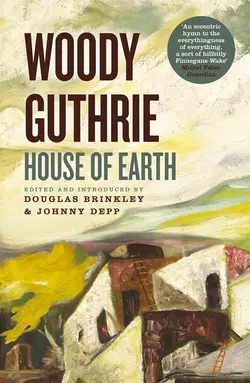

House of Earth

House of Earth

Woody Guthrie

Newly discovered, and with an Introduction by Johnny Depp and Douglas Brinkley, legendary folk singer and American icon Woody Guthrie’s only finished novel: a prophetic and powerful portrait of two hardscrabble farmers struggling to survive the elements and other powerful forces of destruction during the Dust Bowl.Filled with the homespun lyricism and authenticity that have made his songs legendary, this is the story of an ordinary couple’s dream of a better life and their search for love and meaning in a corrupt world. Tike and Ella May Hamlin struggle to plant roots in the arid land of Texas. Living in a precarious wooden shack, they yearn for a sturdy house that will protect them from the treacherous elements. Thanks to a government pamphlet, Tike has the know-how to build a simple adobe dwelling, a structure made from the land itself—fireproof, windproof, a house of earth. The land on which Tike and Ella May live and work on is not theirs, due to larger forces beyond their control—including ranching conglomerates and banks—and their adobe house remains painfully out of reach.A story of rural realism and progressive activism, HOUSE OF EARTH is a searing portrait of hardship and hope set against a ravaged landscape. Combining the moral urgency and narrative drive of John Steinbeck with the erotic frankness of D.H. Lawrence, it is a powerful tale of America from one of our greatest artists.

HOUSE OF EARTH

A NOVEL

WOODY GUTHRIE

Edited and Introduced by

Douglas Brinkley and Johnny Depp

DEDICATION (#)

TO

Nora Guthrie

AND

Tiffany Colannino

AND

Guy Logsdon

EPIGRAPH (#)

I ain’t seen my family in twenty years

That ain’t easy to understand

They may be dead by now

I lost track of them after they lost their land

—BOB DYLAN, “Long and Wasted Years”

And seeing the multitudes, he went up into a mountain: and when he was set, his disciples came unto him:

And he opened his mouth, and taught them, saying,

Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are they that mourn: for they shall be comforted.

Blessed are the meek: for they shall inherit the earth.

—MATTHEW 5:1–5 (King James Version)

CONTENTS

Dedication (#)

Epigraph (#)

Introduction (#)

I DRY ROSIN (#)

II TERMITES (#)

III AUCTION BLOCK (#)

IV HAMMER RING (#)

Acknowledgments (#)

Selected Bibliography (#)

Selected Discography (#)

Biographical Time Line (#)

About the Author (#)

Credits (#)

Copyright (#)

About the Publisher (#)

INTRODUCTION (#)

Life’s pretty tough. . . . You’re lucky ifyou live through it.

—WOODY GUTHRIE

1

On Sunday, April 14, 1935—Palm Sunday—the itinerant sign painter and folksinger Woody Guthrie thought the apocalypse was knockin’ on the door of Pampa, Texas. An immense dust cloud—one that had emanated from the Dakotas—swept grimly across the Panhandle, like the Black Hills on wheels, blotting out sky and sun. As the dust storm approached the town, the bright afternoon was eclipsed by an ominous darkness. Fear engulfed the community. Had its doom arrived? No one in Pampa was safe from this beast. Huddled around a lone lightbulb in a shabby, makeshift wooden house with family and friends, Guthrie, a Christian believer, prayed for survival. The demented winds fingered their way through the loose-fitting windows, cracked walls, and wooden doors of the house. The people in Guthrie’s tight quarters held wet rags over their mouths, desperate to keep the swirling dust from asphyxiating them. Breathing even shallowly and irregularly was an exercise in forbearance. Guthrie, eyes shut tight, face firm, kept coughing and spitting mud.

What Guthrie experienced in Pampa, a vortex in the Dust Bowl, he said, was like “the Red Sea closing in on the Israel children.” According to Guthrie, for three hours that April afternoon a terrified Pampan couldn’t see a “dime in his pocket, the shirt on your back, or the meal on your table, not a dadgum thing.” When the dust storm finally passed, locals shoveled dirt from their front porches and swept basketfuls of debris from inside their houses. Guthrie, incessantly curious, tried to reconcile the joy of being alive with the widespread despair. He surveyed the damage in Pampa the way a veteran reporter would have done. The engines of the usually reliable G.M. motorcars and Fordson tractors had been ruined by thick grime. Huge dunes had accumulated in corrals and alongside wooden ranch homes. Most of the livestock had perished in the storm, the sand clogging their throats and noses. Even vultures hadn’t survived the maelstrom. Images of human anguish were everywhere. Some old people, hit the hardest, had suffered permanent damage to their eyes and lungs. “Dust pneumonia,” as physicians called the many cases of debilitating respiratory illness, became an epidemic in the Texas Panhandle. Guthrie would later write a song about it.

To express his sympathy for the survivors of that Palm Sunday, Guthrie wrote a powerful lament, which set the tone and tenor of his career as a Dust Bowl balladeer:

On the fourteenth day of April,

Of nineteen thirty-five,

There struck the worst of dust storms

That ever filled the sky.

You could see that dust storm coming

It looked so awful black,

And through our little city,

It left a dreadful track.

In the spring of 1935, Pampa was not the only town that had been punished by the agony and losses of the four-year drought. Sudden dust cyclones—black, gray, brown, and red—had also ravaged the high, dry plains of Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Texas, Colorado, and New Mexico. Still, nothing had prepared the region’s farmers, ranchers, day laborers, and boomers for the Palm Sunday when a huge black blob and dozens of other, smaller dust clouds quickly developed into one of the worst ecological disasters in history. Vegetation and wildlife were destroyed far and wide. By summer, the hot winds had sucked up millions of bushels of topsoil, and the continuing drought devastated agriculture in the lowlands. Poor tenant farmers became even poorer because their fields were barren. Throughout the Great Depression, the Great Plains underwent intolerable torment. The prolonged drought of the early 1930s had destroyed crops, eroded land, and caused many deaths. Thousands of tons of dark topsoil, mixed with red clay, had been blown down to Texas from the Dakotas and Nebraska, carried by winds of fifty to seventy miles per hour. A sense of hopelessness prevailed. But the indefatigable Guthrie, a documentarian at heart, decided that writing folk songs would be a heroic way to lift the sagging morale of the people.

Confronted with dreariness and absurdity, with poor folks in distress, many of them financially ruined by the Dust Bowl, Guthrie turned philosophical. There had to be a better way of living than in rickety wooden lean-tos that warped in the summer humidity, were vulnerable to termite infestation, lacked insulation in subzero winter weather, and blew away in a sandstorm or a snow blizzard. Guthrie realized that his neighbors needed three things to survive the Depression: food, water, and shelter. He decided to concern himself with the third in his only fully realized novel: the poignant House of Earth.

A central premise of House of Earth—first conceived in the late 1930s but not fully composed until 1947—is that “wood rots.” At one point in Guthrie’s narrative, there is a tirade against forestry products that rot down … sway … keel over. Someone curses at a wooden home: “Die! Fall! Rot!” Scarred by the dust storm of April 14, Guthrie, a socialist, damned Big Agriculture and capitalism for the degradation of the land. If there is an overall ethos in House of Earth, it’s that those with power—especially Big Banks, Big Lumber, Big Agriculture—should be chastised as repugnant robber barons and rejected by wage earners. Woody was a union man. But his harangues against the powers that be are also tinged with self-doubt. Can one person really fight against wind, dust, and snow? Isn’t venting one’s spleen futile in the end?

Scholars who devote themselves to Woody Guthrie are continually amazed by how much unpublished work the Oklahoma troubadour left behind. He had an unerring instinct for social justice, and he was a veritable writing machine. During his fifty-five years of life, he wrote scores of journals, diaries, and letters. He often illustrated them with good-hearted cartoons, watercolor sketches, and comical stickers. Then there are the memoirs and his more than three thousand song lyrics. He regularly scribbled random ideas on newspapers and paper towels. And he was no slouch when it came to art. But House of Earth—in which wood is a metaphor for capitalist plunderers while adobe represents a socialist utopia where tenant farmers own land—is Guthrie’s only accomplished novel. The book is a call to arms in the same vein as the best ballads in his Dust Bowl catalog.

The setting for House of Earth is the mostly treeless, arid Caprock country of the Texas Panhandle near Pampa. This was Guthrie’s hard-luck country. He was proud that the Great Plains were his ancestral home. It’s perhaps surprising to realize that Guthrie of Oklahoma—who tramped from the redwoods of California to subtropical Florida throughout his storied career—first developed his distinctive writing style in the windswept Texas Panhandle. Guthrie’s treasured Caprock escarpment forms a geological boundary between the High Plains to the east and the Lower Plains of West Texas. The soils in the region were dark brown to reddish-brown sand, sandy loams, and clay loams. They made for wonderful farming. But the lack of shelterbelts—except the Cross Timbers, a narrow band of blackjack and post oak running southward from Oklahoma to Central Texas between meridians 96 and 99—left crops vulnerable to the deadly winds. Soil erosion became a plague, owing to misuse of the land by Big Agriculture, an entity that Guthrie wickedly skewers in the novel.

Guthrie, it seems, knew more about the Caprock country than perhaps any other creative artist who ever lived. He knew the local slang and the idioms of the Panhandle region, the secret hideaways, and the best fishing holes. Throughout House of Earth, Guthrie uses speech patterns (“or something like that”; “shore cain’t”; and “I wish’t I could”) with sure command. Exclamations such as “Whooooo” and “Lookkky!” help establish Guthrie’s populist credibility. He had lived with people very similar to the novel’s hardscrabble characters. His slang expressions are lures similar to those found in O. Henry’s folksy short stories. Building on Will Rogers’s large comedy repertoire, Guthrie, in a little pamphlet titled $30 Wood Help, gave a thumbnail impression of his beloved Lone Star State while carping about the lumber barons turned loan sharks. “Texas,” he wrote, “is where you can see further, see less, walk further, eat less, hitch hike further and travel less, see more cows and less milk, more trees and less shade, more rivers and less water, and have more fun on less money than anywhere else.”

House of Earth has a literary staying power that makes it more than just a curiosity: homespun authenticity, deep-seated purpose, and folk traditions are all apparent in these pages. Guthrie clearly knows the land and the marginalized people of the Lower Plains. In the novel, he draws portraits of four hard-luck characters all recognizable, or partly recognizable, to readers familiar with his songbook: the dutiful tenant farmer “Tike” Hamlin; his feisty pregnant wife, Ella May; a nameless inspector from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) who asks farmers to slaughter their livestock to raise farm prices; and Blanche, a registered nurse. When Tike, full of discord, lashes out at his own ramshackle house—“Die! Fall! Rot!”—he is speaking for all of the world’s poor living in squalor. Like all of Guthrie’s work, which is often erroneously pigeonholed as mere Americana, this book is a direct appeal for world governments to help the hardest-hit victims of natural disasters create new and better lives for themselves. Guthrie contrives to let his readers know in subtle ways that capitalism is the real villain in the Great Depression. It’s reasonable to say that Guthrie's novel could just as easily have been set in a Haitian shantytown or a Sudanese refugee camp as in Texas.

2

It was desperation that first brought Guthrie to forlorn Pampa. He had been born on July 14, 1912, in Okemah, Oklahoma, but in 1927, after Woody’s mother was sent to Central State Hospital for the Insane in Norman (for what today would be diagnosed as Huntington’s disease), his father moved to the Texas Panhandle. Not only were the crops withered in the Oklahoma fields during the 1920s, but the oil fields were also drying up. Tragedy seemed to follow young Woody around like a thundercloud: his older sister, Clara, died in a fire in 1919; then a decade later the Great Depression hit the Great Plains hard, bringing widespread poverty and further dislocation. After spending much of his teens scraping out an existence in Oklahoma, Woody decided in 1929 to join his father in Pampa, a far-flung community in the Texas Panhandle populated largely by cowboys, merchants, itinerant day laborers, and farmers. The mostly self-educated Woody, who had taken to playing the guitar and harmonica for a living, married a Pampa girl, Mary Jennings, who was the younger sister of a friend, the musician Matt Jennings. They would have three children. An oil discovery in the mid-1920s unexpectedly turned Pampa into a boomtown. The Guthries ran a boardinghouse, hoping to capitalize on the prosperity.

Temperamentally unsuited to a sunup-to-sundown job, Guthrie—a slight man weighing only 125 pounds—played a handsome mandolin for tips or sandwiches in every dark juke joint, dance hall, cantina, gin mill, and tequilería from Amarillo to Tucumcari. Leftist and progressive-minded, Guthrie was determined not to let poverty beat him down. He considered himself a straight-talking advocate for truth and love like Will Rogers. With head cocked and chin up, he embodied the authentic West Texas drifter complaining about how rotten life was for the poor. He became a singing spokesman for the impoverished, the debt-ridden, and the socially ostracized. Comic absurdity, however, infused everything Guthrie did. “We played for rodeos, centennials, carnivals, parades, fairs, just bustdown parties,” Guthrie recalled, “and played several nights and days a week just to hear our own boards rattle and our strings roar around in the wind.”

Determined to be a good father to his first daughter, Gwendolyn, Guthrie tried to earn an honest living in Pampa. But he was restless and broke. For extra money, he painted signs for the local C and C Market. When not making music or drawing, he holed up in the Pampa Public Library; the librarian there said he had a voracious appetite for books. Longing to grapple with life’s biggest questions, he joined the Baptist church, studied faith healing and fortune-telling, read Rosicrucian tracts, and dabbled in Eastern philosophy. He opened for business as a psychic in hopes of helping locals with their personal problems. He wanted to be a fulfiller of dreams. His music, grounded in his dedication to improving the lives of the downtrodden, was sometimes broadcast on weekends from a shoe box–size radio station in Pampa. Depending on his mood at any moment, he could be a cornpone comedian or a profound country philosopher of the airwaves. But he was always pure Woody.

His tramps around Texas took him south to the Permian basin, east to the Houston-Galveston area, then up through the Brazos valley into the North Central Plains, and back to the oil fields around Pampa. Always pulling for the underdog, the footloose Guthrie lived in hobo camps, using his meager earnings to buy meals or to shower. He was proud to be part of the downtrodden of the southern zone. His heart swelled with his new social consciousness:

If I was President Roosevelt

I’d make groceries free—

I’d give away new Stetson hats,

And let the whiskey be.

I’d pass out suits of clothing

At least three times a week—

And shoot the first big oil man

That killed the fishing creek.

It was while busking around New Mexico that Guthrie’s gospel of adobe took root. In December 1936, nineteen months after the Black Sunday when the dust storm terrorized the Texas Panhandle, Guthrie had an epiphany. In Santa Fe he visited a Nambé pueblo on the outskirts of town. The mud-daubed adobe walls fascinated him (as they had D. H. Lawrence and Georgia O’Keeffe). The adobe haciendas had hardy wooden rainspouts and bricks of soil and straw that were simple yet perfectly weatherproof, unlike most of the homes of his Texas friends, which were poorly constructed with scrap lumber and cheap nails. These New Mexico adobe homes, with their mud bricks (ten inches wide, fourteen inches long, and four inches high) baked in the sun, Guthrie understood, were built to last the ages.

Adobe was one of the first building materials ever used by man. Guthrie believed that Jesus Christ—his savior—was born in an adobe manger. Such structures seemed to signify Mother Earth herself. If the people in towns like Pampa were going to survive dust storms and snow blizzards, Guthrie decided, they would have to build Nambé-style homes that would stand stoutly until the Second Coming of Christ. In New Mexico, with almost religious zeal, he started painting adobes of “open air, clay, and sky.” In front of the Santa Fe Art Museum one afternoon, an old woman told Guthrie, “The world is made of adobe.” He was transfixed by her comment but managed to nod his head in agreement and reply, “So is man.”

Out of these epiphanies in New Mexico was born the central premise of House of Earth. To Guthrie, New Mexico, the Land of Enchantment, was a crossroads of Hispanic, Native American, African American, Asian, and European cultures. He thought of the state as a mosaic of enduring peoples and cultures. Taos Pueblo—some of its structures as much as five stories high—had been occupied by Native Americans without interruption for a millennium. Santa Fe, founded in 1610, was the first and longest-lasting European capital on US soil. As Guthrie wrote in his song “Bling Blang”—which he recorded for his 1956 album Songs to Grow On for Mother and Child—his day of reckoning, with regard to New Mexico–style adobe, was fast approaching.

I’ll grab some mud and you grab some clay

So when it rains it won’t wash away.

We’ll build a house that’ll be so strong,

The winds will sing my baby a song.

From his inquiries in New Mexico, Guthrie learned that you didn’t have to be a trained mason to build an adobe home. His dream was to live and wander in the Texas Panhandle, and to build a lasting adobe sanctuary on the ranch land he could return to at any time—one that wasn’t a wooden coffin or owned by a bank or vulnerable to the dreaded dust and snow. With the well-reasoned conviction, Guthrie, voice of the rain-starved Dust Bowl, started preaching back in Texas about the utilitarian value of adobe. For five cents, he purchased from the USDA its Bulletin No. 1720, The Use of Adobe or Sun-Dried Brick for Farm Building. Written by T. A. H. Miller, this how-to manual taught poor rural folks (among others) how to build an adobe from the cellar up. In the Panhandle, there was no cheap lumber or stone available, so adobe was the best bet for architecturally sound homes in the Southwest. All an amateur needed was a homemade mixture of clay loam and straw, which helped the brick to dry and shrink as a unit. Constructing a leakproof roof was really the only difficult part. (Emulsified asphalt was eventually used to seal the roofs of adobes.) The rest was as easy as playing tic-tac-toe.

The model US city in the pamphlet was Las Cruces, New Mexico, where 80 percent of all structures were made of adobe. Guthrie promoted this USDA guide for decades. Realizing that dugouts in the Panhandle had endured the Dust Bowl better than wooden aboveground structures, which were vulnerable to wind and termites, Guthrie considered it a public service to promote the notion of adobe dwellings in drought areas. If sharecroppers and tenant farmers in places like Pampa could only own a piece of land—even uncultivable land among arroyos or red rocks—they could build a dream “house of earth” that was fireproof, sweatproof, windproof, snowproof, Dust Bowl–proof, thiefproof, and bugproof.

It was early in January 1937 that Guthrie’s vision of adobe inspired House of Earth. A vicious blizzard, in which dust mixed with snow to turn the white flakes brown, hit the Panhandle, and Guthrie’s miserable twenty-five-dollar-a-month shack rattled in what the Pampa Daily News deemed the most “freakish” storm ever. Never before had residents experienced a summer storm, complete with thunder and lightning, in subzero temperatures. Sitting by the fireplace—the thermostat having frozen—Guthrie dreamed of warm adobes and started plotting House of Earth. In Los Angeles the previous year, Guthrie had befriended the actor and social activist Eddie Albert (who would make his feature film debut in Hollywood’s 1938 version of Brother Rat with Ronald Reagan and would star in the CBS television sitcom Green Acres from 1965 to 1971). Guthrie had been so taken with the charismatic Albert, a proponent of organic farming, that he had given Albert his guitar as a going-away gift. “Well howdy,” Guthrie now wrote to Albert from frigid Pampa. “We didn’t have no trouble finding the dustbowl, and are about as covered up as one family can get. Only trouble is the dust is so froze up it cain’t blow, so it just scrapes around. Had seven or eight fair sized blizzards down here. But was 3 or 4 days a having them. It run us out of our front room the last freeze. We had the cook stove and the heater a going full blast in the house and it was so windy inside it nearly blowed the fires out. We dig in at night and out about sunup. This one has really been a freezeout. Snowed and thawed out 3 times while we was hanging out the clothes. They froze on the line. We took em down just like boards.”

The mercury dropped to six degrees below zero in Pampa, and gas lines froze, leaving homes without heat. While Guthrie was glad to be back home in Pampa—even in wintertime—he was a worried man. What the New York Times called a “blizzard of frozen mud” the color of “cocoa” was pummeling the Great Plains. In Pampa, visibility was often less than two hundred feet. Stuck in his shack, bitterly cold and trying to keep his baby girl from catching a fever, Guthrie fantasized about handcrafting adobe bricks come the spring thaw. Such a bold venture would cost him $300 for supplies for a six-room residence. “You dig you a cellar and mix the mud and straw right in there, sorta with your feet, you know, and you get the mud just the right thickness and you put it in a mould, and you mould out around 20 bricks a day, and in a reasonable length of time you have got enough to build your house,” he wrote to Albert. “You kinda let the weather cure em for around 2 or 3 weeks and the sun bakes em, then you raise up your wall.”

Guthrie’s letter to Eddie Albert—previously unpublished, like House of Earth itself—is a recent discovery. It illuminates how mesmerized Guthrie was by the vision of his own adobe home while trying to survive the brutal winter of 1937.

We sent off to Washington DC and get us back a book about sun dried brick.

Them guys up there around that Dept of Agriculture knows a right smart. They can write about work and make you think you got a job.

They wrote that Adobe Brick book so dadgum interesting that you got to slack up every couple of pages to pull the mud and hay out from between your toes.

People around here for some reason aint got much faith in a adobe mud house. Old Timers dont seem to think it would stand up. But this here Dept of Agr. Book has got a map there in it which shows what parts of the country the dirt will work and tells in no hidden words that sun dried brick is the answer to many a dustblown familys prayer.

Since by a lot of hard work, which us dustbowlers are long on, and a very small cash cost, any family can raise a dern good house which is bug proof, fireproof, and cool in summer, and not windy inside in the winter.

I have been sort of experimenting out here in the yard with mud bricks, and after you make a bunch of em, you’d say yourself if a fellow caint raise up a house out of dust and water, by George, he caint raise it up out of nothing.

Right on hand I got a good cement man when he can get work and also a uncle of mine thats lived up here on the plains for 45 years, and he knows all of these hills and hollers and breaks in the land and canyons, and river bottoms where we can get stuff to built with, like timber and rock and sand, and he’s too old to get a job but just the right age to build.

This cement workers is just right freshly married. But could work some.

Now since this climate is fairly dry and mighty dusty, and in view of the wind that blows, and the wheat that somehow grows, why hadn’t these good cheap houses be introduced around here, which by the bricks in my back yard, I think is a big success.

If folks caint find no work at nothing else they can build em a house. There is plenty of exercise to it.

We’ve owned this little wood house for six years and it has been a blessing over and over, and the same amount of work and money spent on this house will raise one just exactly twice this good from the very well advertised dust of the earth.

It would be nearly dustproof, and a whole lot warmer, and last longer to boot. But folks around here just havent studied it out, or got no information from the government, or somehow are walking around over and overlooking their own salvation.

Local lumber yards dont advertize mud and straw because you cant find a spot on earth without it, but you see old adobe brick houses almost everywhere that are as old as Hitlers tricks, and still standing, like the Jews.

If I was aiming to preach you a sermon on the subject I would get a good lungful of air and say that man is himself a adobe house, some sort of a streamlined old temple.

But what I want to come around to before the paper runs out is this: We’re scratching our heads about where to raise this $300 and we would furnish the labor and work, and we would write up a note of some kind a telling that this house belonged to somebody else till we could pay it out. . . .

Course the payments would have to run pretty low till we could get strung out and the weather thaw out and the sun take a notion to come out, but it would be a loan and as welcome as a gift.

In this case, a few retakes on the lenders part could shore change a mighty bleak picture into a good one, and maybe an endless One.

Starting in the late 1930s, Guthrie toyed with the idea of writing a panegyric to survivors of the Dust Bowl with adobe as the leitmotif. Because John Steinbeck had stolen his thunder by writing The Grapes of Wrath, about the Okie migration westward from Oklahoma and Texas to California, Guthrie decided to focus instead on his own authentic experience as a survivor of Black Sunday and the great mud blizzard. Also, to his ears, the dialect of Steinbeck’s uprooted Joads fell short of realism. To Guthrie, true-to-life bad grammar was the essential way to capture the spirit of how people really talked on the frontier. Like Joel Chandler Harris, the author of the Uncle Remus tales, he was an excellent listener. So House of Earth, in Guthrie’s mind, would be less an adulterated documentation of the meteorological calamities than a pioneering work in capturing Texas-Okie dialects. Steinbeck, like all reporters, focused on the dust cyclones, but Guthrie knew that the frigid winter storms in West Texas during the Dust Bowl era also crippled his fellow plainsmen. Guthrie granted Steinbeck the diploma for documenting the diaspora to California. Nevertheless, he himself claimed for literature those brave and stubborn souls who decided to stay put in the Texas Panhandle. It was one thing for Steinbeck, in The Grapes of Wrath, to feature families who were searching for a land of milk and honey, but Guthrie’s own heart was with those stubborn dirt farmers who remained behind in the Great Plains to stand up to the bankers, lumber barons, and agribusinesses that had desecrated beautiful wild Texas with overgrazing, clear-cutting, strip-mining, and reckless farming practices. The gouged land and the working folks got diddly-squat … nothing … zero … nada … zilch. (For a while Guthrie used the nom de plume Alonzo Zilch.)

While Guthrie’s twenty-five-year-old heart stayed in Texas, his legs would soon be bound for California. Much like Tike Hamlin, the main character in House of Earth, Guthrie paced the floorboards of his hovel at 408 South Russell Street in Pampa during the great mud blizzard of 1937, wondering how to find meaning in the drought-stricken misery of the Depression. His salvation required a choice: to go to California or to build an adobe homestead in Texas. When the character Ella May Hamlin screams, “Why has there got to be always something to knock you down? Why is this country full of things you can’t see, things that beat you down, kick you down, throw you around, and kill out your hope?” the reader feels that Guthrie is expressing his own deep-seated frustration. He decided he would have to try his luck in California if he wanted a steady income. Having learned the Carter Family’s old-style country tunes, and with original songs like “Ramblin’ Round” and “Blowing Down This Old Dusty Road” in his repertoire, he was determined to become a folksinger who mattered. In early 1937—the exact week is unknown, but it was after the snow had thawed—Guthrie packed up his painting supplies, put new strings on his guitar, and bummed a ride in a beer delivery truck to Groom, Texas. Hopping out of the cab and waving good-bye, he started hitching down Highway 66 (what Steinbeck called the “road of flight”), where migrants were begging for food in every flyspeck town, to Los Angeles.

There is an almost biblical sense of trials and tribulations in the obstacles Guthrie would confront in California. Like all the other migrants on Highway 66, he always felt starvation banging on his rib cage. From time to time, he pawned his guitar to buy food. Like the photographer Dorothea Lange, he visited farm camps in California’s San Joaquin Valley, stunned to see so many children suffering from malnutrition. But then Guthrie’s big break came when he landed a job as an entertainer on KFVD radio in Los Angeles, singing “old-time” traditional songs with his partner Maxine Crissman (“Lefty Lou from Mizzou”). His hillbilly demeanor was affecting, and the local airwaves allowed Guthrie to reach fellow workers in migrant camps with his nostalgic songs about life in Oklahoma and Texas. For a while, he broadcast out of the XELO studio from Villa Acuña in the Mexican state of Coahuila; the station’s powerful signal went all over the American Midwest and Canada, unimpeded by topography and unfettered by FCC regulations.

Many radio station owners wanted Guthrie to be a smooth cowboy swing crooner like Bob Wills (“My Adobe Hacienda”) and Gene Autry (“Back in the Saddle Again”). Guthrie, however, had developed a different strategy for folksinging that he clung to uncompromisingly. “I hate a song that makes you think you’re not any good,” he explained. “I hate a song that makes you think that you are just born to lose. Bound to lose. No good to nobody. No good for nothing. Because you are either too old or too young or too fat or too slim or too ugly or too this or too that … songs that run you down or songs that poke fun of you on account of your bad luck or your hard traveling. I am out to fight those kinds of songs to my very last breath of air and my last drop of blood.”

When Guthrie became a “hobo reporter” for The Light in 1938, he traveled extensively, reporting on the 1.25 million displaced Americans of the late 1930s. The squalor of the migrant camps angered him. He kept wishing the poor could live in adobe homes. “People living hungrier than rats and dirtier than dogs,” Guthrie wrote, “in the land of sun and a valley of night.” Guthrie came to understand that, contrary to myth, these so-called Dust Bowl refugees hadn’t been chased out of Texas by dusters; nor had they been made obsolete by large farm tractors. They were victims of banks and landlords who had evicted them simply for reasons of greed. These money-grubbers wanted to evict tenant farmers in order to turn a patchwork quilt of little farms into huge cattle conglomerates, and they thereby forced rural folks into poverty. During his travels around California, Guthrie saw migrants living in cardboard boxes, mildewed tents, filthy huts, and orange-crate shanties. Every flimsy structure known to mankind had been built, but adobe homes were nowhere to be found. This rankled Guthrie boundlessly. What would Jesus Christ think of these predatory money changers destroying the family farms of America and forcing good folks to live in wretched lean-tos? “For every farmer who was dusted out or tractored out,” Guthrie said, “another ten were chased out by bankers.”

The Franklin Roosevelt administration tried to help poor farmers through the federal Resettlement Administration (the successor to the Farm Security Administration, famous for collaborating with such artists as Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Pare Lorentz) by issuing grants of ten to forty-five dollars a month to the down-and-out; farmers would line up at the Resettlement Administration offices for these grants. President Roosevelt also aimed to help farmers like the Hamlins by ordering the US Forest Service to plant millions of acres of trees and shrubs on farms to serve as shelterbelts (and reduce wind erosion) and by having the Department of Agriculture start digging lakes in Oklahoma and Texas to provide irrigation for the dry iron grass. These noble New Deal efforts helped but didn’t completely solve the crisis.

3

The legend of Guthrie as a folksinger is etched in the collective consciousness of America. Compositions like “Deportee,” “Pastures of Plenty,” and “Pretty Boy Floyd” became national treasures, like Benjamin Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanack and Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. With the slogan “This Machine Kills Fascists” emblazoned on his guitar, Guthrie tramped around the country, a self-styled cowboy-hobo and jack-of-all-trades championing the underdog in his proletarian lyrics. When Guthrie heard Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America” sung by Kate Smith ad nauseam in 1939, on radio stations from coast to coast, he decided to strike out against the lyrical rot and false comfort of the patriotic song. Holed up in Hanover House—a low-rent hotel on the corner of Forty-Third Street and Sixth Avenue—Guthrie wrote a rebuttal to “God Bless America” on February 23, 1940. He originally titled the song “God Blessed America” but eventually settled on “This Land Is Your Land.” Because Guthrie saved thousands of his song lyrics in first and final drafts, we’re lucky to still have the fourth and sixth verses of the ballad, pertaining to class inequality:

As I went walking, I saw a sign there,

And on the sign there, it said “no trespassing.” *

But on the other side, it didn’t say nothing,

That side was made for you and me.

In the squares of the city, in the shadow of a steeple;

By the relief office, I’d seen my people.

As they stood there hungry, I stood there asking,

Is this land made for you and me?

Guthrie signed the lyric sheet, “All you can write is what you see, Woody G., N.Y., N.Y., N.Y.” (During that week in Hanover House, the hyperproductive Guthrie also wrote “The Government Road,” “Dirty Overhalls,” “Will Rogers Highway,” and “Hangknot Slipknot.”)

Over the decades, “This Land Is Your Land” has become more a populist manifesto than a popular song. It’s Guthrie’s “The Times They Are a-Changin’,” a call to arms. There is a hymnlike simplicity to Woody’s signature tune. The lyric is clear and focused. Woody’s art always reflected his political leanings, but that was all part of his esprit. He wasn’t, in the end, a persona. What you heard was real as rain. There was no separation between song and singer.

Everything about a Guthrie song accentuated the positive in people struggling against all odds. He would trumpet hope at every turn. He even once referred to himself as a “hoping machine,” in a letter when he was courting a future wife. Guthrie sought to empower those who had nothing, to uplift those who had lost everything in the Great Depression, and to comfort those who found themselves repeatedly at the mercy of Mother Nature. He could not help raging at the swinish injustice of it all, in the two fierce verses in “This Land Is Your Land” that slammed private property and food shortages—verses that were lost during the period of McCarthy’s “red scare.” A relatively unknown, but very important, verse—“Nobody living can ever stop me … Nobody living can ever make me turn back”—challenges the agents of the authoritarian state who prevent free access to the land that was “made for you and me.” Reading all the verses now, one is impressed by Guthrie’s ability to elucidate such simple, brutal truths in such resolute words.

In many ways, House of Earth—originally handwritten in a steno notebook and then typed by Guthrie himself—is a companion piece to “This Land Is Your Land.” It’s another not-so-subtle paean to the plight of Everyman. After all, in a socialist utopia, once a Great Plains family acquired land, it would need to build a sturdy domicile on the property. The novel is therefore pitched somewhere between rural realism and proletarian protest, with a static narrative but a lovely portrait of the Panhandle and the marginalized people who made a life there in the 1930s. It’s Guthrie addressing the elemental question of how a sharecropper couple, field hands, could best live in a Dust Bowl–prone West Texas. Trapped in adverse economic conditions, unable to pay their bills or earn anything more than a subsistence wage, Guthrie’s main characters dream of a better way. Tike Hamlin—like Guthrie himself—wants to build an adobe home for his family. Wherever Guthrie went, no matter the day or time, he talked about someday having his own adobe home. “I am stubborn as the devil, want to built it my own self,” Guthrie wrote to a friend in 1947, “with my own hands and my own labors out of pisse de terra sod, soil, and rock and clay.”

Before writing House of Earth, he had composed his autobiography, Bound for Glory, in the early 1940s. In that work, Guthrie proved to be a genius at capturing the rural Texas-Oklahoma dialect in realistic prose. Somehow he managed to straddle the line between “outsider” folk art and “insider” high art. Bound for Glory— which was made into a motion picture in 1976—is an impressive first try from an amateur inspired by native radicalism. Guthrie’s great accomplishment was that his sui generis singing voice, his trademark, prospered in his prose.

Another book of Guthrie’s, Seeds of Man—about a silver mine around Big Bend National Park in Texas—was largely a memoir, though fictionalized in parts. There is an authenticity about this book that was—and still is—ennobling. He saw his next prose project—House of Earth—as a heartfelt paean to rural poverty. (Just a month after Guthrie had written “This Land Is Your Land,” he played the guitar and regaled his audience with stories about hard times in the Dust Bowl at a now legendary benefit for migrant workers hosted by the John Steinbeck Committee to Aid Agricultural Organization.)

What Guthrie wanted to explore in House of Earth was how places like Pampa could be something more than tumbleweed ghost towns, how sharecropping families could put down permanent roots in West Texas. He wanted to tackle such topics as overgrazing and the ecological threats inherent in fragmenting native habitats. He elucidated the need for class warfare in rural Texas, for a pitchfork rebellion of the 99 percent working folks against the 1 percent financiers. His outlook was socialistic. (Bricks to all landlords! Bankruptcy to all timber dealers! Curses on real estate maggots glutting themselves on the poor!) And he unapologetically announces that being a farmer is God’s highest calling.

One of the main attractions of Guthrie’s writing—and of House of Earth in particular—is our awareness that the author has personally experienced the privations he describes. Yet this is different from pure autobiography. Guthrie gets to the essence of poor folks without looking down on them from a higher perch like James Agee or Jacob Riis. His gritty realism is communal, expressing oneness with the subjects. The Hamlins, it seems, have more in common with the pioneers of the Oregon Trail than with a modern-day couple sleeping on rollout beds in Amarillo during the Internet age. Objects such as cowbells, oil stoves, flickering lamps, and orange-crate shelves speak of a bygone era when electricity hadn’t yet made it to rural America. But while the atmosphere of House of Earth places the novel firmly in the Great Depression, the themes that Guthrie ponders—misery, worry, tears, fun, and lonesomeness—are as old as human history. Guthrie’s aim is to remind readers that they are merely specks of dust in the long march forward from the days of the cavemen.

The Hamlins have a hard life in a flimsy wooden shack, yet exist with extreme (and emotionally fraught) vitality. The reader learns at the outset that their home is not up to the function of keeping out the elements. So Tike starts exasperatedly espousing the idealistic gospel of adobe. On the farm, life persists, and the reader is treated to an extended, earthy lovemaking scene. This intimate description serves a purpose: Guthrie elevates the biological act to a representation of Tike and Ella May’s oneness with the land, the farm, and each other. And yet, the land is not the Hamlins’ to do with as they please—and so the building of their adobe house remains painfully out of reach. The narrative then concerns itself with domestic interactions between Tike and Ella May. Despite their great energy and playfulness, dissatisfaction wells up in them. In the closing scenes, in which Ella May gives birth, we learn more about their financial woes and how tenant farmers lived on tenterhooks during the Great Depression when they had no property rights.

4

When the folklorist Alan Lomax read the first chapter of House of Earth (“Dry Rosin”), he was bowled over, amazed at how Guthrie expressed the emotions of the downtrodden with such realism and dignity. For months Lomax encouraged Guthrie to finish the book, saying that he’d “considered dropping everything I was doing” just to sell the novel. “It was quite simply,” Lomax wrote, “the best material I’d ever seen written about that section of the country.” House of Earth demonstrates that Guthrie’s social conscience is comparable to Steinbeck’s and that Guthrie, like D. H. Lawrence in Lady Chatterley’s Lover, was willing to explore raw sexuality.

Guthrie apparently never showed Lomax the other three chapters of the novel: “Termites,” “Auction Block,” and “Hammer Ring.” His hopes for House of Earth lay in Hollywood. He mailed the finished manuscript to the filmmaker Irving Lerner, who had worked on such socially conscious documentaries as One Third of a Nation (1939), Valley Town (1940), and The Land (1941). Guthrie hoped that Lerner would make the novel into a low-budget feature film. This never came to pass. The book languished in obscurity. Only quite recently, when the University of Tulsa started assembling a Woody Guthrie collection, did House of Earth reemerge into the light. The Lerner estate had found the treasure when organizing its own archives in Los Angeles. The manuscript and a cache of letters written by Guthrie and Lerner to each other were promptly shipped to Tulsa’s McFarlin Library for permanent housing. Coincidentally, while hunting down information about Bob Dylan for a Rolling Stone project, we stumbled on the novel. Like Lomax, we grew determined to have House of Earth published properly by a New York house, as Guthrie surely would have wanted.

The question has been asked: Why wasn’t House of Earth published in the late 1940s? Why would Guthrie work so furiously on a novel and then let it die on the vine? There are a few possible answers. Most probably, he was hoping a movie deal might emerge; that took patience. Perhaps Guthrie sensed that some of the content was passé (the fertility cycle trope, for example, was frowned on by critics) or that the sexually provocative language was ahead of its time (graphic sex of the “stiff penis” variety was not yet acceptable in literature during the 1940s). The lovemaking between Tike and Ella May is a brave bit of emotive writing and an able exploration of the psychological dynamics of intercourse. But it’s a scene that, in the age when Tropic of Cancer was banned, would have been misconstrued as pornographic. Another impediment to publication may have been Guthrie’s employment of hillbilly dialect. This perhaps made it difficult for New York literary circles to embrace House of Earth as high art in the 1940s, though the dialect comes across as noble in our own period of linguistic archaeology. Also, left-leaning originality was hard to mass-market in the Truman era, when Soviet communism was public enemy number one. And critics at the time were bound to dismiss the novel’s enthusiasm for southwestern adobe as fetishistic.

Toward the end of House of Earth, Tike rails against the sheeplike mentality of honest folks in Texas and Oklahoma who let low-down capitalist vultures steal from them. Long before Willie Nelson and Neil Young championed “Farm Aid,” a movement of the 1980s to stop industrial agriculture from running amok on rural families, Guthrie worried about middle-class folks who were being robbed by greedy banks. As Tike prepares to make love to Ella May in the barn scene in House of Earth, his head swirls with thoughts of how everything around him—“house, barn, the iron water tank, the windmill, little henhouse, the old Ryckzyck shack, the whole farm, the whole ranch”—was “a part of him, the same as an egg from the farm went into his mouth and down his throat and was a part of him.” Tike is biologically one with even the hay on his leased property.

In 1947, after years of gestation, House of Earth was finished. Shortly thereafter Guthrie’s health started to deteriorate from complications of Huntington’s disease. While disciples like Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and Pete Seeger popularized his folk repertoire, House of Earth remained among Lerner’s papers. Like a mural by Thomas Hart Benton or a novel by Erskine Caldwell, it was an artifact from a different era: it didn’t fit into any of the standard categories of popular fiction during the Cold War. But, as Guthrie might say, “All good things in due time.” The unerring rightness of southwestern adobe living is now more apparent than ever. Oscar Wilde was right: “Literature always anticipates life.” It’s almost as if Guthrie had written House of Earth prophetically, with global warming in mind.

To read the voice of Guthrie is to hear the many voices of the people, his people, those hardworking Great Plains folks who didn’t have a platform from which their sharp anguish could be heard. His voice was the pure expression of the lost, of the downtrodden, of the forgotten American who scratched out a living from the heartland.

While Guthrie was himself a common man, he was uncommon in his efforts to celebrate the proletariat in his art. He hoped someday Americans could learn how to abolish the laws of debt and repayment. Guthrie wanted to be heard, to count for something. He demanded that his political beliefs be acknowledged, respected, and treated with dignity. As his graphic love scenes demonstrate, he wasn’t scared of anyone. He had no fear. He lived his art. In short, Guthrie inspired not only people of his time, but people of later times enraged by injustice, yearning for truth, searching for that elusive resolution of class inequality.

We consider the publication of House of Earth an integral part of the celebration of the centennial of Woody Guthrie’s birth, a significant cultural event, and a major installment in the corpus of his published work. He wrote the novel as a side project; it was never the focus of his intrepid life of performing his songs from coast to coast. Yet the novel’s intensity guarantees it a place in the ever-growing field of Guthrieana. When we shared Guthrie’s House of Earth with Bob Dylan, he said he was “surprised by the genius” of the engaging prose, a realistic meditation about how poor people search for love and meaning in a corrupt world where the rich have lost their moral compass.

The discovery of House of Earth reinforces Guthrie’s place among the immortal figures of American letters. Guthrie endures as the soul of rural American folk culture in the twentieth century. His music is the soil. His words—lyrics, memoirs, essays, and now fiction—are the adobe bricks. He is of the people, by the people, for the people. Long may his truth be heard by all those who care to listen, all those with hope in their heart and strength in their stride. Guthrie’s proletariat-troubadour legacy is profoundly human, and his work should be forever celebrated. As Steinbeck wrote in tribute, “Woody is just Woody. Thousands of people do not know he has any other name. He is just a voice and a guitar. He sings the songs of a people and I suspect that he is, in a way, that people. Harsh voiced and nasal, his guitar hanging like a tire iron on a rusty rim, there is nothing sweet about Woody, and there is nothing sweet about the songs he sings. But there is something more important for those who still listen. There is the will of a people to endure and fight against oppression. I think we call this the American spirit.”

Douglas Brinkley and Johnny Depp

Albuquerque, New Mexico

I (#)

DRY ROSIN (#)

The wind of the upper flat plains sung a high lonesome song down across the blades of the dry iron grass. Loose things moved in the wind but the dust lay close to the ground.

It was a clear day. A blue sky. A few puffy, white-looking thunderclouds dragged their shadows like dark sheets across the flat Cap Rock country. The Cap Rock is that big high, crooked cliff of limestone, sandrock, marble, and flint that divides the lower west Texas plains from the upper north panhandle plains. The canyons, dry wash rivers, sandy creek beds, ditches, and gullies that joined up with the Cap Rock cliff form the graveyard of past Indian civilizations, flying and testing grounds of herds of leather-winged bats, drying grounds of monster-size bones and teeth, roosting, nesting, and the breeding place of the bald-headed big brown eagle. Dens of rattlesnakes, lizards, scorpions, spiders, jackrabbit, cottontail, ants, horny butterfly, horned toad, and stinging winds and seasons. These things all were born of the Cap Rock cliff and it was alive and moving with all these and with the mummy skeletons of early settlers of all colors. A world close to the sun, closer to the wind, the cloudbursts, floods, gumbo muds, the dry and dusty things that lose their footing in this world, and blow, and roll, jump wire fences, like the tumbleweed, and take their last earthly leap in the north wind out and down, off the upper north plains, and down onto the sandier cotton plains that commence to take shape west of Clarendon.

A world of big stone twelve-room houses, ten-room wood houses, and a world of shack houses. There are more of the saggy, rotting shack houses than of the nicer wood houses, and the shack houses all look to the larger houses and curse out at them, howl, cry, and ask questions about the rot, the filth, the hurt, the misery, the decay of land and of families. All kinds of fights break out between the smaller houses, the shacks, and the larger houses. And this goes for the town where the houses lean around on one another, and for the farms and ranch lands where the wind sports high, wide, and handsome, and the houses lay far apart. All down across this the wind blows. And the people work hard when the wind blows, and they fight even harder when the wind blows, and this is the canyon womb, the stickery bed, the flat pallet on the floor of the earth where the wind its own self was born.

The rocky lands around the Cap Rock cliff are mostly worn slick from suicide things blowing over it. The cliff itself, canyons that run into it, are banks of clay and layers of sand, deposits of gravel and flint rocks, sandstone, volcanic mixtures of dried-out lavas, and in some places the cliff wears a wig of nice iron grass that lures some buffalo, antelope, or beef steer out for a little bit, then slips out from underfoot, and sends more flesh and blood to the flies and the buzzards, more hot meals down the cliff to the white fangs of the coyote, the lobo, the opossum, coon, and skunk.

Old Grandpa Hamlin dug a cellar for his woman to keep her from the weather and the men. He dug it one half of one mile from the rim of Cap Rock cliff. He loved Della as much as he loved his land. He raised five of his boys and girls in the dugout. They built a yellow six-room house a few yards from the cellar. Four more children came in this yellow six-room house, and he took all of his children several trips down along the cliff rim, and pointed to the sky and said to them, “Them same two old eagles flyin’ an’ circlin’ yonder, they was circlin’ there on th’ mornin’ that I commenced to dig my dugout, an’ no matter what hits you, kids, or no matter what happens to you, don’t git hurried, don’t git worried, ’cause the same two eagles will see us all come an’ see us all go.”

And Grandma Della Hamlin told them, “Get a hold of a piece of earth for yerself. Get a hold of it like this. And then fight. Fight to hold on to it like this. Wood rots. Wood decays. This ain’t th’ country to get a hold of nothin’ made out of wood in. This ain’t th’ country of trees. This ain’t even a country fer brush, ner even fer bushes. In this streak of th’ land here you can’t fight much to hold on to what’s wood, ’cause th’ wind an’ th’ sun, an’ th’ weather here’s just too awful hard on wood. You can’t fight your best unless you got your two feet on th’ earth, an’ fightin’ fer what’s made out of th’ earth.” And walking along the road that ran from the Cap Rock back to the home place, she would tell them, “My worst pain’s always been we didn’t raise up a house of earth ’stead of a house of wood. Our old dugout it was earth and it’s outlived a hundred wood houses.”

Still, the children one by one got married and moved apart. Grandma and Grandpa Hamlin could stand on the front porch of their old home place and see seven houses of their sons and daughters. Two had left the plains. One son moved to California to grow walnuts. A daughter moved to Joplin to live with a lead and zinc miner. Rocking back and forth in her chair on the porch, Della would say, “Hurts me, soul an’ body, to look out acrost here an’ see of my kinds a-livin’ in those old wood houses.” And Pa would smoke his pipe and watch the sun go down and say, “Don’t fret so much about ’em, Del, they just take th’ easy way. Cain’t see thirty years ahead of their noses.”

Tike Hamlin’s real name was Arthur Hamlin. Della and Pa had called him Little Tyke on the day that he was born, and he had been Tike Hamlin ever since. The brand of Arthur was frozen into a long icicle and melted into the sun, gone and forgotten, and not even his own papa and mama thought of Arthur except when some kind of legal papers had to be signed or something like that.

Tike was the only one of the whole Hamlin tribe that was not born up on top of the Cap Rock. There was a little oblong two-room shack down in a washout canyon where his mama had planted several sprigs of wild yellow plum bushes near the doorstep. She dug up the plum roots and chewed on them for snuff sticks, and she used the chewed sticks to brush her teeth. The shack fell down so bad that she got afraid of snakes, lizards, flies, bugs, gnats, and howling coyotes, and argued her husband into building a five-room house on six hundred and forty acres of new wheat land just one mile due north, on a straight line, from the old Pa Hamlin dugout.

Tike was a medium man, medium wise and medium ignorant, wise in the lessons taught by fighting the weather and working the land, wise in the tricks of the men, women, animals, and all of the other things of nature, wise to guess a blizzard, a rainstorm, dry spell, the quick change of the hard wind, wise as to how to make friends, and how to fight enemies. Ignorant as to the things of the schools. He was a wiry, hard-hitting, hardworking sort of a man. There was no extra fat around his belly because he burned it up faster than it could grow there. He was five feet and eight inches tall, square built, but slouchy in his actions, hard of muscle, solid of bone and lungs, but with a good wide streak of laziness somewhere in him. He was of the smiling, friendly, easygoing, good-humored brand, but used his same smile to fool if he hated you, and grinned his same little grin even when he got the best or the worst end of a fistfight. As a young boy, Tike had all kinds of fights over all matters and torn off all kinds of clothes and come home with all kinds of cuts and bruises. But now he was in this thirty-third year, and a married man; his wife, Ella May, had taught him not to fight and tear up five dollars’ worth of clothes unless he had a ten-dollar reason.

His hard work came over him by spells and his lazy dreaming came over him to cure his tired muscles. He was a dreaming man with a dreaming land around him, and a man of ideas and of visions as big, as many, as wild, and as orderly as the stars of the big dark night around him. His hands were large, knotty, and big boned, skin like leather, and the signs of his thirty-three years of salty sweat were carved in his wrinkles and veins. His hands were scarred, covered with old gashes, the calluses, cuts, burns, blisters that come from winning and losing and carrying a heavy load.

Ella May was thirty-three years old, the same age as Tike. She was small, solid of wind and limb, solid on her two feet, and a fast worker. She was a woman to move and to move fast and to always be on the move. Her black hair dropped down below her shoulders and her skin was the color of windburn. She woke Tike up out of his dreams two or three times a day and scolded him to keep moving. She seemed to be made out of the same stuff that movement itself is made of. She was energy going somewhere to work. Power going through the world for her purpose. Her two hands hurt and ached and moved with a nervous pain when there was no work to be done.

Tike ran back from the mailbox waving a brown envelope in the wind. “’S come! Come! Looky! Hey! Elly Mayyy!” He skidded his shoe soles on the hard ground as he ran up into the yard. “Lady!”

The ground around the house was worn down smooth, packed hard from footprints, packed still harder from the rains, and packed still harder from the soapy wash water that had been thrown out from tubs and buckets. A soapy coat of whitish wax was on top of the dirt in the yard, and it had soaked down several inches into the earth at some spots. The strong smell of acids and lyes came up to meet Ella May’s nose as she carried two heavy empty twenty-gallon cream cans across the yard.

“Peeewwweee.” She frowned up toward the sun, then across the cream cans at Tike, then back at the house. “Stinking old hole.”

“Look.” Tike put the envelope into her hand. “Won’t be stinky long.”

“Why? What’s going to change it so quick all at once? Hmmm?” She looked down at the letter. “Hmmmm. United States Department of Agriculture. Mmmmm. Come on. We’ve got four more cream cans to carry from the windmill. I’ve been washing them out.”

“Look inside.” He followed her to the mill and rested his chin on her shoulder. “Inside.”

“Grab yourself two cream cans, big boy.”

“Look at th’ letter.”

“I’m not going to stop my work to read no letter from nobody, especially from no old Department of Agriculture. Besides, my hands are all wet. Get those two cans there and help me to put them over on that old bench close to the kitchen window.”

“Kitchen window? We ain’t even got no kitchen.” Tike caught hold of the handles of two of the cans and carried them along at her side. “Kitchen. Bull shit.”

“I make out like it’s my kitchen.” She bent down at the shoulders under the weight of the cans. “Close as we’ll ever get to one, anyhow.” A little sigh of tired sadness was in her voice. Her words died down and the only sound was that of their shoe soles against the hard earth, and over all a cry that is always in these winds. “Whewww.”

“Heavy? Lady?” He smiled along at her side and kept his eye on the letter in her apron pocket.

The wind was stiff enough to lift her dress up above her knees.

“You quit that looking at me, Mister Man.”

“Ha, ha.”

“You can see that I’ve got my hands full of these old cream cans. I can’t help it. I can’t pull it down.”

“Free show. Free show,” Tike sang out to the whole world as the wind showed him the nakedness of her thighs.

“You mean old thing, you.”

“Hey, cows. Horses. Pugs. Piggeeee. Free show. Hey.”

“Mean. Ornery.”

“Hyeeah, Shep. Hyeah, Ring. Chick, chick, chick, chick, chickeeee. Kitty, kitty, kitty, meeeooowww. Meeeooowww. Blow, Mister Wind! I married me a wife, and she don’t even want me to see her legs! Blow!” He dug his right elbow into her left breast.

“Tike.”

“Blowww!”

“Tike! Stop. Silly. Nitwit.”

“Blowwww!” He rattled his two cans as he lifted them up onto the bench. In order to be polite, he reached to take hers and to set them up for her, but she steered out of his reach.

“You’re downright vulgar. You’re filthy-minded. You’re just about the meanest, orneriest, no-accountest one man that I ever could pick out to marry! Looking at me that a way. Teasing me. That’s just what you are. An old mean teaser. Quit that! I’ll set my own cans on the bench.” She lifted her cans.

“Lady.” The devil of hell was in his grin.

“Don’t. Don’t you try to lady me.” Her face changed from a half smile into a deep and tender hurt, a hurt that was older, and a hurt that was bigger than her own self. “This whole house here is just like that old rotten fell-down bench there. That old screen it’s going to just dry up and blow to smithereens one of these days.”

“Let it blow.” Tike held a dry face.

“The wood in this whole window here is so rotten that it won’t hold a nail anymore.” Tears swept somewhere into her eyes as she bit her upper lip and sobbed, “I tried to tack the screen on better to keep those old biting flies out, and they just kept coming on in, because the wood was so rotten that the tacks fell out in less than twenty minutes.”

Tike’s face was sad for a second, but before she turned her eyes toward him, he slapped himself in the face with the back of his hand, in a way that always made him smile, glad or sad. “Let it be rotten, Lady.” He put his hands on his hips and took a step backward, and stood looking the whole house over. “Guess it’s got a right to be rotten if it wants to be rotten, Lady. Goldern whizzers an’ little jackrabbits! Look how many families of kids that little ole shack has suckled up from pups. I’d be all rickety an’ bowlegged, an’ bent over, an’ sagged down, an’ petered out, an’ swayed in my middle, too, if I’d stood in one little spot like this little ole shack has, an’ stood there for fifty-two years. Let it rot. Rot! Rot down! Fall down! Sway in! Keel over! You little ole rotten piss soaked bastard, you! Fall!” His voice changed from one of good fun into words of raging terror. “Die! Fall! Rot!”

“I just hate it.” She stepped backward and stood close up against him. “I work my hands and fingers down to the bones, Tike, but I can’t make it any cleaner. It gets dirtier every day.”

Tike’s hand felt the nipples of her breast as he kissed her on the neck from behind and chewed her gold earrings between his teeth. His fingers rubbed her breasts, then rubbed her stomach as he pulled the letter out of her apron pocket. “Read th’ little letter?”

“Hmh? Just look at those poor old rotted-out boards. You can actually see them rot and fall day after day.” She leaned back against his belt buckle.

He put his arms around her and squeezed her breasts soft and easy in his hands. He held his chin on her right shoulder and smelled the skin of her neck and her hair as they both stood there and looked.

“Department of Agriculture.” She read on the outside.

“Uh-hmm.”

“Why. A little book. Let’s see. Farmer’s Bulletin Number Seventeen Hundred. And Twenty. Mm-hmm.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“The Use of Adobe or Sun Dried Brick for Farm Building.” A smile shone through her tears.

“Yes, Lady.” He felt her breasts warmer under his hands.

“A picture of a house built out of adobe. All covered over with nice colored stucco. Pretty. Well, here’s all kinds of drawings, charts, diagrams, showing just about everything in the world about it.”

“How to build it from th’ cellar up. Free material. Just take a lot of labor an’ backbendin’,” he said. Then a smile was in his soul. “Cost me a whole big nickel, that book did.”

“Adobe. Or Sun-Dried Brick. For Farm Building.” She flipped into the pages and spoke a few slow words. “It is fireproof. It is sweatproof. It does not take skilled labor. It is windproof. It can’t be eaten up by termites.”

“Wahooo!”

“It is warm in cold weather. It is cool in hot weather. It is easy to keep fresh and clean. Several of the oldest houses in the country are built out of earth.” She looked at the picture of the nice little house and flowers on the front of the book. “All very well. Very, very well. But.”

“But?” he said in a tough way. “But?”

“But. Just one or two buts.” She pooched her lips as her eyes dropped down along the ground. “You see that stuff there, that soil there under your feet?”

“Sure.” Tike looked down. “I see it. ’Bout it?”

“That is the but.”

“The but? Which but? Ain’t no buts to what that book there says. That’s a U.S. Gover’ment book, an’ it’s got th’ seal right there, there in that lower left-hand corner! What’s wrong with this soil here under my foot? It’s as hard as ’dobey already!”

“But. But. But. It just don’t happen to be your land.” She tried hard and took a good bit of time to get her words out. Her voice sounded dry and raspy, nervous. “See, mister?”

Tike’s hand rubbed his eye, then his forehead, then his hair, then the back of his neck, and his fingers pulled at the tip of his ear as he said, “’At’s th’ holdup.”

“A house”—her voice rose—“of earth.”

Tike only listened. His throat was so tight that no words could get out.

“A house of earth. And not an inch of earth to build it on.” There was a quiver, a tremble, and a shake in her body as she scraped her shoe sole against the ground. “Oooo, yes,” she said in a way that made fun of them both, of the whole farm, mocked the old cowshed, shamed the iron water tank, made fun of all the houses that lay within her sight. “Yesssss. We could build us up a mighty nice house of earth, if we could only get our hands on a piece of land. But. Well. That’s where the mule throwed Tony.”

“That’s where th’ mule”—he looked toward the sky, then down at the toe of his shoe—“throwed Tony.”

She turned herself into a preacher, pacing up and down, back and forth, in front of Tike. She held her hands against her breasts, then waved them about, beat her fists in the wind, and spoke in a loud scream. “Why has there got to be always something to knock you down? Why is this country full of things that you can’t see, things that beat you down, kick you down, throw you around, and kill out your hope? Why is it that just as fast as I hope for some little something or other, that some kind of crazy thievery always, always, always cuts me down? I’ll not be treated any such way as this any longer, not one inch longer. Not one ounce longer, not one second longer. I never did in my whole life ask for one whit more than I needed. I never did ask to own, nor to rule, nor to control the lands nor the lives of other people. I never did crave anything except a decent chance to work, and a decent place to live, and a decent, honest life. Why can’t we, Tike? Tell me. Why? Why can’t we own enough land to keep us busy on? Why can’t we own enough land to exist on, to work on, and to live on like human beings? Why can’t we?”

Tike sat down in the sun and crossed his feet under him. He dug into the soapy dishwater dirt and said, “I don’t know, Lady. People are just dog-eat-dog. They lie on one another, cheat one another, run and sneak and hide and count and cheat, and cheat, and then cheat some more. I always did wonder. I don’t know. It’s just dog-eat-dog. That’s all I know.”

She sat down in front of him and put her face down into his lap. And he felt the wet tears again on her cheeks. And she sniffed and asked him, “Why has it just got to be dog-eat-dog? Why can’t we live so as to let other people live? Why can’t we work so as to let other folks work? Dog-eat-dog! Dog-eat-dog! I’m sick and I’m tired, and I’m sick at my belly, and sick in my soul with this dog-eat-dog!”

“No sicker’n me, Lady. But don’t jump on me. I didn’t start it. I cain’t put no stop to it. Not just me by myself.” He held the back of her head in his hands.

“Oh. I know. I don’t really mean that.” She breathed her warm breath against his overalls as she sat facing him.

“Mean what?”

“Mean that you caused everybody to be so thieving and so low-down in their ways. I don’t think that you caused it by yourself. I don’t think that I caused it by myself, either. But I just think that both of us are really to blame for it.”

“Us? Me? You?”

“Yes.” She shook her head as he played with her hair. “I do. I really do.”

“Hmmm.”

“We’re to blame because we let them steal,” she told him.

“Let them? We caused ’em to steal?”

“Yes. We caused them to steal. Penny at a time. Nickel at a time. Dime. A quarter. A dollar. We were easygoing. We were good-natured. We didn’t want money just for the sake of having money. We didn’t want other folks’ money if it meant that they had to do without. We smiled across their counters a penny at a time. We smiled in through their cages a nickel at a time. We handed a quarter out our front door. We handed them money along the street. We signed our names on their old papers. We didn’t want money, so we didn’t steal money, and we spoiled them, we petted them, and we humored them. We let them steal from us. We knew that they were hooking us. We knew it. We knew when they cheated us out of every single little red cent. We knew. We knew when they jacked up their prices. We knew when they cut down on the price of our work. We knew that. We knew they were stealing. We taught them to steal. We let them. We let them think that they could cheat us because we are just plain old common everyday people. They got the habit.”

“They really got the habit,” Tike said.

“Like dope. Like whiskey. Like tobacco. Like snuff. Like morphine or opium or old smoke of some kind. They got the regular habit of taking us for damned old silly fools,” she said.

“You said a cuss word, Elly.”

“I’ll say worse than that before this thing is over with!”

“Naaa. Naaa. No more of that there cussin’ outta you, now. I ain’t goin’ to set here an’ listen to a woman of mine carry on in no such a way when she never did a cuss word in her whole life before.”

“You’ll hear plenty.”

“I don’t know why, Lady, never would know why, I don’t s’pose. But them there cuss words just don’t fit so good into your mouth. Me, it’s all right for me to cuss. My old mouth has a little bit of ever’thing in it, anyhow. But no siree, not you. You’re not goin’ to lose your head an’ start out to fightin’ folks by cuss words. I’ll not let you. I’ll slap your jaws.”

Ella May only shook her curls in his lap.

“You always could fight better by sayin’ nice words, anyhow, Lady. I don’t know how to tell you, but when I lose my nut an’ go to cussin’ out an’ blowin’ my top, seems like my words just get all out somewhere in th’ wind, an’ then they get lost, somehow. But you always did talk with more sense, somehow. Seems like that when you say somethin’, somehow or another, it always makes sense, an’ it always stays said. Cuts ’em deeper th’n my old loose flyin’ cuss words.”

“Cuts who?” She lifted her head and shook her hair back out of her face, and bit her lip as she tried to smile. “Who?”

“I don’t know. All of them cheaters an’ stealers you’re talkin’ about.”

“I’m not talking about just any one certain man or woman, Tike. I’m just talking about greed. Just plain old greed.”

“Yeah. I know. Them greedy ones,” he said.

And she said, “No. No. You know, Tike—ah, it may sound funny. But I think that the people that are greedy, well, they believe that it’s right to be greedy. They’ve got a hope, a dream, a vision, inside of them just like I’ve, ah, we’ve got in us. And in a way it’s pitiful, but it’s not really their fault.”

“Hmm?”

“No more than, say, a bad disease was to break out, like some kind of a fever, or some kind of a plague, and all of us would take it, all of us would get it. Some would have it very light, some would have it sort of, well, sort of medium. Others would have it harder and worse, and some would naturally have it bad. Some of us would lose our heads, and some would lose our hands, and some would lose our senses with the fever.”

“Yeah. But who would be to blame for a plague? Cain’t nobody start no fever nor a thing like a plague. Could they, Lady?”

“Filth causes diseases to eat people up.”

“Yeah.”

“And ignorance is the cause of people’s filth.”

“Yeah—but—”

“Don’t but me. And ignorance is caused by your greed.”

“My greed? You mean, ah, me? My greed? You mean that me, my greed caused this farm to be filthy? I didn’t make it filthy. If it was mine, I’d clean th’ damn thing up slicker’n a new hat.”

She sat for a bit and looked out past his shoulder. “I feel the same way. I don’t know. But you can’t put your heart into anything if it’s not your own.”

“Shore cain’t.”

“I don’t know. I never did know. But it looks like to me that we could get together and pass some laws that would give everybody, everybody enough of a piece of land to raise up a house on.”

“Everybody would just go right straight and sell it to get some money to gamble with or to get drunk on, or to fuck with,” he told her. “Gamble. Drink. Fuck.”

“Should be fixed, though, to where if you went and sold your piece of land, then it went back into the hands of the Government, and not some old mean miserly money counter,” she said.

“If th’ Gover’ment was to pass out pieces of land right today, the banks would have it all back in two months.” He laughed.

“And if that happened”—she tilted her head—“then the Government should take it away from the banks and pass it out all over again. What do we pay them for? Fishing.”

“Fuckin’.” Tike laughed again.

She half shut her eyes to get a good close look at his face and said, “Your mind is certainly on sex today.”

“Ever’day.”

“Every single sensible thing that I’ve said here about your house of earth and your land to build it on, you’ve brought sex into it.”

“What do you think I want a house an’ a piece of land for, to concentrate in?”

“Don’t your mind ever think about anything else except just getting a piece of lay?”

“Not that I recollect.”

“How long has your mind been running thisaway?”

“’Fore I learnt how to walk.”

“Silly.”

“Me silly? How come?”

“Oh.” She looked at him. “I don’t know. I guess you were just born sort of silly. How come you to be born so silly, anyhow? Tikey?”

“How come you to be born so perty? Lady?” Inside his overalls Tike felt the movement of his penis as it grew long and hard. In the way he was sitting there was not room enough for his penis to become stiff. His clothing caused it to bend in the middle in a way that dealt him a throbbing pain. He stood up on the ground and spread his legs apart. He reached inside his overalls with his fingers and put it in an upright position and sighed a breath of comfort. His blood ran warmer and the whole world seemed to be flying from under his feet. His old feeling was coming over him, and his eyes looked around the yard for something to say to Ella May.

She stood up and looked down at the ground where she had been sitting. She picked up the Department of Agriculture book. Her eyes watched Tike as he held his hand inside his overalls. She saw his lips tremble and heard him inhale a deep lungful of air. “What have you caught in there, Tikey, a frog?”

“Snake,” Tike said. “Serpent.”

“You seem to be having quite a scuffle.”

“Fight ’im day an’ night.”

“And he seems to be getting just a little the best of it from what I can see.” She watched him from the corner of her eye.

He was a moment making his reply. He took a step forward and caught hold of her hand. She could measure the heat of his desire by the moisture in the palm of his hand. He tugged at her slow and easy and stepped backward in the path of the cow barn. “Psssst. Lady. Psst. Lady. Wanta see somethin’? Huh?”

“What are you trying to do to me? Mister?” She pulled back until she had spoken, then she gave in and walked along. “Will you please state?”

“Shh. Gonna show you somethin’.”

“Something? Something what?”

“Shh. Just somethin’.” It was funny to her to see him try to creep along without making any noise, when his heavy work shoes made such a grinding and a crushing sound under the soles that he could be heard all over the ranch. “Shh. C’mon.”