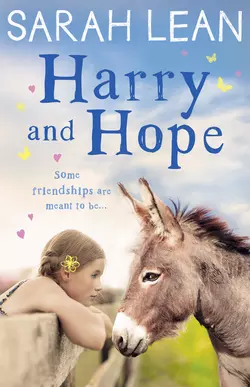

Harry and Hope

Sarah Lean

Some friendships are meant to be… A story about family, friendship and belonging, from bestselling author, Sarah Lean.Hope lives with her artist mum in the Pyrenees. It’s always been just the two of them… until Frank – a free-spirited traveller – arrives with his donkey, Harry.Hope and Frank form a close bond, so it’s hard for both of them when Frank decides it’s time to move on. Hope questions what she is to Frank. He’s not her dad, but he was more than just her mum’s boyfriend. Except, there’s no name for that kind of pair…Hope promises to look after Harry and, slowly, another special pair is made – one that makes Hope realise that some friendships become part of you and, even when someone is far away, they are always near to your heart.

Copyright (#uf27b165c-17f4-558c-a97c-e76aa4aac4d5)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2015

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

Copyright © Sarah Lean 2015

Illustrations © Gary Blythe 2015

Cover photographs © Mark harris (dog), Cavan images / Getty images (boy), Shutterstock (all other images)

Sarah Lean asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of the work.

Gary Blythe asserts the moral right to be identified as the illustrator of the work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007512263

Ebook Edition © 2015 ISBN: 9780007512256

Version: 2015-02-05

Praise for Sarah Lean (#uf27b165c-17f4-558c-a97c-e76aa4aac4d5)

“Sarah Lean weaves magic and emotion into beautiful stories.”

Cathy Cassidy

“Touching, reflective and lyrical.”

The Sunday Times

“… beautifully written and moving. A talent to watch.”

The Bookseller

“Sarah Lean’s graceful, miraculous writing will have you weeping one moment and rejoicing the next.”

Katherine Applegate, author of The One and Only Ivan

For my little sister

Contents

Cover (#u067e440f-8f5a-5399-a5aa-65ba4d5b86ba)

Title Page (#u0f192faf-33f2-5a4c-8741-6ba25c67cd63)

Copyright

Praise for Sarah Lean

Dedication (#u8f144424-3392-5bb8-a264-863594ac8878)

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Sarah Lean

About the Publisher

(#uf27b165c-17f4-558c-a97c-e76aa4aac4d5)

It must have snowed on the mountain in the night.

“Have you seen it yet, Frank?” I shouted downstairs.

“You mean did I hear?”

“I know, funny, isn’t it? The snow’s so quiet but it’s making all the animals noisy.”

We didn’t normally see snow on Canigou in May, and it made the village dogs bark in that crazy way dogs do when something is out of place. Harry, Frank’s donkey, was down in his shed, chin up on the half open door, calling like a creaky violin.

Frank came up to the roof terrace where I’d been sleeping in the hammock. He leaned over the red tiles next to me and we looked at Canigou, sparkling at the top like a jewellery shop.

And it’s the kind of thing that is hard to describe, when snow is what you can see while the sun is warming your skin. How did it feel? To see one thing and feel the complete opposite? I only knew that other things didn’t seem to fit together properly at the moment either; that my mother and Frank seemed as far apart as the snow and the sun.

“Frank, at school Madame was telling us that the things we do affect the environment, you know, like leaving lights on, things like that,” I said. “Well, I left the lights on in the girls’ loo.”

Frank smiled. Frank was my mother’s boyfriend, but that won’t tell you what he meant to me at all. He’d lived in our guesthouse next door for three years and he wouldn’t ever say the things to me that Madame had said when I forgot to turn the lights off. In fact, what he did was leave a soft friendly silence, so I knew I could ask what I wanted to ask, because I wasn’t sure about the whole environment thing.

“Did I make it snow on Canigou?”

“Leave the light on and see if it snows again,” he whispered, grinning.

He made the world seem real simple, like a little light switch right under my fingertips. But there were other complicated things.

“Remember when the cherry blossom fell a few weeks ago?” I said.

He nodded.

“How many people do you think have seen pink snow?”

“Only people who see the world like you.”

“And you.”

I looked out from all four corners of the terrace.

South was the meadow, and then the Massimos’ vineyards that belonged to my best friend Peter’s family – lines and lines of vines curving over the steep mountainside, making long lazy shadows across the red soil paths. I thought of the vines with their new green leaves twirling along the gnarly arms, reaching out to curl around each other, like they needed to know they weren’t alone; that they’d be strong enough together to grow their grapes.

North were the gigantic plane trees with big roots and trunks that cracked the roads and pavements around the village.

East was the village, the roofs of the houses stacked on the mountainside like giant orangey coloured books left open and abandoned halfway through a story.

West were the cherry fields, and Canigou, the highest peak that we could see in the French Pyrenees. It soared over the village and the vineyards, high above us.

I touched the things I kept in the curve of the roof tiles, the wooden things Frank had carved for me. I whispered their names and picked them up, familiar, warm and softly smooth in my hands: humming bird, the letter H, mermaid, donkey, cherries, and the latest one – the olive tree knot made into a walking-stick handle that Frank said I might need to lean on to go around the vineyards with Peter when we’re ninety-nine. Always in that order. The order that Frank made them.

“What you thinking about, Frank?”

“The world,” he said quietly. “And cherry blossom.”

When you’re twelve, it takes a long time for the different sounds and words you’ve heard and the things you’ve seen to end up some place deep inside of you where you can make sense of them. It was that morning when I worked out what my feelings had been trying to tell me; when I saw Frank looking at our mountain like he was remembering something he missed; when I saw the passport sticking out of his pocket.

It felt like even the crazy dogs had known before me, as if even the mountain had been listening and watching and trying to tell me.

Frank looked over.

“Spill,” he said, which is what he always said when he knew there were words swirling inside me that I couldn’t seem to get out.

“Why did you travel all around the world, Frank? I mean, you went to loads of different countries for twenty years before you came here, and that’s, like, a really, really long time to be travelling.”

“Something in me,” he said.

“But you don’t need to go travelling again, do you?”

For three whole years my mother and I had been more than the rest of the world to him.

He looked down at his pocket, knew what I had seen. Tilted his leather hat forward to shade his eyes.

“What I mean is…” I didn’t know exactly how to explain. A boyfriend was somebody for my mother. For me, it used to be a person who picked me up and swirled me around and bought me soft toys which, after a while, I binned because the person who bought them always left. But that wasn’t what Frank did. There wasn’t a word for what Frank was to me. I mean, how can you explain something when there isn’t even a word for it? I just wanted to ask: if he was thinking about leaving, what about me? How would we still fit together?

“What I mean is…” I tried again. “Say you like cherries, which I do, and then you eat them with almonds, which I also like a lot… you get something else, right? Something that makes the cherries more cherry-ish and the almonds more kind of almond-y.”

“Like tomatoes and basil?” Frank said. His favourite.

Down below us, Harry kicked at his door. And Harry… well, you couldn’t have Frank without Harry. They were definitely as good together as yoghurt and honey.

“Yes, like that,” I said. “But also you and Harry, Mum and you, you know, there’s these kinds of pairs of us.”

“You and Peter?”

“Yeah, us too. These pairs you made of us.” I picked the little wooden donkey up, turned it in my hands. “I feel kind of smoother, and sort of… more, when we’re together.” That’s what I felt about me and Frank. “I’m kind of more me when you’re around.”

“Hope Malone,” he said. “You have your own things that are just you.”

I said, “But I’d be just half of me without you.”

Frank pushed his passport deeper into his pocket.

“Are you planning on going somewhere, Frank?”

“We’ll talk later,” he said as Harry’s hoof clattered against his shed again. “I’d better let that donkey out before he kicks the door down.”

(#uf27b165c-17f4-558c-a97c-e76aa4aac4d5)

Anybody would love Harry straight away. As soon as you put your hand out to touch him and he greeted you in his nuzzly donkey kind of way, he made you feel so nice. He was only little, about as high as my waist, with stick spindly legs, but round where there was much more of him in the middle. I always thought he was a bit shy, the way his eyelashes curled up and the fact that he never looked you in the eye. He seemed to hear everything Frank said, though, like the words poured down his tall ears and into his whole skin and bones and barrelled belly.

“Going somewhere?” Frank said, as Harry barged out of his shed, quivering with happiness just because Frank spoke to him. Harry trotted straight over to the trailer hitched to the back of Frank’s dusty jeep.

“Where are you going?” I asked.

“Same as always,” Frank said.

I mean, I knew where they were going because they always did the same thing every day. Frank would have to drive Harry along the lane and back again before Harry would go down to the meadow. It was an old habit of Harry’s from their travelling days years ago. If they didn’t go for a spin with the jeep and trailer, Harry wouldn’t go down to the meadow, no matter how big the carrot you held in front of his nose was. I completely got it, why Harry had to have things as they always were. Frank had rescued Harry and brought him over from India. Harry was safe, getting in the trailer every day and not going back to how his awful life was.

Same as always. But what about Frank’s passport?

I watched them go before running back up to the roof to get dressed.

Marianne was up there with her camera, taking photographs of Canigou.

Everyone called my mother Marianne, even me most of the time. She was an artist. Her bedroom and studio, where she’d normally be, were on the first floor next to each other. She usually stayed there most of the day and didn’t come out into the world if she didn’t want to. We weren’t allowed to go and disturb her either.

“The cherry blossom’s all gone,” she said.

“It’s been gone ages.”

“Oh, I hadn’t noticed.”

I coughed. “Excuse me, I want to get dressed.”

“I’m not looking,” she said, turning the camera towards Canigou. “Why are you sleeping up here anyway?”

As soon as it was warm enough I had wanted to sleep outside, so that if I woke up, I would see the dark shape of the mountain between the stars, even on the blackest night. I didn’t say that though, because I couldn’t talk to her about things like that. I couldn’t have just burst into her space and told her that the blossom was falling and it was so beautiful I might explode. There’s only that one moment when you feel like that and then it’s gone, and these things I wanted to say didn’t ever seem to fit with Marianne at the right time. So I’d gone and told Frank and he’d stood and watched with me and there was nothing left to say anyway, because Frank and I were the same, all filled up with that blustery breeze making pink snow of the blossom.

“It’s too hot in my bedroom,” I said, rummaging under the blankets drooping over the hammock and on to the floor. “I can’t find my shoes.”

“Where are the new ones I bought you?”

I shrugged.

“In your other bedroom, probably still in the box,” said Marianne.

I took my clothes downstairs and got changed. I grabbed my new shoes from the box in my room and a croissant from the kitchen and went outside with the croissant in my mouth to wait for Harry and Frank.

When they got back, Harry trotted out of the trailer, looked around, and Frank frowned and said to him, “You never give up, do you, Harry?”

“He’s a creature of habit,” I said. The croissant muffled the words in my mouth and flakes dropped all over me so I jumped up and down to shake them off. “That’s what you always say. Like all of us.”

“Seen Marianne this morning?” Frank asked.

I nodded. “I expect she’s in her studio now.”

I shoved my feet in my shoes without pushing my heels in and scuffed after Frank and Harry. Slowly Harry headed to the meadow, as always, in that kind of, oh yeah, I nearly forgot, there’s a lovely meadow for me here kind of way. I hoped Frank still thought that too. That this was the place where they both fitted perfectly.

Frank pointed towards something lying in the grass. I’d left my other shoes in the meadow yesterday. Harry had chewed on them. Frank had made me lots of rules since he lived here. Marianne said artists don’t like rules. But I’d got used to Frank’s because he was never mean and bossy, and that helped me remember them, almost all the time.

“Oh,” I said, picking the shoes up, disappointed I’d done something stupid. The canvas was shredded, the laces unravelled. “I know, I know, I’m not supposed to leave anything in the meadow. Sorry, it was just this one time I forgot because Peter and I were hiding things in the grass and trying to find them with bare feet and our eyes closed. I won’t do it again.”

“Hope—”

“I don’t mind, honest. I’ve got these,” I lifted my foot up to show Frank the new ones and hooked the back with a finger to get my heel in. “The others were too small anyway.”

“What might happen to Harry if he ate something he shouldn’t?”

“Oh.” But Frank didn’t make me feel stupid, just kind of like I’d try harder next time. “Sorry. Sorry, Harry.”

Frank shoved his hands in his pockets and I followed his eyes to the snow on Canigou. I hadn’t finished what I was saying earlier.

“Do you think it works the other way around?” I said. “I mean, because of the environment, because Canigou is different today, can it change us?”

Frank had stayed put for three years now. Had he changed enough to stay for good?

I looked across and Frank didn’t say anything because we had this other kind of quiet world where we totally got each other. He taught me you didn’t always have to have an answer straight away.

“Where you off to today?” he said instead.

“I was going to the waterfall,” I said, cramming the last of the croissant into my mouth. “Peter and I were going to check on the swing to see if it needs fixing, ready for summer holidays. But actually I think I’ll stay here today. With you and Harry.”

“Peter’s last day, isn’t it?” Peter went to boarding school in England and was only home for the break.

“Yes, but—”

“Go on,” Frank said. “I’ll be here when you get back.”

I still didn’t go.

“I’ll find some wood.” He smiled.

I knew that meant we’d sit outside by the fire-pit this evening, talking in the honey-coloured light with the mountain looking over us. About all the things I couldn’t say to Marianne.

All I had to do was find a way to remind Frank of all the good things about being here, all the good things that made pairs of us, and then he wouldn’t even think about going anywhere else.

I nodded.

“See you by the fire later,” he said.

(#uf27b165c-17f4-558c-a97c-e76aa4aac4d5)

Before I met Peter, I’d only ever heard that he was the rich kid from the vineyards and didn’t play with anyone else in the village, which was enough information for me to think we’d never be friends. The day that Frank and Harry arrived three years ago, Peter turned up too. He sat on the meadow fence and watched Frank introducing me to Harry, and then all Peter did was come over and ask Frank if he could stroke Harry too.

Frank said what he’d already just said to me when I’d asked the exact same question. “You need to give Harry a bit of time to get used to you first.” I looked at Peter’s big brown eyes, and when Frank said, “He doesn’t know yet if you’re going to be kind to him,” I murmured along with Frank what I knew he was going to say next: “even though I do.”

I had one more day with Peter before I lost him to boarding school and would have to wait ages for him to be on holiday again. I ran across the meadow and Harry trotted alongside me until I climbed through the hole in the fence, into the vineyard, and raced on to Peter’s grandparents’ house, turning back to see Harry with his chin up on the top rung, his ears pointing high, watching me go.

“See you later, Harry!”

That donkey would always think he was coming with you.

Peter was dressed smart, as always. Even if we were going crawling through vineyards or driving Monsieur Vilaro’s rusty old tractor he looked kind of pressed and tidy and new. I liked my clothes, they made me feel comfortably like me, but I always got the feeling when I was next to Peter that actually my clothes were scruffy, not casual.

Peter was packing a towel into a bag.

“Are you going swimming? We never swim until July. The water’s too cold,” I said. “And anyway I haven’t brought a towel.”

“I’m going to swim; you can watch. If you change your mind then you can share my towel.”

“I thought we were going to make the swing ready for when you come back?”

“We are,” he said, winking. “Ciao, Nanu,” (which means Bye, Nanny) he called back as I followed him outside. Peter’s grandparents were Italian and although they’d lived here in France for over fifty years, they still didn’t speak much French or English, unlike Peter.

Outside, Peter said, all kind of secretive, “Today’s the day.”

“The day for what?”

“Jumping off the waterfall.”

“You say that every year.”

“I mean it this time.”

“What, from the top? You’ve always said it’s too high.”

“But I’m taller than I was before.”

I looked at the top of his head. With my hand, I measured his height against me, pressing his thick wavy hair down in case that was what was making him look taller, but he’d had his hair cut short ready for school, so it wasn’t that.

“For the first time ever, you are actually just a teeny, weeny bit taller than me,” I said, which made him grin. “But I’m not doing it.”

As we walked we discussed the good and bad things about jumping off waterfalls, asking each other if we’d heard of Angel Falls and Victoria Falls, Peter agreeing in the end that he would swim to the bottom first to check if there were any rocks under the water.

There was a shortcut across the Vilaros’ field, although we weren’t supposed to use it, and when we got near the gate the Vilaros’ guard dog, Bruno, blocked our way. Bruno usually just paced around the field, guarding against… well, I had no idea what, but this time he barked and barked at us in that way that made you not want to go any further.

Bruno’s chops dripped drool with the effort of the big noise he was making and Peter turned and walked back down the lane (well, kind of ran actually), probably expecting me to be right behind him as usual. Bruno was a big dog, not a house dog, with battle-tatty ears and grey chops, and I’d never taken much notice of him before, except when I had to avoid him on the way to school, but there was something about him that day that I couldn’t ignore.

“All right, Bruno, we’re not going across the field,” I said.

He kept barking, to tell me he was on patrol and wouldn’t be letting us past.

“Hope, come on! We can go through the vineyards instead,” Peter called.

All the dogs in the village were crazy with something that day and although Bruno was usually barky and grumpy, he seemed more upset than usual.

“Peter, I think something’s wrong.”

“Come away. Bruno doesn’t look very happy about us being here.”

“He’s never bitten us before.”

“That doesn’t mean he won’t today.”

“Peter, wait. I can’t just leave him on his own like this.”

In my pocket were some sherbet lemons. I thought if I gave Bruno something sweet it might make him stop barking and howling like that. I threw one at him and he snatched it up and spat it out again, probably because when you think about it lemons aren’t that sweet at all. He kept barking, looking at Peter and me, then staring up at the mountain.

“Look, Peter. Bruno isn’t even barking at us. He’s barking at the snow.”

Peter peeked out from behind the hedge at the bottom of the lane, his eyes wide when he realised I wasn’t with him, madly waving me to come.

“Bruno?” I said. “Are you talking about the mountain?”

Bruno watched Peter creeping back up the lane on tiptoes, all hunched up and clinging to the hedge, whispering, “Hope! Please come!”

“Peter, you’re being silly,” I said, “Bruno isn’t going to hurt us. I think he might even be trying to talk to Canigou, and he has to bark big and loud like that so it can hear.”

Peter rolled his eyes at me, which he does a lot, and said, “Now who’s being silly? Let’s go!”

By now Peter had crept back to where I was. He grabbed my hand and then I was running with him down the lane in that way, you know, when you feel like you’re not going to stop and it makes you excited and scared at the same time, and you scream and laugh together, and it felt good so I didn’t look back at that big old barky dog.

Peter and I climbed over the vineyard fence and through the hole in the hedge, a hole we’d made for avoiding Bruno before. We ran up the long path of stony earth between the vines, turned right to go through the next vineyard, and then across the track behind the Vilaros’ field. Bruno had raced through the field up to the wall and was still barking, his paws up on the wall, and then suddenly he stopped. Everything went silent. After all that noise, it made me look up instead of where my feet had to go.

“Peter!” I pointed, because I didn’t know how to say what I was seeing, although what I felt like saying was: The mountain answered Bruno.

It seemed to me like Canigou was a giant that had been asleep for a long time, breathing slowly, very slowly. And then maybe what happened was that the cold of the new snow was too heavy, too wintry and unexpected, and the mountain had to shift a bit to get comfortable again. And that made the avalanche happen.

A huge chunk of snow was falling down the mountainside, making a big white billowy mist, as if it was turning back into a cloud of snowflakes again. Even from where we were, the rumble of the fall and the crack of snapped trees echoed across to us as the avalanche slid down.

Peter moved in front of me. He knew as well as I did that the snow was too far away and would never reach us – that we were safe – but looking out for me was the kind of thing that Peter did.

We stood there for a long time watching the snow roll and tumble, until at last everything stopped and was quiet again. Even the insects had stopped buzzing and the leaves had stopped shuffling. It was now really, really quiet.

“The mountain shrugged,” I whispered, because that was what it seemed like to me.

Peter rolled his eyes again. “The world according to Hope Malone,” he said, like he usually did.

People appeared; Monsieur Vilaro on his tractor and some people who worked in the vineyards, running up the slopes with Peter’s grandfather, Nonno, all heading towards the edge of the spilt snow.

Nonno saw us and came jogging over, his bandy legs making him lurch side to side. He wiped the sweat from his forehead, spoke to Peter in Italian, before swaying back to the men all gathering together.

“Nonno said we should go home,” Peter translated. “To stay out of the way, just in case another avalanche happens.”

We didn’t go, not straight away, even though Peter was pestering me to leave, to do as we were told.

“Can you feel it, Peter?” I whispered.

“The snow?”

“I don’t know. Something like that. I can smell it too.”

I held out my arms to see if the air felt different on my skin.

“It seems the same to me,” Peter said.

We went back the way we came, through the vineyards towards my house, and I saw our footprints from where we’d walked earlier, where the red earth was softest, exactly as we’d left them.

Everything was about to change though, and, like the avalanche, there was nothing I could do to stop it.

(#uf27b165c-17f4-558c-a97c-e76aa4aac4d5)

“Frank! Where are you?” I called, as Peter and I ran up the drive.

Harry came first, trotting up from the meadow to see what was going on. The meadow had fences on three sides, except the top side next to the gravel drive, although Harry usually acted as if there was one there and didn’t stray out.

There were old rotting planks of wood stacked outside the guesthouse, and the guesthouse door was open. Frank came out.

“There was an avalanche on Canigou!” I said, with the little breath I had left.

“You OK?” said Frank, pulling me close.

I nodded against his chest.

Frank held me away and looked into my face. “How far did the snow come down?”

“As far as the casot,” Peter said. “You know, the old shepherd’s hut?”

“Has anybody else gone up there yet?”

“Nonno’s there and a few others.”

“I’ll take the top road in the jeep, see if there’s anything I can do. Hope, tell your mother where I’m going.”

Frank, as he always was. Frank to the rescue.

He ran to the jeep and Harry followed him.

“Not this time,” Frank called to Harry. “Keep hold of him, Hope!”

Harry tried to go after him. Peter and I held on as best we could, our feet skidding in the dust as Harry dragged us along for a bit. Even though he was little, with short thin legs, he was really, really strong. Harry couldn’t help himself, he always wanted to go with Frank if Frank was going anywhere.

As the jeep sped off, Harry watched the dust spitting up behind, his ears leaning right forward as if they were still following the sound of Frank leaving.

“Come on, Harry,” I said. “Back to the meadow.”

It was easy to say that to him, but Frank was the only one who could get Harry to do what he wanted.

I got carrots from the kitchen to try to lead him down there, but he stood there for ages, not moving, no matter what Peter and I said.

Sometimes I wasn’t sure how much Harry understood, although he seemed to completely understand Frank. Even though Frank didn’t say much to him, there was a whole world of things that they said to each other without words. Other times, I thought Harry was just thinking like a donkey has to think: about all the fresh grass at his feet and how much he could eat before going in his shed for the night.

Harry wouldn’t look me in the eye, but then again he never did. Not even with Frank. In fact, Harry always looked kind of sad, and that was probably because of the way his head drooped as if there was something heavy on his mind.

The words to describe Frank and Harry are those that anybody would understand: best mates. The best way to describe what Frank was to me is like this:

One day a man (I forget who) came over to our house to see Frank about getting some carpentry work done. I was outside and so was Frank, who was painting the shutters, and the man said hello to me first, and then he saw Frank climbing down from the ladder and said, “Can I speak to your dad?”

And I said, “He’s not my dad, he’s my…” and couldn’t finish what I was saying, even though that wasn’t what the man thought was important right then. My mouth was still open, ready to say a word that fitted exactly right after ‘my’, but Frank was already striding over holding out his big brown Australian hand, which had paint on it, and he wiped it on his jeans first and said, “I’m Frank, what can I do for ya, mate?”

Marianne told me my father was an art dealer. I’d never met him so I didn’t miss him because I didn’t know him or what there was to miss. He didn’t fit with us and I suppose we didn’t fit with him either, so I was OK with that. But me and Frank, we’d never filled in the blank about who we were to each other.

It took ages for Peter and me to get Harry to go to the meadow. In the end, I think he made up his own mind to go.

Peter and I wandered back to the house talking about what we thought everyone might be doing up at the avalanche and I noticed that Frank had left his door open. I wasn’t ever supposed to go in without knocking and never had, but I was sure he hadn’t meant to leave it open.

As I closed the door, through the gap I saw a pile of clothes on Frank’s bed.

For a minute, something like that makes your mind do all sorts of things. Like adding things up. Passport, half-packed bag and… what else? Just a kind of uncomfortable feeling.

I ran up to the roof.

“Where are you going?” Peter said, running up after me.

“To see.”

Because of the plane trees, we couldn’t see the casot or where the snow had fallen from there. Most of the land belonged to the Massimos and Peter was quiet until he said, “Where the snow fell, that was where the new vineyard had been planted.”

I wanted to feel something about what he said, but I couldn’t. I wanted to see something else other than Frank’s travelling bag and the passport in his pocket.

(#uf27b165c-17f4-558c-a97c-e76aa4aac4d5)

When Frank arrived home later, Harry headed straight back up from the meadow and went over to the jeep, walked all the way around it and then followed Frank.

I hung back.

“Was anyone hurt?” Peter asked, running up to him.

“The casot helped stop the avalanche,” Frank said. “The snow’s wedged up behind it. It’s smashed up a bit but it looks like nobody was up there.”

“It doesn’t matter about the casot; nobody’s used it for about fifty years,” said Peter.

“The new vineyard… it’s under the snow too,” said Frank softly.

Peter’s shoulders dropped. His family wanted to make more wine and more money, give more people jobs. The soil and the sun and the vines and the Massimos all fitted together perfectly up here too.

“New things will grow,” Frank said. “They always do.”

“Was Nonno OK?” Peter said. “He gets tired easily.”

Frank smiled at Peter and touched his shoulder. “I gave him a lift home.”

“I’d better go back. I want to see him.”

“Peter! Will I see you before you go?” I said.

“Ciao, Hope! See you in the summer,” Peter called as he ran.

“Family comes first, hey?” Frank said.

I was still standing on the porch not knowing what to say.

“Frank?” I caught his sleeve and asked him. “Are you going somewhere?”

Moments passed while he seemed to measure out the right amount of words to say, while I hooked my fingers together around his arm.

At last, he said, “Nonno has asked me to help with digging out some of the vines and posts from the snow, see what we can salvage of the new vineyard. Might take weeks, or more.”

“You’re not going anywhere else?”

“Like I said, I’m needed here.”

Had Frank been about to leave? If it hadn’t been for the avalanche… I looked back at Canigou. I knew I had always been right about my giant friend: that it stood by me, no matter what.

“Come and help me light the fire,” Frank said. “We still got some talking to do.”

My mother turned out the lights in her studio upstairs, which meant that Frank, Harry and I were the brightest things on the hillside, made amber by our fire.

Frank went inside and brought out some papers to throw on the fire, and we collected up the old rotting bits of wood that he’d been sorting out earlier to burn. I leaned on him, hooked one leg over his so he knew I wanted to sit in his lap.

“You’re really comfortable to sit on, Frank.”

“You’re getting kinda big,” he said after a while.

“I’m not heavy though, am I?”

He laughed. “Big on the inside.”

I sat on a shorter log next to him.

“I’m cold now,” I said.

He gave me his sheepskin jacket. Sheep were the warmest creatures, he’d once said, and he thought it was mad that millions of them lived in the sweltering heat in Australia, which was where Frank was born. Wrapped in his jacket was kind of like being Frank, or at least part of him, smelling of fire smoke and the outside and long journeys.

I leaned my head against his side. Harry came over and blinked from the heat of the fire.

Frank threw old papers into the flames. The little burning pieces shot into the sky and made us our own kind of fluttering stars. Flakes of the burnt papers fell towards me as they died in the sky. I caught one and it made a soft grey mark on my palm.

“We gonna talk?” Frank nudged me and I didn’t answer for a while, probably like him, weighing up what I did and didn’t want to say.

“I’ve been thinking,” he said. It wasn’t like him to go first. It was usually me spilling over with questions. “What you said earlier about cherries.”

“I’m right, aren’t I?” I smiled into the fire.

“I get it.”

“I know. I never knew anyone before like you or Harry.”

We were both quiet again after that.

Everything turned to shadows when the sun fell behind Canigou, making the sky bright blue around our mountain’s shoulders. I had a different feeling, of being held up like a piece of washing on a line by a flimsy wooden peg.

“Spill,” Frank whispered.

Perhaps it had always been hard for him too. I wanted Frank to understand what I didn’t know how to say. That even if my mother and he didn’t want to be together, that somehow we’d still be each half of a pair, even if there wasn’t a word for us.

The only reason we’d all come together in the first place was because of Harry. Harry’s life hadn’t all been happy, but if it wasn’t for that donkey, none of us would ever have met.

I nudged Frank and he squinted one eye in that here-we-go-again kind of way but with an added ton of patience, because he knew what I wanted to hear.

“You want me to tell you again how I found Harry?” he said.

“From the beginning.”

(#ulink_8d71ee90-1f04-5631-8278-c9dd02f8f949)

Frank hadn’t exactly told me the story of Harry, not like someone normally tells you a story, by starting at the beginning, going on to the middle and then ending at the end. You had to prise bits of it out of him, ask questions, even the same ones again and again, and then sometimes he’d let a bit more spill. But the end of the story was always the same. They ended up here.

Sometimes Frank talked about ‘the grey donkey’ rather than Harry. I thought maybe he was protecting Harry by not calling him by his name when he spoke about where he came from. Or maybe it was so Harry wouldn’t hear. Like I said, you never can tell how much a donkey understands.

Actually, I hated the story, because of what had happened to Harry, but I loved it too. Because of Frank.

“Fire away,” he said, like always, and we both smiled because the bonfire and the talk had always gone together.

“How did you find Harry?” I began.

Frank took a big breath, like he was preparing himself deep down inside. He picked two sappy grasses, held one out to me, getting ready to go travelling in his memory and take me with him.

“Paths crossed, I reckon.”

“Where was it you were going?”

“Travelling, that’s all.”

“But, like, where were you exactly?”

“India, Mumbai, near a building site.”

“And what were you doing at the building site?”

“Just looking, watching things change.”

“What made you stop for Harry?”

He shook his head and twitched his lip as he crushed the grass stem between his teeth.

“There are some things that a man finds hard to pass by.”

I loved the way he talked. Bold and sure. Each time the answers familiar, but that day, strangely unfamiliar too. Maybe that was because of me hearing them differently, because I had grown since the last time he’d told me the story. Or maybe it was because something cold had settled in my stomach, like a sprinkling of snow.

“How big was the pile of bricks Harry was carrying?” I asked.

“Bigger than himself.”

“He was a good donkey though,” I said, knowing the story so well.

Frank nodded.

“So why did his owner treat him like he did?”

Again he waited a moment, leaving a space, like that silence was the place for me to work things out, to be ready to see the things he’d seen.

Frank threw the last of his papers on the fire. New sparks rose.

“When the donkey fell, the man couldn’t see that he’d have got up if he could.”

“What did you do, Frank?”

He poked the ashes with a stick.

“Pulled him back on his feet.”

I didn’t ask any more about this part of the story, eager to get past the struggle that I couldn’t bear to hear. Frank had never given any details, as if he was saving poor Harry from being shamed by what happened. And I kind of understood, if you can call it understanding by putting your own thoughts in a donkey’s head. Harry was strong and willing and he would have got up if he could, but Frank had to help him.

“You wanted to carry some of the bricks for Harry,” I reminded Frank.

He studied the crushed stem he’d been chewing. It took him a long time to answer and I wondered if there was another bit missing, a bit that Frank didn’t tell me.

“I made it worse. Poor grey donkey,” Frank said. I never understood this. How could anything be worse than poor Harry almost buried under his load? But Frank said no more. I wondered if he did it on purpose, stopping right at that point to give his story just about as much weight as Harry’s burden of bricks, to let the fact of the story sit inside me for a while so I could feel how heavy his heart had been when he’d seen the grey donkey buckling and having no choice but to try to get up and carry on.

“But you saved Harry! You bought him and took him away and he’s never had to work hard like that again.”

Frank rested his cheeks on his fists. He’d gone quiet. I knew the story so well I filled in the rest for him. The good bit.

“You rescued Harry. Together you travelled across countries that I’ve never even heard of, your tyres popping all the time while you drove up those stony mountain roads, following your friends from Germany who were on their motorbikes and who had maps of how to get to Europe. Then they helped you get visas and papers, to have all the checks that you and Harry had to have.”

I followed Frank’s eyes to the bonfire, to the papers now burning at our feet.

“And you avoided all the places where people would ask you too many questions about Harry, and all the time he was safe in the trailer behind your jeep with a pile of straw and a bunch of carrots.”

I could feel the freedom they must have had, travelling along like that together.

Frank looked over at me and I couldn’t help that the smoke from the fire was getting in my eyes.

“Then he had to go into quarantine. You hated that bit, being without Harry. I would too.”

“Listen,” Frank said. “Like I said, I’ve been thinking—” but I didn’t want to hear. I didn’t want any of the words to be things I didn’t want him to say. I hadn’t meant to remind him that he loved travelling but I couldn’t hold things in any longer. If Frank left, and Harry with him, I didn’t know what I’d do.

“So have I,” I said, wedged up against him. “And right now it feels like only a minute ago that you and Harry arrived. And I feel the same, exactly the same as I did when I first met you and Harry.”

He rested his head on mine. I kept going.

“Remember when you came? All the dust your jeep kicked up, making big sandy dust flowers blooming along the lane all at once. Like all of a sudden everything was ready for you. Or we were. And I know you didn’t say yes at first…” I pulled Harry closer so Frank and Harry made a sandwich around me. “I remember you stood there for the longest time at the edge of the meadow and Marianne said there was no reason a donkey couldn’t live here because nobody used it. And you talked to Harry and I wish I knew what you’d said to him. Was it you or Harry who decided to stay?”

Frank laughed softly.

“Harry.”

“Harry?! See, he knew this place was right for you. Freshest greenest meadow he’d ever seen in his life, that’s what you always say. And I said I’ll brush him for you, he looks kind of grey, and you said…”

“He’s grey underneath that dust too.”

We smiled at Harry, his head and eyes drooping with sleep, standing quietly beside me. We touched him gently and I knew it was impossible for either of us ever to be without him. Harry chose the meadow, and that put me and Frank together too.

“You tell the story of Harry better than I ever did,” Frank said.

“He’s like the reason for all of us being together, Frank.”

I hoped that made sense to him and I think it did because he smiled in that way that made me feel even the whole world had nothing like we had.

He spoke to Harry, like I was supposed to hear too.

“What are we gonna do about you, Harry? You’ve still got some bad old habits, mate, and it’s just not good for you. I think we’ve gotten too used to each other and I’m not sure I can help you break them any more.”

Sometimes you want to show someone that there’s a good reason why you’re together too.

“I could help,” I said. “I mean, like you said, I am growing up and I love Harry. I could help him.”

Frank leaned over to Harry and patted his neck, slowly running his hand down Harry’s nose, having the kind of conversation that only they could have without saying any words. Then Frank said to him, “What do you reckon, Harry? Do you trust Hope? Me too.”

“Really? I’ll train Harry?”

“That’s what I’ve been thinking. Nobody knows Harry like I do. It’s about time I let you in on that.”

“What, like, me look after him? Me and Harry?” Beautiful, sweet, safe Harry.

“How about we start now.”

(#ulink_57fd3d5b-57a5-5304-a535-69a3a0529520)

“See if you can put Harry in for the night,” Frank said.

“What do I do?”

“Wait here a second.” He strode ahead over to the bench outside the guesthouse and sat down. I guessed he was getting out of the way so that Harry and I could do this together by ourselves.

He called, “Tap his shoulder twice, left shoulder, and he’ll follow.”

I’d seen Frank do it a thousand times, but it’s not the same when you do it yourself and you haven’t realised it has to be his left shoulder and your fingers are nervous. Harry curved his neck around and looked at my hand. Like we didn’t speak the same language, not yet anyway.

“Come on, Harry,” I said, and started to walk. He didn’t follow.

I went back and did it again and Harry looked at my hand again, and I told him again, “Harry, come on, time to go inside.”

Harry looked over at Frank, one ear up, one ear down. He stayed where he was.

“Does he only understand Indian?” I said, which I realised was stupid as I’d never heard Frank use any other language.

Frank laughed. “It’s not the words or your voice he’s listening to. You have to feel that you mean it, so he feels it too. Feel sure. Then he’ll be part of you.”

Frank was about to get up and come back over. Of course that was what I wanted. Me and Harry, Me and Frank.

“Yes! I can do it. Give me a minute.”

Frank sat back down.

“And I was only joking,” I called over. “About talking Indian, I mean.”

“Take your time. He’ll be ready when you are.” Frank leaned back, rested one ankle on the other knee, his arm stretched across the back of the bench.

I stood beside Harry, tidied his fringe. I didn’t want to disappoint anybody, including myself. I knew there was something between Harry and me that I had to find – what Frank and Harry had, what Peter and I had. When you just kind of fall in with each other’s footsteps.

I looked over at Frank.

If I looked after Harry, would I be completely in their world? Would that make it impossible for me and Frank and Harry to ever be apart? It was all I wanted. I’d never wanted anything so much, or tried so hard.

I thought of me and Harry. Of us being like yoghurt and honey too. I tapped Harry on his left shoulder twice. This time, he followed.

I couldn’t stop smiling at the little grey donkey, who was with me in a way he’d never been before. It felt huge and new and exciting.

When Harry got closer to his shed, he went over to see Frank. Maybe Harry was just checking they were still best mates, or maybe he wanted to tell Frank in his nuzzly donkey kind of way that he was OK with the choice he’d made for me to look after him too.

Frank sat forward, wrists dangling over his knees.

“Good boy, Harry,” he said.

Harry leaned his head over Frank’s shoulder. They said something else to each other again, but not in words or a language I understood, yet.

“Has he got clean water?” Frank said.

I checked inside the shed and ran back to tell him, “I filled the bucket up, right to the top. And changed the bedding.”

Frank patted Harry, just like he always did. I loved that about Frank, how he changed things without anyone being left out.

“G’night, Harry, mate,” he said. Magic words.

Harry turned away and I took him into the shed, fresh with straw and an apple I’d left for him to chomp on.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/sarah-lean/harry-and-hope/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Sarah Lean

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Природа и животные

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Some friendships are meant to be… A story about family, friendship and belonging, from bestselling author, Sarah Lean.Hope lives with her artist mum in the Pyrenees. It’s always been just the two of them… until Frank – a free-spirited traveller – arrives with his donkey, Harry.Hope and Frank form a close bond, so it’s hard for both of them when Frank decides it’s time to move on. Hope questions what she is to Frank. He’s not her dad, but he was more than just her mum’s boyfriend. Except, there’s no name for that kind of pair…Hope promises to look after Harry and, slowly, another special pair is made – one that makes Hope realise that some friendships become part of you and, even when someone is far away, they are always near to your heart.