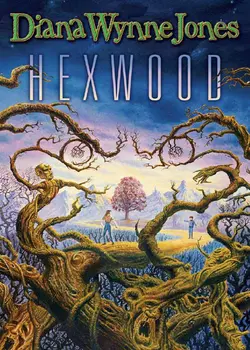

Hexwood

Diana Wynne Jones

“All I did was ask you for a role-playing game. You never warned me I’d be pitched into it for real! And I asked you for hobbits on a Grail quest, and not one hobbit have I seen!”Hexwood Farm is a bit like human memory; it doesn’t reveal its secrets in chronological order. Consequently, whenever Ann enters Hexwood, she cannot guarantee on always ending up in the same place or even the same time.Hexwood Farm is full of machines that should not be tampered with – and when one is, the aftershock is felt throughout the universe. Only Hume, Ann and Mordion can prevent an apocalypse in their struggle with the deadly Reigners – or are they too being altered by the whims of Hexwood?A complex blend of science fiction and all sorts of fantasy – including fantasy football!!

Diana Wynne Jones

HEXWOOD

ILLUSTRATED BY TIM STEVENS

Copyright (#uad1afb1d-a984-5aa1-a6a7-e5ccb7f0016c)

First published by Methuen Children’s Books Ltd 1993

First published in paperback by Collins 2000

Published by HarperCollins Children’s Books

1 London Bridge Street,

London, SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Text copyright © Diana Wynne Jones 1993

Illustration by Tim Stevens 2000

The author and illustrator assert the moral right to be identified as the author and illustrator of the work.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780006755265

Ebook Edition © NOVEMBER 2012 ISBN: 9780007440184

Version: 2018-06-21

Dedication (#uad1afb1d-a984-5aa1-a6a7-e5ccb7f0016c)

For Neil Gaiman

Contents

Cover (#u661908c4-19a7-53a5-a994-c611aa5197ca)

Title Page (#ufa95c30f-87e6-5b4b-b37c-9e9d4e187939)

Copyright

Dedication

PART ONE

1

2

3

4

5

PART TWO

1

2

3

4

5

PART THREE

1

2

3

4

5

PART FOUR

1

2

3

4

5

PART FIVE

1

2

3

4

5

PART SIX

1

2

3

4

5

PART SEVEN

1

2

3

4

5

PART EIGHT

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

PART NINE

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Other Works

About the Publisher

(#uad1afb1d-a984-5aa1-a6a7-e5ccb7f0016c)

(#uad1afb1d-a984-5aa1-a6a7-e5ccb7f0016c)

The letter was in Earth script, unhandily scrawled in blobby blue ballpoint. It said:

Hexwood Farm

Wednesday 3 March 1993

Dear Sector Controller,

We though we better send to you in Regional straight off. We got a right problem here. This fool clerk, calls hisself Harrison Scudmore, he went and started one of these old machines running, the one with all the Reigner seals on it, says he overrode the computers to do it. When we say a few words about that, he turns round and says he was bored, he only wanted to make the best all-time football team, you know King Arthur in goal, Julius Ceasar for striker, Napoleon midfield, only this team is for real, he found out this machine can do that, which it do. Trouble is we don’t have the tools nor the training to get the thing turned off, nor we can’t see where the power’s coming from, the thing’s got afield like you wouldn’t believe and it won’t let us out of the place. Much obliged if you could send a trained operative at your earliest convenience.

Yours truly

W. Madden

Foreman Rayner Hexwood Maintenance

(European Division)

PS He says he’s had it running more than a month now.

Sector Controller Borasus stared at the letter and wondered if it was a hoax. W. Madden had not known enough about the Reigner Organisation to send his letter through the proper channels. Only the fact that he had marked his little brown envelope URGENT!!! had caused it to arrive in the Head Office of Albion Sector at all. It was stamped all over with queries from branch offices and had been at least two weeks on the way.

Controller Borasus shuddered slightly. A machine with Reigner seals! If this was not a hoax, it was liable to be very bad news. “It must be someone’s idea of a joke,” he said to his Secretary. “Don’t they have something called April Fools’ Day on Earth?”

“It’s not April there yet,” his Secretary pointed out dubiously. “If you recollect, sir, the date on which you are due to attend their American conference – tomorrow, sir – is 20 March.”

“Then maybe the joker mistimed his letter,” Controller Borasus said hopefully. As a devout man who believed in the Divine Balance perpetually adjusted by the Reigners, and himself as the Reigners’ vicar on Albion, he had a strong feeling that nothing could possibly go really wrong. “What is this Hexwood Farm thing of theirs?”

His Secretary as usual had all the facts. “A library and reference complex,” he answered, “concealed beneath a housing estate not far from London. I have it marked on my screen as one of our older installations. It’s been there a good twelve hundred years, and there’s never been any kind of trouble there before, sir.”

Controller Borasus sighed with relief. Libraries were not places of danger. It had to be a hoax. “Put me through to the place at once.”

His Secretary looked up the codes and punched in the symbols. The Controller’s screen lit with a spatter of expanding lights. It was not unlike what you see when you press your fingers into your eyes.

“Whatever’s that?” said the Controller.

“I don’t know, sir. I’ll try again.” The Secretary cancelled the call and punched the code once more. And again after that. Each time the screen filled with a new flux of expanding shapes. On the Secretary’s third attempt, the coloured rings began spreading off the viewscreen and rippling gently outwards across the panelled wall of the office.

Controller Borasus leant across and broke the connection, fast. The ripples spread a little more, then faded. The Controller did not like the look of it at all. With a cold, growing certainty that everything was not all right after all, he waited until the screen and the wall at last seemed back to normal and commanded, “Get me Earth Head Office.” He could hear that his voice was half an octave higher than usual. He coughed and added, “Runcorn, or whatever the place is called. Tell them I want an explanation at once.”

To his relief, things seemed quite normal this time. Runcorn came up on the screen, looking entirely as it should, in the person of a Junior Executive with beautifully groomed hair and a smart suit, who seemed very startled to see the narrow, august face of the Sector Controller staring out of the screen at him, and even more startled when the Controller asked to speak to the Area Director instantly. “Certainly, Controller. I believe Sir John has just arrived. I’ll put you through—”

“Before you do,” Controller Borasus interrupted, “tell me what you know about Hexwood Farm.”

“Hexwood Farm!” The Junior Executive looked nonplussed. “Er – you mean – Is this one of our information retrieval centres you have in mind, Controller? I think one of them is called something like that.”

“And do you know a maintenance foreman called W. Madden?” demanded the Controller.

“Not personally, Controller,” said the Junior Executive. It was clear that if anyone else had asked him this question, the Junior Executive would have been very disdainful indeed. He said cautiously, “A fine body of men, Maintenance. They do an excellent job servicing all our offworld machinery and supplies, but of course, naturally, Controller, I get into work some hours after they’ve—”

“Put me through to Sir John,” sighed the Controller.

Sir John Bedford was as surprised as his Junior Executive. But after Controller Borasus had asked only a few questions, a slow horror began to creep across Sir John’s healthy businessman’s face.

“Hexwood Farm is not considered very important,” he said uneasily. “It’s all history and archives there. Of course that does mean that it holds a number of classified records – it has all the early stuff about why the Reigner Organisation keeps itself secret here on Earth – how the population of Earth arrived here as deported convicts and exiled malcontents, and so forth – and I believe there is a certain amount of obsolete machinery stored there too – but I can’t see how our clerk would be able to tamper with any of that. We run it through just the one clerk, you see, and he’s pretty poor stuff, only in the Grade K information bracket—”

“And Grade K means?” asked Controller Borasus.

“It means he’ll have been told that Rayner Hexwood International is actually an intergalactic firm,” Sir John explained, “but that should be absolutely all he knows – probably less than Maintenance, who are also Grade K. Maintenance pick up a thing or two in the course of their work. That’s unavoidable. They visit every secret installation once a month to make sure everything stays in working order, and to supply the stass-stores with food and so forth, and I suspect quite a few of them know far more than they’ve been told, but they’ve been carefully tested for loyalty. None of them would play a joke like this.”

Sir John, Controller Borasus decided, was trying to talk himself out of trouble. Just what you would expect from a backward hole like Earth. “So what do you think is the explanation?”

“I wish I knew,” said the Director of Earth. “Oddly enough, I have two complaints on my desk just this morning. One is from an Executive in Rayner Hexwood Japan, saying that Hexwood Farm is not replying to any of his repeated requests for data. The other is from our Brussels branch, wanting to know why Maintenance has not yet been to service their power plant.” He stared at the Controller, who stared back. Each seemed to be waiting for the other to explain. “That foreman should have reported to me,” Sir John said at length, rather accusingly.

Controller Borasus sighed. “What is this sealed machine that seems to have been stored in your retrieval centre?”

It took Sir John Bedford five minutes to find out. What a slack world! Controller Borasus waited, drumming his fingers on the edge of his console, and his Secretary sat not daring to get on with any other business.

At last Sir John came back on the screen. “Sorry to be so long. Anything with Reigner seals here is under heavy security coding, and there turn out to be about forty old machines stored in that library. We have this one listed simply as One Bannus, Controller. That’s all, but it must be the one. All the other things under Reigner seals are stass-tombs. I imagine there’ll be more about this Bannus in your own Albion archives, Controller. You have a higher clearance than—”

“Thank you,” snapped Controller Borasus. He cut the connection and told his Secretary, “Find out, Giraldus.”

His Secretary was already trying. His fingers flew. His voice murmured codes and directives in a continuous stream. Symbols scrolled, and vanished, and flickered, jumping from screen to screen, where they clotted with other symbols and jumped back to enter the main screen from four directions at once. After a mere minute, Giraldus said, “It’s classified maximum security here too, sir. The code for your Key comes up on your screen – now.”

“Thank the Balance for some efficiency!” murmured the Controller. He took up the Key that hung round his neck from his chain of office and plugged it into the little-used slot at the side of his console. The code signal vanished from his screen and words took its place. The Secretary of course did not look, but he saw that there were only a couple of lines on the screen. He saw that the Controller was reacting with considerable dismay. “Not very informative,” Borasus murmured. He leant forward and checked the line of symbols which came up after the words in the smaller screen of his manual. “Hm. Giraldus,” he said to his Secretary.

“Sir?”

“One of these is a need-to-know. Since I’m going to be away tomorrow, I’d better tell you what this says. This W. Madden seems to have his facts right. A Bannus is some sort of archaic decision-maker. It makes use of a field of theta-space to give you live-action scenarios of any set of facts and people you care to feed into it. Acts little plays for you, until you find the right one and tell it to stop.”

Giraldus laughed. “You mean the clerk and the maintenance team have been playing football all this month?”

“It’s no laughing matter.” Controller Borasus nervously snatched his Key from its slot. “The second code symbol is the one for extreme danger.”

“Oh.” Giraldus stopped laughing. “But, sir, I thought theta-space—”

“—was a new thing the central worlds were playing with?” the Controller finished for him. “So did I. But it looks as if someone knew about it all along.” He shivered slightly. “If I remember rightly, the danger with theta-space is that it can expand indefinitely if it’s not controlled. I’m the Controller,” he added with a nervous laugh. “I have the Key.” He looked down at the Key, hanging from its chain. “It’s possible that this is what the Key is really for.” He pulled himself together and stood up. “I can see it’s no use trusting that idiot Bedford. It will be extremely inconvenient, but I had better get to Earth now and turn the wretched machine off. Notify America, will you? Say I’ll be flying on from London after I’ve been to Hexwood.”

“Yes, sir.” Giraldus made notes, murmuring. “Official robes, air tickets, passport, standard Earth documentation-pack. Is that why I need to know, sir?” he asked, turning to flick switches. “So that I can tell everyone you’ve gone to deal with a classified machine and may be a little late getting to the conference?”

“No, no!” Borasus said. “Don’t tell anyone. Make some other excuse. You need to know in case Homeworld gets back to you after I’ve left. The first symbol means I have to send a report top priority to the House of Balance.”

Giraldus was a pale and beaky man, but this news made him turn a curious yellow. “To the Reigners?” he whispered, looking like an alarmed vulture.

Controller Borasus found himself clutching his Key as if it was his hope of salvation. “Yes,” he said, trying to sound firm and confident. “Anything involving this machine has to go straight to the Reigners themselves. don’t worry. No one can possibly blame you.”

But they can blame me, Borasus thought, as he used his Key on the private emergency link to Homeworld, which no Sector Controller ever used unless he could help it. Whatever this is, it happened in my sector.

The emergency screen blinked and lit with the symbol of the Balance, showing that his report was now on its way to the heart of the galaxy, to the almost legendary world that was supposed to be the original home of the human race, where even the ordinary inhabitants were said to be gifted in ways that people in the colony worlds could hardly guess at. It was out of his hands now.

He swallowed as he turned away. There were supposed to be five Reigners. Borasus had worried, double thoughts about them. On one hand, he believed almost mystically in these distant beings who controlled the Balance and infused order into the Organisation. On the other hand, as he was accustomed to say drily to those in the Organisation who doubted that the Reigners existed at all, there had to be someone in control of such a vast combine, and whether there were five, or less, or more, these High Controllers did not appreciate blunders. He hoped with all his heart that this business with the Bannus did not strike them as a blunder. What – he told himself – he emphatically did not believe were all these tales of the Reigners’ Servant.

When the Reigners were displeased, it was said, they were liable to dispatch their Servant. The Servant, who had the face of death and dressed always in scarlet, came softly stalking down the stars to deal with the one who was at fault. It was said he could kill with one touch of his bone-cold finger, or at a distance, just with his mind. It did no good to conceal your fault, because the Servant could read minds, and no matter how far you ran and how many barriers you put between, the Servant could detect you and come softly walking through anything you put in his way. You could not kill him, because he deflected all weapons. And the Servant would never swerve from any task the Reigners appointed him to.

No, Controller Borasus did not believe in the Servant – although, he had to admit, there were quite frequent dry little reports that came into Albion Head Office to the effect that such-and-such an executive, or director, or sub-consul, had terminated from the Organisation. No, that was something different. The Servant was just folklore.

But I shall take the rap, Borasus thought as he went to get ready to go to Earth, and he shivered as if a blood-red shadow had walked softly on bone feet across his grave.

(#uad1afb1d-a984-5aa1-a6a7-e5ccb7f0016c)

A boy was walking in a wood. It was a beautiful wood, open and sunny. All the leaves were small and light green, hardly more than buds. He was coming down a mud path between sprays of leaves, with deep grass and bushes on either side.

And that was all he knew.

He had just noticed a small tree ahead that was covered with airy pink blossom. He looked beyond it. Though all the trees were quite small and the wood seemed open, all he could see was this wood, in all directions. He did not know where he was. Then he realised that he did not know where else there was to be. Nor did he know how he had got to the wood in the first place. After that, it dawned on him that he did not know who he was. Or what he was. Or why he was there.

He looked down at himself. He seemed quite small – smaller than he expected somehow – and rather skinny. The bits of him he could see were wearing faded purple-blue. He wondered what the clothes were made of and what held the shoes on.

“There’s something wrong with this place,” he said. “I’d better go back and try to find the way out.”

He turned back down the mud path. Sunlight glittered on silver there. Green reflected crazily on the skin of a tall silver man-shaped creature pacing slowly towards him. But it was not a man. Its face was silver and its hands were silver too. This was wrong. The boy took a quick look at his own hands to be sure, and they were brownish-white.

This was some kind of monster. Luckily there was a green spray of leaves between him and the monster’s reddish eyes. It did not seem to have seen him yet. The boy turned and ran quietly and lightly, back the way he had been coming from.

He ran hard until the silver thing was out of sight. Then he stopped, panting, beside a tangled patch of dead briar and whitish grass, wondering what he had better do. The silver creature walked as if it were heavy. It probably needed the beaten path to walk on. So the best idea was to leave the path. Then if it tried to chase him it would get its heavy feet tangled.

He stepped off the path into the patch of dried grass. His feet seemed to cause a lot of rustling in it. He stood still, warily, up to his ankles in dead stuff, listening to the whole patch rustling and creaking.

No, it was worse! Some dead brambles near the centre were heaving up. A long light-brown scaly head was sliding forward out of them. A scaly foreleg with long claws stepped forward in the grass beside the head, and another leg, on the other side. Now the thing was moving slowly and purposefully towards him, the boy could see it was – crocodile? pale dragon? – nearly twenty feet long, dragging through the pale grass behind the scaly head. Two small eyes near the top of that head were fixed upon him. The mouth opened. It was black inside and jagged with teeth, and the breath coming out smelt horrible.

The boy did not stop to think. Just beside his feet was a dead branch, overgrown and half-buried in the grass. He bent down and tore it loose. It came up trailing roots, falling to pieces, smelling of fungus. He flung it, trailing bits and all, into the animal’s open mouth. The mouth snapped on it, and could only shut halfway. The boy turned and ran and ran. He hardly knew where he went, except that he was careful to keep to the mud path.

He pelted round a corner and ran straight into the silver creature.

Clang.

It swayed and put out a silver hand to fend him off. “Careful!” it said in a loud flat voice.

“There’s a crawling thing with a huge mouth back there!” the boy said frantically.

“Still?” asked the silver creature. “It was killed. But maybe we have yet to kill it, since I see you are quite small just now.”

This meant nothing to the boy. He took a step back and stared at the silver being. It seemed to be made of bendable metal over a man-shaped frame. He could see ridges here and there in the metal as it moved, as if wires were pulling or stretching. Its face was made the same way, sort of rippling as it spoke – except for the eyes, which were fixed and reddish. The voice seemed to come from a hole under its chin. But now he looked at it closely, he saw it was not silver quite all over. There were places where the metal skin had been patched, and the patches were disguised with long strips of black and white trim, down the silver legs, round the silver waist and along the outside of each gleaming arm.

“What are you?” he asked.

“I am Yam,” said the being, “one of the early Yamaha robots, series nine, which were the best that were ever made.” It added, with pride in its flat voice, “I am worth a great deal.” Then it paused, and said, “If you do not know that, what else do you not know?”

“I don’t know anything,” said the boy. “What am I?”

“You are Hume,” said Yam. “That is short for human, which you are.”

“Oh,” said the boy. He discovered, by moving slightly, that he could see himself reflected in the robots shining front. He had fairish hair, grown longish, and he seemed to stand and move in a light, eager sort of way. The purple-blue clothes clung close to his skinny body from neck to ankles, without any sort of markings, and he had a pocket in each sleeve. Hume, he thought. He was not certain that was his name. And he hoped the shape of his face was caused by the robots curved front. Or did people’s cheekbones really stick out that way?

He looked up at Yam’s silver face. The robot was nearly two feet taller than he was. “How do you know?”

“I have a revolutionary brain and my memory is not yet full,” Yam answered. “This is why they stopped making my series. We lasted too long.”

“Yes, but,” said the boy – Hume, as he supposed he was, “I meant—”

“We must get out of this piece of wood,” said Yam. “If the reptile is alive, we have come to the wrong time and we must try again.”

Hume thought that was a good idea. He did not want to be anywhere near that scaly thing with the mouth. Yam swivelled himself around on the spot and began to stride back along the path. Hume trotted to keep up. “What have we got to try?” he asked.

“Another path,” said Yam.

“And why are we together?” Hume asked, trying again to understand. “Do we know one another? Do I belong to you or something?”

“Strictly speaking, robots are owned by humans,” Yam said. “These are hard questions to answer. You never paid for me, but I am not programmed to leave you alone. My understanding is that you need help.”

Hume trotted past a whole thicket of the airy pink blossoms, which reflected giddily all over Yam’s body. He tried again. “We know one another? You’ve met me before?”

“Many times,” said Yam.

This was encouraging. Even more encouraging, the path forked beyond the pink trees. Yam stopped with a suddenness that made Hume overshoot. He looked back to see Yam pointing a silver finger down the left fork. “This wood,” Yam told him, “is like human memory. It does not need to take events in their correct order. Do you wish to go to an earlier time and start from there?”

“Would I understand more if I did?” Hume asked.

“You might,” said Yam. “Both of us might.”

“Then it’s worth a try,” Hume agreed.

They went together down the left-hand fork.

(#uad1afb1d-a984-5aa1-a6a7-e5ccb7f0016c)

Hexwood Farm housing estate had one row of shops, all on the same side of Wood Street, and Ann’s parents kept the greengrocer’s halfway down the row. Above the houses on the other side you could see the trees of Banners Wood. And at the end of this row were the tall stone walls and the ancient peeling gate of Hexwood Farm itself. All you could see of the farmhouse was one crumbling chimney that never smoked. It was hard to believe that anybody lived there, but in fact old Mr Craddock had lived there until a few months ago for as long as Ann could remember, keeping himself to himself, and snarling at any child who tried to get close enough to see what was inside the old black gate. “Set the dogs on you!” he used to say. “Set the dogs to bite your leg off!”

There were no dogs, but nobody dared pry into the farm all the same. There was something about the place.

Then, quite suddenly, Mr Craddock was not there and a young man was living there instead. This one called himself Harrison Scudamore and dyed the top of his hair orange. He stalked about with a well-filled wallet bulging the back of his jeans and behaved, as Ann’s dad said, as if he was a cut above the Lord Almighty. This was after young Harrison had stalked into the shop for half a pound of tomatoes and Dad had asked politely if Mr Scudamore was lodging with Mr Craddock.

“None of your business,” young Harrison said. He more or less threw the money at Dad and stalked out of the shop. But he turned in the doorway to add, “Craddock’s retired. I’m in charge now. You’d all better watch it.”

“Awful eyes he has,” Dad remarked, telling Anne and Martin the tale. “Like gooseberries.”

“A snail,” Mum said. “He made me think of a snail.”

Ann lay in bed and thought of young Harrison. She had one of those viruses that was puzzling the doctor, and there was not much to do except lie and think of something. Every so often, she got up out of sheer boredom. Once, she even went back to school. But it always ended with Ann grey and shaky and aching all over, tottering back to bed. And when her brother Martin had been to the library for her, and she had read all her own books, and then Martins – Martin’s were always either about dinosaurs or based on role-playing games – she had no energy to do anything but lie and think. Harrison was at least a new thing to think about. Everybody hated him. He had been rude to Mr Porter the butcher too. And he had told Mrs Price, who kept the newsagent’s at the end, to shut up and stop yakking on. “And I was only talking – politely, you know – the way I do with everyone,” Mrs Price said, almost tearfully. Harrison had kicked the pampered little dog that belonged to the boys who kept the wine shop, and one of them had cried. Everyone had some tale to tell.

Ann wondered why Harrison behaved like that From a project she dimly remembered doing at school, she knew the whole estate had once been lands belonging to Hexwood Farm. The farm stretched north as far as the chemical works and east beyond the motel. Banners Wood, in the middle, had once been huge, though it was hardly even a wood these days. You could see through it to the houses on the other side. It was just trees round a small muddy stream, and all the children played there. Ann knew every crisp packet under every tree root and almost every Coke ring embedded in its muddy paths.

But perhaps Harrison has inherited the farm and thinks he still owns it all, she thought. He did behave that way.

In fact, Ann’s real theory was quite different and much more interesting. That old farm was so secretive and yet so easy to get to from London that she was convinced it was really a hideout for gangsters. She was sure there was gold bullion or sacks and sacks of drugs – or both – stored in its cellar with young Harrison to guard it. Harrison’s airs were because the drug barons paid him so much to guard their secrets.

What do you think about that? she asked her four imaginary people.

The Slave, as so often, was faint and far off. His masters overworked him terribly. He thought the theory very likely. Young Harrison was a menial giving himself airs – he knew the type.

The Prisoner considered. If Ann was right, he said, then young Harrison was behaving very stupidly, drawing attention to himself like this. Her first theory was better.

But I only thought of that to be fair-minded! Ann protested. What do you think, King?

Either could be right, said the King. Or both.

The Boy, when Ann consulted him, chose the gangster theory, because it was the most exciting.

Ann grinned. The Boy would think that. He was stuck on the edge of nowhere, being a sort of assistant to a man who had lived so long ago that people thought of him as a god. He felt out of things, born in the wrong time and place. He always wanted excitement. He said he could only get it through talking to Ann.

Ann was slightly worried about the Boy’s opinions. The Boy was always behaving as if he were real, instead of just an invention of Ann’s. She was a little ashamed of inventing these four people. They had come into her head from goodness knew where when she was quite small and she used to hold long conversations with them. These days she did not speak to them so often. In fact, she was quite worried that she might be mad, talking to invented people, particularly when they took on ideas of their own, like the Boy did. And she did wonder what it said about her – Ann – that all four of her inventions were unhappy in different ways. The Prisoner was always in jail, and he had been put there many centuries ago, so there was no chance of Ann helping him escape. The Slave would be put to death if he tried to escape. One of his fellow-slaves had tried it once. The Slave wouldn’t tell Ann quite what had happened to that slave, but she knew he had died of it. As for the King, he also lived in a far-off time and place, and spent a lot of his time having to do things that were quite intensely boring. Ann was so sorry for all of them that she had often to console herself by keeping firmly in mind the fact that they were not real.

The King spoke to Ann again. He had been thinking, he said, that while Ann was lying in bed she had an ideal opportunity to observe young Harrison’s comings and goings. She might find out something to support her theory. Can you see Hexwood Farm from where you are? he asked.

No, it’s down the street the other way, Ann explained. I’d have to turn my bed round, and I haven’t the strength just now.

No need, said the King. He knew all about spying. All you have to do is to put a mirror where you can see it from your bed, and turn it so it reflects the street and the farm. It’s a trick my own spies often use.

It really was an excellent idea. Ann got out of bed at once and tried to arrange her bedroom mirror. Of course it was wrong the first time, and the second. She lost count of the weak, grey, tottering journeys she made to give that mirror a turn, or a push, or a tip upwards. Then all she saw was ceiling. So off she tottered again. But after twenty minutes of what seemed desperately hard work, she collapsed on her pillows to see a perfect back-to-front view of the end of Wood Street and the decrepit black gate of Hexwood Farm. And there was young Harrison, with his tuft of orange hair, sauntering arrogantly back to the gate carrying his morning paper and his milk. No doubt he had been rude to Mrs Price again. He looked so satisfied.

Thank you! Aim said to the King.

You’re welcome, Girl Child, he said. He always called her Girl Child. All four of her people did.

For a while, there was nothing to watch in the mirror except other people coming and going to the shops, and cars parking in the bay where their owners hauled out bags of washing and took them to the launderette, but even this was far more interesting than just lying there. Ann was truly grateful to the King.

Then, suddenly; there was a van. It was white, and quite big, and there seemed to be several men in it. It drove right up to the gate of the farm and the gate opened smoothly and mechanically to let it drive in. Ann was sure it was a modern mechanism, much more modern than the peeling state of the gate suggested. It looked as if her gangster theory might be right! There was a blue trade logo on the van and, underneath that, blue writing. It was small lettering, kind of chaste and tasteful, and of course in the mirror it was back to front. She had no idea what it said.

Ann just had to see. She flopped out of bed with a groan and tottered to the window where she was just in time to see the old black gate closing smoothly behind the van.

Oh bother! she said to the King. I bet that was the latest load of drugs!

Wait till it comes out again, he told her. When you see the gate open, you should have time to get to the window and see the men drive the vehicle away.

So Ann went back to bed and waited. And waited. But she never saw the van come out. By that evening, she was convinced that she had looked away, or dropped asleep, or gone tottering to the toilet at the moment the gate had opened to let the van out. I missed it, she told the King. All I know is the logo.

And what was that? he asked.

Oh, just a weighing scale – one of those old-fashioned kinds – you know – with two sort of pans hanging from a handle in the middle.

To her surprise, not only the King but the Slave and the Prisoner too all came alert and alive in her mind. Are you sure? they asked in a sharp chorus.

Yes, of course, Ann said. Why?

Be very careful, said the Prisoner. Those are the people who put me in prison.

In my time and place, said the King, those are the arms of a very powerful and very corrupt organisation. They have subverted people in my court and tried to buy my army, and I’m very much afraid that in the end they are going to overthrow me.

The Slave said nothing, but he gave Ann a strong feeling that he knew even more about the organisation than the others did. But they could all be thinking about something else, Ann decided. After all, they came from another time and place from hers. And there were thousands of firms on Earth inventing logos all the time.

I think it’s an accident, she said to the Boy. She could feel him hovering, listening wistfully.

You think that because no one on Earth really believes there are any other worlds but Earth, he said.

True. But you read my mind to know that. I told you not to! Ann said.

I can’t help it, said the Boy. You think we don’t exist either. But we do – you know we do really.

(#uad1afb1d-a984-5aa1-a6a7-e5ccb7f0016c)

Ann forgot about the van. A fortnight passed, during which she got up again and went to school for half a day, and was sent home at lunchtime with a temperature, and read another stack of library books, and lay watching people coming to the shops in her mirror.

“Like the Lady of Shallott!” she said disgustedly. “Fool woman in that fool poem we learnt last term! She was under a curse and she had to watch everything through a mirror too.”

“Oh, stop grumbling, do!” said Ann’s mum. “It’ll go. Give it time.

“But I want it to go now!” said Ann. “I’m an active adolescent, not a bedridden invalid! I’m climbing the walls here!”

“Just shut up and I’ll get Martin to lend you his Walkman,” said Mum.

“That’ll be the day!” said Ann. “He’d rather lend me his cut-off fingers!”

But Martin did, entirely unexpectedly, make a brotherly appearance in her room next morning. “You look awful,” he said. “Like a Guy made of putty.” He followed this compliment up by dropping Walkman and tapes on her bed and leaving for school at once. Ann was quite touched.

That day she lay and listened to the only three tapes she could bear – Martin’s taste in music matched his love of dinosaurs – and kept an eye on Hexwood Farm merely for something to look at. Young Harrison appeared once, much as usual, except that he bought a great deal of bread. Could it be, Ann wondered, that he was really having to feed a vanload of men still inside there? She did not believe this. By now, she had decided, in a bored, gloomy, virusish way, that her exciting theory about gangsters was just silly romancing. The whole world was grey – the virus had probably got into the universe – and even the daffodils in front of the house opposite looked bleak and dull to her.

Someone who looked like a Lord Mayor walked across the road in her mirror.

A Lord Mayor? Ann tore the earphones off and sat up for a closer look. Appa-dappa-dappa-dah, went the music in a tinny whisper. She clicked it off impatiently. A Lord Mayor with a suitcase, hurrying towards the peeling black gate of Hexwood Farm, in a way that was – well – sort of doubtful but determined too. Like someone going to the dentist, Ann thought. And was it a coincidence that the Lord Mayor had appeared just in that early-afternoon lull, when there was never anyone much about in Wood Street? Did Lord Mayors wear green velvet gowns? Or such very pointed boots? But there was definitely a gold chain round the man’s neck. Was he going to the farm to ransom someone who had been kidnapped – with bundles of money in that suitcase?

She watched the man halt in front of the gate. If there was some kind of opening mechanism, it was clearly not going to work this time. After standing there an impatient moment or so, the robed man put out a fist and knocked. Ann could hear the distant, hollow little thumps even through her closed window. But nobody answered the knocking. The man stepped back in a frustrated way. He called out. Ann heard, as distant as the knocking, a high tenor voice calling, but she could not hear the words. When that did no good either, the man put down his suitcase and glanced round the nearly deserted street, to make sure no one was looking.

Ah-haha! Ann thought. Little do you know I have my trusty mirror!

She saw the man’s face quite clearly, narrow and important, with lines of worry and impatience. It was no one she knew. She saw him take up the ornament hanging on his chest from the gold chain and advance on the gate with it as if he were going to use the ornament as a key. And the gate opened, silently and smoothly, just as it had done for the van, when the ornament was nowhere near it. The Lord Mayor was really surprised. Ann saw him start back, and then look at his ornament wonderingly. Then he picked up his suitcase and hurried importantly inside. The gate swung shut behind him. And, just like the van, that was the last Ann saw of him.

This time it could have been because the virus suddenly got worse. For the next day or so, Ann was so ill that she was in no state to watch anything, in the mirror or out of it. She sweated and tossed and slept – nasty short sleeps with feverish dreams – and woke feeling limp and horrible and hot.

Be glad, the Prisoner told her. He had been a sort of doctor before he was put in prison. The disease is coming to a head.

You could have fooled me! Ann told him. I think they kidnapped the Lord Mayor too. That place is a Bermuda triangle. And I’m not better. I’m WORSE.

Mum seemed to share the Prisoner’s opinion, to Ann’s annoyance. “Fever’s broken at last,” Mum said. “Won’t be long now before you’re well. Thank goodness!”

“Only another hundred years!” Ann groaned.

And the night that followed did indeed seem about a century long. Ann kept having dreams where she ran away across a vast grassy park, scarcely able to move her legs for terror of the Something that stalked behind. Or worse dreams where she was shut in a labyrinth made of mother-of-pearl – in those dreams she thought she was trapped in her own eardrum – and the pearl walls gave rainbow reflections of the same Something softly sliding after her. The worst of this dream was that Ann was terrified of the Something catching her, but equally terrified in case the Something missed her in the curving maze. There was blood on the pearly floor of her eardrum. Ann woke with a jump, wet all over, to find it was getting light at last.

Dawn was yellow outside and reflecting yellow in her mirror. But what seemed to have woken her was not the dreams but the sound of a solitary car. Not so unusual, Ann thought fretfully. Some of the deliveries to the shops happened awfully early. Yet it was quite clear to her that this car was not a delivery. It was important. She pulled a soggy pillow weakly under her head so that she could watch it in the mirror.

The car came whispering down Wood Street with its headlights blazing, as if the driver had not realised it was dawn now, and crept to a cautious sort of stop in the bay opposite the launderette. For a moment it stayed that way, headlights on and engine running. Ann had a feeling that the dark heads she could see leaning together inside it were considering what to do. Were they police? It was a big grey expensive car, more a businessman’s car than a police car. Unless they were very high-up police, of course.

The engine stopped and the headlights snapped off. Doors opened. Very high-up, Ann thought, as three men climbed out One was wealthy businessman all over, rather wide from good living, with not a crisp hair out of place. He was wearing one of those wealthy macs that never look creased, over a smart suit. The second man was shorter and plumper, and decidedly shabby, in a green tweed suit that did not fit him. The trousers were too long and the sleeves too narrow, and he had a long knitted scarf trailing from his neck. An informer, Ann thought He had a scared, peevish look, as if he had not wanted the other two to bring him along. The other man was tall and thin, and he was quite as oddly dressed as the informer, in a three-quarter-length little camelhair coat that must have been at least forty years old. Yet he wore it like a king.

When he strolled over to the middle of the road to get a full view of Hexwood Farm, he moved in a curious lolling, powerful way that took Ann’s eyes with him. He had hair the same camelhair colour as his coat. She watched him stand there, long legs apart, hands in pockets, staring at the gate, and she scarcely noticed the other two men come up to him. She kept trying to see the tall man’s face. But she never did see it clearly because they went quickly over to the gate then, with the businessman striding ahead.

Here, it was just like the Lord Mayor. The businessman stopped short, dismayed, as if he had confidently expected the gate to open mechanically for him. When it simply stayed shut, his face turned down to the small informer-man, and this one bustled forward. He did something – tapped out a code? – but Ann could not see what. The gate still did not open. This made the small man angry. He raised a fist as if he was going to hit the gate. At this, the tall man in the camel coat seemed to feel they had waited long enough. He strolled forward, put the informer-man gently but firmly out of the way, and simply went on strolling towards the gate. At the point where it looked as if he would crash into the peeling black boards, the gate swung open, sharply and quickly for him. Ann had a feeling that the stones of the wall would have done that too if the man had wanted it so.

The three went inside and the gate shut after them.

Ann could not rid herself of the feeling that she had just seen the most important thing yet. She expected them to come out quite soon, probably with Harrison under arrest. But she fell asleep still waiting.

(#uad1afb1d-a984-5aa1-a6a7-e5ccb7f0016c)

Much later that morning there was a violent hailstorm. It woke Ann, and she woke completely well again. For a moment, she lay and stared at thick streams of ice running down the window, melting in new, bright sunlight. She felt so well that it stunned her. Then her eyes shifted to the mirror. Through the reflected melting ice, the road shone bright enough to make her eyes water. But there in the parking bay, mounded with white hailstones, stood the businessman’s grey car.

They’re still in there! she thought. It is a Bermuda triangle!

She was getting out of bed as she thought this. Her body knew it was well and it just had to move whether she told it to or not. It had needs. “God!” Ann exclaimed. “I’m hungry!”

She tore downstairs and ate two bowls of cornflakes. Then, while a new hailstorm clattered on the windows, she fried herself bacon, mushrooms, tomatoes and eggs – as much as the pan would hold.

As she was carrying it to the table, Mum hurried through from the shop, alerted by the smell. “You’re feeling better?”

“Oh, I am!” said Ann. “So better that I’m going out as soon as I’ve eaten this.”

Mum looked from the mounded frying pan to the window. “The weather’s not—” But the hail had gone by then. Bright sunlight was slicing through the smoke from Ann’s fry-up and the sky was deep, clear blue. Bang goes Mum’s excuse, Ann thought, grinning as she wolfed down her mushrooms. Nothing had ever tasted so good! “Well, you’re not to overdo it,” Mum said. “Remember you’ve been poorly for a long time. You’re to wrap up warm and be back for lunch.”

“I shall obey, o great fusspot,” Ann said, with her mouth full.

“Lunch, or I shall call the police,” said Mum. “And don’t wear jeans – they’re not nearly warm enough. The weather at this time of year—”

“Fuss-great-potest,” Ann said lovingly, beginning on the bacon. Pity there had been no room in the pan for fried bread. “I’m not a baby. Two layers of thermal underwear satisfy you?”

“Since when have you had–? Oh, I can see you’re better!” Mum said happily. “A vest anyway, to please me.”

“Vests,” Ann said, quoting a badge that Martin often wore, “are what teenagers wear when their mothers feel cold. You’re cold. You keep that shop freezing.”

“You know we have to keep the veg fresh,” Mum retorted, and she went back into the shop laughing.

The sun felt really hot. When she finished eating, Ann went upstairs and dressed as she saw fit: the tight woolly skirt, so that Mum would see she was not wearing jeans, a summery top, and her nice anorak over that, zipped right up so that she looked wrapped up. Then she scudded down and through the shop, calling, “Bye, everyone!” before either of her parents could get loose from customers and interrogate her.

“Don’t go too far!” Dad’s powerful voice followed her.

“I won’t!” Ann called back. Truthfully. She had it all worked out. There was no point trying to work the device that opened that gate. If she tried to climb it, someone would notice and stop her. Besides, if everyone who went into the farm never came out, it would be stupid to go in there and vanish too. Mum and Dad really would throw fits. But there was nothing to stop Ann climbing a tree in Banners Wood and taking a look over the wall from there.

Get a close look at that van, if it’s still there, the King agreed. I’m rather anxious to know who owns it.

Ann frowned and gave a sort of nod. There was something about this weighing-scale logo. It made her four people talk to her when she had not actually started to imagine them. She didn’t like that. It made her wonder again whether she was mad. She went slowly down Wood Street and even more slowly past the expensive car parked in the bay. There were drifts of half-thawed hailstones under it still. As she passed behind it, Ann trailed a finger along the car’s smooth side. It was cold and wet and shiny and hard – and very – very real. This was not just a fever-dream she had imagined in the mirror. She had seen three men arrive here this morning.

She turned down the passage between the houses that led to the wood. It was beautiful down there, hot and steamy. Mum and her vests! Melting hailstones flashed rainbow colours from every blade of grass along the path. And the wood had gone quite green while she had been in bed – in the curious way woods do in early spring, with the bushes and lower branches a bright emerald thickness, while the upper boughs of the bigger trees were still almost bare, and only a bit swollen in their outlines. It smelt warm, and keen with juices, and the sunlight made the green transparent.

Ann had walked for some minutes in the direction of the farm wall when she realised there was something wrong with the wood. Not wrong exactly. It still stretched around her in peaceful arcades of greenness. Birds sang. Moss grew shaggy on the path under her trainers. There were primroses on the bank beside her.

“Here, wait a minute!” she said.

The paths in Banners Wood were always muddy, with Coke rings trodden into them. And if a primrose had dared show its face there, it would have been picked or trampled on the spot. And she should have reached the farm wall long ago. Even more important, she should have been able to see the houses on the other side of the trees by now.

Ann strained her eyes to where those houses should have been. Nothing. Nothing but trees or green springing hawthorn and, in the distance, a bare tree carrying load upon load of tiny pink flowers. Ann took the path towards that tree, with her heart banging. Such a tree had never been seen in Banners Wood before. But she told herself she was mistaking it for the pussy willow on the other side of the stream.

She knew she was not, even before she came up beside the big leaden-looking container half-buried in the bank beyond the primroses. She could see far enough from beside this container to know that the wood simply went on, and on, and on, beyond the pink tree. She stopped and looked at the container. People often did throw rubbish in the wood. Martin had had wonderful fun with an old pram someone had dumped here. This thing looked as if someone had thrown away a whole freezer – one of the big kind like a chest with a lid. It had been there a long time. Not only was it half-buried in the bank. Its outside had rotted and peeled to a dull grey. Wires came out of it in places, rusty and broken. It looked – well – not really like a freezer, quite.

Mum’s voice rang warnings in Ann’s ears. “It’s dirty – you don’t know where it’s been – something could be rotting inside it – it could be nuclear!”

It did look like a nuclear-waste container.

What do you think? Ann asked her four imaginary friends.

To her great surprise, none of them answered. She had to imagine their voices replying. The Boy would say, Open it! Take a look! You’d never forgive yourself if you didn’t. She imagined the others agreeing, but more cautiously, and the King adding, But be careful!

Maybe it was the solution to the Hexwood Farm mystery – the thing that had fetched all those men to call on young Harrison, the thing he thought so well of himself for guarding. Ann scrambled up the bank, put the heels of her hands firmly into the crack under the lid of the container, and heaved. The lid sprang up easily, and then went on rising of its own accord until it was standing upright at the back of the box.

Ann had not expected it to be that easy. It sent her staggering back down the bank to the path. There, she looked at the open container and could not move for sheer terror.

A corpse was rising up out of it.

The head appeared first, a face that looked like a skull except for long straggles of yellow-white hair and beard. Next, a hand clutched the edge of the box, a hand white-yellow with enormous bone knobs of knuckles and – disgustingly – inch-long yellow fingernails. Ann gave a little whimper at this, but still she could not move. Then there was heaving. A gaunt bone shoulder appeared. Breath whistled from the lips of the skull. And the corpse dragged itself upright, unfolding a long, long body grown all over with coarse tangles of whitish hair. Absolutely indecent! Ann thought, as the long spindly legs rose above her, shaking, and shaking loose the fragments of rotted cloth wound round the creature’s loins. It was very weak, this corpse. For an instant, Ann saw it as almost pathetic. And it was not quite a skeleton. Skin covered it, even the face, which was still far too like a skull for comfort.

The face turned. The eyes, large, sunk and pale under a grey-yellow hedge of eyebrow, looked straight at Ann. The skull lips moved. The thing said something – croaked something – words in a strange language.

It had seen her. It was too much. It spoke. Ann ran. She scrambled into a turn and ran, and her hurtling trainers slipped beneath her. She was down on the moss of the path, hardly aware of the sharp stone that met her knee, up again in the same breath, and running as fast as her legs could take her, away down the path. A corpse that walked, looked, spoke. A vampire in a lead chest – a radioactive vampire! She knew it was coming after her. Fool to keep to the path! She veered up the bank and ran on, crunching and galloping on squashy lichen, leaping among brambles, tearing through strident green thickets, with dead branches cracking and exploding under her feet. Her breath screamed. Her chest ached. She was ill. Fool. She was making so much noise. It could follow her just by listening.

“What shall I do – what shall I do?” she whimpered as she ran.

Her legs were giving way. After all that time in bed she was almost as weak as the vampire-thing. Her left knee hurt like crazy. She glanced down as she crashed through some flat brown briars to see bright red blood streaming down her shin and into her sock. There was blood in the brambles she stood in. It could track her by smell too.

“What shall I do?”

The sensible thing was to climb a tree.

“Oh, I couldn’t!” Ann gasped.

The creature croaked again, somewhere quite near.

Ann found strength she did not know she had. It sent her to the nearest climbable tree and swarming up it like a mad girl. Bark bit the insides of her legs. Her fingers scraped and clawed, breaking most of the fingernails she had been so proud of. She heard her nice anorak tear. But still she climbed, until she was able to thrust her head through a bush of smaller branches and scramble astride a strong bough, safe and high, with her back against the trunk and her hair raked into hanks across her face.

If it comes up, I can kick it down! she thought, and leant back with her eyes shut.

It was croaking somewhere below, even nearer, to her right.

Ann’s eyes sprang open. She stared down in weak horror at the path and the chest embedded in the bank beyond it. The lid had shut again. But the creature was still outside it, standing in the path almost below her, staring down at the scarlet splatter of blood Ann’s knee had made when she fell on the stone. She had run in a circle like a panicked animal.

Don’t look up! Don’t look up! she prayed, and kept very still.

It did not look up. It was busy examining its taloned hands, then putting those hands up to feel the frayed bush of its hair and beard. Ann got the feeling it was very, very puzzled. She watched it take hold of the shreds of cloth wrapped round its skinny hips and pull off a piece to look at. It shook its head. Then, in a mad, precise way, it laid the strip of rag across its left shoulder and croaked out some more words. This time, the sound was less of a croak and more like a voice.

Then – despite all the rest, Ann still had trouble believing her eyes – the creature grew itself clothes. The lower rags went expanding downwards in two khaki waterfalls of thick cloth, to make narrow leggings and then brown supple-looking boots. At the same time the strip of rag on the corpse’s shoulder was chasing downwards too, tumbling and spreading into a calf-length robe-thing, wide and pleated, the colour of camelhair. Ann’s lips parted almost in an exclamation as she saw the colour. She watched, then, almost as if she expected it, the long hair and beard turn the same camelhair colour and shrink away. The beard shrank right away into the man’s chin, leaving his face more skull-shaped than ever, but the hair halted just below his ears. He completed himself by strapping a broad belt round his waist – it had a knife and a pouch attached to it – and slinging a sort of rolled blanket across his left shoulder, where he carefully fastened it with straps. After that, he gave a mutter of satisfaction and went to the edge of the path, where he drew the knife and cut himself a stout stick from the tree nearest the leaden chest.

Even before he moved, Ann was nearly sure who he was. The long strolling strides with which he walked across the path made her quite certain. He was the tallest of the three men who had come in that car, the one who had made the gate open, the one in the odd camelhair coat. He was still wearing that coat, after a fashion, she thought, except he had made it into a robe.

He came back to the path, carrying the stick. It was no longer a stick, but a staff, old and polished and carved with curious signs. He looked up at Ann and croaked out a remark at her.

She recoiled against the tree trunk. Oh my God! He knew I was there all along! And now she was the indecent one. Comes of climbing trees in a tight skirt. The skirt was rolled up round her waist. He must be looking straight up at her pants. And her long, helpless legs dangling down on either side of the branch.

The strange man below coughed, displeased with his voice, still staring up at Ann. His eyes were light, inside deep hollows. His eyebrows met over his nose, in one eyebrow shaped like a hawk flying. He was a weird-looking man, even if you met him in the ordinary way, walking down the street. You’d think, Ann thought, you’d run into the Grim Reaper.

“I’m sorry,” she said, high-voiced with fear. “I – I can’t understand a word you’re saying – and I don’t want to.”

He looked startled. He thought. Gave another cough. “I apologise,” he said. “I was using the wrong language. What I said was, I’ve no intention of hurting you. Won’t you come down?”

They all say that! Mum’s warning voice said in Ann’s head. “No, I won’t,” Ann said. “And if you try to climb up I shall kick you.” And she wondered frantically, How do I get out of this? I can’t sit up here all day!

“Well, do you mind if I ask you a few questions?” asked the man. As Ann drew breath to say that she did mind, very much, he added quickly, “I’ve never been so puzzled in my life. What is this place?”

Now he was getting used to talking, he had quite a pleasant deep voice, with a slight foreign accent. Swedish? Ann wondered. And he did have every reason to be puzzled. There seemed no harm in telling him what little she knew. “What do you want to ask?” she said cautiously.

He cleared his throat again. “Can you tell me where we are? Where this is?” He gestured round at the green distances of the wood.

“Well,” Ann said, “it ought to be the wood just beside Hexwood Farm, but it – seems to have gone bigger.” As he seemed quite bewildered by this, she added, “But it’s no use asking me why it’s bigger. I can’t understand it either.”

The man clicked his tongue and stared up at her impatiently. “I know about that. I could feel I was working with a field just now. Something near by is creating a whole set of paratypical extensions—”

“You what?” said Ann.

“You’d probably call it,” he said thoughtfully, “casting a spell.”

“I would not!” Ann said indignantly. She might look absurd and indecent sitting dangling in this tree, but that didn’t mean she was a moron! “I’m far too old to think anything so silly.”

“Apologies,” he said. “Then perhaps the best way to explain it is as quite a large hemisphere of a certain kind of force that has power to change reality. Does that help you?”

“Sort of” Ann admitted.

“Good,” he said. “Now please explain where and what is Hexwood Farm.”

“It’s the old farm on our housing estate,” Ann said. He looked bewildered again. The one eyebrow gathered in over his nose, and he leant on his staff to stare about him. Ann thought he seemed wobbly and ill. Not surprising. “It’s not a farm any more, just a house,” she explained. “About forty miles from London.” He shook his head helplessly. “In England, Europe, Earth, the solar system, the universe. You must know!” Ann said irritably. “You came here in a car this morning. I saw you – going into the farm with two other men!”

“Oh no,” he said, sounding faint and tired. “You’re mistaken. I’ve been in stass-sleep for centuries, for breaking the Reigners’ ban.” He turned and pointed a startlingly long finger at the chest half-buried in the bank. “Now you have to believe that. You were standing here, where I am now, when I came out. I saw you.”

This was hard to deny, but Ann was sure enough of her facts to try, leaning earnestly down from her branch. “I know – I mean, I did see you – but I saw you before that, early this morning, walking in the road in modern clothes. I swear it was you! I knew by the way you walked.”

The man below firmly shook his head. “No, it was not me you saw. It must have been a descendant of mine. I took care to have many descendants. It was – was one good way of breaking – that unjust ban.” He put a hand to his forehead. Ann could see he was coming over queer. The staff was wobbling under his hand.

“Look,” she said kindly, “if this – this sphere of force can change reality, couldn’t it have changed you, like it changed the wood?”

“No,” he said. “There are some things that can’t be changed. I am Mordion. I am from a distant world and I was sent here under a ban.” He used his staff to help him to the bank, where he sat down and covered his face shakily with one hand.

It reminded Ann of the weak way she had felt only yesterday. She was torn between sympathy for him and urgent worry about herself. Probably he was not sane. And her legs were going numb and needlish, the way legs do if they are left to dangle. “Why don’t you,” she said, thinking of the way she had wolfed down that pan of food, “get the force to change reality and sent you something to eat? You must be hungry. If I’m right, you haven’t eaten anything since it got light this morning. If you’re right, you must be bloody ravenous!”

Mordion brought his skull of a face out of his hand. “What sound sense!” He raised his staff, then paused and looked up at Ann. “Would you like some food too?”

“No thanks. I have to be home for lunch,” Ann said primly. While he was eating his boars head, or whatever he got his thingummy field to send him, Ann was planning to slide down this tree and run – run like mad, in a straight line this time.

“As you please.” Mordion made a sharp, angular gesture with his staff. Before he had half completed the movement, something square and white was following the gesture in the air. He brought the staff down in a smooth arc and the square thing glided down with it and landed on the bank. “Hey presto!” Mordion said, looking up at Ann with a large smile.

Ann quite forgot to slide down the tree. The square thing was a plastic tray divided into compartments and covered with transparent film. That was the first amazing thing. The second amazing thing was that some of the food inside was bright blue. The third and most amazing thing, which really held Ann riveted to her branch, was that smile Mordion gave her. If a skull smiles, you expect something mirthless, with too many teeth in it. Mordion’s smile was nothing like that. It was full of amusement and humour and friendship. It was glowing. It changed his face to something that made Ann’s breath catch. She felt almost weak enough, seeing it, to topple off her branch. It was the most beautiful smile she had ever seen.

“It’s – that’s aeroplane food!” she said, and felt her face going red because of that smile.

Mordion stripped the transparent top off the tray. Steam rose into the dappled sunlight, and so did a most appetising smell. “Not really,” he said. “It’s a stass-tray.”

“What’s the blue stuff?” Ann could not help asking.

“Yurov keranip,” he answered. His mouth was full of it. He had detached a spoon-thing from the side of the tray and was eating as if it was indeed centuries since he last ate. “A sort of root,” he added, fetching a bread roll out and using it to help the spoon-thing. “This is bread. The pinkish things are collops from Iony in barinda sauce. The green is – I forget – a kind of seaweed, I think, fried, and the yellow is den beans in cheese. Underneath, there should be a dessert. I hope so, because I’m hungry enough to eat the tray if there isn’t. I might spare you a taste if you care to come down, though it would be a wrench.”

“No thanks,” Ann said. But since her legs were going really numb, she struggled one knee on to the branch and managed to pull herself up until she was standing, leaning against the tree trunk, with one arm draped comfortably over a higher branch. Like that, she could wriggle her skirt back down and feel almost respectable. The blood still streaked down her shin, but it was brown and shiny by then.

There was a dessert under the hot food. Ann watched, slightly wistfully, as Mordion lifted the top tray out as you do with a box of chocolates. Underneath, it looked like ice cream, as mysteriously cold as the top course was hot. I am in a field of paratypical thingummies, Ann thought. Anything is possible. That ice cream looked luscious. There was a cup of hot drink beside it.

Mordion tossed the spoon into the empty trays and took the cup in both hands. “Ah,” he said, supping comfortably. “That’s better. Now, I want to ask you something else. But, first, what’s your name?

“Ann,” said Ann.

He looked up at her, puzzled again. “Really? I thought – somehow – it would be a longer name than that.”

“Ann Stavely, if you insist,” said Ann. She was certainly not going to tell him that her middle name was, hatefully, Veronica.

Mordion bowed to her over his steaming cup. “Mordion Agenos. This is what I want to ask you – will you help me to make another attempt to break the Reigners’ ban?”

“It depends,” Ann said. “What are rainers?”

“Those who rule,” said Mordion. His face set into the grimmest of deaths-heads. Above the steaming cup it looked terrible, particularly surrounded by the bright spring woodland, full of the green of life and the chirping of nesting birds. “There are five of them and, though they live light years across the galaxy, they rule every inhabited world, including this one.”

“What – even inside this thingummy field?” Ann asked.

Mordion thought. “No,” he said. “No. I am almost sure not. This seems to be one reason why it came into my head to try to break their ban again.”

“Are the Reigners very terrible?” Ann asked, watching his face.

“Terrible?” Mordion said. She saw hatred and horror working under his grimness. “That’s too small a word. But yes. Very terrible.”

“And what’s this ban they put on you?”

“Exile. And I am not to go against the Reigners in any way.” Looking up at her from under his long wings of eyebrow, Mordion had a sinister unearthliness. Ann shivered as he said, “You see, I’m of Reigner blood too. I could defeat them if I was free. I nearly did, twice, long ago. That was why they put me in stass.”

But that’s not true! Ann thought. Humour him, or I’ll never get out of this tree. “So how do you want me to help?”

“Give me permission to make use of your blood,” Mordion said.

“What?” Ann backed against the trunk of the tree, and pressed further against it when Mordion pointed to the place in the path where she had fallen over. It had not dried up like the blood on her leg. Down there it was bright red and moist. There seemed to be an awful lot of it too, spreading luridly among the green mosses and splashed scarlet on the white stone that had cut her. It looked almost as if something had been killed there.

“The field is waiting to work with it,” Mordion told her. “It was the first thing I noticed after you ran away.”

“What for? How?” Ann said. “I don’t agree to anything!”

“Perhaps if I explain.” Mordion stood up and strolled over to a spot just under Ann’s branch. She felt sick, and tried to back even further. She could see the buds on the end of her branch shaking in front of Mordion’s upturned face. She felt as if she was making the whole tree shake. “What was done in the past,” Mordion said, “was to get round the Reigners’ ban by breeding a race of men and women who were not under the ban and could go against the Reigners—”

“I’m not doing that!” Ann almost screamed.

“Of course not.” Mordion smiled. The smile was brief and sad, but as wonderful as before. “I’ve learnt my lesson there. It took far too long, and it ended in misery. The Reigners eliminated the first race of people. The second time there were too many to kill, so they killed the best and put me in stass so that I was not there to guide the others. There must be hundreds of their descendants now with Reigner blood, here in this world. You, for instance. That’s what the paratypical field is showing us.” He pointed once more to the bright blood in the path.

In spite of her fear and disgust and complete disbelief, Ann could not help a twinge of pride that her blood was so special. “So what do you want it for this time?”

“To create a hero,” said Mordion, “safe from the Reigners inside this field, who is human and not human, who can defeat the Reigners because they will not know about him until it is too late.”

Ann thought about it – or, to be truthful, let her head fill with a mixed hurry of feelings. Disbelief and fear mixed with a terrible sadness for Mordion, who thought he was trying the same useless thing for a third time; and horror, because Mordion just might be right; while underneath ran urgent, ordinary, homely feelings, telling her she really did have to be back for lunch. “If I say yes,” she said, “you can’t touch me and you have to let me go home safe straight afterwards.”

“Agreed.” Mordion looked earnestly up at her. “You agree?”

“Yes, all right,” Ann said, and felt the most terrible coward saying it But what could she do, she asked herself, stuck up in a tree in a place where everything was mad, with Mordion prowling round its roots?

Mordion smiled at her again. Ann was lapped in the sweetness and friendliness of it and weakened in her already wobbly knees. But a small clinical piece of her said, he uses that smile. She watched him turn and stroll to the patch of blood, with his pleated robe swinging elegantly round him, and wondered how he thought he would create a hero. His knife was in his right hand. It caught the green woodland light as he made a swift, expert cut in the wrist of his other hand that was holding his staff. Blood ran freely, in the same unexpected quantity as Ann’s.

“Hey!” Ann said. Somehow she had not expected this.

Mordion did not seem to hear her. He was letting his blood trickle down his staff, round and among the strange carvings on it, guiding the thick flow to drip off the wooden end and mingle with Ann’s blood on the path. He was certainly also working on the paratypical field. Ann had a sense of things pulsing, and twisting a little, just out of sight.

Mordion finished and stood back. Everything was still. Not a tree moved. No birds sang. Ann was not sure she breathed.

A strange welling and mounding began on the path, on either side of the patch of blood. Ann had seen water behave that way when someone had thrown a log in deep and the log was rising to the surface. She leant forward and watched, still barely breathing, moss and black earth, stones and yellow roots pouring up and aside to let something rise up from underneath. There was a glimpse of white, bone white, about four feet long, and a snarl of what looked like hair at one end. Ann bit her lip till it hurt. Next second, a bare body had risen, lying face downwards in a shallow furrow in the path. A fairly small body.

“You must give him clothes,” she said, while she waited for the body to grow.

Out of the corner of her eye, she saw Mordion nod and move his staff. The body grew clothes, the same way as Mordion had done, in a blue-purple flush spreading over the dented white back and thickening into what looked like a tracksuit. The bare feet turned grey and became feet wearing old sneakers. The body squirmed, shifted, and propped itself up on its elbows, facing down the path away from both of them. It had longish draggly hair the same camel colour as Mordion’s.

“Bump. Fell,” the body remarked in a high clear voice.

Then, obviously assuming he had tripped and fallen in the path, the boy in the tracksuit picked himself up and trotted out of sight beyond the pink blossoming tree.

Mordion stood back and looked up at Ann. His face had dragged into lines. Making the boy had clearly tired him out. “There, it’s done,” he said wearily, and went to sit among the primroses again.

“Aren’t you going to go after him?” Ann asked.

Mordion shook his head.

“Why not?” said Ann.

“I told you,” Mordion said, very tired, “that I learnt my lesson there. It’s between him and the Reigners now, when he grows up. I shall not need to appear in it.”

“And how long before he grows up?” Ann asked.

Mordion shrugged. “I’m not sure how time in this field relates to ordinary time. I suppose it will take a while.”

“And what happens if he goes out of the parathingummy field,” Ann demanded, “into real time?”

“He’ll cease to exist,” said Mordion, as if it were obvious.

“Then however is he supposed to conquer these Reigners? You told me they live light years away,” Ann said.

“He’ll have to fetch them here,” said Mordion. He lay back on the bank, looking worn out.

“Does he know that?” Ann demanded.

“Probably not,” Mordion said.

Ann looked down at him, spread on the bank preparing to go to sleep, and lost her temper. “Then you should go and tell him! You should look after him! He’s all alone in this wood, and he’s quite small, and he doesn’t even know he’s not supposed to go out of it. He probably doesn’t even know how to work the field to get food. You – you calmly make him up, out of blood and – and nothing, and you expect him to do your dirty work for you, and you don’t even tell him the rules! You can’t do that to a person!”

Mordion rose up on one elbow. “The field will take care of him. He belongs to it. Or you could. He’s half yours, after all.”

“I have to go home for lunch!” Ann snarled. “You know I do! Is there anyone else in this wood who could take care of him?”

Mordion was getting that look Dad had when Ann went on at him. “I’ll see,” he said, clearly hoping to shut her up. He sat up and raised his head in a listening way, turning slowly from left to right. Like radar operating, Ann thought. “There are others here,” he said slowly, “but they are a long way off and too busy to be spared.”

“Then get the field,” said Ann, “to make another person.”

“That,” said Mordion, “would take more blood – and that person would be a child too.”

“Then someone who isn’t real,” insisted Ann. “I know the field can do it. This whole wood isn’t real. You’re not real—”

She stopped, because Mordion turned and looked at her. The pain in his look almost rocked her backwards.

“Well, only half real,” she said. “And stop looking at me like that just because I’m telling you the truth. You think you’re a magician with godlike powers, and I know you’re just a man in a camelhair coat.”

“And you,” said Mordion, not quite angry, but getting that way, “are very brave because you think you’re safe up a tree. What makes you think my godlike powers can’t fetch you down?”

“You can’t touch me,” Ann said hastily. “You promised.”

The earlier grim look came back into Mordion’s face. “There are many ways,” he said, “to hurt a person without touching them. I hope you never find out about them.” He stared into grim thoughts for a while, with his eyebrow hooked above his strange flat nose. Then he sighed. “The boy is fine,” he said. “The field has obeyed you and produced an unreal person to care for him.” He lay back on the bank again and arranged the rolled blanket-thing at his shoulder as a pillow.

“Really?” said Ann.

“The field doesn’t like you shouting at it any more than I do,” Mordion replied sleepily. “Get down from your tree and go in peace.”

He rolled on his side and seemed to go to sleep, a strange bleached heap huddled on the bank. The only colour about him was the red gash on his wrist, above the hand clutching his staff.

Ann waited in her tree until his breathing was slow and regular and she was sure he was really asleep. Only then did she go round to the back of the tree and slide down as quietly as she knew how. She got to the path with long tiptoe strides and sprinted away down it, still on tiptoe. And she was still afraid that Mordion might be stealing after her. She looked back so frequently that after fifty yards she ran into a tree.

She met it with a bruising thump that seemed to shake reality back into place. When she looked forward, she found she could see the houses on the near side of Wood Street. When she looked backwards to check, she could see houses again, beyond the usual sparse trees of Banners Wood. And there was no sign of Mordion among them.

“Well, that’s that then!” she said. Her knees began to shake.

(#uad1afb1d-a984-5aa1-a6a7-e5ccb7f0016c)

(#uad1afb1d-a984-5aa1-a6a7-e5ccb7f0016c)