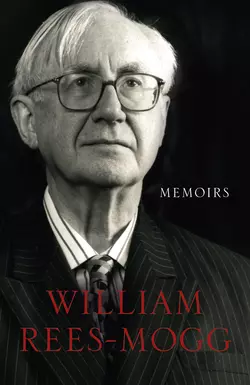

Memoirs

William Rees-Mogg

William Rees-Mogg is one of the pivotal figures of post-war Britain. In this brilliantly entertaining memoir he recounts the story of a colourful life, and reflects on the key figures and events of his time.As editor of The Times (his glory years), journalist, commentator, Chairman of the Arts Council, and, later, Chairman of the Broadcasting Standards Council (when he was accused of censorship), William Rees-Mogg has spent his life at the centre of events in politics and journalism.Often controversial and never dull, he has always had the courage to hold strong, fiercely defended opinions which go to the heart of the problems of the day. From his famous defence of Mick Jagger on a charge of possessing cannabis when he attacked the ‘primitive’ impulse to ‘break a butterfly on a wheel’, to his recent criticism of the morality behind the war in Kosovo and defence of monetarism, his writing has demanded attention, to the point of becoming newsworthy in itself.He knew and knows most of the anybodies who were anybody, from royalty to prime ministers, presidents, business magnates and religious leaders, and uses his unique insider perspective to great effect, with perceptive, sometimes provocative, recollections of people such as Rab Butler, Margaret Thatcher, Anthony Eden, Shirley Williams, Roy Jenkins, Robin Day, Rupert Murdoch and many more.From an early age his life was filled with incident – among the many anecdotes are the stories of Noel Coward’s goldfish, his failure to inherit £30,000, his near-shooting at Trinity College, Oxford, an eventful stay at Chequers with Harold Wilson, conspiring with Shirley Williams against the Communists, his doomed attempts to enter politics and dinner with Ronald Reagan and Harold Macmillan.

WILLIAM REES-MOGG

Memoirs

Contents

Cover (#uf2921864-5069-5d8c-83cb-a80aed57a4c8)

Title Page (#u05940f47-0f40-580a-89c1-1ed446e58091)

List of Illustrations

Foreword

Chapter One - The Young Actress

Chapter Two - The Young Officer

Chapter Three - A House Built on a Hill

Chapter Four - A Peak in Darien

Chapter Five - But we’ll do more, Sempronius

Chapter Six - Everyone Wants to Be Attorney General

Chapter Seven - ‘A University Extension Course’

Chapter Eight - Thank you very much for … the Sunday Times

Chapter Nine - Sadat’s Viennese Ideal

Chapter Ten - Rivers of Blood

Chapter Eleven - ‘The future of Europe is not a matter of the price of butter’

Chapter Twelve - Palladio on Mendip

Chapter Thirteen - The Times ’ Lost Year

Chapter Fourteen - My Life as a Quangocrat

Chapter Fifteen - The Best of Business

Chapter Sixteen - My Road to Bibliomania

Chapter Seventeen - R. v Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, ex parte Rees-Mogg

Chapter Eighteen - ‘ An Humbler Heaven ’

Index

Acknowledgements

Picture Section

Copyright

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

List of Illustrations

William, c. 1936 (Private Collection)

Cholwell, 1936 (Private Collection)

Fletcher, Beatrice, Aunty Molly, William and Andy, 1936 (Private Collection)

William, c. 1946 (Private Collection)

William as President of the Oxford Union, 1951 (Private Collection)

William reading the Evening Standard (Photograph by Otto Karminski © Times Newspapers)

The Rees-Mogg family at Ston Easton (Photograph by Anne Rees-Mogg)

Iverach McDonald being presented with a salver by William, 1973 (© Times Newspapers)

Roy Jenkins and William, 1978 (Private Collection)

Harold Wilson, William and Marcia Williams, 1963 (Photograph by Kelvin Brodie © Times Newspapers)

William addressing editorial staff, 1980 (Photograph by Bill Warhurst © Times Newspapers)

Press conference in London to announce the sale of the Times Newspapers Ltd to Rupert Murdoch (© Times Newspapers)

William with Margaret Thatcher, 1999 (Private Collection)

Pope John Paul II and William (Private Collection)

William with Alfonoso de Zulueta and Shirley Williams, 1966 (Photograph by Stanley Devon)

William photographed in 1982 (Photograph by Bill Warhurst © Times Newspapers)

William’s eightieth birthday (Private Collection)

Portrait of Alexander Pope (Photograph by Maud Craigie)

The Mogg family, painted by Richard Phelps c. 1731 (Photograph by Magnus Dennis)

Portrait of John Locke (Photograph by Maud Craigie)

Self portrait by Joshua Reynolds (Photograph by Maud Craigie)

William Pitt, Earl of Chatham, by Richard Brompton, 1773 (Photograph by Maud Craigie)

Foreword

In January 1977, my senior editorial colleagues gave a dinner at the Garrick Club to celebrate my tenth anniversary as Editor of The Times. It was a very pleasant evening for me, among people whom I regarded as both colleagues and friends. Charles Douglas-Home, himself due to become a distinguished Editor, had chosen a case of Château Lynch Bages as a present; I have only recently consumed the last bottle. I cannot recall the whole guest list. Louis Heren was in the chair, as Deputy Editor. Naturally we talked about The Times, with a good deal of confidence, despite the recurring problems with the print unions. We had no idea of the militant trade union crisis that was to come. Our proprietor, Roy Thomson, had died a couple of years before, but his son, Ken, had taken his place in an atmosphere of goodwill on both sides. Ken followed Roy’s principle of avoiding interference with the editorial side of the paper.

I remember, at the end of the evening, walking down the front steps of the club; Peter Jay was next to me. When we were about halfway down the steps, a thought passed through my mind. This surely was going to be as good as it would get, at least in personal or career terms. Would it not have been a better conclusion to my editorship if I had taken my colleagues by surprise and announced my intention to resign in my brief speech of thanks at the dinner?

I put the idea out of my mind, even if it was ever wholly present. I could hardly wheel round on the steps of the club and ask everyone to go back to the table, so that I could make a little announcement. In any case, I knew Ken Thomson better than any alternative Editor; I could hardly leave the paper until he was completely settled in. The moment passed before it had even fully formed. Nevertheless, the intention had entered my mind, and if I had had time to think it through I would have seen that there were strong reasons for following the advice of my subconscious mind. The next four years, with the closure and then the sale of The Times, was a difficult period. A contrast to the mood of the dinner I was just leaving.

If I had resigned at that dinner I would have been spared the worst crisis that The Times faced in the twentieth century, the one-year stoppage, and I would have had another four years to develop the next stage of my life.

Ex-Editors do find it difficult to establish a second half to their careers. I remember my first Editor, Gordon Newton, of the Financial Times, saying of his own retirement, ‘there is nothing so dead as a dead lion’. Some Editors have had successful careers in business. There is a phrase for the strategy of moving from a single big job with major executive responsibility, to the non-executive jobs which are more likely to be available. It is said that these personages have gone ‘multiple’. At any rate I went multiple, and have had geological layers of different forms of employment in the period since I made a final retirement from editing The Times in 1982. The only trouble I have found is that the jobs one is offered after the age of seventy tend themselves to be time-limited.

In fact I have found plenty of interesting things to do since 1982, and am still writing columns for The Times and the Mail on Sunday. I am struck by the fact that most of the work I have done in journalism, in business, in helping charities, has been cyclical in character. World politics faced the threat of the Cold War and now faces the growth of terrorism. When I started in journalism in 1951 there was a liberal Conservative Government in power. Sixty years later there is a Liberal/Conservative coalition. I myself have enjoyed writing about the swings and circulating on the roundabout.

Chapter One

The Young Actress

I was born in the Pembroke Nursing Home, Bristol, England, of an American mother and an English father, on 14 July 1928. It was a hot night and a difficult labour. My mother had been determined that I should not be born on Friday the 13th, because she thought it would be unlucky. In consequence I was born at about 4 a.m. on Bastille Day, France’s national holiday, and knew as a child that my birthday was a special day of celebration. I was a large baby, weighing some nine pounds, three ounces. At some point, during or after the delivery, my mother’s heart stopped beating, and had to be restarted with a new drug which had recently been used on King George V. Whether my life was at risk during the delivery I do not know; my mother’s certainly was.

As a young child I had a recurrent dream. I am travelling up a shaft, which has ribs. When I reach the top of the shaft, there is a light, and there are large people, giants. They assist me to emerge from the shaft. I awake, feeling that I have passed through a crisis. I am by no means the only person to record such a dream, which is sometimes explained as recalling the birth trauma, and sometimes as a near-death experience.

My mother, Beatrice Warren, born in Mamaroneck, New York, in 1892, was an Irish-American Roman Catholic and a successful Shakespearian actress. All four of her grandparents had emigrated to the United States from Ireland in the 1850s; both her grandfathers then fought for the North in the Civil War. They came from the Irish Catholic middle class, ‘lace-curtain’ rather than ‘bog-trotting’ Irish. They had experienced the famine but survived it. My mother was the eldest child of her family, and for seven years had been an only child.

I have a very vivid picture of her childhood. In the 1890s she had the regular morning treat of being driven to Mamaroneck station with her father, where he caught the commuter train into Grand Central Station. They were driven in the carriage by Arthur Cuffey, the black coachman and handyman. At that time they lived on Union Avenue, though her father later built Shoreacres, a beautiful early twentieth-century house which looks out over Long Island Sound. Her evening treat was to take the same drive to meet the evening train. They had a good quality carriage horse, called Miss Gedney, whom her father had bought from a man in White Plains.

My mother’s father, Daniel Warren, started his working life as a clerk at Harrison Station, which, as every Westchester commuter knows, is the stop between Mamaroneck and Rye. He had been known as a bright lad. His father, old Mr Warren, had prospered as an immigrant and had risen to be a line manager of the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad. He got his sixteen-year-old son the job on the railroad.

One morning in 1881, Daniel was standing on the platform where the train to New York was about to arrive. A regular business commuter, Mr Eddy of Coombs, Crosby and Eddy, was standing beside him. Mr Eddy had a fainting fit, and started to totter. As he fell forward, Daniel grabbed him; the locomotive brushed Daniel’s arm as it passed. Mr Eddy thanked Daniel for saving his life, gave him his card and asked him to call on him at his office in Wall Street. When he did so, Daniel was offered a job, rejected a flattering counter-offer by the railroad, and worked for Coombs, Crosby and Eddy, later merged into the American Trading Company, until he retired in the 1920s. He ended his career as the vice-president, which then meant that he was the executive running the business. The American Trading Company, with a strong Japanese connection and branches in many countries, became a powerful international trading house. J. P. Morgan, whom Daniel greatly admired, invited him to join his new club, the Metropolitan. Daniel replied: ‘Mr Morgan, I am flattered by your invitation. I greatly appreciate doing business with you. But I am an Irish Catholic. I do not belong to the same society as you do.’ Nevertheless, the American Trading Company was chosen to advise the Morgan Bank when, in the early 1900s, Morgans wanted to expand into Japanese finance.

In 1888, he made a trip through northern Mexico with eight large trunks of manufacturing samples. At the end of the Mexican National Railroad at Saltillo, he had to hire mules to carry these trunks over the mountains, which were overrun with bandits and outlaws. He remembered hiding behind a wall with a Mexican friend; some shooting was going on. His friend asked him what passport he carried; he replied ‘American’. The Mexican advised him, ‘Do not say “Americano”, say “Ingles”. They shoot Yankees; they do not dare shoot the “Ingles”.’ Such, in the high Victorian period, was the reputation of the British Empire, or perhaps just the Mexican dislike of Yankees. Daniel Warren, though his Irish ancestors had been nationalists, was an Anglophile.

He used to discuss the day-to-day problems of his business with my mother. She particularly remembered the panic of 1907. Wall Street was only saved by the rapid action of J. P. Morgan and a syndicate he formed. Her father acted swiftly and managed to save the American Trading Company, but many other firms went under. The family took their usual summer holiday in the Adirondacks, in upper New York State, and Daniel walked with Beatrice, then fifteen, and talked himself through the stress of the panic.

My mother had been enormously influenced by her relationship with her father whom she very much admired and whom she very well understood; she thereby created for me another role model. Indeed, although I never met him – he died in 1931 and he did not come to England in my lifetime – in some respects I was more influenced by Daniel Warren than by my father. In particular my interest in business and politics comes from my American side.

From a very early age, Beatrice knew that she wanted to be an actress. She could remember, as a child of seven, joining the recitations, which formed part of evening entertainment in the age before radio or television existed. Her party piece was a sentimental poem which ended with the lines:

Thanks to the sunshine, Thanks to the rain, Little white lily is happy again.

While she was at college, Beatrice told her father she wanted to go on the stage. A hundred years ago that was an unusual ambition for a well-brought-up American girl from a family of rising prosperity. Daniel replied that he would support her going on the stage, so long as she earned her own living for a year in some other way. She accepted that, and always regarded it as a sensible condition for him to have set. She taught elocution at Wadleigh High School for a year, commuting from Mamaroneck and getting off at the 116th Street Station. She could remember teaching girls who pronounced ‘th’ as ‘d’ – ‘dis and dat and dese and dose and dem’.

In 1914, Beatrice went on the stage. She was given an introduction, by Granville Barker, to Margaret Anglin, who was casting for a season of Greek plays, translated by Gilbert Murray, in the Greek Theatre at Berkeley, California. Beatrice became a member of the chorus. Alfred Lunt was also a trainee, carrying a spear among the guards. He and his wife, Lynn Fontanne, were to become the leading couple of the American theatre before the Second World War. Beatrice remained with Miss Anglin’s company for a couple of years. In 1916 she was playing the second lead in the Chicago opening of Somerset Maugham’s Caroline, later retitled as Home and Beauty. The author, a friendly but rather shy figure, was sitting in the stalls at the dress rehearsal.

One member of the New York artistic set was Putzi Hanfstaengl, an ardent young German nationalist. He was a son of the family of Munich art dealers, and had been sent to New York to set up a local branch of the firm. They already had a branch in Pall Mall, in London. Putzi gave Beatrice a couple of the firm’s celebrated reproductions, Dürer’s rabbit and Holbein’s drawing of Sir Thomas More, which is now hanging on our drawing-room wall. He argued heatedly in favour of Germany’s historic role as the dominant power in Europe. This would have been in 1915. Beatrice did not like Putzi, though she found his intellectual range interesting. During the Second World War she remembered these conversations, and believed that German imperialism was deeply rooted, that there was a continuity between the imperialism of Kaiser’s Germany and that of Hitler’s. Beatrice’s unfavourable view of Hanfstaengl’s personality was shared by Adolf Hitler, who had employed him in the 1920s and early 1930s as his foreign press secretary. Whereas Beatrice found Hanfstaengl’s German imperialism particularly offensive, Hitler was offended by his greedy habit of taking food off other people’s plates when eating in restaurants.

In 1916, Sarah Bernhardt, the great French actress, came for the last time to play Hamlet in New York. She had already lost a leg, and spoke Hamlet’s lines seated on a couch. Beatrice had to play all the other parts in dumb show, and was Horatio, Ophelia, Gertrude, and, for all I know, the Ghost in mute dialogue. The producer had the commercial idea of selling equally mute chorus parts to society girls from New York. In addition to responding to Bernhardt, Beatrice had to ensure that those fashionable young ladies remained in line and did not fall off the stage. She obtained a free place on one night for her beautiful younger sister, Adrienne Warren.

She remembered Sarah Bernhardt’s elocution and her professionalism. She also remembered her temperament. On one occasion, Bernhardt thought the curtain had been brought down too quickly, cutting short her applause. She turned on the stage manager and addressed him in the tones of a French Queen and the language of a French fishwife. The man operating the curtain understood the drift of her remarks, if not the precise words, and retorted by whisking up the curtain. With absolute fluency, the divine Sarah switched from her tirade to gracious acceptance of the applause of her audience. When the curtain came down, she resumed the tirade.

It was in Chicago that Beatrice first met the novelist Edna Ferber. Ferber introduced her to the Algonquin round table, and used her as copy. There is a great deal of Beatrice’s character and experience in Kim Ravenal, the youngest of the three generations of actresses in Showboat. Kim even does the elocution exercises Beatrice had taught at Wadleigh.

In 1917 a strange incident had occurred. Beatrice was at a party with some other young women of the theatre; Edna Ferber was there. One of the girls produced a Ouija board; Beatrice had a healthy Catholic distrust of the occult, had never used a Ouija board before and never touched one again. For a while the board seemed to be pointing to random letters; the young women were asking it to say whom they were going to marry. Finally the board did start to spell out recognizable words. It pointed to the letters: GOG MOG MAGOG. None of the young women knew what these words might mean, except for Edna Ferber, who said that Gog and Magog were two wooden statues of giants, to be seen at the Guildhall in London. The word ‘MOG’ remained unexplained.

On the recommendation of English actors, Beatrice decided to broaden her experience with a Shakespearian season at the Old Vic, London. She sailed for England in April 1920. There was still a post-war shortage of shipping. She booked her passage on a German liner, the old Imperator, which had been confiscated by the Allies at the end of the war. The ship had not been perfectly converted from wartime use as a troopship, and there were still German notices forbidding Other Ranks to enter the Officers’ quarters. Beatrice had to share a cabin with a young French woman who had been establishing some New York contacts for her dressmaking business. They found each other agreeable company for the voyage, and the dressmaker gave Beatrice a silk slip, which I remember seeing as a child in the 1930s. The young dressmaker was Miss Chanel.

Beatrice landed in England and went to stay with an old friend, Rosamund, who was living at Parkstone, near Bournemouth. Rosamund said she was giving a small dinner party, which would include Fletcher Rees-Mogg. She told Beatrice that Fletcher was an excellent golfer – he had a handicap of two at the Parkstone Golf Club – and a stickler for punctuality.

I have some fifty volumes of my English grandmother’s diary. It records the progress of my parents’ courtship:

10 MAY: E. F. [Edmund Fletcher Rees-Mogg] and Ed and Rosamund and Miss Warren dance. [This was either their first or second meeting.]

11 MAY: Rosamund and Miss W. (charming American) dine here. F. to works 9 to 10.30 – she and I chat, pianola.

15 MAY: F. takes Rosamund and Miss W. and me to Stonehenge. Much wind! Tea under stones!

19 MAY: v. lovely. Rosamund and B. Warren dine.

20 MAY: F. takes B. Warren to town lunch Lyndhurst, tea Sonning

26 MAY: Bea Warren comes

29 MAY: Sat 1 p.m. Fletcher and Beatrice announce their engagement.

‘Sonning’ is almost certainly a euphemism for ‘Maidenhead’. My father gave Beatrice Warren dinner on 20 May at Skindles road-house on the Thames, where he proposed. Beatrice always thought that it was slightly embarrassing to have become engaged in Maidenhead. They might well have thought that Sonning, a few miles away on the Thames, would sound less embarrassing to my grandmother’s Victorian ears. At all events, the time from their first meeting to the engagement was about a fortnight. She was twenty-eight; he was thirty.

They were to be happily married for forty-two years, and to have three children, two girls and a boy. They had, so far as I know, no fundamental disagreements. In their early letters they express surprise that such a gift of love and mutual understanding should have come to them.

They were married on 11 November 1920, by the Catholic priest, in the drawing room at Shoreacres, the Warrens’ home in Mamaroneck. They returned to England after an American honeymoon. Beatrice was not to see the United States again until after the Second World War.

Chapter Two

The Young Officer

My father was one of the young officers who survived the First World War. In the spring of 1914, he had caught pneumonia while working as a schoolmaster at a school in Lancashire, where he taught Latin, Greek and French. He was left with a strained heart. When, that August, he volunteered for the army, the doctors listened to his heart and rejected him as unfit. This, in all probability, saved his life.

Instead he went out to France by volunteering to drive the Charterhouse ambulance, which had been subscribed for by boys and parents at his old school. He was already a first-class amateur engineer and mechanic. He spent some months working at a French hospital at Arc-en-Barrois, but was subsequently commissioned in the Royal Army Service Corps, where he ran a mobile transport unit.

This was neither safe nor non-combatant. A fellow officer wrote that he woke every morning uncertain whether he would be called by his batman or St Peter. However, it was obviously less inevitably lethal than service in the infantry. It was also surprisingly modern. Apart from ambulance work, Fletcher’s unit was the first to take mobile X-rays into the front line. His experience of X-rays proved valuable when I was X-rayed in utero at the Clifton Nursing Home. The matron scrutinized the X-ray and told my parents that I had two heads. My father had seen many more X-rays than she had, and commented briskly: ‘Nonsense, woman, you don’t know how to read it.’

His unit was also attached to the earliest tanks, which, on average, broke down every 60 yards or so. Their job was to mend the tanks while under fire. My father considered that he had had an easy war. He shared the infantry’s resentment of the inadequacy of the staff officers who did not visit the front line.

Like many young officers from the landowning class – one finds the same attitudes in Anthony Eden’s memoirs – his war experience left him with a strong feeling that he ought to try to repay the privileges he had enjoyed. Some of his friends after the war were men who had been wounded, or suffered from shell shock, or had taken to drink as a result of their war experiences. For them he felt great compassion. His first cousin, Colonel Robert Rees-Mogg, a good professional soldier, had been an aide-de-camp to Field Marshal Allenby and ridden into Jerusalem in his entourage in 1917. Robert was torpedoed on his way back from Palestine, suffered from shell shock and amnesia, and never recovered. I can remember him visiting us at Cholwell, our home in Somerset, in the middle 1930s, a friendly, tall man who had lost the thread of life. Two other cousins were killed, out of a group of five, one at Gallipoli, the other in the last German advance in 1918.

I now think that I underrated the whole question of what my father had been through in the First World War. He felt, as many of those who survived did, a considerable guilt for being a survivor. The war made him feel that he should not compete in the world against people who needed the jobs. He felt that, as he had a reasonable sized estate and a reasonable income, he was in a position to lead the life of a quiet country gentleman without seeking employment and that is what he did. It was a life in which there was a lot of voluntary work and he made jobs for himself in farming which gave him an instinctive pleasure: he liked growing things; he liked having pigs; he liked having hens and he liked growing daffodils. It just about paid the wages of people who might not otherwise have had jobs during the slump.

My father inherited the long, solid, Somerset tradition of the Moggs, who had been local businessmen and landowners since at least the thirteenth century. They earned their livings as merchants, lawyers, estate agents, coal owners, bankers, clergymen, doctors, or whatever came to hand. They were involved in local government, but seem to have had little ambition to enter national politics, nor the connections to be able to do so.

In his early twenties my father inherited the family estate in Somerset, which then consisted of roughly 1200 acres and perhaps a dozen cottages, which still rented for about five shillings a week each in the 1930s and 1940s. The estate was encumbered with the death duties on his father and grandfather, and with substantial incomes payable to his sister, aunts and uncles. In capital terms he was a wealthy man, but the income that he was free to spend was not proportionate to his capital. This was the normal situation of landowners at that time, and still is today. Before the war, my father had worked briefly as a schoolmaster after spending four years at Charterhouse, four at University College, Oxford, and a further year at the Sorbonne.

By the age of twelve he had introduced me to classical Latin and Greek and even Old French. I had also been introduced to the comparative study of language. I had learned how words changed their form, so that ‘W’ in English would be the equivalent of ‘Gu’ in French, with ‘William’ matching ‘Guillaume’. I was taught the distinction between the English words which came from Germanic roots, from Norman French, from Latin and from Greek. I have never lost this interest in words. One of our own children, when little, observed that we ought to set a place for the Oxford English Dictionary at the dining table, since one or other volume was so often brought out at family lunch to look up the meaning and derivation of a particular word.

When he returned from the Sorbonne, Fletcher had had difficulty in choosing a career. His father, by then suffering from depression, had gloomy visions of Fletcher going to the bad. There had been scapegraces in the family: my great-great uncle, John Rees-Mogg, in one generation and the much-loved Charles in the next. My father was never remotely likely to become a third. Nevertheless, my grandfather, William Wooldridge Rees-Mogg, would not allow my father to become a solicitor, on the grounds that half the solicitors with whom he had trained had ended in jail for dipping into their clients’ funds. That was a pity, as my father would have made a first-class solicitor, highly intelligent, punctilious in detail, practical and exceptionally honest.

A friend of Wooldridge suggested that Fletcher might join the Chinese Consular Service, an absurd suggestion. Fletcher refused. Father and son negotiated at arm’s length, Wooldridge in the library at Cholwell, Fletcher in the morning room, passing notes to each other. One must have some sympathy with Wooldridge, who was depressed, going blind and proved to be dying. To my great benefit, Fletcher gave me the time and love which Wooldridge had not been able to give him.

Difficult father–son relationships had been common in the Mogg family, going back to the seventeenth century: they made nasty remarks about each other in their wills. My father was absolutely determined not to repeat in his relationship with me the relationship he had had with his father. And he was completely successful. On both sides our relationship was a very affectionate one of comfort and respect.

After my father was demobilized in 1919 he went to live in Parkstone, near Bournemouth. In the last months of the war he had been serving with another young officer who was in the motor business, and was a member of the Vandeleur family. Vandeleur had decided to produce a sports car for the British market. My father set up a manufacturing business to make the chassis; the engines were substantial lorry engines from the United States. Like several other ventures by young officers selling luxury cars, this looked promising for a time, but the post-war recession knocked out the market. However, my father designed the chassis and about twenty cars were constructed. In 1921, my mother’s sisters crossed the Atlantic to spend an English holiday with her. There is a picture of my American aunts and my English grandmother sitting in a Vandy, as the cars were called. It is a splendid looking car, but it does not look very economic.

In 1925 my father had the opportunity to return to Cholwell and manage his estate. He liked to grow things himself, though the farms continued to be tenanted. He kept pigs and hens and grew a large quantity of wild blackberries.

Chapter Three

A House Built on a Hill

I am standing at the top of a little hill overlooking the back of Cholwell House. No one is there except me. It is my third birthday, and is therefore 14 July 1931. I am conscious that my birthday makes me a special person in the family for that day. Much more than that, I feel that I am very much myself, am William Rees-Mogg, and that this is a good thing to be. On a good day, after a glass of champagne, I can still feel the echo of this childish triumphalism. I am certain that the William Rees-Mogg of 1931 is the same consciousness as the William Rees-Mogg I now am.

As a boy I was much surrounded by women, in a family of two elder sisters, a mother, a maiden aunt in England, two aunts in America, an American and an English grandmother, and two maiden great-aunts who lived in St James’s Square in Bath. There were also the maids and the cook, Mabel Sage. My father, myself and very distantly my clergyman great-uncle Henry Rees-Mogg were the only representatives of the male sex. I was the sole male Rees-Mogg of my generation. I did not, at the age of three or four, ask what the universe was for, what my role might be in it, or ‘what is man with regard to this infinity about him’. I knew, with the certainty of infancy, which is even more implacable than the certainty of childhood, that I was myself, that I was in my proper station. I enjoyed being me.

Many children start to ask metaphysical questions at an early age. My eldest daughter, Emma, entertained the Platonic idea of the pre-existence of souls at the age of four. The early Christian father, Origen, also held that theory, as did the English poet William Wordsworth. Emma and I were walking on the lawn at Ston Easton, when she said to me, ‘I understand what happens when we die but I don’t understand where we are before we’re born.’ Her daughter, Maud, was equally interested in questions that had interested the ancient Greek philosophers when she was four. She followed the theory, which I think was first framed by Empedocles, and since popularized by Stephen Hawking, of the plurality of worlds. ‘I know,’ she said, ‘that worlds disappear and new worlds start, but do all the other worlds have Father Christmas?’

The Elizabethan philosopher Lord Herbert of Cherbury gives a similar account of his own early development: ‘It was so long before I began to speak, that many thought I should be for ever dumb; when I came to talk, one of the furthest enquiries I made was how I came into this world? I told my nurse, keeper, and others, I found myself here indeed, but from what cause or beginning, or by what means I could not imagine, but for this I was laughed at by nurse.’

I do not remember these metaphysical problems being important to me at that age, but they have fascinated me in subsequent years. If I came into the world ‘trailing clouds of glory’, I cannot remember them.

William is a strong name; I never liked being called Bill. The association of the name with William the Conqueror helped as soon as I was reading history. I found myself a natural supporter of the Normans. I was also impressed by stories of my great-grandfather William Rees-Mogg. He was a good man of business, a local solicitor, specializing in the development of the coal industry. He built the family fortune and died a wealthy man. He had built Cholwell, where we lived. He was the dominant Victorian father figure in my family and Cholwell was his monument. The original house had been bought by the Moggs in the 1720s. It then consisted of a small Elizabethan manor house and a home farm of about a hundred acres. In 1850, William Rees-Mogg demolished the old house, which the family has subsequently regretted, and built a large Victorian country house on the hillside opposite, with a walled garden, glass houses, a conservatory and a Top and Bottom Lodge. In 1925, when my father and mother moved into Cholwell, they put in electricity and central heating. The new house was built in the Jacobean style, designed by a Bath architect who had also been responsible for the much larger Victorian pile at Westonbirt in Gloucestershire.

* * *

My first strongly political or social memory can be dated to three months after my third birthday; it relates to the General Election of 1931. The Conservative candidate is Lord Weymouth, the heir to the Marquis of Bath, supporting the National Government of Ramsay MacDonald. I am told that Lord Weymouth will be spending the day canvassing in the villages of Temple Cloud and Clutton, and that he will be bringing his daughter with him who will be left to play with me in the nursery at Cholwell.

At the age of three, I believed that all peers wore a uniform which I envisaged as being a blue velvet suit with gilt buttons. I am waiting at the front door and am disappointed when Lord Weymouth appears wearing an elegantly cut grey lounge suit with rather flared trousers, what were then called ‘Oxford bags’. He has, however, brought his daughter with him. She is of much the same age as I am. We enjoy our afternoon together, and I vaguely hope that I shall see her again. It is the first time that I am conscious of feeling the attraction of the opposite sex.

The next time I meet her it is the early 1970s and she is Lady Caroline Somerset, and we are having dinner with Arnold and Netta Weinstock in Wiltshire. At another later meeting James Lees-Milne, who thinks I am rather a prig, notes in his diary how exceptionally at ease we are together. The last time I see her she has become the Duchess of Beaufort. Like me, she has memories of having tea at Fortt’s in Bath; that is where she told her younger brother, now himself Lord Bath, that fairies do not really exist. He claims that this moment of disillusionment ruined his life.

My next political memory came in July 1934. Mabel Sage, our much-loved cook, is giving me breakfast in the dining room at Cholwell, which looks out across the terrace towards Mendip. I have eaten my boiled egg with soldiers of toast. The BBC is broadcasting a news bulletin. Hitler has just carried out his Night of the Long Knives, in which Ernst Röhm and many others are murdered. I take in this information and comment to Mabel, ‘Does this mean there will be another war?’ She replies: ‘Oh no, Hitler’s not a wicked man like the Kaiser.’

I remember the German reoccupation of the Rhineland in 1936, but only as a headline in the Daily Mail. Our family view was that it was unavoidable, that Germany was only taking back what was German territory. We did not see it as a cause for war. The Italian invasion of Abyssinia and the Spanish Civil War had more personal impact.

I do remember the shock of Mussolini’s invasion, and our sympathy with the Abyssinians. After the defeat, the Emperor of Abyssinia, Haile Selassie, went into exile in Bath, bringing members of his family with him. I was being taught to swim at the old Royal Baths in Bath by Captain Olsen, who also instructed us in climbing horizontal bars and other aspects of Swedish Drill, as physical training was then called. As I splashed around in my inflated water wings, with two princesses, Haile Selassie’s granddaughters, in the water beside me, the small but benign figure of the Lion of Judah would look down on us from the edge of the pool. He is now regarded as God by the Rastafarians. There have been many worse gods.

Spain was a matter of more passionate debate, though not inside our family. As Roman Catholics, we regarded the communists, and therefore the Spanish Republican Government, as hostile to religion; they murdered priests and raped nuns. As democrats, we disliked the Fascist Franco, but also distrusted Stalinist influence on the Republicans. We did not support either side, though I think my parents may have felt that Franco would prove to be the lesser of the two evils. From the British point of view that turned out to be correct. Franco kept Spain out of the Second World War, which a communist government might not have been able to do.

However, the young men who came to our tennis parties at Cholwell saw things differently. They correctly expected the war in Spain to be merely a prelude to the war that was coming against Hitler. I heard their arguments from afar, as an eight- or nine-year-old child listening to twenty-year-old men. I do not remember if any of our friends actually fought in Spain; some of them may have felt guilty for failing to volunteer.

In the summer of 1937, our eyes were opened to what the enemy would be like. My elder sister, Elizabeth, has a gift for languages, which she may have inherited from my father, or indeed from his mother who for some of her early years kept her diary in German, and as a young woman taught in Paris. As Elizabeth was studying German, it was proposed that she make an exchange with a German girl whose aunt had made an exchange with one of our neighbours in 1900. Jutta Lorey was to come to us; the following year, in May 1938, Elizabeth was to go to the Loreys.

We did not foresee that this would be a political question. We did not realize that the political attitudes of the Lorey family were somewhat complicated. Frau Lorey was married to a Nazi judge, who disappeared at the end of the war, thought to have been killed by the Russians. Frau Lorey’s sister Hildegarde, who, a generation earlier, had been the girl of the original exchange, was an anti-Nazi, but Frau Lorey herself kept quiet. Jutta was a member of the Bund Deutschen Madel, a fanatical sixteen-year-old Nazi child, for which she can hardly be blamed. When she made the return visit, Elizabeth spent most of her time alone or with the family’s maid, Grete. Jutta was either at college or BDM meetings, Frau Lorey was out a lot and Judge Lorey had been seconded to the east. She was aware of tensions in the family, particularly during the one weekend when the judge returned home, but these seemed more personal than political. Grete was engaged to a soldier and used to take Elizabeth to the town barracks where the soldiers were very impressed by her being English. She learned excellent German which she used later when she worked as a translator at the prisoner-of-war camp in Latimer House during the war.

Jutta’s visit to Cholwell was another matter. She brought with her all her adolescent fanaticism. She showed us her BDM dagger with its flamboyant inscription of ‘Blood and Iron’ and its swastika. She lay on her bed in the sewing room, listening on short-wave radio to Hitler’s speeches. When the door was open, I remember standing outside for a minute or two and listening to one of them. He sounded hysterical to me, a shrieking lunatic raving in a foreign tongue, but to storms of applause. I associate the crises of the 1930s with the rooms in Cholwell in which I heard different broadcasts – the dining room with the Night of the Long Knives, the sewing room with Adolf Hitler, the nursery itself with King Edward VIII’s announcement of his abdication and with Neville Chamberlain’s declaration of war on Germany.

We did not treat Jutta well. We suspected her of spying, probably rightly. The Hitler Youth who visited Britain were instructed to take photographs of local landmarks; German information packs, prepared for the 1940 invasion which never happened, included some of these snapshots. Jutta was a great photographer of landmarks. We could not stop her photographing Cholwell, which is indeed a prominent landmark, but we tried to prevent her photographing the tower of Downside Abbey. Whether we succeeded or not, I do not know.

We did not like Jutta, and she did not like us. The most spiteful thing I remember doing was cheating at Monopoly to make sure that she did not win. I have heard occasional distant accounts of her since the war, that she had been widowed, that she had become a hippy, that she was living in the Mediterranean. Among the evil things the Nazis did, the perversion of her adolescent enthusiasm is only a tiny mark. We knew, through her, that the Hitler regime was hysterical, evil and dangerous. It helped prepare us for what was to happen next.

When the war came Elizabeth joined the WAAF and worked as a translator. At the end of the war she worked on the repatriation of German prisoners of war and married a young German officer, Peter Bruegger, who had been classified as ‘White’, because he was anti-Nazi. He farmed our home farm. Though the marriage did not last, he became a popular local figure and was much loved by our children.

* * *

Until I was nine, I was educated at home. My father taught me which didn’t work terribly well when I was little because he was tall and impressive and could have a short fuse. It worked extremely well when I was a bit older. I also had lessons with Miss Farr, a young woman from Bristol, who was my sister Anne (Andy)’s excellent governess. Anne was educated at home until she was sixteen because she suffered from acute migraines. Miss Farr eventually left to marry a Mr Farr and become a Mrs Farr. If I did my lesson correctly, she would stick a coloured paper star in the exercise book; if I got five stars, she would stick in a paper duck. I was easily motivated by such rewards. Between lessons I would play with Anne in the garden. My sisters, with their long legs, climbed trees which were too difficult for me. Besides I was something of a coward and they were both bold and debonair.

In 1937, the summer of my ninth birthday, I went to board at the preparatory school of Clifton College. On the night of the Munich agreement we were supposed to be asleep in the dormitory of Matthew’s House, the Junior House, just opposite Clifton Zoo. There were twenty boys in my dormitory. We were excited by the prospect of war, not because we wanted war – we were too sensible for that – but because it would be so great an event. Mr Jones, our house tutor, was listening to the news on his radio, in the room below. Infuriatingly, we could barely hear it. However, we heard enough to know that, for the present, Munich meant peace, not war. I remember my feeling of disappointment as the adrenalin rush slowed.

I remember my own eleventh birthday on 14 July 1939, as the last carefree day of that pre-war summer. A special cake was baked at Cholwell. It had a cricket field, in green icing, two sets of stumps, a bat and a ball, all edible and made from marzipan. It was the custom at Clifton Preparatory School for the boy whose birthday it was to distribute his cake, so it had to be quite a large one, enough for thirty boys. The mood was cheerful, our exams were over, and we had prospect of the long summer holidays and I also had the August cricket festival at Weston-super-Mare to look forward to.

But only a few weeks later, on my sister Elizabeth’s birthday, 23 August, hope was extinguished by the announcement of the Nazi–Soviet pact. With Stalin as Hitler’s ally, war had become inevitable; we all knew it, in Temple Cloud just as surely as in Westminster.

On 1 September, I went down as usual to the library in Cholwell to have my morning lesson with my father. Frank Cooper, who took orders for the local grain merchant, was discussing how many bags of mixed feed my father would need for the pigs. Fletcher interrupted him to turn on the nine o’clock news on the BBC. Germany had invaded Poland. Frank Cooper left, after a few sad words. He, too, had fought in the Great War, as it was still called. My father telephoned his next contact in the network of Air Raid Precautions. He used a First World War phrase, ‘The balloon’s gone up.’

Two days later, we listened on the nursery wireless to Neville Chamberlain’s broadcast, as we had listened only less than three years before, to King Edward VIII’s abdication broadcast. Both broadcasts spoke of failure; in both there was a displeasing note of self-pity. I did not feel hostile to Neville Chamberlain, but I did not feel sorry for him either. I thought then, as I think now, that he had tried a policy of appeasement in all good faith; it had not succeeded because Hitler had always intended war. It was an honourable failure, but Neville Chamberlain’s personal disappointment was a petty thing beside the disaster which had fallen on the world. Chamberlain did not sound like a war leader.

I was still of an age when I was given supper in bed. I slept in the pink room on the south-west corner of Cholwell, with windows on one side looking down the drive and on the other looking out over Paul Wood. My supper consisted of bread and honey, a banana and a glass of milk. Later in that September, I remember listening to the evening news bulletin from my bed.

The Government was concerned that in 1914 there had been undue optimism about the length of the war, and talk of ‘the boys being home for Christmas’. They were anxious that this should not happen again, and put out an official forecast that this war would last for three years. I did not doubt that Britain would eventually win it. I assumed that the pattern of the First World War would be repeated, that eventually the United States would be drawn in, and that American industrial capacity would be decisive. I was, however, very interested in the question of how long the war would last, since I would have to plan my own life in terms of that expectation.

I remember doing a simple sum. Governments, I thought, are always wrong. If the Government thinks the war will last three years, it will be longer than that. It will probably last twice as long. I should, therefore, base my own planning on the war lasting for six years. I was now eleven years old. In six years’ time I should be seventeen. I should not be old enough to fight before the war was over.

This judgement proved to be correct – the war in Europe ended shortly before my seventeenth birthday and the war in Japan shortly thereafter. I had to do two years’ National Service, but that was in the peacetime RAF and I never regarded it as anything other than an interruption, somewhat unwelcome, in ordinary life. I do not think this attitude was unpatriotic. I was entirely prepared to join the forces. But I did decide I should concentrate on getting ahead with my school life, without thinking that I must prepare myself to be a soldier.

In fact, for the first six months, hardly anyone was doing any fighting, apart from the German invasion of Poland and the disastrous Russian invasion of Finland. At Clifton we made model aircraft out of balsa wood; the wings usually fell off mine. I remember being cold at Clifton, so cold that I used to go to bed with a torch battery in my pyjama breast pocket. I would short-circuit the battery, so that it would spread a little warmth over the area of my heart. There was also a certain amount of bullying.

One boy, in particular, was being bullied. He was a gentle, rather plump boy who came, I think, from Wales. I rather liked him. I remember discussing this with Bishop, another friend who was later killed, perhaps while still at school, in a cycling accident. I asked Bishop whether he did not think that we ought to do something about it. He gave me a political reply, based on the then unknown theory of the pecking order.

‘It would be no good,’ he said. ‘There are twelve boys in our dormitory. Each has a position in the order. “Y” – the boy who was being bullied – is twelfth. You and I are about eight and nine. We do not have the strength to intervene. If we do, we shall join “Y” in being bullied; it will do him no good and we shall then be bullied ourselves.’ I recognized the truth in Bishop’s logic and, I regret to say, accepted the realities of our political situation.

The winter passed. The spring of 1940 came and with it the German invasion of Norway, the attack on Belgium and the Netherlands, the battle for France, the fall of the Chamberlain Government, the appointment of Winston Churchill as Prime Minister. While these great events were happening, one of the boys in our house had gone down with polio; it was a mild case and he survived with little or no disability. But we were all put in quarantine, and encouraged to stay outdoors. So I heard of most of these events, and Churchill’s early speeches as Prime Minister, sitting in the bright sunshine on Clifton’s Under Green, listening to a junior master’s portable radio.

In the West Country, life went on surprisingly normally during what we all knew was an ultimate struggle for survival. There was a German daylight raid on the docks at Avonmouth. A detachment of the Coldstream Guards, having just been taken off the beaches of Dunkirk, spent a few weeks at Midsomer Norton. We felt the safer for their presence. We all followed the daily scores of German aircraft shot down in the Battle of Britain. We now know that they were exaggerated. The fear of German invasion gradually receded. Throughout this time my basic expectation did not change. I thought we would win the Battle of Britain, I believed in Winston Churchill, I did not expect an invasion to succeed, I looked to the United States as ‘the arsenal of democracy’. I felt confident that we would win in the end, as we had in 1918 and 1815.

My American aunts sent a Western Union cable in June inviting me to go to America; it even, touchingly, promised that I would be able to continue with the classics. I was rather excited by the idea, which might well have changed my life. I would, in any case, have been at greater risk from torpedoes crossing the Atlantic, than from bombs if I stayed at home. My parents took the view that they were not entitled to send me, or my sisters, if the other people of Temple Cloud could not send their children. In any case they believed in keeping the family together. I am sure that they were right, but I have always felt grateful for the invitation.

We went back to Clifton for the autumn term of 1940. A new brick and concrete shelter had been built for us at the end of Under Green; it looked like an oversized public lavatory. Thirty boys from Poole’s House slept there every night, in bunks. I did not find it disagreeable; it was certainly warmer than the dormitory.

The German night attacks on the larger cities outside London started in November. Coventry was the first to be hit. Bristol came next. We were bombed in two raids, with a week between them. On the first occasion the bombs did not come very close to our shelter, though it was a noisy night and there were large fires in the central area. My parents, in Cholwell, could see the glow of the fires, and heard the bombers passing overhead. The Heinkel bombers had a particularly penetrating, intermittent drone.

The second night was more frightening. As the sirens sounded, the matron suggested that we should all say a prayer. I suggested that we should say our normal grace, ‘For what we are about to receive, may the Lord make us truly thankful’!

The Luftwaffe used at that time to drop their bombs in sticks of four or five. In the middle of the raid, we heard a stick of bombs moving towards our shelter, which would certainly not stand a direct hit. The first bomb was loud enough, the second louder, the third louder still. The fourth was loudest of all, in fact about 50 yards away, and threw stones and earth on top of the shelter. It was apparent that the stick of bombs was falling in a straight line. If there was a fifth, it would land on top of us. We waited for it. It did not come. Although I was to be bombed again later in the war, in Somerset and London, that was the nearest I came to being killed.

After the previous night of the Bristol Blitz, my parents had thought of taking me away from Clifton. There was no question about that the second time, for them or for the school. I was driven out to Cholwell by one of the housemasters, Mr Hope Simpson, on his motorbike. We passed the burnt-out churches and the broken glass. My father had driven in but missed us on the way. The school evacuated itself to Cholwell House, sleeping on mattresses. The boys ate us out of the drums of Canadian honey which my mother, ever mindful of the Irish famine, had laid up in the cellar. After a few days most of them dispersed to their homes, and remain only as names in the Cholwell visitors’ book. My last two terms at Clifton Preparatory School were spent at Butcombe Court, a pleasant country house about ten miles from Cholwell, within bicycling distance on Sundays.

In late May 1941 I was in my last term at Clifton Preparatory School when the German battleship Bismarck sunk the Hood in the mid-Atlantic. Only three of the Hood’s crew of 1421 survived. My mother and I were taken into Temple Meads Station in Bristol by my father; we went by train to Windsor where I was about to sit the Entrance Scholarship for Eton. Most public schools were by that time sending their scholarship papers to be taken at the preparatory schools, but Eton’s only concession to the problems of wartime travel was to put up the scholarship candidates in the boys’ houses. My mother stayed at the White Lion in the High Street; I was sent to Lyttelton’s House.

The three days of the scholarship examination were interwoven with reports of the pursuit of the Bismarck by the Royal Navy. On the last evening, the Bismarck was torpedoed from the air and sank the following day. The Hood had been avenged. I found the exam papers rather too difficult for me. My Latin, thanks to my father, was tolerable, though hardly up to scholarship standards; my Greek was negligible; my French was of Common Entrance standard; my mathematics was scarcely up to that. However, I enjoyed the history paper and romped away with the essay, which was set on Satan’s fall from Heaven as described in Milton’s Paradise Lost. It was just my subject:

Him the Almighty Power

Hurled headlong flaming from th’ ethereal sky

With hideous ruin and combustion down

To bottomless perdition.

I did not need to be asked twice to describe the fires of Hell. Lyttelton later told my mother that my essay was the best of them all.

Before we went back he had a long conversation with her, which she recounted to me on the train. He did not know whether I would get the scholarship; no Eton scholarship had ever been given to a candidate as weak in the classics. In any case, he thought that I would find the atmosphere of College too tough. He said he would be very pleased to take me into his house, whether I got the scholarship or not.

We discussed this with my father when we got home. I was also entered for the Charterhouse scholarship. My father suggested that I should go to Eton if I got the Eton scholarship, go to Charterhouse if I got the Charterhouse scholarship, and go to Lyttelton’s House if I got neither. I was happy with that proposal. The Charterhouse scholarship would pay half my school fees, and I liked the idea of being a scholar. On the other hand, I much liked the atmosphere of Eton, and had been impressed by Lyttelton himself. I had even been measured for my top hat.

A few days later we received a sympathetic letter from Lyttelton saying that I had not been awarded a scholarship. Everything therefore depended on the Charterhouse exam. Fifty years later my son, Jacob, who had himself gone to Eton, heard a somewhat different story from a visiting Eton master in Hong Kong.

By this account, the 1941 examination was the last time the Provost of Eton played a part in deciding who was to receive a scholarship. The provost was Lord Quickswood, earlier Lord Hugh Cecil, son of the Lord Salisbury who was Queen Victoria’s last Prime Minister. The provost, it is said, objected on quite other grounds. He did not take his stand on the fact that I knew little Latin and less Greek, true though that was. He argued that I should not have an Eton scholarship because I was a Roman Catholic. The examiners wanted to award a scholarship; the provost prevailed; no provost was ever again invited to join in the scholarship proceedings. No Roman Catholic was ever barred again.

In the meantime, my papers were written at Butcombe Court and sent to Charterhouse. They followed the same pattern; an excellent essay, good on history, weak in Latin and French, negligible in Greek and Mathematics. Indeed, in one mathematics paper I got three marks out of a hundred. I do not know why I was so bad at elementary mathematics since in my adult life I have used them more than most people do.

Robert Birley was the Headmaster of Charterhouse. The examiners spent the Friday discussing the various papers. They found it easy to award the first scholarship, which went to Simon Raven. They awarded ten others. They came to mine, and the weight of feeling was that my classics and maths were simply not up to scholarship standard. Birley, who was himself a historian, wanted to get a potential historian into the list. On Friday evening, he was not getting his own way. If they had decided then, I would not have got the scholarship.

Robert Birley was, however, a skilled chairman of a committee. He used a device which I remember using later on a critical occasion as Chairman of the Arts Council. Because he realized that he couldn’t get the decision he wanted, he postponed it. On the following day, the examiners met again. I was nodded through for the twelfth scholarship. When the telegram arrived I was delighted.

There is no doubt that Lord Quickswood’s intervention and Birley’s persuasiveness changed my life. I know that I would have enjoyed Eton, and would have been happy in Lyttelton’s House, possibly happier than I was at Charterhouse. Indeed, I might well have been too happy, too much of an Etonian; Charterhouse presented me with greater challenges. The difference extends beyond the schools themselves, to my Oxford life, to my career. If I had gone to Eton, I doubt if I would have gone on to Balliol; I might have opted for a more sympathetic political environment at Oxford. I would probably have found my political progress easier; there were plenty of Old Etonian chairmen of safe Conservative seats in the 1950s, though few are left now.

I am grateful to Charterhouse for many things. But I felt more at home at Eton, both in 1941 and later when my son Jacob was enjoying his time there. Perhaps the real advantage of going to Charterhouse was that it did not have the same dangerous charm for someone of my interests and personality. If I had entered the world of Eton, the world of Luxmore’s garden and the College Library, of the cricket fields, of Thomas Gray and Horace Walpole, I might well have found it too much of a lifelong lotus land. Cyril Connolly, with whom I was later to work on the Sunday Times, regarded nostalgia for Eton as one of ‘The Enemies of Promise’. It was so for him, it might well have been so for me. Jacob has become a loyal Old Etonian, and Eton suited him extremely well, but he did not become addicted to its ancient charm. For myself, I think Charterhouse was probably for the best, but there were aspects of Eton, including the personality of Lyttelton himself, a remarkable and scholarly housemaster, which I would clearly have enjoyed very greatly. In the words that Senator Bill Bradley used of basketball, Charterhouse did ‘teach me to use my elbows’.

Chapter Four

A Peak in Darien

As soon as I knew how to read, I delighted in reading. I still have the copy of H. G. Wells’ Outline of History which Anne bound in a canvas jacket in 1934. It is a chunky book, of some six hundred pages. I may never have finished it, but I waded through several hundred pages. My first fascination was with the dinosaurs, but I was also interested in history as such. Before reading Wells, I had read Our Island Story, which was very imperialist, and Dickens’ Child’s History of England, which was very Protestant. I responded to his account of the Reformation by becoming equally partisan on the Catholic side. It was the Catholic martyrs I cared about; Bloody Mary became Good Queen Mary. King Henry VIII I abominated, as I still do. For Queen Elizabeth I, I had mixed feelings.

Literature forms the architecture of the mind. Shakespeare came first, even before I could read. In the winter of 1931, my mother was reading Macbeth with my sisters. We were in the nursery at Cholwell, with a fire in the little Victorian stove. I was three and a half years old, and had not yet learned how to read.

To my sisters’ irritation, my mother insisted that I should join in the reading. She would read a line, and I would repeat it after her. My sisters felt that this procedure caused undue delay, and that Lady Macbeth was too substantial a part to be given to a three-year-old; they would then have been nine and ten years old.

I can remember moments of the reading. Most vividly, I remember the scene in Macduff’s castle, when Macbeth sends his murderers to kill Lady Macduff and their son. I was young enough to identify with the son. When the murderer calls his father a traitor, the boy has the splendid line: ‘Thou ly’st, thou shag-hair’d villain’. I liked that, and I admired the courage of his last words: ‘He has kill’d me, mother; run away, I pray you’.

However, most of the lines I remember from that first reading come from my own part, that is from Lady Macbeth herself. My sisters thought it comic when I repeated the lines:

I have given suck; and know

How tender ’tis to love the babe that milks me:

I would, while it was smiling in my face,

Have pluck’d my nipple from his boneless gums,

And dash’d the brains out, had I so sworn, as you

Have done in this.

I had to ask what the words ‘I have given suck’ meant, and remember my mother explaining to me about breastfeeding, a practice I had only abandoned some three years before.

In this speech, Lady Macbeth is spurring her husband on to the murder of the old King, Duncan. Macbeth interjects ‘If we should fail’ and receives the reply:

We fail.

But screw your courage to the sticking-place,

And we’ll not fail.

This led to a discussion of Lady Macbeth’s response. How did she say ‘We fail’? Was it scornfully, as though failure was impossible, or was it fatalistically, as a consequence to be faced? In 1915 as a young actress in Margaret Anglin’s company, my mother had discussed this point with old English actors in the cast. Beatrice herself was still a junior; Margaret Anglin was playing Lady Macbeth; Tyrone Power Senior was playing Macbeth; Tyrone Power Junior was being dandled on Beatrice’s knee, as his father learned his lines. Tyrone Power Senior always found it difficult to remember his lines, but, like his son, he was a fine figure of a man, in the old Irish style.

The English actors in the cast opted for the fatalistic reading ‘We fail’, which should be said with a falling tone in a matter-of-fact way. That, they had been told by old actors of their youth, was how Sarah Siddons had pronounced it, and she was the greatest Lady Macbeth the English stage could remember. So I played the line in the Sarah Siddons tradition. My sisters were much better than I was in the role of the witches, and danced gleefully around the nursery table.

I was particularly close to my mother because when the slump came, in 1930, my parents decided that they couldn’t afford a nanny, so my mother completely took over looking after me. I was two. I spent a great deal of time with her, the two of us mostly just conversing with each other. It fell to my sisters – Elizabeth was seven years older than me and Anne six years older – to get me up and dress me which was a chore they got very bored with. I had one lovely month when my American granny, Granny Warren, came over and stayed. She was in fact dying of cancer – although she kept her illness from us all. She took over the job of dressing me in the morning and I would rush along to her bedroom and she would talk to me about her childhood in the America of the 1860s.

My mother was a hugely entertaining person to be with. She had a perfect voice, a sense of timing and a sense of occasion. She had the temperament of a star, but not of a star who made excessive claims for herself. She had wit and intelligence and energy and I remember her saying she couldn’t understand people being bored because she’d never been bored in her life.

As an actress my mother had considerable dress sense and awareness. She dressed in the smart, understated American style of the 1930s which was made fashionable in Britain by Mrs Simpson. She didn’t spend a great deal of money on her clothes. When she got married she’d been given an allowance for her clothes, by her father, in American Trading Company preference shares. But, about a year later, the American Trading Company – under a callow new proprietor – lost most of its money and stopped paying even preference dividends. My mother felt that she had had money to buy clothes in the past but that she didn’t any more. She was well dressed but thrifty.

My mother still went out on the English countryside routine of ‘making calls’. The rules still really came from the carriage days: you knew the people living in the big house of their village within a seven-mile radius and you called on them – you called on houses rather than people. Therefore you had a secondary acquaintance with people who weren’t in a seven-mile radius of your house but were in a seven-mile radius of a house on which you called. The calls were made in the afternoon and occasionally I was taken as a child with my mother to call. My mother had been fascinated by and had mastered the whole etiquette of calls and how Somerset ladies spoke to each other. She observed, as an actress, how old Lady Waldegrave used to talk. If you were visiting Lady Waldegrave, she would say, as the hostess, ‘How kind of you to come.’ And you would reply, ‘How kind of you to ask me.’ Beatrice discovered that she could play the Somerset ladies role better than the Somerset ladies themselves.

We were to read Shakespeare again as a family during the war. I remember that we read the English history plays, which seemed to have most to say about the dire circumstances of 1940 and 1941. Shakespeare always teaches the Churchillian doctrine: ‘In victory magnanimity, in defeat, defiance’. We read Richard II, which contains the great patriotic speech ‘This Sceptered Isle’ of old John of Gaunt, ‘time honoured Lancaster’. We also read King John, a much underrated play. I read the part of the Bastard, which also has a great patriotic speech, well suited to the worst days of the Second World War:

This England never did, nor never shall

Lie at the proud foot of a conqueror,

But when it first did help to wound itself.

Now these her princes are come home again,

Come the three corners of the world in arms,

And we shall shock them: Nought shall make us rue,

If England to itself do rest but true.

In 1943 and 1944, my mother took me to see John Gielgud, first in Macbeth and then in Hamlet. London was covered by the blackout, and the plays started early, so that the audiences could get home in safety. Gielgud was not, by his own high standards, a particularly memorable Macbeth; he lacked the physical characteristics for the part.

Gielgud’s Hamlet was another matter. No single actor can capture all the aspects of Hamlet’s personality. No doubt Gielgud overemphasized the intellectual and sensitive Hamlet, at the expense of the active young Prince, but his was the most moving Hamlet I have seen.

It was Shakespeare who framed my mind, in terms of my vision of the world, before my experience of adult life had set in. He gave me a sense of the drama of life, and its poetry; he gave me a sense of the variety of personality and of the range from good to evil. I was fond of the wise old men, of Cardinal Wolsey, of Polonius. Indeed, my critics might think that I have made a living out of playing Polonius on the public stage; I am particularly aware of his inability to see what a comic character he was making of himself.

I did not see Hamlet as a role model, or Julius Caesar, or any of the English kings. I knew already that I was not destined to play Romeo. It was, rather, the great speeches which gave me my picture of the world. The ancient Greeks were brought up in the same way on Homer. I do not suppose many of them thought they would grow up to be a second Achilles; it was the total effect of the poetry that gave them access to a Homeric consciousness.

In wartime, one needs to turn to great literature. Shakespeare gave that, and he also gave expression to a patriotism which makes other patriotic verse sound like a penny whistle. In peacetime, one needs to understand the world as Shakespeare sees it with affection but without illusion, with caution but without timidity, with realism as well as idealism, with humility as well as ambition, with a certain melancholy. I certainly took my politics from Shakespeare. I have never doubted that he was the leading genius of the English nation. He taught me to think, to feel, to understand and to place myself as appropriately as I might in the drama of life. Like him my politics have been rooted in the human need for order and harmony. Like him I hope for the best but fear the worst. Like him I have a Catholic nostalgia for a lost past: ‘Bare ruin’d choirs where once the sweet birds sang’.

It was in the first winter of the war, in January 1939, that I came across the next book which changed my life. I had caught a bad dose of influenza. The local doctor prescribed the new sulfa drug, M & B 693, which was later to be replaced by penicillin. I had to stay in my bedroom for two or three weeks. We still had a young housemaid, though she soon vanished, and I remember her coming in early in the morning to lay and light the bedroom fire, a luxury which lasted in English country houses down to – but seldom beyond – the outbreak of the Second World War.

As I was recovering, I wanted to find a book to read, so I went down to the Cholwell library. There I found a set of James Boswell’s Life of Johnson, which had been published by the Oxford University Press in the 1820s. I could only find the first three out of the four volumes.

I lay in bed for the next ten days, entranced and delighted by Boswell. Here the romantic lines of Keats really come close to it; Boswell’s Life of Johnson had on me the effect that Chapman’s Homer had on him:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star’d at the Pacific – and all his men

Look’d at each other with a wild surmise –

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

There were many things I found attractive about Boswell’s Life. I immediately came to share his hero-worship of Samuel Johnson:

To write the life of him who excelled all mankind in writing the lives of others, and who, whether we consider his extraordinary endorsements, or his various works, has been equalled by few in any age, is an arduous, and may be reckoned in me a presumptuous task.

I slipped easily into the notion that I was reading the life of a congenial, great man.

Johnson is also a moralist; which is a dangerous thing to be, because it is hard to make moral judgements without becoming something of a prig and a hypocrite. To Boswell, himself constantly in a state of moral torment and doubt, it was the confidence of Johnson’s morality which was most attractive. I do not think that was so in my case; no doubt I have myself been too self-confident in making moral judgements. I felt that Johnson was right to consider moral issues as essential to life. At ten I wanted to learn how to make sound moral judgements, and I wanted to know how to write good English prose. I thought Johnson could help me to learn both those things.

I respected but did not really share Johnson’s Toryism. Decades later, as I was told, Michael Hartwell, then the proprietor of the Daily Telegraph, was discussing with Bill Deedes his possible successor as Editor. I had recently given up the editor-ship of The Times, and my name was mentioned. ‘He’s not our kind of Tory,’ said Michael, and that closed the issue. I never have been a Daily Telegraph Tory, and I did not find myself a Samuel Johnson Tory either. He was a near Jacobite, King and Country, traditional Tory, although he was liberal in his views of the great social issues of race and poverty, and not an imperialist. I have always been a John Locke, Declaration of Independence, Peelite, even Pittite, type of Tory, and Johnson would have sniffed me out as a closet Whig.

It was not only Johnson’s mind and personality which attracted me, but the book itself, and above all the eighteenth century. I do not believe in reincarnation, but that is the best way to describe the impact that Boswell’s Life of Johnson had on me. I felt that I was re-entering a world to which I belonged, a world which was more real to me, and certainly more attractive, than the mid twentieth century. I felt that what had happened since Johnson’s death in 1784 was a prolonged decline of civilization, the industrial revolution, ugly architecture, the slums, the heavy Victorian age, the great European wars of Napoleon, the Kaiser and Hitler. I yearned for the age of harmony before the fall. It took me half a lifetime to get used to the modern age, and I have never become particularly fond of it.

In reading Boswell, I was able to slip into the garden of the eighteenth century and regain a lost paradise. I enjoyed everything about that century, the houses, the furniture, the landscape, the paintings, the music, the literature, the letters, the politics, the people. Although this perception of the eighteenth century as a golden age has gradually eroded, it still remains quite vivid. In the years when our own family was growing up, Gillian and I lived in two fine eighteenth-century houses, Ston Easton Park in Somerset – a beautiful extravagance – and Smith Square in London. Now we live in an early twentieth-century flat in London and a late fifteenth-century house in Somerset. I delight in both of them; the eighteenth-century nostalgia has eased. But it is still the period from 1714, the death of Queen Anne, to 1789, the year of the French Revolution, which is my true homeland in history and literature.

I never suffered from Johnson’s extreme fear of death, but I did feel sympathetic to his congenital melancholy. I also admired the energy he put into friendship. The passage I best remember from my first reading of Boswell’s Life is the one in which he helped a nearly destitute Oliver Goldsmith; this account is in Johnson’s own words:

I received one morning a message from poor Goldsmith, that he was in great distress, and as it was not in his power to come to me, begging that I would come to him as soon as possible. I sent him a guinea, and promised to come to him directly. I accordingly went as soon as I was dressed, and found that his landlady had arrested him for his rent, at which he was in a violent passion. I perceived that he had already changed my guinea, and had got a bottle of Madeira and a glass before him. I put the cork into the bottle, desired he would be calm, and began to talk to him of the means by which he might be extricated. He then told me that he had a novel ready for the press, which he produced to me. I looked into it, and saw its merit, told the landlady I should soon return, and having gone to a bookseller, sold it for sixty pounds. I brought Goldsmith the money, and he discharged his rent, not without rating his landlady in a high tone for having used him so ill.

The novel was The Vicar of Wakefield; £60 would probably have had the purchasing power of £5000 in modern money.

That summer I was in the senior form of the junior section of the Clifton Preparatory School, a form taught by Captain Read. With war imminent, it was a time of heightened emotional tension, a time when everyone’s imagination was stretched. Read was a quiet man, a good schoolmaster, who was a veteran of the First World War. I now suspect that he may have been one of those good officers who never wholly recovered from their war experience; he did not speak of it to us.