll of paper to throw at Omar.

‘Master,’ said Omar, glancing at the paper as he unfurled it. ‘What is this?’

‘You were taught to read the panels on your equipment, well enough, boy. What does it look like?’

‘My—’ Omar looked at the elaborate calligraphy on the roll in confusion ‘—my papers of indenture.’

‘You are a freeman from today,’ said Marid Barir. ‘The Ibn is removed from your name. Struck away.’

Omar fought down the rising sensation of confusion, all his certainties, collapsing around him. ‘But why?’

‘There was one week, Omar, when you didn’t wear that perpetual foolish grin of yours. It was a few years ago when you went down to Haffa’s graveyard to try and find the tombstone of your mother.’

‘It was not there,’ said Omar, remembering. But then, mother had just been a slave. How few there were left in the house to remember her after the plague had struck Haffa.

Marid Barir walked to the window and pointed to the hill at the side of the house. ‘You will find her out there.’

‘That is the House of Barir’s family graveyard,’ said Omar.

‘I buried the best of them out there, Omar, after the plague. My wives, my daughters, my sons, my brothers. All of them, but one.’

‘I—’ Omar started.

‘It is not fitting for the last of this house’s blood to die in bondage, Omar Barir. Not even the foolish result of a dalliance with one of my wife’s maids.’

‘But …’ Omar looked at Marid Barir. The great, wealthy Marid Barir, so shrunk by age, by the worries of freemen. My father. Omar was rendered nearly speechless. All these years, he had known he was not fated for the life of a slave. But this? He had never imagined this. ‘Am I to inherit the water farms, the great house, to lead our people?’

‘You misunderstand my intentions, Omar. I have granted you your freedom. I do not intend to shackle you with anything else, least of all running the House of Barir.’

‘You do not intend to …’ The implications of the man’s cold words struck Omar in his heart.

‘My father,’ said Marid Barir, ‘your grandfather, was a renowned caravan master, but he left me nothing. I raised the money to lead my own caravan. I parlayed one trade route into twenty, and then multiplied that into enough to buy a seat on the guild of water farmers, to pay for the first womb mage with the guild spells for our salt-fish. I did this by myself. An ancestor’s wealth is a gilded cage, a curse you cannot escape. Your grandfather was wise enough not to trap his sons in such a cage. This is the gift I pass along to you. It’s a most valuable one.’

‘Then I cannot stay on the desalination lines?’

‘I could not demean the family’s name by having the last son of Barir toiling alongside nomads and slaves.’

‘Then what shall I do?’

‘What is it that you are always saying? Something will come along …’

Omar gawked at his master. No, not my master. My father. Who would have guessed that freedom would feel so uncertain?

‘Congratulations, my son, you have discovered the joys of independence, the consequence of being a freeman. If I had known it would silence your prattling so effectively I might have done it years ago.’

Omar waved his ownership papers at the man, no longer his master. ‘What shall I be?’

‘We are what heaven wills us,’ said Marid Barir.

‘What shall I do? Tell me what I should do now!’ Omar begged.

Marid Barir tapped his greying hair. ‘Think.’ He barked an order and the house manager opened the door. ‘And go.’

Omar looked at the scroll of paper in his hand. It had all the weight of a length of steel pipe from a salt-fish tank.

The house manager shut the door as Omar – Ibn no more – Barir stumbled out.

‘You managed to remove the grin from his mouth, master.’

‘For an hour at least,’ said Marid Barir. ‘Now then, we must make time to prepare.’

The house manager nodded sadly and began to unfurl documents from the satchel he had with him, laying them across the marble table.

Omar blundered down the corridors of the fortified house, all thoughts of the views the pavilions’ windows and gardens afforded an idler forgotten as he struggled to come to terms with his new status. Free. Every certainty of his life broken into pieces. Is this what greatness feels like?

Glancing up he saw Shadisa at the end of the corridor, walking serenely with one of the house cooks, an icebox of fish under her bare arm. Shadisa, the most beautiful of all the women in the house. And he was free. Free to marry her. Surely her scowling-faced father could not object now? Why, if anything, he should thank his stars that the last son of Barir favoured his lowly daughter!

Omar sprinted up to her and held out his ownership papers as if they were a talisman. ‘Shadisa! I am a freeman. I have my papers.’

She looked at Omar as if he had gone mad.

‘Do you not understand? I am not just any freeman. I am the blood of Marid Barir, and he has—’ Omar hesitated, about to say, cast me off. ‘I am my own man.’

Shadisa took the ownership papers Omar was proffering with her spare hand, scanning the contents, and then thrust them back towards Omar as if she was furious at him. ‘You are a fool, Omar. It is you who do not understand.’

‘But …’

‘He has not done this for you,’ said Shadisa, ‘but for himself. It is only to ease his conscience.’

‘I may seek your father out now,’ pleaded Omar. ‘As a freeman.’

Shadisa’s full lips pursed and she forced the papers into Omar’s hand, shaking her head. ‘Go away Omar.’ She turned and fled down the corridor, leaving Omar more confused than ever.

‘Stay away from the house, water farmer,’ warned the cook. ‘Blood of Marid Barir,’ she grunted. ‘After all of this time, to acknowledge you now. Such a fool, such a cruel fool.’

‘Where am I to go?’ Omar nearly yelled out the words.

‘Go back to your wild nomad friend and your stinking salt tanks,’ spat the cook, running after Shadisa.

Omar looked at the crumpled roll of paper in his hand and smashed a fist into the wall, shouting a roar of frustration. Free and poor. Is that why she has rejected me?

He stalked off in search of Alim. In reality, the old nomad had been more of a father towards Omar than Marid Barir ever had. Old Alim would know what was to be done.

For a second, Omar thought that the water traders had changed their minds and returned to the farm. But there were no water-butt laden sandpedes among the group on the rise of the dunes behind the desalination lines, only camels and tall white-robed figures sitting high and proud in their saddles, the bells of the milk goats they kept with them jingling. Alim was walking towards the newcomers, without even the protection of a rifle.

‘Alim! Alim!’ Omar cried. The old water farmer spotted the young man and turned back, orange sand spilling down in front of his boots.

‘Who are these people?’ demanded Omar as Alim drew close.

‘My people,’ said Alim. ‘Tribesmen of the Mutrah.’

‘But you said they would kill you if you walked among them again.’

‘The family of the chief I duelled and killed are all dead now,’ said Alim. ‘Slain in another feud. There are new princes of the sands riding under the moon, men who remember me more kindly. I may return to their fold.’

‘You can’t leave, Alim. I am a freeman. Look. I have my papers.’

‘He finally recognized you?’ Alim sighed.

Omar stared in disbelief at the old nomad. ‘You knew?’

‘Any man too blind to look into Marid Barir’s face and see his eyes in yours could feel your back and know you for what you are from your lack of slave scars.’

‘I can still work with you, Alim. Not here, perhaps, but we can travel to the water farms down south. They are as short-staffed as we are after the plague. They will welcome two expert workers.’

‘I am called,’ said Alim. ‘This is my farm no longer. Wait here, boy. I will speak for you.’ He walked back up the hill and Omar watched the old nomad talking to the tribesmen and pointing back down the dunes towards Omar. The conversation became heated and Alim returned, followed by an old crone with a large hump on her back, bent to the side and filled with water – the result of womb magic. Perhaps her own? Is she a witch of Alim’s people?

‘I have spoken for you,’ said Alim. ‘But you may not come with us.’

‘Why would I want to come, Alim? My place is here in the empire – so is yours.’

The witch was shuffling about, looking at Omar from strange angles and he suspected her stance was not just simply due to the weight of water sloshing about her back. She is seeing into my blood, my very future.

‘Not with us,’ sang the witch. ‘He must not come with us. His path lies down a different line.’ She brushed Omar’s arm gently, then seemed to turn feral, spitting at his feet. ‘Filthy townsman.’

Omar watched the witch hobble back up the slope to the rest of the clan. ‘You would leave the House of Barir to follow that mad old crone?’

‘Foolish boy, do you think it is a coincidence my kin have chosen this day to come for me? She had brought word,’ said Alim. ‘The whisper of the sands, the storm that is following the high keeper here.’

‘What storm?’ demanded Omar.

‘The Sect of Ackron is to be declared heretic,’ said Alim. ‘Not enough tithes have been offered by the sect’s followers to pay the Caliph Eternal the Holy Cent’s one-hundredth annual share. There is a new sect rising, the Sect of Razat. They now have the power in the capital, and they would take their place in the unity of the one true god. They will offer your sect’s tithe money instead. They will be the new fifty-third sect.’

‘That is just politics,’ said Omar.

‘Fool of a freeman,’ said Alim. ‘There can only be a hundred facets of the one true god, not one sect less, not one sect more. When the Sect of Ackron loses its place at the table, its followers will lose all protections under the caliph’s law. Everyone in your father’s house will be declared heretic. The first to arrive here will be brigands and bandits. Everything of value will be looted and plundered. Every man, woman and child healthy enough to be tied to a camel will be taken as slaves.’

‘No,’ protested Omar. ‘I am a freeman now.’

‘Free to die, perhaps,’ said the old nomad. ‘The bandits and slavers and freebooters are not the worst. All the houses willing to renounce the Sect of Ackron have already done so. Only honourable houses like Marid Barir’s have stayed loyal and not shifted their allegiance with the changing wind. The followers of Razat know that anyone who defects at this late stage will harbour hate in their hearts towards them, and they will never allow such vipers to be given sanctuary within the other houses, where they might rise to prosperity again and declare feud in the years to come. The houses that support the new sect will send their troops to Haffa and leave not even the children here alive. Your newly found blood, Omar,’ Alim touched the boy’s arm kindly. ‘It is a poison that has marked you out for certain death.’ He made a strange warbling in the back of his throat and one of the riders came galloping down the dunes, holding the reins of a riderless camel.

Alim smoothly mounted the saddle and threw down a thick leather purse filled with tughra, the paper notes of the empire’s treasury. ‘This is all the money I have saved tending the salt-fish with you over the years. It will be more than enough to pay one of the fishermen to sail you north. Travel away from the empire until you see the sands give way to scrublands, then hills that run green. Those are the uplands of the Jackelians. Tell them you are an escaped slave and you will find sanctuary there in the Kingdom.’

‘But the Jackelians are infidels,’ cried Omar. ‘It is said they deny all gods, even the heathen ones. Their cities run dark with evil smoke and dead, lifeless machines.’

‘They have a council,’ said Alim, ‘which they call parliament. Their ships and soldiers hunt all the empire’s slavers, for which their loathing is well known. They will protect you.’

‘Please, Alim,’ begged Omar. ‘Let me fetch Shadisa and we will travel with you. We will go to another town where no one knows us.’

Alim shook his head sadly. ‘There are family markers in your blood that will be known by any womb mage who chooses to test you, and the assassins that will follow after you will know both your markers and your face well. Whatever happens here, you must never travel across the dunes of the Mutrah, Omar Barir, not unless you are riding with a well-armed caravan. You will not like our punishments for trespassing. If I catch you in the sands after today, I will dig you a pit and bury you up to your waist. Then I will stampede my camels across your head. Filthy townsman.’

‘Please, Alim,’ shouted Omar, taking a couple of hesitant steps forward. ‘In the name of the one true god, Shadisa and I have nothing left here!’

‘There is the desert,’ Alim called back. ‘The desert is always left, and for you the desert is death. Flee, freeman, travel north and fly before the storm.’